Synthetic Rebalancing of Imbalanced Macro Etch Testing Data for Deep Learning Image Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

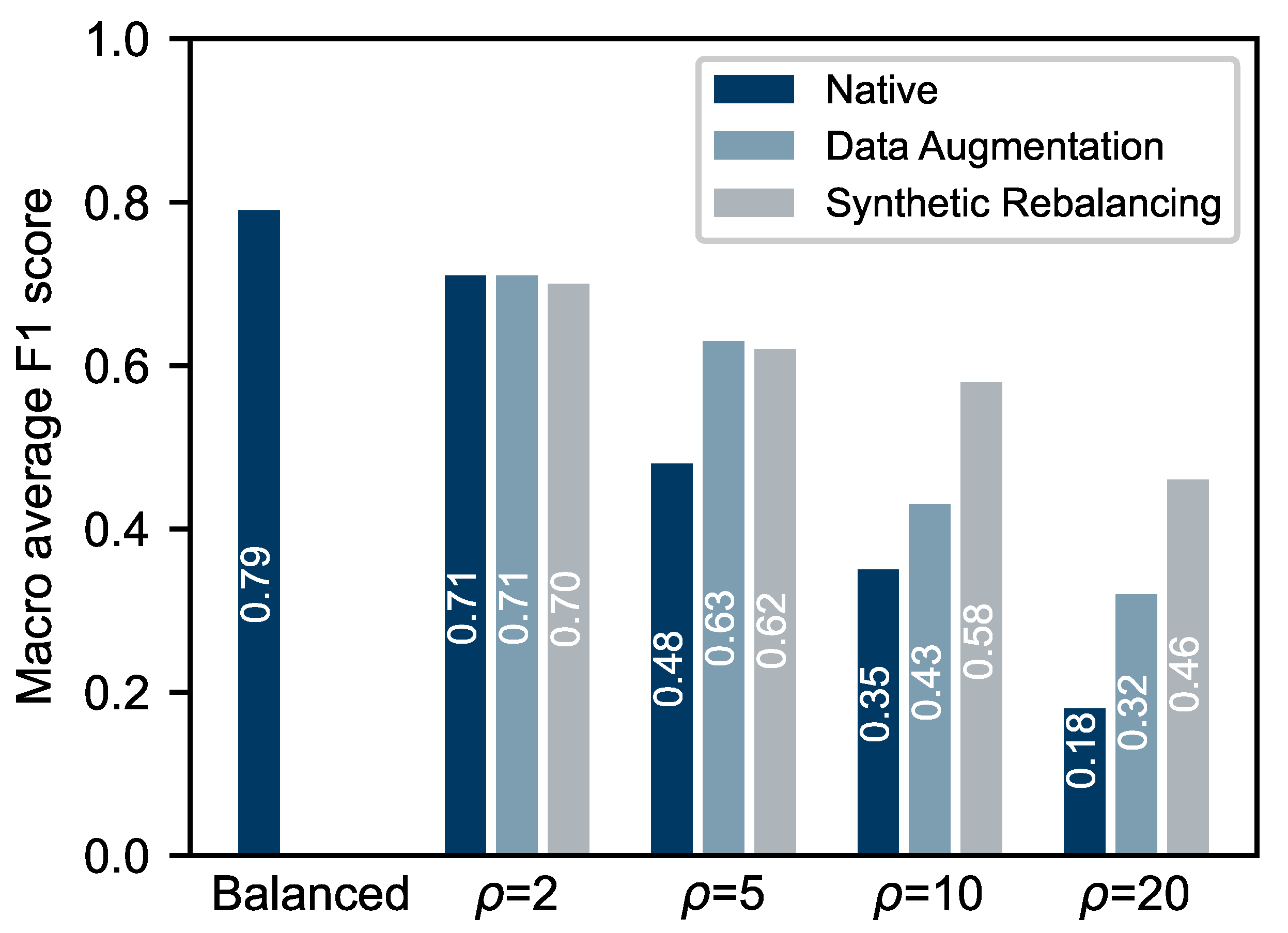

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

- Conform

- Light Etch Indication (LEI)

