1. Introduction

The effects of television and its news programs on shaping people’s beliefs, ideas and values has long been the subject of study ever since this medium was invented. Gerbner’s cultivation theory argues that television has the power to influence people’s vision of the world around them. Social constructionists Schutz [

1] and Berger and Luckmann [

2] argue that different media sources affect people’s view of the realities around them. One of the most influential sources today is the media which adds to the person’s socially constructed view of reality. Walter Lippmann [

3] issued the agenda-setting theory, in which he believed that the news media could set the agenda for the public’s attention to the issues surrounding them. An important issue that exists in each society is crime. Recent surveys indicate that despite actual crime rates having decreased in the U.S., people’s fear of crime has in fact increased. This article will discuss the media and its coverage of crime topics, especially in news programs, as one of the key causes of such existing contradictions within U.S. society.

The article will expand on the issue in five primary sections. In the first section we will provide a general overview of the development of the media in regards to the cultivation theory perspective. In the second section we will define how the social construction of reality takes place. The third section will argue how the social construction reality supports and moves in line with the cultivation theory perspective. In the fourth section, the article will take a look at some statistics of crime and fear of crime and reflect on the contradictions that exist between the two sets of statistics. In the final section, the article will explain the public’s demand on the media and how their set agendas are interrelated between the cultivation theory and the agenda-setting theory effects. This will be discussed using the discourse analysis methodology and by taking a look at some primary source surveys like the Gallup poll, Bureau of Social Statistics and the Pew Research Center.

2. Cultivation Theory Perspective

Based on the Cultivation theory (Gerbner and Gross, [

4]; Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, and Signorielli, [

5]), the media shapes people’s reality and their views on the world around them. According to the cultivation theory, people with high levels of exposure to television tend to receive more messages from the broadcasts on television and therefore, gradually adapt their views and beliefs on the issues around them based on these constant messages. For example, a person who constantly watches crime news may think that the sample society portrayed in that crime news program is full of crime as this is the only information that viewer is receiving from that certain location. This location may or may not be the same location where the viewer him/herself is living. Thus, this person will view the world around them as a more violent world, full of crime as compared to a person who spends more of their time watching wildlife programs. The content that we are most exposed to shapes our view about the world around us.

In their article, Gerbner and Gross [

4] focused on the effects of television programming on the attitudes and behaviors of the U.S. public, especially as to violent programming. Through extensive research and quantitative analysis, foremost scholars in this field have since found some correlation between the amount of television exposure and forming conceptions of social reality for many topics, such as violence (Gerbner, [

6]; Signoreilli and Morgan [

7]; Shanahan and Morgan, [

8]; Gerbner, [

9]). The way people make generalizations in their minds is by relying on and referring to the already available examples that exist in their memory (Tversky and Kahneman, [

10]). The frequency of exposure to crime news causes the viewers mind to make a quicker reference to the available example or instance already given to him/her by the media. Perse [

11] argued that local broadcast news should have a stronger cultivation effect than other program types for several reasons: Its depiction of violence does not jibe with reality, crime and violence dominate the news, local news is dramatic, and local news is heavily watched and perceived as realistic, all of which bear directly on the explanatory mechanisms underlying cultivation theory.

Despite changes in the trend of news consumption, following a fall in the use of television as a source of news, television is still the most common and widely used source of news for the U.S. public. The Modern News Consumer report by Mitchell, Gottfried, Barthel and Shearer [

12] argues that 57% of U.S. adults still get their news from television. The trend on using television as a news source has decreased as compared to before but it is still among the most common resources for news gathering. There seems to be a close competition facing the future of television and digital news sources and the trend in news consumption since the use of digital news sources has had a dramatic rise. However, as both television and digital news sources usually gather their news from the same wires such as Associated Press, Agence France-Presse and Reuters, a change in news sources may not change the fear of crime statistics as such. Since this is not confirmed, the author believes that this field is still open to research and investigation.

