Abstract

The topic of gender differences in the propensity to vote has been a central theme in political behavior studies for more than seventy years. When trying to explain why the turnout gender gap has shrunk over the last few decades, some scholars have claimed that this might be due to the fact that women are more dutiful than men; however, no study to date has systematically addressed gender differences regarding the sense of civic duty to vote. The present research focused on such differences and empirically tested the role of political interest and moral predispositions on this gender gap. We explored duty levels in nine different Western countries and, most of the time, we found small but significant gender differences in favor of men. Our estimations suggest that this relationship can be explained mainly by the simple fact that women are less interested in politics than men.

1. Introduction

The topic of gender differences in the propensity to vote has always been keenly explored in political behavior studies. When trying to explain why women are less prone to vote than men, most scholars have resorted to resources and contextual explanations [1,2,3,4]. As the gender gap in this area has shrunk in recent decades, some scholars [5] have claimed that it might be due to the fact that women are more dutiful than men—but is this really the case?

The present work addressed the relationship between gender and the sense of duty to vote. Despite being one of the best predictors of the voting decision [6], the belief that voting is a duty still involves many unknowns, one of them being its relationship with gender. Indeed, no work to date has focused on the relationship between gender and the sense of civic duty to vote. Nevertheless, the existing literature on political participation and citizenship norms suggests a causal link between duty and gender, but two contradictory predictions have been made.

On the one hand, works on political engagement have pointed out that women are generally more politically alienated than men [7,8]. Since the feeling that voting is a civic duty refers explicitly to elections, women may exhibit lower levels of this attitude than men. On the other hand, works on social norms have pointed out than women embrace and enforce such norms more passionately than men, and therefore exhibit more stringent morals [9,10]. Since the sense of civic duty to vote is a social norm, one would expect women to have higher levels of duty as compared to men. Hence, the two causal paths appear to yield conflicting predictions. While the typically higher political engagement for men predicts that men will be more dutiful than women, women’s alleged higher moral standards should result in higher levels of perceived civic duty to vote for women than for men.

The present research addressed two questions. First, are women more or less prone to feel the call of the duty to vote than men? Second, what is the role of political interest and moral predispositions in the alleged gender gap with regard to the duty to vote? Addressing these questions should help us to inform the debate about the meaning of this sense of duty across different societies and genders, and contribute to the literature on the shrinking gender gap regarding turnout.

This research was based on two survey studies. The first was a cross-country survey conducted by the Centre d’Études Européenes of SciencePo (CEESP) immediately after the 2014 European elections in seven different West European countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Austria, Greece, and Portugal. The second was the Making Electoral Democracy Work (MEDW) dataset, which includes data on several national elections held in five different countries: France, Germany, Canada, Spain, and Switzerland, between 2011 and 2015. The inclusion of the same duty to vote indicator in both studies allowed us to extend our conclusions to nine different Western countries, as well as to assess the robustness of our results for the three countries for which we had two samples, drawn in different moments and contexts (France, Germany, and Spain). After testing differences in means between men and women regarding the duty to vote, we examined the mediating role of political interest and moral principles. Our results revealed that men have a slightly higher sense of duty than women. This modest relationship was explained mainly by the simple fact that women are less interested in politics than men. Our results tell a story consistent with our theoretical expectations that other explanatory factors (e.g. socialization, contextual and institutional factors) might be behind the observed differences between men and women.

2. Theoretical Framework

Gender has been among the main sociodemographic predictors of electoral behavior in the Western world since the beginnings of political behavior studies [11,12,13,14]. As soon as women were granted the right to vote, their persistently lower tendency to vote when compared to men became a research object in political science. Explanations for this gender gap in electoral participation [15,16] included differing resources (men being better off in all the skills and means that facilitate participation), differing effects (e.g., education is more mobilizing for women than for men), and differing contexts, namely traditional gender roles—passive for women—and late enfranchisement, which caused women’s lack of experience and political alienation. As a result, dominant social norms continued to discourage women from voting [17].

Although it was not a universal trend [5,18], several studies have pointed out that the gender gap diminished in the 1980s and 1990s, and that in some cases it was even reversed, with women exhibiting a higher propensity to vote than men [19,20].1 Given that most of the reduction in the gender gap over the years has been found to be due to generational changes [18], one could conclude that a drop in resource-based differences across genders as well as in cultural disparities is closing the turnout gap.

