The Impact of Single-Family Rental REITs on Regional Housing Markets: A Case Study of Nashville, TN

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Emergence of Real Estate Investment Trusts

1.2. A Shifting Business Model

1.3. The Need for More Local Research

2. Methods

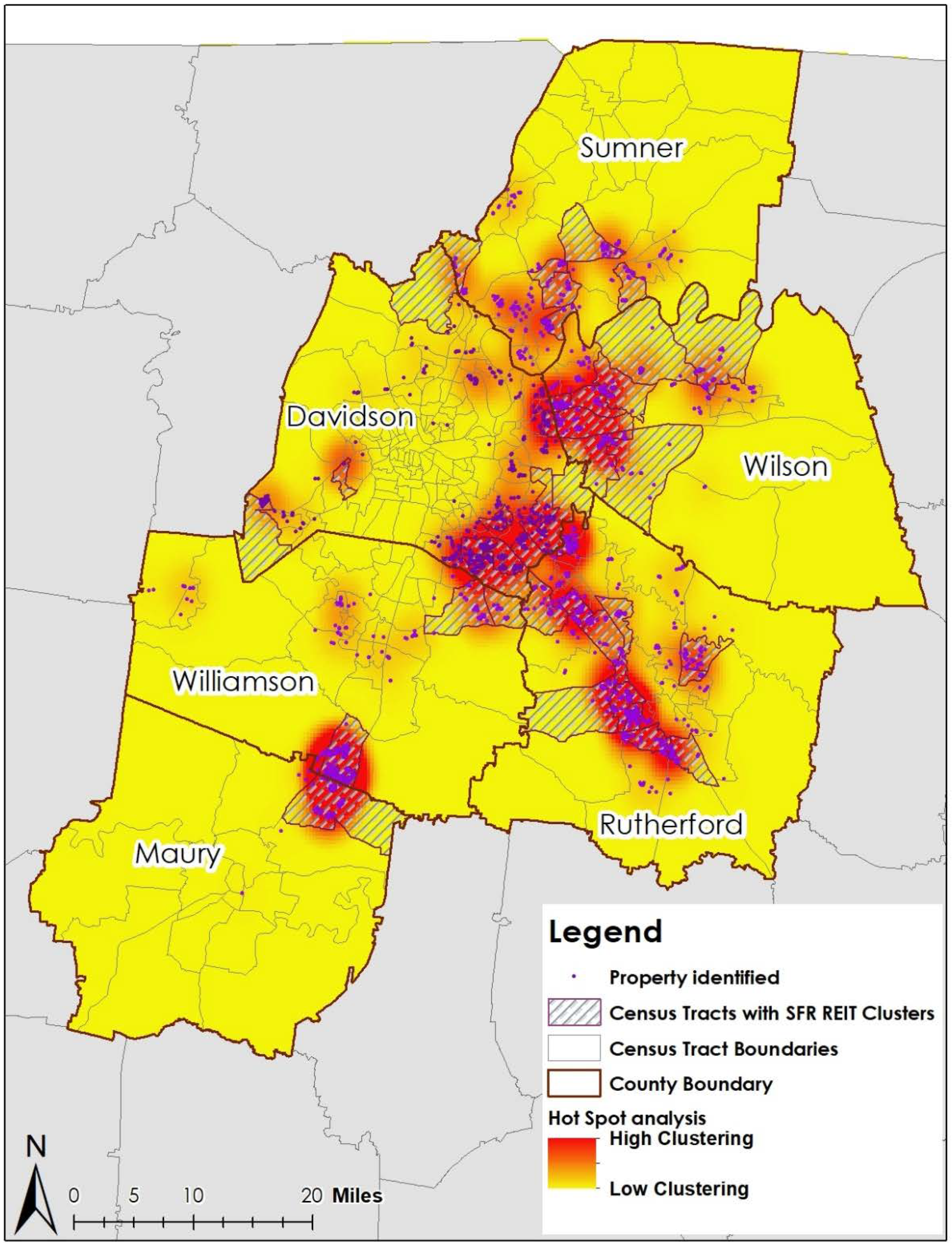

Nashville Overview

3. Results and Interpretation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, S.H.; Erickson, J.; Wang, K. Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-019515534. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, G.; Fischer, F. The Role of REITs in REIT Portfolios. J. Real Estate Portf. Manag. 2009, 15, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, D.; Kohli, R.; Schafran, A. The Emerging Economic Geography of Single-Family Rental Securitization; Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amherst Capital Management. U.S. Single Family Rental: Institutional Activity in 2016/2017; Amherst Capital Management: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.; Molloy, R.; Zarutskie, R. Large-Scale Buy-to-Rent Investors in the Single-Family Housing Market: The Emergence of a New Asset Class. Real Estate Econ. 2017, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M. The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aalbers, M.B. The Variegated Financialization of Housing. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D. Unwilling Subjects of Financialization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D. Constructing a New Asset Class: Property-led Financial Accumulation After the Crisis. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 94, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. The Secondary Circuit of Capital Reconsidered: Globalization and the U.S. Real Estate Sector. Am. J. Sociol. 2006, 112, 231–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, R. Capitalizing on the State: The Political Economy of Real Estate Investment Trusts and the ‘Resolution’ of the Crisis. Geoforum 2018, 90, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandri, G.; Jampscka, M. Who Loses and Who Wins in a Housing Crisis?: Lessons from Spain and Greece for a Nuanced Understanding of Dispossession. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijburg, G.; Aalbers, M.B.; Heeg, S. The Financialisation of Rental Housing 2.0; Releasing Housing into the Privatised Mainstream of Capital Accumulation. Antipode 2018, 50, 1098–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glink, I. 10 Worst Cities for Foreclosures in 2010. CBS News Moneywatch. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/10-worst-cities-for-foreclosures-in-2010/ (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Abood, M. Wall Street Landlords Turn America Dream into a Nightmare; ACCE Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and Cleveland and the Federal Reserve Board. REO & Vacant Properties: Strategies for Neighborhood Stabilization. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/one-time-pubs/reo-vacant-properties-strategies-for-neighborhood-stabilization.aspx (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Reid, C.K. Shuttered Subdivisions: REOs and the Challenges of Neighborhood Stabilization in Suburban Cities. In REO & Vacant Properties: Strategies for Neighborhood Stabilization. A Joint Publication of the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and Cleveland and the Federal Reserve Board; Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 23–32. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/one-time-pubs/reo-vacant-properties-strategies-for-neighborhood-stabilization.aspx (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Immergluck, D. Holding or folding? Foreclosed Property Durations and Sales During the Mortgage Crisis. In REO & Vacant Properties: Strategies for Neighborhood Stabilization. A Joint Publication of the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and Cleveland and the Federal Reserve Board; Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 33–46. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/one-time-pubs/reo-vacant-properties-strategies-for-neighborhood-stabilization.aspx (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Donner, H. Foreclosures, Returns, and Buyer Intentions. J. Real Estate Res. 2017, 39, 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, K.; Moore, T.; Soaita, A.; Crawford, J. ‘Generation Rent’ and the Fallacy of Choice. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, R.; Kadi, J. The revival of private landlords in Britain’s Post-Homeownership Society. New Political Econ. 2017, 23, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strochak, S. Five Things That Might Surprise You about the Fastest-Growing Segment of the Housing Market. Urban Institute Urban Wire. 2017. Available online: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/five-things-might-surprise-you-about-fastest-growing-segment-housing-market (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Wiggin, T. Welcome to Wall Street’s Housing Market. Available online: https://www.inman.com/2017/06/09/welcome-to-wall-streets-housing-market/ (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Edelman, S.; Gordon, J.; Sanchez, D. When Wall Street Buys Main Street: The Implications of Single-Family Rental Bonds for Tenants and Housing Markets; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, D. The Rise of the Corporate Landlord: The Institutionalization of the Single-Family Rental Market and Potential Impacts on Renters; The Right to the City Alliance: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amherst Capital Management. U.S. Single Family Rentals: An Emerging Institutional Asset Class; Amherst Capital Management: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis: Nasville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin, Tennessee; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/NashvilleTN-comp-17.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- Kotler, M. Neighborhood Government: The Local Foundations of Political Life; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0739109915. [Google Scholar]

- The Capital Forum. Single-family Rental Industry: Companies Lean on Tenant Chargebacks to Effectively Cut Operating Expenses. Available online: https://thecapitolforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SFR-Industry-2018.02.21.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- The Capital Forum. Single-Family Rental Industry: Company Keeps Tenant Security Deposits, Pad Move-Out Statements, Turn Former Tenants’ Accounts over to Debt Collectors. Available online: http://createsend.com/t/j-C6FE0B7A08F706392540EF23F30FEDED (accessed on 3 March 2018).