3. Social Constructive Reality

Social constructionists Schutz [

1] and Berger and Luckmann [

2] believe people gain their social knowledge of reality through four sources: Personal experiences, significant others (such as family members and friends), other social groups and institutions (such as schools and churches) and finally, the media. The knowledge gained from these sources constructs a reality of the things around us. Accordingly, three types of realities are then shaped throughout our lives: Experienced reality, symbolic reality, and socially constructed reality.

Experienced reality is the reality we gain from our everyday interaction with the world around us. An example of this is a person who is the victim of a social crime, like kidnapping or torture, who will experience what it means to go through such a reality and will have a knowledge built on the issue according to his/her experience.

Symbolic reality is the reality or knowledge which is gained from three other sources namely peers, institutions and the media. This consists of facts that you have not witnessed or personally collected but believe to be true and to have occurred. An example of symbolic reality can be the fact that you believe the earth orbits the sun; you have not seen that personally but you will believe in it based on the information which is given to you via the three sources, in this case it can be a friend, school or a television program. The same applies to acts of crime. Even if the number of kidnappings you have seen personally with your own eye may be none, you still believe in it because you know that it existed through your information or symbolic reality which was given to you by the media or your peers.

Socially constructed reality is the total reality and knowledge gained from the mix of both our experienced reality and our symbolic reality together. The sum of knowledge gained from all of these sources allows us to feel as if we have been through all that we have experienced and heard because we have the power to relate things together and to construct our own reality of the world around us based on it. This is why we all perceive the world differently and it is also why people who have faced the same experience and sources of reality happen to have the same view towards different things.

As we can see, based on the social constructivist reality point of view, most of what the world that we perceive we live in and what our views are based on, consists of the experiences we all go through and the symbolic reality we gain from the outside. Since the life of all human beings is limited and we cannot go through every experience in the world all by ourselves, a vast majority of our reality is gained through this socially constructed process of others. With the advance of technology and the vast communication abilities, we tend to be more exposed to different sources of the media, such as television and the internet, and naturally receive more of our realities via this source. As a result, most of us tend to agree on the socially constructed realities we gain from the three sources apart from our own personal experience as it would be too risky to gather the knowledge all by ourselves.

The role of the media in the social construction process as explained by Surette [

13] has been represented in four stages. In Stage 1, we have the conditions, events and properties which set the boundaries as to the path in which the following stages must move along. This stage consists of the actual physical world we live in. In this stage, events such as crimes or terrorist acts occur and are noted by individuals and organizations. The built constructions of reality must now move within the realm of this constructed physical reality. A person may seek to form a happy family, however, the social construction of the family may not last long if they are constantly having fights and arguments within the family.

In the second Stage, the competing constructions emerge with their different views of what the physical world or reality may be like. Here we have a set of descriptions which are frequently in conflict and compete with the initial perception of reality that has been shaped. This could mean that while you are struggling to hold your family together among the conflicts you are facing, you hear about statistics on how prevailing divorce and family problems have become.

In the third stage, where the media steps in, the completion will now be drawn to one side. This is the side of the media which has functioned like a filter in order to draw attention to its favored position. The media has the power of the mainstream and constructs the reality based on the topics and events it most likes to cover. What is left out and considered as unimportant is whatever is less covered by the mainstream media.

Stage four is where this now dominant socially constructed reality is chosen to direct public policy because it has become the prevailing reality. The policy makers now decide and think based on these socially constructed realities since they are considered the most important constructions of society.

For crime and justice, this socially constructed reality will define the conditions, trends, and factors accepted as causes of crime, the behaviors that are seen as criminal, and the criminal justice policies accepted as reasonable and likely to be successful. Media are centrally situated in the distribution of knowledge, and what we see as crime and justice is largely defined, described, and delimited by media content.

