Abstract

Electoral ergonomics pertains to the interface between electoral psychology and electoral design. It moves beyond traditional models of electoral organisation that often focus on mechanical effects or changes to who actually votes to investigate the ways in which different forms of electoral organisation will switch on and off various electoral psychology buttons (in terms of personality, memory, emotions and identity) so that the very same person’s electoral experience, thinking process, and ultimately electoral behaviour will change based on the design of electoral processes. This article illustrated this phenomenon based on two case studies, one which showed that young people seemed more likely to vote for radical right parties if they voted postally than in person at the polling station based on panel study evidence from the UK, and another which showed that the time citizens deliberate about their vote varied from 1 to 3 depending on whether they were asked to vote using materialised or dematerialised mono-papers or poly-paper ballots. The article suggested that electoral ergonomics, as the interface between electoral psychology and election design, exceeded the sum of its parts.

1. Introduction

At a time when several electoral outcomes have shocked societies has led electoral science to renew our understanding of the psychology of voters. From the victories of Brexit and Donald Trump in 2016 to the earthquake to the French party system since the 2017 French Presidential election, and the succession of elections unable to deliver parliamentary majorities in Spain, Israel and the UK in recent years, there has been a sense that most contemporary avenues of electoral investigation—be they sociological, economic or even contextual are not explaining the full picture of electoral behaviours that few would have predicted even a few years ago. This effort to refresh our models of electoral psychology are most necessary and valuable, but in this article, we suggested that to fully capture those effects, we also need to understand the interface between voters’ psychology and the quasi-infinite variations in electoral organisation and arrangements, which may trigger different psychological reactions even when they have been assumed to be neutral by institutional designer. This is the foundation of the concept of electoral ergonomics.

The impact of electoral arrangements on politics has long interested the political science literature. Possibly the most famous example in the history of the discipline stems from the work of Duverger [1] who established that the choice of majoritarian or proportional electoral systems would, respectively, lead to two and multi-party systems. When considering this finding decades later, there are two striking elements to note. First, the effect of an institutional choice (electoral arrangements) on an institutional reality (the party system) is, in fact, mediated by behavioural effects. In other words, electoral systems create the party systems they do because the electoral system constrains the way in which citizens ultimately vote. Second, even at the time, Duverger [1] distinguished between a “mechanical” effect leading to the emergence of two-party systems and a “psychological” effect resulting in a multiparty system. The modern reading of the work often uses those as shortcuts for “well-evidenced” and “not so well evidenced” claims, but what if we took them at face value? What if indeed, electoral arrangements affected political behaviour not so much because of the institutional formatting that they directly impose but rather because of the way they are in interface with citizens’ psychology, triggering different types of personality traits, memories, emotions and aspects of electoral identity?

Ergonomics is a central concept in the fields of design, architecture and marketing. It encompasses ‘the interactions among human and other elements of a system’ with an aim ‘to optimise human well-being and overall system performance’ [2]. However, Bruter and Harrison [3,4] note that this apparently straightforward definition makes a critical assumption and is not simply concerned with adapting design elements to human beings but rather adapting those design elements to human beings given their function. In other words, if one were to design a hat that perfectly fits the shape of a human head, it would unlikely be shaped like a mask or a beanie. However, the fact that its function is to protect us from the rain and the sun means that instead, it has to have a sizeable brim. Consequently, they define electoral ergonomics as “the interface between electoral arrangements and voters’ psychology” and claim that it has to be analysed based on functions that given elections can have in the perceptions of voters, and which may vary by country, type of election, individual and context.

Critically, thinking in terms of electoral ergonomics (i.e., an interface between design and psychology) rather than electoral arrangements alone means that a number of design elements which should logically be effect-neutral in mechanical terms may have ergonomic effect on citizens’ vote because whilst seemingly mechanically irrelevant, they may affect the atmosphere of the vote, the experience of the voter, his/her interactions with the system and with others and trigger different memories, emotions or broadly defined psychological reactions.

In this article, we thus empirically investigated the claim that supposedly affects neutral design choices indeed have effects on citizens’ electoral experience and behaviour, focusing on two case studies: postal voting and extremist voting, paper design and electoral deliberation and decision time.

