1. Introduction

The programs aimed at improving the quality of life and the health of the older adult population (people over 65 years of age, according to the definition of the World Health Organization) are a response to the increasing ageing process of the general population, as a direct consequence of the increase in life expectancy throughout the world, which is producing significant changes in the demographic pyramid [

1]. This increase in life expectancy is an important indicator of the cultural development that reflects the improvement and evolution of the social welfare policies of states, but at the same time it represents a challenge due to the high cost related to the economic, social and health-related attention that the older adult population requires.

For this reason, the concept of “healthy life expectancy” has been developed, which basically consists in including a new dimension, “the adding of the quality of life to the number of years of life” [

2] (p. 12). This concept of healthy life expectancy is based on two dimensions: chronic morbidity on one hand and self-perceived health on the other. Due to this conditionality, an increase in life expectancy, and therefore longer survival, can occur at the same time as an increase in co-morbidity, in which case, healthy life expectancy will decrease. In the Spanish context, this means that after 65 years of age, women have a Life Expectancy (LE) of 23.4 years, while men have a LE of 19.2 years. Today, 38% of the women’s LE years are enjoyed without suffering limitations of activity, which means that women have a healthy life expectancy (HALE) of nine years, while the HALE of men is 51% of their EV, that is, 9.7 years. One can see that, while women have a higher LE than men (23.4 compared to 19.2), their HALE is lower both when measured in total years (nine years versus 9.7) and when measured in percentage of life without limitations (38.5% vs. 50.5%). In short, the goal is to ensure that as the ageing process occurs, the percentage of time lived in good health increases.

In line with this cultural context, responses are being offered from numerous national and international institutions, such as the European Policy Center for Social Welfare and Research, Eurolink Age in the United Kingdom, the International Federation of Associations of the Elderly, and the World Health Organization (WHO). These institutions promote socio-cultural programs and cognitive activities, in addition to developing scientific research, which offers new perspectives, such as multi-component training programs, multi-sectoral work to prevent falls, and the maintenance of physical and mental abilities and qualities [

3,

4,

5]. Among the novelties of the proposed programs are training circuits integrated by functional movements (Functional Movement Circle) [

6], the use of Core Instability Strength Training [

7,

8], and Slackline training [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Judo training has also been used in combination with pharmacological prescriptions for prevention and treatment in populations with diseases such as osteoporosis, in order to achieve an increase in bone mineral density. These research projects have produced very promising results [

11,

12].

This paper reports on the Judo Utilitario Adaptado project (Adapted Utilitarian Judo, hereafter, JUA). The JUA project was born in Spain in 2015, as a result of the educational and research proposal of Judo masters Luis Toronjo Hornillo and Óscar del Castillo Andrés, members of the Physical Education, Health and Sports Research Group of the University of Seville (Spain). To start off the JUA project, in June of this year, a research contract was signed between the aforementioned research group and CerOOne Technology, a company that economically supported the study, design, and implementation of the JUA program. This is a pioneering innovation occurring worldwide but that at the same time maintains its roots and connections to tradition. We believe that the use of Kodokan Judo (intended as the set of Judo techniques taught by the judo master Kano in his dojo, called Kodokan) is an initiative that offers a response to specific demands of the older adult population, which has its own needs and characteristics. For its development, the program has been based on the methodological proposal of Maza [

13], focusing attention on aspects oriented to the design of physical activity and social integration, through the use of sports activities that are modified according to the characteristics of the target population, through the introduction of significant and non-significant adaptations; in this case, the adaptation of Judo, a traditional Japanese martial art, also known worldwide as a competitive Olympic sport.

In JUA, participants work collaboratively, cooperatively, and with assistance. Assimilation activities are proposed [

14], which are linked to the safety elements of the methodology of teaching Judo, and which are necessary, as in any physical sports activity, for the safety of the older adult, to avoid any situations that could entail risk or potential harm. This design allows for automating technical gestures effectively, transforming the practice of Judo into a useful and versatile tool for the maintenance and functional improvement of the targeted older population through a traditional Martial Art which is oriented toward personal development and development through psycho-physical training [

15,

16].

