Fabrication and Thermomechanical Processing of a Microalloyed Steel Containing In Situ TiB2 Particles for Automotive Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

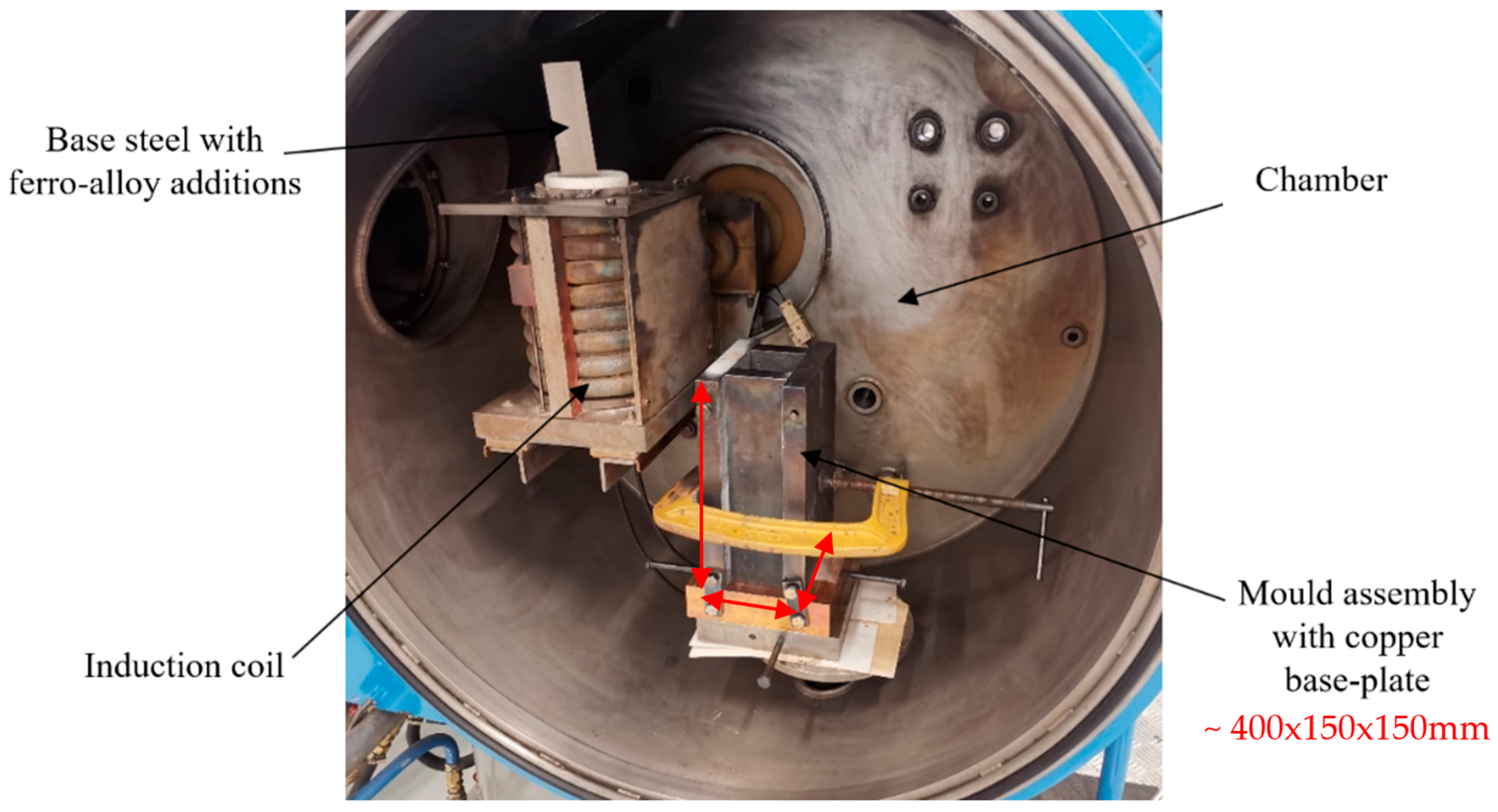

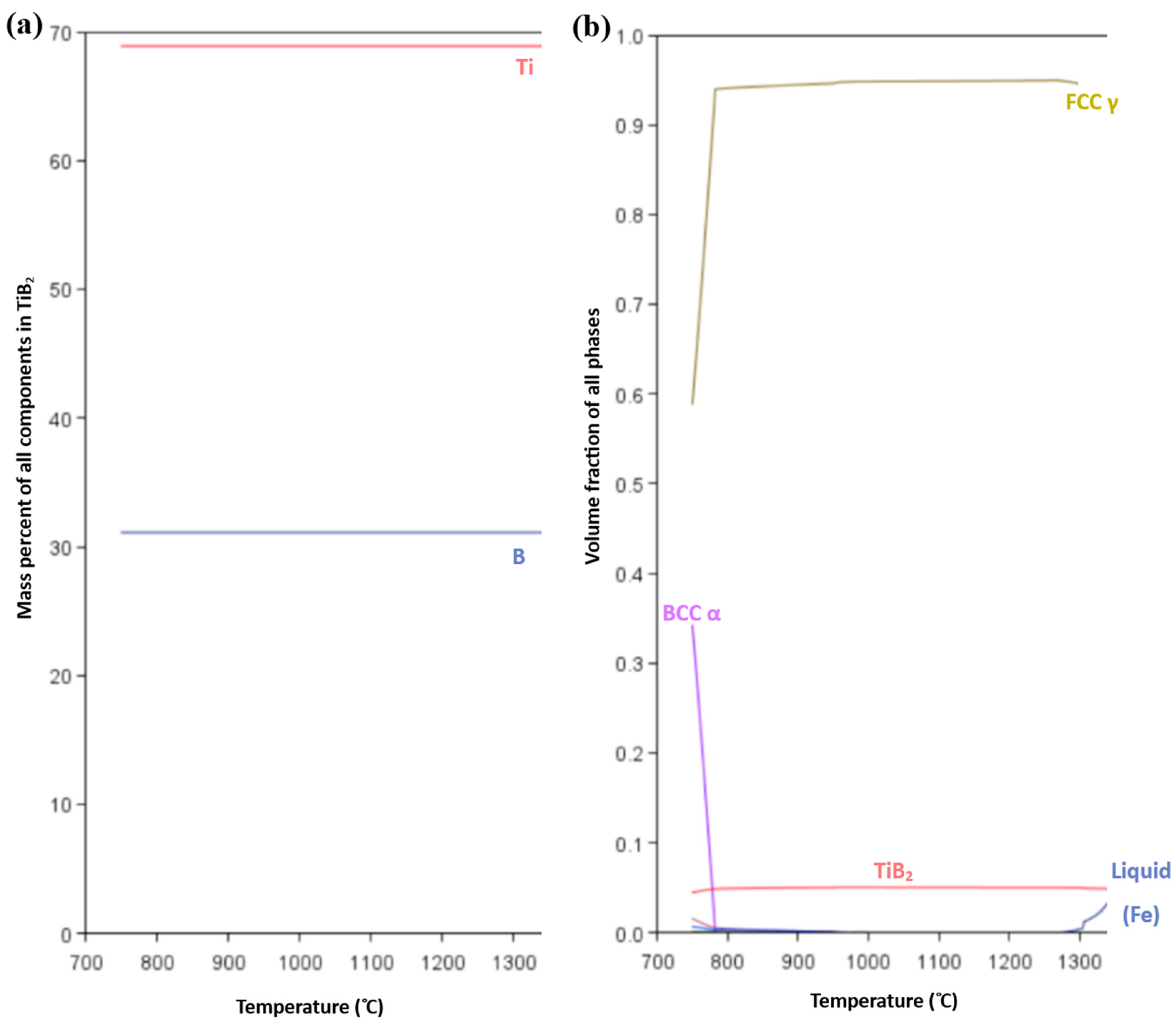

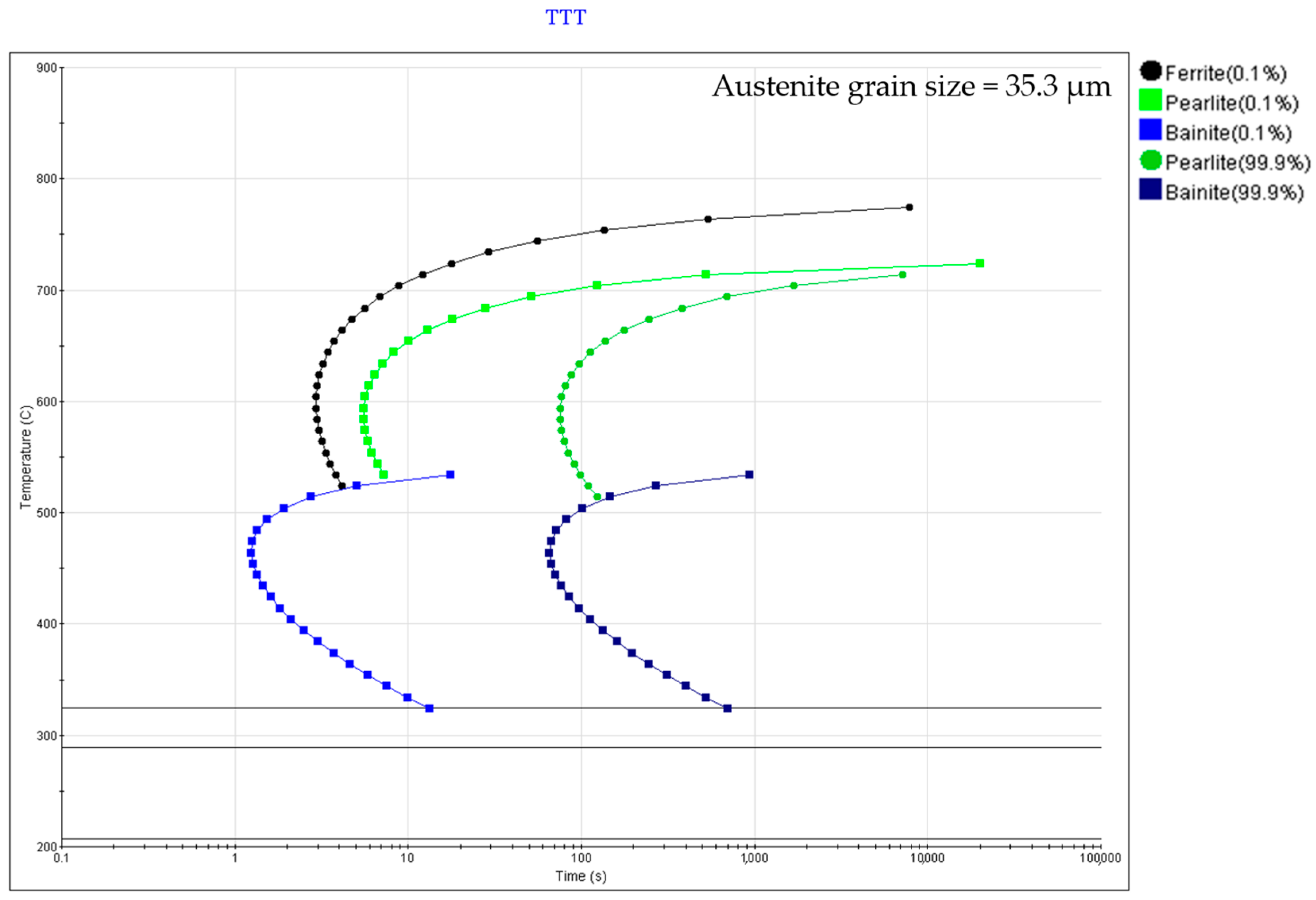

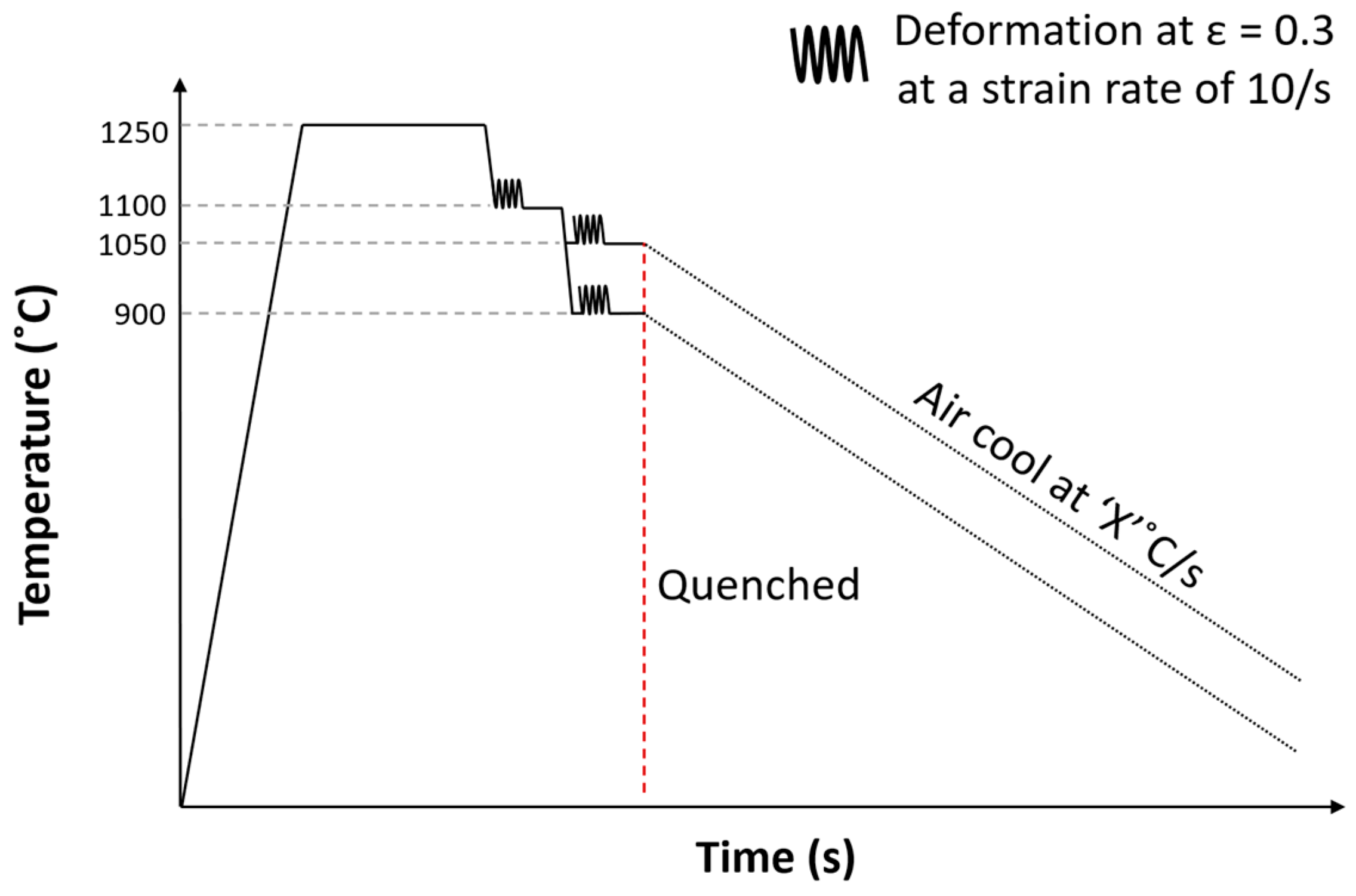