2. Theoretical Framing: Mechanical and Psychological Effects of Electoral Arrangements and Ergonomics

It has long been accepted by political scientists that electoral design can have an impact on election results. The majority of the models investigating those relationships take a highly institutionalist perspective, in other words, focus on system designers’ ability to (sometimes unethically) distort electoral outcomes by making it easier or harder for some parties to achieve representation, modify the pool of voters who will participate in an election or influence the way in which the votes are aggregated and translated into seats to the relative advantage (or disadvantage) of some political actors.

We have already alluded to the work of Duverger [1] who found that electoral system choices will affect the number of political parties able to coexist within a party system. His research is echoed by the findings of Lipset and Rokkan [5] and the four thresholds which they see as responsible for setting the effective size of a party system. Whilst those two studies pertain to potentially involuntary effects of system design on political outcomes, other authors turn openly to the way in which those in control of system design can use electoral laws to achieve specific outcomes, favouring—or on the contrary—inhibiting the success of given political forces. This is the ambition of the seminal work of Grofman and Lijphart [6] and also of more specific elements, such as malapportionment (inequity in representation between various districts) and gerrymandering (the attempt to design electoral districts in such a way as to optimise districts with small but safe majorities for a preferred party whilst making opposed parties “waste” their electoral advantage by allocating districts where they can expect to benefit from needlessly large majorities and others where they will benefit from large but insufficient minorities). This is reflected in the works of Schubert [7], Erikson [8], Ansolabehere and Snyder [9], Grofman [10] and many more. Ultimately, this body of literature has also assessed electoral arrangements normatively under the prisms of electoral integrity [11,12] and the success of democratic transition [13].

Beyond the ‘obvious’ case of electoral system design, several authors have also explored increasingly more peripheral elements of electoral arrangements. They have notably considered the impact of convenience voting on turnout [14,15] on its own or combined with additional treatments [16]. With exceptions focusing on voters for whom traditional voting may be particularly onerous, such as those who live far away from polling places [17] and voters with disabilities [18], the literature has found those effects on turnout very limited. This is because those using convenience voting options typically tend to be highly motivated voters [12] who would participate anyway. In turn, this results in limited differences in profile between early and Election Day voters [19,20]. In turn, convenience voting does not seem to lead to the increase in left-wing (for instance in the US Democrat) voters that many scholars expected given the imbalanced sociological and ideological profile of abstentionists [20,21,22].

A particular sub-component of “convenience voting” studies, which has attracted a lot of attention, are postal and remote e-voting. Those include the works of [12,23,24,25]. Once again, however, the focus is predominantly either on participation or on safety and how remote e-voting, in particular, maybe more prone than other voting modes to error.

In the examples above, political scientists focused on the effects of electoral arrangements on who votes and how their votes are counted rather than any expectation that changes to the electoral design would affect the way a given individual votes. This differs from a final example of existing research regarding the impact of where people vote, i.e., the choice of location of polling stations. Several scholars have indeed looked at the impact of hosting polling stations in churches or schools in the US. This time, there is no suggestion about the voting organisation bringing different people to the polling station but rather, instead, a suggestion that the location of polling station will affect people’s choice everything else being equal, with suggestions that voting in a school makes people more likely to spend public spending on education and more likely to support Democrats compared to voting in a church [26].

3. Two Case Studies of Electoral Ergonomic Effects

In this article, the two examples that we analysed corresponded to a similar assumption: not cases where different models of electoral organisations would lead different people to vote with profiles that could modify electoral outcomes as a result, but rather situations where we could control—either using panel study or experimental controls—that it is the electoral organisation itself, which results in a changed electoral experience and behaviour for a given citizen.

In the first case study, we considered the impact of voting postally on the likelihood of citizens casting their vote for a radical right party using panel study surveys during an actual General Election in the UK. Explicitly, our model suggested that people would behave differently when they vote in the solemn and public context of a polling station as opposed to the private and informal context of their own home. Our theoretical expectations were that given that research showed that visiting a polling station made citizens feel sociotropic, think of the way others vote, and try to embrace what they subconsciously see as their responsibility as voters (their “electoral identity”) as opposed to just expressing a direct preference as they vote [3], and visiting a polling station would generally lower citizens’ tendency to support radical parties. We also expected young people to be the most exposed to such effects as their electoral habituation is not fully settled [27,28]. As a result, our hypothesis was that young people would be less likely to support radical parties if they vote at a polling station rather than from home.

