Mechanistic Insights into the Effect of Ca on the Oxidation Behavior of Fe3O4: A Combined DFT and AIMD Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods and Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calculation Parameter Convergence Test

3.1.1. K-Point Test

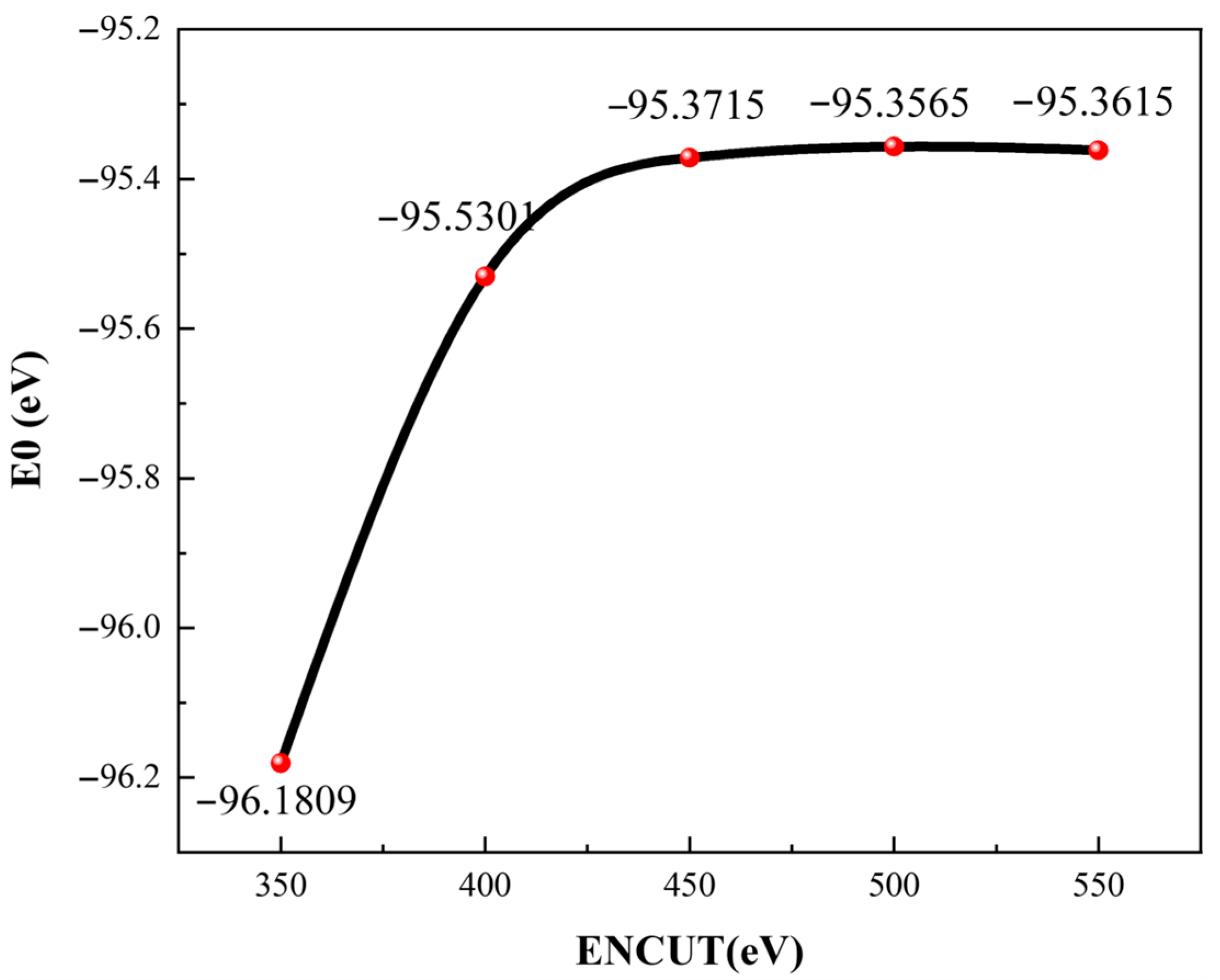

3.1.2. ENCUT Test

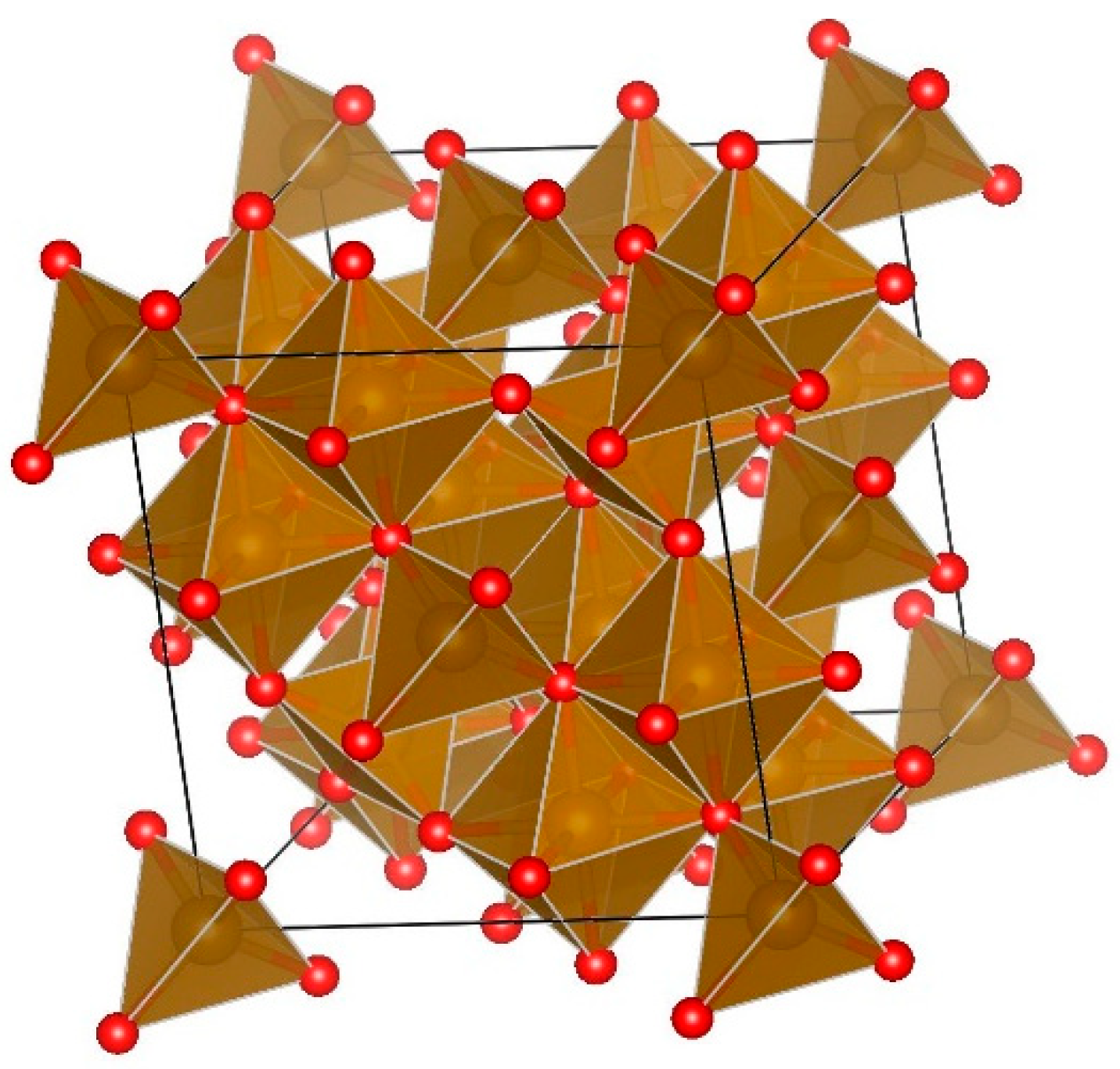

3.1.3. Determination of Lattice Parameters

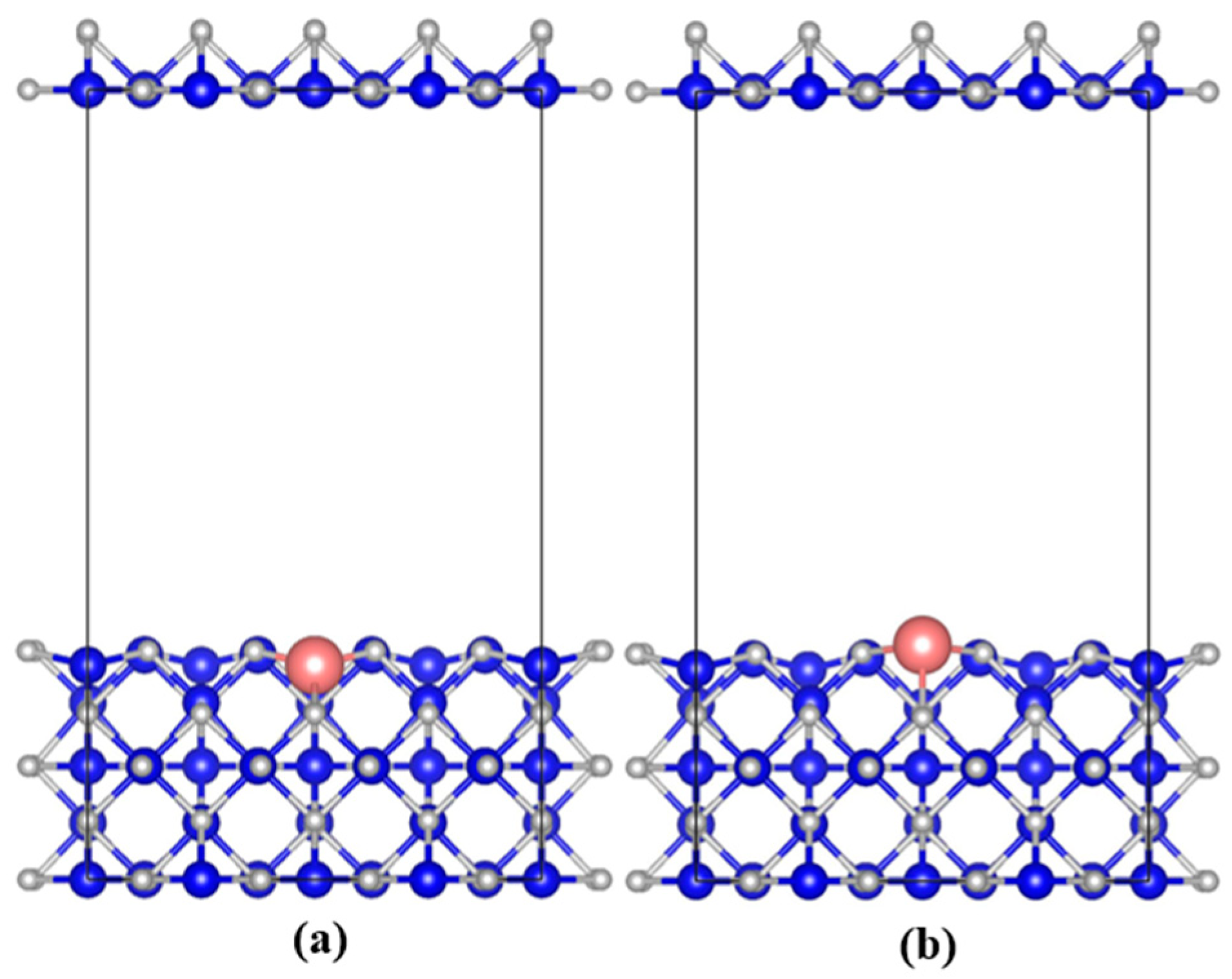

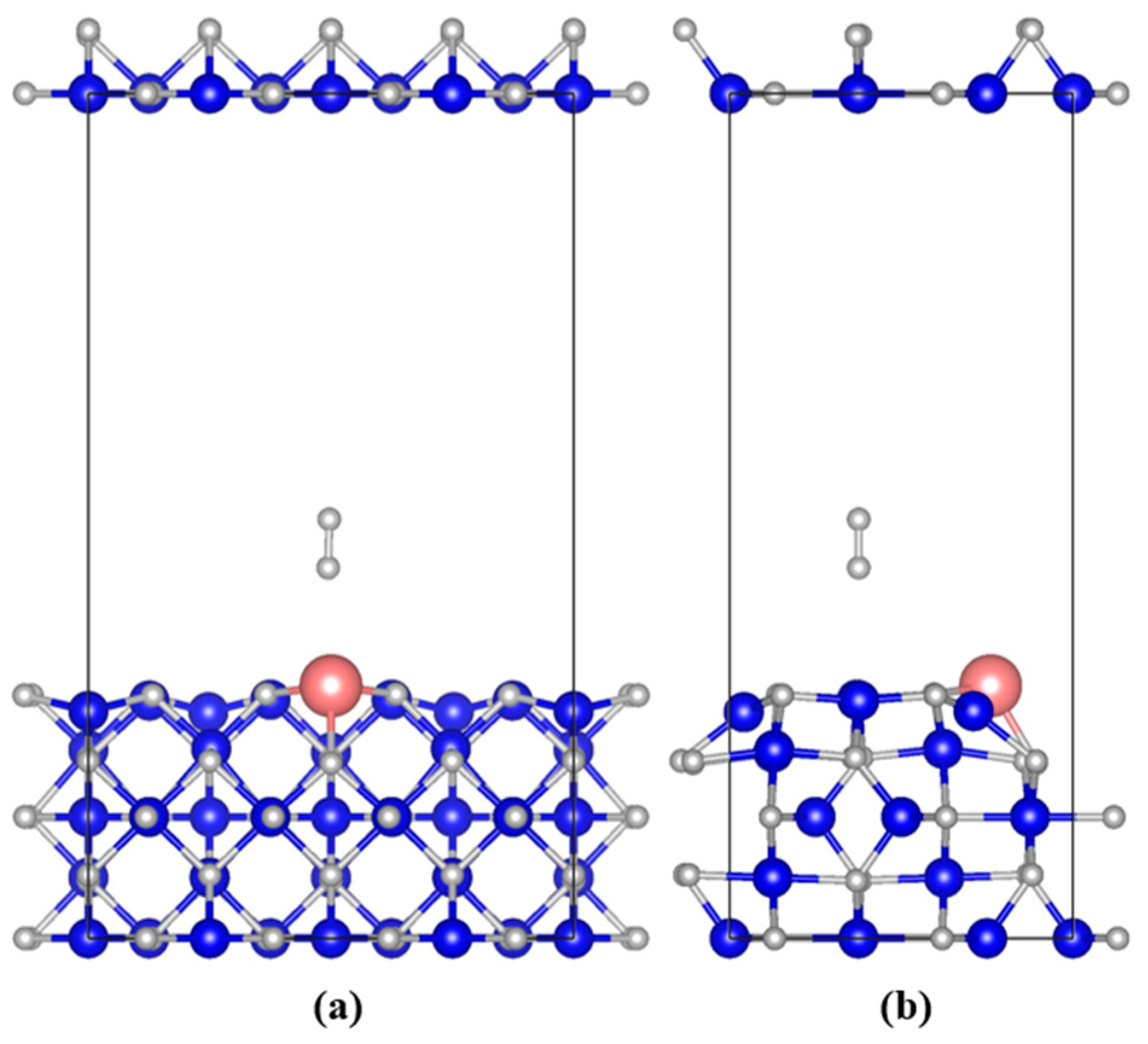

3.2. AIMD Simulation of Surface Adsorption System

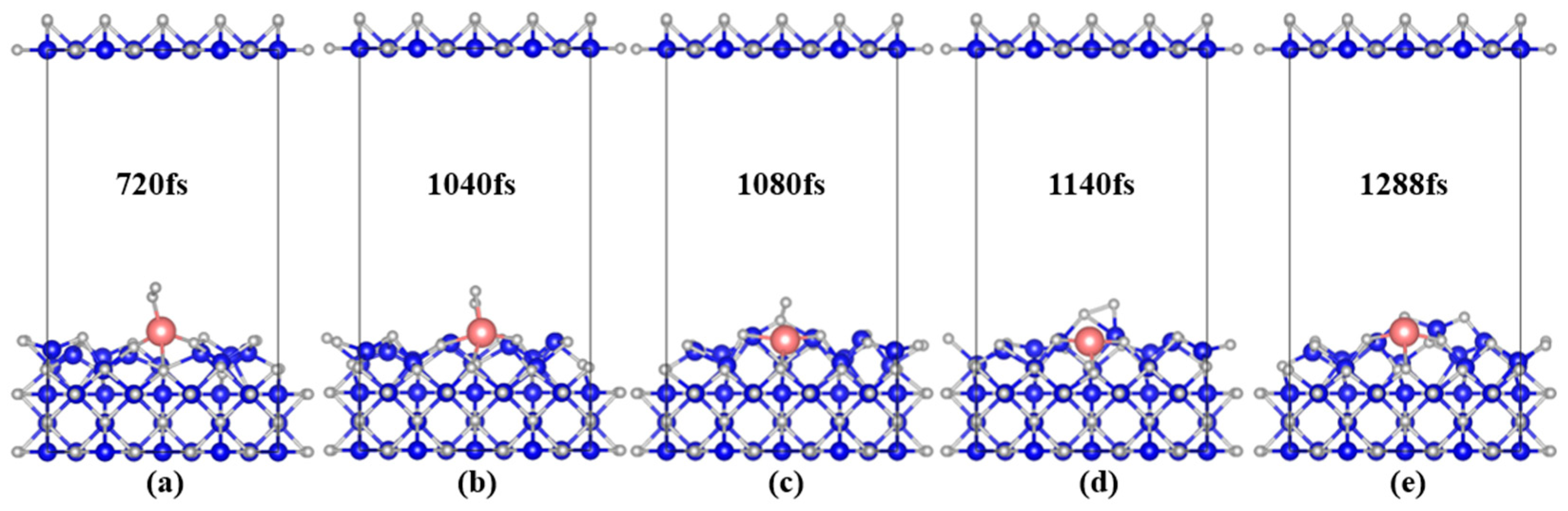

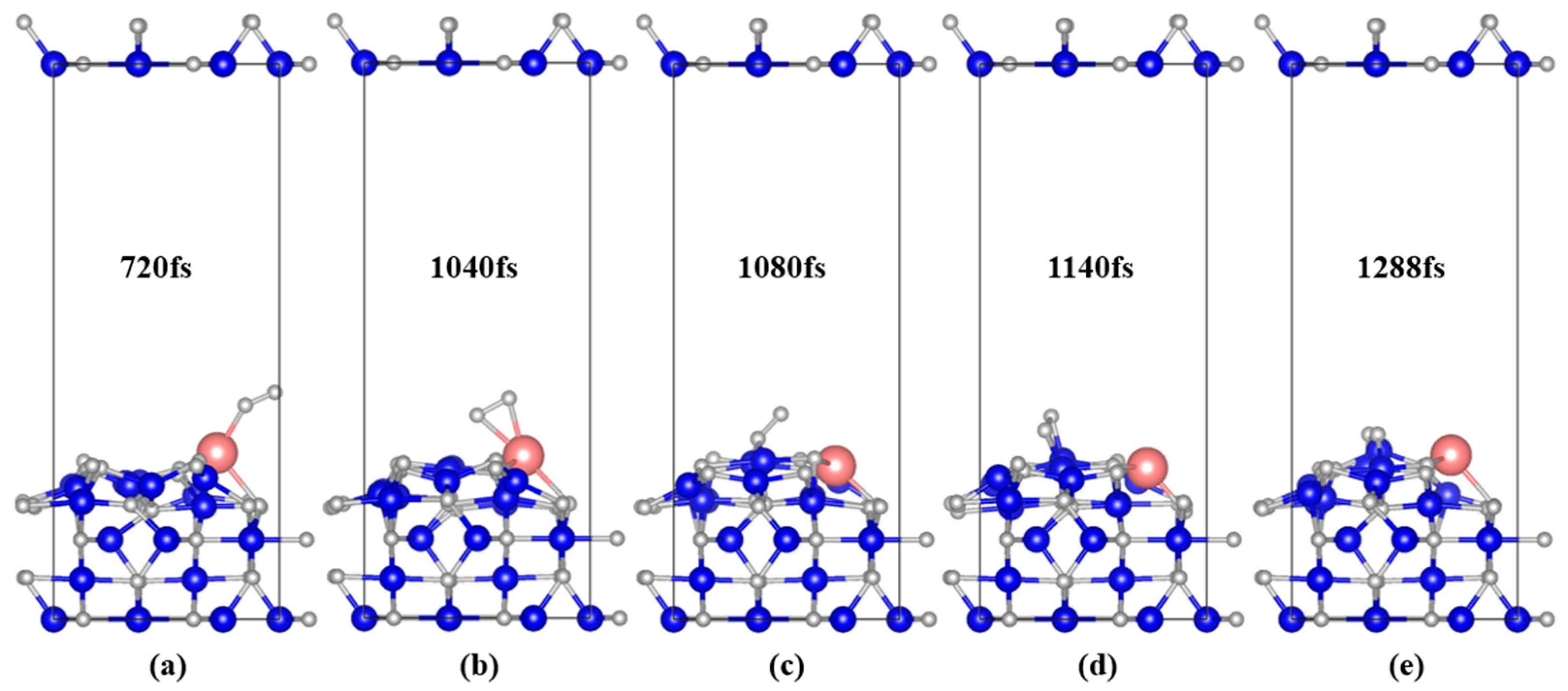

3.2.1. Geometric of System Structure Evolution

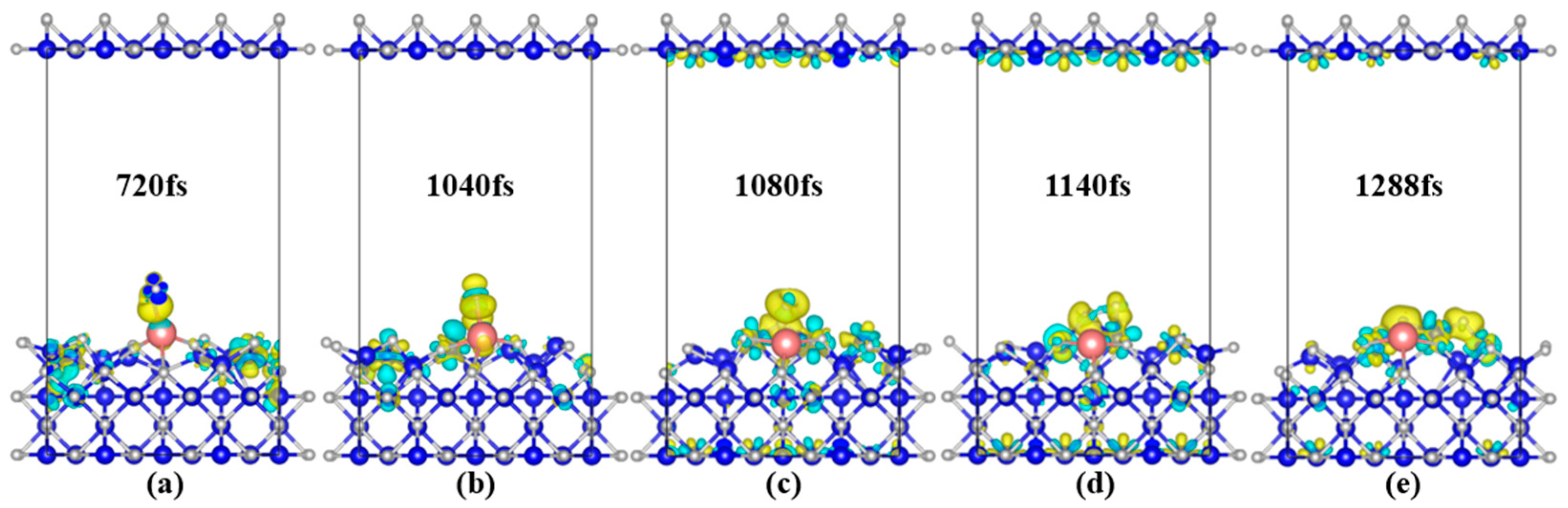

3.2.2. Evolution of System Electronic Structure

3.2.3. O–O Bond Length and System Energy Analysis

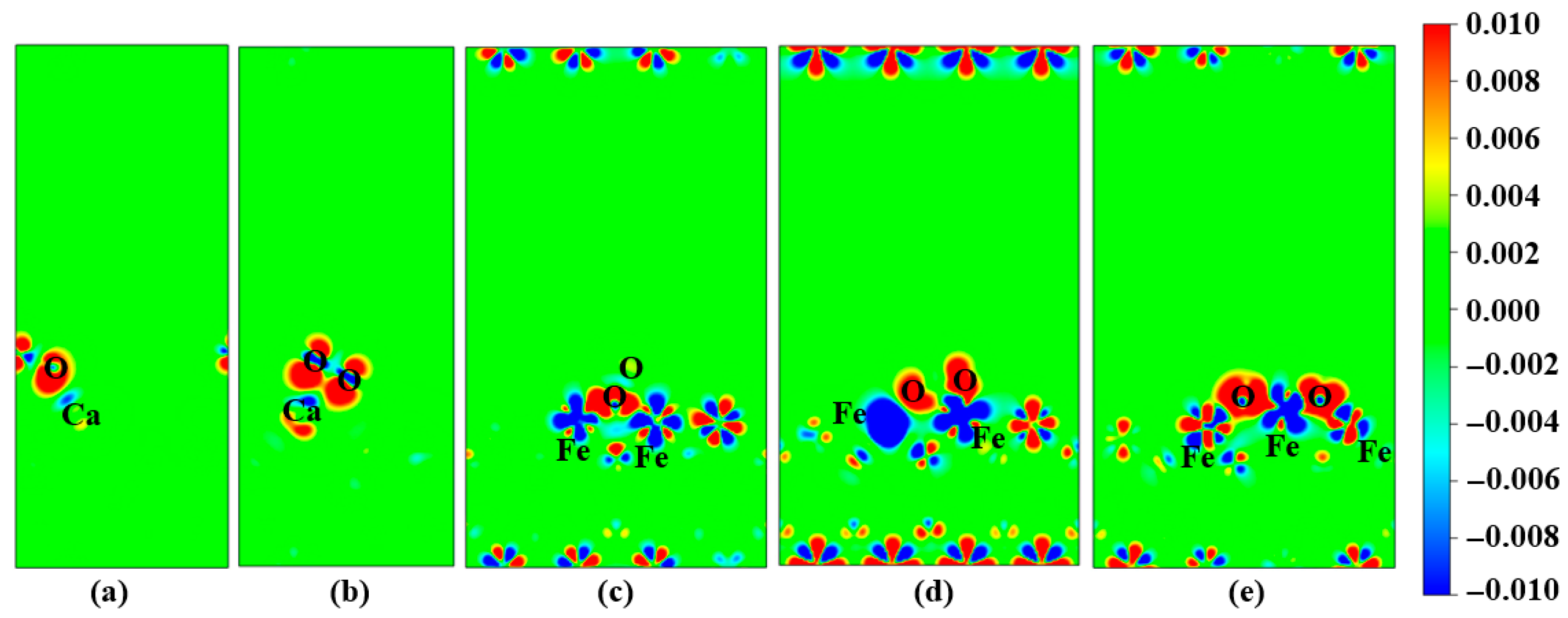

3.3. Segregation Behavior of Ca Atoms on Fe3O4 (110) Surface

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the presence of Ca, the adsorption-oxidation reaction on the surface proceeds along the following pathway: oxygen molecules first adsorb near Ca atomic sites; subsequently, O2 become activated under the influence of Ca atoms; then, O2 migrate to iron bridge sites; O–O bond broken occurs with the catalytic involvement of Fe atoms; finally, the dissociated O atoms stably occupy the Fe bridge sites.

- (2)