Recent developments have suggested new explanations for the reduction (and even reversal) of the turnout gender gap. For instance, Córdova and Rangel [21] found that compulsory voting is a very effective tool to close the gender gap, providing women with opportunities and incentives to vote, and more specifically to seek information and develop partisan identifications. This might also mean that an objective obligation might work as sufficient motivation for those lacking a subjective, inner obligation towards elections. Carreras (2018) elaborated on the mediating role of the sense of civic duty to vote for the relationship between gender and electoral participation. He argued that women exhibit higher turnout rates because they are more dutiful than men. Is this true? Are women more or less dutiful than men? Our research goes back one step in the causal chain that links gender and turnout and examines the relationship between the sense of duty to vote and gender.

Sense of civic duty is one of the overriding motivations for voting. “The dutiful person votes because she believes that it is the right thing to do: the good citizen should vote, and thus she feels that she has a moral obligation to vote even if she would not have done so otherwise” [23] (p. 478). The literature on the causes for this attitude is not ample, but it suggests that political socialization variables, such as non-authoritarian and engaged parenting styles, high family SES, and Catholic schools, can foster it [24]. We also know that it is positively related to a sense of belonging to a community [25,26] and certain personality traits [27,28]. However, the role of gender in the development of this civic attitude has not yet been explored.

An overview of the researches which have considered the sense of civic duty to vote as the main or secondary research object and which have included gender in their models yielded 14 works (see Table 1). Of these, one work did not reveal the results for the gender variable, and five did not find a significant effect of gender on the propensity to feel a duty to vote. Only one study found a negative effect, and seven found a positive effect of being a woman on the development of this civic duty. Nevertheless, in two cases this effect disappeared when controls such as political interest [29] or school-related variables [24] were included, and in one case the results were significant in only one of the samples used [30]. In sum, this overview showed mixed results for the effect of gender on duty.

Table 1.

Review of the literature on the effects of gender on the civic duty to vote.

Most works on the sense of duty to vote have started with the assumption that gender does indeed play a significant role in the development of this civic attitude, with women having a stronger sense of duty than men because of differences in the socialization process [6,31,32]. However, can we simply assume that women are socialized to think of voting as every citizen’s duty?

On one hand, the political behavior literature agrees that the differences between men and women when it comes to voting and other forms of participation are vanishing, due to the narrowing gender gap in educational attainment or labor force participation, among other advances in social integration [8,39]. Nevertheless, the differences in other relevant political attitudes persist, especially when it comes to political interest [7,8]. A differentiated socialization process for men and women appears to be at the heart of the gender gap as regards political interest, in the sense that men are socialized into more active, public-oriented roles, while women are guided towards a private, familiar, compassionate environment [40]. The patterns show up early in life, as boys have been consistently found to be more informed about politics than girls [41,42]. Following this train of thought, and as the sense of duty to vote refers explicitly to electoral politics, women will be less dutiful than men because they are less attracted to politics and elections.

However, it is not clear that this interest deficit extends to the feeling of duty to vote. Since Carol Gilligan [43] first posited that men and women had different moralities, based on justice (for men) or care (women), empirical research has confirmed (but toned down) her assertion. Women have been proven to be more interested in social welfare and community-oriented topics than men [44], and to be more deontological than utilitarian [10]. This means that women tend to judge something to be “good” depending on its consistency with moral norms rather than its consequences. In addition, and because of traditional gender roles, women tend to obtain a significant share of their self-esteem from social relationships [45,46,47]. As a result, the female social role is more linked to the community, which explains why women are less prone to immoral behavior than men [10]. Following this train of thought, women should score more highly on civic duty to vote because they have internalized the norm that the “good citizen” should vote.

A phenomenon that is closely related to morality is religiousness. In fact, the concept of duty is very close to religious thinking [48], as both religiousness and duty belong to the moral domain and the sub-domain of authority [49]. Extending the argument related to morality and duty, individuals that are more religious should also be more dutiful. In fact, it is a well-established finding that church attendance is positively related to turnout: those reporting regular church attendance are much more likely to vote [50,51]. We also know that women are more religious than men. When exploring the turnout decline in Canada, Blais and associates found in relation to women that “it is in good part because of their greater religiosity that they are as likely to vote as men” [52] (p. 232). Looking at the voting gender gap for left- and right-wing parties in Europe, Emmenegger and Manow wrote that a “substantial share of the old gender vote gap in the Southern European countries may have been due to the marked gender differences in religiosity” [53] (p. 176), as women have greater rates of church attendance. We can extend the norm-following reasoning to religious feeling, and posit that women will feel a stronger sense of duty to vote because of their higher levels of religiosity. In other words, since they are accustomed to thinking in terms of good, bad, and morality, religious women should embrace the sense of duty to vote more enthusiastically. Additionally, attending religious services would lead them to develop a sense of belonging to their community (i.e., to be even more aware and observant of social norms) and to be more likely to be mobilized during elections. However, this relationship is not so obvious. As Desposato and Norrander have stated: “some religious denominations reinforce traditional gender roles including less political activity on the part of women” [16] (p. 150).

