Production and Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V Foams Produced by the Replica Impregnation Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

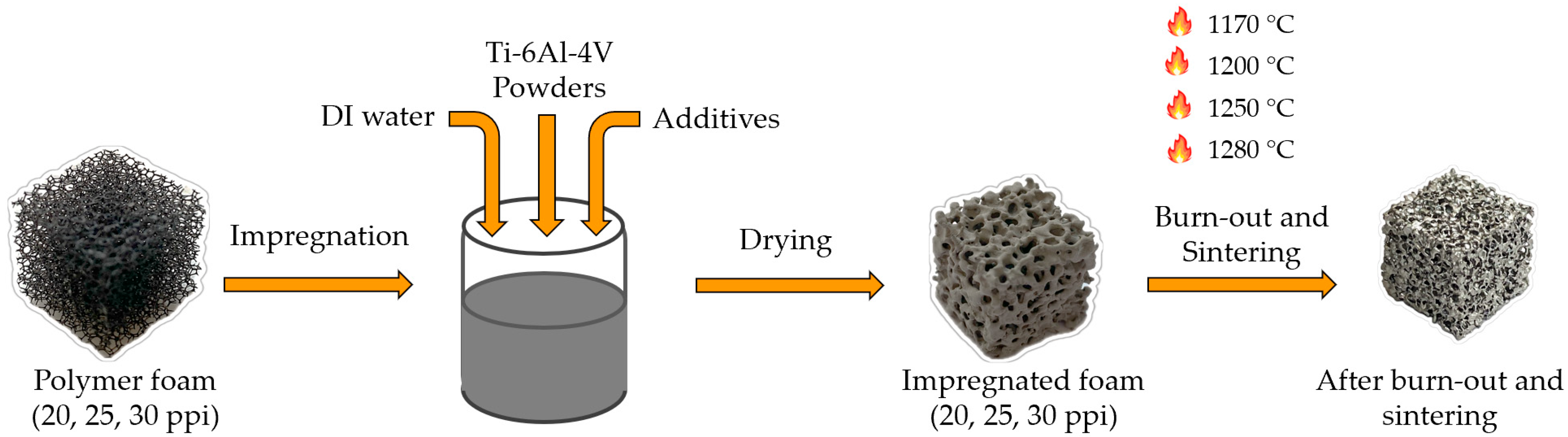

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

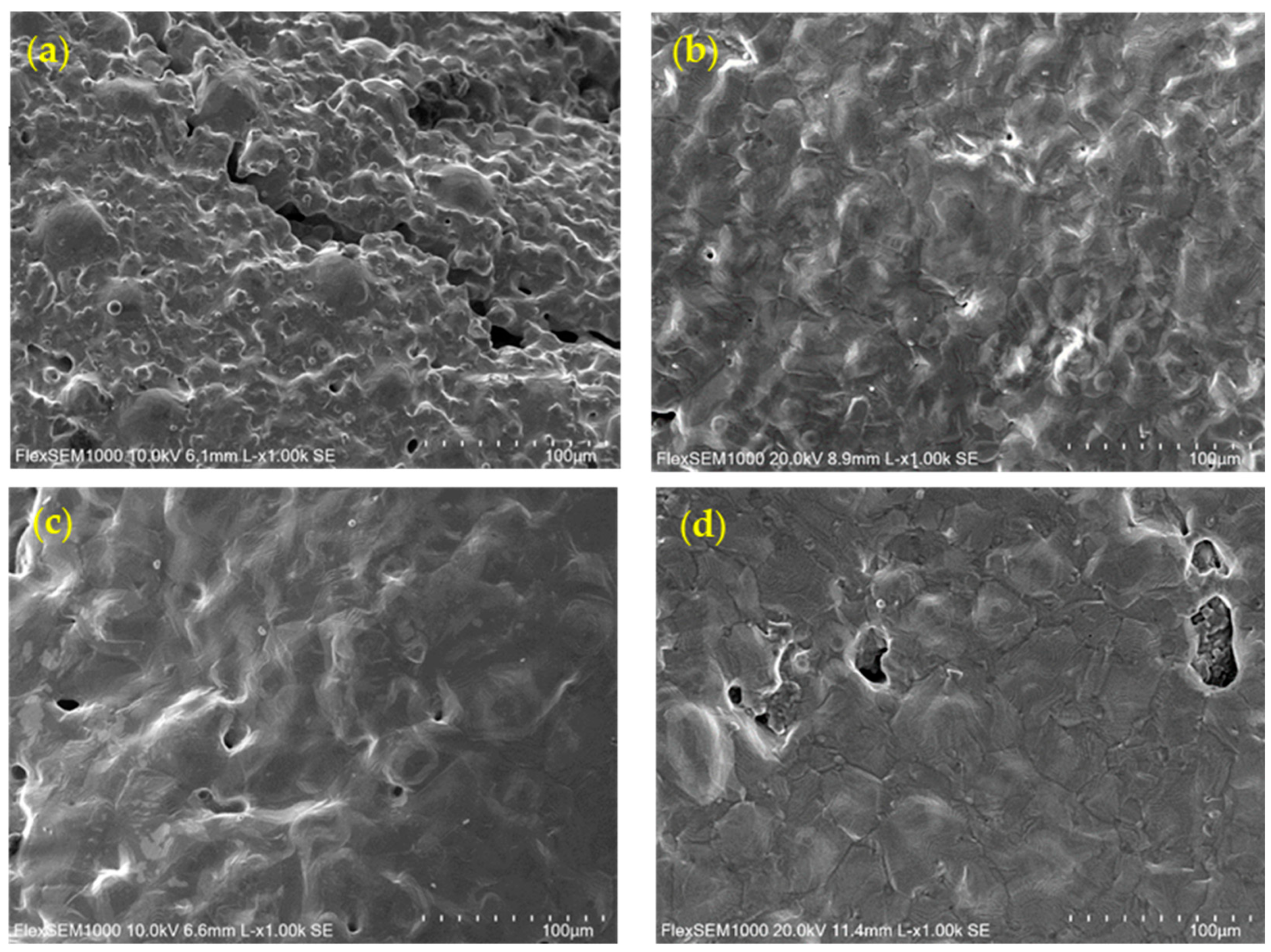

3.1. Microstructure and Phase Evolution

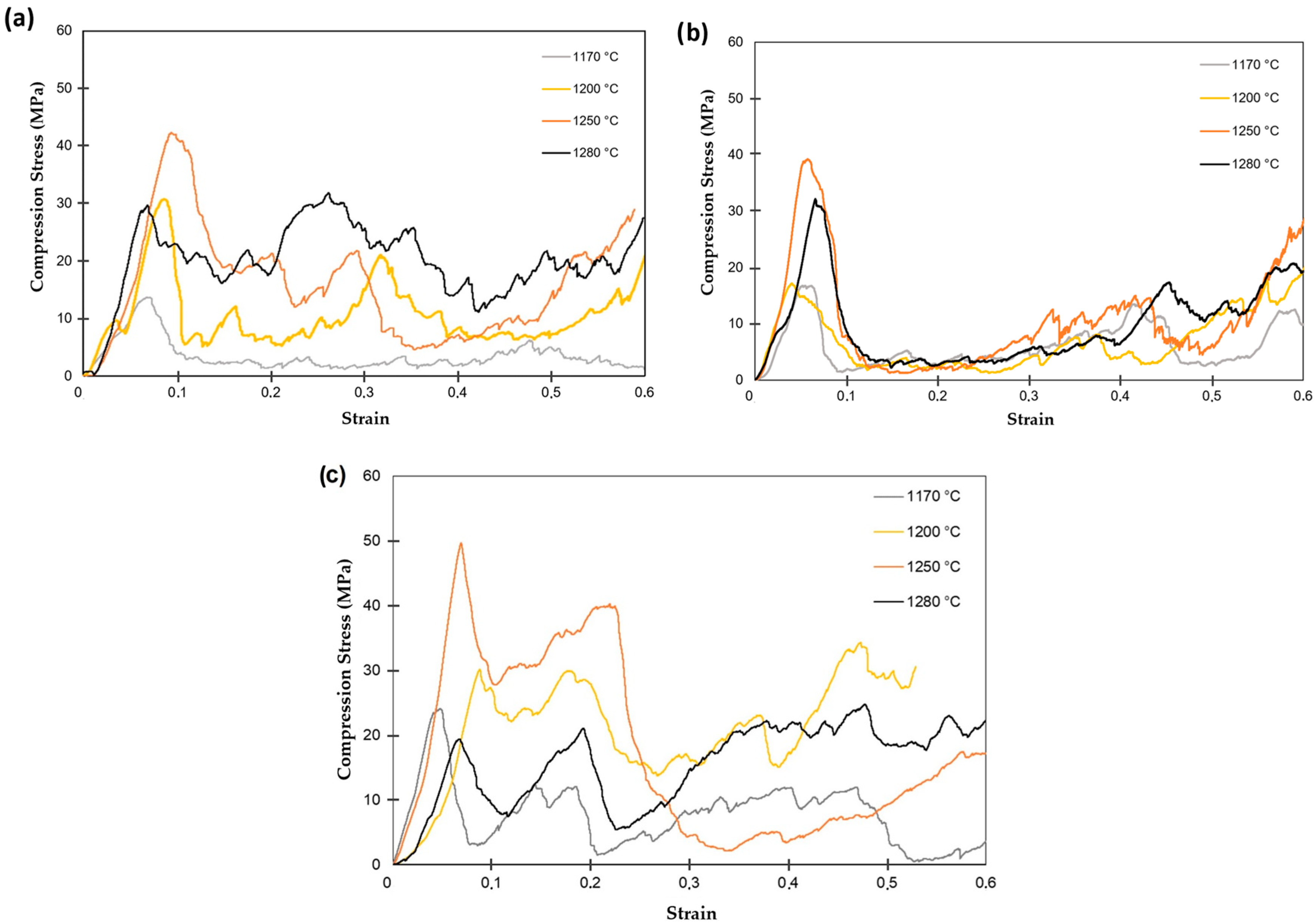

3.2. Mechanical Properties

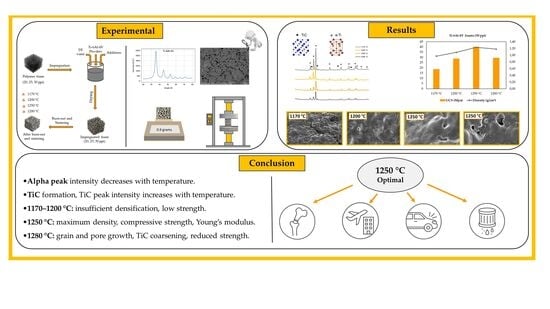

4. Conclusions

- SEM analysis showed that sintering at 1250 °C provided the best balance between densification and pore structural integrity. At lower temperatures, bond formation remained incomplete due to relatively limited atomic diffusion, whereas excessive sintering at 1280 °C led to grain growth and pore coarsening, resulting in reduced mechanical performance.

- XRD and EDS analyses confirmed the presence of the TiC phase, formed through the reaction between titanium and residual carbon. Microstructural analyses revealed that TiC particles became significantly larger as the sintering temperature increased. The increase in TiC peak intensity in XRD patterns also supports this growth. The average TiC particle size increased from 5.63 µm at 1170 °C to 9.28 µm at 1280 °C. Up to 1250 °C, this growth did not negatively affect mechanical strength; on the contrary, strength values increased with rising temperature.

