Abstract

Academic freedom is formally supported but often challenged, through activities like no-platforming and through a sentiment of sensitivity and an understanding that ideas can be harmful. This development is discussed here as a reflection of the rise of the ‘vulnerable subject.’ This paper demonstrates the growing importance of vulnerability as the central human characteristic in (post) modern times and with reference to law and justice practices explains the ‘collapse of the harm principle.’ Developed through Frank Furedi’s theory of diminished subjectivity we will demonstrate the extent to which the vulnerable subject has been institutionalised and adopted as a new (fragmented) norm. Within the framework of diminished subjectivity, the inner logic of vulnerability has a spiralling dynamic—once adopted as a norm, the vulnerable subject’s answer to the question ‘vulnerable to what?’ constantly expands, drawing in ever more areas of life, behaviour, relationships as well as words and ideas into a regulatory framework. Concerns about overcriminalisation are understood here to be a product of this vulnerable subject, something that cannot be resolved at the level of law but must relate to the wider cultural and political sense of human progress and a defence of the robust liberal subject in society.

Keywords:

criminalisation; harm; law; criminal justice; freedom; risk; abuse; liberal; victim; vulnerability 1. Introduction

Concerns about academic freedom and free speech on campus have resulted in reactions from the British government and from Barack Obama in the United States. There is talk of a ‘snowflake generation’ and growing questions about the apparent need for safe spaces or the need for university practices to incorporate an awareness of microaggression [1]. There are also calls from academics to be supported in areas of research regarding controversial topics like transgender rights [2].

Outside of universities, in both the UK and US there are similar concerns being raised about issues like hate crime and the potentially censorious developments within law and policing practices that limit speech and to some extent thought [3].

Critical responses to these developments relate, at times and at a ‘populist’ level, to the idea of ‘political correctness gone mad’ and there is a concern about identity-based activists enforcing their will on society and undermining once liberal institutions [4]. More generally and perhaps more usefully there have been discussions about what Tana Dineen has called the Manufacture of Victims, that help to situate these developments in a broader context, albeit, with a preponderance to once again see a different will at fault, that of psychologists or of what the psychology industry is doing to people, as Dineen’s subtitle asserts [5].

While at times useful and relevant, these critical voices tend to give too much weight to the role of activism and willing actors in creating a climate of regulation and limits. Aggressive victimhood is a reality but behind it lies the more difficult and fundamental problem not of the wrongheaded willing actor but the loss of will itself, something that is explained most usefully through the idea of diminished subjectivity [6] and what we will call the vulnerable subject. In this Baudrillardian [7] meets Bauman [8] nightmare, we find the black hole of the silent majority (or the loss of a public) meets the pilotless aeroplane (or the loss of a meaningful elite) in a perfect subjectless storm.

The focus on identity politics can be useful but also misses the universal aspect of the vulnerable subject. Vulnerability is not only associated with the caricatured ‘vulnerable groups’ but has become a framework for the state and institutions to connect with the public in general.

The aim of this paper is to examine the emergence and centrality of vulnerability as a core human characteristic in general and to unpick more specifically the emerging significance of vulnerability within the field of law and in criminal justice practices. We do this, firstly through an examination of the growing use of the term ‘vulnerability’ itself, in books. Then through a study of various areas and organisations where the term vulnerable, vulnerability and vulnerable groups, is used. And within this we focus on law and criminal justice organisations. Theories related to the idea of a culture of limits and the growth of risk management are adopted to make sense of these developments, with the idea of diminished subjectivity being central to how we interpret the growth of the idea of vulnerability as an essential human condition in the later part of the twentieth century and into the new millennium.

There is a struggle within law between the historically robust legal subject and the new, fragile vulnerable subject that appears to be replacing it—a subject that has the tendency to accelerate the criminalizing process and to potentially undermine justice. Within legal theory itself there is a clear sense that aspects of justice are being warped or lost, in part because of the drive towards ever further criminalisation. There is also a sense of confusion about how to explain this development. Here we suggest that this can be best understood through the idea of the vulnerable subject, a fragile subject that, once incorporated into criminal justice processes, helps to undermine the classical liberal idea of the legal and crucially, robust, human subject.

This confusion in legal theory is in part explained by the semi-conscious (rather than ideologically driven) transformation, over time, of many liberal categories that has resulted in not only their loss of meaning but in many categories coming to mean the opposite of what they once did. Talk of tolerance comes from the same people arguing for zero-tolerance policies, while the promotion of freedom becomes associated with the idea of freedom from fear or in other words with policing and the regulation of other people.

Perhaps the most insightful legal theorist, Peter Ramsay, in his book The Insecurity State, has defined the modern legal framework as one predicated upon the idea of ‘vulnerable autonomy’ [9]. The prior and dominant term being that of vulnerability, something that in practice undermines the very essence of individual autonomy. His subtitle, Vulnerable Autonomy and the Right to Security in the Criminal Law, hints at another modern transformation in liberal categories, that of rights, a shift that sees rights increasingly developed by institutions as a form of protections rather than as the basis for individual freedom.

2. The Vulnerable Person

Vulnerable: Adjective: exposed to the possibility of being attacked or harmed, either physically or emotionally.

Synonyms: in danger, in peril, in jeopardy, at risk, endangered, unsafe, unprotected, ill protected, unguarded.

In 2017, the BBC reported on a little known police database in Scotland that was breaching data protection laws. The Vulnerable Person Database or VPD had been set up in 2013 to provide a ‘holistic’ approach to adult and child protection and wellbeing. Within four years one in 13 Scots was on the list. Many on the list do not know they are on it or know that they have been defined as vulnerable. One such individual, John Naples-Campbell, despite having reported suffering ‘homophobic abuse’ shouted at him was ‘shocked’ to find that he was on the list, explaining to the BBC that, ‘I don’t see myself as a vulnerable person’ [10].

The database was set up in anticipation of the Child and Young Person Scotland Act 2014 that controversially included the creation of a ‘Named Person,’ what some called a ‘state guardian’ for every child in Scotland. Under the Named Person scheme every child would have a state named individual to oversee their ‘wellbeing’ from birth (or before birth through the use of health visitors as the initially designated Named Person). The Named Person scheme has also been found guilty of breaching data protection laws by the UK Supreme Court and is currently being revised.

Asked about the VPD, Detective Chief Inspector Conway explained that Police Scotland were acting legally in terms of their core purpose, of ‘improving safety and wellbeing.’ Legal expert, Professor Jim Murdoch, likewise explained to the BBC that it was a very positive sign because public authorities have a duty to protect the vulnerable. Who ‘the vulnerable’ are however is unclear. For Police Scotland, at least, the numbers of vulnerable Scots has been growing year on year.

3. The Rise and Rise of Vulnerability

Using Google Ngrams (a search through Google looking at books from 1800 to 2000) we find that the use of the term ‘vulnerable’ remained fairly constant from 1800 until 1929 when it started to increase. The use of the term in books accelerated from the late 1960s and continues to rise1.

It is worth noting that Google Ngrams is both useful and potentially problematic because simply through the use of the graphs that show frequency of word use, like the word ‘vulnerable,’ you get no sense of how these words are being used or what they relate to without studying the actual texts from which they came. It is possible for example that the use of the term vulnerable relates to something completely unrelated to what is being discussed here. Hopefully, further examples and evidence in the paper strongly suggests this is not the case. In this respect Ngrams is heavily interpretive and needs further work and different methods of analysis and understanding to be of use. This said, clear trends can be seen in the terms analysed below, with very similar patterns of word usage and growth of usage suggesting a clear and growing significance in the idea of human vulnerability.