The second case study pertained to the time citizens will think about their vote when they cast a paper or electronic ballot. This time, our main theory was based on existing literature on materialised and dematerialised reactions [29,30], notably in surveys, which suggested that human beings naturally provide more attention to materialised prompts than to dematerialised ones. As a result, we expected people who vote using paper ballots to typically spend more time deliberating about their vote than those using Direct Recording Electronic voting machines.

4. Data and Methods

The two case studies are based on separate bodies of data

4.1. First Case Study: Survey of British Citizens in the 2010 General Election

The first was based on an original panel study survey, which took place during the 2010 UK General Election, with a first wave conducted three weeks before the vote and the second one on election night. The study was conducted using a fully representative sample of 2020 respondents selected using quota sampling in wave 1. A total of 1953 of them answered the second wave of the survey on Election Night. The survey was conducted online. The vote for the extreme right was measured by totalling those people who declared voting for the BNP, UKIP and the English Democrats in wave 2. To control for self-selection effects, we compared those results to differences in answer to a propensity to vote questions for the same three parties in wave 1.

4.2. Second Case Study: A Visual Lab Experiment in Germany

The second case study was based on a visual experiment conducted in Germany. The visual experiment enabled us to calculate the exact length of time between when citizens discovered the ballot paper (be it material or electronic) and the moment when they actually cast their vote. The experiment was conducted in partnership with the Falling Walls conference in Berlin in 2012. In total, 145 people participated in the experiment and voted using three different ballot types: 71 using a Direct Recording Electronic voting ballot based on a computer, 37 using a UK type single ballot with names listed and a requirement to put a cross in the box of the candidate of their choice and 37 using French type ballots (pre-printed individual ballots for each candidate with the voter asked to select one and put it in the envelope provided without any instruction). Participants were recruited from the conference participants during the coffee breaks. The visual experiment was conducted in ways that kept the nature of the citizens’ vote invisible at all times though with clear views of when they actually started filling their ballot (the time point we used as the measure of the completed electoral deliberation) using a camera and a protective screen, which meant that only the shadow of voters was visible at all times and not their actual face or ballot. A similar experiment was run in 2019 in the UK using a predominantly student sample and led to similar results.

5. Analysis

5.1. Case Study No. 1: Young People Are More Likely to Support a Radical Right Party If They Vote Remotely than in a Polling Station

Since 2001, any British citizen is able to request a postal ballot without being required to provide any reason except in Northern Ireland. After a bold experiment of conducting the 2004 General Elections using all-postal voting in some of the constituencies, the proportion of citizens voting postally has generally increased slowly but consistently during the period, reaching 15.3% of the electorate in the 2010 General Elections, 16.4% in 2015 and 18% in 2017 [31]. This is a significantly lower proportion and slower growth than in the US, for instance, where advance and absentee voting represented 36.6% of total voters in 2016 despite requiring justification in a significant minority of states.

Postal voting has generational implications for two main reasons. Young voters are ostensibly the main target of the policy under a “convenience vote” logic, but older voters are those making the greatest use of the policy due to health and mobility issues. [32,33] also showed that, in practice, young voters very significantly preferred voting in a polling station if they could and derived far more positive emotions and impressions when they did compare to voting from home (though their study used internet rather than postal voting as comparator).

Young people can also be a prime target due to their mobility. The Electoral Commission estimates that about a third of young people are not or incorrectly registered, a figure that echoes the findings of [3], who suggested, however, that misregistration increased as deregistration decreased and that misregistration is, in fact, still underestimated. Young people are particularly mobile, often having several addresses (for instance, a place where they study and another where their parents live, or a place where they study and another when they move for their first job). In the UK, citizens are technically allowed to register in multiple places as long as they only vote once, but many are not aware of that or simply do not do it, and for many young people, postal voting may not be an effective option in such cases (because they still need to be able to receive their mailed ballot, which may arrive in a place where they may not be). Consequently, whilst older citizens may be less able to vote in person at a polling station but more likely than most to vote postally, young people may be less able than average to vote both at their designated polling station and by mail (whilst they would conversely be more likely than average to be able to vote in any available polling station). This is particularly true when votes take place during university holidays, which was the case for the 2016 EU membership referendum or the 2017 General Elections. In any case, we know that young people are less likely than other generations to opt for postal voting by choice because notwithstanding how it may reduce the cost of voting, from their point of view, it even more significantly reduces the benefits of voting in terms of excitement, happiness, and sense of collective integration [3,4,32,33].