In short, according to this perspective, women should exhibit higher levels of the subjective sense of duty to vote than men because, in general, they set more store by norms and moral rules, including religion. Nevertheless, the relationship between gender and ethical behavior is currently contested in the literature, with approximately the same number of works finding and not finding evidence of a relationship [54]. This brings forth another relevant aspect in this relationship: social desirability, a phenomenon that is especially acute among women. The role of social desirability was taken into account in this work by paying special attention to the measure of its outcome, the sense of duty (see the forthcoming section).

To sum up, our study empirically tests two competing expectations: first, that women will have lower levels of civic duty sense than men because the gender gap is mostly explained by political interest. Secondly, that men will have lower levels of civic duty sense than women because the gender gap is mostly explained by moral principles, a domain championed by women.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

Looking back to Table 1, another trait that stands out in the literature is the great diversity in the measures used to assess the sense of duty to vote. Blais has been especially emphatic in his criticism of the use of inaccurate instruments for approaching this phenomenon, given that questions on turnout are highly afflicted by social desirability—that is, respondents’ tendency to lie about their voting behavior in order to appear more socially admirable [55,56]. This flaw is especially present in questions about the importance of voting for being considered a “good citizen” [57]. As Blais and Achen [58] have pointed out and other works have confirmed [59], this wording yields very high averages because it points—too obviously—to a correct, socially acceptable behavior. The same applies to questions about turnout or duty that can be answered with a “yes”, which open the door to acquiescence bias [56]. Another common approach, asking whether respondents agree or disagree that voting is a duty, is no better, because it also induces acquiescence bias, presumably because there is an implicit social norm associated with being agreeable [56]. Hence, “good citizenship”, “yes/no”, and “agree/disagree” questions might be overstating the actual levels of women’s sense of duty to vote, given that women are more sensitive to such cues of social norms.3

Blais and Achen [23,59] have suggested a different approach that includes the word duty along with a positive “non-duty” option (choice) in order to keep social desirability and acquiescence at bay. This question is especially well-suited to addressing gender differences regarding the sense of duty to vote because it is (at least partially) free from the elements that might make women pay more lip service than men to the social norm that voting is desirable. For the sake of simplicity, we have referred to this question as the “choice” question. The question reads as follows: “Different people feel differently about voting. For some, voting is a DUTY. They feel that they should vote in every election, however they feel about the candidates and parties. For some, voting is a CHOICE. They feel free to vote or not to vote in an election depending on how they feel about the candidates and parties. For you personally, is voting in an election first and foremost a duty or a choice?” There is a follow-up question for those who answer “duty”: “How strongly do you feel that voting in an election is a duty: very strongly, somewhat strongly, or not very strongly?” Answers to these questions have been recoded into a new variable with values ranging from 0 (voting is a choice) to 3 (voting is a duty, very strongly).4

3.2. Data

Two studies conducted across several Western countries were used. Both studies included the Blais–Achen “choice” question in order to assess the dependent variable. First, we used the Centre d’Études Européenes at Sciences Po (CEESP) survey conducted in seven western European countries immediately after the 2014 European election. The countries were France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Austria, Greece, and Portugal.5 The survey also included several questions related to political interest and ethical issues.

The second study was the Making Electoral Democracy Work survey. Although this survey included the Blais and Achen “choice” question, it explicitly referred to four levels of elections (European, for the UE countries; national; regional; and municipal). For the sake of comparability with the CEESP dataset, only duty at the national level was considered.6

There were two main reasons to include these two different datasets. The first was the inclusion of as many countries as possible to strengthen the external validity of our conclusions. The second was to provide a robustness test by checking our initial results against a second sample for the three countries included in both surveys: France, Spain, and Germany. What varied for these cases from one study to another was the context of the fieldwork (after a European election in the 2014 CEESP study and before a national election in the MEDW study). If our results are similar regardless of the study and sample used, we will be able to conclude that our findings are impervious to different electoral contexts.

