Selection of Processing Parameters in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for the Production of Iron Cellular Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Experiments (DoE) and Process Optimization

2.2. Characterization of Iron Samples

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Feedstock Iron Particles

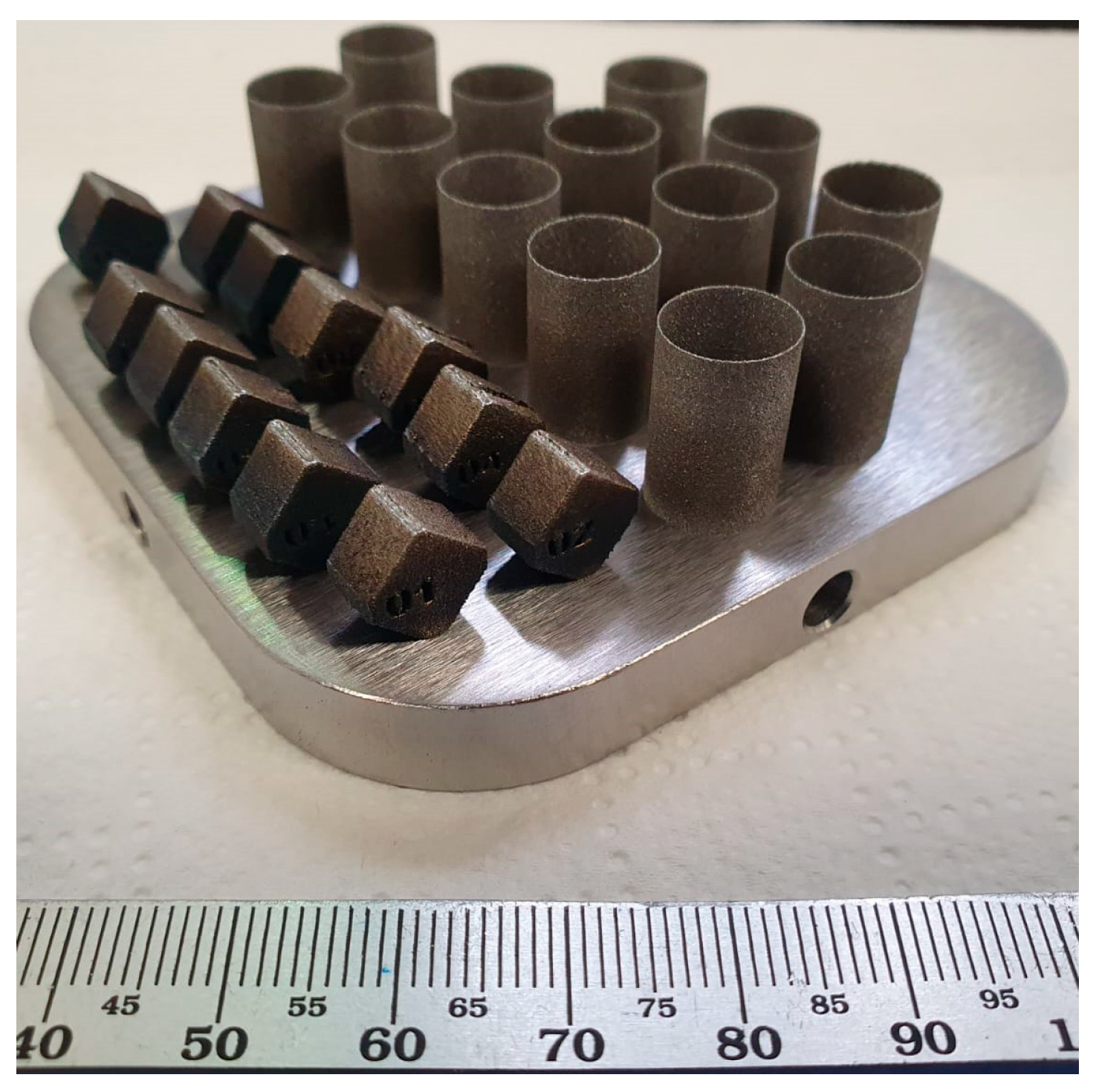

3.2. PBF-LB Process Optimization

| Sample | Hatch Laser Power (W) | Hatch Distance (μm) | Point Distance (µm) | Scanning Speed (mm/s) | VED (J/mm3) | Mass (g) | Archimedes Density (%) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 160 | 110 | 24 | 1200 | 40.4 | 4.075 | 79.50% | - |