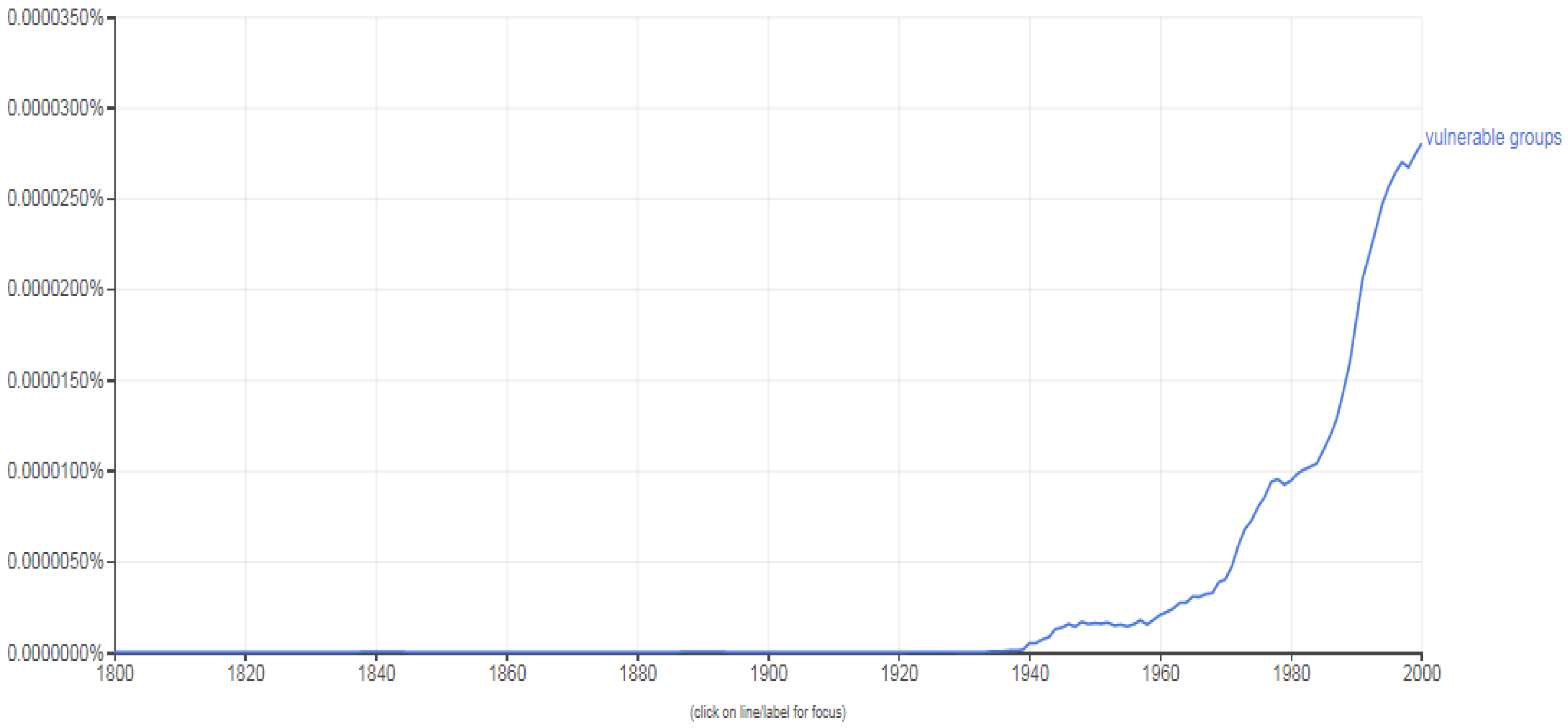

Looking at the term ‘vulnerable communities’ we find it is first used (within this data source) in an American research monograph discussing depressed areas in The Plantation South in 1935. However, this term was rarely used until 1970 when there was an exponential increase up to 1990 when we see a further accelerated use of the term (NB in 2015 Google had scanned 25 million books having estimated in 2010 that there were 130 million books worldwide). Between 1970 and the year 2000 there had been a 30 fold increase in the use of the term ‘vulnerable communities.’ See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vulnerable Groups.

Searching the term ‘vulnerable groups’ (above) we find the odd use of the term but the first recorded document is in a journal, the National Negro Health News published by the Federal Security Agency U.S. Public Health Service in 1942 used for ‘guidance in planning and conducting the community health program’ [11]. In particular the term ‘vulnerable groups’ (with the accompanying speech marks) related to the need to improve the food supply for key sections of the black population, specifically ‘pregnant women, infants, school children (especially adolescents) workers in heavy industries and the poor, particularly those with large families.’ Again, the term was rarely used until the 1960s when it increased slightly, accelerating from 1970 and then again in the late 1980s. To give a sense of the increase of books that use the term ‘vulnerable groups,’ there were 136 times more uses of the term in Google books in 2000 as there was in 1960.

Based on these findings we can argue that the term ‘vulnerable’ is used far more today than at any other time in the last 200 years. The use of the term was constant throughout the nineteenth century and into the 1920s. We use the term thirteen times more than we did then. Until the 1930s and only very infrequently was the term used with reference to a particular group or community. From the 1970s this began to change and today a vast array of groups are labelled as being vulnerable simply by being part of a certain defined group.

The idea of vulnerability is now used in relation to more issues and experiences, it has also become used to define or label certain sections of society, in particular those sections of society that are understood to have suffered political oppression or other forms of inequality, as well as other groups who are incorporated into this politicised category, like the disabled [12]. More generally, studying the use of the term in these books and in other documents, policies and best practice guides we find that children, for example, have become discussed, relatively unquestioningly as vulnerable, as have the elderly, as have students.

The term has historically related to economic conditions and ill-health and to environmental issues. Increasingly, as we will demonstrate, it relates to mental health matters, to abuse and to our fragility in relation to other people. Looking at the issue of poverty, it is noticeable that only specific sections of the poor were originally identified as being part of a vulnerable group, only certain black people who were poor but for example who were also part of a particular population in America and who were also part of a ‘large family.’ Today in comparison, living in poverty itself is assumed to mean you are vulnerable, where, for example in the discussion about vulnerable children we find this definition of poverty and vulnerability refers not to absolute poverty or food poverty, but, in the case of the UK Department of Health approach, four million vulnerable children are so labelled because they live in families with less than half the average household income [13]. Again, the question can be raised about the extent to which these individuals and families would consider themselves to be vulnerable that is, at risk, in jeopardy and so forth. And the extent to which vulnerability has become a label given to individuals and groups.

4. Institutionalising Vulnerability

Demonstrating a growing interest and concern about the vulnerable, in the UK, we also see an increasing use of the terms vulnerable and vulnerable groups in the development of policy. For example, the Housing Act 1996 (Section 218A), the ‘vulnerable victim’ is defined as someone who experiences repeat victimisation from other people, like antisocial behaviour. The Metropolitan Police Service have developed a Vulnerability Assessment Framework which explains that vulnerability can relate to vulnerable victims, witnesses, suspects or members of the public. The Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act was passed in 2006 and helped to further develop a criminal records check and database to assess people working with or volunteering to work with children and ‘vulnerable adults.’ Noticeably, criminal record checks had already been established to protect children (a designated vulnerable group themselves) and between 2002 and 2006 the number of people being checked had doubled and stood at ten million [14]. We also find ‘vulnerability’, in the government’s anti-terrorist Prevent Strategy, that impacts on many institutions, including universities who must be watchful regarding student extremism. Here, vulnerability is understood in terms of people who may adopt or be influenced by certain ideas [15]; rather than making subjective decisions themselves, they are being ‘radicalised.’

