Abstract

1. Background: While many studies analyze the functions that images can fulfill during humanitarian crises or catastrophes, an understanding of how meaning is constructed in text–image relationships is lacking. This article explores how discourses are produced using different types of text–image interactions. It presents a case study focusing on a humanitarian crisis, more specifically the sexual transmission of Ebola. 2. Methods: Data were processed both quantitatively and qualitatively through a keyword-based selection. Tweets containing an image were retrieved from a database of 210,600 tweets containing the words “Ebola” and “semen”, in English and in French, over the course of 12 months. When this first selection was crossed with the imperative of focusing on a specific thematic (the sexual transmission of Ebola) and avoiding off-topic text–image relationships, it led to reducing the corpus to 182 tweets. 3. Results: The article proposes a four-category classification of text–image relationships. Theoretically, it provides original insights into how discourses are built in social media; it also highlights the semiotic significance of images in expressing an opinion or an emotion. 4. Conclusion: The results suggest that the process of signification needs to be rethought: Content enhancement and dialogism through images have a bearing on Twitter’s use as a public sphere, such as credibilization of discourses or politicization of events. This opens the way to a new, more comprehensive approach to the rhetorics of users on Twitter.

1. Introduction

Images are a powerful vector of signification that social media users resort to more and more. Although it seems evident that understanding text–image relationships is of great importance to grasping the full meaning of any message, it is unfortunately too common to read studies about Twitter in which tweets are treated exclusively as text data or, more rarely, as platforms for sharing visuals. Many of these studies focus on social functions involving images such as the rise of ‘citizen journalists’ [1], the documentation and management of live catastrophes [2] and political crisis [3], or they limit themselves to analyzing how images contribute to the discursive construction of an event [4,5].

The vast majority of studies on Twitter focus on text messages. The issues studied are rich and varied, exploring, for example, the syntax and writing styles produced under Twitter’s 140-character constraint or focusing on Twitter as an election propaganda resource, examining the self-presentation of candidates, the ideological content, or the flashes of wit that this format allows politicians to exhibit in writing. Others deal with texts as unveilings of personal privacy. The fact that little is said about the accompanying images is largely due to real technical difficulties. The standard software for the extraction of tweets often takes little account of images and videos, which do not generate automatic classification. For a corpus of thousands of tweets (to say nothing of a corpus of millions), computer processing of texts is already complicated, and adding images in their various formats and functions can quickly become difficult and time-consuming. Yet images are becoming increasingly important in social media, as can be seen in the success of networks featuring images such as Instagram, Pinterest or Snapchat, and of video networks like Facebook Live or Periscope. The strategies developed by users to make their discourses more visible are often based on images, which makes, in the words of Barthes [6], the ‘relay’ relationship (when texts add information to images) more frequent than the ‘anchorage’ relationships (when texts fix the meaning), therefore encouraging researchers to explore its variations on social media. Many articles base their visual corpus on extractions of images coming from social networks. They expose methodological difficulties [7,8] or search traces of a new visual culture, especially through selfies [9,10], the art of exposing subjectivity [11] or self-esteem enhancement [12].

The relationship between text and image is admittedly a very specific topic of research but is essential to understand meanings on social media. Detaching texts from images or postulating the superiority of texts over images runs the risk of skewing research results. This paper provides theoretical and methodological tools and suggestions for working in this as-yet largely unexplored field and emphasizes the necessity of rigorous qualitative selection and analysis of tweets, proceeding first by subsamplings and successive filtering, and then by semiodiscursive analysis. This paper offers renewed methodological insights into manual selection and coding of tweets. With this objective, we chose to illustrate our approach through a case study focusing on health during a humanitarian crisis, the 2014 Ebola epidemic regarding its least-understood path of transmission: Sexual transmission from survivors. We compared our results with an earlier analysis of Twitter texts in order to understand if and how images corroborate or inflect texts.

The 2014 Ebola outbreak and the sexual transmission makes it a fitting case study to understand tweets in a new way, as it raises worrying questions concerning potential new outbreaks, the emergence of a ‘new AIDS’, and the contamination of territories that were previously spared. Ebola represents the first pandemic in the era of widespread use of social media. The sensitivity of this epidemic has resulted in extreme speech and crystallizes specific problems, such as: The expression and sometimes confrontation or confusion of different registers of discourse (information, disinformation, prevention, and rumor); the undermining of public health policies; or questions about which prevention discourses are rhetorically conducive to text–image combinations (posters, graphics, etc.).

Analysis of Twitter images is encouraged by the rich visual potential of Ebola, including imagery about Africa at the time that the virus appeared as a global threat [13]; its visually dreadful symptoms; or the sexual particularity of the transmission. As Sander L. Gilman [14] underlined, ‘icons of disease appear to have an existence independent of the reality of any given disease.’ If ‘the creation of the image of [the disease] must be understood as part of this ongoing attempt to isolate and control disease’, the sharing of Ebola images on Twitter should be a fruitful field for studying how people receive and rank official information and rumors, for understanding prevention addresses and warning signs, and for investigating discourses of reassurance and fear during a global humanitarian crisis.

We propose a four-category classification of the relationships between texts and images—illustration, commentary, repetition, and complementarity. Discourses appear particularly amplified when users instrumentalize text or image to go beyond the mere dissemination of information and to express emotion, political positions, doubts or personal stances. Our results show how the analysis of text–image combinations reveals meanings that would not have been discerned otherwise, offering opportunities for renewed theoretical and empirical perspectives on text–image combinations. The supposedly restrictive 140-character limit of Twitter reveals in practice an inventive plasticity: Texts and images are not constrained to the designated spaces, and discourses take advantage of this. Furthermore, our conjoint analysis shows that in cases where texts are quite standardized, images can be used to inflect the event’s framing; equally, a single image can be shared with contradictory discourses, thus conveying social debates. Often, even official poster preventions end up being moot points rather than being accepted as information.

1.1. Text–Image Relationships in Tweets

While many studies take into account the functions that images can fulfil during humanitarian crises or catastrophes, an understanding of how meaning is constructed in text–image relationships is lacking. Despite the part played by imagination and real images about Ebola, and despite the fact that social media have been scientifically studied to understand social discourses about Ebola, there has been no research to date on the construction of discursive strategies in a holistic way. In a time of uncertainty such as that triggered by an Ebola epidemic, how do people use social media to disseminate information, to participate in debates or controversies, to be heard and to express emotions?

Text–image combinations have been the subject of numerous articles that focus on the functions carried out by images. Twitter can incite a ‘seamless convergence of photographic and textual information from everyday ‘citizen journalists’ that can extremely rapidly disseminate a picture [1]. Images of catastrophes such as the storm that hit Belgium’s Pukkelpop music festival in August 2011 offer rapid and undeniable proof of the damages [2]. When analyzing the 2011 UK riots, Vis et al. [3] emphasized the ‘complex relationships between actual and virtual space involved with the production and distribution of Twitter images’: By uploading pictures of a crisis, users participate in an eye-witnessing process. The researchers further described the sharing of television screenshots as a new relationship between audiences and the media content that people turn into a ‘still, shareable image’. While conducting a study of images of Ebola on Instagram and Flickr, Seltzer et al. [5] identified four themes of images (health care workers; West Africa; Ebola virus; and artistic representations of Ebola) and four themes mixing images and embedded text (facts, fears, politics, and jokes), while 22% of the collected images were irrelevant. Their results showed that social media were used for information dissemination or information exchange and that there were differences between platforms: Instagram images were mostly jokes or simply irrelevant, while Flickr images primarily represented health care professionals at work. Seltzer et al. therefore mentioned the need for a better use of the particular type of communication offered by social media for health messaging and education. Among the images in their sample that contained embedded text, 23% were jokes that they categorized into five main themes: Political jokes, mocking of fearful people, racial stereotypes, costumes (e.g., for Halloween), and the implication that someone or something has Ebola. They noted no necessary equivalence between the content of the joke and the reality of transmission modes. They therefore supported what might be called an ‘upward’ communication strategy, adopting the visual codes of Twitter users to counter misinformation. They emphasized that ‘social media kinetics remind us of classic lessons in communication, which emphasize not just content, but also source, medium, and tone.’ This call for engaging with users on their own terms is echoed by Kapp, Hensel, and Schnoring [15] who, drawing on uses and gratifications theories, asked how people screen information according to their motivations (‘diversion, personal relationships, personal identity and surveillance’). Other studies underlined the need to understand emotions at work in tweets containing images. When studying Twitter images of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, Kharroub and Bas [4] showed how images contained more ‘efficacy-eliciting’ content than ‘emotionally arousing images,’ whereas other studies such as the one led by Papacharissi and de Fatima Oliveira [16] found that Twitter texts contained signs of emotions and personal opinions. The preceding studies have largely categorized images according to their discursive register or rhetorical role in a sensitive situation (storm, insurrection, health crisis, etc.). Our study proposes to analyze various strategies of articulation between text and image that emerged during a specific humanitarian crisis.