| 2 | 160 | 90 | 12 | 600 | 98.8 | 4.716 | 92.00% | - |

| 3 | 180 | 100 | 24 | 1200 | 50.0 | 4.356 | 84.98% | - |

| 4 | 140 | 100 | 12 | 600 | 77.8 | 4.210 | 82.12% | 0.25% |

| 5 | 180 | 110 | 18 | 900 | 60.6 | 4.139 | 80.75% | - |

| 6 | 140 | 90 | 18 | 900 | 57.6 | 4.091 | 79.80% | - |

| 7 | 180 | 90 | 24 | 1200 | 55.6 | 4.083 | 79.66% | - |

| 8 | 140 | 110 | 12 | 600 | 70.7 | 3.969 | 77.42% | - |

| 9 | 180 | 90 | 12 | 600 | 111.1 | 4.724 | 92.16% | 0.14% |

| 10 | 140 | 110 | 24 | 1200 | 35.4 | 3.758 | 73.30% | 7.59% |

| 11 | 180 | 110 | 12 | 600 | 90.9 | 4.812 | 93.87% | 0.07% |

| 12 | 140 | 90 | 24 | 1200 | 43.2 | 3.899 | 76.06% | - |

| 13 | 160 | 100 | 18 | 900 | 59.3 | 4.371 | 85.28% | - |

3.3. Design of Experiments

3.3.1. Border

| Sample | Border Laser Power (W) | Border Point Distance (μm) | Additional Border Power (W) | Additional Border Point Distance (μm) | Hatch Offset (μm) | Border Distance (μm) | SED (J/mm2) | Optical Porosity (%) | Optical Border Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 180 | 12 | 180 | 12 | −50 | 70 | 10 | 0.074 ± 0.037 | 0.530 ± 0.654 |

| 2 | 180 | 4 | 240 | 12 | −10 | 50 | 30 | 0.182 ± 0.138 | 0.104 ± 0.107 |

| 3 | 240 | 4 | 180 | 4 | −50 | 50 | 40 | 0.079 ± 0.059 | 0.668 ± 0.296 |

| 4 | 300 | 12 | 180 | 8 | −10 | 50 | 17 | 0.123 ± 0.224 | 0.113 ± 0.181 |

| 5 | 300 | 12 | 240 | 4 | −50 | 90 | 17 | 0.033 ± 0.037 | 0.024 ± 0.041 |

| 6 | 240 | 8 | 240 | 8 | −30 | 70 | 20 | 0.072 ± 0.087 | 0.264 ± 0.379 |

| 7 | 180 | 4 | 300 | 8 | −50 | 90 | 30 | 0.745 ± 0.185 | 1.853 ± 1.039 |

| 8 | 240 | 12 | 300 | 12 | −10 | 90 | 13 | 0.042 ± 0.030 | 0.003 ± 0.005 |

| 9 | 180 | 8 | 180 | 4 | −10 | 90 | 15 | 0.179 ± 0.146 | 0.309 ± 0.202 |

| 10 | 300 | 4 | 300 | 4 | −10 | 70 | 50 | 0.200 ± 0.271 | 0.147 ± 0.209 |

| 11 | 300 | 8 | 300 | 12 | −50 | 50 | 25 | Not possible to manufacture | |

| 12 | 180 | 12 | 300 | 4 | −30 | 50 | 10 | 0.337 ± 0.482 | 0.063 ± 0.054 |

| 13 | 300 | 4 | 180 | 12 | −30 | 90 | 50 | 0.160 ± 0.062 | 0.071 ± 0.106 |

3.3.2. Thin Wall

| Sample | Block Path Hatch Laser Power (W) | Block Path Point Distance (μm) | Block Path Scanning Speed (mm/s) | LED (J/mm) | Thickness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (μm) | Standard Deviation (μm) | Error (%) | |||||