The Clergy have their own policy regarding vulnerability spelled out in their Safeguarding and Clergy Discipline Measure 2016. The Solicitors Regulatory Authority has guidance notes on ‘how to identify people who may be vulnerable’ and the ‘benefits of considering vulnerability’ helping those in the trade to become aware of the significance of vulnerability. Here we find the vulnerable include those on low incomes, who have a low level of literacy or have certain life experiences, like sufferings a bereavement [16].

At the level of international policies and practices the United Nations has a variety of documents, policies and practices explaining the importance of engaging with and supporting vulnerable groups and populations [17]. The Human Rights Act, an international convention to protect human rights that was incorporated into UK law in 1998 is also associated with the issue of vulnerability and the protection of the vulnerable. In their pamphlet on Eight reasons why the Human Rights Act makes the UK a better place, Amnesty International explained (point 2) that this act is ‘Protecting us at our most vulnerable.’ Points 3 and 4 discussed the protection of women from domestic violence and ‘making it safer to be gay’ [18].

Looking at the university sector we find that universities have a variety of policies regarding vulnerable students often based within ‘Student Wellbeing,’ with vulnerability relating to ‘academic, personal or practical issues.’ Some have their own email system for example, vulnerable-students@contacts.bham.ac.uk. The National Union of Students have a number of reports and initiatives that discuss vulnerability in a variety of contexts, including religious beliefs, crime, gambling, a living wage campaign, housing, fishing policies (that talks about vulnerable fish), drugs and educational funding.

The report looking at the experience of students with faith and beliefs is called the Isolation and Vulnerability Report. Within the report we find 30 mentions of the term ‘vulnerable’ and 57 uses of the term ‘vulnerability.’ The opening paragraph of the report explains that, ‘This research presents the findings of a nationwide survey on students’ experiences of isolation and vulnerability, with a particular focus on how students of faith and belief experience instances of isolation or vulnerability on campus’ [19].

In 2018, the National Union of Students (NUS) announced a partnership with Gamban—an app that helps users block access to online gambling. Here the claim was made that one-in-eight undergraduates had missed lectures or seminars because of gambling. The report explained that, ‘Many of these students are amongst the most vulnerable—and gambling addiction can be both a cause of and trigger for further mental health issues’ [20]. More action was ‘desperately’ needed to protect students from betting companies who were ‘preying on student vulnerabilities.’

The meaning of vulnerability is often taken for granted rather than defined and the term appears to come with a moral dimension that demands action and support. Different organisations—health, social care, the police and so on, use the term in differing ways, with for example social care relating more to poverty compared to the police and their focus upon victims of crime. However, even within this context, how the police think about crime has been altered by their wider adoption of the idea of vulnerability and vulnerable groups. While within social care and services the idea of poverty, a once stand-alone issue, has itself become a vulnerability label, with another vulnerable group—the poor—being constructed around this more therapeutic understanding of the fragile self. In this respect all of these organisations are helping to transform the way issues and individuals are understood and treated.

This list of just a fraction of the discussions and policies related to vulnerable people and groups gives a flavour of the vast numbers of people and array of organisations engaging with the vulnerable. Understanding or being aware of vulnerability has become a form of good practice. For some organisations like the NUS, vulnerability appears to be something of a starting point when relating to and developing services for students or initiating campaigns. For the police, engaging with the wellbeing of vulnerable people has become a ‘core’ purpose. At a number of levels and within a number of institutions being aware of the vulnerable and developing practices to engage with the vulnerable subject has become their raison d’être. Issues of safety, safeguarding, protection and prevention and the support necessarily implied through the label of vulnerability gives a regulatory dimension to many of these practices and issues. To be aware, to engage with and to protect the vulnerable is to be good.

5. A Theory of the Vulnerable Subject

The rise of vulnerability as a framework for understanding the nature of people can best be understood through the idea of diminished subjectivity. This concept, initially developed by sociologist Frank Furedi, carries two interconnected ideas—that of the diminished elite and of the diminished individual subject [6]. Related to both are discussions that developed in earlier decades of the twentieth century but came to fruition in the 1990s, discussions about the end or death of class, of politics, of left and right, of culture and of big ideas or metanarratives. Condensing these discussions, Furedi discussed the ‘loss of meaning,’ amongst the elite and indeed throughout Western society and its various institutions [21]. By the 1990s, socialism was ‘dead’ but as James Heartfield noted, without the left to oppose, the right appeared to implode [22], and, for Jacoby, this also meant that liberalism lost its backbone [23]. The confusion for many was the presumption that the end of the Cold War internationally and of the labour movement in the UK, there would be an inevitable rise of (Thatcherite) individualism. The reality, however, was far more dialectical and the collapse of a collective sentiment, organisations and interests (on both left and right) did not result in a confident sense of individualism and individual autonomy. As social beings, it turned out that the robust liberal individual was built upon a collective sense of meaning and existence. To his surprise and confusion, the modern day Robinson Crusoe, without a sense of nation, religion, class or human progress, soon found himself on the therapist’s couch [24].

Choosing his categories very carefully, Furedi argued that Western society had become individuated rather than individualised. Socialism was dead but liberal individualism was dying. The categories that helped to explain, inspire and frame much of life since the Enlightenment were being transformed, one of these was the very idea of the human subject—a subject that by 2018 would need a Gamban mobile app to help it not to gamble and miss lectures. This was a subject more prone to be done to than to be a doer—a subject at risk, rather than one that took risks—the vulnerable subject.

6. The Diminishing Subject

At a certain, practical level, for almost two hundred years, the idea of the robust subject was taken for granted. The competence and capacity of the individual was and to a large extent still is the basis of modern living. Without the adherence to contracts - of work, education, marriage, sales, legal and so on, the world would come to a standstill [22]. David Garland’s first book discussing the nature of English prison life in the nineteenth century, illustrates well the classical expectation of the individual subject to accept their punishment rather than being reformed by others [25]. Despite the harshness this could entail there was a respect for THE individual, the rational ‘man’ who made choices and could live with the consequences. This was John Stuart Mill’s responsible person, responsible not in that all their actions were good ones but that when they were not they knew that they were responsible for them—there was no need for a Gamban app—indeed the very idea of one would be seen as a degradation of what was the key to liberal society, your sense of personal capacity—your subjectivity [26].

Fast forward to the twentieth century and we find a beginning of the crisis of subjectivity in the discussion of ‘the crisis of man.’

“In the middle decades of the twentieth century, American intellectuals of manifold types, from disparate and even hostile groups, converged on a perception of danger. The world had entered a new crisis by 1933, the implications of which would echo for nearly three decades to follow—not just the crisis of the liberal state or capitalist economy generally and not only the imminent paroxysm of the political world system in world war. The threat was now to “man.” “Man” was in “crisis””.[27]

As yet, something only embodied within a section of the intelligentsia, there was an intertwining collapsing sense of human progress, of Western civilization—a sense of the ‘end of history’ and ultimately with the very idea of individual human capacity. The promises and excitement of a rational, dynamic, heavenly world that was made by and helped to make the liberal subject, were being dashed on collapsing economies, class conflict, with war and with a loss of meaning, discussed in the work of Emile Durkheim and especially Max Weber.