4. Social Constructive Reality Explains Cultivation Theory

The most comprehensive effort to integrate the empirical study of symbolic contents and the construction of subjective reality is that of Gerbner and his associates. The Cultural Indicators Project compares the statistical facts of objective reality to the facts of television reality and investigates audience perceptions in terms of correspondence to one of the two realities. According to their theoretical exposition, Gerbner and his colleagues were interested in the whole process of cultivation. Accordingly, they investigated both the dominant modes of symbolic representations of objective reality in media entertainment programs and the impact of this symbolic environment on the individual’s perception of social reality (Hanna Adoni and Sherrili Mane, [

14]). Shrum and O’Guinn [

15] said that the construction of social reality is simply cultivation itself. As McQuail [

16] put it, George Gerbner’s cultivation theory of communication is an approach to the study of how mass media affect the individual’s construction of social reality. Ogles [

17] believes that social reality is generally defined as a total of internalized, learned expectations derived from our past experiences and information, such as that obtained from media exposure. As Gerbner [

18] believes, heavy viewers are likely to see the world according to the social reality constructed by television as compared to light viewers.

Therefore, we can see how the social construction of reality theory of Schutz [

1], Berger and Luckmann [

2] fits within the framework of Gerbners cultivation theory. In the social construction of reality process, the individual builds their world experience according to the set of experiences across their life and mostly from the three other sources of knowledge: Peers, institutions and the media. The media as a mainstream plays an important role in shaping the knowledge and ideas of the peers which surround a person and also the people who run the institutions.

As generations go by, we can see a whole new society who gains knowledge and experience from the mainstream as it is the most convenient source to access. In a media dominant society, it is natural to expect that individuals will be affected by the power of the media. In this case, if we limit the media to the news programs broadcasted on television, and if these news programs spend most of their time talking about crime and violence this may change your mind about the safety of the society you are living in, before and after you have heard that news piece. This shaping of views and constructed reality is where the socially constructed reality via the media plays a role in an individual’s life. The effects of this media power will then be the effect mentioned in cultivation theory. This is how the two theories fit into each other when it comes to the role of the media in shaping the audience’s views of the outside world or society. Once the social construction of crime as a reality is set, the viewer will label that topic (crime) as an important issue of reality in his/her society and will set that agenda as knowing more about that issue. In the following sections the article will elaborate further on this relationship.

5. Where Do the Crime Statistics and the Public’s Fear of Crime Stand?

A 1997 study published by the Center for Media and Public Affairs (CMPA) [

19] found that since 1993, coverage of murders on network evening news shows rose over 700% and overall crime news tripled. Between 1993 and 1996, crime was the most heavily covered topic on network evening news, with 7448 stories, or one out of every seven news stories on all topics. The amount of crime news tripled from the early 1990s, although violent crime rates declined during the same period (CMPA 1997a). According to CMPA, 24% of all stories on the leading syndicated tabloid television news programs dealt with crime.

As measured by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism’s annual survey (The Year in the News: All News by Topic, [

20]), crime news took up about six percent of the “newshole” in a sampling of publications, radio and television broadcasts, and online outlets in 2011. This rate change moved two percent from 2010, where it stood at four percent, down slightly from about six percent in 2009. In 2008, the crime coverage rate in the news was approximately seven percent. In the year 2007, the annual crime coverage stood at eight percent. Access to the statistics for the years in-between could not be found. In all of these years, the topic of crime was one of the most covered news topics on U.S. media as a whole.

A Gallup survey by McCarthy [

21] found a fairly dramatic decreasing trend in violent crime rates in the U.S. In a natural situation, it could be expected that a drop from an 80 percent crime rate in 1993 to a 20% crime rate in 2014 would be felt among members of the social community. That is, safety within the community will naturally be promoted and people will tend to have less fear of crime. However, the same study reported that the U.S. people’s understanding of crime statistics was in fact the opposite. Most tended to think there was an increase in crime rates as compared to previous years. Gramlich’s [

22] study also supports the fact that the public’s perceptions of crime rates are at odds with actual crime statistics. People’s belief in crime is not comparable as to the actual fall in crime rates. The question that is raised here is why is that so? How do people know whether the crime rates have increased or decreased? Where are their sources of knowledge? Or should we say: How have they constructed their social reality in a way that tells them there is more crime around them than there actually is?