- Clean White Spot (CWS)

- Dirty White Spot (DWS)

- Non-Metallic Inlcusion (NMI)

2.2. Experimental Datasets

2.3. Deep Learning Image Classification Framework

2.4. Round Robin Test

2.5. Multiresolution Stochastic Texture Synthesis Framework

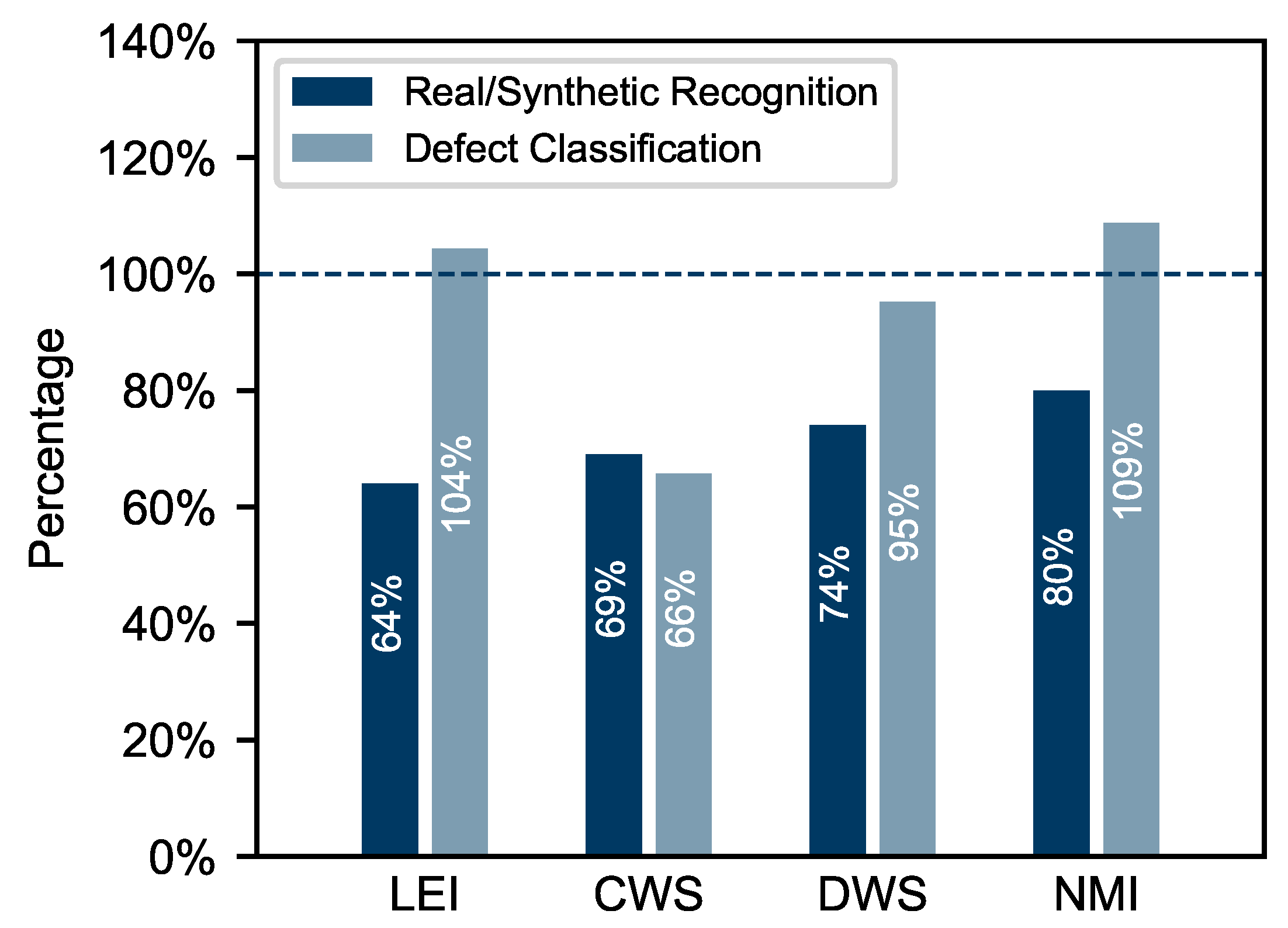

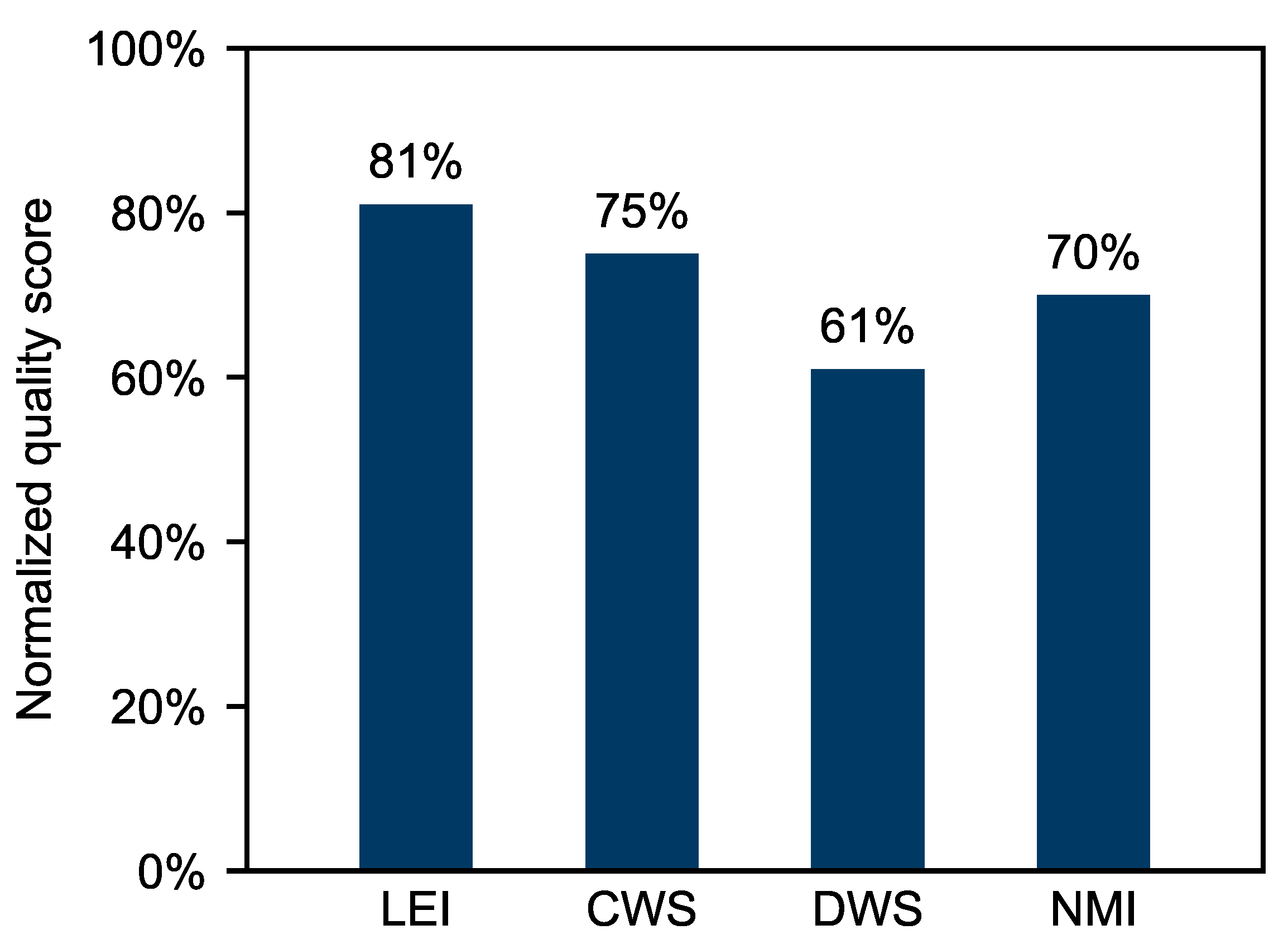

3. Results and Discussion

- Features of the inclusions particles such as unnatural shapes or unrealistic patterns.