3.3. Variables

Table 2 summarizes the main variables used to analyze duty, gender, and the two crucial explanatory groups, political interest and morality, along with controls (age and education). All the datasets included a gender question that was coded 1 for female, 0 for not. We invite the reader to check our appendix (Appendix A) for more detail in the distribution of the gender and duty variables.7 Likewise, all the questionnaires included questions about age and education and a “choice” question. Religious attendance was measured on different scales in both studies, but both questions tapped into the same concept: the extent to which a person has a religious identity and socialization. Non-religious individuals were considered non-attendants. Note that this variable was not present in the German questionnaires in the MEDW study. We used this question to tap into individuals’ “moral stringency”. In this sense, the CEESP study had a question on the extent to which individuals believed that the State should impose higher levels of regulations. We are aware that this question might have been designed to tap illiberal attitudes, but its relationship with ideology was close to zero (Pearson’s r = − 0.06), and therefore we believe that it tapped into respondents’ attitudes regarding authorities and the enforcement of what is right. We ran a principal component factor analysis using this question and religious attendance, then kept the resulting factor which we labeled “morals”.8 This and the other independent variables were rescaled to range between 0 and 1, in order to compare how they contributed to explaining duty.

Table 2.

Operationalization of the main variables for each dataset. CEESP: Centre d’Études Européenes of SciencePo; MEDW: Making Electoral Democracy Work.

3.4. Methods

We first conducted a series of mean comparisons of the levels of sense of civic duty to vote between men and women (i.e., t-tests). Next, to clarify how explanations based on political interest and on moral principles contribute to the gender gap, a series of OLS estimations were conducted. All of them featured age and education as controls, and sequentially introduced one of the two alternative explanations for the gender gap (interest and morals) to see which one was more successful in reducing the gender gap. Note that this strategy is consistent with Baron and Kenny’s [62] approach to testing mediation effects. Assuming that gender is the exogenous, independent variable that might be causing a lack of political interest or a more “moral” viewpoint of politics (the two potential mediators for the effect of gender), ultimately affecting sense of duty, the effect of gender should disappear or at least decrease when a mediator is included as a control.

4. Results

A first approach to the differences between men and women with regard to the sense of duty to vote is presented in Table 3 and Table 4. Averages of the sense of duty to vote (always ranging between 0 and 3) for both genders and all samples are presented and have been highlighted when differences across genders were significant.

Table 3.

CEESP 2014. Duty averages by gender and country.

Table 4.

MEDW (2011–2015). Duty at the national level. Averages by gender and country.

In the first dataset (see Table 3), the gender gap for the “choice” question was significant in five of the seven countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Austria), with women being less dutiful than men in all cases. Where differences were not significant according to a two-tailed t-test (Greece and Portugal), men were still more dutiful than women. As for the MEDW dataset (Table 4), there was a significant gender gap regarding the sense of duty to vote at the national level in four of the five countries included in the study (Switzerland, France, Germany, and Canada); in all instances, women were less dutiful than men. It is noteworthy that if when comparing the CEESP and the MEDW outputs, we found consistent results for France and Germany, while the results for Spain diverged.

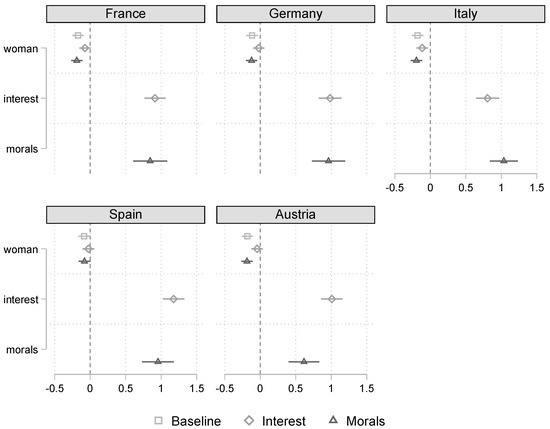

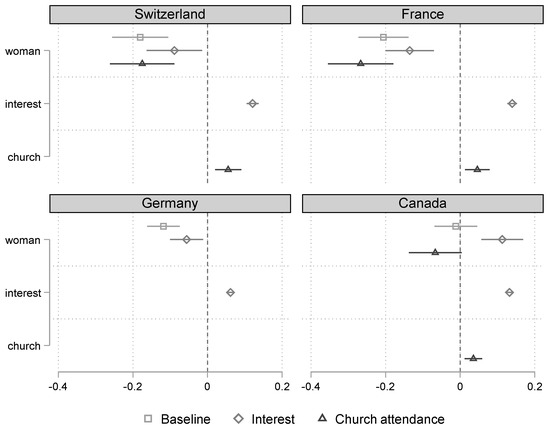

Figure 1 and Figure 2 reveal the results of estimating the effects of sex, interest, and morals by means of a series of OLS regressions using the CEESP and the MEDW datasets, respectively, considering the samples where significant gender gaps were previously observed. All the estimations included age and educational level as controls, although their coefficients (along with the constant) have not been displayed for the sake of brevity.