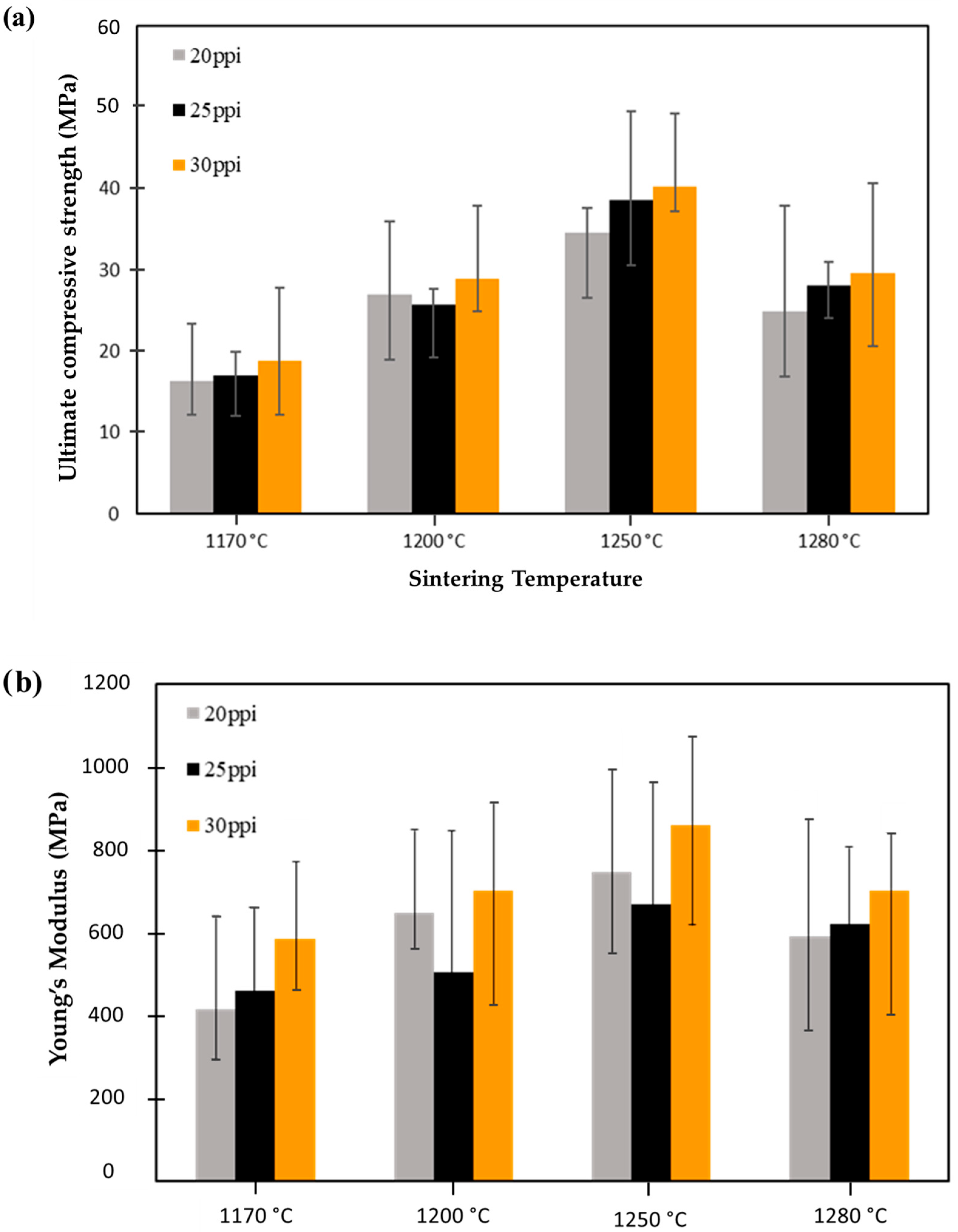

- Mechanical tests showed that compressive strength and elastic modulus improved with increasing temperature up to 1250 °C and reached maximum values of 40.2 MPa and 858.9 MPa, respectively. However, a decrease was observed in these values at 1280 °C due to microstructural deteriorations.

- Although pore size had a limited effect on mechanical behavior, the foams produced using the 30 ppi template exhibited relatively higher strength values, which can be attributed to their more uniform and regular pore structure.

