Computational Modeling of Multiple-Phase Transformations in API X70 and X80 Steels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Dilatometry

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4. Electron Back-Scattered Diffraction

2.5. Microstructure Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Analysis of X70 and X80

3.2. Phase Quantification of X70 and X80

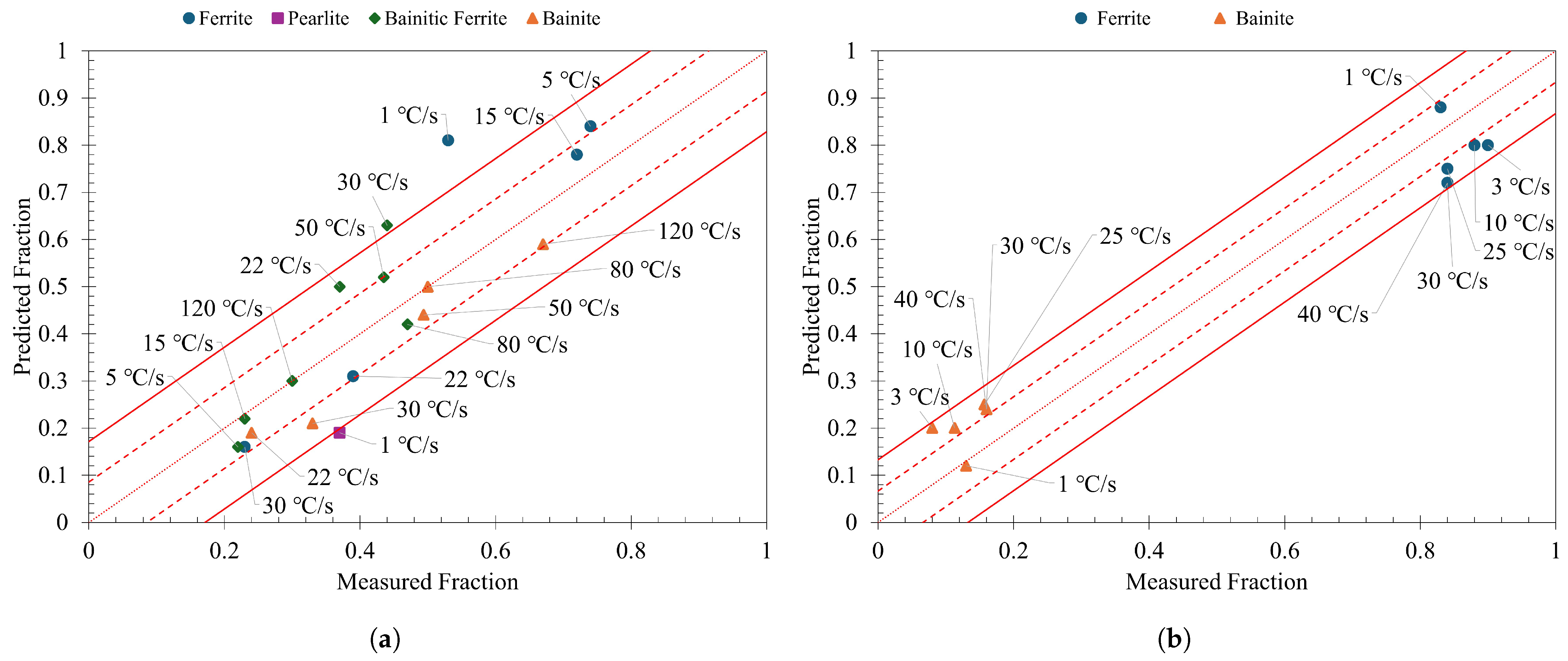

3.3. Model Predictions

3.4. Continuous Cooling Transformation Diagrams

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B | Bainite |

| BM | Bainite-martensite |

| BF | Bainitic ferrite |

| DP | Degenerate pearlite |

| F | Ferrite |

| MA | Marteniste-austenite |

| P | Pearlite |

| PF | Polygonal ferrite |

| QPF | Quasi-polygonal ferrite |

| WF | Widmanstätten ferrite |

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| CR | Cooling rate | °C/s |