| 1 | 160 | 24 | 1200 | 0.133 | 133.1 | 9.4 | −16.8 |

| 2 | 160 | 12 | 0600 | 0.267 | 109.7 | 20.8 | −31.4 |

| 3 | 180 | 24 | 1200 | 0.150 | 109.9 | 18.1 | −31.3 |

| 4 | 140 | 12 | 600 | 0.233 | 122.8 | 19.4 | −23.3 |

| 5 | 180 | 18 | 900 | 0.200 | 124.8 | 14.3 | −22.0 |

| 6 | 140 | 18 | 900 | 0.156 | 102.8 | 20.1 | −35.8 |

| 7 | 180 | 12 | 600 | 0.300 | 145.3 | 12.9 | −9.2 |

| 8 | 140 | 24 | 1200 | 0.117 | 90.0 | 30.1 | −43.8 |

| 9 | 160 | 18 | 900 | 0.178 | 111.7 | 14.0 | −30.2 |

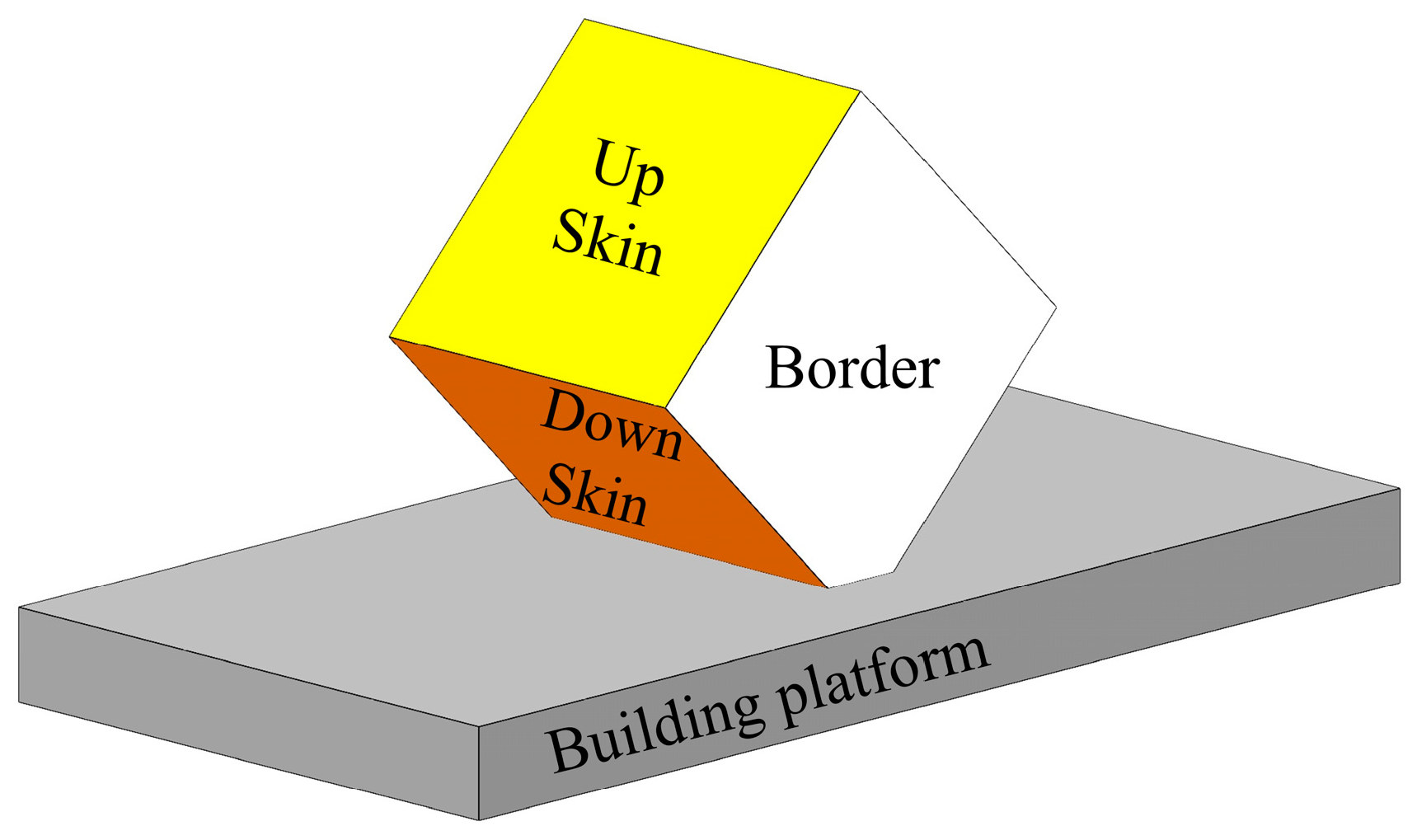

3.3.3. Skin

| Sample | Hatch Laser Power (W) | Hatch Distance (μm) | Hatch Offset (μm) | Point Distance (µm) | Scanning Speed (m/s) | Relative Density (%) | Border Roughness (Ra) (µm) | Downskin Surface Roughness (Ra) (µm) | Upskin Surface Roughness (Ra) (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 160 | 100 | −30 | 18 | 0.9 | 98.73% | 9.821 | 31.217 | 10.968 |