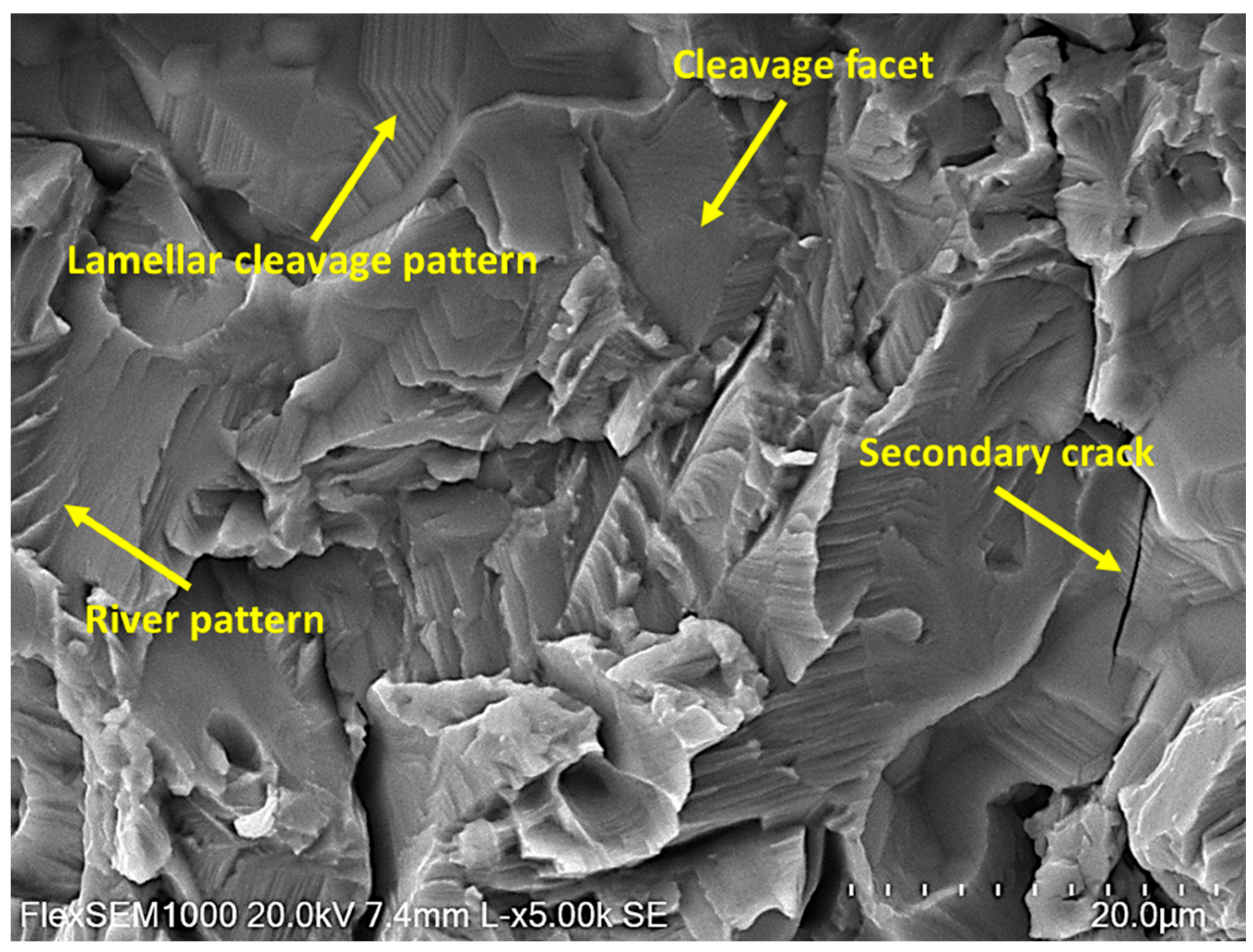

- Gibson-Ashby analysis and fracture surface observations revealed that the Ti-6Al-4V foams exhibited brittle behavior. The high strength exponent (m = 3.38), together with cleavage like facets, river patterns, lamellar cleavage patterns, and secondary cracks, indicates that this brittleness is associated with stress concentrations arising from TiC particles and the cracks formed in the foam after sintering.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DI water | Deionized water |

| E | Young’s modulus (elastic modulus) |

| ECD | Equivalent circular diameter |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| hcp | Hexagonal close-packed |

| ICDD | International Centre for Diffraction Data |

| MC | Methyl cellulose |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| ppi | Pores per inch |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TiC | Titanium carbide |

| UCS | Ultimate Compressive Strength |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| β-phase | Beta phase (body-centered cubic titanium phase) |