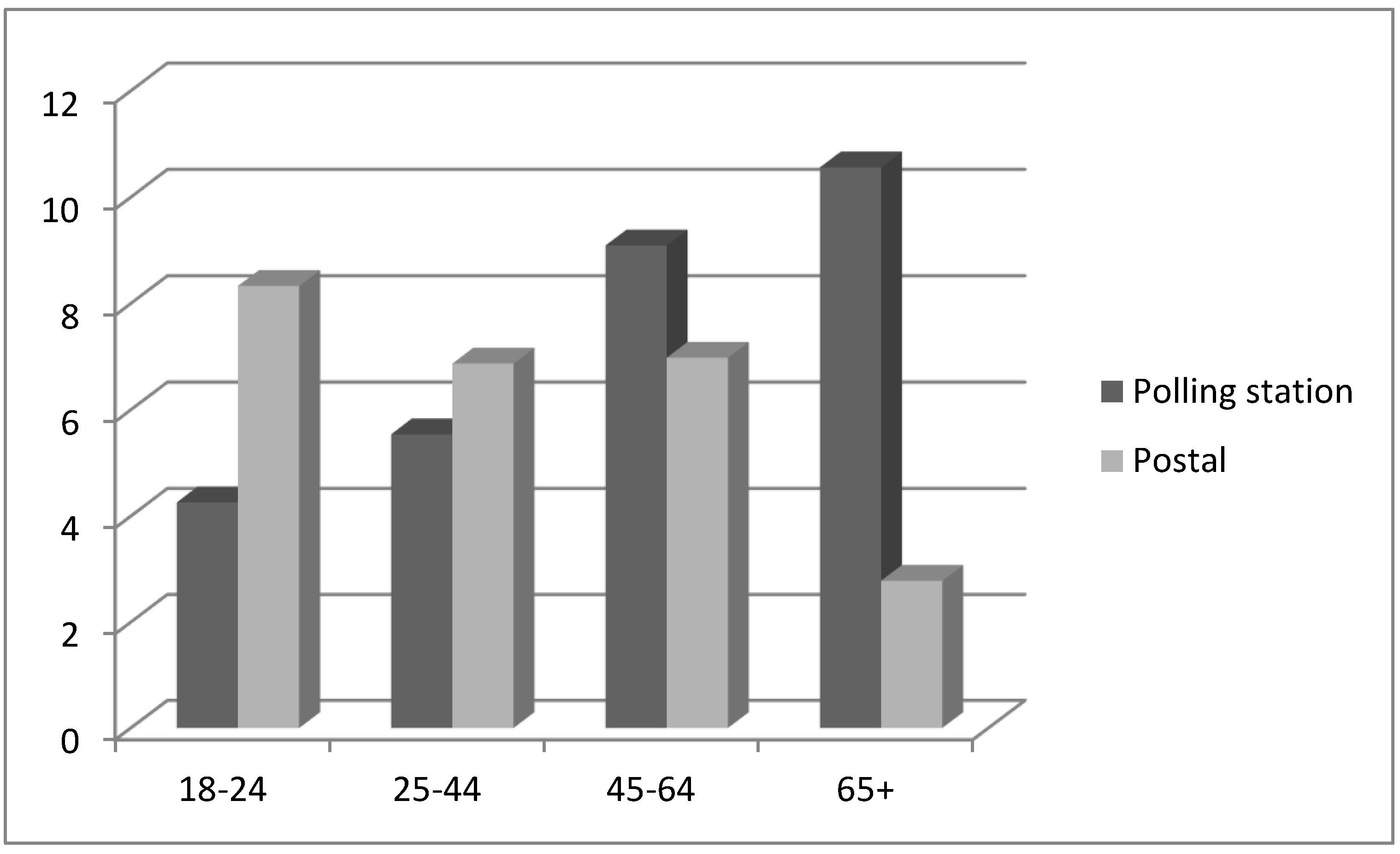

It is, however, perhaps more surprising that voting by post also affects the electoral choice of citizens, and that that impact varies by generation. This is shown in Figure 1. Critically, the findings showed that, when we looked at the youngest voters, aged 18–24, voting postally led to a very significant increase in propensity to vote for radical right parties (+93%, so nearly twice more than when voting in a polling station). Conversely, for voters aged 25–44, the proportion of radical right votes was 25.5% higher than for polling station voters. By contrast, however, as we considered citizens of older generations, the situation kept inversing. Old citizens, aged 45–64 years, and those 65 and over were progressively getting less (rather than more) likely to vote for radical right parties when they had to vote by post as compared to going to a polling station.

