1. Introduction

This essay analyzes and syntheses key theories and concepts on neighborhood change from the literature on anchor institutions, university engagement, gentrification, neighborhood effects, Cold War, Black liberation studies, urban political economy, and city building. To deepen understanding of neighborhood revitalization and the Columbia University experience, the literature analysis was complemented by an examination of the New York Times and Amsterdam newspapers from 1950 to 1970. The intent was to deepen understanding of the strategies universities used to “revitalize” their host neighborhoods and to gain insight into why these “revitalization” strategies chronically produced undesirable outcomes. Town and gown is a phrase often used to describe the relationship between universities and their host community; throughout this essay, the “town and gown” phrase is used interchangeably with university–host community relations. During the post-war era, it is theorized that break-up of the colonial world combined with the dynamics of a rising knowledge economy to catalyze the Cold War, the Second Great Black Migration, the contemporary Black liberation movement, and the building of the knowledge city. The interaction among these socioeconomic factors fundamentally changed the context in which universities grew and developed.

In this new setting, university leaders, in partnership with local government and the private sector, used an urban renewal strategy, along with a market-driven model of neighborhood development to recreate the

university neighborhood. In this approach, the market is allowed to develop unfettered, while placing profit-making and university expansion over the needs of low-income residents. This method of recreating the university neighborhood produced undesirable results [

1,

2,

3]). The Black urban rebellions of the 1960s and the Black revolutionary activities on campuses in the 1970s interrupted this university-led neighborhood revitalization strategy [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Later in the 1990s, now operating within the engaged university framework, higher education institutions implemented a similar, yet more comprehensive, but equally flawed market-driven model of neighborhood revitalization [

10,

11]). The essay concludes by arguing that to realize its potential, the engaged university must learn from past mistakes and implement, what we call, university engagement “3.0.” The “3.0 movement” seeks to build the

neighborly community by integrating physical and social development, placing people above the market, and infusing nonmarket elements into market dynamics so as to moderate and reduce its undesirable effect on neighborhood development [

1,

2,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

2. Universities and Neighborhood Revitalization Strategy

Universities and other higher education institutions are increasingly viewed as examples of place-based anchors, and are assumed to offer expertise and fiscal support to “revitalize” their host neighborhoods [

17,

18,

19]). In the United States, more than half of all universities are located in central cities, and a growing number of them are engaged in some form of physical neighborhood intervention, including both public and private institutions [

10]. The interest in residentially upgrading the

university neighborhood is supposedly driven by “enlightened” self-interest—an ethos based on the institution’s rootedness in geographic space and its public service mission [

20,

21,

22,

23]. The “enlightened” self-interest philosophy is premised on the notion that a neighborhood’s physical and socioeconomic conditions will positively or negatively affect the university’s reputation and ability to attract students and faculty [

10,

24,

25,

26]. The concept of “enlightened” self-interest, then, is a pragmatic ideal that believes that universities will serve their own interests by acting in the interest of their

university neighborhood [

22,

27,

28]. By building on the ideas of the educator Ernest Boyer and historian Ira Harkavy, the former Secretary of the U.S. Office of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros explained the principle of “enlightened” self-interest this way;

Our Nation’s institutions of higher education are crucial to the fight to save our cities. Colleges and universities must join the effort to rebuild their communities, not just for moral reasons but also out of enlightened self-interest. The long-term futures of both the city and university in this country are so intertwined that one cannot—or perhaps will not—survive without the other. Universities cannot afford to become islands of affluence, self-importance, and horticultural beauty in seas of squalor, violence, and despair.

This concept of “enlightened” self-interest is similar to Michael Porter’s and Mark Kramer’s notion of “shared value”. Porter and Kramer defined “shared value” as policies and practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions of the communities in which it operates. Shared value creation, then, seeks to fashion a symbiotic relationship between a company’s growth and development and a community’s social well-being [

30]. Viewing the host neighborhoods through an enlightened self-interest and shared value lens makes it imperative for Higher-Eds to turn those neighborhoods into great places to live, work, and play [

12,

15,

31]. Within this framework, university-led neighborhood revitalization is conceptualized as a mutually beneficial enterprise for Higher-Eds and neighborhood residents. Thus, the creation of a premise that assumes university-led revitalization efforts will benefit all neighborhood residents [

29,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Anchoring this cheerful view of university-led neighborhood revitalization is the idea that engaged universities are a public good and provide a platform with the capacity to transform society [

10,

36]. This strategy assumes that market-driven neighborhood revitalization, accompanied by public school reform, health initiatives, employment training, and the like, will bring about desirable neighborhood change [

10,

36,

37,

38,

39]. This optimistic viewpoint of university-led neighborhood revitalization is not rooted in the already existing realities of town and gown relations [

10,

12,

13,

35,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Neither is this optimistic view of neighborhood revitalization embedded in a clear-cut understanding of market dynamics and the political economy of place [

2,

46,

47]. Consequently, university-led neighborhood revitalization strategies have failed to bring about desirable neighborhood change throughout the post-World War II era [

10,

11,

12].

3. The Changing Context: Rise of the Knowledge City and the University

The ending of World War II unleashed dynamics that changed the urban context shaping town and gown relations. The break-up of the colonial world and the ensuing battles for national liberation gave birth to a new worldwide division of labor. The globalization process allowed for a knowledge economy to emerge among the capitalist core countries, while the burden of industrialization and industrialism fell on the shoulders of the tricontinents of Latin America, Africa, and Asia [

48]. The break-up of the colonial world also triggered a battle between capitalism and socialism to become the dominant global political economy. This clash led directly to a Manichean struggle for world supremacy between the United States and the Soviet Union, a clash that triggered the Cold War [

49]. The resultant age of propaganda and low-intensity warfare not only privileged national security, intervention in wars of national liberation, and centered “communism” as the prime threat to freedom and democracy, but also it sought to project the United States as a citadel of

freedom, and capitalism as a benevolent economy capable of producing the world’s highest standard of living [

5,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

The surging knowledge economy catalyzed a Second Great Migration of Blacks to urban centers, along with a mass homeownership movement and race-based suburbanization. These events combined with the rise of the knowledge city to structure a new urban context in which the university grew and developed. In this new urban context, the need for expansion and the changing demographics of its host community spurred intense conflict between the university and the neighborhoods in which they were embedded [

12,

26,

35,

45,

51,

55,

56,

57]. Rise of the knowledge economy drove the transformation of higher education. Between 1940 and 1970, the U.S. economy transitioned from an industrial to a knowledge economy driven by high-technology, service, education, and real estate [

51,

57,

58]). The knowledge economy not only required a new infrastructure, consisting of office buildings, cultural facilities, and housing units, along with an arterial system to accommodate the automobile and truck, but also it demanded a new generation of workers with more developed intellectual skills, including scientists, chemists, engineers, physicians, financiers, accountants, lawyers, stock brokers, along with a cadre of cultural, clerical, sales, and other white-collar workers [

51,

57,

59].