2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Flow Behaviour

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

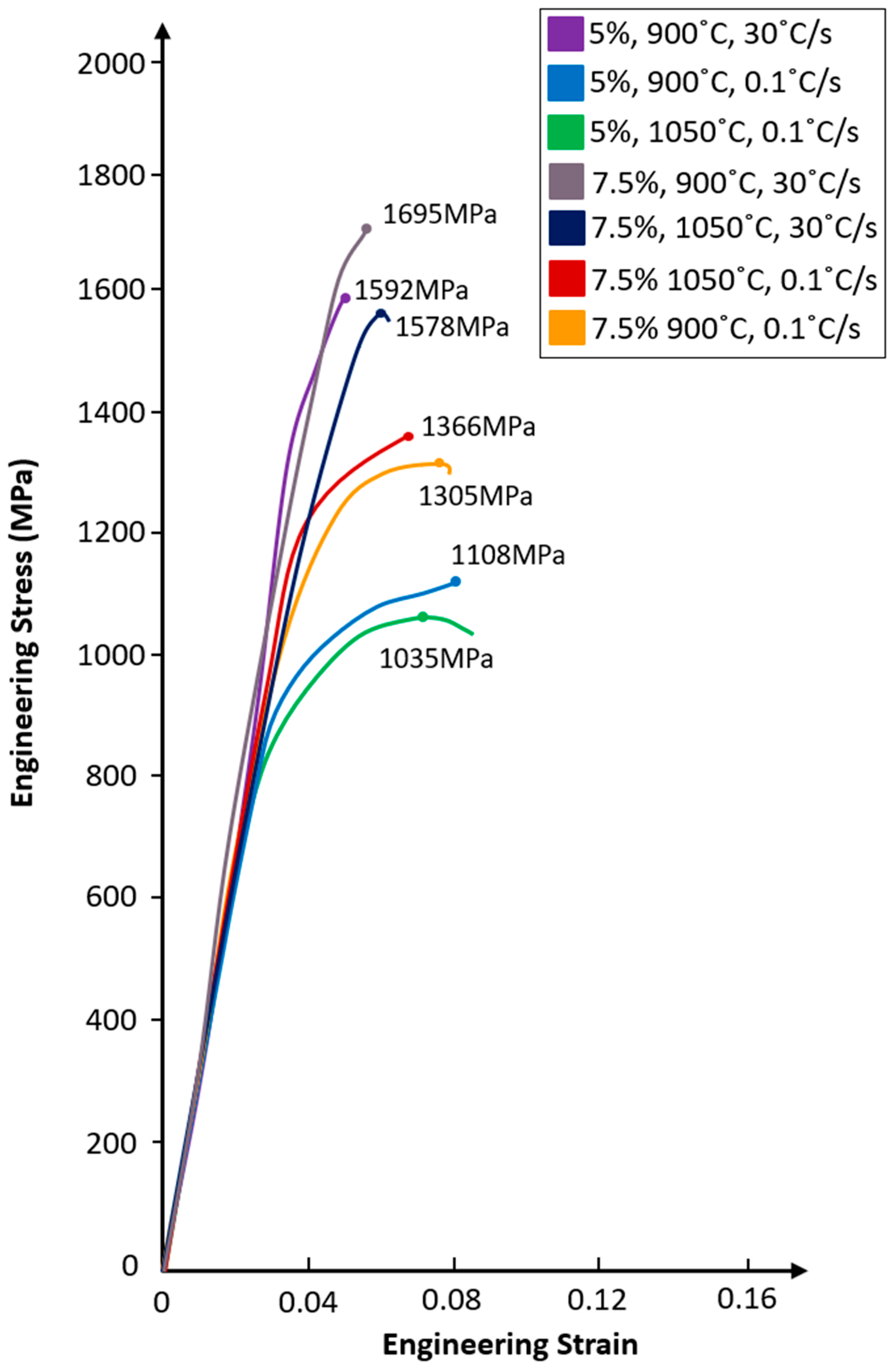