Figure 1.

Vote for radical right parties among polling station and postal voters – UK General Elections, 2010.

In order to verify that those results were not due to self-selection bias, we compared those differences to differences in propensity to vote for the three same parties as declared in the first wave survey (conducted three weeks before the election) by the exact same respondents. The results were interesting in two ways. First, in the pre-election sample, unlike actual vote differences, there was a homogeneous pattern of differences across age groups. Instead, in every group, the propensity to vote for extreme right parties was slightly higher (though not always significantly so) for people who later voted in a polling station than for those who voted from home. At the same time, those effects were minimal. The average propensity to vote for extreme right parties pre-election was 10.9% higher for young voters aged 18–24 who ended up voting in a polling station than those who voted postally (whilst their actual vote for those parties was nearly twice lower), 8.3% higher for those aged 25–44 (whilst their actual vote was 25% lower), 30% higher in the category of those aged 45–64 (close to the difference in actual votes) and 25.8% higher for those aged 65 and above (whilst in practice, the difference in actual votes was far higher than that). In other words, looking at pre-election propensity to vote results, those who ended up voting in person at polling stations were always moderately more likely to support extreme right parties in the first place compared to those who ended up voting postally, whilst our results showed that in practice, among young generations, their pattern of actual vote was, in fact, opposite with the postal voters more likely to cast a vote for an extreme right party in the end. By contrast, for older generations, the actual behaviour confirmed and amplified the patterns of differences in propensities to vote pre-election. Differences due to social desirability could similarly be excluded as those measures were taken using the exact same sample, and it is largely inconceivable that one would admit to a propensity to vote for the extreme right whilst hiding an actual vote for the same. It, therefore, seemed that the differences measured were related to the polling station experience and not to a form of pre-disposition, at least among young voters.

As mentioned earlier, those findings reinforced those uncovered by Cammaerts, Bruter, et al., [32,33]. They conducted experiments with young participants aged 15–17 who had never voted, recruiting them in six European countries, allocating them randomly to two groups invited to vote in a polling station or online, respectively. Their vote was for a mock election for youth representatives. Of course, the whole logic of convenience voting should result in those offered to vote on the internet, having a greater likelihood to participate and greater satisfaction, but in practice, Cammaerts, Bruter et al. found that it was exactly the opposite that happened. Indeed, turnout was lower among the internet voting group than among those invited to vote in a polling station, and the self-reported emotions of internet voters were also far more negative: 0.8 for internet voters vs 1.2 for polling station voters on a happiness scale of 0–2, and average scores 0.2 points above their polling station counterpart in terms of worry, and conversely lagging 0.2 points below on excitement. Those results also echoed those of Harrison [34] on young voters in the 2017 UK General Election.

On the whole, electoral ergonomics analysis, therefore, suggests that internet vote may lead to lower turnout and satisfaction compared to in station voting, whilst postal voting seems to lead to higher propensity to support radical parties compared to visiting polling stations specifically among young people (whilst third does not hold true for older generations). At a time when many Election Management Bodies worldwide consider internet voting the possible Holy Grail of convenience voting for the young (as well as a way to significantly cheapen the cost of organising elections), those findings suggest that it may instead lead to highly counter-productive results.

5.2. Case Study No. 2: Voters Deliberate Longer before Casting Their Vote When Casting a Paper Ballot as Compared to an Electronic One

The second case study pertained to a very different type of effect, assessing whether voting—always in a polling station—using a paper ballot or a Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting mechanism affects the time people spend deliberating on their vote before casting it.