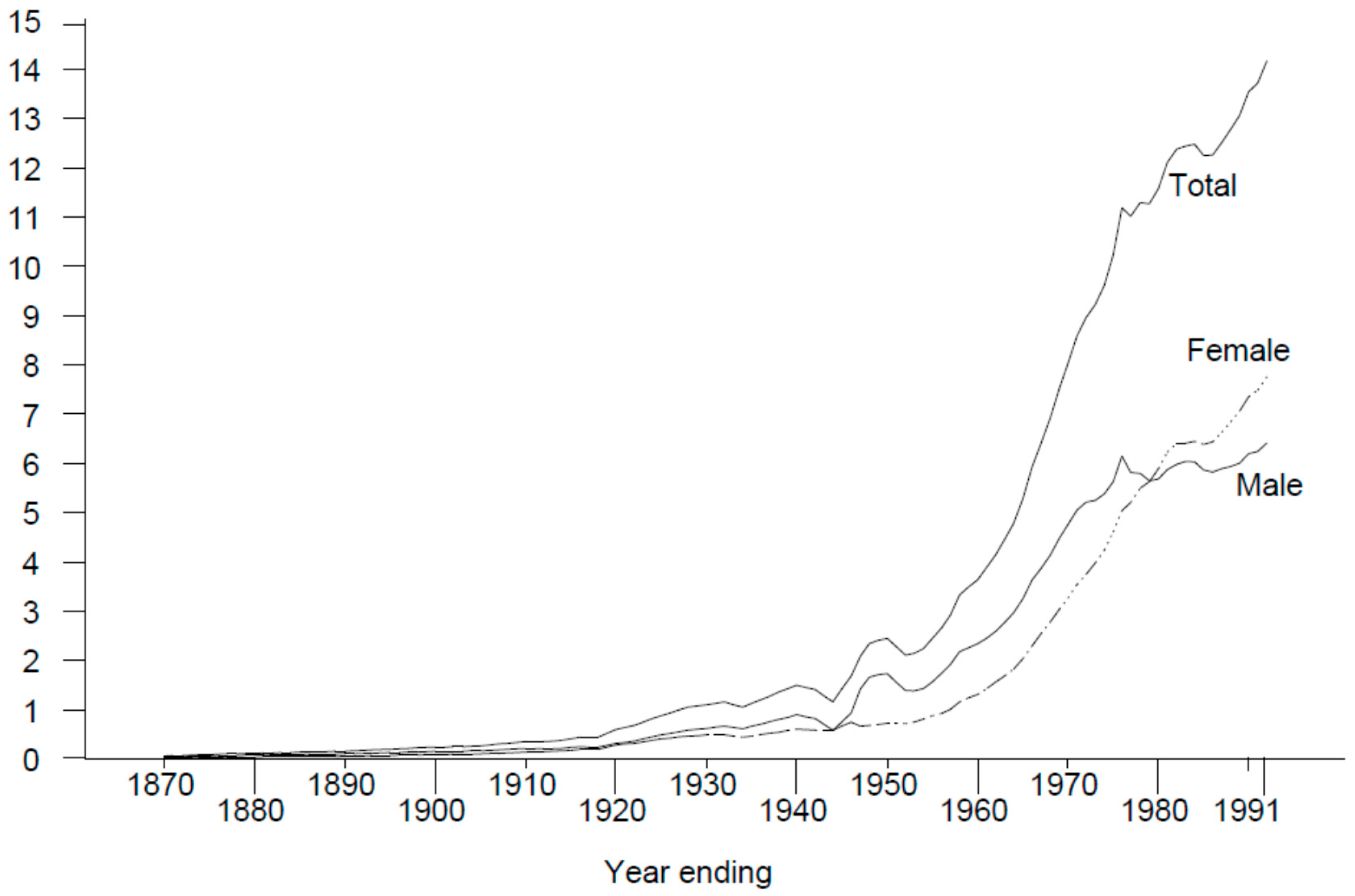

The need for an expanded college-educated elite by the knowledge economy is what ignited the explosive growth of higher education (

Figure 1). Between 1940 and 1980, college enrollment leaped from about 1.5 million to a little over 12 million. This dramatic growth in enrollment led to a corresponding need for more faculty and staff members, as well as new facilities to accommodate the enlarged campus community [

41,

43,

52,

60]. The critical point, however, is that World War II broke up the colonial world, and this gave rise to a globalized economy, which situated high-tech, finance, and service economies in the Western capitalist core country and industrialization and primary industries in the tricontinents [Africa, Asia, and Latin America] [

48,

51]. This new global reality spawned the contest between capitalism and socialism and rise of a Cold War [

50,

61,

62].

Lee Benson and Ira Harkavy stressed the role of big science in the rise of the post-World War II University [

63,

64,

65]. In their view, big science, which included the physical sciences and engineering along with the basic sciences, serviced the Cold War and dominated university life and culture until the Berlin Wall crumbed in 1989. Of course, the Cold War contributed to the development of big science and the growth and development of the research university. The Department of Defense, for example, became the biggest patron of U.S. science, pumped millions into the university system, and the military–industrial–academic complex became a characteristic feature of higher education [

64].

The growth and development of Higher-Eds, however, included more than military contracts and research inspired by national security and overseas adventure [

51,

64]. A synergistic relationship existed among the knowledge economy, the Cold War, research universities, and rise of the knowledge city [

51,

59,

64]. As Cold War investments in research and development grew, state and local economic development policies began to orientate themselves toward attracting high-tech industries and other businesses associated with science and technology, including medical research [

51].

The research university, because of its research capacity and its ability to attract high-tech industries and workers, along with students, faculty, and staff, became a major contributor to economic and commercial development activities associated with Cold War dynamics [

51,

64]. These increased educational and economic activities, in turn, spawned the building of new office buildings, expanded facilities, and new apartment buildings and houses to accommodate this new urban growth and development. The physical requirements of the ascending knowledge economy, including housing and amenities for its larger and more affluent workforce is what spawned rise of the knowledge city [

41,

51,

52,

53,

55,

59,

66].

Big science and Department of Defense Contracts were important to some universities, such as MIT and Stanford, but most universities used the basic and social sciences to power the knowledge economy past the industrial economy. Higher education, then, was a major contributor to the growth and development of the knowledge city and its suburbs [

16,

51,

64]. Vannevar Bush, Director of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, in his 1945 report to the president,

Science: the Endless Frontier, made clear the importance of big science and the new economy.