Mark Greif’s book about this crisis is focused upon literature and literary critics of the twentieth century. One such critic, Lionel Trilling summed up this sense of crisis in his discussion about the death of the novel. Unclear as to what had caused this apparent death, Trilling surmised that past writers like Shakespeare and Swift had often written about the depravity of human beings. But within a cultural climate that sensed a positive progression in society, these writings ‘could never prove their case against man’ and indeed, the very act of writing such magnificent works of fiction they actually enhanced this sense of human beauty and progress [27] (p. 106).

For Trilling, the novel was of such importance because, as he argued, ‘the novel…has been, of all literary forms, the most devoted to the celebration and investigation of the human will,’ this will he believed was dying [27] (p. 106). The challenge laid down by Trilling, to rediscover America and the human subject, inspired the likes of Ernest Hemmingway to write his great novel Old Man and the Sea in 1952.

Written as an attempt to rediscover or save the human subject, Hemmingway does a remarkable job in portraying the beauty of man in his struggle with a giant fish, but, Greif notes, he is only able to do this by stripping man from society, by portraying the man of maximum isolation—a Robinson Crusoe - in a basic struggle with nature. In many respects, Greif observes, this was not even the man of the mind but man as body [27] (p. 125). (Much as Mel Gibbon’s controversial attempt to celebrate the passion of the Christ, was drowned in the physicality rather than spirituality of Jesus’ death).

Hemmingway’s attempt to rescue man was a brave one but in this tale of man against nature, Greif rightly notes, ‘this leaves the question of the rest of the world,’ of society, of ‘civilisation’ [27] (p. 125). At the end of the novel, Hemmingway generates a Christian allegory, as the man struggles to shore with his cross-like mast draped over his shoulders. Rather than man, it turns out, we had to turn once again to God for salvation.

7. The ‘Death’ of the Subject

Fast forward again, this time to the early twenty first century and we find French philosopher Jean Baudrillard discussing The Spirit of Terrorism in which, in his usually abstract way, he explains that with 9/11, the terrorists did it, ‘but we wished for it’ [28]. In part, Baudrillard is explaining or perhaps expressing a more pervasive sense of Western self-loathing, one that the ‘Lost Generation’ of intellectuals had earlier grappled with. The crisis of ‘man’ had gone mainstream.

For Furedi and writers like Christopher Lasch, Zaki Laïdi and István Mészáros, the Cold War is understood to have been the fragile ever crumbling foundation that kept liberalism on a life support system—the ‘free world’ appearing to have some sense of credibility and meaning in comparison to what Ronald Reagan called the ‘evil empire.’ Once gone, however, the ‘West’ had to stand on its own two feet and soon found that the sins of the father were not only exposed but were all that could be seen.

The ‘fiction’ of the rational, progressive, robust human subject, something that as Heartfield notes had developed in the critical writings of Michel Foucault and others, was all that could be seen—the liberal subject, the active ‘man,’ the robust individual, was the author of the Holocaust; the collective/class subject the creator of the gulags.

More particularly, as Heartfield observed, the end of the cold war brought an end to the politics of left and right and to politics with meaning and substance. With no big ideas in politics we ended up with what he calls a process without a subject—a form of politics based on nothing more than the visionless management of the present—a kind of politics as HR—with little or no connection to a collective public or wider ideological basis of meaning and purpose. Politics no longer reflected the collective will of different sections of society but became a process expressed most clearly by its lack of an ‘ism’ and the empty numerical definition of the ‘third way’ [22] (p. 180).

Interconnected with the ‘death’ of politics and what Philip Reiff called the impoverishment of Western culture was the crisis of ‘man’ in terms of both humanity and also the individual human subject [29]. Alongside the diminished collective will we find, not the individualised robust individual but the individuated vulnerable subject. A diminished, degraded and damaged subject that was constructed over time helped by a new type of activism and anti-Enlightenment intellectualism.

Since the 1970s, Joel Best argues, American society has adopted a particular form of campaigning, specifically related to and developed through the idea of the victim [30]. All sides of politics he notes began to adopt this approach as a way to frame a winning argument—victims of crime being drawn against victims of welfare cuts, for example. Feminist ideas were seminal in this respect but were not alone in the new representation of groups as victims. From the perspective of diminished subjectivity, the victim is the logical creation of a society that is losing a positive sense of both collective and individual capacity. As politics and indeed society lose their relationship with an active public, society is itself increasingly experienced as something out there, not of our making, something that is being done to us not made by us. This operates at both an elite and individual level, developed through an elite that lacks ideas or a sense of direction, with a mass of people, a ‘silent majority’ [7] who fragment, becoming individuated and relatively powerless to forces in society they no longer understand.

Studying the moral panic around ‘senseless violence’ in the Netherlands, in 2008, Willem Schinkel astutely observed that in cases of serious violence it has become rare for the perpetrator to become known, rather, it was the victim that captured the imagination. Rather than society cohering, developing a collective sense of us and them around a ‘folk devil,’ it was now simply left with a scar, a sense of meaninglessness, a story of victimhood and yet another example of being ‘done to’ [31]. It was the vulnerable subject that now engaged the public sensibility.

Defining the period in the 1990s, Furedi called it the Culture of Fear. This was a culture, he argued that had a diminished sense of capacity, consequently, the energies of society rather than being used to change the world or to defend past gains were increasingly directed at ensuring everything is safe [6]—society was hunkering down. The anxious, directionless elite, unable to project into the future, engaged with the public sense of atomic fragility and a new form of governing developed attempting to do little more than ‘prevent harm.’ With few, if any, clear absolutes that could cohere society, safety became the new absolute, a prefix for everything from sex to play that meant it was good.

In these anxious times, ideas, institutions and norms began to change, no longer predicated upon the assumption of the robust liberal subject but of the vulnerable diminished subject—one that needed to be protected from an ever growing array of experiences. A consciousness of risk developed, predicated in part on a loss of public trust but driven by an elite self-loathing and abandonment of Enlightenment ideals. Almost everything, Furedi argues, became interpreted through a framework of risk management, while relationships and interactions were newly seen through the prism of abuse [6].

8. The Growth of Abuse

“Abuse is a moralised concept that represents the functional equivalent of sin. The association of abuse with victimisation emerged as an idea in the 1970s and became a defining dimension of human experienced in the 1980s. Since that time abuse has become normalised to the point that it serves as the cultural exemplar of evil. The narrative of abuse has facilitated the formation of an ideology of evil through which a variety of problems are given meaning.”[32]

Written in an easily accessible style, Furedi’s Culture of Fear is nevertheless vast in scope and follows the tradition of Christopher Lasch, who in his Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminished Expectations presented a similar picture of what he called a survivalist mentality [33]. For us, the usefulness of Furedi’s work in particular is the examination of ‘victimhood’ as a new identity and of the connected and growing concern with ‘abuse.’

For Furedi, a growing sense of and understanding of ‘risk’ developed in the 1980s often with reference to the environment [34] (in the ‘outside’ world) and was replicated by the growing preoccupation with ‘abuse’ or the ‘defilement’ of the individual (the inner world) [6] (p. 73). Abuse, in many respects, is the natural bedfellow of the vulnerable subject and, Furedi argues, it was normalised in the 1980s—the human (like the planet) as damaged goods—the human both degraded and degrading. Here we find a growing number of experiences explained through the idea of abuse, reflecting not the growth of harm but rather expressing the outlook of the new vulnerable subject. The abuse idea was helped by the focus upon it, from academics, policy makers and institutions, who discovered growing abuse or new forms of it.