Whilst we know that thinking longer about something can, of course, affect the conclusions that we draw, it should be noted that pragmatically, there may be normative arguments favouring both shorter and longer thinking times in the polling booth. Longer deliberation may lead to a better quality of decision and more thoughtful and sociotropic decision-making [3], but conversely, shorter deliberation may limit the time spent by voters in the polling booth and thereby shorten the length of voting queues, which many Election Management Bodies worry about. In fact, it is even possible that the arguments for longer or shorter thinking times may vary by country and type of election—our experiment used a nominal list with voters asked to vote for one candidate out of six potential ones on the list, which is amongst the simplest electoral choice mechanisms, but rationales could change for ranked voting systems (such as Single Transferable Vote or Alternative Vote) or ballots with multiple votes to be cast (such as typical US elections whereby voters will be asked to cast dozens of choices for different elections and referenda on a single ballot) [35].

With that in mind, the results of the experiment were very clear. Participants were randomly assigned to three different types of ballots—one electronic, emulating DRE voting machines, and two paper-based ones using mono-paper (where all the candidates are on the page, and voters tick the box that they support, as would be the case in countries like the UK and Germany) and poly-paper ballots (where one ballot paper is pre-printed for each potential candidate, and voters pick the one that they wish to vote for and slid it in the envelope provided without writing anything, as would be the case in countries like France and Israel).