1.2. Ebola and Social Media

The relationship between Ebola and social media has been the subject of numerous scientific papers, which agree on social media’s potential for information dissemination [17,18,19,20]. Rodriguez-Morales, Castaneda-Hernandez, and McGregor [21] note a 21-fold ‘spike’ in tweets in the 24 h following the announcement of the first Ebola diagnosis on US soil on 30 September 2014 (see also [22]). This data suggests that users echo news activity, which is encouraged by Twitter’s nonhierarchical nature [23], and that they do so with relative autonomy. Odlum and Yoon showed some pronounced spikes when official announcements concerned actual American cases of Ebola (‘American doctor found Ebola positive’ and ‘American fighting Ebola coming home to the US’), revealing a clear concern about outbreaks that are close geographically or culturally. However, outbreaks do not need to be geographically close to trigger substantial and immediate responses online: More tweets were posted from the USA than from the countries actually affected by the epidemic [24].

These studies identify a number of activities in which the use of Twitter offers major advantages: Information dissemination; prevention; outbreak mapping; facilitating communication between scientists, policymakers, and citizens [5,19]; active participation from users; recognition of popular discourses, including both their substantive content and their degree of concern. Regarding the latter, Odlum and Yoon showed that popular communication includes both public concern and echoing of news alerts. The question of media effects re-emerges here as media uses are suspected to cause disproportionate fears, although this perspective tends to ignore reassuring coverage, as Ungar [25] showed regarding the Ebola outbreak in Zaire. Seltzer et al. clearly described the paradox regarding Ebola in the US: While as of December 2014 there had been only two deaths from Ebola in the US (during the same time, West Africa counted over 5000 deaths), Americans ranked Ebola third in their list of biggest health problems (just after costs and access to health care). As much as the importance of information dissemination in social media is irrefutable, the insistence on the sole texts of the tweets appears as a bias that makes other uses less visible. As we will argue, analyzing texts and images together offers the opportunity to refine the analysis of the different kinds of information and the different ways of spreading them.

2. Materials and Methods

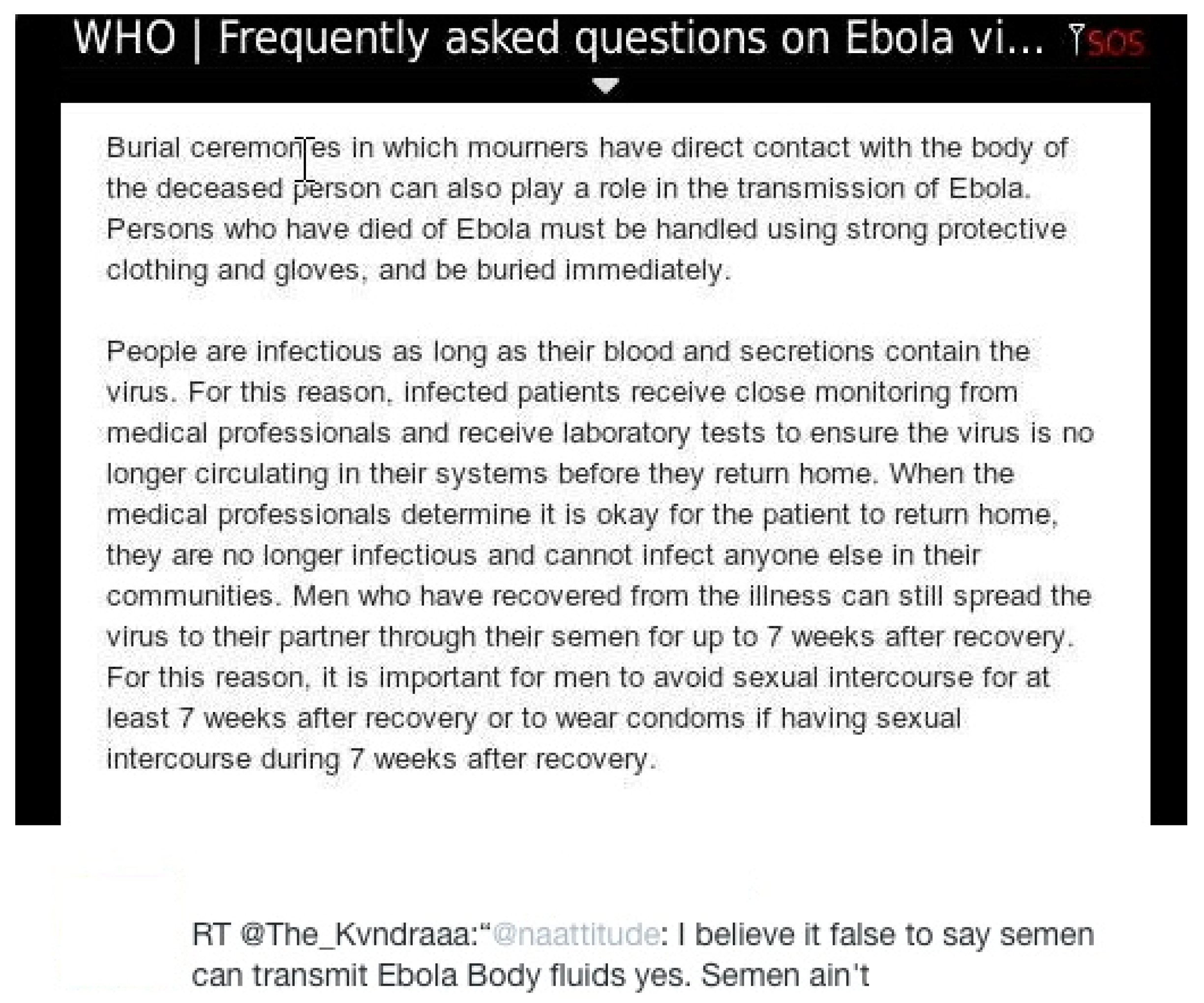

Data were processed both quantitatively and qualitatively through a keyword-based selection, which, as studies have shown [17,20,22], is the most efficient methodology to narrow down a massive corpus. Using “Ebola” and “semen” as keywords, in English and in French, we retrieved a total of 210,600 tweets (including retweets) over the course of 12 months (1 April 2014 to 1 April 2015). During this first selection, data anonymization was carried out in accordance with ethical standards. While information was available regarding the time distribution, exploration of these data was largely irrelevant to our study. The construction of the corpus consisted of a succession of qualitative analysis: We took two core samples of 6000 tweets that were manually coded to select two lists of keywords, one that would indicate the presence of an image and one that would indicate the discussion around the sexual transmission of Ebola. We retrieved 14,316 tweets containing an image. It should be noted that we encountered several tweets articulating similar texts and similar images (particularly in the case of tweets disseminating information). Because there was no scientific value in keeping such duplicates, we chose to remove them, producing a corpus of 12,900 tweets. Still, a large number of these tweets did not have any link to the sexual transmission of Ebola, leading us to construct another core sample to identify a relevant keywords list. The crossing of this two-keywords-based selection led to a corpus of 560 tweets, from which manual coding deleted all tweets nonrelated to the sexual transmission of Ebola. The final corpus consisted of 182 tweets (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow.

3. Results

3.1. The Need for Qualitative Methods: Subsampling, Successive Sievings, and Semiodiscursive Analysis

Users combine several levels of discourse when they produce articulations of text and image online, making it impossible to decipher the various meanings by simply analyzing text and/or images separately. Rather, articulating the two produces a cascade of meaning effects that can be best seized by a semiodiscursive analysis, drawing attention to what is given access to representation and what is not; and with which framings. A qualitative analysis of text–image relationships therefore benefits from successive re-examinations of different samples of tweets extracted from the sources, making it possible to identify original discursive forms that a quantitative analysis would otherwise have concealed. Therefore, while a keyword-based selection has been proven reliable, subsampling, successive filterings, and semiodiscursive analysis have proven to be useful tools to identify, select, and interpret complex productions of meaning, notably in text–image articulations. This is all the truer in that a qualitative analysis of tweets rapidly shows how users opportunistically reference “trendy” subjects when discussing topics that actually have little to do with them. Our research was rapidly confronted with individuals evoking Ebola and semen for other reasons than actually discussing the topic at hand (i.e., the sexual transmission of Ebola), or posting images of Ebola that had little to nothing to do with the disease or the health crisis. This led us to further tap into primary sources in order to select tweets that were truly related to text–image relationships during a health crisis. We emphasize that a purely quantitative selection of a corpus in these sources would not have identified these tweets. For this reason, our qualitative analysis of tweets relied first and foremost on constant subsampling, identifying both the generic terms indicating the presence of an image and the words most used to discuss the sexual transmission of Ebola. Our investigation, based on selecting 6000 tweets out of the corpus, reading them, and manually coding them, confirms that the analysis of complex meanings presented as a combination of text and image cannot skip a human interpretative stage, which itself requires constant recalibrations.

The first step was to select all tweets containing an image. This was made easier by our software (developed by the firm Semiocast), which automatically translated and copied the URL of the image into the tweet. This allowed us to search for generic terms indicating the presence of an image in a tweet. Taking into account the time that could be devoted to qualitative analysis with such a huge corpus, an initial sampling target of 6000 tweets was selected that could be widened if the results did not answer our initial interrogation or if they led to new hypotheses. The operative keywords were obtained after a first sampling pass, using these 6000 tweets containing “http” and opening every link: The final list contained the words “photo”, “instagram”, and “ifunny.” In this first pass, a total of 14,316 tweets containing an image were identified in the 210,600 tweets containing the words “Ebola” and “semen”. Because users easily resort to Twitter’s image feature, and because this feature was automatically translated in our database, the word “photo” was pervasive (916 tweets containing “photo” out of the 6000 compared to only 11 and 9 tweets for “Instagram” and “ifunny”). Simultaneously, the first selection of 210,600 tweets containing “Ebola” and “semen” was not precise enough to narrow down tweets discussing the sexual transmission of Ebola. A first core sample of 6000 tweets allowed to identify the fourteen keywords that were selected: “abstinence”, “swallow-“, “intercourse”, “condom”, “unprotected sex”, “hav-sex”, “fellatio”, “masturbate”, “secretion”, “semen”, “sex”, “sperm”, “vagina”, “sleep”, and “STD”, and their French equivalents. This qualitative selection resulted from an analysis of the discourses at work: Inside jokes, particular vocabulary of the event, popular expression, online vernacular, acronyms, etc. The application of this two-keywords-based selection led to a corpus of 560 tweets.