Figure 1.

Alternative models to explain the gender gap regarding the duty to vote (CEESP).

Figure 2.

Alternative models to explain the gender gap regarding the duty to vote (MEDW).

The CEESP study (Figure 1) revealed that the gender gap in the sense of duty to vote persisted even when age and education were taken into consideration (see the baseline coefficient for “woman”), with women being less dutiful. The first alternative model included an additional variable: interest in politics. In all instances, this variable had a significant, positive effect on sense of duty, which was slightly stronger in Spain. Most interestingly for the purposes of our research, the introduction of political interest caused a reduction in the effect of the gender variable in all cases, to a point that being a woman was no longer significant in four of the five cases analyzed. The third estimation substituted interest by the composite indicator that tapped into individuals’ moral stringency. This variable had a sizeable effect on sense of duty. Its inclusion, however, caused only minor variations in the gender coefficient, most of the time exacerbating the observed gender gap.

We then focused the MEDW dataset, and more specifically on the countries that revealed a gender gap: Switzerland, France, Germany, and Canada. Figure 2 depicts the results of three OLS estimations for the duty to vote. When age and education were taken into consideration, the observed gender gap in Canada disappeared, which might suggest that differences between men and women regarding the sense of civic duty in that country might be explained by differential resources and demographic factors. The model featuring interest in politics obtained positive, significant coefficients for this variable in the four countries studied, and produced remarkable reductions in the effect of gender in Switzerland, France, and Germany, almost making the gender gap disappear in Switzerland and Germany. Where church attendance was asked about in the questionnaires (everywhere but Germany), this variable contributed significantly to the explanation of duty by boosting it, but it did not reduce the gender gap.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Previous research has failed to examine the relationship between gender and the sense of duty to vote. Our research addressed this shortcoming by studying the relationship between gender and the sense that voting is a citizen’s duty. It posited two possible explanations for differing levels in sense of duty across genders: political interest and morality. According to the first explanation, men should be more dutiful than women because they are more politically motivated, and the electoral referent in the “duty to vote” would repel more women than men. According to the second explanation, women are more tied to social norms and are more aware and more observant of conventions than men; they also tend to think more in terms of “good vs. bad” and because of this, they should manifest higher levels of sense of duty to vote.

The difference between men and women was explored using two different studies, which examined nine different western countries through 12 different samples (France, Spain, and Germany were repeated twice). The results yielded significant differences in favor of men nine times out of 12, but the difference was quite small. The results for France and Germany, obtained by two different studies at different moments in time, consistently showed a gender gap, with men being more dutiful. The results for Spain were non-significant in one case (MEDW) and significant in the CEESP 2014 data, which suggests that second-order elections (more precisely, the European ones) were less able to trigger the sense of duty to vote among Spanish women. The results for France and Germany, though, seemed impervious to electoral context. In two cases (Portugal and Greece, CEESP study), the non-significant results might have been due to small samples, and raw differences suggested that increasing the sample would yield significant gender gaps, again in favor of men. The similarities between these two countries and other Southern European countries included in the study suggests that similar relationships between political interest, duty, and gender might have been found if larger samples had been available. No evidence was found that points to a gender gap in favor of women. In all the countries analyzed, men were more dutiful than women, or there were no significant differences present. Given the diversity of countries analyzed, we can presume that these results are likely to be replicable in other established Western democracies.

Once the existence and direction of the gender gap regarding the duty to vote was established, we proceeded to examine the roles of interest and morality as causal mechanisms for this gap. The results of a series of linear regressions confirmed that only the inclusion of interest made the observed gender gap shrink, except for in Canada, where gender differences might have been due to a different distribution of resources between men and women. For the other cases, political interest appeared to be a plausible mediator for the effect of gender on duty. This suggests that getting women interested in politics (for instance, by discussing public policies that are closer to their interests or by presenting more female candidates) will most likely spur their sense of duty to vote and, ultimately, increase their turnout levels. It also points to an indirect effect: active political socialization might cause higher levels of interest in politics, which ultimately boosts sense of duty. Our results encourage further research on the socialization dynamics that pave the way for a passive female political role, consistent with previous research on the matter [7,39]. Among the main limitations of the present study, we highlight the lack of better and more complex variables able to tap into moral considerations, which we only roughly approximated here using church attendance. We acknowledge that this limitation might be downplaying the actual role of morals on the gender gap. More duty questions would also have been welcomed to help build composite measures free from measurement error. Ideally, a diachronic approach would have been useful to check whether the gender gap detected was shrinking or widening. Further research should address these shortcomings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, C.G. and A.B.; software, C.G.; formal analysis, C.G.; resources, A.B.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.; writing—review and editing, C.G. and A.B.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, C.G.; funding acquisition, A.B. and C.G.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under the Insight Grant program [grant number 435-2014-0077].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Appendix A