We also support that the practice of Judo in this adapted way also goes beyond the aspects of maintenance and physical improvement that it can provide to its practitioners. Practice also forms a link to this physical culture’s origin and philosophy through establishing connections with the martial arts that gave rise to Judo. Thus, the training of techniques that can serve to respond to an aggression also influences its practitioners and becomes a means toward personal growth through the formation of an attitude of overcoming the inherent difficulties of daily life.

1.1. Judo vs. Adapted Utilitarian Judo

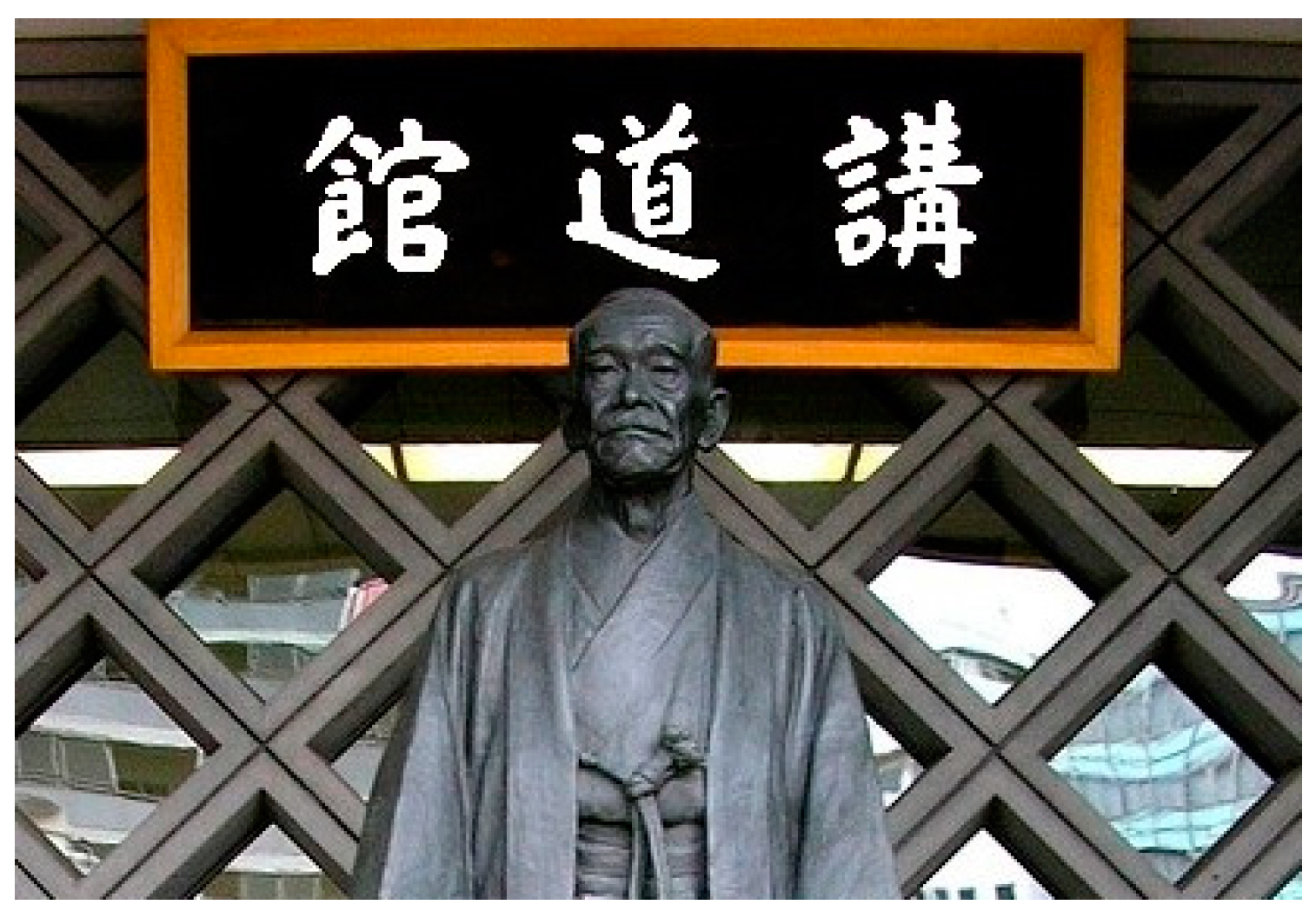

“Judo—more than a sport” is a phrase that is included as part of the logo that identifies the European Judo Union. This is not the motto of an advertising campaign or an image strategy but responds to the cultural legacy of Judo, created in 1882 by Jigoro Kano (