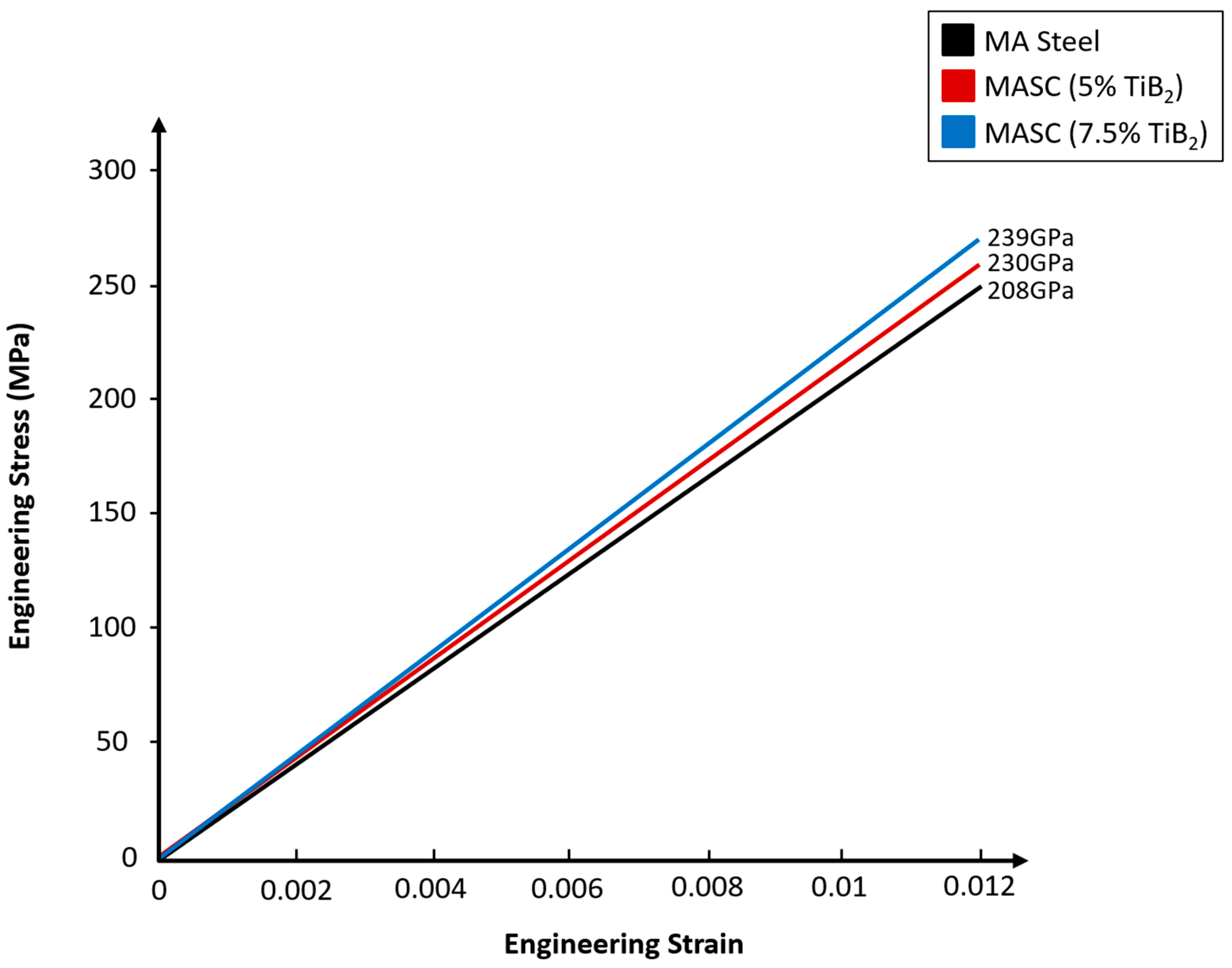

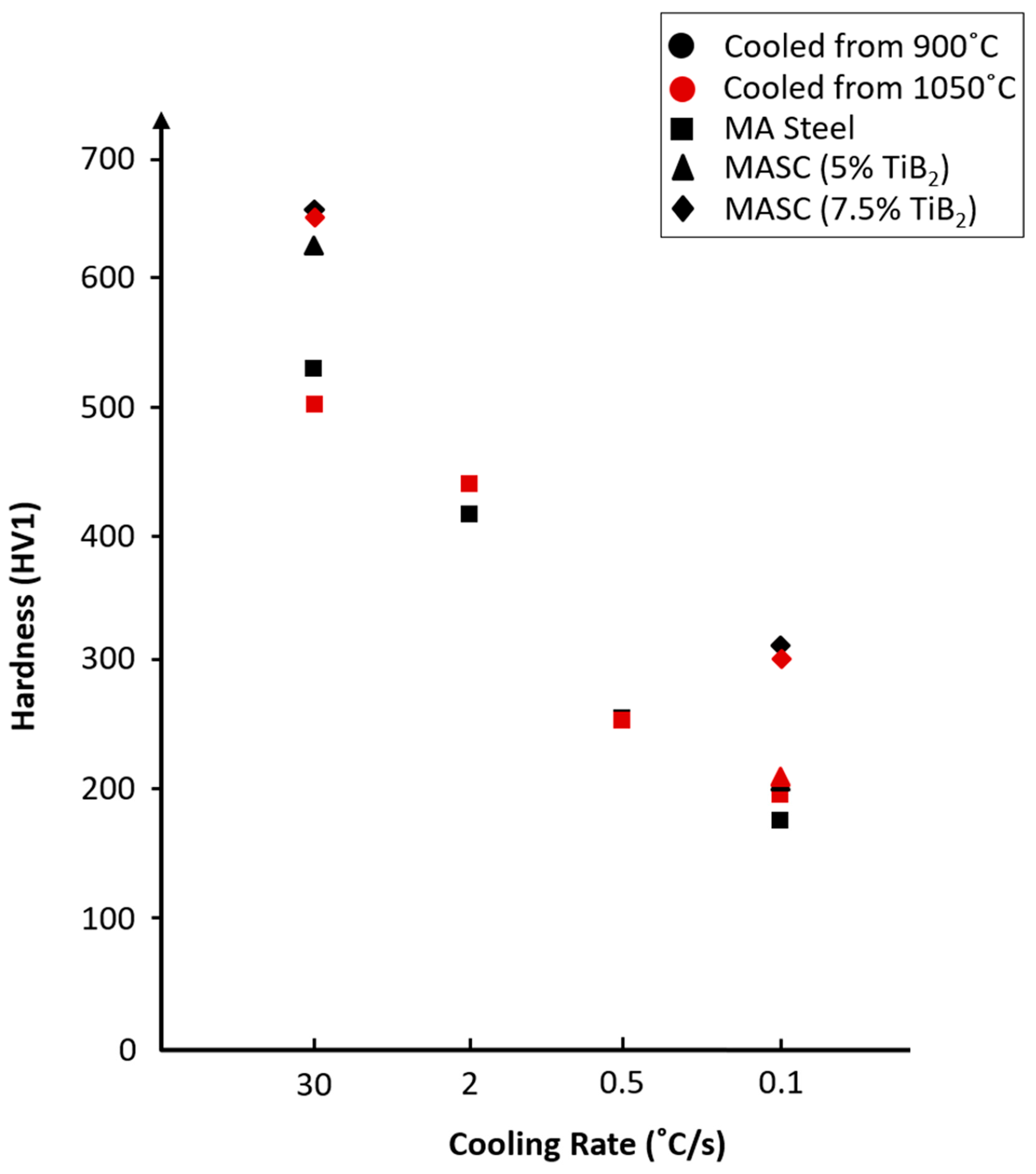

3.3. Mechanical Testing

4. Conclusions

- The interface between TiB2 and matrix remains stable even at elevated temperatures, with grain pinning mechanisms notably effective in the 5MASC alloy, particularly when cooled at 0.1 °C/s from 1050 °C. The pinning effect is evidenced by the retention of elongated grains aligned in the rolling direction, which remains consistent at higher temperatures.