What we often forget are the millions of pay envelopes on a peacetime Saturday night which are filled because new products and new industries have provided jobs for countless Americans. Science made that possible, too. In 1939 millions of people were employed in industries which did not even exist at the close of the last war-radio, air conditioning, rayon and other synthetic fibers, and plastics are examples of the products of these industries. But these things do not mark the end of progress-they are but the beginning if we make full use of our scientific resources. New manufacturing industries can be started and many older industries greatly strengthened and expanded if we continue to study nature’s laws and apply new knowledge to practical purposes.

Bush’s report identified scientific research as the intellectual driver of innovation and economic development, and it built a bridge between the government and financial support for university-based research [

67,

68]. Our viewpoint complements rather than contest the ideas of Benson and Harkavy. We view the expanding post-war university as a product of the rising knowledge economy. Benson and Harkavy, in their analysis, emphasize big science and its relationship to Cold War dynamics, while minimizing the rise of the knowledge economy [

63]. Our emphasis on the knowledge economy is important because it continued to drive the growth and development of Higher-Eds

after the Cold War ended in 1989.

This knowledge economy also catalyzed the Second Great Migration of Blacks from the south to the northern, midwestern and western cities and the race-based suburbanization movement [

59,

69,

70]. The mechanization of agriculture radically changed labor requirements in southern farming and spawned a mass migration of more than five million Blacks from the south to the cities in the northern, mid-western and western United States, with New York City and Chicago leading the way (

Table 1) [

69,

71,

72,

73]. At the same time, between 1945 and 1970, millions of mostly white students, faculty members, and staff entered the ascending urban universities [

26,

41,

55,

74,

75].

These events took place in a newly emerging

urban metropolis that consisted of a knowledge city and its suburban hinterland [

45]. The influx of millions of mostly low-income Blacks to cities and the dramatic growth of urban universities occurred at the same time that millions of middle-class and higher-paid white workers left the core for suburbia, problematizing metropolitan growth and development [

45,

77]. In this new bifurcated knowledge-based urban context, the knowledge city became the prime location for African Americans, people of color, such as Latinos, poor whites, and the ascending university. In turn, the suburbs became the central setting for middle-class and higher-paid white knowledge workers, the prime location for mass homeownership and for the proliferation of small municipalities [

45,

51,

71]. As a result of the dynamics, the numbers of Black urbanites not only increased, but African Americans also became a much larger proportion of the population. Between 1940 and 1970, Black New York jumped from six percent to twenty-one percent of the population; Black Chicago from eight percent to thirty-three percent, while Black Detroit leaped from nine percent to forty-four percent [

78].

This growing concentration of Blacks in the knowledge city caused the radicals James and Grace Boggs to declare,

the city is the black man’s land in 1966 [

69,

79,

80]. Concurrently, racism combined with city building and structural income inequality to turn

the suburbs into the white man’s land. The growing concentration of high-end owner-occupied housing in the suburbs pulled higher-income white knowledge workers into that part of the metropolis. The knowledge economy [

81], classism and racism, then, transmuted the suburbs and knowledge city into two different places, two separate and unequal parts of the same urban metropolis [

73].

Different city building processes emerged in these two sectors of the metropolis [

82]. Commodification of the housing market spawned a mass homeownership movement and development of the suburbs as

exclusive space; a place where homeownership became a tool of wealth production and market-centric high-end residential development [

83,

84]. Profit-based homeownership became a magnet pulling millions of whites out of the city into the suburbs, while leaving behind a concentration of African Americans in the central core, along with other people of color, and whites who could not, or chose not to leave; and of course, the spatially rooted Higher-Eds. Between 1950 and 1970, for example, New York City’s white population declined by 16% [N = 1,067,600]; Chicago’s by 37% [N = 1,014,758]; and Detroit’s by 59% [N = 706,970]. By 1970, for the first time, more people lived in the suburbs than in the knowledge city. Back in the knowledge city, the story was more complex than the rise of second ghettos, public housing, and fleeing whites. From the urban renewal age onward, black residential space often became contested sites as

growth coalitions, consisting of government officials, urban planners, bankers, realtors, developers, builders, speculators, university officials, and others with an interest in urban growth and land development, prioritized African American communities as sites for highway construction, downtown and institutional expansion, and the development of

chic university-neighborhoods.

4. Building the Knowledge City and the University

Between 1940 and 1980, the surging knowledge economy, driven by high technology, finance, service, real estate, and tourism, supplanted the industrial economy [

57]. The ascending knowledge economy also reconfigured the social order by spawning a new workforce dominated by knowledge workers, including engineers, scientists, chemists, physicians, financiers, accountants, lawyers, architects, teachers, and college professors, along with a cadre of cultural, clerical, sales, and other white-collar workers [

57]. The knowledge economy, then, needed higher education to ramp up its capacity to produce an increased number of college-educated workers. The knowledge economy also required that Higher-Eds use big science to improve existing commercial products and produce new ones. To achieve these goals, higher education needed to recruit more students, faculty, and staff, as well as expand its facilities and campus [

26,

41,

51,

55,

57,

60,

64].

Rise of the knowledge economy thus required

transformation of the industrial city into the knowledge city. A new type of city was needed to accommodate the physical and social demands of the knowledge economy. The knowledge city, for example, needed to house its growing population, to quarter the new and developing cultural establishments, service centers, and educational institutions, especially the university habitat [

51,

85]. In this context, city leaders formed an

urban growth coalition to lead the transformation effort [

52,

66]. The

growth coalition, including university officials, used

urban renewal as a city building tool designed to

recreate the city, so that it could compete with suburbs, accommodate the physical and social requirements of the knowledge economy, and become players into the globalizing economy. Thus, urban renewal was conceived as a strategy to halt and reverse the out-migration of residents, capital, and political power, as well as to expand colleges and universities [

26,

52,

53,

66].

In places such as Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York City, the intent was not only to expand the university to accommodate the influx of students, faculty, and staff, but also to develop a prototype for a

chic university neighborhood that provided residents with an urbane way of life, including a “high-culture” experience [

41,

52]. In this city building and neighborhood model, urban leaders—epitomized by the New York power broker Robert Moses—believed that colleges and universities, museums, art galleries, and hospitals and medical schools should be the cultural and economic engines that drive the new central city’s development [

52,

53,

66].