Using Ngrams, we find, for example, the term ‘homophobic abuse’ barely existed until 1979 when the use of the term rose exponentially. Clearly violence and ill treatment of gay people existed and arguably existed far more before this date but the idea of this ill-treatment being framed through or in terms of ‘abuse’ was yet to develop2. Similar findings can be found with the term ‘domestic abuse’ and also ‘elder abuse’ the use of which rises exponentially from the late 1970s, with the early idea of ‘child abuse’ developing from the late 1960s.

For Furedi, there are a number of dimensions to this growth of ‘abuse’—the specific term abuse itself is important in terms of its connotations of defilement and contamination. Firstly, there is a tendency for academics and campaigners to search for or ‘discover’ abuse, both in the present and the past and within this a tendency to exaggerate the scale of it. This is assisted by a reinterpretation of experiences that would previously not have been thought about as abusive or at least not with the use of this particular term.

At the most extreme, Furedi notes, we find sociological theory developing that problematises everyday activities and reinterprets them through the prism of abuse. With a profound sense of vulnerability more and more activities and experiences are reinterpreted and presented in theory as forms of violence. Feminists like Catharine MacKinnon for example found that the extreme act of rape is difficult to distinguish from sexual intercourse [6] (p. 82). Similarly, Furedi notes that the logic of this approach was becoming relatively mainstream within sociology, with Anthony Giddens for example describing the ‘clear’ link between rape and murder of women which, ‘often contains the same core elements as non-violent heterosexual encounters, the subduing and conquest of the sexual object’ [6] (p. 84). As Furedi notes, reducing actions to core elements means we can find the most unlikely links, like between eating and cannibalism.

As such we find not a necessary rise in violence or harm but a tendency to discover this in many, even most forms of human relationships. A key problem being that it was no longer simply those on the right who were seeing humanity in this more degraded form but those associated with the left. As a result, there were few left to defend ‘man.’ Indeed, the very act of doing so could increasingly be interpreted as an act of abuse itself.

Examining the growth of the ‘cycle of abuse’ theory, a theory that predicts that once abused you will similarly go on to abuse others, Furedi notes that more radical voices have adopted this understanding, something that when aired by conservatives in terms of a ‘cycle of poverty’ has always been dismissed as deterministic and reactionary [6] (p. 87).

This way of understanding human experience, Furedi argues, is a new one. Victimhood appears to carry weight and often receives institutional recognition and support. At the very least the claim of victimhood seems difficult and at times impossible to question, despite its often subjective dimension. And it leaves scars. One aspect of the modern idea of abuse is that it is assumed to leave a lasting legacy. The legacy of abuse is also something that is understood to be carried on through future generations, almost genetically transferred, as ‘second generations of’ various forms of ‘abusive’ experiences emerge to claim the mantle of victimhood.

A key dimension of this development is the emergence of the victim label and in particular the development of a victim identity. This Furedi traces back initially to criminologists and other policy experts in the late 1960s who began to use the language of victimhood to define people’s experiences—the point being that the sense of ‘victimhood’ can only emerge if society defines your experiences in this way. Rather than having experienced a crime, you become a ‘victim of crime’ [6] (p. 98). Victimhood is not simply a thing it is an interpretation and a labelling and one that was emerging at the time when a ‘survivalist’ mentality was developing both within individuals and more importantly within Western elites, academics and institutions.

For us, the point of note or argument is to suggest that the rise of the victim and of ‘abuse’ emerged within a wider political and cultural climate, a culture of limits that lacked the intellectual and moral resources to carry society forward and consequently began to see the world through the prism of damage limitation. The natural subject for this time was not the robust, dynamic, risk taking liberal subject but the done to, at risk, vulnerable subject. A subject that was being increasingly ‘recognised,’ constructed and institutionalised through a new therapeutic etiquette and form of best practice. Consequently, groups in society, black people, women, homosexuals and also the working class, once seen as potential active allies in a political battle for change were reinterpreted as vulnerable victims. For Furedi, by the mid 1990s, a political climate had been created in which defending people from victimisation had ‘become everyone’s point of reference’ [6] (p. 103).

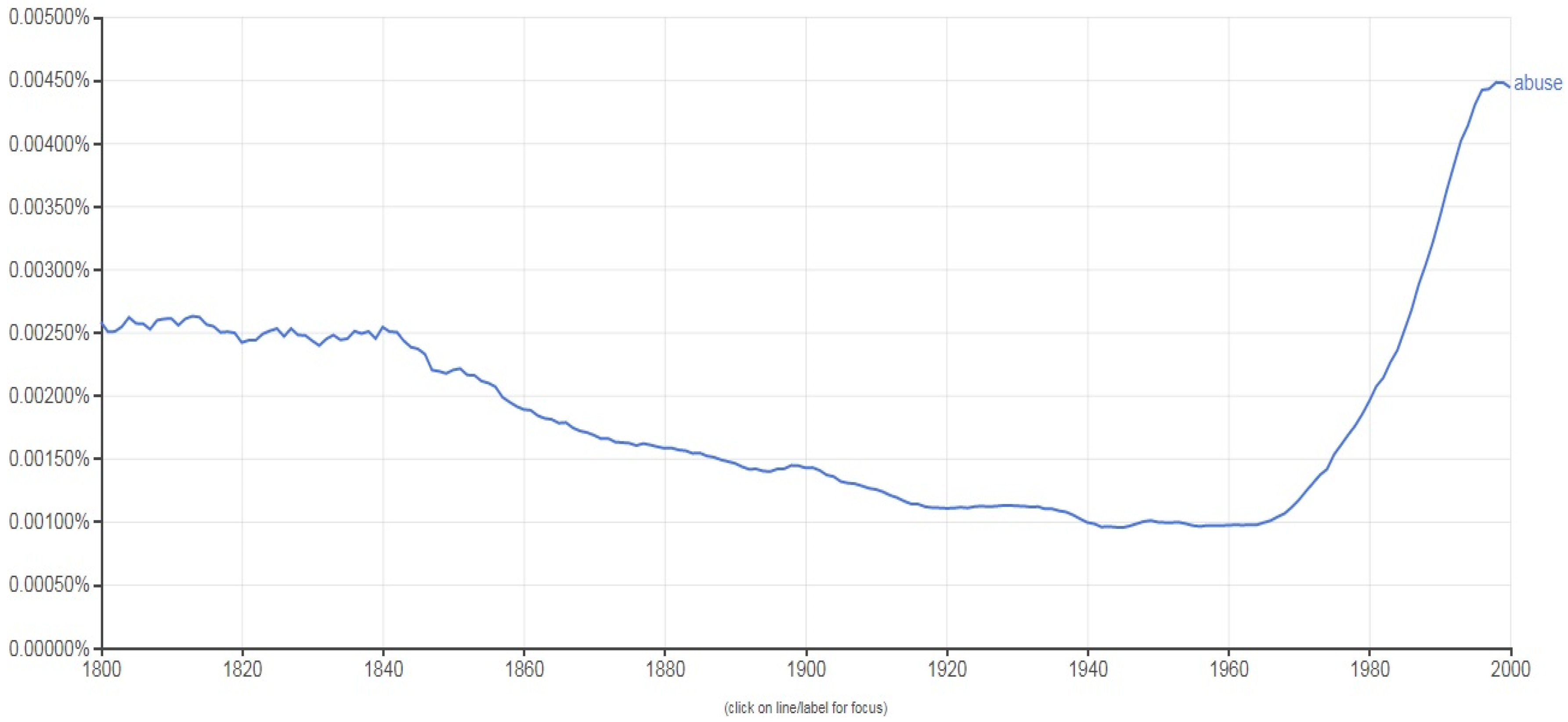

Discussing the meaning of the term abuse, Furedi notes that its importance is that it ‘evokes the notion of moral pollution,’ of being invaded, ‘to the point that those who have been polluted will never be the same again,’ something that, ‘affect[s] the spirit, identity and emotional integrity of the person.’ The use of the term abuse, in the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth century was interpreted through the grammar of morality, carrying the connotation of pollution, often referring to the pollution of the self through, for example, the perceived degradation of the act of masturbation [32] (pp. 54–55). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Abuse.