- At a cooling rate of 30 °C/s, both alloys develop a martensitic matrix, with the TiB2 particles remaining unaffected. However, when the cooling rate is reduced to 0.1 °C/s, which can be observed in heavy sections, the 5MASC alloy displays polygonal ferrite and incomplete transformation of pearlite. In contrast, the 7.5MASC alloy at this slower cooling rate does not exhibit the same phase transformation. Instead, it shows the nucleation of polygonal ferrite without the presence of pearlite. This variation could be attributed to the presence and thermodynamic impact of higher-volume fractions of TiB2, which may alter the phase stability and transformation kinetics.

- Tensile testing and RFDA results revealed improvements in the modulus of elasticity, from 208 GPa for the base MA steel to 230 GPa and 239 GPa for the 5MASC and 7.5MASC alloys, respectively. This demonstrates the effect of increasing TiB2 volume fraction on enhancing the material’s stiffness. The progressive improvement in modulus reflects the reinforcing role of TiB2, contributing to the overall mechanical performance of the alloys.

- The primary objective of this study was to enhance the stiffness and strength of MA steel through ceramic reinforcement. The tensile results, particularly under conditions that mirror real-life applications where stiffness, yield strength, and uniform elongation are paramount, indicate that the 5MASC alloy cooled from 900 °C at 0.1 °C/s achieves an optimal yield strength of 905 MPa, coupled with a uniform elongation of 8%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.Z.; Huang, M.X. Revealing the interfacial plasticity and shear strength of a TiB2-strengthened high-modulus low-density steel. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2018, 121, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Jiang, C. In situ experimental study on fracture toughness and damage mechanism of TiB2-reinforced steel matrix composites. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2023, 46, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda Salustre, M.G.; Gonoring, T.B.; Martins, J.B.R.; Lopes, H.D.A.; Orlando, M.T.D.A. Study of steel matrix composite samples with 12%Wt TiB2 produced by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 302, 127736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Springer, H.; Aparicio-Fernández, R.; Raabe, D. Improving the mechanical properties of Fe–TiB2 high modulus steels through controlled solidification processes. Acta Mater. 2016, 118, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Saito, T. Phase equilibria in TiB2-reinforced high modulus steel. J. Phase Equilibria 1999, 20, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleck, W.; Bambach, M.; Wirths, V.; Stieben, A. Microalloyed engineering steels with improved performance—An overview. HTM-J. Heat. Treat. Mater. 2017, 72, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.H.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Cao, H.; Gao, S.J.; Li, J. Fabrication of in situ TiB2 reinforced steel matrix composite by vacuum induction melting and its microstructure and tensile properties. Int. J. Cast. Met. Res. 2010, 23, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, F.; Daeschler, V.; Petitgand, G. High modulus steels: New requirement of automotive market. How to take up challeng? Can. Metall. Q. 2014, 53, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong, S.C.; Wang, G.S.; Mai, Y.W. Erratum to ‘Low-cycle fatigue behavior of Al-based composites containing in situ TiB2, Al2O3 and Al3Ti reinforcements’ [Mater. Sci. Eng. A 358 (1–2) (2003) 99–106]. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 366, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhasivam, M.; Sankaranarayanan, S.R.; Babu, S.P.K. Synthesis and characterization of TiB2 reinforced AISI 420 stainless steel composite through vacuum induction melting technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 22, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, B.; Xu, K. Effect of particle morphology on fatigue crack propagation mechanism of TiB2-reinforced steel matrix composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 274, 127736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiere, E.J.; Garcia, C.I.; DeArdo, A.J. The Influence of Niobium Supersaturation in Austenite on the Static Recrystallisation Behaviour of Low Carbon Microalloyed Steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1996, 27A, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengaroni, S.; Calderini, M.; Napoli, G.; Zitelli, C.; Di Schino, A. Micro-alloyed steel for forgings. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 941, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guk, S.; Milisova, D.; Pranke, K. Influence of deformation conditions on the microstructure and formability of sintered Mg-PSZ reinforced TRIP-matrix-composites. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 684, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, M.S.; Mahon, G.J.; Roebuck, B.; Lacey, A.J.; Palmiere, E.J.; Sellars, C.M.; van der Winden, M.R. Measurement of flow stress in hot plane strain compression tests. Mater. High. Temp. 2006, 23, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttner, S.; Merklein, M. A new approach for the determination of the linear elastic modulus from uniaxial tensile tests of sheet metals. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2017, 241, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aegerter, J.; Kühn, H.-J.; Frenz, H.; Weißmüller, C. EN ISO 6892-1:2009; Tensile Testing: Initial Experience from the Practical Implementation of the New Standard. De Gruyter Brill: Marl, Germany, 2011.