- During the adsorption-oxidation reaction, the breaking of the O–O bond is accompanied by a sharp decrease in system energy, indicating that the oxidation of Ca-doped Fe3O4 is an exothermic process. By the end of the reaction, the dissociated O atoms are positioned at the iron bridge sites, and the system energy stabilizes at approximately −509 eV.

- (3)

- Comparison with previous studies indicates that the Ca inhibits the oxidation of magnetite. Ca tends to segregate toward the Fe3O4 surface, and its inhibition mechanism primarily stems from the adsorption of O2 molecules, which retards O2 migration to active iron bridge sites, thereby impeding the dissociation process of O2 and ultimately slowing the overall oxidation kinetics of magnetite.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferrante, J. Applications of surface analysis and surface theory in tribology. Surf. Interface Anal. 1989, 14, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Blast furnace performance under varying pellet proportion. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2019, 72, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umadevi, T.; Kumar, P.; Lobo, N.F.; Prabhu, M.; Ranjan, M. Influence of pellet basicity (CaO/SiO2) on iron ore pellet properties and microstructure. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Liu, L.; Pan, Y.; Zuo, H.; Wang, J.; Xue, Q. A review: Research progress of flux pellets and their application in China. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2021, 48, 1048–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tian, S.; Long, F.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Gao, Q.; Shen, F. Experimental Investigation on the Strength of Fluxed Pellets Made by Medium-SiO2 Concentrate. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 30375–30385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Gan, M.; Jiang, T.; Yuan, L.S.; Chen, X.L. Influence of flux additives on iron ore oxidized pellets. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2010, 17, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, J.C. The Foundations of Magnetic Recording; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Geus, J.W. Preparation and properties of iron oxide and metallic iron catalysts. Appl. Catal. 1986, 25, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, X.; Long, Z.; He, S.; He, Y. Epoxy composites coating with Fe3O4 decorated graphene oxide: Modified bio-inspired surface chemistry, synergistic effect and improved anti-corrosion performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Li, W.; Wang, N.; Fu, G.; Chu, M.; Zhu, M. Influence and mechanism of CaO on the oxidation induration of Hongge vanadium titanomagnetite pellets. ISIJ Int. 2020, 60, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; He, Z. New insights on consolidation behavior of Fe2O3 in the Fe3O4-CaO-MgO-SiO2 system for fluxed pellet production: Phase transformations and morphology evolution. Miner. Eng. 2024, 214, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, G.; Murphy, S.; Berdunov, N.; Ceballos, S.F.; Shvets, I.V. Influence of Ca and K on the reconstruction of the Fe3O4 (001) surface. Surf. Sci. 2004, 564, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W. Nobel Lecture: Electronic structure of matter—Wave functions and density functionals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tkatchenko, A.; Scheffler, M. Modeling adsorption and reactions of organic molecules at metal surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3369–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.B.; Macdonald, D.D.; Gasem, Z.M. Density functional theory (DFT) as a powerful tool for designing new organic corrosion inhibitors. Part 1, an overview. Corros. Sci. 2015, 99, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Pu, D. First-principles investigation of oxidation behavior of Mo5SiB2. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 6698–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Song, Y.; Yang, R. Adsorption properties of oxygen atom on the surface of Ti2AlNb by first principles calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2017, 139, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhou, X.; Yu, J. The effect of surface structure on Ag atom adsorption over CuO(111) surfaces: A first principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 425, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Song, Y. First-principles investigation on stability and oxygen adsorption behavior of a O/B2 interface in Ti2AlNb alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 818, 152926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Wang, G.; Liu, Q.; Sui, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, Z. Investigation for oxidation mechanism of CrN: A combination of DFT and ab initio molecular dynamics study. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 885, 160940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, Q.; Niu, L.; Liu, Z. Oxidation Mechanism of Ti-Doped Fe3O4 (111): A Combined DFT and AIMD Study with an Experimental Verification. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2300132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep Kumar, T.K.; Viswanathan, N.N.; Ahmed, H.; Dahlin, A.; Andersson, C.; Bjorkman, B. Investigation of magnetite oxidation kinetics at the particle scale. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2019, 50, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Zuo, H.; Pan, Y.; Li, J. Investigation on Kinetic Mechanism and Oxidation Behavior of Magnesium High-Silicon Magnetite Pellets. JOM 2025, 77, 5259–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Jiang, H.; Lu, L.; Zhang, K.; Jiao, K.; Guo, F. Inhibition Behavior for the Oxidation of Si-Doped Fe3O4, A Combined Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics and Experimental Study. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Niu, L.; Liu, Z.J.; Jiang, H.Q. Inhibition Mechanism of MgO Addition on High-Temperature Oxidation of Magnetite: Density Functional Theory and Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Methods Joint Research and Experimental Verification. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2200887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, H.; Zheng, A.; Guo, F. O2 adsorption on Fe3O4 (110) surface and effect of gangue element Al doping: Combined study of binding experiment and ab initio molecular dynamics. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Tian, W.; Nepal, R.; Huq, A.; Nagler, S.; DiTusa, J.F.; Jin, R. Polyhedral distortions and unusual magnetic order in spinel FeMn2O4. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2330–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Giustetto, R.; Hoser, A. Structure of magnetite (Fe3O4) above the Curie temperature: A cation ordering study. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2012, 39, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Carballal, D.; Roldan, A.; Grau-Crespo, R.; de Leeuw, N.H. A DFT study of the structures, stabilities and redox behaviour of the major surfaces of magnetite Fe3O4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 21082–21097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.; Jia, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.X.; Bai, F.Q. Iron oxides with a reverse spinel structure: Impact of active sites on molecule adsorption. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2810–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, D.G. The chemical composition of spinels in the system Fe3O4 Mn3O4. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1969, 31, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E. The structure of magnetite: Symmetry of cubic spinels. J. Solid State Chem. 1986, 62, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Tong, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Meng, X.; Hu, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q. Octahedral/Tetrahedral Vacancies in Fe3O4 as K-Storage Sites: A Case of Anti-Spinel Structure Material Serving as High-Performance Anodes for PIBs. Small 2023, 19, 2301606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murnaghan, F.D. Finite deformations of an elastic solid. Am. J. Math. 1937, 59, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, F. Finite elastic strain of cubic crystals. Phys. Rev. 1947, 71, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, M.; Yu, Y. First principles studies of oxygen adsorption on the γ-U (1 1 0) surface and influences of Mo doping. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 179, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| K Point | System Energy (eV) | ∆E (eV) | Relative Energy (eV) | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 × 4 × 1 (benchmark) | −96.17981 | - | - | 141.979 |

