Abstract

Since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, much ado has been made about how racial anxiety fueled White vote choice for Donald Trump. Far less empirical attention has been paid to whether the 2016 election cycle triggered black anxieties and if those anxieties led blacks to reevaluate their communities’ standing relative to Latinos and immigrants. Employing data from the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey, we examine the extent to which race consciousness both coexists with black perceptions of Latinos and shapes black support for anti-immigrant legislation. Our results address how the conflation of Latino with undocumented immigrant may have activated a perceptional and policy backlash amongst black voters.

1. Introduction

While the 2016 victory of Republican Donald Trump over Democrat Hillary Clinton for the U.S. presidency has generated many conversations about the nature of white racial identity and its uses in electoral politics, the absence of conversations about black racial identity in postmortems on the Trump victory leave much unanswered about that election. This absence also limits scholarly inquiry into what the Trump Phenomenon means for contemporary conflicts in culturally and racially heterogeneous societies, especially societies coping with skirmishes over immigration policies. To overcome these limitations, we leverage national post-election survey data to explore the effects of black racial group consciousness on shaping black support for immigration policies and postures advocated by candidate Trump.

Scholarly focus on the import of white racial identity to the 2016 Trump victory is understandable, but it is also myopic. That Trump employed racial “dog whistle politics” [1] to clench the Republican nomination and the White House seemed to fly in the face of beliefs that Americans had turned a corner in race relations. On the heels of the two-term presidency of Barack Obama, the first person of African American identity to secure the Democratic presidential nomination or to win the White House, Trump’s dual victories seemed to signal a rolling back of American racial progress. Yet, as scholars have noted, Trump’s presidential win was not wholly unexpected given America’s sordid racial history [2]. The Trump win suggests that the Obama victories in 2008 and 2012 were an exception to the country’s racial history, not a rewriting of America’s racial rules. Moreover, Trump’s campaign relied on rehashed tropes of black criminality, minority law breakers, and white male victimization. For many Americans, Trump’s campaign slogan “Make America Great Again” seemed unnecessarily divisive and disqualified him from the presidency. However, for Trump’s core supporters the campaign slogan was more than a call to action—it was a simple truth and a repudiation of politically correct, culturally distant, Washington insiders of both parties. Furthermore, some actions of the Democratic Party and its presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton, seemed to work in Trump’s favor. Concerned about Trump’s ability to mobilize disaffected whites, the Democratic Party counterattacked by highlighting Clinton’s focus on the middle-class and her proposals to address economic anxiety, ongoing military interventions, trade imbalances, and access to affordable higher education and health care. Neither strategy neutralized Trump’s appeal as a “blue collar billionaire” nor undermined Trump’s effectiveness at giving voice to explicitly racial and sexist appeals long deemed socially undesirable. By election night, not only had Trump generated more favorable media coverage than did Clinton [3], Trump had also carried all sectors of white voters. White racial animus, white ascriptive identity, and frustration with perceived anti-white discrimination had motivated voter turnout and white support of Trump [4,5,6]. For many observers, the election postmortem was straightforward: Trump won by creating a campaign built on the racial fears of white Americans. That white supremacists seemed emboldened by Trump’s post-victory racial posturing, and by the Trump White House’s proclivity to grant employment and access to white supremacist sympathizers, only served to substantiate this belief. The veracity of this supposition notwithstanding, it nevertheless fails to account for the reactions of blacks who too heard Trump’s anti-Latino and anti-immigrant dog whistles.

Little is known therefore about whether Trump activated similar racialized concerns amongst blacks as he did amongst whites, or whether blacks, on a whole, held anti-immigrant sentiment at the same levels as did whites who avowed allegiance to Trump. While blacks did not vote for Donald Trump in great numbers, he did make some attempts to win their support. Though Trump’s efforts fell short, not voting for him does not mean that his “America first” message did not resonate with black voters. For instance, Trump spent time talking about black unemployment and its relationship to illegal immigration. He vowed to strengthen the Mexican border so that blacks could have a chance at jobs that illegal immigrants threatened to take away. In other ways, Trump connected the country’s economic stagnation and downturns in black socioeconomic mobility to the economic policies and border enforcement policies of the Obama Administration. Because Trump employed Mexicans as a euphemism for illegal immigrants and vice versa (to imply that all Mexicans in America were and are illegal immigrants), Trump’s message may have appealed to blacks harboring hostilities toward law breakers, Mexicans, Latinos, immigrants, illegal immigrants, or any combination of the above. Trump’s message may have also appealed to blacks who believed illegal immigration hampered the group’s socioeconomic progress. In short, there is much to learn about black response to the Trump Phenomenon: while blacks may have withheld votes from Trump due to his racialized campaign, it is possible that blacks were sympathetic to his message on immigration. To this end, we take a step back and focus on black attitude formation. While vote choice is considered the penultimate act of politics, it is necessary to understand the attitudinal foundations of vote choice. In the area of immigration, we know relatively little about black opinions. That blacks did not vote for Trump was to be expected, but we do not know whether his visions of an America overrun by (illegal) immigrants resonated with black voters in any way. That blacks may have held opinions similar to Trump’s opinions and still refused to vote for the candidate is the perceptual knot we confront.

In this paper, we explore the effects of black racial group consciousness, economic anxiety, and animus toward Latinos on black support for select immigration policy after the 2016 election cycle. Our research draws from intersecting theories on black linked fate, inter-minority politics, and on economic voting. If blacks do express racial group conscious and economic anxieties, does this lead them to disfavor immigration? Do blacks expressing high degrees of black linked fate embrace or oppose specific immigration policies? Do blacks conflate Latino with illegal? If so, does this change their perception of non-descript immigration policy? To what degree, if any, does anti-Latino sentiment and evaluations of the economy shape black perceptions about immigration? We argue not only that black racial and economic anxieties are important to understanding whether blacks will support or oppose immigration policies, but that neither high black linked fate nor high economic optimism could prevent blacks from taking anti-immigration postures in the presence of strong anti-Latino sentiment. Stated differently, we contend that narratives championing “inter-minority coalitions” may have overstated how black racial group consciousness inoculates against campaigns to support restrictive immigration policies. We investigate the extent to which Republican Donald Trump’s efforts to mobilize black anxieties in the service of reforming immigration policy did, metaphorically speaking, tie blacks in perceptual knots. It is without question that Trump attempted to cross-pressure blacks according to their national identity, group consciousness, partisanship, and economic perceptions. In short, Trump asked blacks to choose amongst themselves and between themselves and (racialized) Others. By disentangling these perceptual knots, we hope to account for the ways in which Black people form and use “us” versus “them” notions with respect to immigration.

Our study contributes to the study of racial identity politics in two distinct ways. First, we address black public opinion about immigration policy, an understudied area within public opinion research. In most cases, much of the literature about public support for immigration policy in America centers on white voters and their perceptions of racialized Others. Because whites are often treated as prototypical Americans, it is important to understand how black Americans, often deemed “outsiders” within their own country, think about themselves relative to immigrant groups. Second, we address the consequences of black linked fate in the context of contemporary high stakes inter-minority competition, an area of study within black politics research. Because black interests are often treated as synonymous with the “interests of native-born blacks”, it is important to understand when and how national identity shapes black opinions about immigration policy that will undoubtedly affect other black persons. Examining the complexity of identity politics and its attendant consequences, we seek to improve understanding of racial group consciousness in the domain of immigration.

2. Theories about Inter-Minority Politics and Their Limits

The relationship between blacks and immigrants, primarily Latinos, has been examined through two dominant lenses: coalition and/or competition. The waves of immigration since 1965 have changed the racial composition of the United States and brought immigrant groups into American cities, which were predominantly inhabited by black Americans. As a consequence, there was a great deal of intellectual attention focused on the relationships between blacks and other racial/ethnic communities. Those focused on the critical gains of the Civil Rights Movement and the politics of inclusion that movement embodied thought it was most likely that blacks and other groups would coalesce around a shared identity of racial oppression. This would lead to elite and mass organizing to advance mutual political interests. There is evidence that coalitions did arise in certain instances [7,8,9].