| 2 | 140 | 110 | −30 | 12 | 0.6 | 98.94% | 13.216 | 37.387 | 13.240 |

| 3 | 140 | 90 | −10 | 24 | 1.2 | 98.58% | 11.674 | 28.756 | 16.454 |

| 4 | 180 | 90 | −10 | 12 | 0.6 | 98.77% | 11.836 | 38.142 | 14.165 |

| 5 | 160 | 110 | −10 | 24 | 1.2 | 98.97% | 12.939 | 33.321 | 12.301 |

| 6 | 180 | 90 | −30 | 24 | 1.2 | 99.09% | 10.506 | 31.104 | 14.860 |

| 7 | 140 | 100 | −10 | 12 | 0.6 | 98.96% | 11.621 | 35.923 | 15.910 |

| 8 | 180 | 100 | −50 | 24 | 1.2 | 98.47% | 11.751 | 29.348 | 18.374 |

| 9 | 140 | 110 | −50 | 24 | 1.2 | 99.22% | 10.236 | 29.772 | 14.701 |

| 10 | 140 | 90 | −50 | 18 | 0.9 | 98.55% | 11.523 | 27.194 | 14.109 |

| 11 | 160 | 90 | −50 | 12 | 0.6 | 99.25% | 11.964 | 22.363 | 13.249 |

| 12 | 180 | 110 | −10 | 18 | 0.9 | 99.34% | 12.268 | 35.770 | 10.184 |

| 13 | 180 | 110 | −50 | 12 | 0.6 | 98.66% | 12.448 | 26.795 | 14.283 |

3.3.4. Beam Compensation

3.4. Lattice Geometries

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimharaju, S.R.; Zeng, W.; See, T.L.; Zhu, Z.; Scott, P.; Jiang, X.; Lou, S. A comprehensive review on laser powder bed fusion of steels: Processing, microstructure, defects and control methods, mechanical properties, current challenges and future trends. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 75, 375–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Yadaiah, N.; Prakash, C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Dixit, S.; Gupta, L.R.; Buddhi, D. Laser powder bed fusion: A state-of-the-art review of the technology, materials, properties & defects, and numerical modelling. J. Mater. Technol. 2022, 20, 2109–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobel, A.; Anam, M.d.A.; Lorenzo-Martin, C.; Gould, B.; Hector, L.G.; Greco, A. Additive manufacturing process parameter determination for a new Fe-C-Cu alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 101, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassoli, E.; Sola, A.; Celesti, M.; Calcagnile, S.; Cavallini, C. Development of Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion Process Parameters and Scanning Strategy for New Metal Alloy Grades: A Holistic Method Formulation. Materials 2018, 11, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, S.; Shi, S.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Ward, R.M. Effect of processing parameters on surface roughness, porosity and cracking of as-built IN738LC parts fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 285, 116788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, J.; Koch, R.; Kaiser, D.; Graf, G.; Dietrich, S.; Schulze, V. Process development and impact of intrinsic heat treatment on the mechanical performance of selective laser melted AISI 4140. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Q. Optimization of surface roughness and dimensional accuracy in LPBF additive manufacturing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 142, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.; Magrinho, J.P.G.; Silva, M.B.; Moita de Deus, A.; Vaz, M.F. Compression properties of cellular iron lattice structures used to mimic bone characteristics. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2024, 238, 2217–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhmalev, P.; Fredriksson, G.; Svensson, K.; Yadroitsev, I.; Yadroitsava, I.; Thuvander, M.; Peng, R. Microstructure, Solidification Texture, and Thermal Stability of 316 L Stainless Steel Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2018, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayazfar, H.; Salarian, M.; Rogalsky, A.; Sarker, D.; Russo, P.; Paserin, V.; Toyserkani, E. A critical review of powder-based additive manufacturing of ferrous alloys: Process parameters, microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2018, 144, 98–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Hariharan, A.; Kini, A.; Kürnsteiner, P.; Raabe, D.; Jägle, E.A. Steels in additive manufacturing: A review of their microstructure and properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Ding, J.; Song, X. Achieving triply periodic minimal surface thin-walled structures by micro laser powder bed fusion process. Micromachines 2021, 12, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, G.; Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. Understanding the effect of scanning strategies on the microstructure and crystallographic texture of Ti-6Al-4V alloy manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 299, 117366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rometsch, P.