The knowledge city, in the imaginary of the

growth coalition and university officials, was to function as the hub and cultural center of an urban metropolis based on the knowledge economy. To realize its role, the knowledge city was imbued with a distinctive urban culture and way of life [

41,

52,

85,

86]. New federal legislature provided local communities with the fiscal resources to realize this dream. Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 funded urban redevelopment, giving localities federal money to acquire and clear urban land. The Housing Act of 1954 provided federal funds for both rehabilitating existing structures and clearing slums, and it gave cities the resources needed to recreate and renew the urban core [

52].

5. University Civic Engagement 1.0–Building the University Neighborhood

The combination of urban change and Black migration placed universities and their host neighborhoods on a collision course. Explosive enrollment created the need for universities to expand their facilities. Unfortunately, university habitats were landlocked within their limited spaces and dominated by growing, underdeveloped, and mostly Black neighborhoods [

41]. Within this context, university officials felt threatened by these expanding Black communities, which they conceptualized as blighted and characterized as dangerous. They defined these communities solely by any dilapidated and deteriorating physical structures and by the incidences of crime and violence [

41,

52,

87,

88].

University Officials and the

growth coalition believed the expanding Black and coloured population, the creeping blight, and the decline of their neighboring environment jeopardized a university’s world-class reputation and its assets, along with its ability to recruit students, faculty, and staff. Therefore, university officials, in partnership with the

growth coalition, made expanding its campus and stopping blight the institution’s top priorities [

43,

52,

55]. Also, the university intended to use the urban renewal (and slum clearance) strategy to redefine and re-imagine the

university neighborhood [

41,

55,

56].

The university aimed to recreate and transform the “blighted”

university neighborhood into a racially integrated chic, middle-class community, imbued with an urbane university culture that reflected white knowledge workers, including students, faculty, and staff. The creation of this

chic university neighborhood was part of a larger strategy of building a fashionable, cosmopolitan, and urbane knowledge city, which could compete with the suburbs for people, resources, and customers. The key to building this type of

chic university neighborhood was to

cleanse the community of “undesirable residents” [

89,

90,

91,

92].

The university and

growth coalition did not define “undesirable residents”, but the concept dates back to 19th century efforts to create distinctions between the worthy and unworthy, or the deserving and undeserving poor [

92]. The vagueness of the concept facilitated the ability of urban leaders to identify those low-income groups they felt did not think, feel, or behave like middle-class white Americans [

91]. The dynamics of Cold War politics, however, complicated and problematized this

cleansing task. The Cold War called for the U.S. to project the image of a democratic, free, and racially harmonious nation [

52,

93]. This meant that progressive institutions, such as universities, could not use strong-arm, openly racist tactics to achieve their ends [

52]. Instead, they had to employ democratic and racially neutral methods to seize Black neighborhood lands and to displace “undesirable” population groups [

94].

The experiences of Columbia University and the University of Chicago provide prototypical examples of this approach to recreating the

university neighborhood [

26,

43,

52,

55]. As early as 1946, a consortium of institutions in Morningside Heights, including Columbia University, Barnard College, Union Theological Seminary, Jewish Theological Seminary, Manhattan School of Music, The Riverside Church, and The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, came together to discuss the problem of neighborhood decline and growth of the nearby Black and Puerto Rican populations.

The consortium hired Wilbur C. Munnecke, a social scientist and Vice President of the University of Chicago, to help devise a strategy to tackle the problem of neighborhood decline, blight encroachment, and expansion, and the growing “undesirable” populations. Munnecke argued that past methods of managing the Black and immigrant populations, such as restrictive covenants and southern style racism, were ineffective and undemocratic. Instead, he proposed using a market-centered neighborhood redevelopment strategy that employed tax incentives, mortgage subsidies, and other market tools to attract “desirable” Blacks, while using the slum clearance strategy to uproot and displace “undesirables” [

52].

In July 1947, the consortium led by Columbia University formed Morningside Heights, Inc. (MHI) with David Rockefeller as President and New City Planning Commissioner, Lawrence Orton, as Director of Planning. The intent of MHI was to use a market-centered urban renewal strategy to revitalize Morningside Heights and Harlem. The intent was to declare portions of Morningside Heights and Harlem as blighted, clear the slums, and then recreate the two communities [

26,

32,

43,

52,

55,

95,

96,

97,

98]. The MHI aimed to stem the tide of blight and preserve the neighborhood by using market tools to attract

desirable residents to Morningside Heights and Harlem, including middle-class Blacks, while simultaneously finding innovative means to discourage and displace “undesirable” residents.

David Rockefeller called for the development of a middle-class community based on “interracial living”, and he told a gathering at The Riverside Church, “In a community such as this, where a premium is placed on civil liberties and the rights of man, it should not be an impossible task to make mixed tenancy housing projects profitable and successful ventures” [

52] (pp. 166–167). Some

deserving low-income residents would be allowed to remain in the community [

91,

92]. Toward this goal, Columbia University acquired more than forty-five apartments in Morningside Heights and in neighboring Harlem. They also obtained the right to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park; and in partnership with the city, developed an urban renewal plan that included portions of Harlem [

91,

92]). Columbia intended to use the “gym in the park” as a scheme to erect a barrier between Harlem and Morningside Heights, while simultaneously pursuing a strategy to recreate Harlem as a middle-income “integrated” community [

99].

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Columbia acquired numerous properties to either demolish or convert into student housing. However, the residents of Morningside Heights and Harlem along with their civic and political allies fought back. Tenants waged numerous struggles to keep Columbia from taking over their apartments and displacing them [

43,

96]. In January of 1965, The New York City Commission on Human Rights made public a letter it had sent to Columbia, calling on them to abandon their “reliance on tenant removal as a solution to social problems incidental to its expansion” [

100] (p. 39). The residents won some battles, but lost many others. An arrogant Columbia and the MHI used “hard” strategies, such as getting investors to renovate or construct middle-class housing units, while they demolished deteriorating buildings that led to the displacement of low-income residents; along with “soft” strategies that included crime reduction campaigns and programs to combat juvenile delinquency [

7,

8,

9,

41,

101].

The same goal of recreating the

university neighborhood was happening in Chicago. In 1952, Lawrence Kimpton, the Chancellor of the University of Chicago, established the South East Chicago Commission (SECC) to “combat the forces of uncertainty and deterioration at work in the neighborhood.” Kimpton intended for the commission to fight crime, organize civic involvement by street/block engagement, and to develop a comprehensive plan for the neighborhood improvement. The intent was to maintain and expand the neighborhood’s middle-class population, pursue racial integration, while simultaneously reducing the neighborhood’s low-income Black population [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

102]. The 1956 Hyde Park-Kenwood, Chicago urban renewal plan called for the acquisition and demolition of 630 buildings and an additional 5941 housing units [

56,

103].