- Periodic artificial structures, i.e., patterns in the matrix structure or stripes in the inclusions.

- Unnatural shape of the defect area.

- General artifacts.

- Grain boundaries missing or too weak.

- Boundary between matrix and defect area too sharp.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Image Selection

Appendix A.1. Conform

Appendix A.2. LEI

Appendix A.3. CWS

Appendix A.4. DWS

Appendix A.5. NMI

Appendix B. Class-Wise Metrics

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conform | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.77 |

| LEI | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.64 | |

| CWS | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.85 | |

| DWS | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| NMI | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.89 | |

| 2 | Conform | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| LEI | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.72 | |

| CWS | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.70 | |

| DWS | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.65 | |

| NMI | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.78 | |

| 5 | Conform | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.55 |

| LEI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| CWS | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.64 | |

| DWS | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.55 | |

| NMI | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.68 | |

| 10 | Conform | 0.30 | 0.95 | 0.45 |

| LEI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| CWS | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 | |

| DWS | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.34 | |

| NMI | 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.47 | |

| 20 | Conform | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.41 |

| LEI | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| CWS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| DWS | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.40 | |

| NMI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Conform | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.72 |

| LEI | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.51 | |

| CWS | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.67 | |

| DWS | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.83 | |

| NMI | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.83 | |

| 5 | Conform | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.64 |

| LEI | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.61 | |

| CWS | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.56 | |

| DWS | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.60 | |

| NMI | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | |

| 10 | Conform | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.48 |

| LEI | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.22 | |

| CWS | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.40 | |

| DWS | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.47 | |

| NMI | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.57 | |

| 20 | Conform | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.48 |

| LEI | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| CWS | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.49 | |

| DWS | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.15 | |

| NMI | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.38 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Conform | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.81 |