According to the social constructivist, and based on the individual’s experienced reality, an individual will have a perception about the world around him/her by the experiences they have in life. Could this mean that the 68% who believed there was a rise in crime in 2006 were all the subject of violence themselves and therefore made such a conclusion about their surrounding society?

Statistics prove contrary. In fact, in a poll carried out by the National Center for State Courts, people were asked if they or a family member had been a victim of a violent crime involving force or a weapon (The NCSC Sentencing Attitudes Survey: A Report on the Findings, [

23]). Only 9% said “yes”. This means that 91% not only had no experienced reality of the issue but had not even had any symbolic reality through the two sources of peers and schools. According to the Gallup poll carried out in the same year, a rise in the sense of crime existence was seen among the participants. This means that more people thought that crime had increased according to the previous year in their area. But where did they get this feeling from when in fact 91% of them had not been subject to crime or had a close family member who had been the subject of crime? This leaves the media as the final source of knowledge or experience for those who thought they had a fear of crime due to the rise of violence in their society. Gordon and Heath [

24] and Jaehnig, Weaver, and Fico [

25] found that people who read newspapers and watched local news that focused on crime news also exhibited higher levels of fear of crime than those who did not (Smith, [

26]). Research has also found that the public believes that crime levels are the same or worse than what is presented in the media (Parisi et al., [

11]). What the public ‘knows’ about crime and crime policy is thought to be heavily influenced by the mass media (Roberts and Doob, [

27]; Roberts and Stalans, [

28]). Altheide [

29] has done extensive research scrutinizing the discourse of fear, crime and terrorism within the country’s mass media. After content and discourse analysis he found that the public’s perceptions about crime and war were very much informed by propaganda and news reports about relevant acts. This gives way to prove how the cultivation theory and the socially constructed reality paves the way for individuals’ view of their outside world.

But what about the role of the viewers? Do they stay idle within this mind-shaping process of the media? Do they give feedback? If so, how does their feedback count and do they help to strengthen the process of the media? This next section will focus on how viewers affect the media’s coverage of crime.

6. Crime, the Public’s Popular Topic and the Agenda-Setting, Cultivation Theory Cycle

The media stands on one side of the social construction and cultivation of crime news stories. But should only the media be blamed for providing individuals with the information they think they need? Individuals also want to gain knowledge about things that directly or potentially affect their lives. Several studies have found that local broadcast news is both popular and trusted in the minds of viewers (Comstock, Chaffee, Katzman, McCombs, and Roberts, [

30]). A survey carried out by Rosenstiel, Mitchell, Purcell and Rainie [

31] asked a nationally-representative sample of adults whether they ever got news and information on 16 different local topics. Its top results were: weather (89% of people get it), breaking news (80%); local politics (67%) and crime (66%). The least popular on our list of topics was zoning and development information (30%), local social services (35%), job openings (39%) and local government activities (42%). It is clear from the survey that not all local topics are equally popular. Crime has been one of those topics that captures the public’s attention and popularity. This result motivates the media to give more coverage to crime-related topics and news.

The same study by Rosenstiel, Mitchell, Purcell and Rainie [

31] has done a comparison between those viewers who are more enthusiastic about their local news and constantly follow it and those who are less enthusiastic and regularly follow it. The result was that in both cases, crime had been one of the most popular, or more likely to be viewed topics by locals. Crime topics were favored by 71% of local news enthusiasts and 57% of non-enthusiasts of local news still searched for crime as one of their top priorities for news information. This shows that the public demanded crime news as one of their top necessities no matter to what extent they had been attached to their regular television watching programs.

When people rate crime as one of their most popular topics, they set an agenda for themselves and also for the media as to which news to cover most. The agenda-setting theory claims that the media plays an influential part in how issues gain public attention. ‘Agenda-setting’ studies found that individuals’ concern with various issues was positively related to television news coverage of these issues, at least among uncommitted voters (McCombs and Shaw, [

32]). For example, Iyengar et al. [

33] found that television news coverage of specific issues such as unemployment or education significantly influenced viewers’ evaluations of presidential performance. Moreover, the more prominent the story was in the broadcast, the more influence it appeared to have. For the politically uninformed, media presentations were much more influential in shaping their attitudes. Among the more politically knowledgeable, media accounts triggered critical deliberations of the information. The authors concluded that viewers do in fact use television to understand their social reality, especially to determine which national issues to consider as most serious (Callanan, [

34]). Gross and Aday’s [

35] research argued that watching local news had large, significant effects on agenda-setting. As compared with those who never watched local television news, heavy viewers were significantly more likely to mention crime as an important problem.