Figure 1). Originally, Judo was not conceived as a sport but as an educational instrument with a high content in values, which would serve as a tool for the integral education of people, with which to contribute to the improvement and benefit of society: “For the true benefit of oneself, one must also take into consideration the benefit of society. The greatest prosperity of oneself can be achieved through service to humanity” [

17] (p. 8). With this double perspective, Jigoro Kano distinguished between “kyogi” or judo in a limited sense, practiced with the sole objective of physical improvement and a better combat technique, and “kogi”, which refers to Judo in a broad sense, focused on the integral education of people, and, through this, the improvement of society.

This perspective, which forms part of Kano’s legacy, carries a clear humanistic vocation, which corresponds to the Oriental currents of cultural development in terms of what Judo must contribute to and mean for today’s society. Official Judo institutions (Inter-national Federations, National Federations, and Regional or Territorial Federations) still share these values. The interest of these institutions in recovering and maintaining the values present from the beginning in Kodokan Judo is evident, for example, in the pre-amble to the statutes of the International Judo Federation [

18].

In this sense, JUA has the participation of the European Judo Union (EJU) and the cooperation of the Andalusian Federation of Judo and Associated Sports (FANJYDA), both of which have established a collaboration agreement with the University of Seville (US) and have contributed to the financing of the program, to develop the JUA program and its contents, making the necessary adaptations for the older adult population while trying not to lose the foundations and the possible values associated with the practice of Judo. Without forgetting Judo as a sport (whether or not it is focused on competition), we are trying to return to a practice in accordance with the original ideals of Judo, allowing the coexistence of different orientations and valuing other variants such as Judo Education, Judo Health, and Judo for Society, all of them linked to the potential original values and closely interrelated.

Jigoro Kano made a distinction of the objectives to achieve through the practice of Judo between “kyogi” or Judo in a limited sense, practiced with the sole objectives of physical improvement and a better combat technique, and “kogi”, which corresponds to Judo in a wide sense, focused on the integral education of people and thus on improving society [

17]. Since its inception, Judo, through its 136 years of existence, has shown itself to be an activity that has managed to adapt to different cultures to become a universal cultural phenomenon that, starting from Japan, is present in 204 countries around the world. Its greatest asset is undoubtedly its programmatic proposal that, with a holistic vision of people, transcends the individual sphere to the social dimension through the principles that Jigoro Kano enunciated as fundamental in the practice of Judo, of which two stand out: “Seyryoku Zenyo”, the principle of maximum efficiency in the use of physical and mental energy, and “Jita Kyoei”, the principle of mutual benefit and prosperity (

Figure 2).

These principles are not intended to end when the training session ends, nor are they valid only in the dojo, but they must be present in all facets of a practitioner’s life. The first is a clear example of the importance of always applying knowledge rationally, to achieve a specific goal or objective, while the second principle shows the true dimension of Social Judo, through the necessary relationship of the individual with the group, because without this cooperative symbiosis, progress cannot be made—Judo is a co-operative activity. This spirit of cooperation is present in all facets of Judo, and therefore also of JUA. Respect for the partner is transformed into solidarity and personal responsibility towards the other and the group, generating a relationship of trust. In a Judo session, cooperation is continuously present, Judo being an activity that is done in pairs and in which all the participants of the classes interrelate with each other. Help is continually received from the higher grades, who are committed to the progress of the group and all its components, which favors the learning of the less experienced judokas [

19].

Taking into account the above, we can name this contribution of Judo to society, contextualized for older adults, JUA, and define it as the form of Judo which, on the foundations of Kodokan Judo, develops specific adapted motor skills that allow integrating norms and habits of life to contribute to the well-being of the older adult, providing autonomy in personal, domestic, and social contexts [

20]. The adapted work of the elements and technical contents of Judo provides the older adult population with an improvement of the general physical condition and the maintenance of motor skills as well as dynamic and static balance work, coordination work, proprioceptive work, and of course cognitive work. As a whole, all the work present in the techniques of Judo help to maintain and improve the performance of functional motor qualities, while the principles, foundations and methodology used contribute to a positive perception of health, giving the participants a positive development of their self-esteem and personal safety, which in turn has an effective impact on the cultural process of socialisation and personal acceptance.