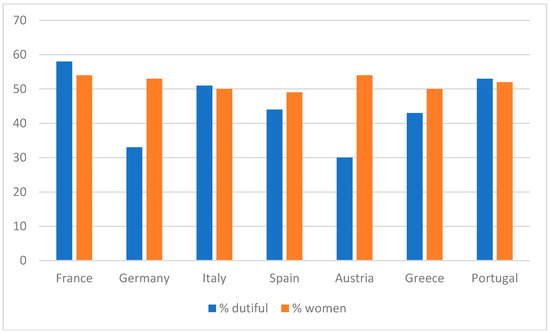

Figure A1.

Percent of dutiful citizens and women per country (CEESP).

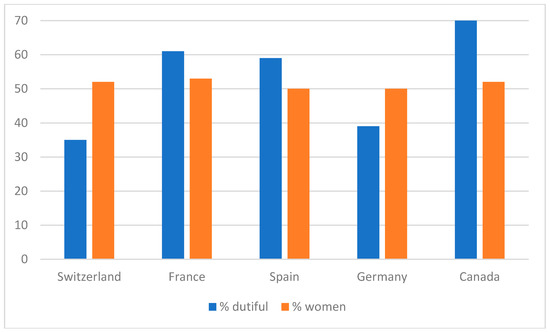

Figure A2.

Percent of dutiful citizens and women per country (MEDW).

References

- Norris, P. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, M.N. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, N. Sociologie des Comportements Politiques; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.S. Traditional Gender Gap in a Modernized Society: Gender Dynamics in Voter Turnout in Korea. Asian Women 2019, 35, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, M. Why no gender gap in electoral participation? A civic duty explanation. Elect. Stud. 2018, 52, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A. To Vote or Not to Vote? The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburg, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fraile, M.; Gomez, R. Bridging the enduring gender gap in political interest in Europe: The relevance of promoting gender equality. Eur. J. Political Res. 2017, 56, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, N.; Schlozman, K.L.; Jardina, A.; Shames, S.; Verba, S. What’s happened to the gender gap in political participation? How might we explain it? In 100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment: An Appraisal of Women’s Political Activism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Li, T.; Hamamura, T. Societies’ tightness moderates age differences in perceived justifiability of morally debatable behaviors. Eur. J. Ageing 2015, 12, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesdorf, R.; Conway, P.; Gawronski, B. Gender differences in responses to moral dilemmas: A process dissociation analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingsten, H. Political Behavior: Studies in Election Statistics; King and Son: London, UK, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, S.; Gabriel, A. The Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations; Princeton university press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Rokkan, S. Citizens. Elections, Parties; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, S.; Nie, N.H. Participation in America: Social Equality and Political Democracy; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Engeli, I.; Ballmer-Cao, T.H.; Giugni, M. Gender gap and turnout in the 2003 federal elections. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2006, 12, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Desposato, S.; Norrander, B. The gender gap in Latin America: Contextual and individual influences on gender and political participation. Br. J. Political Sci. 2009, 39, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K. After Suffrage: Women in Partisan and Electoral Politics before the New Deal; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P.A. gender-generation gap? In Critical Elections: British Parties and Voters in Long-Term Perspective; Evas, G., Norris, P., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999; pp. 743–758. [Google Scholar]

