Tuning Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in Al-Zn-Mg Alloys: The Critical Role of Zn/Mg Ratio and Microstructure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

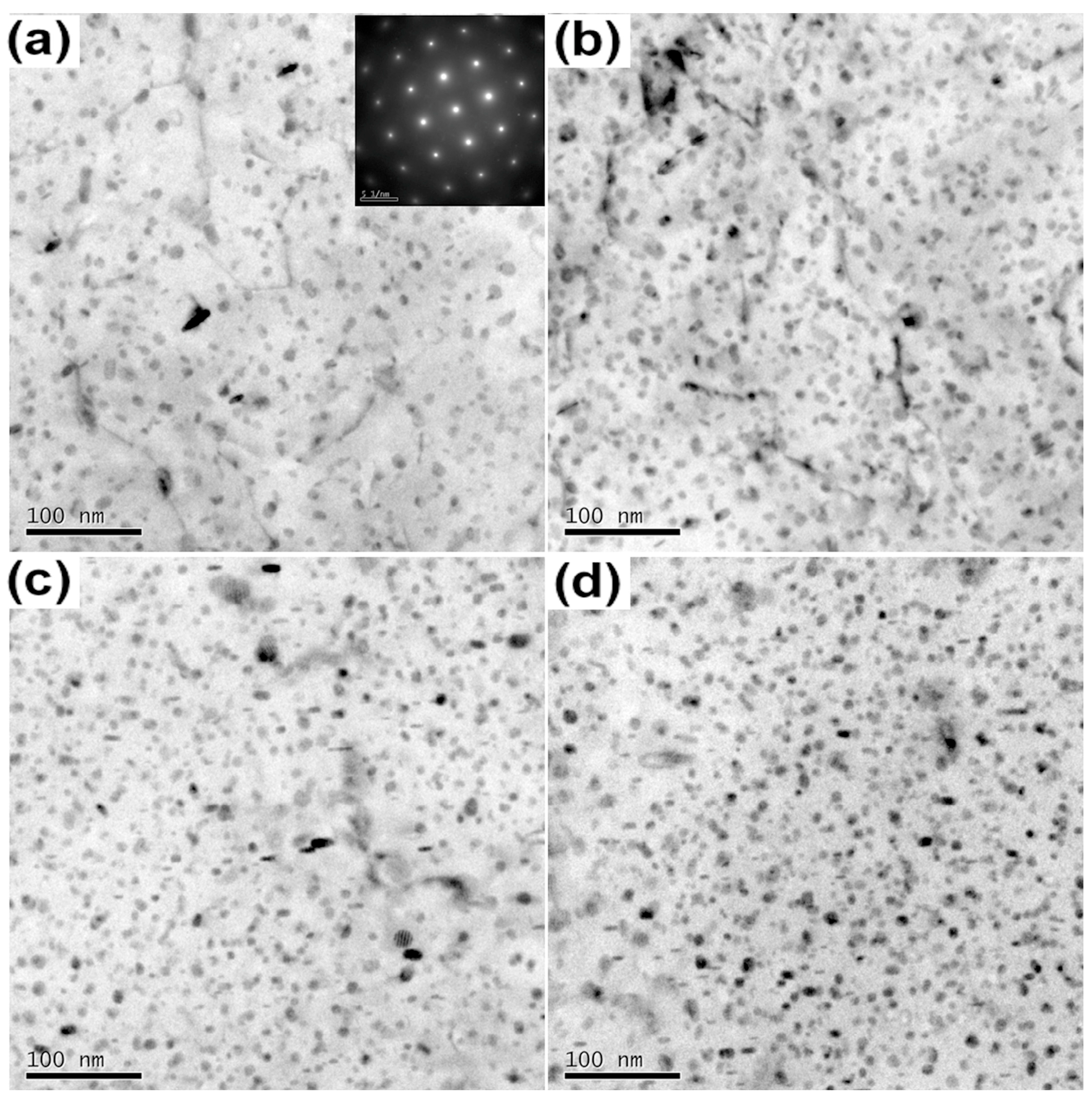

3.1. Microstructures

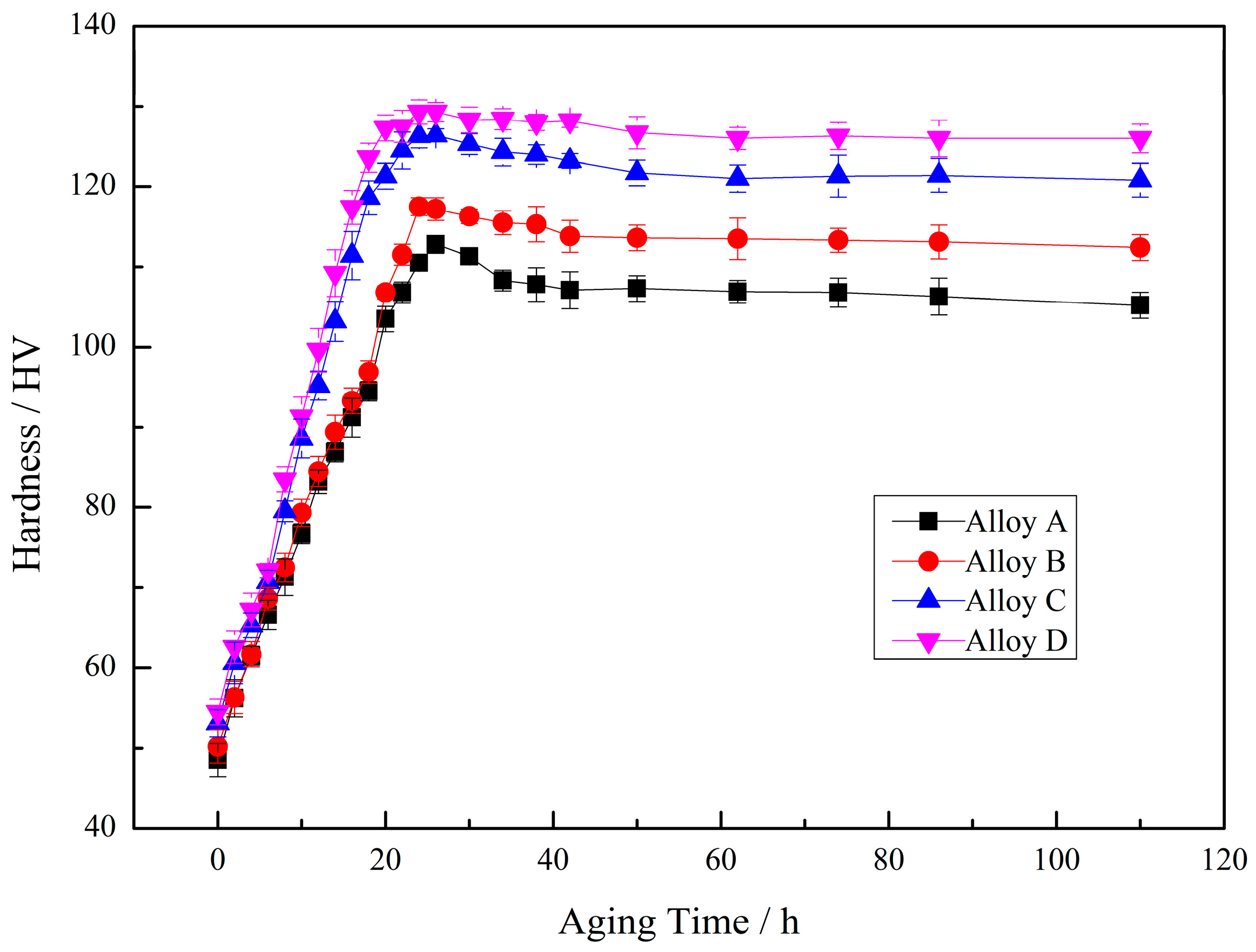

3.2. Mechanical Properties

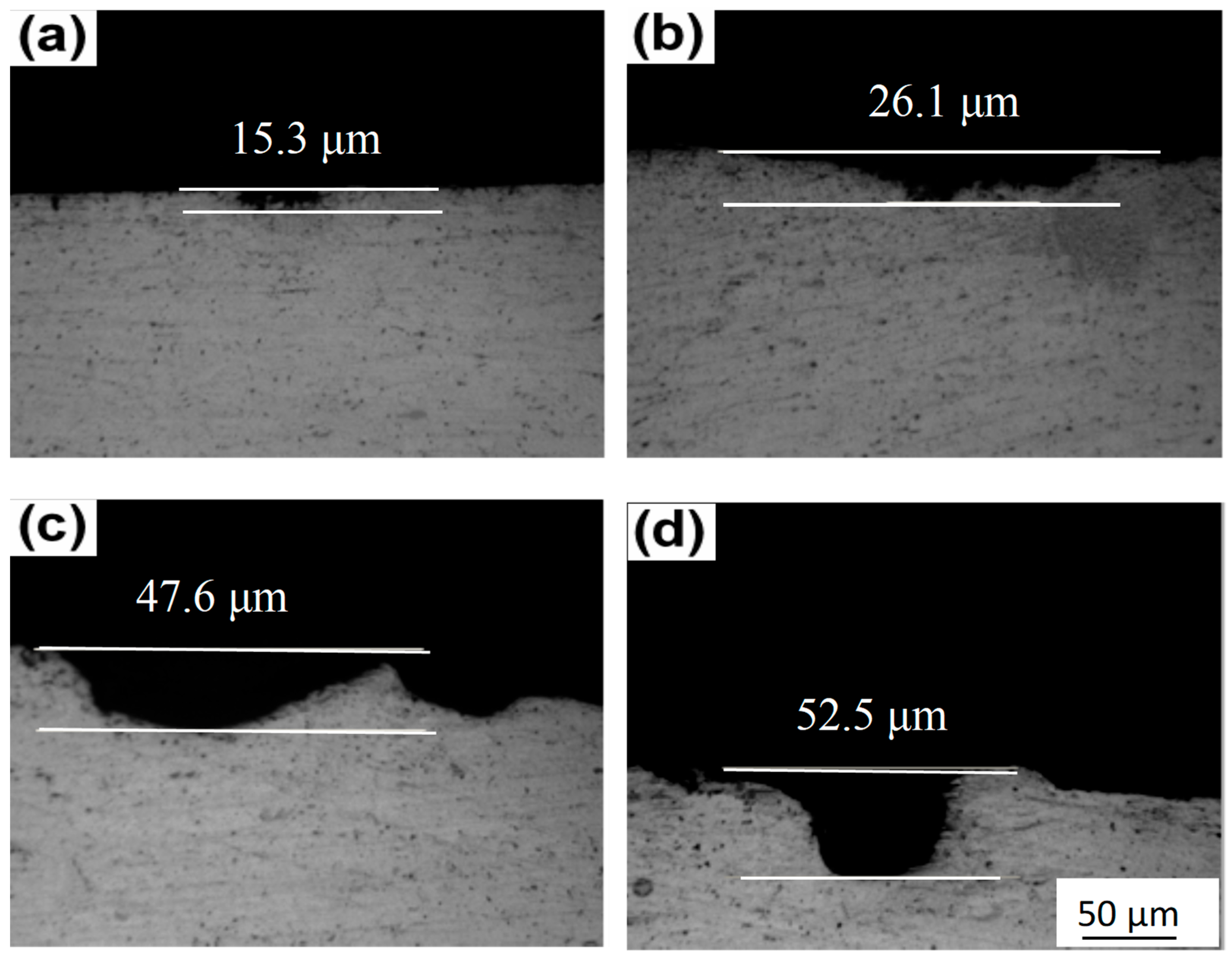

3.3. Corrosion Properties

3.4. SCC Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. The Microstructure–Strength Relationship

4.2. The Microstructure–Corrosion Performance Relationship

4.3. Microstructure-Dependent SCC Behavior

5. Conclusions

- The difference in yield strength among the four alloys with varying Zn/Mg ratios stems from the combined effects of grain boundaries and precipitates. The contribution of grain boundaries to yield strength first decreases and then increases with the rising Zn/Mg ratio. In contrast, the yield strength demonstrates a notable overall increase from 307 MPa to 342 MPa as the Zn/Mg ratio rises from 3.68 to 6.11. This trend indicates that precipitation strengthening, despite the varying grain boundary contribution, is the dominant factor influencing the yield strength.

- Grain boundary structures substantially influence intergranular corrosion resistance. A higher Zn/Mg ratio results in a narrower PFZ, which contributes positively to corrosion resistance. Conversely, this compositional shift promotes continuous precipitation at the grain boundary, adversely affecting corrosion performance. The highest Zn/Mg ratio of 6.11 exhibits the greatest corrosion depth, demonstrating that GBPs exert a more dominant influence on intergranular corrosion resistance than PFZ width.