In summary, we can specify the priority objectives of this program of physical activity, health and personal growth, based on the Adapted Judo Utility as follows:

To promote the practice of Judo as a specifically adapted physical activity and a healthy habit for the target population;

To promote the practice of Judo in a trans-generational way (grandparents-parents-children) as an element of socialisation and improvement of the quality of life for the older adults;

To improve the physical condition and health of older adults, favouring the execution without difficulties of the tasks of everyday life and diminishing the risk factors with respect to falls;

To put into practice the Adapted Utilitarian Judo program as an educational element in the teaching of fall control to minimise the damage produced by the impact of the body against the ground in case of fall’

To teach older adults to get up in case of a fall and know how to act correctly and calmly after it, minimising the risk of subsequent injuries’

To maintain physical and psychological balance, increasing well-being, emotional stability, and self-confidence.

1.2. JUA for the Treatment of Falls in the Older Adult Population

As mentioned in our introduction, falls are a serious problem for the older adult population. JUA offers a new and different vision with respect to existing programs in the field of prevention; so that in addition to doing everything possible in the environment to prevent the fall from occurring, JUA focuses on what actions can be taken when the fall occurs in a physical sense in order to reduce the risk and increase the safety of older adults.

In relation to falls, the WHO itself, in its Descriptive Note of January 2018 [

21], shows its concern about the risk of injury caused by falls in the elderly population and points them out as the second worldwide cause of death due to accidental or unintentional injuries, linked to the 37.3 million annual falls whose severity made medical attention necessary, which makes them an important global public health problem, with those over 60 years old being one of the main risk groups. Amongst the many consequences of falls, the associated death rate is the one with the highest impact, and according to the latest report of the Center for Research and Prevention of Injuries (CEREPRI) [

22], it is estimated that, in Europe, there are 40,000 annual deaths per year due to falls of elderly people. In addition, it is estimated that for every person that dies as a result of a fall, 24 have to be hospitalised and operated on as a consequence of a fracture of the femoral neck (960,000 annual hip fractures), while another 100 adults suffer serious consequences (4,000,000 a year), and approximately 1000 elderly people have different types of consequences and sequelae (40,000,000). This corollary of injuries, psychological problems, and sequelae with various degrees and types of disability, represents a great barrier to achieving active and healthy aging in the older adult population, since approximately 25% of the people who have been affected by an injury caused by a fall suffer sequelae such as a decrease in mobility or the Fear of Falling syndrome that, in the short and medium term, constitutes one of the causes directly related to the entry into the areas of frailty and dependency.

The proposal of practicing JUA to improve the quality of life and health of the Older Adult population has, amongst its main interests, the overcoming of the problem posed by falls in the Older Adult population. The interventions focused on the realisation of physical activity have shown their effectiveness, and that it is possible to delay and, in many cases, reverse fragility and dependence. The same goes for the practice of Tai-Chi, which can help reduce the risk of suffering a fall in the older adult population [

23,

24]. However, despite the fact that we carry out preventive interventions and work on the physical condition of the elderly, they will still be subject to the risk of falling and this is where JUA represents a unique intervention, proposing strategies of action to fall safely and securely, to retain mobility on the ground (once the fall has occurred) and to get back to a standing position.

During the bibliographic review carried out in the main scientific databases, no evidence was found of interventions in which the research was focused on the teaching and training of responses and active prevention strategies, that is, to reduce the harmful consequences caused by a fall when it occurs. This is the great contribution of JUA, which has led us to design a program that, through the adaptations of the teaching techniques of Judo falls, presents a double output: on one hand, the creation of a program that could be included as exercises in sessions of physical conditioning directed at older adults, helping to reduce the fear of falling; and on the other hand, the transformation of a traditional martial art such as Judo into a global program of healthy physical activity focused on the older adult population.