The preliminary qualitative analysis of these 560 tweets led us to return to the corpus to refine it, because our first results showed that the collected images had still surprisingly little to do with Ebola. The word “Ebola” was mostly used for other objects or contexts, with stylistic devices, some humoristic (“This soap is $195, it better wash Ebola, wash HIV, wash Malaria, shit.... It better wash all my sins away”, “Oh my god stop tryin to kiss me you have ebola”) or metaphorical (“milk give you aids Ebola tetanus and crabs too”; a high school picture accompanied by the hashtags “#School #Friends #Ebola #Aids”). The vast majority of tweets referenced the virus only as a way to attract attention or to take part in a discussion, making most of the corpus off-topic and requiring the elaboration of a new and more precise corpus. The pervasive use of hashtags caused a real diversion of meaning. Rather than contributing to a conversation around a theme, some Twitter users—out of pure opportunism and the desire to be more visible—inserted themselves into the conversational thread of a hashtag even when not addressing the hashtag theme. (As a side note, researchers should use great caution when considering the metrics of tweets behind the most popular hashtags. When a hashtag is used, the probability is high that parasitic and opportunistic tweets distort metrics by wrongly amplifying them). Therefore, to avoid off-topic text–image relationships, we coded qualitatively the 560 tweets and removed all the ones that were strategically using Ebola as a joke or a metaphor and we kept only the ones addressing the sexual transmission of Ebola. This produced a final corpus of 182 tweets.

3.2. Four Text–Image Relationships During Ebola Epidemics

Our data indicated four kinds of text–image relationships: Illustration; commentary; repetition; and complementarity. As Martinec and Salway [26] have shown, new media are prone to displaying text–image relationships with equal status (when one does not modify the other or when each one modifies the other). Our four-category classification shows how users employ or sometimes twist the technical devices so that posted images and texts produce the intended meaning in their reciprocal modification.

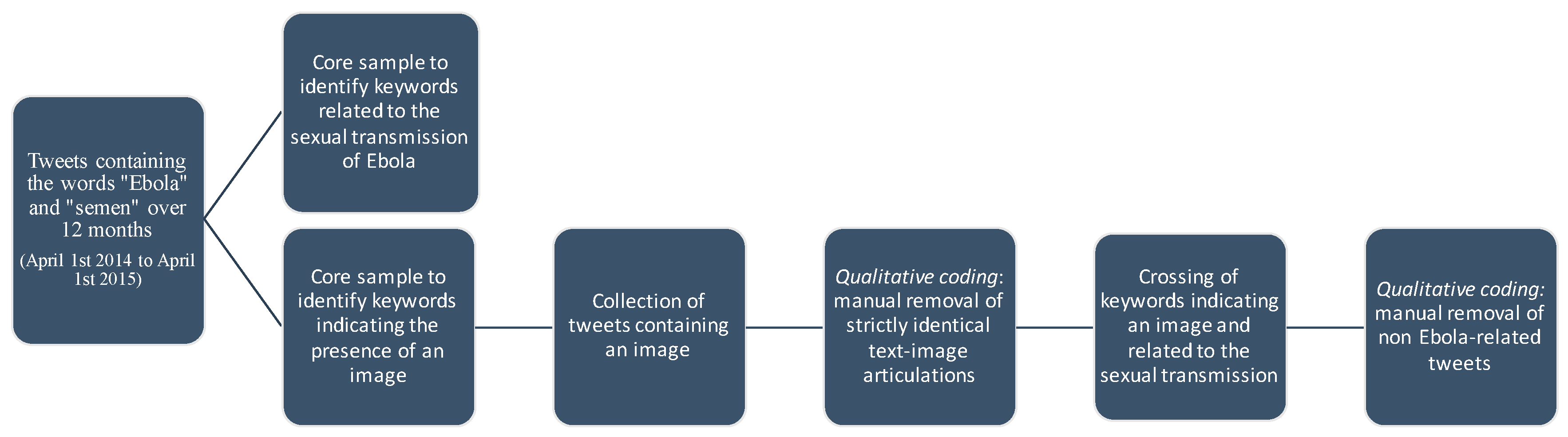

- Illustration (Figure 2). A majority of the images (56%) are an illustration of the text or rather of the thematic focus addressed in the tweet. Illustrations are interesting as they demonstrate how variably the event can be framed. Many offer a spectacular image of the disease by showing doctors wearing ultraprotective suits. The disease is more frequently portrayed using those who help the patients than the patients themselves. Another visual is the molecular representation of the virus, which is more or less stylized. Thanks to its specific form and frequency of appearance, this image can trigger an immediate identification of the subject matter, like doctors in full protection suits, but without the anxiety impression.

Figure 2. Illustration.

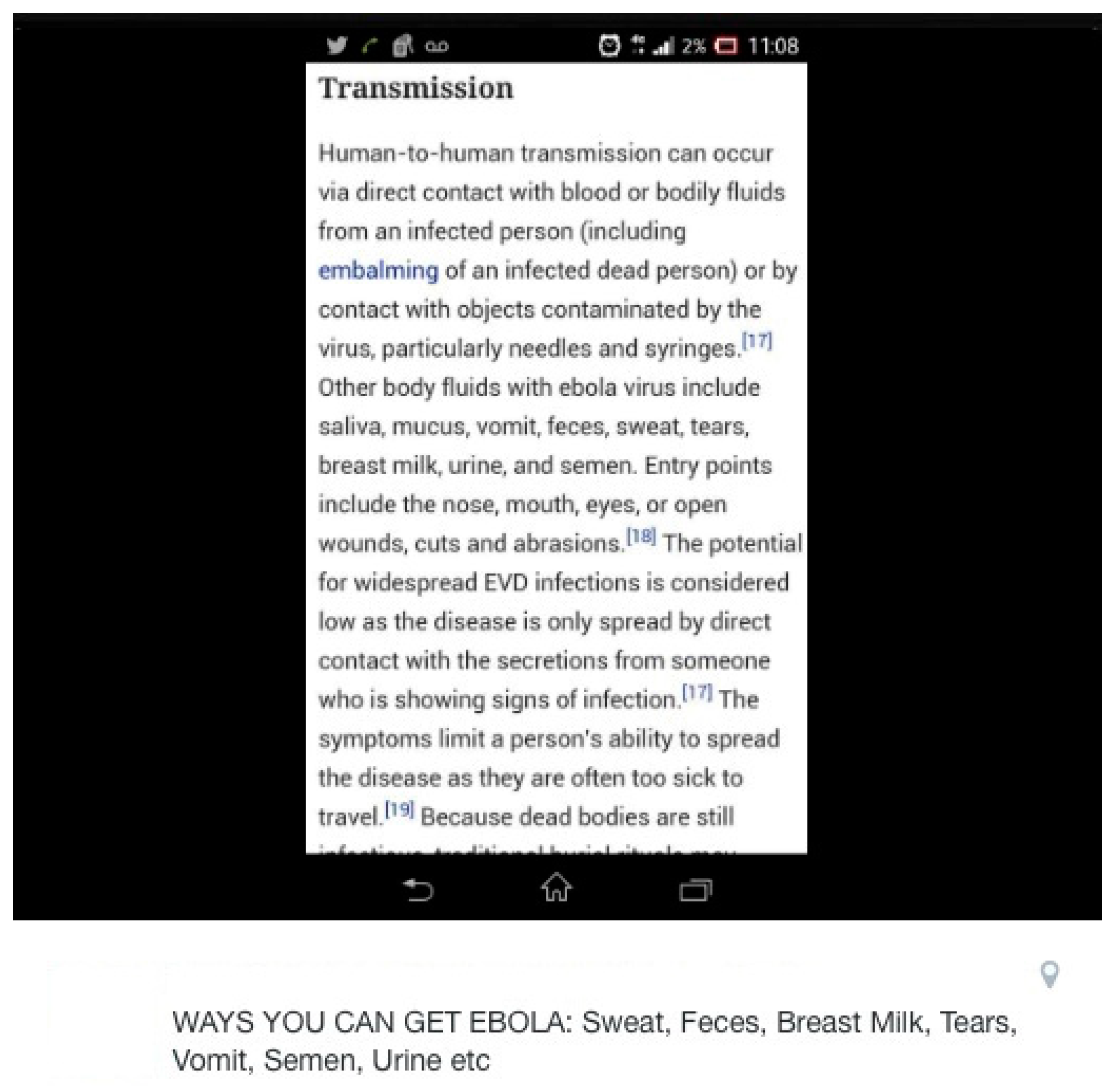

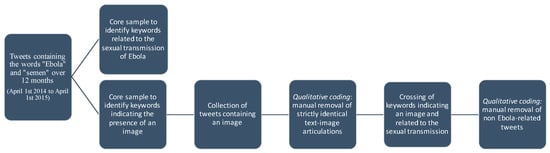

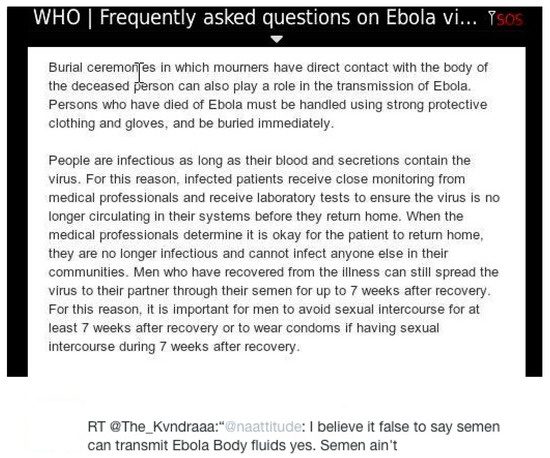

Figure 2. Illustration. - Commentary (Figure 3). Text–image combinations can also be used to provide commentary (21%), for example when texts contradict or doubt the information contained in the image (“RT @Th…:@na…: I believe it false to say semen can transmit Ebola Body fluids yes. Semen ain’t” accompanied by a screenshot of the WHO’s FAQ webpage mentioning the sexual transmission of Ebola).