Still, the belief that coalitions would be the norm of minority politics has been called into question by scholars who found coalition to be contextual rather than a mainstay of inter-minority political organizing [8,10,11]. In circumstances where one group is the majority, coalitions are less attractive and less likely to occur because there is no incentive to join [12]. In most cases, political goods are limited and finite. As a consequence, a win for one group necessarily represents a loss for another group. Therefore, because of the first-past-the-post nature of zero-sum political contests, competition is more likely than coalition regardless of shared minority status [13,14,15,16].

Historically, African Americans have managed to log many successes at the local and state levels [17]. This is because blacks have had a longer history of organizing, have a range of indigenous groups to represent their interests, and an electoral apparatus that has aided their election of representatives at the local, state, and national levels [18]. While this representation has not necessarily brought blacks everything they have desired politically, there is a level of familiarity and comfort blacks have with American political institutions that is not necessarily true for other minority groups. As a consequence, though blacks are no longer the largest minority group in America, they remain the most well organized and politically incorporated. As such, whether groups choose to coalesce or compete to achieve their political ends, depends also on the relative strength of their potential partners. In the case of African Americans, there has not generally been a need to work with other groups. This may be changing, however, as Latino immigrants are abandoning traditional immigrant gateways and finding themselves in the majority-black South [19,20].

Latinos are the group most identified as potential coalition partners for Blacks. Yet, the Latino community is not monolithic and is comprised of native-born Americans, naturalized citizens, and undocumented immigrants. For a myriad of reasons, the voting eligibility of this population lags significantly behind its actual size [21,22]. Moreover, naturalized Latinos may not be mobilized to vote in the same way as blacks [23,24]. Therefore, blacks may be in a situation where they are smaller numerically but wield more political power because they have more voting eligible members and members mobilized to vote. Moreover, because most blacks live in the South, a more recent immigrant gateway, interracial coalitions are atypical. While seeing Latinos is a fact of life in the West and urban areas in the North, it has only been since the 1990s that Latinos have made inroads into the southern United States [19]. At the time the vast majority of Latino immigrants have come to the South, blacks have already been incorporated into the body politic. Despite some potential for interracial competition, there have been cases where blacks still oppose efforts to harm Latino immigrants and voters [19]. For example, in 2001, blacks were vocal in their opposition to Alabama state law HB 56 (known as the Beason–Hammon Alabama Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act). This legislation essentially turned law enforcement into quasi immigration officials and required public school employees to ascertain the immigration status of pupils before allowing admission [25,26]. Blacks witnessed similar efforts during 2012 in Mississippi with HB 488 which sought to make life so difficult for undocumented persons that they would leave the state altogether [27]. The Mississippi legislation empowered law enforcement officials to determine the immigration status of individuals they arrest; prevented undocumented persons from obtaining identification cards, driver’s licenses, or vehicle registrations; and required third party verification of immigration status in order to seek employment. In both states, blacks, immigrants, civil rights, and immigrant rights groups worked together to oppose these measures they considered draconian. While these are important moments of coalition are significant, it does not negate the fact that in the realm of politics most blacks operate logistically and geographically independent of other groups, including other minorities.

Although the theory of rainbow coalitions is intellectually appealing to voters and scholars alike, the theory often does not account for the highly contextual and uneven nature of America’s racial project [28,29,30]. Shared minority status does not translate into similar experiences with social stratification. Racial groups were and are sorted differently in the racial hierarchy with respect to whites as well as one another [29,31,32,33,34]. The occasional ruptures in minority relationships, therefore, are not unexpected as the aims and objectives of these groups are highly dependent on that group’s place in the American racial hierarchy. Minority group status has the potential to bring groups together as well as tear them apart [35]. Given that, beyond similar experiences of exclusion, it is unclear if blacks currently see a common cause with immigrant groups because black opinion on contemporary immigration is understudied. Consequently, what we know about the reach and substance of contemporary inter-minority politics is far from settled.

3. Black Public Opinion on Immigration

3.1. A History of Black Support and Opposition

While blacks may only see immigrants as political partners in limited circumstances, this does not necessarily reflect how blacks have viewed immigrants or immigration policy [36]. In general, blacks tend to exhibit warmer opinions toward immigrants than native-born whites [37]. In fact, when examining the role of realistic group conflict (RGC) on black opinions on immigrant groups, Thornton and Mizuno [37] find that when blacks perceive economic competition with immigrants, they become more distant from whites. This suggests blacks may view whites as the source of economic competition not immigrants [38,39]. What is more, recent survey evidence has shown that blacks generally did not favor the harsh measures the 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump endorsed, such as deportations and the building of a new wall between the U.S. and Mexico. For example, the 2016 African American Voter Poll, fielded on the eve of the November 2016 election by the African American Research Collaborative, found that immigration was not cited as one of the “most important issues the next president should address”. This finding held when there was specific mention of the black community and when there was not. In both instances, when the black community was mentioned and when it was not, the most important issue for blacks was jobs. With respect to immigration, a clear majority of blacks favored the DREAM Act and comprehensive immigration reform. Likewise, 83% of sampled black voters evaluated relationships between their group and Hispanics as “very good” to “somewhat good”; similarly, 80% evaluated relationships between blacks and Asians as “very good” to “somewhat good”. These findings suggest blacks would be less interested in more punitive immigration policies.

Despite various arguments why blacks should be restrictionist in their immigration preferences, blacks have not strongly supported efforts to curb immigration to the U.S. [40]. This is not to say that blacks historically supported efforts to encourage immigration either. For example, from the nineteenth century well into the twentieth century, blacks did not necessarily express positive opinions about immigrants and, in many instances, some black newspapers freely disparaged immigrants from all parts of the world [41]. Yet, at moments when the United States became more restrictionist in their policy and singled out groups for exclusion, as with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, blacks were highly critical of U.S. immigration policy which they critiqued for being racist and hypocritical [42]. This criticism of U.S. immigration policy continued throughout the twentieth century as the U.S. frequently took an aggressive posture toward immigrants from non-European countries [43]. Moreover, generally speaking, immigration does not rank amongst blacks’ top issues [44] (Pew Center 2010). Prior to 1965, it is very clear why immigration would not be at the fore of a black political agenda. The issue had not moved to the forefront nearly five decades later as blacks stopped being the largest minority group in the United States and as immigration became more central to the consciousness of the American public. According to a Gallup poll from July 2013, healthcare and unemployment were the main issues that blacks felt were of primary importance for their racial group. In addition, blacks are the most dissatisfied segment of Americans as it relates to their treatment in American society; many blacks feel it is necessary to have the U.S. government act to improve the social and economic well-being of Black people [45]. That these political aspirations and economic anxieties influenced black opinions with respect to immigration cannot be discounted.

In cases where blacks feel economic threat from immigrants, they are less positive in their assessments of immigrants. Claudine Gay [10] shows that anti-immigrant sentiment is not simply about relative group size, but about one group’s economic well-being relative to another. In examining black attitudes toward Latinos, Gay finds that those blacks who perceive Latinos as wielding more economic resources relative to their group are more likely to express racially prejudicial attitudes toward this group. Thus, as these groups may have common material interests and similar standing in the racial hierarchy relative to whites, their perceived competition with one another may impede coalition development at the mass level [10]. While these findings are important, the role of economic competition is far from uniform [10]. For example, Nteta [46] demonstrates that class membership moderates black evaluations of immigration. Nteta [46] finds evidence that blacks are self-interested, but this varies across class status. Working-class blacks who believed they, or a loved one, lost a job to an immigrant were more supportive of federal intervention into workplace enforcement. Similarly, being unemployed was a significant predictor of black support for a constitutional redefinition of citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants born in the United States. Given the increased likelihood of working-class blacks to be in competition with immigrants for similar types of employment, black preferences for immigration restriction are rational. These findings of the relationship between class and black attitudes, is far from settled, however.