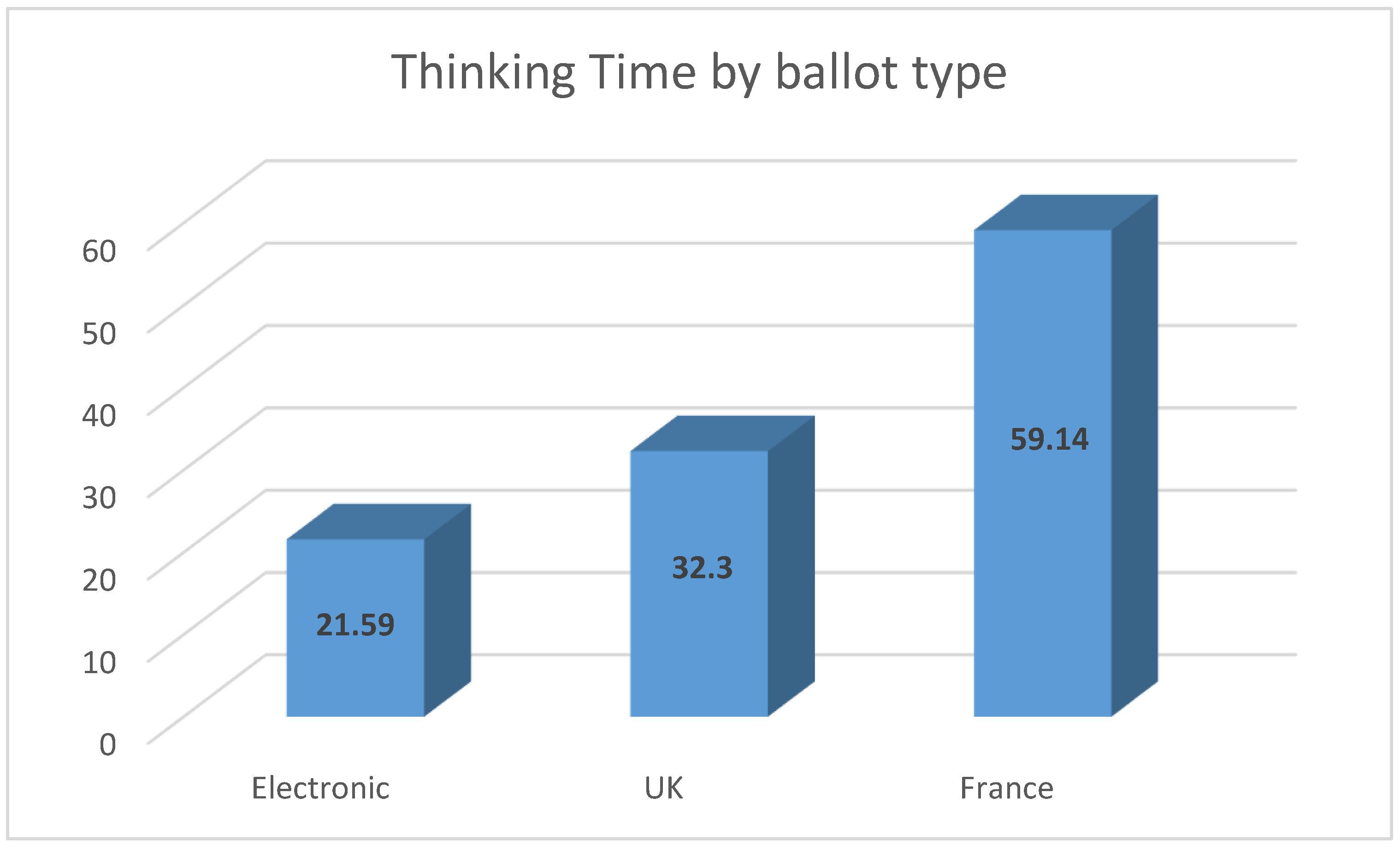

The results of the experiment are shown in Figure 2 and suggested that the average thinking times citizens took before casting their vote varied from 21.6 seconds when they were using an electronic vote (standard deviation 14.6) to 32.3 seconds under mono-paper physical ballots (standard deviation 12.6), and even 59.1 seconds with poly-paper ballots (standard deviation 19). In other words, it took citizens 3 times longer to think about their vote before finalising it with a materialised poly-paper ballot than with a voting machine, and 1.5 times longer under mono-paper materialised ballots. In addition to the figure, we ran a basic OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) regression to model thinking. It assessed the ways in which thinking time was affected by the material nature of the ballot paper and its single or poly-paper nature, whilst also controlling for age and gender. That regression confirmed that both paper support (b of 10.69, s.e. 1.95) and poly-ballot nature (b of 26.77, s.e. 1.69) had meaningful as well as statistically significant effects when it came to explaining voters’ thinking time. There was no statistically significant effect on either age or gender. The regression results are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Thinking time by type of ballot.

Table 1.

Modelling thinking time based on ballot characteristics.

6. Discussion: Electoral Ergonomics Matters: How Electoral Organisation and Electoral Psychology Work Together to Exceed the Sum of Their Parts

With the two case studies above, we saw the nature of electoral ergonomics at play. Notwithstanding whether different electoral arrangements bring additional people to vote, those arrangements lead the very same people to vote differently, thinking longer about their choice or even reaching different conclusions as a consequence of how those different electoral arrangements trigger different aspects of one’s electoral psychology, including memory, emotions or components of electoral identity. The results of our panel study data on support for extreme right parties also showed that the differences measured were related to the actual polling station experience and not to predisposition, at least among young people, as extreme right vote was higher among young postal voters than their polling station voter counterparts even though their original propensity to vote for extreme right party 3 weeks before the election was, on the contrary, lower.

Of course, it is not the place of this article to suggest whether it is preferable to have arrangements that make people more or less likely to vote for extremist parties, or whether it is a good or bad thing that citizens will think a little bit harder and longer about their vote before confirming it or not, but it is critical in any case to understand that those elements of societal experience, as well as solemnisation of the vote, have an impact on what aspects of a voters’ psychology will be triggered and meaningful in the context of their vote.

Electoral ergonomics is not about solely mechanical effects and even less so about merely basing an understanding of an aggregate level result based on who will take part in it. Rather, it is a model, which suggests that the way elections are designed will subtly influence the functions that citizens associate with them, their experience and their perception of the relationship between individual and collective aspects of an election. Electoral ergonomics is about switching on and off various aspects of a voter’s personality, memory, emotions and identity, just as we may react differently in discussion with others depending on where it takes place, the tone of their voice or the context in which it takes place. In that sense, electoral ergonomics is about electoral psychology and design very explicitly exceeding the sums of their parts and laying the ground for the way in which voters will also approach the future elections in which they will be invited to participate throughout the rest of their lives.

Funding

Some of the research discussed above was funded by the European Research Council’s Grants INMIVO (no241187), and ELHO (no788304), and a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC): First and Foremost (ES/S000100/1) jointly with Sarah Harrison.

Acknowledgments

Immense thanks are due to my co-investigator Sarah Harrison.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Duverger, M. Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- International Ergonomics Association Executive Council. August 2000. Available online: http://www.iea.cc/whats/index.html (accessed on 30 January 2017).