Figure 3. Commentary.

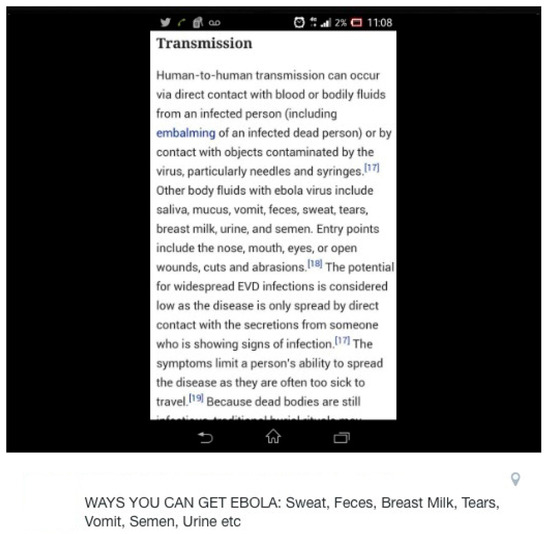

Figure 3. Commentary. - Repetition (Figure 4) was also noted (16%) between text and image: In order to highlight the information, users tweet the same text as the one contained in the image. The 140-character constraint sometimes pushes users to sum up the information contained in the image: For example, when displaying a screenshot of the transmission section of the virus’s Wikipedia page, one tweet summarizes “WAYS YOU CAN GET EBOLA: Sweat, Feces, Breast Milk, Tears, Vomit, Semen, Urine etc.”. The image area thus becomes word-based, while the text area contains hooks whose purpose can be to both summarize the content and to encourage the reading of the whole text.

Figure 4. Repetition.

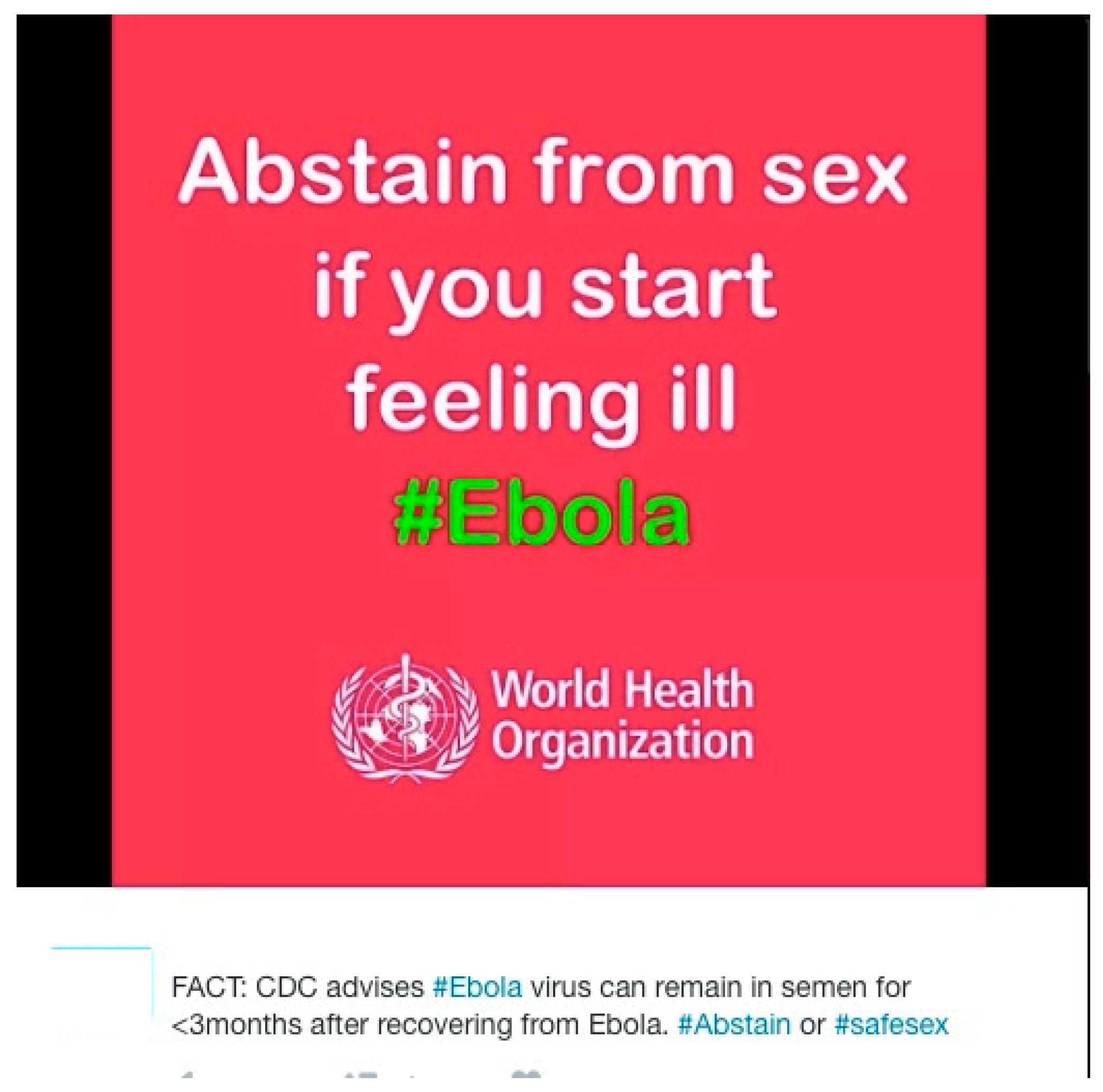

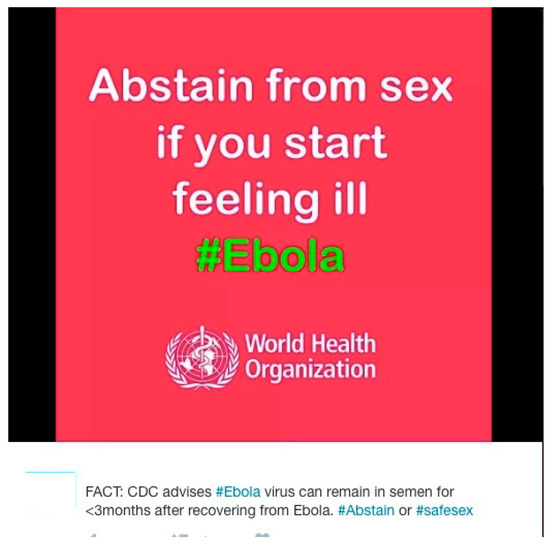

Figure 4. Repetition. - Complementarity (Figure 5). Finally, we noted complementarity between text and image, as when a tweet comments on a WHO prevention poster advising to “Abstain from sex if you start feeling ill. #Ebola” by adding “FACT: CDC advises #Ebola virus can remain in semen for >3months after recovering from Ebola. #Abstain or #safesex.” Images are often a second discourse, a way of saying something more than what is in the text.

Figure 5. Complementarity.

Figure 5. Complementarity.

Half of the tweets in our sample disseminated information without any added comment and contained an illustration as a visual. In one set comprising 102 tweets, news articles were shared using a common structure: The text contained the title of the publication while the image was the same illustration as is displayed on the website page to which the tweet links. One can assume this is due to the fact that newspaper websites make it possible to tweet their article with a predetermined format, making it very likely that those tweets originated from the reading of the article. These data suggest Twitter is a preferred sphere for information dissemination.

Although tweets featuring news articles are the most likely to contain illustrative images, these images are generally so varied that similar headlines are often accompanied with very different illustrations, framing the event differently. They include pictures related to love, affection, and sexuality, ranging from representations of spermatozoa or condoms to images showing affection between individuals (Figure 6) or calling for solidarity (e.g., a drawing of hands forming a heart).

Figure 6.

Shared image showing affection between individuals.