In other cases, scholars do not find that economic factors matter when blacks evaluate immigrant groups [47]. In the work of Cummings and Lambert [48] the authors find evidence that black attitudes toward Latino and Asian Americans are similar to whites. More importantly, the authors find that blacks who have negative opinions of other blacks are more likely to have negative opinions of immigrant groups. Kinder and Kam [49] find that ethnocentrism, a generalized prejudice characterized by ingroup solidarity and outgroup hostility, has an effect on black opinion on immigration. Blacks who had a more ethnocentric orientation also trended more conservative in their immigration policy preferences. While blacks favored policies such as fair employment, affirmative action, and government assistance for their groups well-being, they opposed affirmative action in hiring practices, job training and educational assistance for Latinos or Asians [49] (p. 204). Masuoka and Junn [50] explored black differentiation of immigrants by performing an experiment where blacks and other respondents were primed to think about particular immigrants (i.e., Asian or Latino) when considering immigration policies. Respondents were not given a particular stereotype because the goal was to see whether the relative status of an immigrant group would influence changes in immigration opinion. For example, the authors expected Asian immigrants, with no prompting, would be perceived as higher status because they are generally considered to be the “model minority” [29,51]. When blacks were in the control group and no particular group was pictured, they favored more restrictionist policies. By comparison, when they were primed to picture a specific group, either Asian or Latino, blacks were less likely to favor more restrictionist immigration policies. Their findings suggest “racial priming can encourage positive attitudes toward immigrants” [50] (p. 218). Nevertheless, the authors also find that, among African Americans, “stricter perceptions of group boundaries influenced support for making English the official language of the United States but did not significantly affect support for a policy denying social services to all immigrants” [50] (p. 154–55). Taken together, these findings demonstrate both the complex nature of public opinion on immigration and the impact of racial and national identity on opinion about immigration policies [50].

3.2. The Convergence of Race and National Identity

The aforementioned opposing viewpoints in the literature also demonstrate the ways in which race can expand and restrict one’s notion of inclusion. Because blacks are primarily concerned with the interests of their group as much of the literature in black politics demonstrate [52,53,54,55,56], this does not mean that blacks do not care about others. Rather, it means that the needs of blacks as a group come first in the minds of individual blacks as they assess most issues. Immigration is no exception. As a consequence, it is not incongruous to see blacks who think immigration “is good for the country,” but do not necessarily want to see the numbers of immigrants increased. Still, as scholars show, the heterogeneity in black opinion on immigration cannot be overstated. Perhaps what is driving these differences in scholarly findings is how the authors measure competition, economic well-being, anti-immigrant attitudes and opposition to immigration policies [57]. Despite these differences in measurement, the import of linked fate seems to diminish in the face of class and intraracial pressures [10,46,58,59]. This may be due to the myriad ways in which individual members of the black community develop their racial consciousness, or it may be due to the ways in which racial consciousness is tied to other attitudes. To that, while the means of one’s racial socialization can vary, it is also expected that one’s identification with other parts of their identity, such as national attachment, can influence their opinion on immigration [60].

The nuances of national attachment have long fascinated scholars. In particular, scholars have recognized that strong expressions of American patriotism could correlate with support for inegalitarian policies. While national attachments such as nativism and patriotism are generally considered two sides of the same coin, they are not equivalent. Nativism is a type of chauvinistic national identity where the world is partitioned into an “us” versus “them” and outsiders, particularly those who are not white-skinned, are often treated as threats to national cohesion [49,61,62,63]. Patriotism, on the other hand, is considered a positive affirmation of national identity that does not rely on the derogation of others and is therefore more open to the inclusion of newcomers [62]. Unfortunately, much of the extant literature on national identity is limited in its application to black people. To fill this gap, Mangum and Block [64] use Social Identity Theory to understand the influence of American identity on how individuals see immigrants. They argue that those individuals who espouse a strong national identity and view immigrants as wanting to become integrated into American society will see immigrants as in-group members. On the other hand, those who see immigrants as outgroup members will favor anti-immigrant policies. The authors delineate five dimensions of American identity: being born in the USA; being truly American; American patriotism; sociocultural threat; and sociopolitical threat. They find that each dimension of American identity leads individuals to favor legal immigration and support policies to suppress illegal immigration. What this work demonstrates is that American identity can supersede all other considerations and lead individuals who identify as American to see immigrants as perpetual outsiders who are incompatible with the prototypical American. The only mitigating factor was a high degree of political knowledge, with higher knowledge respondents being more discerning about what messages they accept [65]. Still, the larger takeaway is that American identity is compatible with more disapproval of immigration.

Though Mangum and Block [64] help us to understand the importance of national identity, they do not address the different dimensions of national attachment or the ways in which national identity may be expressed differently by different racial groups. Informed by Social Identity Theory, Carter and Pérez [61] test various types of national attachment (i.e., national pride, nationalism, and nativism) to gauge whether blacks and whites are different in their expressions of national identity. Additionally, the authors examine whether racial group consciousness increases xenophobia toward different outgroups. The authors find that whites who are high identifiers with the nation also display a high racial identity; the inverse is true for blacks whose national identity and racial consciousness move in opposite directions. In addition, whites who express a more nativist political orientation are likely to hold negative evaluations of all immigrant groups except white immigrants. Likewise, strong racial identification and cultural concerns increase negative opinions of all non-white immigrant groups. For blacks, strong national pride is not associated with the derogation of foreigners. In fact, “greater national pride among [b]lacks lessens hostility toward each immigrant group,” regardless of race of immigrant [61] (p. 507). The authors also find that nativism increased black hostility to all immigrant groups regardless of their national origins. Racial identity was unrelated to black xenophobia, but concerns about employment prospects heightened their negative feelings toward immigrant groups. Taken together, Carter and Pérez [61] demonstrate that national attachment is a significant identity, one which informs opinions in the domain of immigration, but that race informs how different groups attach to the nation. What is more, blacks and whites do not necessarily have the same view of immigrant groups. In the case of whites, opposition to immigration is focused on American culture and fears that immigrants may threaten their cultural heritage. Blacks are far less concerned about culture, but more about their ability to thrive economically in the presence of immigrants.

In all of these cases, however, it has been found that a black racial consciousness tempers the effects of national identity such that blacks are more sensitive to immigrant groups. Many assume this relationship to be static. Yet, there is evidence that blacks also have reservations about immigration. That is, while blacks view immigrants more warmly than they do white Americans, but it is also the case that blacks see themselves in competition with immigrants [19,37,40,66,67]. This trepidation is informed by their experience with racial discrimination and exclusion from the public sphere [42,68,69]. It is also the case that blacks’ activism during the Civil Rights Movement, in part, helped produce the Immigration and Nationality Act (1965) and blacks have never mobilized around anti-immigrant campaigns [70,71]. But all of these works characterize the political climate before the election of Donald Trump. Hence, it is unclear whether black attachment to an American national identity will function as it did prior to the ascendancy of Donald Trump: In a post-Trump political context rife with various racial messages, blacks with strong attachments to an American national identity could oppose or endorse restrictive postures toward immigrants.

3.3. The Curious Case of the 2016 Presidential Campaign of Donald Trump

The 2016 Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, espoused a racialized view of American identity which largely presented white males as victims of government overreach, lax immigration policies, and faulty economic policies. Trump castigated immigrants for jeopardizing white livelihood (by taking jobs away from whites) and for threatening white lives (by engaging in criminal activity). Donald Trump focused on Mexico as America’s principal opponent in the fight against illegal immigration. In multiple speeches, Trump singled out crimes committed by undocumented Mexicans and Mexican gang members as the need for building the border wall. He also cited lax Mexican border enforcement and accused the nation of essentially dumping the dregs of their society on American soil to wreak havoc on America and her citizens. In Trump’s formulation, Mexicans are illegal immigrants and illegal immigrants are Mexicans. Furthermore, in Trump’s formulation, illegal (Mexican) immigrants are not simply a threat to the sociocultural and material well-being of Americans, illegal immigrants also pose a violent threat to Americans due to the former’s appetite for rape and murder.