| 5 × 5 × 1 | −96.17992 | 0.000116 | 7.9 × 10−6 | 155.135 |

| 6 × 6 × 1 | −96.17977 | −0.00015 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 369.698 |

| Simulation System | Adsorption Time | Bonding Time | O–O Bond Breakage Time | Stable Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetite [26] | 360 fs | 724 fs | 760 fs | 924 fs |

| Ca-magnetite | 720 fs | 1040 fs | 1140 fs | 1288 fs |

| Number of Layers | Surface | First Layer | The Second Layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| E0 (eV) | −477.895 | −476.58771 | −475.17152 |

| Eseg (eV) | - | 1.30734 | 2.72353 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, F.; Zhang, J. Mechanistic Insights into the Effect of Ca on the Oxidation Behavior of Fe3O4: A Combined DFT and AIMD Study. Metals 2025, 15, 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121321

Jiang H, Wang Y, Liu Z, Yang X, Guo F, Zhang J. Mechanistic Insights into the Effect of Ca on the Oxidation Behavior of Fe3O4: A Combined DFT and AIMD Study. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121321

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Huiqing, Yaozu Wang, Zhengjian Liu, Xin Yang, Fangyu Guo, and Jianliang Zhang. 2025. "Mechanistic Insights into the Effect of Ca on the Oxidation Behavior of Fe3O4: A Combined DFT and AIMD Study" Metals 15, no. 12: 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121321

APA StyleJiang, H., Wang, Y., Liu, Z., Yang, X., Guo, F., & Zhang, J. (2025). Mechanistic Insights into the Effect of Ca on the Oxidation Behavior of Fe3O4: A Combined DFT and AIMD Study. Metals, 15(12), 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121321