We can highlight the following specific elements of the JUA (the specific action in strengthening the prevention of falls, of its consequences and in the work on elements that have often not been taken into account, or are scarcely present, as part of the global treatment of falling):

The application of the Judo break-fall techniques, based on the reduction of the magnitude of the impacts that are generated on the organism [

25,

26,

27], contributing to diminishing the risk of injury, or its severity, which can be a promising tool in reducing the frailty of older adults;

The different components of unintentional falls in the study population also make it necessary to take into account the work of functional mobility skills on the ground, the transition to positions of safety, sitting, and getting up after suffering a fall, always based on functional and security criteria;

The methodology used, the contents trained, and the characteristics of Judo provide participants with a positive development of their self-esteem and personal safety, which in turn has a positive impact on the process of socialisation and personal acceptance.

2. The Practice of Adapted Utilitarian Judo

In what follows, we highlight some of the key practices of JUA, its fundaments are presented through some of the interventions carried out on this adaptation of traditional Judo, in which the designed theoretical model is adjusted to its practical application in different groups of Older Adults. In order to verify empirically that the proposal works properly, interventions have been made with different groups of older adults in different associations and public and private institutions (Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente Association, Association of Women for Training and Employment of Seville and Castilleja de la Cuesta, Center for the Elderly of the Center District of the Health Service of the Junta de Andalucía, JUA Working Group, created ad hoc by the Research Group of the University of Seville, to develop the program in the facilities of the subject of Combat Sports, of the Faculty of Education Sciences). From the data collected during the abovementioned interventions, encouraging results have been obtained, for example in the reduction of the Fear of Falling (FOF). This data has been presented in different international congresses such as the 7th Exhibition of Judo Research in Kazan (Russia), the IX International Congress of the Spanish Association of Sports Science in Toledo (Spain), and more recently in the 7th International Congress of Physical Sports Activity for the Elderly in Malaga (Spain).

In the methodology used for the implementation of the JUA classes, special care has been taken to consider the special characteristics of the target population, to facilitate the progression, making it accessible to as many participants as possible, saving individual limitations (inclusive Judo) while at the same time avoiding the aspects that are not adequate for the target population, which do not match the objectives of functionality, health, and quality of life. Specifically, it has been aimed at a sample that is classified as healthy or pre-frail [

28]. The reasons that have been considered to limit the participation in the activity have been a contraindication of the practice of physical exercise, congestive heart failure, vertigo or angina during physical activity, chest pain, and non-controlled high blood pressure. The intervention has been aimed at people over 60 years of age, without distinction of gender, who have not been diagnosed with diseases that impede the practice of moderate physical exercise, and who possess general mobility of the coxo-femural and scapula-humeral joints and of the spine, which allows them to perform the proposed exercises.

The intervention with the groups of older adults is organised following the structure of a traditional Judo session in order to take advantage of the extra motivation that this practice might generate by offering both health benefits and fun, which will be published in a future paper [

29]. To design each proposal, in terms of timing, the start and development have been integrated into the pre-existing academic and sports programming schedules, to provide users with better access and assistance to the activity. With this approach, quarterly cycles of 36 sessions each have been programmed, giving an average of two classes per week, with a duration of 50 min per class. With this minimum organisation, it is intended to create a practice that is significant, sufficient, and that achieves ascription to the activity. The sports facility and materials used do not require adaptations. JUA’s practice is possible in any dojo or installation in which Judo is practised with low density gym mats being the only essential auxiliary material. The significant adaptations are made in the technical elements of the art and also in the execution of movements, starting from the contents of the black belt program and the Judo Katas, which are adapted to the abilities and functional needs of the participants. Specific adaptions are focused on avoiding any exercises that could pose a risk for the older adult population, as for example, eliminating the throws and replacing them by exercises in which older adult, assisted by companions, are taken from a standing position all the way to the ground.

The adapted method focuses on the multifunctional work already present in the foundations of the art: balance, imbalances, balance recoveries, fundamental positions, ways of moving in all directions, grips, coordination sequences, global and analytical movements, fine and general motor skills, maintenance work of the range of joint mobility, etc. The traditional system of teaching and practice of Judo is followed, in which the study with a partner stands out as fundamental, that is to say studying in pairs (standing, moving, alternating, freely, lifting or not, pulling or not, performing Katas, etc.), but as we have previously pointed out, to guarantee the safety of the older adults, in the process of adaptation, throws have been transformed into a proper system for teaching the correct technique to go to the ground in a soft and protected way. Below, we identify a range of the adaptions currently being implemented and researched.