6. Section 112 of the 1949 Housing Act

Columbia University and the University of Chicago were not the only institutions of higher education grappling with the problem of expanding, mostly black neighborhoods, creeping blight and the need for expansion. Across the country, numerous urban universities felt their institutions were threatened by similar issues [

41]. The 1949 Housing Act created a mechanism for Higher-Eds to solve this problem. The Housing Act gave cities the legal framework and resources necessary to acquire land and create space within the urban grid for office buildings, along with varied institutional and cultural structures, apartments, and public housing units. Eminent domain made it possible for the government to acquire property, clear the land, and then auction it off to the highest bidder [

54,

89].

The vagueness of the 1949 Housing Act made it possible for the demolition of residential neighborhoods and their replacement with large commercial, residential, or institutional projects. The Housing Act, however, did not specifically include colleges and universities as designated sites for renewal. Yet, from the perspective of university leaders, their schools were islands in a sea of “blighted buildings and dwelling units”, and the Housing Act could provide them with the resources needed to revitalize their communities [

41]. Moreover, university officials believed that vibrant

university neighborhoods could play a critical role in addressing the problem of deteriorating cities and thus identified themselves as critical partners in the quest to build knowledge cities that competed with the suburbs.

In 1957, University of Chicago Chancellor Lawrence A. Kimpton formed and led a coalition of top urban universities, including Harvard, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to lobby the federal government for inclusion of higher education in the 1949 Housing Act [

41,

104]. This effort led to a nationwide study of neighborhoods surrounding universities and in 1957 the American Association of Universities (AAU) announced that it would fund the research. The Association of Urban Universities (AUU) readily agreed to cosponsor this study [

104].

In the

Age of University Civic Engagement 1.0, naked self-interest, rather than “enlightened” interest motivated university officials. Their intent was to recreate the university community as an integral part of a knowledge city. At the AUU’s annual meeting in 1958, Julian Levi, Executive Director of the South East Chicago Commission, argued that

university neighborhoods needed to attract middle-class residents not only to benefit the university but to counteract the city’s decline. Cities, he argued, need universities whose faculty live in and engage with their communities [

41]. They also need the scientific, educational, and cultural institutions that locate themselves adjacent to universities. Paul Ylvisaker, associate director of the Public Affairs program at the Ford Foundation, stated that urban universities had been left behind in neighborhoods growing increasingly less desirable, and that, unless something was done, these institutions would be tempted to join the flight from the city. He argued that urban settings must allow the urban university to realize its purpose and potential and, more importantly, such a plan must be a top priority for city and state officials [

41].

The AAU created a committee to oversee such a study. The committee included the presidents of Columbia, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania. The study aimed to address three problems: (1) the lack of acreage for expansion; (2) the threat posed by crimes committed against students and faculty within the neighboring communities; and, (3) the high costs of addressing these issues. Then, in 1959, the American Council on Education appointed a Special Committee on Urban Renewal to set up an office to assist individual universities in urban renewal projects. As a result of vigorous lobbying, higher education persuaded the government to add Section 112 to the 1949 Housing Act. This section allowed for the availability of federal funds for “urban renewal areas involving colleges and universities” [

41] (pp. 1165–1166 on Kindle). The amendment facilitated the development of a partnership among city government, the private sector, and higher education to rebuild the

university-neighborhood.

7. Interruption of University Civic Engagement 1.0

During the 1950s and 1960s, university officials and the

growth coalition arrogantly moved forward in their quest to halt blight, expand their campuses, and recreate the

university-neighborhood by usurping the lands on which Blacks lived, worked, played, and built their communities. By 1964, the federal Housing and Home Finance Agency reported that 154 urban renewal projects involving 120 colleges and universities and seventy-five hospitals had received Section 112 funds [

41] (pp. 1177–1178 on Kindle). In 1964, Kenneth Ashworth, Assistant Director of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, published an article in the

Journal of Higher Education to explain how universities can use urban renewal as a tool for the “planned growth of their campuses and the improvement of their surrounding neighborhoods.” This tool, he argued, enabled universities to simultaneously improve the neighborhood by removing the adjoining slum areas and expanding their campuses [

105].

As higher education and their hospital partners prepared to intensify their expansionist programs, Black America exploded, spawning the

Age of Long Hot Summers. Between 1964 and 1968, hundreds of Black urban rebellions occurred in cities across the United States and “Burn, Baby, Burn” became a slogan of the surging Black Power Movement [

106,

107]. The radical Black urban revolution and the ascendency of the Black Power Movement changed the urban landscape [

69,

108]. During the Second Great Migration, millions of African Americans who moved to cities were filled with freedom dreams and hope of a better life. Instead, they found slums, unemployment, and hard times in the emerging knowledge cities [

5,

73,

109]. Of course, some Blacks benefitted in this new setting, and incomes did rise for a nascent middle-class, but for the masses, the struggles for survival and the endless battle to build community on somebody else’s land dominated everyday life and culture. “Community control” and “self-determination” became watchwords [

110,

111], and leftist radicals used

neocolonialism to explain the positionality of blacks living in neighborhoods, where land was owned and controlled by outsiders [

5].

Harlem was the spark that started the prairie fire, which spawned the

Age of Long Hot Summers [

112]. The Black poet, Langston Hughes, captured the mood of Black folk in the early 1960s in his poem,

Harlem: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or does it explode? On July 18, 1964, Black Harlem answered this rhetorical question—

the deferred dream exploded. Violence broke out at a demonstration protesting the killing of a 15-year-old boy by a white policeman. That event changed urban America, and interrupted Columbia’s quest to refashion the

university neighborhood, including Harlem [

113]. The Harlem rebellion spread quickly to Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, Rochester, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Jersey City and Paterson, New Jersey [

114]. These events ignited the era of long, hot summers of violent urban rebellions in the United States. Over the next four years, hundreds of urban rebellions occurred as Black Power supplanted the Civil Rights Movement as the engine driving the African American freedom struggle [

108,

115,

116].

Institutional self-interest defined

University Civic Engagement 1.0. In this moment, the intent was to use community engagement, including its neighborhood revitalization component, to halt creeping blight, expand its campus, and transformed the “blighted”

university neighborhood into a chic, urbane, cosmopolitan, and “integrated” enclave dominated by the white middle-class, along with white students, faculty and staff. Angry Black students, in partnership with community residents, interrupted

University Civic Engagement 1.0. Radical Black students at Columbia University wrote the storyline. They united with angry Black parents and residents in a bitter fight against Columbia’s gym in the park strategy [

6]. For years, Columbia ignored the protests of community residents, including Black politicians, but the entry of Black students into the fray created an internal crisis at the university that

interrupted its expansionist aims, complicated its role in metrocity building process, and caused administrators to rethink the way in which they engaged the university community [

3,

6,

8,

9].