| Company | Number of Homes | Investor | Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invitation Homes * | 48,038 | Blackstone | $8.9 billion |

| American Homes 4 Rent | 48,000 | Alaska Permanent Fund | $9.6 billion |

| Colony Starwood | 30,844 | Colony Capital; Starwood Capital | $5.9 billion |

| Progress Residential | 17,333 | Goldman Sachs | $3.0 billion |

| Tricon | 17,249 | Tricon Capital | $1.4 billion |

| County | SFR REIT Properties | Total Single Family Detached Units | Percent REIT-Owned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Davidson | 825 | 176,579 | 0.47% |

| Rutherford | 733 | 80,387 | 0.91% |

| Williamson | 512 | 61,511 | 0.83% |

| Wilson | 454 | 38,818 | 1.17% |

| Sumner | 285 | 53,174 | 0.54% |

| Maury | 161 | 26,921 | 0.60% |

| TOTAL | 2970 | 437,390 | 0.68% |

| Metro-Area (N = 325) | Non-REIT Tracts (N = 156) | REIT Tracts (N = 169) | REIT Clusters (N = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Population White | 74 | 72 | 76 | 77 |

| Percent of Population African American | 18 | 21 | 16 | 15 |

| Percent of Population Hispanic/Latino | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Median Age | 37.02 | 36.71 | 37.3 | 36.52 |

| Percent Less than High School | 12 | 13 | 10 | 7 |

| Percent Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 32 | 31 | 32 | 35 |

| Average Household Size | 2.59 | 2.47 | 2.7 | 2.82 |

| Median Household Income | $60,579 | $56,277 | $64,499 | $72,507 |

| Percent Below Poverty | 15 | 19 | 11 | 7 |

| Percent Unemployed | 7 | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| Median Year Built | 1982 | 1975 | 1988 | 1997 |

| Median Housing Value | $209,770 | $221,938 | $198,826 | $208,829 |

| Median Rent | $987 | $929 | $1039 | $1150 |

| Percent of Owner Occupied Units Paying 30% or more of Income on Housing | 24 | 25 | 23 | 22 |

| Percent of Renter Occupied Units Paying 30% or more of Income on Housing | 43 | 44 | 42 | 37 |

| Percent of Single Family Units Owner Occupied | 60 | 52 | 67 | 75 |

| Percent of Single Family Units Renter Occupied | 12 | 14 | 12 | 11 |

| Percent of Single Family Units Vacant | 28 | 34 | 21 | 14 |

| Percent of Single Family Units REITs | 0.46 | 0 | 0.87 | 2.35 |

| Non-REIT Tracts (N = 156) | REIT Tracts (N = 169) | α < 0.05 | Unclustered REITs (N = 124) | REIT Clusters (N = 45) | α < 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Population White | 72 | 76 | 76 | 77 | ||

| Percent of Population African American | 21 | 16 | 17 | 15 | ||

| Percent of Population Hispanic/Latino | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | * | |

| Median Age | 36.71 | 37.3 | 37.59 | 36.52 | ||

| Percent Less than High School | 13 | 10 | * | 11 | 7 | * |

| Percent Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 31 | 32 | 31 | 35 | ||

| Average Household Size | 2.47 | 2.7 | * | 2.65 | 2.82 | * |

| Median Household Income | $56,277 | $64,499 | * | $61,592 | $72,507 | * |

| Percent Below Poverty | 19 | 11 | * | 12 | 7 | * |

| Percent Unemployed | 8 | 6 | * | 6 | 5 | * |

| Median Year Built | 1975 | 1988 | * | 1984 | 1997 | * |

| Median Housing Value | $221,938 | $198,826 | $195,196 | $208,829 | ||

| Median Rent | $929 | $1039 | * | $999 | $1150 | * |

| Percent of Owner Occupied Units Paying 30% or more of Income on Housing | 25 | 23 | * | 24 | 22 | |

| Percent of Renter Occupied Units Paying 30% or more of Income on Housing, | 44 | 42 | 44 | 37 | * | |

| Percent of Single Family Units Owner Occupied | 52 | 67 | * | 64 | 75 | * |

| Percent of Single Family Units Renter Occupied | 14 | 12 | * | 12 | 11 | |

| Percent of Single Family Units Vacant | 34 | 21 | * | 24 | 14 | * |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chilton, K.; Silverman, R.M.; Chaudhry, R.; Wang, C. The Impact of Single-Family Rental REITs on Regional Housing Markets: A Case Study of Nashville, TN. Societies 2018, 8, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040093

Chilton K, Silverman RM, Chaudhry R, Wang C. The Impact of Single-Family Rental REITs on Regional Housing Markets: A Case Study of Nashville, TN. Societies. 2018; 8(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleChilton, Ken, Robert Mark Silverman, Rabia Chaudhry, and Chihaungji Wang. 2018. "The Impact of Single-Family Rental REITs on Regional Housing Markets: A Case Study of Nashville, TN" Societies 8, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040093

APA StyleChilton, K., Silverman, R. M., Chaudhry, R., & Wang, C. (2018). The Impact of Single-Family Rental REITs on Regional Housing Markets: A Case Study of Nashville, TN. Societies, 8(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040093