Let’s Start by Dressing Up to Do Judo

When we start practicing any physical activity or sports, we must have appropriate clothing, in this case a Judo suit or “Judogi”, which is composed of a resistant fabric jacket called “Ugawi”, wide trousers with reinforcements in the knees called “Zubon”, which adapts to the waist with an elastic or cord, and of course the belt that is called “Obi”. The Japanese culture places great value and importance on the rules of etiquette, even for simple things, like the way to tie the belt or the correct way of putting on the jacket or “Ugawi”, so we start the session dressing ourselves correctly for the Judo class. The signs of respect for the norms and for the cultural tradition of another country contribute to the fact that within a collective activity such as Judo, there is a sense of integration in the activity and of belonging to the group, facilitating interpersonal relations and communication while at the same favouring the development of cooperation and cohesion. The traditional Judogis are white, and in the JUA, they can be of a reduced grammage, which reduces their weight and increases comfort. The use of comfortable sports clothing underneath is also allowed, as well as the use of sporty white socks or shoes suitable for use on the tatami, which is the term used to refer to the padded area where we practice Judo, while the training place as a whole is called Dojo. The use of traditional judogi gives the participants a feeling of integration in the activity and in the group from the beginning.

We begin by adjusting the judogi jacket by placing the right lapel below the left. Next, we hold the belt by the centre, and place it on our abdomen, about four fingers below the navel, then slide both ends towards our back, letting the belt slip inside our hands. Our hands meet at the centre of our back and we exchange the sides of the belt that we are holding. We take the ends of the belt back to the front, and we make the right end go under the belt and come out from the top. The end that has been left down, on the right side, passes over the other end wrapping it and passing through the “eye” that has formed. Finally, we stretch the two ends in opposite directions horizontally. Putting on the judo belt, in addition to helping the participants “get into the dynamics of the activity”, is a very interesting exercise for the fine motor work of the fingers of both hands (

Figure 3).

The colour changes of the belt represent the path that the Judo practitioner goes through in their learning, and they represent the recognition of perseverance, work, experience, and acquired knowledge. As a consequence of the continued practice, the older adult obtains the official Judo belts, which culminate in obtaining the Judo black belt of experience, as a reflection of the achievements obtained through the program, but also as a sign of respect for and recognition of the effort and participation in JUA. This dynamic of recognition of results in short and tiered terms reinforces the attitudes of generational and inter-generational socialisation in the group and benefits the self-esteem, security, personal autonomy, and by extension the quality of life of the participants.

3. Fundaments

3.1. Let Us Start the JUA Session

Once we have put on our Judo suit and belt, we initiate the Judo session with the Traditional Salute (Reiho), and continue with the contents of the Judo fundaments, which are introduced as part of the warm-up. In this initial part of the JUA session, we practice the fundamental postures that are used in the practice of Judo or “Shisei”, the fundamental holds or “Kumikata”, the ways of moving “Shin-tai” that are practiced in all directions, and the “Kuzushi” or imbalances, in which we include work of high functional utility in recovering stability.

3.2. Reiho (Greeting)

This is what the greeting rules are called. In Judo there are two forms: the standing salute called Ritsurei and the kneeling salute that is called Zarei. The greeting is a norm of courtesy and respect among Judo practitioners, with which we show our gratitude to our colleagues, with whose collaboration we will practice and improve our technique. It is always done when entering and leaving the tatami and when starting and finishing the Judo session, as well as before and after working with any partner. The adaptation required by the greeting is simple, if a participant cannot kneel he or she salutes standing, they can also put a single knee on the tatami (

Figure 4), or they can be helped by the judokas at their sides to adopt the zarei posture, to salute on the ground, or to return to their feet with greater comfort and safety.