| LEI | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.46 | |

| CWS | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.70 | |

| DWS | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.73 | |

| NMI | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.81 | |

| 5 | Conform | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.63 |

| LEI | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.58 | |

| CWS | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | |

| DWS | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.53 | |

| NMI | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.63 | |

| 10 | Conform | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.69 |

| LEI | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.40 | |

| CWS | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | |

| DWS | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.47 | |

| NMI | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.70 | |

| 20 | Conform | 0.34 | 0.71 | 0.46 |

| LEI | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.27 | |

| CWS | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.59 | |

| DWS | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.33 | |

| NMI | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.64 |

References

- Taheri, H.; Gonzalez Bocanegra, M.; Taheri, M. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Smart Technologies for Nondestructive Evaluation. Sensors 2022, 22, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ramuhalli, P.; Jacob, R.E. Machine learning for ultrasonic nondestructive examination of welding defects: A systematic review. Ultrasonics 2023, 127, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzetto, M.; Teixeira, M.; Rodrigues, E.O.; Casanova, D. Deep learning models for visual inspection on Automotive Assembling Line. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020, 7, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, V.; Sizyakin, R.; Zhdanova, M.; Semenishchev, E.; Bezuglov, D.; Zelemskii, A. Automated visual inspection of fabric image using deep learning approach for defect detection. In Proceedings of the Automated Visual Inspection and Machine Vision IV, Online, 21–25 June 2021; Beyerer, J., Heizmann, M., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; He, J.; Yao, Z.; Bi, Q. Deep Learning and Machine Vision-Based Inspection of Rail Surface Defects. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 5005714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.M.; Britz, D.; Engstler, M.; Fritz, M.; Mücklich, F. Advanced Steel Microstructural Classification by Deep Learning Methods. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, A.R.; Potu, S.T.; Romich, D.; Möller, J.J.; Nützel, R. Microstructure quality control of steels using deep learning. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1222456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrfou, K.; Zhao, T.; Kordijazi, A. Deep Learning Methods for Microstructural Image Analysis: The State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2024, 13, 703–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azqadan, E.; Arami, A.; Jahed, H. From microstructure to mechanical properties: Image-based machine learning prediction for AZ80 magnesium alloy. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2025, 13, 4231–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, C.; Frazier, W.; Olsen, A.; Schwerdt, I.; McDonald, L.W.; Hagen, A. Improving microstructures segmentation via pretraining with synthetic data. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 249, 113639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.H.; Lee, S. A unified microstructure segmentation approach via human-in-the-loop machine learning. Acta Mater. 2023, 255, 119086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, F.; Stajduhar, I.; Canadija, M. Casting Defects Detection in Aluminum Alloys Using Deep Learning: A Classification Approach. Int. J. Met. 2023, 17, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leevy, J.L.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Bauder, R.A.; Seliya, N. A survey on addressing high-class imbalance in big data. J. Big Data 2018, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, M.; Lasota, T.; Trawiński, B.; Trawiński, K. Comparison of bagging, boosting and stacking ensembles applied to real estate appraisal. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Information and Database Systems: Second International Conference, ACIIDS, Hue City, Vietnam, 24–26 March 2010; Proceedings, Part II 2. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. Off. J. Int. Neural Netw. Soc. 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Shang, J.; Gu, M.; Huang, Y.; Gong, B. Learning from class-imbalanced data: Review of methods and applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 73, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasib, K.M.; Iqbal, M.S.; Shah, F.M.; Al Mahmud, J.; Popel, M.H.; Showrov, M.I.H.; Ahmed, S.; Rahman, O. A Survey of Methods for Managing the Classification and Solution of Data Imbalance Problem. J. Comput. Sci. 2020, 16, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, N.; Yan, L. Improved Faster RCNN Based on Feature Amplification and Oversampling Data Augmentation for Oriented Vehicle Detection in Aerial Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenkämper, D.; van Kevelaer, R.; Nattkemper, T.W. Strategies for Tackling the Class Imbalance Problem in Marine Image Classification. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Information Forensics, Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; Zhang, Z., Suter, D., Tian, Y., Branzan Albu, A., Sidère, N., Jair Escalante, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, U.; Shapiai, M.I.; Ismail, N.; Fauzi, H.; Salleh, S. Oversampling Based on Data Augmentation in Convolutional Neural Network for SiliconWafer Defect Classification. In Volume 327: Knowledge Innovation Through Intelligent Software Methodologies, Tools and Techniques; Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, D. Classification of imbalanced cloud image data using deep neural networks: Performance improvement through a data science competition. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Susan, S. Data Augmentation of Minority Class with Transfer Learning for Classification of Imbalanced Breast Cancer Dataset Using Inception-V3. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 July 2019; Morales, A., Fierrez, J., Sánchez, J.S., Ribeiro, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems—Volume 2, Cambridge, MA, USA, NIPS’14, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2014/file/f033ed80deb0234979a61f95710dbe25-Paper.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Bowles, C.; Chen, L.; Guerrero, R.; Bentley, P.; Gunn, R.N.; Hammers, A.; Dickie, D.A.; Hernández, M.V.; Wardlaw, J.M.; Rueckert, D. GAN Augmentation: Augmenting Training Data using Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.10863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; de Castro Aranha, C. Data Augmentation Using GANs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid-Adar, M.; Klang, E.; Amitai, M.; Goldberger, J.; Greenspan, H. Synthetic data augmentation using GAN for improved liver lesion classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Khan, S.; Harouni, M.; Abbasi, R.; Iqbal, S.; Mehmood, Z. Brain tumor segmentation using K-means clustering and deep learning with synthetic data augmentation for classification. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2021, 84, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukreja, V.; Kumar, D.; Kaur, A.; Geetanjali; Sakshi. GAN-based synthetic data augmentation for increased CNN performance in Vehicle Number Plate Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 5–7 November 2020; pp. 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Roy, S.; Nguyen, Y.T.; Choi, J.B.; Udaykumar, H.S.; Baek, S.S. Deep learning for synthetic microstructure generation in a materials-by-design framework for heterogeneous energetic materials. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokina, D.; Muravleva, E.; Ovchinnikov, G.; Oseledets, I. Microstructure synthesis using style-based generative adversarial networks. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 043308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Goo, N.H.; Park, W.B.; Pyo, M.; Sohn, K.S. Virtual microstructure design for steels using generative adversarial networks. Eng. Rep. 2021, 3, e12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambard, G.; Yamazaki, K.; Demura, M. Generation of highly realistic microstructural images of alloys from limited data with a style-based generative adversarial network. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, T.; Trampert, P.; Boughorbel, F.; Sprenger, J.; Klusch, M.; Fischer, K.; Kübel, C.; Slusallek, P. Digital reality: A model-based approach to supervised learning from synthetic data. AI Perspect. 2019, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampert, P.; Rubinstein, D.; Boughorbel, F.; Schlinkmann, C.; Luschkova, M.; Slusallek, P.; Dahmen, T.; Sandfeld, S. Deep Neural Networks for Analysis of Microscopy Images—Synthetic Data Generation and Adaptive Sampling. Crystals 2021, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efros, A.; Leung, T. Texture synthesis by non-parametric sampling. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Corfu, Greece, 20–27 September 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.Y.; Levoy, M. Fast texture synthesis using tree-structured vector quantization. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, ‘SIGGRAPH ’00, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–28 July 2000; pp. 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikhmin, M. Synthesizing natural textures. In Proceedings of the 2001 Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics, I3D ’01, New York, NY, USA, 26–29 March 2001; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.F. Image Texture Tools. Ph.D. Thesis, Clayton School of Information Technology, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, P.; Luschkova, M.; Cordier, A.; Shukor, M.; Schappert, M.; Dahmen, T. Synthetic training data generation for deep learning based quality inspection. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Quality Control by Artificial Vision, Tokushima, Japan, 12–14 May 2021; Komuro, T., Shimizu, T., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 11794, p. 1179403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.R. (Ed.) ASM Specialty Handbook: Heat-Resistant Materials; ASM International: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, D. (Eds.) Aerospace Materials Handbook, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. Melting Processes and Solidification in Alloys 718-625. In Proceedings of the Superalloys 718, 625 and Various Derivatives, Warrendale, PA, USA, 23–26 June 1991; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J.M.; Jackman, L.A.; Adasczik, C.B.; Davis, R.M.; Forbes-Jones, R. Advances in Triple Melting Superalloys 718, 706, and 720. In Proceedings of the Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivatives, Pittsburgh, PA, USA,, 27–29 June 1994; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, L.A.; Maurer, G.E.; Widge, S. White Spots in Superalloys. In Proceedings of the Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivatives, Warrendale, PA, USA, 26–29 June 1994; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Damkroger, B.; Kelley, J.B.; Schlienger, M.E.; Avyle, J.A.; Williamson, R.L.; Zanner, F.J. The influence of VAR processes and parameters on white spot formation in Alloy 718. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivatives, Warrendale, PA, USA, 26–29 June 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Paulonis, D.F.; Oblak, J.M.; Duvall, D.S. Precipitation in nickel-base alloy 718. ASM (Amer. Soc. Met.) Trans. Quart. 1969, 62, 611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Azadian, S.; Wei, L.Y.; Warren, R. Delta phase precipitation in Inconel 718. Mater. Charact. 2004, 53, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Chen, W.P.; Wang, T.W. A diffraction study of the γ′′ phase in INCONEL 718 superalloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. 2001, 32, 1887–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararaman, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, S. Precipitation of the δ-Ni3Nb phase in two nickel base superalloys. Metall. Trans. A 1988, 19, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, M.J.; Knorovsky, G.A.; Headley, T.J.; Romig, J. The Solidification Metallurgy of Alloy 718 and Other Nb-Containing Superalloys. In Proceedings of the Superalloy 718, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 12–14 June 1989; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.f.; Yang, S.l.; Qu, J.l.; Du, J.h.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, N. Inclusions in wrought superalloys: A review. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2021, 28, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. (IJCV) 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, K.A. Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2012, 8, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11966–11976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Radosavovic, I.; Kosaraju, R.P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Designing Network Design Spaces. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10425–10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Fedus, W.; Du, X.; Cubuk, E.D.; Srinivas, A.; Lin, T.Y.; Shlens, J.; Zoph, B. Revisiting ResNets: Improved training and scaling strategies. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’21, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Curran Associates Inc.: Nice, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity Mappings in Deep Residual Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE Computer Society, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-Reference Image Quality Assessment in the Spatial Domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatanath, N.; Praneeth, D.; Maruthi Chandrasekhar, B.; Channappayya, S.S.; Medasani, S.S. Blind image quality evaluation using perception based features. In Proceedings of the 2015 Twenty First National Conference on Communications (NCC), Maharashtra, India, 27 February–1 March 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurka, G.; Dance, C.; Fan, L.; Willamowski, J.; Bray, C. Visual categorization with bags of keypoints. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Statistical Learning in Computer Vision, ECCV, Prague, Czech Republic, 11–14 May 2004; Volume 1, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