8. The Revolution in Higher Education

Revolutionary Black students forced the university to turn inward and address its own racism and sexism. Across the United States, Black students, along with the radical white student movement, changed higher education and paved the way for rise of the

engaged university movement. Black students organized protests on about two hundred college campuses across the United States in 1968 and 1969 and into the early 1970s. Their militant activities combined with the antiwar movement activated white students, and catalyzed an age of rebellion that reformed and profoundly transformed university life and culture [

4,

117]. Collectively, these activities

interrupted the university’s expansionist aims, complicated its role in the knowledge-city building process, caused administrators to rethink their strategy for rebuilding the university community, and sparked rise of the engaged university movement. Thus, the Black revolution on campus was a precondition to the emergence of

university civic engagement 2.0.

The students fought to increase Black enrollment on campus, as well as to recruit Black faculty and staff members. These changes then led to the establishment of Black studies programs and departments at universities across the United States. The first Black Studies Program was established in February 1968, when San Francisco State hired sociologist Nathan Hare to lead it. By 1980, Black studies programs and departments were found on most college campuses [

118]. During this same period, radical women students struggled to develop Women Studies Programs, with the first program being established in 1970 at San Diego State College [

119].

Campus rebellions forged the internal conditions that gave rise to the engaged university and its civic engagement movement, while the ending of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberal economic policies created the external conditions. The ending of the Cold War, as Benson and Harkavy point out, caused policy makers to pose the question, “If American research universities were really so great, why were American cities so pathological?” [

63]. Neoliberal economic policies problematized this question for Higher-Eds. Neoliberalism called for lower taxes, smaller government, and increased privatization. As government dollars dwindled, higher education faced increased competition from other public-funded sections, including primary and secondary education. As the competition for increasingly scarce funds intensified, Higher-Eds needed to find a new and compelling way to explain their status as a public good.

This is where the civic engagement strategy enters the story [

36,

120,

121]. The

age of declining public resources is what gave rise to the engaged university movement during the early 1980s. The founding of the West Philadelphia Improvement Corps (WEPIC) by the University of Pennsylvania, with its comprehensive school–community–university partnership, along with the establishment of Campus Compact, a national coalition of colleges and universities committed to civic education and community development. Two years later, in 1987, the University of Illinois launched its East St. Louis, and the University at Buffalo established the U.B. Center for Urban Studies, under the leadership of Professor Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., to popularize public service on campus and build linkages between the university and the community [

18,

122,

123].

In that moment, Derek Bok [

20,

21], Ernest Boyer [

23,

27,

124,

125] made powerful cases for the university to become engaged in the development of cities. Then, in 1994, Henry Cisneros, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, created the Office of University Partnerships to bolster the growing movement by connecting it to the federal government [

29]. A year later, in 1995, Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., argued that the research university must play a significant role in regenerating underdeveloped neighborhoods [

126]. In 1997, in the

Journal of Planning Literature, Barry Checkoway [

33,

34] argued that research universities should be reinvented for civic engagement. Lee Benson and Ira Harkavy called upon universities to abandon their selfishness and embrace the doctrine of “enlightened self-interest” [

16]. Later, Michael Porter called for universities to create shared value with their campus neighbors. Rather than grow and develop at the expense of the community, they should embrace a strategy to produce shared value for their host community [

30].

Within this context, college presidents increasingly embraced the civic engagement movement, and on some campuses, such as the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, the entire university, including schools, departments, and centres, became involved in civic engagement [

127]. Increasingly, higher education took the lead in regenerating the neighborhoods in which they were located. As they engaged the community, most faculty, staff, and students followed the doctrine of maximum feasible participation among residents in neighborhood-based projects. To create stronger links between research and community activism, scholars developed action-research and community participatory research models to involve neighborhood residents in studies of their own community.

9. University Civic Engagement 2.0

The goal of the

engaged university movement is to re-imagine the university as an engine of progressive social change, to institutionalize

university civic engagement by placing it at the center of university life and culture, and to transform the United States into a social, racial, economic, political, and culturally just society [

15,

31]. The

movement interwove this

lofty goal with the task of transforming the knowledge city and its suburbs into a just metropolis anchored by the

neighborly community [

15,

128,

129,

130]). By

neighborly community, we are referring to inclusive

cross-class neighborhoods with strong institutions, anchored by community control, where Blacks, people of colour and low-income groups live in quality affordable housing, earn a living wage and have access to a range of supportive services, including good schools, quality medical treatment, and food security [

14] (pp. 71–110).

This is the prototypical neighborhood the engaged university movement seeks to build. To realize this task in practice, Lee Benson, Ira Harkavy, and John Puckett says we must radically transform and interconnect

the university,

the public school, and the

neighborhood [

15,

31]. For the university to play its leading role in this social change process, Benson and Harkavy says it must abandon selfishness and embrace the “enlightened” self-interest credo [

15] (p. 104). Nancy Zimpher sought to build such a university while chancellor of the University at Wisconsin at Milwaukee (UWM). Her goal was to engage every one of UWM’s schools and colleges in the institution’s core mission of service to the local community and indirectly to the transformation of underdeveloped neighborhoods into good places to live, work and play [

131,

132].

This broad ideological framework fueled

university civic engagement 2.0, which exploded between 1990 and 2017. Service learning and civic engagement became popular campus activities and legitimate scholarly endeavors on most colleges. On campuses across the United States, most schools and departments incorporated civic engagement into their tenure and promotion process, and faculty, staff, and students were encouraged to work on varied projects in the city and rural areas [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Yet, for the most part, civic engagement has had little or no effect on the structures of racism and social class inequality, while the university’s neighborhood revitalization activities have spawned

residential upgrading, accompanied by displacement, housing unaffordability, and gentrification. In short, the civic engagement movement has not come close to realizing the social transformation goals championed by Ira Harkavy and the engaged university movement [

12].

The reason is why? Involving the entire university in

civic engagement led to a division of labor between the faculty and the administrative. Their collective activities aimed at the “inclusion” blacks on the basis of equality, rather than the “fundamental transformation” of U.S. racist institutions. Moreover, they structured their activities within a market-centered framework of residential development. In this scenario, “soft” activities, such as school reform, health initiatives, environmental activism, food security, and various supportive service activities, fell under the purview of academics, students, and staff, while university officials managed “hard” activities, such as neighborhood “revitalization” and economic development [

12,

18,

32]. While “soft” programs are often driven by progressive ideas, the “hard” strategies tend to be conservative ones driven by pragmatic, market-centric principles. For example, officials that led “hard” initiatives, typically viewed the role of the university as that of real estate developer, purchaser, and workforce developer [

32]. Rhetoric aside, university officials, such as Judith Rodin, the seventh president of the University of Pennsylvania, never embraced the

neighborly community model of community development. Instead, she, along with Nancy Zimpher, adopted a market-driven model of neighborhood development that mimicked the model university officials developed during

University Civic Engagement 1.0 [

32,

90].