Ebola appears as a risk from within social links which people must protect themselves from and as a threat to social links that must be preserved. Images also represent the virus itself, mostly in microscopic view, thus offering a scientific perspective on the outbreak. Other newspaper articles illustrate the Ebola outbreak with quotidian images of people in the streets. Lastly, a set of interestingly similar images represents people fighting Ebola: Doctors examining a body, military personnel explaining a planned action, caregivers helping a sick man, etc. One striking feature of this set is that the depicted people are outdoors, on the move, and often wearing Hazmat suits (Figure 7): They are shown taking care of a sick person or dealing with a dead body, putting a mask on, organizing a protected area. Possible interpretations of the high frequency of Hazmat suits are that they evoke the violence of the virus or that they represent health crisis management.

Figure 7.

High frequency of Hazmat suits.

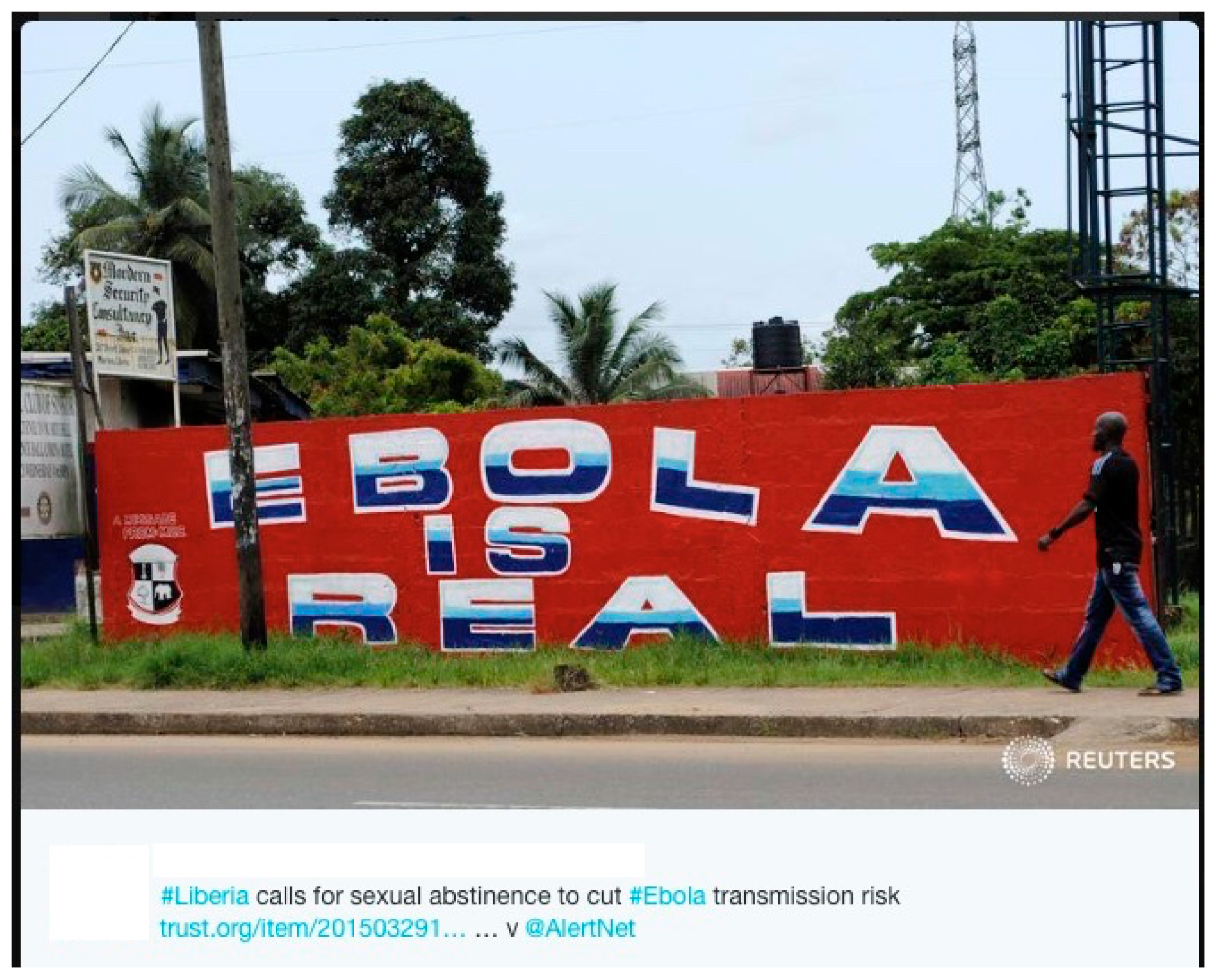

Moreover, as Joffe and Haarfooff [27] pointed out, the high frequency of westerners wearing Hazmat suits gives the impression of a disease that was “controllable by western science, [as] part of a world of make-believe, of science fiction”. Another example of how images frame the event differently is that while all headlines containing the word “condom” are very similar, the accompanying illustrations vary. Although the texts are repetitious—“#Ebola survivors told to use condoms - virus can live in semen for 70+ days”, “Ebola survivors told to use condoms to prevent virus spreading”, “Male #Ebola survivors told to use condoms”, “Ebola survivors told2 use condoms #West #SouthAfrica”—the images are as varied as condoms, a man washing his hands, a man walking outdoors in front of a prevention sign bearing the slogan “Ebola is real” (Figure 8), or a microscopic view of the Ebola virus.

Figure 8.

Man walking outdoors in front of a prevention sign bearing the slogan “Ebola is real”.

Images successively represent Ebola as: An intimate and individual problem requiring safe-sex measures; an interpersonal risk necessitating sanitary precautions; a health crisis that takes place in the public sphere and which requires prevention campaigns; or a virus seen from a scientific perspective.

A second set of 80 tweets shows more hybrid combinations of information dissemination and personal comments. Here, text–image relationships are not homogeneously aimed at illustration (only 13%) but vary between commentary (42%), repetition (28%), and complementarity (15%). As in the previous set, messages consist of tweets or retweets of newspaper publications, but with the addition of personal thoughts (“A bumpy road to Zero! First #Ebola case in wks in #Liberia. Sexual transmission suspected. [link]”), or of completely original and personal messages (“Ebola travels through a man’s sperm for 60 days after he’s been “Cured” and now both patient have been released into the public. This is what I’ve been concerned about.”, “I don’t know how true this is but this wikipedia page says Ebola can be spread via semen by men who survive it”). Information dissemination becomes an opportunity to express one’s opinion.