Trump outlined his thoughts about immigrants and immigration when launching his bid for the 2016 Republican nomination on 16 June, 2015 at Trump Tower in New York City. In that speech, Trump mentioned Mexico thirteen times. In each case, he talked about Mexico, the nation and its people, as either being a poor trading partner or usurper of American largesse. When talking about Mexican people directly, he characterized those coming to the United States as “not the right people.” He also said the following:

When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you.

They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.

Neither Trump’s anti-Mexican rhetoric nor Trump’s fusion of illegal immigrant with Latino was unprecedented or unexpected [72,73].

Many observers however were surprised that Trump maintained his anti-immigrant posture throughout the presidential election cycle and well into his presidency. For example, in spring 2018 in West Virginia, Trump said "And remember my opening remarks at Trump Tower, when I opened. Everybody said, ‘Oh, he was so tough,’ and I used the word ‘rape.’ And yesterday, it came out where, this journey coming up, women are raped at levels that nobody has ever seen before. They don’t want to mention that” [74]. Without offering any evidence, Trump doubled down on his belief that undocumented men are generally rapists. Though in this iteration of the allegation, it is undocumented women who are the victims. Still, in that same speech Trump also said that the U.S. immigration system was a “lottery” being abused by countries that are sending undesirable citizens. He claimed, “With us, it’s a lottery system—pick them out—a lottery system. You can imagine what those countries put into the system. They’re not putting their good ones” [75]. While Trump does not explicitly mention Mexico in his speech, it was implied. Given the connection Trump made between Mexico and illegal immigration during his 2016 presidential campaign, it is more likely than not that Americans may have been conflating illegal immigration with Latinos more generally and Mexican people most specifically. That President Trump continues, as of October 2018, to pivot to anti-Mexican talking points when discussing immigration is unsurprising. Polls from 2016 revealed that Trump’s hardline stances on immigration helped him clench the presidential election.

The success of Trump’s offensive tropes about Mexicans and about undocumented immigrants, in part, can be attributed to white racial resentment [76,77], a belief among whites that “blacks do not try hard enough to overcome the difficulties they face, and they take what they have not earned” [77] (p. 105). This resentment is expressed as opposition to policies that cite blacks as the primary beneficiaries. In general, the opposition is made on non-racial grounds and appears as a type of “principled” individualism that disfavors government intervention to address issues, such as poverty, which are thought to be about individual failings rather than larger systemic issues [78]. While there are disagreements over the attribution of white opposition to race-based policies, it is clear that race motivated white voters’ decision to cast ballots for Donald Trump. Klinkner [6] found a significant relationship between white beliefs that Obama was a Muslim and votes for Trump. Similarly, Fording and Schram [79] found that low information voters were more susceptible to Trump’s racial messages and were more likely to vote for him if they held anti-black views and were opposed to Mexican immigration and Muslims. This racial component is also there when examining the vote choices of white women. Frasure-Yokley [4] and Tien [6] both show white women used their race, not their gender, when determining their vote choice. This is part of a larger pattern in white women’s voting that has seen this portion of the electorate vote for white, male, Republican candidates more often than not [2]. In the case of white voters, regardless of gender identity, race was a motivating factor in their selection of Donald Trump in 2016.

That white racial resentment mattered to the 2016 white vote for Trump leaves many questions unanswered about the reactions of blacks to Trump’s anti-Latino presidential campaign. While a majority of blacks did not vote for Trump, it is unclear if Trump’s claims regarding illegal immigration were persuasive. It could be the case that black racial anxieties were raised in this highly fraught racial context. In one attempt to woo black voters, Donald Trump held a campaign event in Michigan in August 2016. He asked blacks to try “something new” by voting for him. In that same speech, however, Trump said blacks were on the verge of “becoming refugees in their own country” because his opposition ignored black needs by giving illegal immigrants jobs rather than black citizens. He said:

By contrast, the one thing every item in Hillary Clinton’s agenda has in common is that it takes jobs and opportunities from African-American workers. Her support for open borders. Her fierce opposition to school choice. Her plan to massively raise taxes on small businesses. Her opposition to American energy. And her record of giving our jobs away to other countries. America must reject the bigotry of Hillary Clinton who sees communities of color only as votes, not as human beings worthy of a better future. Hillary Clinton would rather provide a job to a refugee from overseas than to give that job to unemployed African-American youth in cities like Detroit who have become refugees in their own country. It is time to get our country back to work, and that includes an all-out effort to help young African-Americans get the good-paying jobs they deserve.

That Trump’s outreach efforts toward blacks mirrored the efforts employed by Republican presidential candidates of the late twentieth century do not make those efforts any less consequential. Neither does the fact that Trump’s percentage of the black vote hovered around eight percent (8%), a figure not dissimilar from the average garnered by post-Great Society Republican presidential candidates. We contend that the significance of Trump’s outreach efforts rests not in whether a majority of blacks voted for him, but in how Trump’s rhetoric attempted to leverage black identity politics by agitating black socioeconomic aspirations, black concerns about their relationship with the Democratic Party, and black economic insecurity. Additionally, we assert that post-mortems on the 2016 presidential election which focus on vote shares alone devalue inquiries about whether blacks disagreed wholly with Trump’s message, with his delivery, with his candidacy, or with any or all of the above.

We submit that treatment of Trump’s potential impact on black voters and black public opinion on immigration must address the interplay between black racial identity, local context, and economic perceptions. Namely, while we acknowledge that prior scholarship has found a consistent link between economic insecurity and opposition to immigration reform [10,80,81,82], we contend that racialized economic insecurity may have mattered for blacks in particular locales as much as it mattered for whites across the nation. Put differently, we maintain that black economic perceptions mattered to the extent that immigrants are viewed as a threat to black livelihood (rather than as a threat to white livelihood) and mattered only as much as individuals were receptive to Donald Trump’s message. Because ideological predisposition and context affects receptiveness to messages, we acknowledge that the effects of neighborhood racial and socioeconomic composition on political attitudes are largely different for whites and non-whites. We further acknowledge that residential political and racial segregation have made it more likely than not that Americans misdiagnose neighborhood quality, overestimate the number of racial/ethnic minorities that live in their local communities and the nation [83], and misperceive the abilities and behavior of outgroup members [14]. Consequently, given blacks’ economic vulnerability coupled with higher incidences of racial isolation, it could be the case that Trump’s message may have gotten through to some blacks although reception of the message did not translate into actual votes [39,46]. In other words, we argue native-born blacks, especially those with strong attachments to American identity and living in economically depressed neighborhoods heavily populated with Latinos, could have been persuaded that Trump’s “America First” message meant that he would prioritize natives over immigrants and prioritize non-Hispanic blacks over Hispanic immigrants. We seek therefore to understand the role of anti-Latino resentment in shaping black preferences toward immigration policy reforms, to understand whether blacks expressed the types of racial opinions about immigrants normally found expressed amongst whites, and to understand whether black antipathy toward Latinos affected their posture toward illegal immigrants.