This model is driven by market dynamics, class segregation, cultural hegemony, and

cleansing the neighborhood of “undesirables”, mostly low-income Blacks and Latinos. The implementation of this model is turning

university neighborhoods into class-segregated, exclusive residential spaces. The reason is in market-centric approaches,

neighborhood upgrading inevitably leading to increased property values, rising rents, cultural change, and the displacement of low-income renters. The housing cost burden will increase weight on the shoulders of low-income renters, eventually forcing them out of the neighborhood [

32]. The outcomes in market-centered residential development are predictable. As the blocks inside the

university neighborhood were residentially upgraded and grew wealthier, market demand increased. As property values, housing prices and rents increased, the

university neighborhood became whiter, more educated, and more homogeneous. Meanwhile, the happy talk about neighborhoods rebounding masked the gradual disappearance of low-income groups, including Blacks and Latinos [

10].

A range of “soft” civic engagement programs, however, provide universities with good public relations, but nowhere did the “soft” programs alter the structures of racism and social class inequity, and nowhere did they change the life chances of low-income residents [

12,

133]. Ultimately, then,

neighborhood upgrading and gentrification wiped out any gains that might have been derived from “soft” programs, including the public schooling strategies. The neighborhood effects literature make clear the relationship between neighborhood conditions and undesirable socioeconomic outcomes [

19]. The bottom line is that universities adopted a “throw-back”, market-driven neighborhood revitalization strategies, which

undermined the desirable effects of

University Civic Engagement 2.0.

The University of Cincinnati provides a classic case study of such an approach to market-centered revitalization of

university neighborhoods. During her days in Milwaukee, Nancy Zimpher called for the building of a new type of university informed by civic engagement, but at the Universality of Cincinnati (U.C.), she viewed civic engagement through the lens of university self-interest and market-driven neighborhood revitalization. Like many urban universities, U.C.’s campus neighborhoods, especially Clifton Heights and Corryville communities, were considered disfigured, undesirable, and dangerous. University officials believed that the declining neighborhoods endangered assets and jeopardized their ability to attract quality students [

10,

26].

The university thus embarked on a revitalization strategy to make the

university-neighborhood more attractive A UC alumnus and local realtor, Andy Morgan, told Zimpher, “The secret [

neighborhood revitalization] is to get rid of the trash and get rid of the people in the area who are not there for any academic reasons, or are not productive members of society. This may sound harsh…But it is the truth…” Changes to the physical environment alone would not make students feel more comfortable, he said. “I have had hundreds of contacts over the years with parents, both black and white”, he wrote, “and the number 1 issue is their children’s safety” [

90] (p. 247).

Morgan, then, argued that the University of Cincinnati had to

cleanse the neighborhood of “undesirables” to recreate and make it a safe place to live, work, and study. This, in his viewpoint, was the only way to build a community where students and employees felt safe and comfortable [

90], (p. 247). The University of Cincinnati was not alone. Around the country, Higher-Eds used this and similar market-centered strategies in their revitalization efforts. Everywhere, the low-income renter class, Blacks, Hispanics, immigrants, refugees, and whites, were the most vulnerable populations, and the ones most likely displaced from the university community [

10,

11,

19].

University Civic Engagement 2.0 has not moved the engaged university movement closer to the creation of a new type of university, nor has it moved it closer to building the

neighborly community.

Civic engagement 2.0 did mitigate some harmful conditions, but it has yet to solve the core problems facing Blacks and people of colour—the human rights issues of unemployment, low-incomes, inadequate education, poor housing, insufficient health, food insecurity, and underdeveloped neighborhoods. Nor has the movement changed fundamentally systemic structural racism and social class inequality [

17]. Instead, it has mostly attacked symptoms of oppression and exploitation, while leaving their root causes untouched. Even so, as Ira Harkavy repeatedly says, “the university is our best hope for realizing a truly democratic and cosmopolitan society” [

134]. Harkavy is right, and in the remaining section of this essay, we will outline a strategic approach to the development of a new movement,

university civic engagement 3.0.

10. Toward University Civic Engagement 3.0

Given the realities outlined above, the primary task of the

engaged university movement is to build on the lessons of the earlier period and launch

university civic engagement 3.0. This task centers the transformation of distressed and underdeveloped neighborhoods into

neighborly communities, while it seeks to turn “gentrified”

university-neighborhoods into authentic

neighborhood communities. To design and build this type of inclusive neighborhood requires creation of a dynamic relationship among the

university,

public schools, and the

neighborhood. Within this framework, the radical transformation of the neighborhood’s physical environment must be centered [

15,

31].

The neighborhood effects literature makes it clear that you cannot change the realities of low- income groups without transforming the physical settlements in which they live, including the development of high-quality affordable rental units [

135,

136]. Toward this end, school reform must be linked to the neighborhood transformation process, and ultimately become one of its driving forces. In this interactive relationship, the university must embrace the “enlightened” self-interest credo and use its vast human and fiscal resources to partner with the “community”, especially its low-income residents [

137,

138]. In this approach, a people-centered model, which places social needs above profit-making, must drive the neighborhood transformation process.

Market dynamics will distort, thwart, and upend the quest for neighborhood-based equity, inclusiveness and social justice. When unleashed, market dynamics will create income and cultural homogeneity by spawning increases in property values, housing prices, and rents and by catalyzing the development of chic retail and commercial activities, while eliminating services that target the poor. These forces will undermine the

neighborly community concept by displacing low-income residents, especially Blacks and Latinos. Therefore, the

market must be regulated and controlled when building inclusive, socially just neighborhoods, characterized by class and race mixing [

2]. In the remainder of this section, we will outline four fundamental principles that should guide development of the

neighborly community [

1,

14].

11. Building the Neighborly Community

The first principle is that neighborhood development should be a resident-driven process that occurs at the neighborhood scale, with carefully delineated boundaries established. Although the university and other stakeholders must participate in the redevelopment process, it should nevertheless be controlled by the people who live in the community, with the interest of low-income groups protected. The “community” is a class-stratified place, with tensions often existing between stakeholders, property owners, homeowners and low-income renters. The reason is that property owners, as well as stakeholders, are driven and/or influenced by exchange value, while the actions of renters are driven mostly by use-value [

2]. Hence, there are instances in which homeowners are willing to sacrifice the “interest” of low-income residents in quest of increased property values. The interest of the most vulnerable population groups in the neighborhood must therefore be protected [

13].