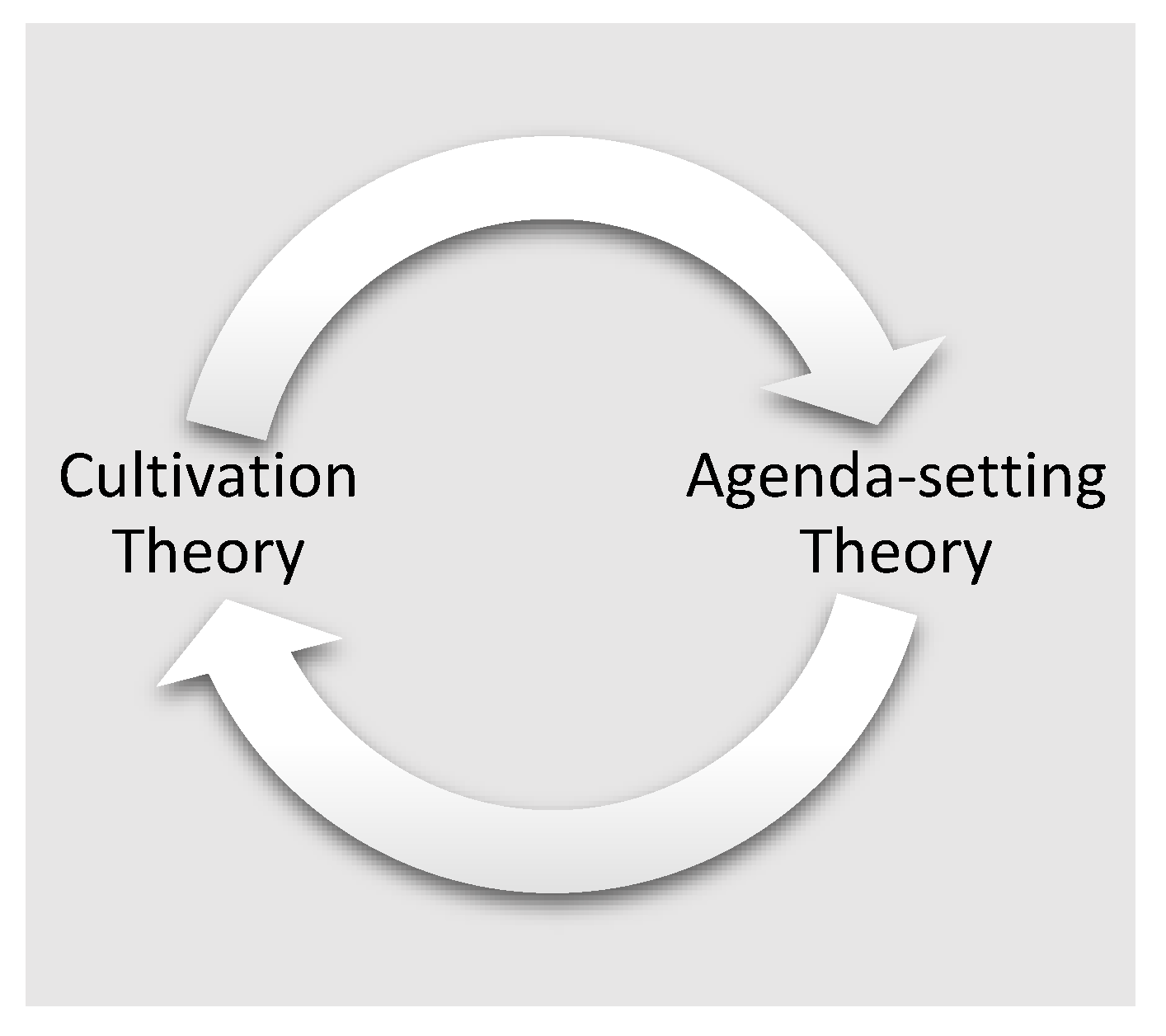

With a look at many studies in the field of agenda-setting and cultivation theory we can say that the two theories support each other and are related to each other in a repetitive cycle form. Through cultivation, the audience is overexposed to a certain type of topic via the media, in this case crime, magnifying the topic in the audience’s mind. The topic will be now considered as a top agenda for the viewer and based on the agenda-setting theory he/she is more likely to pursue the issue because of the amount of importance given to it. In other words, the media has managed to set an agenda for the viewer and by setting an agenda they can simultaneously set the viewers expectations of television coverage (in this case crime news).

In its evolution through five stages, agenda-setting theory has incorporated a variety of other established communication concepts such as status conferral, stereotyping, image building and gatekeeping (McCombs, [

36]). All media effects theories focus on some form of change in audience beliefs, perceptions, knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, emotional states, or values. Agenda-setting is often linked to cultivation effects, as both explain an audience’s processing of messages leading to accumulative effects across time. Jeffres, Neuendorf, Bracken and Atkin [

37] integrated agenda-setting and cultivation theories together through the third-person perception theory. This article contributes to similar existing literature by discussing the link between the theories through emphasis on the accumulative effect of the two theories and how each theory strengthens the effect of the other by magnifying the topics in the mind of its audience as it processes in the given cyclical model.

Agenda-setting and cultivation can, therefore, be seen as part and parcel of the larger discussion about the media’s relative power vis-à-vis audiences, that has dominated mass communication research for at least 60 years. Both theories have spurred numerous studies demonstrating, refining, and in some cases challenging the original work. Both at their core argue that television does influence the way audiences think about the world in which they live. Therefore, both theories are linked together in a cycle that is generated by the media influence and the public’s top priorities. What can be clearly examined today is that the media sets agendas for the public through cultivation of its topics, and the public’s agenda sets the priority for news coverage for the media. This accumulative cyclical relationship is illustrated in the model in