| Dilation length | µm | |

| Dilation tangent of phase i | µm | |

| Fraction of phase i | - | |

| K, L | Linear phase fraction constants | - |

| Martensite start temperature | °C | |

| Q | Activation energy | J/mol |

| R | Gas constant | J/(mol.K) |

| t | Time | s |

| T | Temperature | °C |

| V | Volume | |

| Fraction of phase i | - | |

| Time parameter | s | |

| Pre-exponential factor | s |

References

- Gray, J.M. Technology of microalloyed steel for large diameter pipe. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 1974, 2, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D. Microalloyed steels for the automotive industry. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. E Mineraç Ao 2014, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Chen, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Liu, W.; Wu, H.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. The Effects of Microalloying on the Precipitation Behavior and Strength Mechanisms of X80 High-Strength Pipeline Steel under Different Processes. Crystals 2023, 13, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.F.M.M.; Ehrhardt, B.; Kumar, N. Studying the Microstructural Evolution in a Hot-Rolled Thick Gauge Microalloyed Line Pipe Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 12984–13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Gao, B.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, R.; Gui, H.; Chu, Z. High-Strength Low-Alloy Steels for Automobiles: Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenaglia, N.E.; Speer, J.G.; Hernandez Duran, E.; De Moor, E. Effects of Mn and Nb Alloying on Austenite Decomposition in High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) Steels for Long Structural Applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2025, 56, 2820–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kop, T.A.; Sietsma, J.; Van Der Zwaag, S. Dilatometric analysis of phase transformations in hypo-eutectoid steels. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, I.; Sekine, H.; Tanaka, T. Thermomechanical Processing of High-Strength Low-Alloy Steels; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulok, R.; Kawulok, P.; Schindler, I.; Opěla, P.; Rusz, S.; Ševčák, V.; Solowski, Z. Study of the effect of deformation on transformation diagrams of two low-alloy manganese-chromium steels. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2018, 63, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.b.; Sun, X.j.; Liu, Q.y.; Zhang, Z.b. Influence of deformation on transformation of low-carbon and high Nb-containing steel during continuous cooling. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2010, 17, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawulok, R.; Schindler, I.; Sojka, J.; Kawulok, P.; Opěla, P.; Pindor, L.; Grycz, E.; Rusz, S.; Ševčák, V. Effect of strain on transformation diagrams of 100Cr6 steel. Crystals 2020, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prislupčák, P.; Kvačkaj, T.; Bidulská, J.; Záhumenský, P.; Homolová, V.; Zimovčák, P. Austenite—Ferrite Transformation Temperatures of C Mn Al HSLA Steel. Acta Metall. Slovaca 2021, 27, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, M.; Krasnov, M.; Urtsev, V.; Danilov, S.; Pastukhov, V. Effect of cooling rate on the structure of low-carbon low-alloy steel after thermomechanical controlled processing. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2019, 61, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, M. 2.1 Fundamentals of heat treating metals and alloys. In Comprehensive Materials Finishing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.; Bhadeshia, H. Kinetics of the simultaneous decomposition of austenite into several transformation products. Acta Mater. 1997, 45, 2911–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, M.; Mohanty, O.; Ghosh, R. Modelling of transformation kinetics in HSLA 100 steel during continuous cooling. Scand. J. Metall. 2001, 30, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Girault, E.; Jacques, P.; Harlet, P.; Mols, K.; Van Humbeeck, J.; Aernoudt, E.; Delannay, F. Metallographic methods for revealing the multiphase microstructure of TRIP-assisted steels. Mater. Charact. 1998, 40, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wray, P.J.; Garcia, C.I.; Hua, M.; DeArdo, A.J. Image quality analysis: A new method of characterizing microstructures. ISIJ Int. 2005, 45, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, D. Extension of the martensite transformation temperature relation to larger alloying elements and contents. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Van Tyne, C.J. A kinetics model for martensite transformation in plain carbon and low-alloyed steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2012, 43, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- van Bohemen, S.M.; Sietsma, J. Modeling of isothermal bainite formation based on the nucleation kinetics. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 99, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.M.; Sietsma, J.; Santofimia, M.J. Exploring bainite formation kinetics distinguishing grain-boundary and autocatalytic nucleation in high and low-Si steels. Acta Mater. 2016, 105, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, G.; Thompson, S.W. Ferritic microstructures in continuously cooled low-and ultralow-carbon steels. ISIJ Int. 1995, 35, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.A.; Easterling, K.E.; Sherif, M.Y. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H.; Christian, J. Bainite in steels. Metall. Trans. A 1990, 21, 767–797. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Bhadeshia, H.; Lee, H.C. Effect of plastic deformation on the formation of acicular ferrite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 360, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, F. 12—Carbide-free bainite in steels. In Phase Transformations in Steels; Pereloma, E., Edmonds, D.V., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 436–467. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, R.; Hansen, S. Effects of austenite grain size and cooling rate on Widmanstätten ferrite formation in low-alloy steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1994, 25, 665–675. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y.; Li, D.; Li, Y. Modeling austenite decomposition into ferrite at different cooling rate in low-carbon steel with cellular automaton method. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Colvin, D.; Krauss, G. Austenite decomposition during continuous cooling of an HSLA-80 plate steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1996, 27, 1557–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, D.; Asl, S.K.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Daneshi, G. Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and mechanical properties of microalloyed forging steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 206, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, M.; Li, D.; Li, Y. Modeling the austenite–ferrite diffusive transformation during continuous cooling on a mesoscale using Monte Carlo method. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sui, G.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D. Phase transformation mechanism of low-carbon high strength low alloy steel upon continuous cooling. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S8-416–S8-422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Bainite in Steels: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. 10—Mechanisms of bainite transformation in steels. In Phase Transformations in Steels; Pereloma, E., Edmonds, D.V., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 385–416. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Liu, C.; Yan, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, Y. Formation mechanism and control methods of acicular ferrite in HSLA steels: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | C | Mn | Cr + Ni + Mo + Cu | Nb | Ti | Si | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X70 | 0.05 | 1.52 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.014 | 0.24 | 0 |

| X80 | 0.06 | 1.69 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 0.0003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karl, R.; Valloton, J.; Cathcart, C.; Zhou, T.; Fazeli, F.; Wiskel, J.B.; Henein, H. Computational Modeling of Multiple-Phase Transformations in API X70 and X80 Steels. Metals 2025, 15, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121379

Karl R, Valloton J, Cathcart C, Zhou T, Fazeli F, Wiskel JB, Henein H. Computational Modeling of Multiple-Phase Transformations in API X70 and X80 Steels. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121379

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarl, Ry, Jonas Valloton, Chad Cathcart, Tihe Zhou, Fateh Fazeli, J. Barry Wiskel, and Hani Henein. 2025. "Computational Modeling of Multiple-Phase Transformations in API X70 and X80 Steels" Metals 15, no. 12: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121379

APA StyleKarl, R., Valloton, J., Cathcart, C., Zhou, T., Fazeli, F., Wiskel, J. B., & Henein, H. (2025). Computational Modeling of Multiple-Phase Transformations in API X70 and X80 Steels. Metals, 15(12), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121379