The second principle is that comprehensive neighborhood planning must guide the neighborhood redevelopment process. The task is not just to redevelop the neighborhood but to redesign and recreate it. This will happen only if the neighborhood development process is driven by a comprehensive planning process that integrates the physical and social development of the community. The radical planning process seeks to solve complex and complicated problems related to housing and urban landscape issues, including pollution, vacant lots, poorly maintained housing, and abandoned structures, as well as social development questions related to schooling, the delivery of health care services, food security, and social supports. The plan should thus outline a transformative strategy that interweaves the physical and social dimensions of the stratagem into a single fabric, anchored by three interactive components:

housing,

neighborhood development, and

people [

139].

The third principle focuses on people-centered neighborhood development. Building the neighborly community requires infusing the market with people-centered development strategies that

weaken market dynamics by using mechanisms that regulate and control it. The need for such controls is simple. Without them, during residential upgrading, market dynamics will catalyze residential changes that will lead to cultural change and the displacement of low-income renters and homeowners. The community land trust (CLT), in this context, despite the challenge of using it effectively, remains our best hope for ensuring that equitable, inclusive, and socially just neighborhood development occurs in the

university neighborhood [

140].

The central idea is to take a significant portion of community land out of the market domain, so that social needs and desires are placed over profit-making schemes. In this approach, the intent is to promote communal ownership over private ownership and to conjure up a culture that values collaboration, cooperation, and collectivism. The

neighborly community concept then stresses community participation, social democracy, communal landownership, collective ownership, and

shared equity. This

shared equity value is an addendum to the private property ideal, and it is designed to construct a setting that facilitates the participation of low-income groups property ownership and that increases their control over neighborhood dynamics [

94,

141,

142,

143].

The CLT is a private, non-profit corporation that acquires and retains ownership over plots of land. It typically maintains ownership of the “land”, while selling structures on the land, including houses and apartment buildings [

40]. The CLT is controlled and managed by the community, with every resident entitled to membership and participation in the land management process. CLTs market their houses to low- to moderate-income households and often sell homes or rent apartments at below-market rates to keep them affordable. CLTs can also work with developers to build apartment units, or acquire existing structures, which are then rented to low-income residents. The important issue is that the CLT gives residents ownership and control over the development of neighborhood communal lands. In the

neighborly community framework, when developing communal lands, the interests of the most vulnerable residents must always drive the process. While the CLT is mostly concerned about using communal lands to ensure the existence of high-quality affordable housing for low-to-moderate-income households, it can also pursue other retail and commercial usages designed to enhance the quality of neighborhood for residents [

144].

The

neighborly community strategy not only emphasizes the communal ownership of land, but also stresses the value of collective forms of ownership. Shared equity homeownership, for instance, is a viable complement to traditional home ownership or rental choices in the United States, and it includes limited equity cooperatives (LECs), deed restricted houses and condominiums with permanent affordability convents [

145]. LECs are legal corporations that are formed when people come together to own and control the building in which they live. The cooperative owns the land, building, and community areas, while the member-owners own a share in the cooperative. Members live in and run the cooperative—from organizing social activities to maintenance to handling financing and landscaping. They set the bylaws and elect a board of directors, in much the same way as a CLT. In deed-restricted housing, the real estate is transferred from one owner to another by a deed, with a covenant that places limitations or restrictions on how the real estate is occupied, used and/or sold. Condos are structured in a manner similar to LECs. The intent of communal approach is to extend the powers and benefits of ownership to groups that are typically denied this opportunity, as well as to increase control and ownership of land among low-income and community residents [

145].

The fourth principle is centering the low-income rental housing problem. Solving this problem is complicated by the private sector having responsibility for supplying housing to low-income populations. This problem is made more complicated by a decline in federal investments in public housing and the epidemic of evictions [

135,

146]. The calculus of low-income rental units requires that owners change rents that are sufficiently high to cover the costs of maintenance, upgrades, operations, mortgage, and to generate a profit margin. Property owners often cannot cover these costs, and make a profit, with the rents of low-income tenants; so they cut back on their expenses until they reach an indeterminant threshold where profits can be made. This approach typically leads to deferred maintenance. Time will not permit a full discussion of this challenge, but there are three activities that should be pursued in solving it.

First, neighborhoods should develop an aggressive code enforcement program that forces owners to improve their properties, or lose them. To make this happen, neighborhoods in partnership with local government and a neighborhood-based Community Development Corporation, should establish brigades of volunteer building code inspectors. This is where the connection between school reform and neighborhood development comes in. Neighborhood development programs can be established in local high schools, and students trained to do code enforcement. Second, local government should strengthen their existing housing receivership program, or start one if none exist. In receivership programs, privately owned rental units are placed in “receivership” and the rents are used to bring the properties up to code, after which the property is returned to the owner.

These receivership programs should be connected to a community economic development strategy. For example, neighborhoods should partner with or establish their own community development corporation that has the capacity to do housing repairs and rehabilitation. Youth-Build-type programs could also be established with high schools to provide students with training in home repairs and housing rehabilitation. In this way, students acquire skill training, while participating in the rebuilding of their communities.

Lastly, these types of activities could be funded by repurposing dollars available to most municipalities. For example, the UB Center for Urban Studies recently completed an analysis of expenditures by the City of Buffalo for the 2006–2016 period. During this period, the City spent $179,000,000 in the mostly Black East Side community. An assessment of the federal Community Development Block Grant program demonstrated a spending pattern, which suggests that these dollars could be used to upgrade rental properties and provide rent assistance to low-income families. There were other city resources that could also be repurposed. These are dollars, we stress, which are already being spent in the Black community. However, in Buffalo and elsewhere, we suspect that resources are invested in a random, non-strategic and chaotic manner with a minimal return on investment. If repurposed, and strategically spent, these investments could yield a much greater rate of return on the investment and help solve the low-income rental housing problem.

In conclusion, universities must move beyond happy talk about revitalizing neighborhoods and helping people and launch an enhance strategy to create the engaged university and build the

neighborly community. To achieve this goal, we must adopt redevelopment strategies that

control and

regulate market dynamics, grasp fully the neoliberal economic forces spawning the fiscal constraints facing Higher-Eds, and recognize fully the dangers confronting the engaged university model [

58,

75]. The university maintaining its

engaged university outlook remains central to societal transformation and the recreation of the United States as a people-centered social democracy.