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, A. Review of high-strength aluminium alloys for additive manufacturing by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Feng, B.; Yang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, Q.; Cui, L.; Tong, X.; Hao, S. Effect of laser scanning speed on the microstructure, phase transformation and mechanical property of NiTi alloys fabricated by LPBF. Mater. Des. 2022, 215, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Hor, A.; Copin, E.; Lours, P.; Ratsifandrihana, L. Correlation between microstructure heterogeneity and multi-scale mechanical behavior of hybrid LPBF-DED Inconel 625. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 303, 117542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Sasahara, H.; Abe, T.; Sannomiya, H.; Nishiyama, S.; Ohta, S.; Nakamura, K. Material-property evaluation of magnesium alloys fabricated using wire-and-arc-based additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pavanram, P.; Zhou, J.; Lietaert, K.; Taheri, P.; Li, W.; San, H.; Leeflang, M.A.; Mol, J.M.C.; Jahr, H.; et al. Additively manufactured biodegradable porous zinc. Acta Biomater. 2020, 101, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Dong, S.; Deng, S.; Liao, H.; Coddet, C. Microstructure and tensile properties of iron parts fabricated by selective laser melting. Opt. Laser Technol. 2014, 56, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.P.; Froyen, L.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; Mercelis, P.; Rombouts, M.; Lauwers, B. Selective laser melting of iron-based powder. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 149, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, T.; Gurung, K.; Meyers, S.; Cutolo, A.; Oh, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Van Hooreweder, B.; Lee, C.S. A new strategy for metal additive manufacturing using an economical water-atomized iron powder for laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 308, 117705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeeh, V.P.M.; Hanas, T. Biodegradable Iron Implants: Development, Processing, and Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Vaz, M.F.; Colaço, R.; Santos, C.; Carmezim, M. Biodegradable iron and porous iron: Mechanical properties, degradation behaviour, manufacturing routes and biomedical applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Shangguan, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, A. A metamaterial bone plate for biofixation based on 3D printing technology. Int. J. Bioprinting 2024, 10, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, K.; Han, W.; Wu, Y.; Chang, H.; Kong, L. Design and biomechanical evaluation of laser powder bed fusion manufactured Ti6Al4V fusion cages with tunable lattice-induced stress distribution. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wu, Y.; Huang, L.; Pan, C.; Sun, Y.; Tian, S.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y. Scanning strategies for the 316L part with lattice structures fabricated by selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 3165–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Liang, S.-X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.C. Additive manufacturing of metallic lattice structures: Unconstrained design, accurate fabrication, fascinated performances, and challenges. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 146, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, F.; Mineo, R.; Epasto, G. Mechanical behaviour of a novel biomimetic lattice structure for bone scaffold. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 138, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, F.; Noelke, C.; Kaierle, S.; Haferkamp, H.; Gesing, T.M. Influence of Foaming Agents on Laser Based Manufacturing of Closed-cell Ti Foam. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 4, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jahr, H.; Lietaert, K.; Pavanram, P.; Yilmaz, A.; Fockaert, L.I.; Leeflang, M.A.; Pouran, B.; Gonzalez-Garcia, Y.; Weinans, H.; et al. Additively manufactured biodegradable porous iron. Acta Biomater. 2018, 77, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadpoor, A.A. Additively manufactured porous metallic biomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 4088–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, D.; Xu, C.; Venezuela, J.; Cao, Y.; Kent, D.; Bermingham, M.; Demir, A.G.; Previtali, B.; Ye, Q.; Dargusch, M. Additively manufactured iron-manganese for biodegradable porous load-bearing bone scaffold applications. Acta Biomater. 2020, 103, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASM Handbook Committee. Volume 1: Properties and Selection: Irons, Steels, and High-Performance Alloys; American Society for Metals, ASM International: Russell Township, OH, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, E.W.; Pegues, J.; Moore, D.; Saldaña, C. Process-Structure-Property Relationships of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Lattice Structures. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 091007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lifton, J.; Hu, Z.; Hong, R.; Feih, S. Influence of geometric defects on the compression behaviour of thin shell lattices fabricated by micro laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.; Lopes, P.; Oliveira, L.; Alves, J.L.; Magrinho, J.P.G.; Deus, A.M.; De Vaz, M.F.; Silva, M.B. Evaluation of Lattice Structures for Medical Implants: A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Various Unit Cell Types. Metals 2024, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.; Silva, M.B.; Moita de Deus, A.; Cláudio, R.; Carmezim, M.; Santos, C.; Magrinho, J.; Reis, L.; Lino, J.; Oliveira, L.; et al. Evaluation of the roughness of lattice structures of AISI 316 stainless steel produced by laser powder bed fusion. Eng. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukkum, V.B.; Sanborn, T.; Shepherd, J.; Saptarshi, S.; Basu, R.; Horn, T.; Gupta, R.K. Influence of Spatter on Porosity, Microstructure, and Corrosion of Additively Manufactured Stainless Steel Printed Using Different Island Size. Crystals 2024, 14, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, W.H.; Chiu, L.N.S.; Lim, C.V.S.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, D.; Huang, A. A critical review on the effects of process-induced porosity on the mechanical properties of alloys fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 9818–9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.C.; Thole, K.A. Understanding Laser Powder Bed Fusion Surface Roughness. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 071003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Garmestani, H.; Liang, S.Y. Prediction of Upper Surface Roughness in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, T.; Kim, J.-Y.; Gurung, K.; Meyers, S.; Van Hooreweder, B.; Lee, J.-S.; Kim, J.-K.; Lee, C.S. Impact of laser scanning strategies on microstructure in laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) of nanoparticle-infused pre-alloyed water-atomized iron powder. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 891, 145989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, K. Osteogenesis of 3D printed porous Ti6Al4V implants with different pore sizes. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomeu, F.; Costa, M.M.; Alves, N.; Miranda, G.; Silva, F.S. Selective Laser Melting of Ti6Al4V sub-millimetric cellular structures: Prediction of dimensional deviations and mechanical performance. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 113, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (J kg−1 K−1) | (K) | (J kg−1) | (kg mm−3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 440 | 1510 | 272,000 | 7.87 × 10−6 | 0.455 | 0.090 | 0.2 |