4. Hypotheses, Research Design, and Data

4.1. Hypotheses

We test the following seven hypotheses about the relationship between the dependent variables and black linked fate, anti-Latino attitudes, immigrant heritage, and registration status. First, we hypothesize that high levels of black linked fate will be negatively associated with support for the anti-immigrant posture on the 2016 immigration policy measures. Specifically, blacks with high black linked fate will be less likely to support deportation for immigrants who break the law than will blacks with no linked fate (Hypothesis 1a), less likely to support increased funding for border security than will blacks with no linked fate (Hypothesis 1b), less likely to agree with the statement that immigrants take from native-born residents (Hypothesis 1c), and more likely to report that it is very important for political activity to address the challenges of black undocumented immigrants (Hypothesis 1d). Second, we contend that strong agreement with anti-Latino statements regarding the ethnic group’s social conformity and cultural integration will be positively associated with black support for the explicit and implicit anti-immigrant policy measures. Specifically, we hypothesize that blacks who strongly agree with the notion that Latinos are socially deviant will be more likely than other blacks to support deportation, but blacks who strongly agree with the notion that Latinos are culturally isolated will be neither more likely nor less likely to support deportation (Hypothesis 2a); that blacks who strongly agree with the notion that Latinos are socially deviant and culturally isolated will be more likely than blacks who strongly disagree to support increased funding for border security (Hypothesis 2b); that blacks with strong anti-Latino sentiment will be more likely than blacks with weak anti-Latino sentiment to agree with the statement that immigrants take from native residents (Hypothesis 2c); and that blacks who strongly agree with the notion that Latinos are socially deviant and culturally isolated will be less likely to support the position that it is important to address the challenges of black undocumented immigrants (Hypothesis 2d). Third, we hypothesize that registered blacks will be more likely than non-registered blacks to support the anti-immigrant policy position. Fourth, we hypothesize that blacks self-identifying as being primarily rooted in American heritage will be more likely than blacks self-identifying as being primarily rooted in immigrant heritage to take the anti-immigrant position on the four policy measures. Fifth, we hypothesize that blacks living in economically distressed zip codes will be more likely than blacks living in economically vibrant zip codes to take the anti-immigrant position on the four policy measures. Six, we hypothesize that perceptions about the proportion of Latinos residing in a neighborhood will affect support the four policy measures, with higher proportions leading to an increased likelihood of supporting the anti-immigrant position on the four policy measures. Seven, we hypothesize that blacks with high levels of economic anxiety will be more likely than blacks with high levels of economic optimism to agree with the anti-immigrant position on the four policy measures.

4.2. Data and Methods

To measure black anti-Latino attitudes and anti-immigrant attitudes, we turn to the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS). The extensive CMPS questionnaire and the large black sample size enable us to conduct a robust evaluation of the sociodemographic and attitudinal variables determining black support for restrictive immigration policy [84]. The 2016 CMPS was an online self-administered multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, post-election survey of 10,145 adult Americans fielded from 3 December, 2016 to 15 February, 2017. The data for Latino, black, Asian, and whites (non-Hispanic) are weighted within each racial group to match the adult population in the 2015 Census American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year data file. A post-stratification raking algorithm was used to balance each category within 1 percent of the ACS estimates. For the purposes of our study, we focus on the weighted sample of 3102 blacks (2002 registered to vote and 1100 not-registered). Respondents answered questions about perceptions about immigrants, policy positions on select immigration reform measures, perceptions about Latinos, perceptions of linked fate, attitudes toward law enforcement, immigrant heritage, racial consciousness, and ideology. Respondents also answered standard demographic questions and questions about the racial/ethnic composition of their neighborhoods.

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

We utilize four questions from the 2016 CMPS to serve as our dependent variables. The first question assesses the degree to which blacks agree or disagree with stringent law enforcement procedures affecting immigrant populations living in the United States (Deport Law Breakers): “Immigrants who break the law should be forced to leave the U.S. and return to their countries of origin.” The response options were “strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree”. The second question assesses black belief in the adequacy of federal funding levels for preventing unlawful entry into the United States (Border Funding) and embeds an experimental design to ascertain whether the explicit cue of “immigrant” or “undocumented” changes support. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate whether you would like to see federal spending increased or decreased or stay the same: Tightening border security to prevent [illegal/undocumented] immigration.” Respondents were randomly assigned to receive the “illegal” or the “undocumented” cue. This experimental treatment allows us to test the differential effects of each cue condition on federal spending directly linked to immigration policy. The third question measures black susceptibility to support nativist actions or postures taken by individuals, states, or organizations (Immigrants Take): “Immigrants take jobs, housing, and healthcare away from people who were born in the U.S.” The response options were “strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree”. The fourth question measures support for exclusionary postures within the black advocacy community that affect immigrants with shared ascriptive characteristics (Support Black Immigrants): “How important is it for Blacks to address the challenges of Black undocumented immigrants?” The response options were “not important at all, somewhat important, very important”. The first two dependent variables approximate black support for explicit anti-immigrant policy, while the latter two dependent variables approximate black support for implicit anti-immigrant policy. Here we use implicit to mean support of an exclusionary posture or practice regarding immigrants which may lead to the enactment of discriminatory actions, and we use explicit to mean support for restrictive policies designed to affect immigration to America.

4.2.2. Independent Variables

Our primary independent variable of interest is a measure of anti-Latino sentiment. We use seven questions measuring agreement/disagreement with offensive and non-offensive stereotypical depictions of Latinos to generate our measure of black anti-Latino sentiment. Respondents answered the following: “Generation after generation Latinos continue to have strong attachments to their country of origin.”; “Over the past few years, Latinos have gotten more economically than they deserve.”; “Most Latinos in our country today want to adopt American customs and way of life.”; “Latinos don’t value education and often times end up dropping out of high school.”; “The distinct nature of Latino culture and traditions enriches American culture for the better.”; “Latinos rely on social welfare programs to maintain their families.”; and “Even after several generations in America, Latinos continue to have a tendency to get involved in gangs and organized crime.” The response option was the standard four-point “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” Likert scale. We reverse code where appropriate and normalize each response to a 0 to 1 scale, with ‘‘1’’ representing the most offensive anti-Latino position and “0” representing the least offensive position. We employ exploratory factor analysis on the seven items using the principal component factors method with orthogonal varimax rotation. We employ factor analysis because diagnostic tests on the scale revealed it not to be unidimensional scale (N = 3102, M = 0.41, SD = 0.17, weighted, α = 0.678, weighted).

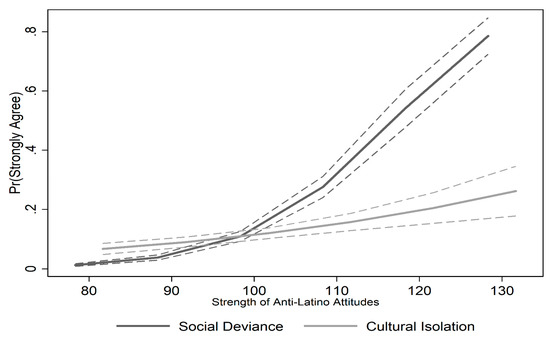

As Table 1 documents, diagnostic tests confirmed the factorability of these seven items: two factors explained 63.56% of the variance; factor loadings were above absolute 0.59 and generated a good Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy at 0.78 (indicating that correlations were compact). One factor, Social Deviance, was comprised from answers to the four items about gangs, welfare, education, and economic competition; another factor, Cultural Isolation, was comprised from answers to the three items about attachment to country of origin, adoption of American values, and belief that Latino distinctive culture enriches America. For ease of interpretation, we generate predicted factor scores using the regression method and rescale them to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10 for use in multivariate equations. Both factors constitute what we call anti-Latino sentiment. Blacks with high anti-Latino sentiment are considered to have strong negative prejudicial attitudes about Latinos; blacks with low anti-Latino sentiment are considered to have weak negative prejudicial attitudes about Latinos.

Table 1.

Results of the factor analysis on the responses to anti-Latino resentment measures using the principal component factors method with orthogonal varimax rotation.