References

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781139878326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, A.; Ao, Q.; Wu, C.; Ma, J.; Cao, P. Energy absorption characteristics and preparation of porous titanium with high porosity. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleistein, T.; Diebels, S.; Jung, A. Parameter identification for open cell aluminium foams using inverse calculation. Comput. Math. Appl. 2020, 79, 2644–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, G.C.; Yener, T.; Ozcelik, G.; Ozkan, H. TiB-based coating formation on Ti6Al4V alloy. Mater. Test. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, J.; Starly, B.; Raman, S.; Christensen, A. Mechanical evaluation of porous titanium (Ti6Al4V) structures with electron beam melting (EBM). J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2010, 3, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, Z.; Bor, Ş. Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V alloy foams synthesized by space holder technique. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiołek, A.; Zimowski, S.; Kopia, A.; Moskalewicz, T. The influence of electrophoretic deposition parameters and heat treatment on the microstructure and tribological properties of nanocomposite Si3N4/PEEK 708 coatings on titanium alloy. Coatings 2019, 9, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáquez-Muñoz, J.M.; Rosales-Leal, J.I.; Martínez-Ramos, C.; Casado-Carmona, F.A.; Ojeda, R.; Saldaña, L.; Gallardo-Moreno, A.M. Electrochemical corrosion of titanium and titanium alloys anodized in H2SO4 and H3PO4 solutions. Coatings 2022, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.; Pandit, A.; Apatsidis, D.P. Fabrication methods of porous metals for use in orthopaedic applications. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Alnaser, I.A. A review of different manufacturing methods of metallic foams. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 6280–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Guercio, G.; Galati, M.; Saboori, A. Innovative approach to evaluate the mechanical performance of Ti–6Al–4V lattice structures produced by electron beam melting process. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, F.; Noelke, C.; Kaierle, S.; Haferkamp, H.; Gesing, T.M. Influence of Foaming Agents on Laser Based Manufacturing of Closed-cell Ti Foam. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 4, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manonukul, A.; Srikudvien, P.; Tange, M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of commercially pure titanium foam with varied cell size fabricated by replica impregnation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 650, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.Y.; Alvarez, O.A.; Escobar, J.A.; Neto, J.B.R.; Rambo, C.R.; Hotza, D. Relationship between rheological behaviour and final structure of Al2O3 and YSZ foams produced by replica. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 2012, 549508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tange, M.; Manonukul, A.; Srikudvien, P. The effects of organic template and thickening agent on structure and mechanical properties of titanium foam fabricated by replica impregnation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 641, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Zhang, L.C.; Huang, L.; Sercombe, T.B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. In situ formation of Ti alloy/TiC porous composites by rapid microwave sintering of Ti6Al4V/MWCNTs powder. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 557, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülenç, İ.T.; Bai, M.; Mitchell, R.L.; Todd, I.; Inkson, B.J. In situ TiC reinforced Ti6Al4V matrix composites manufactured via selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Van Blitterswijk, C.A.; De Groot, K. Factors having influence on the rheological properties of Ti6A14V slurry. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Implants for Surgery-Metallic Materials-Part 3: Wrought Titanium 6-Aluminium 4-Vanadium Alloy Implants Chirurgicaux-Matériaux Métalliques. 2021. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/ad76586a-4754-4cee-8e09- (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; DeZonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.P.; Li, S.H.; Van Blitterswijk, C.A.; De Groot, K. A novel porous Ti6Al4V: Characterization and cell attachment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 73, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, C.; Kotlarz, M.; Gonçalves, I.F.; Lally, C.; Kelly, D.J. Chemical etching of Ti-6Al-4V biomaterials fabricated by selective laser melting enhances mesenchymal stromal cell mineralization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2024, 112, 1548–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, G.A.; Salinas-Rodríguez, E. Realistic particle size distributions during sintering by Ostwald ripening. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2001, 139, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Doherty, R.D.; Cantor, B. Stability of Microstructure in Metallic Systems, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, F.J.; Planell, J.A. Behaviour of normal grain growth kinetics in single phase titanium and titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 283, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.M. Coarsening in sintering: Grain shape distribution, grain size distribution, and grain growth kinetics in solid-pore systems. Crit. Rev. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2010, 35, 263–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengucci, P.; Gatto, A.; Bassoli, E.; Denti, L.; Fiori, F.; Girardin, E.; Bastianoni, P.; Rutkowski, B.; Czyrska-Filemonowicz, A.; Barucca, G. Effects of build orientation and element partitioning on microstructure and mechanical properties of biomedical Ti-6Al-4V alloy produced by laser sintering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, A. Comment on ‘MoS2/Ti3C2 heterostructure for efficient visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 13559–13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Kumar, S.; Dawari, A.; Kirwai, S.; Patil, A.; Singh, R. Effect of Temperature and Cooling Rates on the α+β Morphology of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 14, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarín, P.; Gualo, A.; Simón, A.G.; Piris, N.M.; Badía, J.M. Study of Alpha-Beta Transformation in Ti-6Al-4V-ELI. Mechanical and Microstructural Characteristics. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 638–642, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.Y.; Li, S.J.; Murr, L.E.; Zhang, Z.B.; Hao, Y.L.; Yang, R.; Medina, F.; Wicker, R.B. Compression deformation behavior of Ti-6Al-4V alloy with cellular structures fabricated by electron beam melting. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 16, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Luo, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, T. Effect of sintering temperature on the mechanical properties and microstructures of pressure-less-sintered B4C/SiC ceramic composite with carbon additive. J. Alloys Compd 2020, 820, 153153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergül, E.; Gülsoy, H.O.; Günay, V. Effect of sintering parameters on mechanical properties of injection moulded Ti-6Al-4V alloys. Powder Metall. 2009, 52, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S.; Shmeliov, A.; Nicolosi, V.; Dowling, D.P. Investigation of process by-products during the Selective Laser Melting of Ti6AL4V powder. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gölbaşı, Z.; Öztürk, B.; Üllen, N.B. The structural and mechanical properties of open-cell aluminum foams: Dependency on porosity, pore size, and ceramic particle addition. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, T.; Zhan, S.; Chen, X.; Hu, L. Effect of Sintering Temperature on Microstructure Characteristics of Porous NiTi Alloy Fabricated via Elemental Powder Sintering. Materials 2024, 17, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazic, B.; Abali, B.E.; Yang, H.; Newell, P. Mechanical analysis of heterogeneous materials with higher-order parameters. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 5051–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Hernández, J.O.; Suarez, M.A.; Goodall, R.; Lara-Rodriguez, G.A.; Alfonso, I.; Figueroa, I.A. Manufacturing of open-cell Mg foams by replication process and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2014, 64, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benac, D.J.; Cherolis, N.; Wood, D. Managing Cold Temperature and Brittle Fracture Hazards in Pressure Vessels. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2016, 16, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Fan, L.; Wang, Q.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. The role of the bainitic packet in control of impact toughness in a simulated CGHAZ of X90 pipeline steel. Metals 2016, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J. Study on the Effect of Negative Temperature Change on the Fracture Morphology of Granite under Impact. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 4918680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti | Al | V | Fe | C | N | H | O | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition of As Received Powders (wt. %) | Balance | 6.38 | 4.12 | 0.19 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.0023 | 0.075 |