- Bruter, M.; Harrison, S. Inside the Mind of a Voter: A New Approach to Electoral Psychology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bruter, M.; Harrison, S. Understanding the Emotional Act of Voting. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipset, S.M.; Rokkan, S. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Grofman, B.; Lijphart, A. Electoral Laws and Their Political Consequences; Algora Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, G.; Press, C. Measuring Malapportionment. Am. Politi. Sci. Rev. 1964, 58, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, R.S. Malapportionment, Gerrymandering, and Party Fortunes in Congressional Elections. Am. Politi. Sci. Rev. 1972, 66, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansolabehere, S.; Snyder, J.M. The End of Inequality: One Person, One Vote and the Transformation of American Politics; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grofman, B. Political Gerrymandering and the Courts; Algora Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P.; Nai, A. Election Watchdogs: Transparency, Accountability, and Integrity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, J.A.; Banducci, S.A. Absentee Voting, Mobilization and Participation. Am. Politi. Res. 2001, 29, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedler, A.; Diamond, L.; Plattner, M. The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies; University of Colorado Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J.E. The Effects of Eligibility Restrictions and Party Activity on Absentee Voting and Overall Turnout. Am. J. Politi. Sci. 1996, 40, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronke, P.; Galanes-Rosenbaum, E.; Miller, P.A. Early Voting and Turnout. PS Politi. Sci. Politi. 2007, 40, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrnson, P.S.; Hanmer, M.J.; Koh, H.Y. Mobilization around New Convenience Voting Methods: A Field Experiment to Encourage Voting by Mail with a Downloadable Ballot and Early Voting. Politi. Behav. 2018, 41, 871–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, J.J.; Gimpel, J.G. Distance, Turnout and the Convenience of Voting. Soc. Sci. Q. 2005, 86, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokaji, D.P.; Colker, R. Absentee Voting by People with Disabilities: Promoting access and integrity. McGeorge L. Rev. 2007, 38, 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Neeley, G.W.; Richardson, L.E., Jr. Who is Early Voting? An Individual Level Examination. Soc. Sci. J. 2001, 38, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.A.; Streb, M.J.; Marks, M.; Guerra, F. Do Absentee Voters Differ from Polling Place Voters? New Evidence from California. Public Opin. Q. 2006, 70, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.C.; Caldeira, G.A. Mailing in the Vote: Correlates and Consequences of Absentee Voting. Am. J. Politi. Sci. 1985, 29, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, B.C.; Canon, D.T.; Mayer, K.R.; Moynihan, D.P. The Complicated Partisan Effects of State Election Laws. Politi. Res. Q. 2017, 70, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.M.; Hall, T.E.; Trechsel, A.H. Internet Voting in Comparative Perspective: The Case of Estonia. PS Politi. Sci. Politi. 2009, 42, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.K.; Lusoli, W.; Ward, S. Online Participation in the UK: Testing a ‘Contextualised’ Model of Internet effects. Br. J. Politi. Int. Relat. 2005, 7, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, N.; Baldersheim, H. Electronic Voting and Democracy. In A Comparative Analysis; Springer: Basingstoke, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.; Meredith, M.; Wheeler, S.C. Contextual Priming: Where People Vote Affects How They Vote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 8846–8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, M. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Democracies since 1945; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, A. To Vote or Not to Vote? In The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sproull, L.; Kiesler, S. Reducing Social Context Cues: Electronic Mail in Organizational Communication. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1492–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.K.; Olson, J.R.; Calantone, R.J.; Jackson, E.C. Print versus Electronic Surveys: A Comparison of Two Data Collection Methodologies. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electoral Commission. Report on the 2017 General Elections. 2017. Available online: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/UKPGE-2017-electoral-data-report.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Cammaert, B.; Bruter, M.; Banaji, S.; Harrison, S.; Ansted, N. Youth Participation in Democratic Life: Stories of Hope and Desillusion; Springer: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cammaert, B.; Bruter, M.; Banaji, S.; Harrison, S.; Ansted, N. The Myth of Youth Hapathy: Young Europeans’ Critical Attitudes toward Democratic Life. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S. Young People. Parliam. Aff. 2017, 71, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruter, M.; Harrison, S. Through the Polling Booth Curtain: A Visual Experiment on Citizens’ Behaviour inside the Polling Booth. In Voting Experiments; Blais, A., Laslier, J.F., Van der Straeten, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).