Other independent variables of interest are registration status, black racial consciousness, immigrant heritage, prospective evaluation of the national economy, evaluation of local police, economic distress, and racialized black-Latino context. Registration status is measured by the question “Are you currently registered to vote here in the [indicated state of residency]?”. The Registered variable is coded “1” if respondents indicated that they were registered and is coded “0” otherwise. We operationalize black racial consciousness using the standard two-step black linked measure: “Do you think what happens generally to Black or African American people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life? {If yes,} Will it affect you:” (0 = No, 1 = Not Very Much, 2 = Some, 3 = A lot). Responses were normalized to a 0 to 1 scale, with “1” representing the greatest degree of consciousness (Black Linked Fate). We assess evaluation of law enforcement (Local Police) with “How good a job are the police doing in dealing with the problems that really concern people in your city? Would you say they are doing a …” (1 = Very good job, 2 = good job, 3 = Fair Job, 4 = Poor Job). We choose a measure about the quality of local law enforcement rather than a more specific measure about immigration enforcement to encapsulate overall attitudes about police and their interactions with residents. To that, while we acknowledge the complex relationship between local police departments and federal immigration and customs enforcement operations, especially when federal deportation officers are denied access to jails and prisons in “sanctuary cities” or do not receive the cooperation from local police departments that federal officials desire, we use Local Police to better approximate the broad array of content specific and temporal specific evaluations which we believe shape support for the dependent variables. Furthermore, we classify respondents by immigrant heritage according to their self-identified family ancestry: Heritage is coded “0” if respondents indicated that they could trace their family ancestry to “roots in America for generations going back to slavery” and is coded “1” if respondents indicated ancestry in “immigrant communities that are newer to America”. Seventy-one percent (71%) of respondents indicated having ancestral roots in America. We gauge prospective evaluation of the national economy with “In your opinion, are the economic conditions in the country getting better or worse?” (1 = Getting a lot better, 2 = Getting a little better, 3 = Staying about the same, 4 = Getting a little worse, 5 = Getting a lot worse). Higher numbers indicate a greater degree of anxiety about the economy and lower numbers indicate a greater degree of optimism (Economic Anxiety). We control for the impact of other sociodemographic and attitudinal variables using standard measures of age, gender (1 = female), education, household income, ideology (1 = very liberal, 5 = very conservative), and partisanship (1 = Strong Democrat, 7 = Strong Republican). We exclude missing responses and ‘do not know’ responses for all variables.

To assess the effects of contextual forces, we control for community-level disadvantage, ethno-racial circumstances, and geographic location. First, we control for disadvantage by utilizing the Distressed Communities Index created by the Economic Innovation Group, Inc. The DCI aggregates items measuring economic and social conditions which ostensibly shape mobility and neighborhood dynamics in America. Seven metrics comprise the index: (1) No High School Degree: Percent of the population 25 years and over without a high school degree; (2) Housing vacancy: Percent of habitable housing that is unoccupied, excluding properties that are for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use; (3) Adults not working: Share of the population 16 years and over that is not currently employed; (4) Poverty: Percent of population living under the poverty line; (5) Median income relative to state: Ratio of the geography’s median income to the state’s median income; (6) Change in employment: Percent change in the number of individuals employed between 2010 and 2013; and (7) Change in business establishments: Percent change in the number of business establishments between 2010 and 2013. DCI scores range from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate more economic distress. We append the DCI’s zip code-level distress scores (Distress Scores) to the individual-level dataset. Second, we control for ethno-racial circumstances by utilizing respondent answers to the following: “Please indicate the approximate racial/ethnic composition of the neighborhood where you currently live. Responses must add up to 100 percent.” Respondents indicated the percentage of “White, Black, Latino or Hispanic, Asian, and Other” persons they believed resided in their neighborhood. We use only what respondents reported for Latino or Hispanic (Perceived Percent Latino). Our subjective measure is strongly correlated with an objective measure of Latino presence derived from the 2015 American Community Survey 1-year zip code estimates of percent Hispanic, r (2554) = 0.53, p < 0.01. Given our theoretical interest in black perceptions, we use the subjective measure in our multivariate equations. Third, we geocode each respondent according to their location and assign said location to one of the nine appropriate census division (Census). We employ hierarchical ordinal logistic regression analysis using Stata 14 to model black attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policies as a function of demographic character, perceptions, and local contextual conditions [85,86]. (See Supplementary Materials for gologit2 models).

5. Findings

5.1. Black Overall Support for Anti-Immigration Policies and Postures

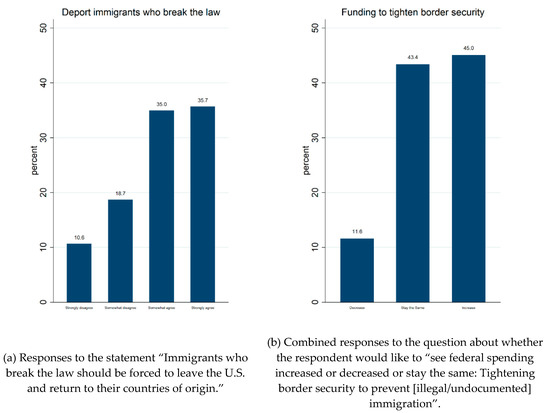

The distributions across the dependent variables underscore the heterogeneity of black public opinion about immigration policies in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 presidential election cycle. As shown in Figure 1, an overwhelming majority of respondents supported explicit anti-immigrant policies. Panel A illustrates that over seventy percent somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that law-breaking immigrants should be deported. Disagreement with the statement was the exception. Although the question did not tie deportation to specific crimes—for instance, the question did not differentiate between violent crimes, traffic crimes, and property crimes—the modal response is suggestive. Responses could have reflected support for a stringent universally-applied law enforcement regime or for a stringent group-specific law enforcement regime. The differences are substantively important: while support for stringent law enforcement represents a ‘law and order orientation’, targeted enforcement practices are more likely than not to have racially disparate impacts. The distribution in Panel B is important in this regard. Over eighty-eight percent favored the status quo or an increase in funding for border security measures aimed at preventing immigration. The experimental treatment had a non-significant impact on predicting preferences: Respondents receiving the “illegal” immigration cue (M = 2.35, SE = 0.02) were no more nor no less likely than respondents receiving the “undocumented” immigration cue (M = 2.32, SE = 0.02) to support increased funding, t (3101) = 0.49, p = 0.49.

Figure 1.

Black Support for Explicit Anti-Immigrant Policy.

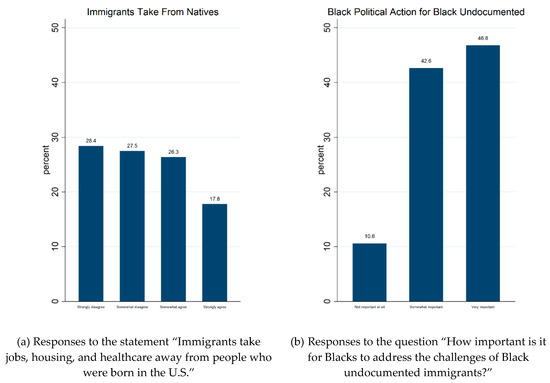

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of responses to the implicit policies measures, positions which show support or opposition to exclusionary postures which could lead to the enactment of discriminatory policies. Forty-four percent of blacks agreed with the statement that immigrants take jobs, housing, and health care from natives. Panel B shows more than supermajority supported (89 percent) the notion that it was important for black political activity to address the challenges of black undocumented immigrants. Overall, the distribution of black support for the explicit and implicit policies was unsurprising.

Figure 2.

Black Support for Implicit Anti-Immigrant Policy.

5.2. Modeling Black Support for Each Anti-Immigration Policy

Table 2 depicts results from hierarchical ordinal logistic regression models examining the impact of anti-Latino attitudes, socioeconomic and racial context, and demographics on black support for deporting immigrants who break the law. The ordinal dependent variable runs from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Overall, the multivariate models provide no evidence to support H1a, H5, and H6, but provide substantial evidence to support H2a, H3, and H4. We find weak support for H7. Model A (Perceptions) provides evidence that respondent beliefs that Latinos are socially deviant shaped their position on deportation, with strong beliefs associated with a greater likelihood of agreeing with deportation. Model B (Demographics) shows that, on average, older blacks, registered blacks, blacks claiming a non-immigrant heritage, and blacks with high levels of anti-Latino sentiment were more likely than their counterparts to support deportation. Economic anxiety was associated with a lower likelihood of agreeing with the statement. Females were also more likely than males to support deportation. The inclusion of contextual variables did not substantially alter the strength and direction of most predictors from Model B (see Model C Context). Black linked fate, neighborhood economic distress, attitudes about the local police, and perceptions about the proportion of Latinos in a respondents’ neighborhood were not significant predictors. Model C shows that conservatives were also more likely to support deportation than were liberals.

Table 2.

Odds ratios from the ordinal logistic models of support for deporting immigrants who break the law by anti-Latino perceptions, demographics, and registration status.