- Munro, R.G. Material Properties of Titanium Diboride. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2000, 105, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K. Ultra High Modulus Steel Reinforced with Titanium Boride Particles. R&D Rev. Toyota CRDL 2000, 35, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhasivam, M.; Mohan, N.; Sankaranarayanan, S.R.; Babu, S.P.K. Investigation on mechanical and tribological behaviour of titanium diboride reinforced martensitic stainless steel. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 7, 016545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Li, J.; Shi, C.B.; Huo, X.D. Effect of Boron and Titanium Addition on the Hot Ductility of Low-Carbon Nb-Containing Steel. High. Temp. Mater. Process. 2015, 34, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, C.; Springer, H.; Raabe, D. Efficient liquid metallurgy synthesis of Fe-TiB2 high modulus steels via in-situ reduction of titanium oxides. Mater. Des. 2016, 97, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Fe | C | Cr | Mn | Mo | Nb | Ni | P | S | Si | Ti | V | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA Steel | 96.56 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 1.37 | 0.06 | 0.030 | 0.17 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.18 | -- |

| 5MASC | 94.021 | 0.43 | 0.10 | 1.28 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.70 | 2.05 | 0.18 | 0.95 |

| 7.5MASC | 92.991 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 1.29 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.75 | 2.55 | 0.19 | 1.45 |

| Material | Temp. (°C) of PSC Sample | Cooling Rate (°C/s) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Uniform Elongation (%) | Standard Deviation (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5MASC | 900 | 30 | 1302 | 5.1 | 24.5 |

| 900 | 0.1 | 905 | 8.0 | 17.8 | |

| 1050 | 0.1 | 869 | 7.6 | 15.3 | |

| 7.5MASC | 900 | 30 | 1657 | 5.8 | 32.7 |

| 1050 | 30 | 1380 | 6.1 | 26.1 | |

| 900 | 0.1 | 1104 | 7.2 | 19.9 | |

| 1050 | 0.1 | 1153 | 7.8 | 16.5 |

| Material | Temp. (°C) of PSC Sample | Cooling Rate (°C/s) | The Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Vickers Hardness (HV1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5MASC | 900 | 30 | 229 | 624.2 |

| 900 | 0.1 | 206.9 | ||

| 1050 | 0.1 | 204.9 | ||

| 1150 | 0.1 | 187.4 | ||

| 7.5MASC | 900 | 30 | 235 | 668.8 |

| 1050 | 30 | 664.7 | ||

| 900 | 0.1 | 314.1 | ||

| 1050 | 0.1 | 302.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, S.; Azakli, Y.; Pulfrey, W.; Naeth, O.; Rablbauer, R.; Jackson, M.; Palmiere, E.J. Fabrication and Thermomechanical Processing of a Microalloyed Steel Containing In Situ TiB2 Particles for Automotive Applications. Metals 2025, 15, 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121322

Khan S, Azakli Y, Pulfrey W, Naeth O, Rablbauer R, Jackson M, Palmiere EJ. Fabrication and Thermomechanical Processing of a Microalloyed Steel Containing In Situ TiB2 Particles for Automotive Applications. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121322

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Sulayman, Yunus Azakli, William Pulfrey, Oliver Naeth, Ralf Rablbauer, Martin Jackson, and Eric J. Palmiere. 2025. "Fabrication and Thermomechanical Processing of a Microalloyed Steel Containing In Situ TiB2 Particles for Automotive Applications" Metals 15, no. 12: 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121322

APA StyleKhan, S., Azakli, Y., Pulfrey, W., Naeth, O., Rablbauer, R., Jackson, M., & Palmiere, E. J. (2025). Fabrication and Thermomechanical Processing of a Microalloyed Steel Containing In Situ TiB2 Particles for Automotive Applications. Metals, 15(12), 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121322