Figure 1:

Further research is needed to determine which element starts first in the cycle. Could it have been the fact that the audience in general were more interested in crime news in the first place and so their constant demands of crime news motivated the media to give the viewers more of what they wanted? Was it the media’s will to cover the crime news that generated the audience to cultivation and more demand of this type of coverage? Whichever the case, today the public do believe that crime is one of the important topics that should be covered and despite the decrease in crime rates, the public fear more than before about the possibility of crime occurrence around them.

7. Conclusions

The gradual rise in the public’s fear of crime, despite the fall in actual crime rates, has some roots in the cultivating effect of the media. The media has socially constructed the reality that the occurrence of crime is quite common and on the rise in the U.S. public’s mind and psyche. This socially constructed reality of the existence of crime urges the public to prioritize crime as one of the most important issues concerning their community. Through agenda-setting, the public will then set crime as a key issue to follow in the media. This agenda-setting itself which in turn might have been primarily triggered by the media will then create the public’s collective demand from the media to cover stories which they think have the utmost importance. One of which, is crime. This cycle of media crime exposure and public demand of crime, illustrates the relationship between cultivation theory and the agenda-setting theory. The model presented in this article suggests that the two theories reinforce each other in a constant repetitive cycle, creating an accumulative agenda effect which magnifies the agenda more and more as the cycle continues.

As a final overview, this article has discussed two important effects of cultivation theory on the U.S. public’s belief of reality of crime. First, it makes them think that crime is increasing and exists in the community around them, and second, it has caused the public’s fear of crime to increase due to this incorrect belief. Both of these effects are the result of the socially constructed reality of crime on the U.S. public which has lead them to value crime news as one of their top agendas to follow in the media. The valuing of crime urges the media to produce and expose people to more crime topics and to magnify the issue through the accumulative agenda effect.