- De Vaus, D.; Ian, M. The changing politics of women: Gender and political alignment in 11 nations. Eur. J. Political Res. 1989, 17, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, S.; Schlozman, K.L.; Brady, H.E. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, A.; Rangel, G. Addressing the gender gap: The effect of compulsory voting on women’s electoral engagement. Comp. Political Stud. 2017, 50, 264–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, B.C. Gender, Presidential Elections and Public Policy: Making Women’s Votes Matter. J. Women, Politics Policy 2005, 27, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, A.; Achen, C.H. Civic duty and voter turnout. Political Behav. 2019, 41, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galais, C. How to Make Dutiful Citizens and Influence Turnout: The Effects of Family and School Dynamics on the Duty to Vote. Can. J. Political Sci./Rev. Can. De Sci. Polit. 2018, 51, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, T.; Berdahl, L. Birds of a feather? Citizenship norms, group identity, and political participation in Western Canada. Can. J. Political Sci. Rev. Can. de Sci. Polit. 2009, 42, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galais, C.; Blais, A. Duty to Vote and Political Support in Asia. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2016, 29, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinschenk, A.C. Personality traits and the sense of civic duty. Am. Politics Res. 2014, 42, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; St-Vincent, S.L. Personality traits, political attitudes and the propensity to vote. Eur. J. Political Res. 2011, 50, 95–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millican, A.S. Voting: Duty, Obligation or the Job of A Good Citizen? An Examination of Subjective & Objective Understandings of These Drivers and Their Ability to Explain Voting Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exete, Exete, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H. Political trust, civic duty and voter turnout: The Mediation argument. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmensen, R.; Hatemi, P.K.; Hobolt, S.B.; Petersen, I.; Skytthe, A.; Nørgaard, A.S. The genetics of political participation, civic duty, and political efficacy across cultures: Denmark and the United States. J. Theor. Politics 2012, 24, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, S.; Donovan, T. Civic duty and turnout in the UK referendum on AV: What shapes the duty to vote? Elect. Stud. 2013, 32, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, J.A.; Brockington, D. Social desirability and response validity: A comparative analysis of overreporting voter turnout in five countries. J. Politics 2005, 67, 825–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, P.J.; Christopher, T.D. The heritability of duty and voter turnout. Political Psychol. 2012, 33, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinschenk, A.C.; Dawes, C.T. Genes, personality traits, and the sense of civic duty. Am. Politics Res. 2018, 46, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Nørgaard, A.S.; Klemmensen, R. The civic personality: Personality and democratic citizenship. Political Stud. 2014, 62, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, A. Is there an intrinsic duty to vote? Comparative evidence from East and West Germans. Elect. Stud. 2017, 45, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Galais, C.; Mayer, D. Is It a Duty to Vote and to be informed? Political Stud. Rev. 2019. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1478929919865467?journalCode=pswa (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Bennett, L.L.; Bennett, S.E. Enduring gender differences in political interest: The impact of socialization and political dispositions. Am. Politics Q. 1989, 17, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwin, D.F.; Cohen, R.L.; Newcomb, T.M. Political Attitudes over the Life Span: The Bennington Women after Fifty Years; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, R.D.; Torney, J.V. The Development of Political Attitudes in Children; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deth, J.W.; Abendschön, S.; Vollmar, M. Children and politics: An empirical reassessment of early political socialization. Political Psychol. 2011, 32, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C. In A Different Voice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.; Winters, K. Understanding men’s and women’s political interests: Evidence from a study of gendered political attitudes. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 2008, 18, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Madson, L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 122, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kim, U.; Choi, S.C.; Gelfand, M.J.; Yuki, M. Culture, gender, and self: A perspective from individualism-collectivism research. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, S.M.; Dollinger, S.J. Identity, self, and personality: I. Identity status and the five-factor model of personality. J. Res. Adolesc. 1993, 3, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaluso, T.F.; Wanat, J. Voting turnout & religiosity. Polity 1979, 12, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.; Nosek, B.A.; Haidt, J.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Ditto, P.H. Mapping the moral domain. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstone, S.J.; Hansen, J. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, A.S.; Gruber, J.; Hungerman, D.M. Does church attendance cause people to vote? Using blue laws’ repeal to estimate the effect of religiosity on voter turnout. Br. J. Political Sci. 2016, 46, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Gidengil, E.; Nevitte, N. Where does turnout decline come from? Eur. J. Political Res. 2004, 43, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmenegger, P.; Manow, P. Religion and the gender vote gap: Women’s changed political preferences from the 1970s to 2010. Politics Soc. 2014, 42, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, D.; Ortegren, M. Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, A.L.; Krosnick, J.A. Social desirability bias in voter turnout reports: Tests using the item count technique. Public Opin. Q. 2009, 74, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, J.; Krosnick, J.A. Optimizing survey questionnaire design in political science: Insights from psychology. In Oxford Handbook of American Elections and Political Behavior; Leighley, J.E., Edwards, J.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, R.J. Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Stud. 2008, 56, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Achen, C.H. Taking Civic Duty Seriously: Political Theory and Voter Turnout. 2010; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, A.; Oberski, D. Personality and political participation: The mediation hypothesis. Political Behav. 2012, 34, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, N.J. Reconceptualizing Civic Duty: A New Perspective on Measuring Civic Duty in Voting Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, A.; Galais, C. Measuring the civic duty to vote: A proposal. Elect. Stud. 2016, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Curiously enough, academic interest in the turnout gender gap increased precisely when this gap started to shrink. Referring to the US arena, Barbara Burrell stated: “Gender became a central focus of campaigns in the aftermath of the 1980 election for two reasons: (1) numbers and (2) opinions. Women became not only the majority of voters, they began to turn out in higher percentages than men; thus if they had distinct perspectives on issues and the candidates, they would decide the elections” [22] (p. 33). |