Interpreting the above Ngrams graph of the term abuse, what I would suggest we are witnessing in 1800 is the use of the term abuse that is carried by the language of Christian morality. This more traditional form of meaning continued to make sense of experiences and continued to have meaning until around 1840 when the modern transformation of society, the development and centrality of science and a more secular and liberal outlook was becoming more significant. In this respect, the declining use of the term abuse for the next 130 years reflected the decline of Christian morality and the rise of the modern liberal subject.

By around 1970 however, we see the rise and rise of the use of the term abuse, reflecting the decline of the liberal subject and the emergence of the vulnerable subject. This we would suggests can be understood as the formation of a new form of moralising about humanity as abusive and defiling (with the focus being less on self-abuse than the abuse of others [32]).

Just as the old Christian, moral language was losing its potential to limit individuals and society, a new etiquette or awareness of the harm of mankind broke onto the scene and became far more prevalent than the old moralisers of abuse ever did. It is within this context that a new master framework for engaging with the public developed around the idea of vulnerability and harm reduction.

9. The Vulnerable Subject in Law

“I consider that the striking of a fair balance between the demands of the general interest of the community (the community in this case being represented by weak and vulnerable people who claim that they are victims of anti-social behaviour which violates their rights) and the requirements of the protection of the defendant’s rights requires the scales to come down in favour of the protection of the community and of permitting the use of hearsay evidence in applications for anti-social behaviour orders.”[9] (p. 60)

In attempting to look at the importance of the vulnerable subject in law, policing and the criminal justice system, the above quote from Lord Hutton in 2002, gives a sense of how things have changed. The flexibility allowed to the justice system when dealing with anti-social behaviour (as opposed to murder, for example) allows the growing centrality of vulnerability to be more overtly expressed. Here for example, we find Hutton describe ‘the community’ being engaged by the criminal justice system, as represented by ‘weak and vulnerable people.’

Below we will look at certain changes in law and to discussions within legal theory, particularly about the harm principle that in various ways help to illustrate the growing importance of the vulnerable subject.

One such discussion relates to the problem of overcriminalisation, a process of proliferating and accelerating law making where an increasing array of experiences and behaviours are criminalised. The below quote from Andrew Ashworth gives a useful sense of this process and the accompanying concern by some legal theorists.

“The number of offences in English criminal law continues to grow year by year. Politicians, pressure groups, journalists and others often express themselves as if the creation of a new criminal offence is the natural or the only appropriate response to a particular event or series of events giving rise to social concern…There is little sense that the decision to introduce a new offence should only be made after certain conditions have been satisfied, little sense that making conduct criminal is a step of considerable social significance…[F]rom any principled viewpoint there are important issues-of how the criminal law ought to be shaped, of what its social significance should be, of when it should be used and when not-which are simply not being addressed in the majority of instances.”[35]

Various explanations are found to explain these developments and the focus, understandably, is often on opportunistic politicians and their use of ‘penal populism.’ But penal populism, can itself be seen as another example of the diminished (moral and political) subject, a lost sense of the capacity to either change the individual or to change society without the use of force [36]. For this paper, the central importance of overcriminalisation can best be understood as a product of the emerging vulnerable subject that needs ever more protections from the ever-obliging (post) modern criminal justice system.

10. Unprincipled Harm

By 1999, in his seminal paper, Bernard E. Harcourt was bemoaning what he called the Collapse of the Harm Principle. John Stuart Mill’s liberal principle had framed the limits for state interference in the lives of the individual. If there was no harm to another individual from a particular action, in the main, that action should not be regulated by law. This was a principle extended in the 1960s when liberal critics challenged the moralising aspect of laws against homosexuality, obscenity and prostitution—homosexuality harms no one and should, they argued, be decriminalised.

The harm principle, in theory, acted as a limiting principle to the enforcement of morality and thus freed the liberal subject from moralistic legal regulation. By the 1970s, in legal theory and to some extent in society, the liberals appeared to have won, with, for example, the decriminalisation of homosexuality and legalisation of hard-core pornography. But then something changed. Conservatives and feminists like Catharine MacKinnon changed the rules of the game and began to use the harm principle to criminalise increasing forms of ‘abusive’ and damaging behaviour. There was a triumph of the universalisation of harm, as Harcourt puts it and many more things began to be defined as harmful.

This did not mean that the moralists had won, rather, as Christopher Lasch argued, the moral right and their increasing reliance on ‘law and order’ reflected the collapse of moral ideas and arguments [37]. Now, the moralists dropped their morality and their moral arguments and instead of arguing that pornography or prostitution was morally wrong they simply argued that they were harmful. Rather than defending the moral subject, it was the vulnerable subject that became the heart (if not the soul) of their argument (and understanding).

These arguments, in an increasing number of areas of life, held sway and more things began to be criminalised. Harm, Harcourt noted, has become the principle argument for state intervention, rather than a barrier to it—the harm principle (from a liberal perspective) is therefore dead.

James Q Wilson, with his and George Kelling’s ‘broken windows’ theory helped to promote the idea that communities were vulnerable to a variety of nuisance behaviour that could bring down a neighbourhood and increase serious crime levels. Despite Wilson’s own moral background, he did not use moral arguments to criminalise public space, he talked about victims of crime and harm to defenceless and vulnerable communities.

MacKinnon, likewise, adopted the harm argument—pornography was harmful for the women involved in making it, harmful to the women who were assaulted by men who used it and harmful to women in general who had their second class position in society reinforced. This, an argument that had not existed in the 1960s, Harcourt argues, emerged in the 1970s and once again transformed the idea of harm into an argument for regulation and criminalisation. This time, rather than the ‘community’ being represented as vulnerable, it was women who were victims and in need of protection.

Conservatives and progressives, Harcourt concluded, are now making harm arguments. All sorts of harms that were previously seen as merely a nuisance are now seen as needing legal intervention. The focus today is no longer on whether certain actions cause harm, ‘it is about types of harm, the amount of harm and our willingness, as a society, to bear the harms’ [38].

11. Managing Emotions

Harcourt is unsure what to make of the collapse of the harm principle, trying in the end to suggest that this collapse may ‘ultimately be beneficial,’ something that ‘helps us realize that there is probably harm in most human activities’ [38] (p. 193). For the purpose of this paper, the conclusion is rather different and indeed the fact that Harcourt, in 1999, can end with this idea that most human activities probably cause harm is in itself something that could only make sense once the vulnerable subject had taken hold.

Within the criminal justice systems of most Western nations, this elevated sense of harm has been reflected in a variety of legal and policing practices and policies that increasingly engage with the ‘vulnerable public’ [36] (p. 45). Indeed, within politics, alongside the concern about vulnerability, vulnerable groups and vulnerable communities the ‘victim of crime’ has become increasingly central, from the 1970s in the USA and particularly from the 1990s in the UK. These changes have themselves been reflected within criminology, for example, in Jonathan Simon’s ‘governing through crime’ thesis where he examines the centrality of the crime victim for not only crime agencies but for institutions across American society. Perhaps the most influential criminologist, David Garland, has similarly focused on what he calls a ‘culture of control’ in the UK and US, usefully identifying the victim of crime and indeed the victim more generally as a symbolic figure, ‘a more representative character, whose experience is taken to be common and collective, rather than individual and atypical’ [39].