| ISO 5832-3:2021 (wt. %) | Balance | 5.50–6.75 | 3.50–4.50 | ≤0.3 | ≤0.08 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.2 |

| Particle Size Distribution | D10 | D50 | D90 | D97 |

| Powder (Ti-6Al-4V) | 2.4 | 4.8 | 9.2 | 11.1 |

| Sintering Temperature | 1170 °C | 1200 °C | 1250 °C | 1280 °C |

| TiC Diameter (µm) | 5.6 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 9.3 |

| α-Ti Grains (µm) | 17.2 | 23.7 | 28.8 | 32.1 |

| Sintering Temperature | Cell Size | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | UCS (MPa) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1170 °C | 20 ppi | 415.5 ± 175.7 | 16.3 ± 5.04 | 1.073 ± 0.051 |

| 25 ppi | 459.8 ± 160.2 | 16.9 ± 3.34 | 1.1045 ± 0.124 | |

| 30 ppi | 584.1 ± 185.7 | 18.7 ± 8.82 | 0.975 ± 0.097 | |

| 1200 °C | 20 ppi | 647.5 ± 172.9 | 26.8 ± 8.58 | 1.063 ± 0.066 |

| 25 ppi | 504.0 ± 272.0 | 25.6 ± 3.74 | 1.067 ± 0.007 | |

| 30 ppi | 702.4 ± 278.5 | 28.0 ± 7.45 | 1.081 ± 0.303 | |

| 1250 °C | 20 ppi | 745.2 ± 222.0 | 34.5 ± 5.52 | 1.114 ± 0.246 |

| 25 ppi | 667.6 ± 331.6 | 38.5 ± 12.82 | 1.154 ± 0.084 | |

| 30 ppi | 858.9 ± 256.6 | 40.2 ± 7.12 | 1.234 ± 0.195 | |

| 1280 °C | 20 ppi | 590.8 ± 325.2 | 24.8 ± 10.31 | 1.109 ± 0.058 |

| 25 ppi | 620.9 ± 301.4 | 28.0 ± 1.55 | 1.122 ± 0.115 | |

| 30 ppi | 700.2 ± 225.6 | 29.6 ± 9.56 | 1.181 ± 0.204 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

İnan Üstün, A.; Okuyucu, H. Production and Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V Foams Produced by the Replica Impregnation Method. Metals 2025, 15, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121354

İnan Üstün A, Okuyucu H. Production and Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V Foams Produced by the Replica Impregnation Method. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121354

Chicago/Turabian Styleİnan Üstün, Aynur, and Hasan Okuyucu. 2025. "Production and Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V Foams Produced by the Replica Impregnation Method" Metals 15, no. 12: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121354

APA Styleİnan Üstün, A., & Okuyucu, H. (2025). Production and Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V Foams Produced by the Replica Impregnation Method. Metals, 15(12), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121354