| Sample | Beam Compensation (µm) | Theoretical Relative Density (%) | Relative Density (%) | Relative Density Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 10.28 | 23.5 | 128.6 |

| 2 | 90 | 10.28 | 14.6 | 42.0 |

| 3 | 100 | 10.28 | 13.2 | 28.4 |

| 4 | 110 | 10.28 | 12.6 | 22.6 |

| 5 | 120 | 10.28 | 11.1 | 8.0 |

| 6 | 130 | 10.28 | 10.1 | −1.8 |

| 7 | 135 | 10.28 | 9.7 | −5.6 |

| 8 | 150 | 10.28 | 7.1 | −30.9 |

| Hatch Laser Power (W) | Hatch Distance (μm) | Point Distance (µm) | Scanning Speed (m/s) | VED (J/mm3) | ||

| 180 | 110 | 12 | 0.6 | 90.9 | ||

| Volume Border Laser Power (W) | Volume Border Point Distance (μm) | Additional Border Laser Power (W) | Additional Border Point Distance (μm) | Hatch Offset (μm) | Border Distance (mm) | SED (J/mm2) |

| 240 | 12 | 300 | 12 | −10 | 0.09 | 13 |

| Downskin Hatch Laser Power (W) | Downskin Hatch Distance (μm) | Downskin Hatch Offset (μm) | Downskin Point Distance (µm) | Downskin Scanning Speed (m/s) | ||

| 160 | 90 | −50 | 12 | 0.6 | ||

| Upskin Hatch Laser Power (W) | Upskin Hatch Distance (μm) | Upskin Hatch Offset (μm) | Upskin Point Distance (µm) | Upskin Scanning Speed (m/s) | ||

| 180 | 110 | −10 | 18 | 0.9 | ||

| Block Path Hatch Laser Power (W) | Block Path Point Distance (µm) | Block Path Scanning Speed (m/s) | LED (J/mm3) | |||

| 180 | 12 | 0.6 | 0.300 | |||

| Beam Compensation (µm) | Hatch Compensation | |||||

| 130 | No | |||||

| Sample | Theoretical Relative Density (%) | Relative Density (%) | Relative Density Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTCO—low density | 10.28 | 10.98 | 6.81 |

| RTCO—medium density | 35.29 | 35.34 | 0.14 |

| RTCO—high density | 65.16 | 67.27 | 3.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogueira, P.; Magrinho, J.P.G.; Batalha, R.L.; Rosa, M.J.; Cabral, A.; Morais, P.; Reis, L.; Santos, C.; Carmezim, M.J.; Cláudio, R.; et al. Selection of Processing Parameters in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for the Production of Iron Cellular Structures. Metals 2025, 15, 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121355

Nogueira P, Magrinho JPG, Batalha RL, Rosa MJ, Cabral A, Morais P, Reis L, Santos C, Carmezim MJ, Cláudio R, et al. Selection of Processing Parameters in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for the Production of Iron Cellular Structures. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121355

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogueira, Pedro, João P. G. Magrinho, Rodolfo L. Batalha, Maria J. Rosa, Ana Cabral, Paulo Morais, Luis Reis, Catarina Santos, Maria J. Carmezim, Ricardo Cláudio, and et al. 2025. "Selection of Processing Parameters in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for the Production of Iron Cellular Structures" Metals 15, no. 12: 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121355

APA StyleNogueira, P., Magrinho, J. P. G., Batalha, R. L., Rosa, M. J., Cabral, A., Morais, P., Reis, L., Santos, C., Carmezim, M. J., Cláudio, R., Deus, A. M. d., Silva, M. B., & Vaz, M. F. (2025). Selection of Processing Parameters in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for the Production of Iron Cellular Structures. Metals, 15(12), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121355