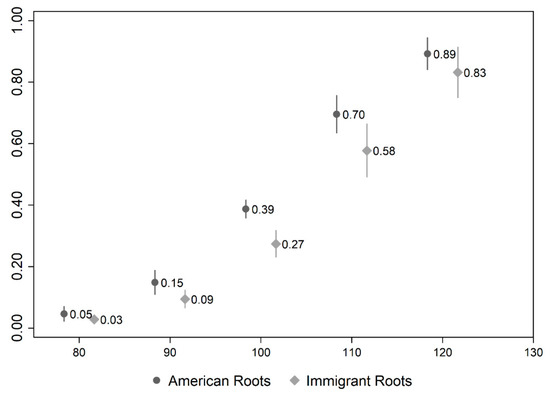

We graph the combined impact of beliefs about Latino social deviance and heritage in Figure 3, derived from estimates in Table 2 (Context Model) with other variables held at their means. Anti-Latino sentiment notwithstanding, blacks with American roots were predicted to have a higher probability of strongly agreeing with deportation than were blacks with immigrant roots. To demonstrate, a black person with American roots and a black person (AR) with immigrant roots (IR) are roughly equal in their strong support for deportation when their beliefs in Latino social deviance are below the mean. Moving to the mean of 100, however, AR strong support for deportation jumps from 15% to 39%, a 24-point increase. But the difference at the mean between AR blacks and IR blacks is eight points. One deviation above the mean (at 110) we see another large increase amongst AR blacks in favor of deportation, this time it is a 31-point increase. Thus, the differences between AR blacks and IR blacks are pronounced and significant, and this difference is driven by beliefs about Latino social deviance.

Figure 3.

Probabilities of strongly agreeing with the deportation of law-breaking immigrants.

Table 3 displays results from models estimating the impact of various attitudinal, contextual, and demographic forces on attitudes toward increasing funding for border security. Neither the experimental cue, heritage, nor registration status had discernible impacts on respondent attitudes toward the policy. Looking across Model A and Model B, we see that high levels of black linked fate were associated with a greater likelihood of supporting the status quo position regarding funding. In model A, for example, the result for black linked fate (OR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.54, 0.83], p < 0.000) shows that the odds of selecting the “increase funding” option decreased by 33 percent for each unit increase in black linked fate, holding all other variables constant. Moreover, respondents reporting no black linked fate (0) had a 0.50 probability of selecting “increase funding”, whereas respondents reporting the highest level of black linked fate (1) had a 0.40 probability of selecting “increase funding”. Results from Model B and Model C however offer dueling accounts about the import of black linked fate. Black linked fate was a significant predictor in Model B, but was a non-significant predictor in Model C.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from the ordinal logistic models of positions on border security funding by anti-Latino perceptions, demographics, linked fate, and experimental cue.

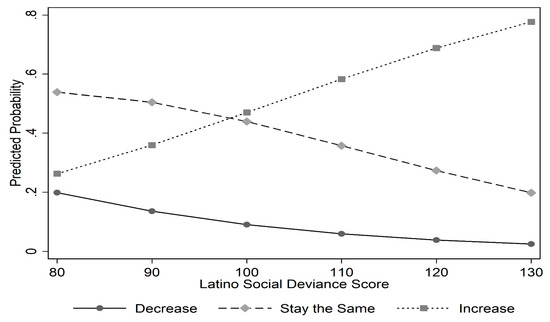

Nonetheless, ideological orientation and sentiment about Latino social deviance were significant predictors of support in the regression model. The odds of selecting “increase border security funding” increased by up to 4.6 percent for each unit increase in Social Deviance. Ideological conservatives were less likely to indicate a preference for a decrease in funding. Overall, findings in Table 3 support H1b (regarding black linked fate) and H2b (regarding social deviance), but contravene expectations laid out in H2b (regarding cultural isolation), H3, H4, H5, H6, and in H7. Figure 4 depicts the relationship between perceptions of Latino social deviance and this dependent variable using estimations from Model C with other variables held at their mean.

Figure 4.

Probabilities for the position on funding for border security at mean linked fate.

The estimates in Table 4 highlight the multiple attitudinal and demographic factors shaping black perceptions that immigrants take jobs, housing, and health care from native-born residents. Heritage, age, and registration status were significant predictors: blacks identifying with roots in American enslavement, older blacks, and registered blacks are more likely than their counterparts to support the anti-immigrant position. More specifically, our analysis of results from Model C indicated that unregistered blacks claiming American Roots were more likely to “somewhat disagree” with the statement (a probability of 0.36) than anything else, holding constant all other independent variables. Unregistered blacks with American Roots were more likely to strongly disagree with the statement (a probability of 0.28) than were their registered counterparts (a probability of 0.17). In contrast, unregistered respondents claiming Immigrant Roots had a 0.06 probability of selecting “strongly agree”, while their registered counterparts with Immigrant Roots had a 0.10 probability of selecting “strongly agree”. Consistent with H3 and H4, unregistered blacks with Immigrant Roots were most likely to strongly disagree with the statement (probability of 0.39) or somewhat disagree with the statement (probability of 0.36). Registered blacks with Immigrant Roots were likely to select the interior points of the response scale (a probability of 0.30 for “somewhat agree” and a probability of 0.35 for “somewhat disagree”). The largest difference in probability was amongst registered and unregistered blacks with Immigrant Roots who strongly disagreed with the statement: Registered blacks had a probability of 0.25 and unregistered blacks had a probability of 0.39 (a difference of 0.14).

Table 4.

Odds ratios from the ordinal logistic models of agreement that immigrants take jobs, housing and healthcare from natives.

Furthermore, higher levels of black linked fate and economic anxiety were associated with strong agreement with the statement that immigrants take from natives. For example, on average, blacks with the highest level of anxiety, those who believed that the economic condition in the country in 2016 was “getting a lot worse”, had a probability of 0.49 of somewhat agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement. By contrast, blacks with the lowest level of anxiety, those who believed that the economic condition was “getting a lot better” had a probability of 0.39 of somewhat agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement. Higher levels of education reduced the likelihood of agreement (Model B and Model C), as did household income (Model B). Respondent attitudes toward local police, the level of zip code economic distress, and respondent perceptions about the percentage of Latinos in an area were not significant predictors. Finally, across all three models, high levels of anti-Latino sentiment were positively associated with the anti-immigrant position.

We illustrate the impact of select attitudinal factors in Figure 5 and Figure 6. In Figure 5, we graphed estimates derived from setting all of the independent variables in Model C to their sample means except for each factor of anti-Latino sentiment. Three aspects of Figure 5 are noteworthy. First, the upward tilt of the line for Social Deviance (the darker of the two lines) is more dramatic than the upward tilt of the line for Cultural Isolation. Second, respondents located at more than one positive standard deviation from the mean of Social Deviance were predicted to have a higher probability of support than were respondents located at more than one positive standard deviation from the mean of Cultural Isolation. Third, respondents with the highest values on Social Deviance were estimated to have twice the predicted probability of respondents with the highest values on Cultural Isolation. On average, extreme beliefs about Latino social deviance were more consequential in shaping the position of blacks on this implicit anti-immigrant policy than were extreme beliefs about Latino cultural isolation.

Figure 5.

Probabilities for strongly agreeing that immigrants take by anti-Latino attitudes.

Figure 6.

Probabilities for position on immigrants take by linked fate.