3.3. Shisei (Fundamental Positions)

Body position, of which there are two fundamental forms: the natural position or Shizen Hontai and the defensive position or Jigo Hontai. The natural position or Shizen Hontai is fundamental to correctly perform the movements and Judo techniques to offer greater mobility. But its main value for the older adult population comes from the work of stability and control of the trunk. Working on postural correction avoids the forward fall (inclination) of the trunk and, with it, the instability due to the displacement of the body’s center of gravity, which is often caused by the tonic reduction of the lumbar back musculature. Thus, it is a good maintenance exercise and retraining of postural stability. From the position of the standing salute, we place ourselves in the natural position (Shizen Hontai), from which we move to the right natural position (Migi Shizentai), repeating the movement several times, first advancing the right foot, and later moving back the left foot (always passing through Shizen Hontai). Then, starting again from Shizen Hontai, we perform the same sequence to adopt the natural position left (Idari Shizentai), this time advancing the left foot, and later moving back the right foot (always passing through Shizen Hontai). The Jigo Hontai defensive position is more stable by increasing the base of support and lowering the center of gravity, so it constitutes an effective dynamic strength training of the legs (

Figure 5). In addition, we decrease the height preparing the strategies of recovering the dynamic balance and, if applicable, the control of the adapted fall.

We start from the natural position and adopt the defensive position (Jigo Hontai), from which we adopt the defensive right position (Migi Jigotai) and defensive left position (Idari Jigotai), following the steps described in the previous paragraphs.

3.4. Shintai (the Movements)

When we walk, we constantly modify our body position, moving our weight from one leg to the other, which generates a (controlled) instability and an imbalance caused by the constant movement of our center of gravity in the direction of the movement. In Judo, the movements are called Shintai, and they are designed to maintain stability and avoid losing balance, allowing us both to defend ourselves from the opponent’s attacks and to perform our attack techniques. In the JUA, we start from the movements of traditional Judo, with which we consolidate the adequate ambulatory mobility, with consecutive, successive, lateral, circular steps, all of them without ever crossing or joining the feet (

Figure 6).

These fundamental forms of movement are carried out in what is called Suri Ashi, which consists of sliding the feet on the canvas, without ever completely removing them from the ground, that is, elevating the heels a little, but without separating the toes from the tatami. This aspect has required adaptation, with the aim of improving the functional progress of the Older Adult, so that in JUA movements are also carried out by elevating the tip of the foot, working the strength and mobility of the foot and the ankle in a specific way. This also serves as a base to train avoiding obstacles and maintaining or restoring stability and balance. The fundamental forms of traditional movement in Judo are two: the first, called Ayumi Ashi, is made by alternating the movement of both feet, as we usually walk. The second is called Tsugi Ashi, and in it, one foot follows the other but without surpassing it. Another fundamental movement that is practiced in Judo is the Tai Sabaki, which consists of moving the body by pivoting on one foot, causing a circular movement of the body that is fluid and fast and that allows us to maintain balance.

3.5. Kagami Migaki (Polish the Mirror)

This movement is part of the Kata Seiryoku Zen’yo KokuminTaiiku, and we introduce it as part of the functional warm-up, to work on the improvement of coordination, articulation mobility of the upper body, concentration and attention, memory, breathing, and postural control (

Figure 7).

In practice, one always starts from the Shizen Hontai position and first moves the arms outward and then toward the center (between three and five times each). Next the movement is combined with Migi Shizentai, and Idari Shizentai, starting from Shizen Hontai: with the elbows open, one raises the hands in front of the chest and, continuing upward, draws a large circle outward while advancing one foot. When returning to the starting position, one makes the movement inward. It is done only once on each side and then again on each side, following the same pattern but moving the foot backwards. These sequences are also performed in the Jigo Hontai position on different days.

3.6. Kumi Kata (Grips)

The fundamental grip, the Kumi Kata, is introduced from the natural and defensive positions while working in pairs, face to face, and they are done together with the work on the positions or Shisei, always taking into account not to repeat too often similar gestures or very similar patterns that make the class boring. Also, it is also recommended to practice only the basic fundamental grip in the first days. It is done keeping the palm of the left hand facing up, grasping the lower part of the partner’s sleeve at the elbow, and grasping the left lapel with the right hand (

Figure 8). In the grip exercises, we focus on three things: First, the use of the fingers for the maintenance of the fine motor skills through joint mobility exercises. Second, the work of press force in both hands. Third, the bilateral functional coordination working with both hands at the same time with a single focus: one hand offers and prepares so that the other hand can grasp effectively.