With the vulnerable subject at the heart of this development, the spiralling dimension of harm discussed by Harcourt can be identified within new laws and practices where vulnerability is increasingly conceptualised in relation to not only physical but to mental and emotional harm. And the role of the state increasingly comes to be that of protecting the vulnerable.

In Scotland, we can see this in a relatively early discussion about hate crime by the Association of Chief Police Officers in Scotland (ACPOS).

Having rarely discussed crimes through the prism of hate, in 2004 a Working Group on Hate Crime was established and a guidance manual on hate crime was written in 2010. The manual is noticeably therapeutic in its language, with the forward explaining that, ‘all crime can produce post-traumatic stress (PTS) in victims,’ but adding that, ‘it is recognised that PTS lasts longer in victims of hate crime’ [40]. The additional trauma suffered by victims of hate crime is central to the argument presented in the document about why hate crime needs to be a priority for the Scottish police service. At one level, the document can also be seen as representing and promoting a cultural shift towards an understanding that all victims of crime should be seen as vulnerable but also that some people are more vulnerable than others.

The report is particularly interesting in its use of evidence to prove the case that PTS can last for up to five years amongst victims of hate crime compared with other crimes. The one piece of evidence used to back up this claim is from America, relating to attacks on lesbian women and gay men. The vast majority of the attacks are clearly directed at the individuals due to their sexual orientation, some had, as the report explains, a surprising level of ‘physically and psychologically brutality’ [41]. The ‘brutal’ targeting of individuals for attack due to their sexual orientation can understandably have a significant impact upon an individual. However, moving from this one piece of research to then discuss all gay people as vulnerable and all hate crimes as doubly traumatising is problematic.

The relatively unquestioned idea of ‘hate crime’ today is interesting given the historical development of the term and the strong evidence of the politicised and indeed moralised nature of the concept. Paul Coleman for example traces the origin of the idea (and more particularly the idea of hate speech) to the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin and the desire to have the state determine correct and legally acceptable forms of speech, something that Western nations rejected at the time as illiberal and authoritarian [42]. In more recent times, the idea of ‘hate crime’ developed in the United States in the 1980s and, in part, due to their first amendment right to freedom of expression, it has also been strongly criticized as a basis for punishment [43]. In the UK, in relation to race and racism there have been various criticisms of the use of ‘hate crime’ laws and initiatives and indeed of the presumed trauma created by these crimes or what are often non-crimes or incidents [44]. For Adrian Hart, a major concern is the policing of young people in schools by teachers, who it is assumed are harmed by unpleasant and sometimes simply ‘incorrect’ comments and words and recorded as being involved in hateful behaviour, even at nursery school age.

Perhaps the most useful work examining the impact of hate crime legislation is that of James B. Jacobs and Kimberly Potter. Writing again about developments in America, they note that the majority of hate crimes are committed by teenagers. Many others involve poor young white and black (due to the colour-blind nature of hate crime legislation) young men involved in disputes or fights who shout an obscenity. Many of these incidents, they believe are questionable in terms of the definition of ‘hate.’ Their work also raises questions about the presumed and universal understanding of trauma experienced by those found guilty of so called ‘hate’ crimes [45].

Policing in the UK has moved away, somewhat, from a focus on property and physical violence and moved into new realms, of policing speech and of protecting people from emotional harm [35]. In Scotland, for example, a new law has been passed criminalising ‘coercive and controlling behaviour,’ types of behaviour that includes, ‘belittling’ and acting in a ‘demeaning’ way [46].

Discussing the growing concern with and the management of emotions, particularly in universities, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in their book The Coddling of the American Mind usefully examine the growing concept creep of the term trauma. Australian psychologist Nick Haslam, they note, has studied the changing use of terms like trauma, bullying and abuse and has noted that these concepts have both crept ‘downwards’ thus applying to less severe situations and also ‘outwards’ to incorporate new but conceptually related phenomena.

Pre the 1980s the term trauma for example, was used in psychology to relate to physical trauma, like a brain injury. In the eighties ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ became the first none physical trauma. This was understood to be caused by an ‘extraordinary and terrifying experience,’ ‘outside the range of usual human experience’ [47]. It was stressed in these early definitions that this was not based on a subjective standard but related to the most extreme of experiences like war, rape or torture. But by the early 2000, ‘the concept of “trauma” within parts of the therapeutic community had crept down so far that it included anything “experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful”’ that had a lasting effect on their well-being [47] (p. 26).

Key to this change for Haslam is the subjective dimension of this. For Lukianoff and Haidt, this is also of significance because individuals themselves, rather than just mental health professionals, started to think in these terms and use this concept of ‘trauma’ as a way to understand their experiences.

12. Some Thoughts and Conclusions about the Vulnerable Subject

Books like that of Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt are usefully attempting to grapple with what we have described here as the rise of the vulnerable subject, a subject or, diminished subject that has become the increasingly dominant framework for institutional practices and approaches regarding the management and regulation of human interactions. The presumption of human autonomy and the presumption of human capacity necessarily continues but as Ramsay has argued, this is now understood to be a vulnerable autonomy, something that is normalised and arguably encouraged by political, legal and cultural expectations and beliefs about what makes us human and indeed of what makes us good. Awareness of ones and one another’s vulnerability has, to a large extent, become a new form of ‘morality’ or at least a form of etiquette that informs us about how we should relate to each other and indeed about how we should understand our experiences. To some extent this has also changed the nature of law and of policing.

Within this context the presumption about the human condition is that we are vulnerable and that, as Harcourt reluctantly observed, we should recognise that perhaps all human interactions involve the possibility of harm. To be human, in this respect, is to be at risk. To be at risk means a transformation of the idea of freedom and in particular means a transformation in the relationship we have with freedom and regulation, with the latter increasingly understood to be the basis of our individual or individuated freedom.

As such, what we are witnessing is the construction of a new form of wellbeing state [48] and a presumption of the need to protect the vulnerable subject from an increasing array of harms that are understood to be potentially abusive, damaging and traumatising. This moves us away, as Michael Fitzpatrick has argued, from a relationship of the state with citizens, into a therapeutic relationship with clients or patients [49]. Rather than being citizens with wills and necessary freedoms we consequently move to a situation where people are conceptualized as in need of support, with their lives understood through the prism of risk management and support developed through the interventionist policies and practices all aimed to prevent harm to the vulnerable subject.

Work on the diminished subject suggests that there is a strong relationship between the depth of meaning that exists in and about society and the robust nature of individuals themselves. This is not simply a matter of ideas but equally about the extent to which society is collective or fragmented; something that is itself tightly bound up with the weakness or strength of meaning that gives rise to comradeship, communities or indeed to dynamic political organisations.

The argument here is that the declining sense of meaning generated by twentieth century society sporadically and then fundamentally gave rise to a diminished and degraded sense of humanity, opening the door to a new intellectual, cultural and then political elite with a diminished sense of human possibilities and a new culture of limits. This wider sense of limits encouraged a view of ‘man’ that was itself diminished, a vulnerable subject constantly at risk of harm. All activities, in both public and private and perhaps especially our relationships with one another come to be influenced by this dominant cultural form that helps to reinforce the idea of vulnerability3.