| Classes | Number of Samples |

|---|---|

| Conform | 140 |

| LEI | 351 |

| CWS | 209 |

| DWS | 106 |

| NMI | 110 |

| Sum | 916 |

| Samples per Defect Class | Samples in Conform Class | Total Samples in the Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Balanced) | 85 | 85 | 425 |

| 2 | 42 | 85 | 253 |

| 5 | 17 | 85 | 153 |

| 10 | 8 | 85 | 117 |

| 20 | 4 | 85 | 101 |

| Real Samples per Defect Class | Synthetic Samples per Defect Class | Samples in Conform Class | Total Samples in the Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 42 | 43 | 85 | 425 |

| 5 | 17 | 68 | 85 | 425 |

| 10 | 8 | 77 | 85 | 425 |

| 20 | 4 | 81 | 85 | 425 |

| Model | Cross-Validation Accuracy | Model Architecture Source |

|---|---|---|

| ConvNextBase | 0.72 | [59] |

| DenseNet121 | 0.70 | [58] |

| DenseNet169 | 0.75 | [58] |

| DenseNet201 | 0.74 | [58] |

| EfficientNetV2B3 | 0.68 | [60] |

| EfficientNetV2L | 0.67 | [60] |

| InceptionV3 | 0.62 | [56] |

| RegNetX120 | 0.71 | [61] |

| RegNetY080 | 0.71 | [61] |

| RegNetY120 | 0.73 | [61] |

| RegNetY160 | 0.70 | [61] |

| ResNetRS200 | 0.63 | [62] |

| ResNetV2101 | 0.69 | [63] |

| VGG19 | 0.69 | [64] |

| Xception | 0.68 | [65] |

| Question | Observed Agreement | Expected Agreement | Fleiss’ Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| real/synthetic recognition | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.42 |

| defect classification | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Class | Standard Deviation | Real Control Samples Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| LEI | 0.803 | 0.765 |

| CWS | 1.001 | 0.930 |

| DWS | 0.740 | 0.673 |

| NMI | 0.737 | 0.533 |

| Classes | Test Set F1 Score |

|---|---|

| Conform | 0.83 |

| LEI | 0.57 |

| CWS | 0.76 |

| DWS | 0.74 |

| NMI | 0.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schöbel, Y.N.; Müller, M.; Mücklich, F. Synthetic Rebalancing of Imbalanced Macro Etch Testing Data for Deep Learning Image Classification. Metals 2025, 15, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111172

Schöbel YN, Müller M, Mücklich F. Synthetic Rebalancing of Imbalanced Macro Etch Testing Data for Deep Learning Image Classification. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111172

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchöbel, Yann Niklas, Martin Müller, and Frank Mücklich. 2025. "Synthetic Rebalancing of Imbalanced Macro Etch Testing Data for Deep Learning Image Classification" Metals 15, no. 11: 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111172

APA StyleSchöbel, Y. N., Müller, M., & Mücklich, F. (2025). Synthetic Rebalancing of Imbalanced Macro Etch Testing Data for Deep Learning Image Classification. Metals, 15(11), 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111172