- Higher Zn/Mg ratios exhibit notably finer grain boundary precipitates, which are unable to serve as effective hydrogen-trapping sites during stress corrosion. Consequently, these alloys demonstrate higher ISSRT values and poorer stress corrosion cracking resistance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, M.; Liu, S.; He, K.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J. Hydrogen-induced failure in a partially-recrystallized Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy with different aging conditions: Influence of deformation behavior dominated by microstructures. Mater. Des. 2023, 233, 112199. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Dong, H.; Shi, L.; Li, P.; Ye, F. Corrosion behavior and mechanical properties of Al-Zn-Mg aluminum alloy weld. Corros. Sci. 2017, 123, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Yang, M.J.; Chen, X.P.; Jin, Q.Q.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, Y.M. Precipitate evolution and properties of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy processed by thermomechanical treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 867, 144716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Pang, R.; Chen, H.; Ren, Y.; Tan, J. Optimization of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloys Through Multiple Remelting and Heat Treatment Cycles. Metals 2025, 15, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Xu, C.; Hamza, M.; Afifi, M.A.; Qaisrani, N.A.; Sun, H.; Wang, B.; Khan, W.Q.; Yasin, G.; Liao, W.B. Enhanced tensile strength in an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy via engineering the precipitates along the grain boundaries. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhang, M. Mechanism for enhanced precipitation strengthening due to the addition of copper to Al-Zn-Mg alloys with high Zn/Mg ratio. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Thronsen, E.C.; Hatzoglou, S.; Wenner, C.D.; Marioara, R.; Holmestad, B. Effect of cyclic ageing on the early-stage clustering in Al-Zn-Mg (-Cu) alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 846, 143280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L.K.; Gjønnes, J.; Hansen, V.; Li, X.Z.; Knutson-Wedel, M.; Waterloo, G.; Schryvers, D.; Wallenberg, L.R. GP-zones in Al-Zn-Mg alloys and their role in artificial aging. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfallah, A.; Raho, A.A.; Amzert, S.; Djemli, A. Precipitation kinetics of GP zones, metastable η′ phase and equilibrium η phase in Al-5.46wt%Zn-1.67wt%Mg alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Ye, L. Aging hardening and precipitation behavior of high Zn/Mg ratio Al-Zn-Mg alloys with and without Cu. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1022, 180017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.L.; Lee, R.S. Novel Aging Warm-Forming Process of Al-Zn-Mg Aluminum Alloy Sheets and Influence of Precipitate Characteristics on Warm Formability. Metals 2024, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, C.; Olivier, D.; Armel, D.M.; Jean, C.; Olivier, B.; Joel, A. Influence of Heat Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of a High-Strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr Alloy Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2023, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Effect of natural aging on quench-induced inhomogeneity of microstructure and hardness in high strength 7055 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 625, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Pan, Q.; Deng, Y.; Bin, X. Influence of Sc and Zr additions on microstructure and properties evolution of Al-Zn-Mg alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 2208–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Kai, X.; Xing, Y.; Bao, W.; Qian, W.; Zhao, Y. Effect of Sc and Zr co-microalloying on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of 7085Al alloy. Mater. Charac. 2025, 225, 115200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pan, W.; Fan, J.; Huang, X.; Shuai, L.; Godfrey, A.; Huang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X. Role of Sc/Zr in enhancement of η’ precipitation and control of microstructure evolution during selective laser melting of Al-Zn-Mg alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 243, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ma, X.; Xie, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of In Situ Electrical Pulse Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy Resistance Spot Welds. Metals 2025, 15, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Lu, F.; Zhou, S.; Liu, S.; Ye, L. Evolution of strengthening precipitates in Al-4.0Zn-1.8Mg-1.2Cu (at%) alloy with high Zn/Mg ratio during artificial aging. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jue, W.; Faguo, L. Research Status and Prospective Properties of the Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Series Aluminum Alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, S.Q.; Zhang, W.K.; Li, S.Q.; Liu Jizi, Z. Precipitation Thermodynamics in an Al-Zn-Mg Alloy with Different Grain Sizes. Metals 2024, 14, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Chen, S.; Chen, K.; Huang, L.; Chang, J.; Zhou, L.; Ding, Y. Correlations among stress corrosion cracking, grain-boundary microchemistry, and Zn content in high Zn-containing Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Chen, K.; Chen, S.; Huang, L.; Chen, G.; Chen, S. Effect of pre-strain and quench rate on stress corrosion cracking resistance of a low-Cu containing Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 833, 14237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, S.; Fu, L. Effects of quenching gents, two-step aging and microalloying on tensile properties and stress corrosion cracking of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 10198–10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldt, A.; Österreicher, J.A.; Schiffl, A.; Höppel, H.W. Optimizing the Zn and Mg contents of Al-Zn-Mg wrought alloys for high strength and industrial-scale extrudability. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 2972–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, S. Correlation between stress corrosion cracking resistance and grain boundary precipitations of a new generation high Zn containing 7056 aluminum alloy by non-isothermal aging and re-aging heat treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 850, 156711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, T. Recently-developed aluminium solutions for aerospace applications. Mater. Sci. Forum 2006, 519, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, L. Achieving superior strength and ductility in 7075 aluminum alloy through the design of multi-gradient nanostructure by ultrasonic surface rolling and aging. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 918, 165669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z. Effects of re-ageing treatment on microstructure and tensile properties of solution treated and cold-rolled Al-Cu-Mg alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 650, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, A.; Hc, A.; Ao, B. Quantified contribution of β′′ and β′ precipitates to the strengthening of an aged Al-Mg-Si alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 774, 138776. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, N. Hall-Petch relation and boundary strengthening. Scr. Metarialia 2004, 8, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, S.; He, K.; Zheng, X.; Jia, G. The effect of precipitate-free zone on mechanical properties in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu aluminum alloy: Strain-induced back stress strengthening. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 969, 172428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Wen, H.; Hu, T.; Topping, T.D.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Lavernia, E.J.; Schoenung, J.M. Mechanical behavior and strengthening mechanisms in ultrafine grain precipitation-strengthened aluminum alloy. Acta Mater. 2014, 62, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.A.; Easterling, K.E. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 185–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, P.; Qiao, S. Localized corrosion behavior associated with Al7Cu2Fe intermetallic in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 78, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, K.; Song, L. Influence of grain-boundary pre-precipitation and corrosion characteristics of inter-granular phases on corrosion behaviors of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2012, 177, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Q.; Li, H. Revealing the evolution of microstructure, mechanical property and corrosion behavior of 7A46 aluminum alloy with different ageing treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 792, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Hiroyuki, T.; Ryohei, M. Influence of hydrogen on strain localization and fracture behavior in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu aluminum alloys. Acta Mater. 2018, 159, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | Zn | Mg | Mn | Cu | Cr | Zr | Zn/Mg | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4.75 | 1.29 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 3.68 | Bal. |