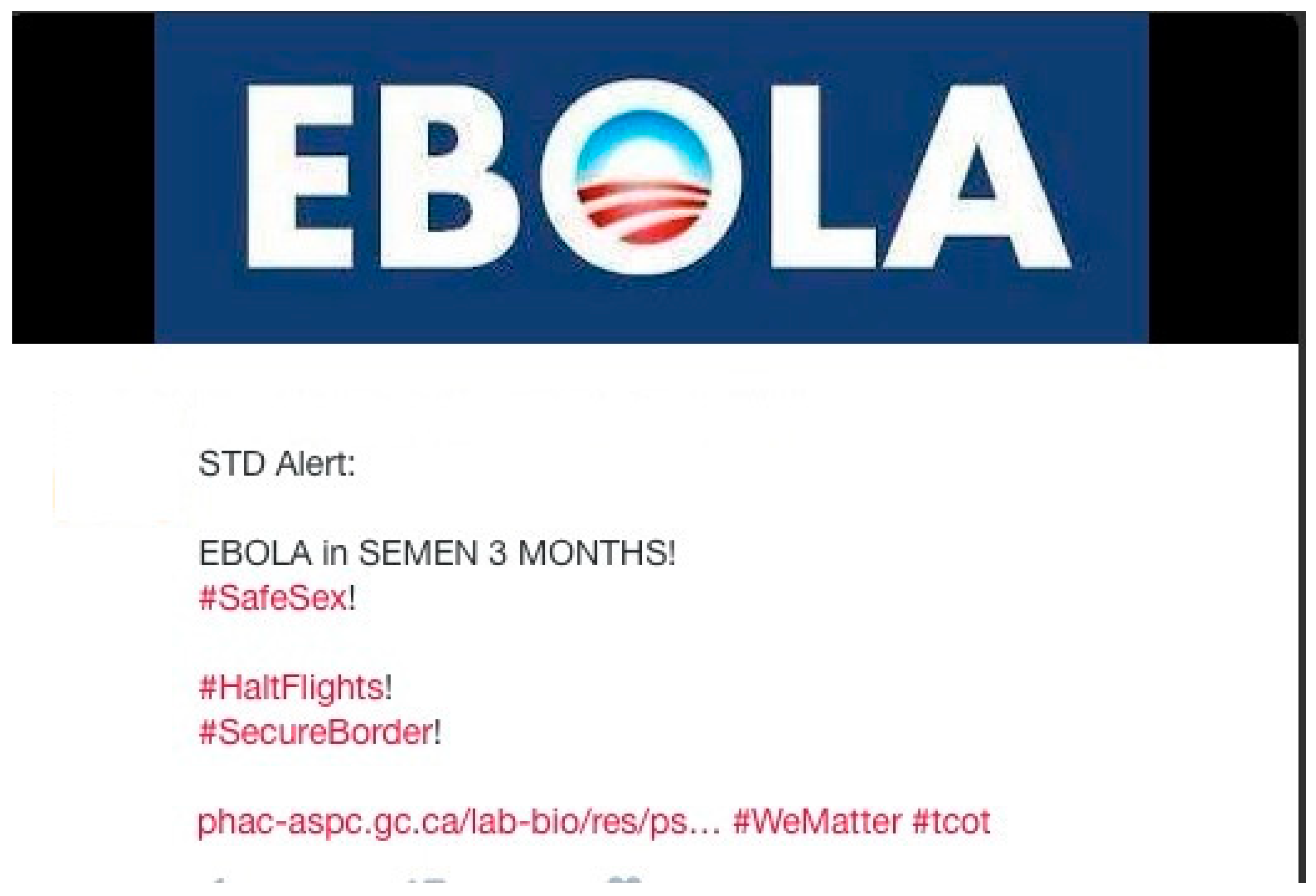

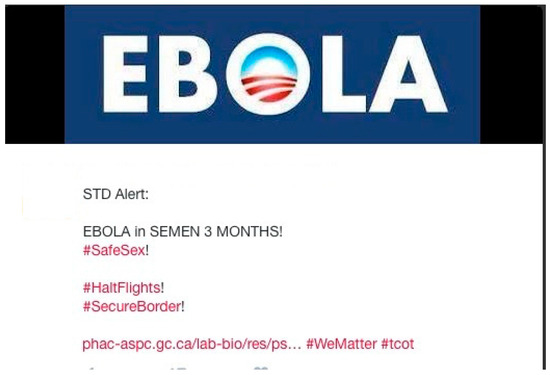

Visuals have a significant importance in lending credibility to discourses. Often, images are taken from official sources (poster, newspaper article, flyer, excerpt from a website, etc.), from public health agencies or from online encyclopedias and accompany a text that is not related to the content of the image. These images are shared by users who wish to engage with the debate on modes of transmission, sometimes with an ideological perspective (“How come no one has announced to the public that male semen can pass on the #Ebola 6 weeks–6 months after recovery”). A polemical use of Twitter appears in a graphic montage where “Ebola” is written with the letterings of the 2008 Barack Obama campaign (Figure 9), the “O” making a strong link between Obama and Ebola. The author of the tweet indicates his or her support for the Tea Party in the accompanying hashtags, therefore seeking to politicize the management of the disease.

Figure 9.

“Ebola” written with the letterings of the 2008 Barack Obama campaign.

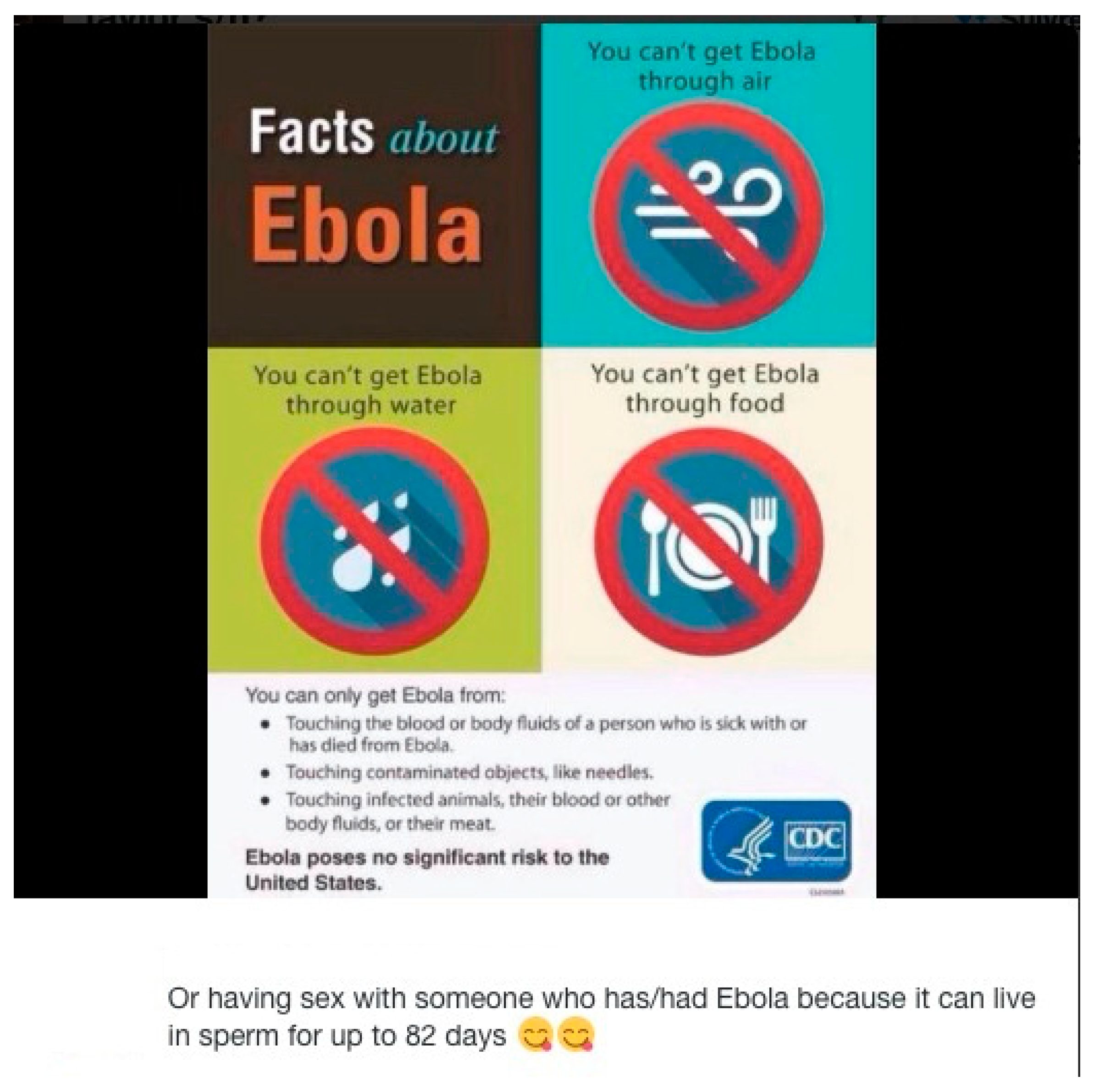

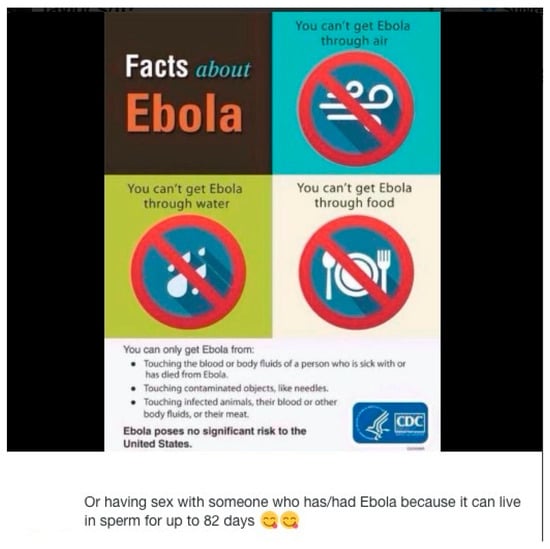

These tweets focus on fear, prevention, and reassurance, and with Ebola’s modes of transmission. While tweets from the first set display unilateral rhetoric, tweets from the second set are more dialogical, and reappropriations of images are widespread, as can be seen in the semantic variations of a specific image. The CDC prevention poster “Facts about Ebola”, which states that Ebola is not transmitted through air, water or food and that “Ebola poses no significant risk in the United States”, is used to convey several different meanings. Some tweet authors laugh at transmission via semen (Figure 10), commenting that “Ebola can be transmitted through semen lol” or “Or having sex with someone who has/had Ebola because it can live in sperm for up to 82 days [followed by two tongue-out emojis]”.

Figure 10.

Laughs at transmission via semen.

Others share this prevention poster to reassure people: “to everybody who is freaking out about Ebola”, “on the real for everybody who is freaking out about Ebola”, “for all you folks worrying about #ebola, read this. Stay away from sweat, poop, blood, semen & pee of others.” A similar CDC prevention poster explaining how the Ebola virus is transmitted (“bodily fluids”, “objects contaminated” and “infected animals”) triggers this commentary: “Here is how you can get Ebola. Sounds similar to AIDS…. Hmmmmm….#conspiracyhat #on.” Images whose original purpose is preventive end up supporting other meanings, such as humoristic content or conspiracy theories.