| 2 | More recent research by Weinschenk and Dawes [35] reported bivariate analyses using the MIDUS dataset (1995–1996). This revealed a lower duty to vote for women. |

| 3 | For a discussion on the different measures of civic duty employed so far in different public opinion surveys, we redirect the reader to Goodman [60]. She distinguishes between direct/indirect, negative/ positive, and personal/general formulations. “It is every citizens’ duty to vote in federal elections” (Canadian National Election Study 2004) would be general, positive, and direct. “If I did not vote, I would feel guilty” (Canadian National Election Study 2000) would be indirect, personal, and negative. On the matter on how these different formulations would alter women’s answers, we can only be speculative. Direct, positive, and general questions being more prone to triggering social desirability, and women being more sensitive to such bias, a question such as the first one would be more prone to detecting unreliable high levels of duty among women. The Blais–Achen “choice” question is a positive, personal, and direct one that offers a worthy non-duty option and avoids acquiescent answers, hence it is less likely to be affected by gender-influenced social desirability bias than previous formulations. |

| 4 | Note that, among the articles reviewed in Table 1, four used this very same “choice” question. Blais and Labbé St. Vincent [28] used it in combination with five other questions in order to produce a composite measure. Another study [5] used it in combination with three other indicators, following Blais and Galais’ advice [61]. In the first case, there were no significant effects for the gender variable, and in the other, the female coefficient in a multivariate analysis showed a positive, significant effect. Although using a composite measure is the best possible strategy to deal with measurement error problems, we only used one question in this research in order to be able to compare across different surveys. Among the studies using only the “choice” question, Galais [24] found a positive effect of being a woman on duty—which disappeared when including school-related variables—and Blais et al. [38] found a negative effect (women being less dutiful), which disappeared when attitudinal controls were considered. |

| 5 | Note that this is the same study that was used by Carreras [5], but that we only used one of the available civic duty indicators. The survey was an initiative of the Centre d’Études Européenes at Sciences Po, Paris (P.I. Nicolas Sauger). The online survey was conducted by TNS Sofres between May 28 and June 12, 2014, immediately after the European election. This was a non-probabilistic online survey that used sex, age, and social status quotas. All samples gathered slightly more than 4000 individuals except for Portugal and Greece, for which the samples were only about 1000 individuals due to the difficulty of finding large balanced samples. Average response rate was above 30%. |

| 6 | Of the 25 surveys that were conducted in the MEDW study, only 11 were selected: those that corresponded to national elections. Each survey was conducted in two waves: one in the week or so before the election and one in the period immediately after the election. All the questions used for this study were retrieved from the pre-election questionnaires. The samples for each country were the result of combining the surveys conducted in two (or three) regions within each country. Hence, the Swiss sample resulted from pooling the Lucerne (N = 1108) and the Zurich (N = 1057) national electoral surveys. The French sample pooled surveys from Île-de-France (N = 966) and Provence (N = 983). The Spanish sample combined the surveys conducted in Catalonia (N = 951) and Madrid (N = 976). The German sample used the surveys conducted in Bavaria (N = 4680) and Lower Saxony (N = 975). Finally, the Canadian sample resulted from pooling national electoral surveys conducted in Ontario (N = 1891), British Columbia (N = 1869), and Quebec (N = 1849). |

| 7 | The percentage of women was close to the 50% for all the samples, ranging from 49% (Spain, CEESP) to 54% (Austria, CEESP). The percentage of dutiful citizens ranged from 35% (Switzerland, MEDW) to 72% (Canada, MEDW). As for the countries sampled in both studies, Germany had 33% dutiful citizens according to the CEESP and 39% according to the MEDW. France had 58% in the CEESP and 61% in the MEDW. Discrepancies for Spain were somewhat more remarkable, with 44% dutiful citizens according to the CEESP study and 59% according to the MEDW surveys. |

| 8 | This decision resulted in a composite independent variable (“morals”) that had a higher correlation with duty (r = 0.15) than religious attendance alone (r = 0.13). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).