This is a very different subject to the one promoted by J.S. Mill. As Harcourt noted, Mill’s harm principle was not a standalone principle, it was not a technocratic or legalistic outlook but one based on a far larger and enlightened vision of ‘man’ as a ‘progressive being,’ based on a belief in ‘human flourishing.’ As Lionel Trilling pointed out, Mill’s time of writing was still a time when the case against ‘man’ had yet to be proven. Indeed, the case for ‘man’ was significant, and, Mill’s vision of ‘man’ was of a ‘noble and beautiful object of contemplation,’ uplifted by ‘high thoughts and elevated feelings’ [26].

These ‘elevated’ ideas of humanity, ones that would have been central to the ethos of university life, sound pompous and otherworldly today—naïve, arrogant or perhaps even dangerously deluded—an outlook that could lead to ‘othering,’ domination, oppression and the abuse of power.

One of Mill’s great liberal principles was that of tolerance—a perspective that encouraged the need for open debate, judgement and contestation of ideas and behaviours that were to be tolerated rather than regulated or criminalized—a basis for the belief in academic freedom and freedom of speech—indeed, a contestation of ideas was one of the ways in which humanity and individuals could elevate themselves. Today, like many other liberal principles, the meaning of tolerance has been transformed and now represents a demand that you withhold judgement and respect other people’s cultures and identities in case you cause offence. In many respects, tolerance is about an awareness of the potential harm that your words and ideas can have for the fragile feelings of the vulnerable subject [50].

The vulnerable subject is a more static subject, rather than a transforming one. One that has a more limited and fragile sense of self, that is threatened, rather than developed, by difficult experiences and indeed by difficult and challenging ideas. A diminished subject that experiences not only life but also knowledge as potentially harmful, abusive and traumatising, as something that needs to be restrained within our culture of limits.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fox, C. I Find that Offensive; Biteback Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Times Newspaper. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/stonewall-is-using-its-power-to-stifle-trans-debate-say-top-academics-dtswlcl0n (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Strossen, N. Hate: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech Not Censorship; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.G. A New Inquisition; Civitas: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dineen, T. Manufacturing Victims: What the Psychology Industry Is Doing to People; Robert Davies Publishing: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Furedi, F. Culture of Fear; Cassell: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. the Shadow of the Silent Majority; Semiotext: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, P. The Insecurity State: Vulnerable Autonomy and the Right to Security in the Criminal Law; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-41335762 (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- National Negro Health News. Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=LuYhAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA4-PA14&dq=%22vulnerable+groups%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjg1fXIrtXjAhX5QRUIHSpmDeA4FBDoAQg7MAQ#v=onepage&q=%22vulnerable%20groups%22&f=false (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- UN Report Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/COP/crpd_csp_2015_4.doc (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Department of Health: Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need 2000. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130404002518/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/Framework%20for%20the%20assessment%20of%20children%20in%20need%20and%20their%20families.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Appleton, J. The Case Against Vetting. Available online: http://www.statewatch.org/news/2006/oct/THE%20CASE%20AGAINST%20VETTING.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Prevent Duty Guidance. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prevent-duty-guidance (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Providing Services to People Who Are Vulnerable. Available online: http://www.sra.org.uk/risk/resources/vulnerable-people.page (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- More Protection, Focus on Helping Vulnerable Groups Key to Achieving 2030 Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/soc4856.doc.htm (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Eight Reasons Why the Human Rights Act Makes the UK a Better Place. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/eight-reasons-why-human-rights-act-has-made-uk-better-place-british-bill-of-rights (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Isolation and Vulnerability Report. Available online: https://www.nus.org.uk/PageFiles/12238/Isolation%20and%20Vulnerability%20Final%20Report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Has Gambling Affected You? Available online: https://www.nus.org.uk/en/news/has-gambling-affected-you/ (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- Furedi, F. Mythical Past Elusive Future; Pluto Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heartfield, J. ‘Death of the Subject’ Explained; Sheffield Hallam: Sheffield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jocoby, R. The End of Utopia: Politics and Culture in an Age of Apathy; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers, C.H. One Nation under Therapy; St Martins Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, D. Punishment and Welfare; Gower Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.S. On Liberty. 1859. Available online: https://www.utilitarianism.com/ol/one.html (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Greif, M. The Age of the Crisis of Man; Princeton University Press: Princepton, NJ, USA, 2015; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The Spirit of Terrorism; Verso: London, UK, 2002; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Reiff, P. The Triumph of the Therapeutic; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J. Random Violence; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel, W. Contexts of Anxiety: The Moral Panic over ‘Senseless Violence’ in the Netherlands. Curr. Sociol. 2008, 56, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furedi, F. Moral Crusades in an Age of Mistrust; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch, C. Culture of Narcissism; W.W. Norton Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society; Sage: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, L. Making the Modern Criminal Law; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Waiton, S. The Politics of Antisocial Behaviour: Amoral Panics; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch, C. Haven in a Heartless World; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt, B.E. The collapse of the harm principle. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 1999, 90, 109–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, D. Culture of Control; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hate Crimes Guidance Manual 2010. Available online: http://www.hatecrimescotland.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Association-of-Chief-Police-Officers-in-Scotland-Hate-Crime-Manual-2010.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Herek, G.M.; Cogan, J.; Gillis, R.J. Victim Experiences in Hate Crimes based on Sexual Orientation. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, P. CENSORED: How European “Hate Speech” Laws Threaten Freedom of Speech; Karios Publications: Middlesex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstenfeld, P.B. Smile When You Call Me That: The Problems with Punishing Hate Motivated Behavior. Behav. Sci. Law 1992, 10, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, A. That’s Racist: How the Regulation of Speech and Thought Divides Us All; Imprint Academic: Exeter, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, B.J.; Potter, K. Hate Crimes: Criminal Law & Identity Politics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow Herald 21 March 2017. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/opinion/15169707.iain-macwhirter-bill-on-emotional-abuse-is-fraught-with-danger/ (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Lukianoff, G.; Haidt, J. The Coddling of the American Mind; Penguin: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Waiton, S. The New Class and the Well-being State. In The Future of the Welfare State; Almqvist, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, M. The Tyranny of Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Furedi, F. On Tolerance; Continuum: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Google Ngrams is a database developed from a collection of books between 1500 and 2000 that allows a search for names or terms within these books. The calculation takes into account the volume of books at any one time so as to provide a map of the relative use of terms over time. Only when there are at least 40 books using the term in any one year does it appear in the graph. Note that Ngrams has been criticised for its lack of accuracy, in part due to its use of optical character recognition that can produce reading errors. Some of the books in Google Ngrams can be accessed via an Ngrams search, allowing for the texts themselves to be studied, thus allowing these terms to be situated and analysed in the context within which they were written. More than one term can be searched within the same graph, allowing a comparison between the use of terms and to demonstrate similarities in usage. For example, a search for vulnerable children and self esteem shows the greater use of the latter term but a very similar, indeed almost identical graph shape. For a discussion of the use of Ngrams as a research tool see https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5567/5535 (accessed on 29 August 2019). |

| 2 | This can be partly explained due to the relatively modern term homophobia but a similar result is found for ‘homosexual abuse,’ the point being that the term abuse was becoming more important and significant. |

| 3 | Almost every human activity comes with a risk but only recently has this sense of risk come to dominate and to often swamp the sense of possibility and potential of new developments and technologies. The internet, for example, is one area where we can see a growing tendency to treat this remarkable technology as problematic and dangerous, a new risk to be managed, demonstrated by the growing number of books written about online threats. See ‘Top ten books about the dangers of the web’. Available Online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/mar/16/top-10-books-about-the-dangers-of-the-web. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).