3.3. Fear and Reassurance in Tweets: The Crucial Role of Images for Dramatizing and De-Dramatizing

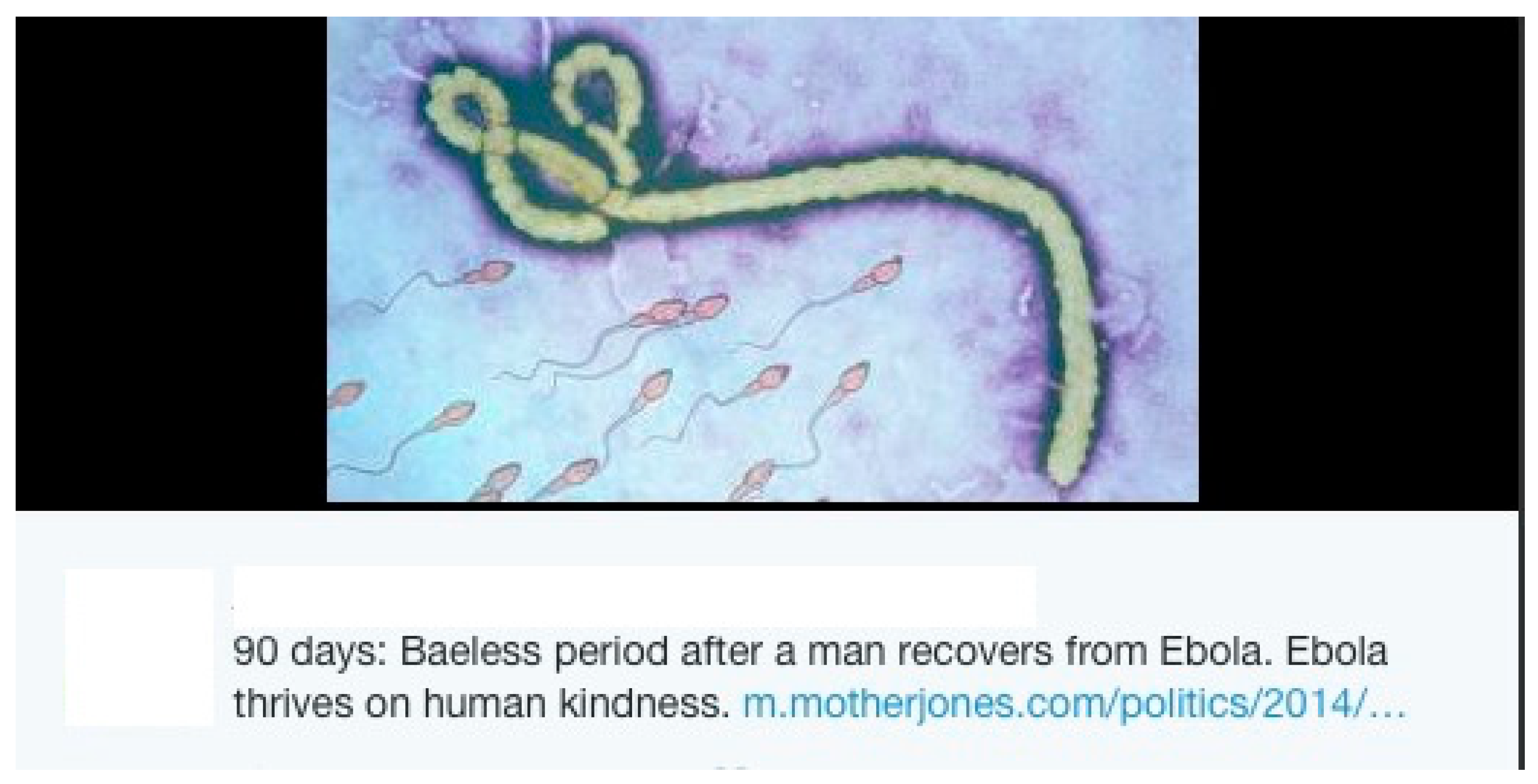

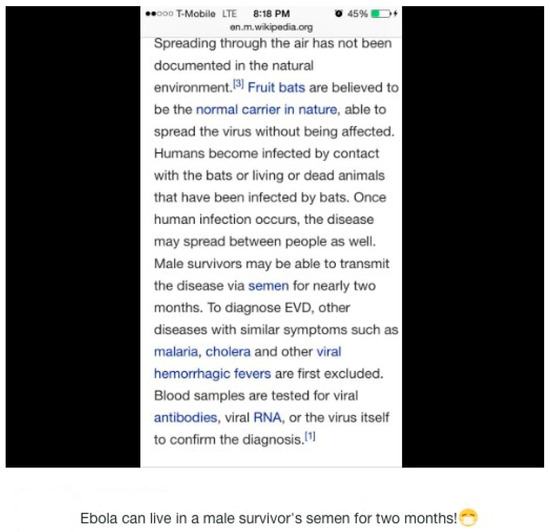

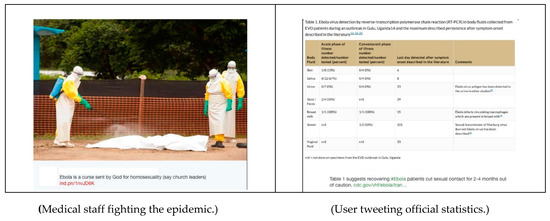

A large proportion of tweets (38.8%) are related to fear, whether they express various fears or serve to scare others, or they relativize the danger and offer reassurance regarding the low risk of contracting Ebola. When fear arises in discourses on the sexual transmission of Ebola, tweets follow the same pattern. Texts mostly share the information (“Research shows Ebola can be found in survivors’ semen for weeks or months after recovery”, “90 days: Baeless [sic] period after a man recovers from Ebola”), sometimes adding emphasis on the concern such news evokes (“It’s possible that Ebola can be sexually transmitted. More on the scary news here.”) or eventually taking a political stance on closing borders (“STD Alert: EBOLA in SEMEN 3 MONTHS! #SafeSex! #HaltFlights! #SecureBorder!”). In juxtaposition with such texts, images firstly show symptoms: The sharing of frightening images, particularly of blisters, evidently aims to illustrate how aggressive the virus is. Secondly, screenshots from online encyclopedias (Figure 11) are used to support what is hard and maybe difficult-to-believe news (“Yu can get ebola thru unprotected sex from what im reading”, “Ebola can live in a male survivor’s semen for two months!” accompanied by a Mask Face emoji).

Figure 11.

User commenting on online encyclopedia.

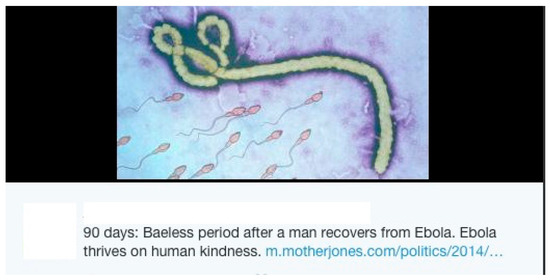

Thirdly, microscopic images of the virus are common, often complemented by texts that are themselves stylistically full of imagery. Many tweets personify Ebola (Figure 12), for example describing it as “AIDS on steroids” or confer on it intentional and almost strategic actions (“Ebola thrives on human kindness”), making it an active subject of the pandemic. A photomontage initially published by American magazine Mother Jones but retweeted since without the corresponding article shows spermatozoa heading towards the virus as if they were about to fertilize it.

Figure 12.

Personification of Ebola.

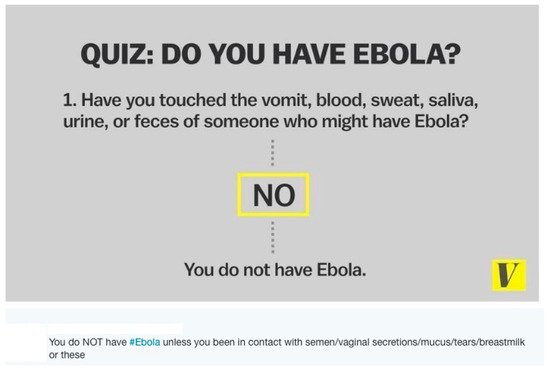

While fears are represented in images shared on Twitter, reassurance and relativization discourses emerge through reappropriations of official posters. Users in our sample mostly shared CDC’s prevention posters or a semihumoristic infographic published by the American news website VOX, asking: “Have you touched the vomit, blood, sweat, saliva, urine, or feces of someone who might have Ebola?”, offering “no” for an only answer and ending with a terse “You do not have Ebola.” Tweets in turn emphasized the fact that “you do NOT have #Ebola” enjoined people to calm down or insisted on the low contagiousness of Ebola (“Worried about your chances of getting Ebola? Here’s a concrete guide on how it spread”), sometimes by putting symptoms into perspective (Figure 13) (“Feeling flu-ish? You don’t have Ebola”).

Figure 13.

Tweet emphasizing the low contagiousness of Ebola.

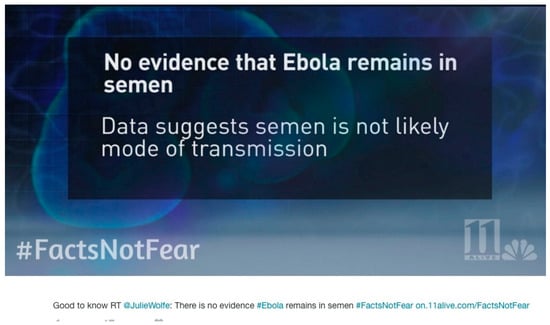

At the same time, information texts within those reassuring tweets (Figure 14) are contradictory, with some users advising people to stop fearing Ebola and to “just use a condom”, while others stated that “there is no evidence #Ebola remains in semen #FactsNotFear.” Users strategically backed their recommendation with images borrowed from legitimate sources, such as the CDC. In fact, not only did tweets calling for calm use prevention posters to legitimate their discourses but, more generally, prevention posters were only shared to support those discourses. However, reassurance is not always expressed in an attentive and comprehensive mode but rather in a biting and sometimes quite aggressive manner. Directly addressing other people’s fear (“for all you folks worrying”, “worried about your chances of getting Ebola?”, “don’t panic about Ebola”, “On the real for everybody who is freaking out about Ebola”), tweets emphasized the actual modes of transmission to call for “facts, not fear” as one hashtag puts it, to ask people to stop panicking about Ebola (“Don’t panic about Ebola, know the facts”) or to mock the fear of Ebola (“Have you be reveling in someone else’s feces, vomit or semen lately? Do they have #Ebola? If NO and NO, chill.”). Discrepancies between what are considered as “real” risks and perceived risks are treated with irony.