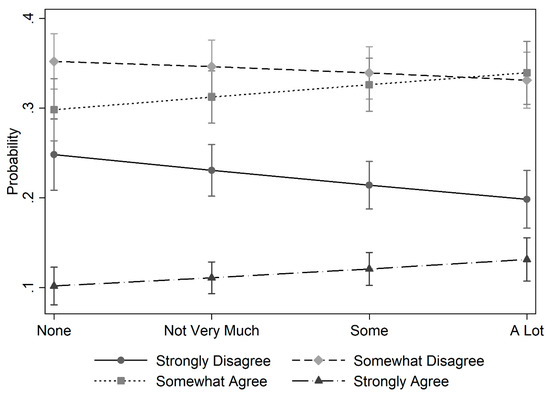

In Figure 6, we graphed predicted probabilities for the effect of black linked fate on agreement that immigrants take from natives, holding the other independent variables in Model C at their sample means. While all blacks were the least likely to strongly agree with the statement, respondents expressing no black linked fate were most likely to disagree with the statement. Moving from None (0) to A Lot (1) on the black linked fate measure however was only associated with small changes in the probability of choosing specific options: a −0.05 change in choosing “strongly disagree”, a −0.02 change in choosing “somewhat disagree”, a +0.04 change in choosing “somewhat agree”, and a +0.03 change in choosing “strongly agree.” Nonetheless, these small changes highlight the consequence of high racial group consciousness in the presence of mean level anti-Latino sentiment. Weak (or weakened) propensity for blacks to express disagreement with the statement could reflect, at best, a susceptibility amongst blacks to support anti-immigrant policies in the future, and, at worst, reflect black reluctance to actively oppose anti-immigrant policies.

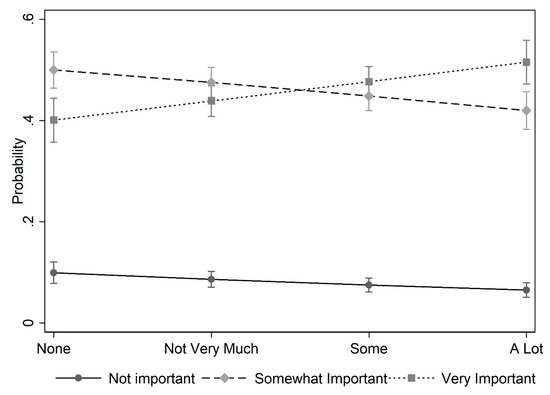

The results in Table 5 underscore the effect of black linked fate and anti-Latino sentiment on support for black advocacy on behalf of black undocumented immigrants. Contrary to expectations, we found no significant effects for economic anxiety, heritage identity, zip code economic distress, and perceptions about the percentage of Latinos in a neighborhood. Being registered however reduced the likelihood of supporting inclusive black advocacy. The estimates for Model C in Table 5 thus reveal that respondents were cross-pressured by black linked fate and anti-Latino sentiment. Consistent with our expectations about anti-Latino sentiment (H2d), higher levels of the animus, whether Social Deviance or Cultural Isolation, were associated with a reduced likelihood of supporting inclusive advocacy. Moreover, consistent with our expectations about black linked fate (H1d), higher levels of the measure were associated with an increased likelihood of selecting the “very important” response option. Figure 7 depicts the marginal effects at the mean for black linked fate derived by setting all other independent variables in Model C to their sample means. Respondents reporting no linked fate (0) had a predicted probability of 0.40 of selecting “very important”, while respondents reporting a lot of linked fate (1) had a 0.52 predicted probability of selecting “very important”.

Table 5.

Odds ratios from the ordinal logistic models on the importance of blacks to address challenges of black undocumented immigrants.

Figure 7.

Probabilities for the position on supporting black undocumented immigrants by linked fate.

To further explore the impact of anti-Latino sentiment and of black linked fate on support for black inclusive advocacy, we derived the average marginal effect of the aforementioned variables as a counterpart to the marginal effects at the mean depicted in Figure 7. The average marginal effect for each factor of anti-Latino sentiment was small (nearly zero) but significant (p < 0.01), which was expected given how we rescaled the factor scores to have M = 100 and SD = 10. By contrast, the effect for black linked fate was larger (−0.036, −0.074, and 0.110, all p < 0.001), meaning that, on average, higher levels decreased the selection of “not important at all” and “somewhat important” but increased the selection of “very important”. That linked fate was a significant predictor, while heritage identity was a non-significant predictor, in the multivariate models bespeaks to the continued potency of racial group consciousness in black politics. It is highly likely that some blacks did not see substantive differences between the challenges faced by black undocumented immigrants and the challenges faced by other persons sharing a black ascriptive characteristic.

6. Conclusions

Our results support the general conclusion that black linked fate and negative attitudes about Latinos affected blacks’ support for restrictive immigration policies and anti-immigrant postures closely associated with the 2016 Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump. Specifically, our multivariate analysis of the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey revealed the following about black response to policies and postures which did not explicitly reference Latinos or Hispanics. First, black attitudes about Latino Americans clustered into two factors, beliefs about the propensity for Latinos in America to culturally isolate themselves and beliefs about the propensity for Latinos to engage in anti-social deviant behavior. Blacks with strong negative prejudicial attitudes were more likely to choose the restrictive and exclusionary response options than were blacks with weaker negative attitudes. Second, the presence of black linked fate did not consistently reduce black support for the anti-immigrant position. Third, in bivariate equations, black linked fate was shown to be strongly correlated with only one factor of anti-Latino sentiment: cultural isolation. Fourth, after controlling for attitudinal, demographic, and contextual influences, economic anxiety was found to only affect responses to the statement which explicitly mentioned immigrants taking resources from natives. Fifth, blacks identifying as principally having roots in American heritage via racial enslavement were more likely to choose the anti-immigrant option than were blacks identifying as principally having roots in immigrant heritage.

Together, these results suggest that blacks’ sense of linked fate and national identity in 2016 worked alongside concerns about their racial group’s socioeconomic position and prejudicial attitudes about Latinos to shape their support for policies and postures hostile to all immigrants. Because our anti-Latino sentiment measure reflects the racial, cultural, and economic anxieties of respondents, our findings show that blacks, like other Americans, often conflated Latino and (detested) immigrant. In other words, we assert that black support for some anti-immigrant policies and postures confirms the resonance of Trump’s policy prescriptions beyond whites. This is not to say that a large number of blacks voted for Trump in 2016—indeed, survey and exit poll data wholly suggest otherwise. Nonetheless, we were surprised that blacks with high racial group consciousness did not resoundingly reject the coupling of deportation and criminal activity. Given the heightened publicity surrounding the Movement for Black Lives (also known as Black Lives Matter) and surrounding community campaigns against police brutality in Ferguson (2014) and in Baltimore (2015), we found it surprising that blacks in 2016 supported immigration policies which could exploit the criminalization of blackness, enhance the misuse of police power, or both. Similarly, we were surprised that local context and education did not have a more substantial impact on black respondents. Neither our measures of Latino presence in a neighborhood, our measure of the economic distress of a zip code, nor our measure of educational attainment were significant predictors for all of the four dependent variables. Education was a significant predictor only for the question about whether immigrants take from natives. These null findings challenge assertions that low educational attainment, economic deprivation, and heavy contact with Latinos drives black hostility to immigrants above and beyond whatever strong prejudicial attitudes may exist.

Although these findings may seem surprising, they have to be tempered with an acknowledgement of black national identity. While black ideas of Americanness are different from other racial groups, blacks are still Americans—as such, to the extent that blacks may also be protectionist of their own individual and racial group’s interests, this fact should not be read as a betrayal of their groups’ politics. What is more, it may be that the negative rhetoric of the 2016 Trump campaign and its anti-black elements may have amplified black reluctance to advocate on behalf of those groups that blacks felt were their competitors (for jobs, for services, for government attention, or what have you). Likewise, our findings should be tempered with an acknowledgement that blacks may not have a well-developed set of opinions about the issue of immigration. The issue of immigration has not traditionally been included as part of the black issues repertoire. Indeed, these findings reported here and findings reported by the African American Research Collaborative’ 2016 survey show a continuity in black ranking of other issues as more important. To that, even black elites have not sent clear signals about the issue of immigration and have not adequately contextualized the issue for their constituents. This is not to say that the actions or inactions of black elites determine the state of black opinion on immigration, but political elites play important roles in framing issues and in messaging about issues for the mass public. That there has not been a consistent, identifiable immigration agenda for black people in the early twenty-first century may explain what seem like inconsistencies in black opinions. It is important to note, however, that mass opinions are often incoherent and peoples’ opinions are often most consistent on issues that are salient to them. That the issue of immigration may not have been salient to black people in 2016 could explain their attitudes across the expanse of immigration related issues we test in the paper.