| B | 4.67 | 1.13 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 4.13 | Bal. |

| C | 4.84 | 1.05 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 4.61 | Bal. |

| D | 5.68 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 6.11 | Bal. |

| Alloy | Test Environment | (Mpa) | (%) | ISSRT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 25 °C-Air | |||

| 25 °C-3.5% NaCl | ||||

| B | 25 °C-Air | |||

| 25 °C-3.5% NaCl | ||||

| C | 25 °C-Air | |||

| 25 °C-3.5% NaCl | ||||

| D | 25 °C-Air | |||

| 25 °C-3.5% NaCl |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, L.; Wu, J.; Ji, F.; Wan, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Tuning Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in Al-Zn-Mg Alloys: The Critical Role of Zn/Mg Ratio and Microstructure. Metals 2025, 15, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111211

Guan L, Wu J, Ji F, Wan Y, Fan L, Zhang X, Liu J. Tuning Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in Al-Zn-Mg Alloys: The Critical Role of Zn/Mg Ratio and Microstructure. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111211

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Liqun, Junchao Wu, Feifei Ji, Yingchun Wan, Lidan Fan, Xiaofang Zhang, and Jiahua Liu. 2025. "Tuning Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in Al-Zn-Mg Alloys: The Critical Role of Zn/Mg Ratio and Microstructure" Metals 15, no. 11: 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111211

APA StyleGuan, L., Wu, J., Ji, F., Wan, Y., Fan, L., Zhang, X., & Liu, J. (2025). Tuning Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in Al-Zn-Mg Alloys: The Critical Role of Zn/Mg Ratio and Microstructure. Metals, 15(11), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111211