Figure 14.

Example of a reassuring tweet.

Images appear to be a major vector for discourses of fear and reassurance (Figure 15). A division can be identified between the kinds of images that are shared depending on these ends. Fear is expressed via visuals that present themselves as “real” (medical staff fighting the epidemic, corpses, sick people, or symptoms), while reassurance discourses use official posters, infographics or screenshots of online encyclopedias.

Figure 15.

Fear via visual, and reassurance discourses via infographics.

These are hybrid images containing texts, and users emphasize they are presenting “facts”. The official character of public health institutions is a main asset, particularly for users engaged in this kind of dialogue against people they characterize as too easily afraid.

These results would not have been found if it were not for a simultaneous analysis of text and image. During the early development of this study, the analysis of only the text in tweets showed that Twitter was not just a place of contestation, information or interrogation, but also a place where expressions of concern were frequent. With the additional analysis of images, however, those results were more nuanced, since it revealed more clearly the presence of fear in tweets. Images such as Hazmat suits, military personnel in action, quarantines or dead bodies construct a semiotics marked strongly by anxiety. Confirming that signs of fear tend to be contained in images rather than text, little repetition was found between text and image in those tweets.

4. Discussion

The study of the articulation “image–text” as used by Mitchell [28] is crucial to a more holistic approach to Twitter itself but calls for specific developments. The objective here is to understand the argumentative or illustrative functions that Twitter users give them. The four kinds of interaction identified by this paper (illustration, commentary, repetition, and complementarity) show how varied and complex text–image relationships are, and how greatly this variety and complexity influence the production of meaning online. While the illustration category was the most likely to aggregate relatively homogeneous texts and images, further analysis revealed significantly different framings of the subject, sometimes even contradictory ones, e.g., the insistence on the preservation of the social links and the necessity of Hazmat suits, quarantines, and containment. Furthermore, our analysis of text–image interaction shows that users deliberately take advantage of online information dissemination to express their points of view by strategically using visuals to lend credibility to their discourses. Twitter is not only a major sphere for information dissemination or for self-expression nowadays: These two functions appear to be interrelated.

If our analysis had covered only text or only images, the results would have been different. A quantitative selection of tweets based only on keywords would have missed important discursive practices online: Only a mix of quantitative and qualitative analysis could identify these, based on manual selection, coding, and interpretation and on successive comparisons between the sources and the corpus. Our findings highlight the interdependence of the text and images online and the semiotic significance of images in supporting a point of view or expressing an emotion and show that for both the traditional media and Twitter users, images play a major part in the expression of fear or reassurance. Official posters are instrumentalized for other purposes than information dissemination. More broadly, our analysis provides original insights into how discourses are built in social media via text–image combinations.

Methodologically speaking, it is limiting to consider text and image separately, firstly because images are not only iconic representations: More than 55% of images do not contain any text, while 19% contain only text without any iconic representation, the remainder being a mix of iconic representation with text. Moreover, our analysis of text and image together shows how dependent meaning is on this relationship: Visuals express discourses of fear or insistence on affection that could not be expressed this strongly in the text area, particularly in the case of the sharing of newspaper articles whose titles are more neutral. In these cases, images are useful for expressing emotive positions. At the same time, visuals themselves are polysemous, calling for a pragmatics of text–image combinations: The strategic reappropriation of official images for making personal discourses more credible is a development that surely evades the control of the authorities that designed these visuals.

This study has certain limitations. No demographic or location information concerning the users could be gathered. The huge number of humoristic images contained in the original data collection biased the corpus so much that we were forced to remove them. A methodology specifically adapted to take humoristic texts and images into account could result in an exploitable corpus that would surely give valuable insight into the spectrum of meanings produced on Twitter. Similarly, further research would benefit from a comparative analysis of different social media platforms highlighting various types of discourses and rhetorics depending on the offered features.

Beyond those limitations, this case study on health in times of humanitarian crisis opens the way for new perspectives of research, methodological as well as theoretical, regarding social media.

This new attention to text–image relationships contributes to better understanding of discursive strategies on Twitter: It shows how users reappropriate a restrictive platform by twisting the uses of images, allowing themselves to emphasize the text, to override the constraint of number of characters, or to format the text in a way that the text box alone would never allow them to do. Users do not mechanically accept the devices the platform offers. What is at stake is a new, comprehensive approach to the rhetorics of users that is specific to Twitter: Its non-optional asynchronous dialogue encourages users to make their messages noticeable and striking. To this end, text and images as well as text–image relationships are not distinct components of online messages but are strategically employed by users as simultaneous elements of the discourse they are trying to elaborate.

This, in return, means that the process of signification using social media needs to be rethought: Content enhancement and dialogism through images have a bearing on Twitter’s use as a public sphere such as credibilization of discourses or politicization of events. Taking text and image into account together promises to shed new light on Twitter’s devices, contents, and uses by allowing them to be better understood not only by themselves, but first and foremost in their articulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization was led by all three authors on an original idea of A.M. C.M. developed the methodology, conducted the analysis, and wrote most of the first draft of the article. A.M. helped conduct the methodology and analysis and wrote consequent portions of the first draft. L.A.-D., who obtained funding acquisition for this research, considerably helped review and edit the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by INSERM / IMMI (Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research / and Institut de Microbiologie et Maladies Infectieuses, the Institute of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Murthy, D. Twitter: Microphone for the masses? Media Cult. Soc. 2011, 33, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, T.; Stronkman, R.; de Vries, A.; Paradies, G.L. Towards a realtime Twitter analysis during crises for operational crisis management. In Proceedings of the 9th International ISCRAM Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–25 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vis, F.; Faulkner, S.; Parry, K.; Manuykhina, Y.; Evans, L. Twitpic-ing the riots: Analysing images shared on Twitter during the 2011 UK riots. In Twitter and Society; Weller, K., Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Mahrt, M., Puschmann, C., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Kharroub, T.; Bas, O. Social media and protests: An examination of Twitter images of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. New Media Soc. 2015, 18, 1973–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, E.K.; Jean, N.S.; Kramer-Golinkoff, E.; Asch, D.A.; Merchant, R.M. The content of social media’s shared images about Ebola: A retrospective study. Public Health 2015, 129, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthes, R. Rhetoric of the image. In Image, Music, Text; Heath, S., Ed.; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hochman, N.; Schwartz, R. Visualizing instagram: Tracing cultural visual rhythms. In Proceedings of the workshop on Social Media Visualization (SocMedVis) in Conjunction with the Sixth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM–12), Dublin, Ireland, 4–7 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, D.; Gross, A.; McGarry, M. Visual Social Media and Big Data. Interpreting Instagram Images Posted on Twitter. Digit. Cult. Soc. 2016, 2, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifentale, A.; Manovich, L. Selfiecity: Exploring photography and self-fashioning in social media. In Postdigital Aesthetics; Berry, D., Dieter, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, M.J.; Baker, S.A. The selfie and the transformation of the public–private distinction. Inform. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappavigna, M. Social media photography: Construing subjectivity in Instagram images. Vis. Commun. 2016, 15, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel O’Donnell, N. Storied lives on Instagram: Factors associated with the need for personal-visual identity. In Proceedings of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication National Conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 4–7 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Gil de Montes, L.; Valencia, J. Understanding an Ebola outbreak: Social representations of emerging infectious diseases. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilman, S.L. AIDS and Syphilis: The Iconography of Disease. October 1987, 43, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, J.M.; Hensel, B.; Schnoring, K.T. Is Twitter a forum for disseminating research to health policy makers? Ann. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papacharissi, Z.; de Fatima Oliveira, M. Affective news and networked publics: The rhythms of news storytelling on #Egypt. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarron, E.; Serrano, J.A.; Wynn, R.; Lau, A.Y.S. Tweet Content Related to Sexually Transmitted Diseases: No Joking Matter. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.; Mart, A.; Moreland-Russell, S.; Caburnay, C. Diabetes topics associated with engagement on Twitter. Prev. Chron. Dis. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heverin, T.; Zach, L. Microblogging for Crisis Communication: Examination of Twitter Use in Response to a 2009 Violent Crisis. In Proceedings of the 7th International ISCRAM Conference, Seattle, DC, USA, 2–5 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Love, B.; Himelboim, I.; Holton, A.; Stewart, K. Twitter as a source of vaccination information: Content drivers and what they are saying. Am. J. Infect Control 2013, 41, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Castaneda-Hernandez, D.M.; McGregor, A. What makes people talk about Ebola on social media? A retrospective analysis of Twitter use. Travel Med. Infect Dis. 2015, 13, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odlum, M.; Yoon, S. What can we learn about the Ebola outbreak from tweets? Am. J. Infect Control 2015, 43, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazard, A.J.; Scheinfeld, E.; Bernhardt, J.M.; Wilcox, G.B.; Suran, M. Detecting themes of public concern: A text mining analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Ebola live Twitter chat. Am. J. Infect Control 2015, 43, 1109–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. The medium and the message of Ebola. Lancet 2014, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, S. Hot crises and media reassurance: A comparison of emerging diseases and Ebola Zaire. Br. J. Sociol. 1998, 49, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, R.; Salway, A. A System for Image-Text Relations in New (And Old) Media. Vis. Commun. 2005, 337–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.; Haarhoff, G. Representations of far-flung illnesses: The case of Ebola in Britain. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchel, W.J.T. Picture Theory. Essays on Verbal & Visual Representation; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).