3.7. Kuzushi or Imbalance

This is one of the fundamental elements of Judo, and it is closely related to stability. When we can draw a straight line perpendicular to the ground from our center of gravity, and the final end of the line is within our base of support, we are in equilibrium. However, the closer to the outer edge of our support base that imaginary line is projected, the more unstable our position will be and therefore our equilibrium will be “more fragile”. For the same reason, the smaller our base of support, the more unstable our position will be.

The height from the centre of gravity to the base of support also plays a role in the stability and solidity of our balance: the greater this height, the more compromised our stability will be, while at a lower height we will have greater stability. Thus, we can establish that we can get our partner unbalanced when we take his centre of gravity out of its base of support in any direction. Traditionally, eight fundamental directions of imbalance are studied in Judo, which are used without any adaptation in JUA: forward, backward, left and right, and the diagonals of said imbalances; that is, back left, back right, front left, and front right. To unbalance your partner, you can use direct actions of the arms (pull or push), the Tori’s own displacements together with the direct actions of their arms (Tori is the Judoka who is performing the throw or technical action), the movements of the training partner or Uke or the displacement of Uke’s center of gravity and the generated instability postures (Uke is the Judoka that is being thrown or is receiving the action), the combination of stimuli, and the principle of action-reaction (I pull and push, I push and pull, I approach and Uke moves away, I move away and Uke approaches, I hold high and Uke crouches or bends, etc.). This whole “game” of imbalances has huge functional potential and allows us to discover the sensations of instability that occur before the imbalance takes place, and, from these feelings of kinesthetic enrichment, work on the functionalities of instability reduction, stationary and ambulatory safety, and personal rebalancing (

Figure 9).

After the oscillation that causes the imbalance (kusushi), we train adequate responses, replacing the resistance and rigidity, which are adopted to maintain the original up-right position, by modifying the base of support, moving the projection of the centre of gravity by means of the displacement (Shin-Tai) of the points of support and, at the same time, increasing the stability by lowering the centre of gravity and modifying the posture. In short, we can see how the different studied fundaments of Judo are integrated into a response that groups the different principles that have been used during the JUA session.

3.8. Ukemi Waza (the Falls)

They form the element that required the most adaptation in JUA. The work will always start from the position of lying down and with the help of one, two or more colleagues, to offer the assurance of the assistance designed for the execution of the Ukemis, establishing from the start the basis of the learning process and progress through collaborative work (

Figure 10).

Judo falls are classified into backward or Ushiro-Ukemi falls, lateral or sideways Yoko-Ukemi falls (Migi on the right, Hidari on the left), falls forward without rolling or Mae-Ukemi, and forward rolling falls called Zempo Kaiten-Ukemi or Mae-Mawari-Ukemi, also performed both from the right and the left. With the Ukemi work (which is always adapted), we begin to learn the supports and basic assistance, so we can start with the movements of dynamic assimilation of the falls, always including the adaptations and the appropriate security elements to avoid injuries and to prepare the body, automating the technical gestures through progressions of educational functionality (

Table 1).

4. JUA Techniques

As in Judo [

30], we can establish three large groups for the technical work of JUA. First of all, Nague Waza is a group that includes throwing techniques. In these techniques the most significant adaptations made are those related to Ukemis, which are transformed from energetic projections into soft, controlled and safe ways to take the opponent to the ground. Second, Katame Waza referes techniques of controlling the opponent, which are integrated with the techniques of immobilization or Ossaekomi Waza, the strangulation techniques or Shime Waza, and the techniques of dislocation or Kansetsu Waza.

This group of techniques requires adaptations that are very simple and not very significant, of which it should be noted that both the Shime Waza and Kansetsu Waza are executed as forms of control over Uke and never of submission, so they are smooth movements. However, it does contain a significant amount of utilitarian functionality for the target population, and a large part of Katame Waza’s techniques are performed on the ground (kneeling, sitting or lying down), and it is through this work on the ground that the older adult develops strategies of mobility and reincorporation, providing the older adult with an effective system to move on the ground and stand independently and safely if a fall occurs. Finally, Atemi Waza, the beating techniques. They are the least known part of Judo, due mainly to the fact that in its sporting aspect, the use of the Atemis is prohibited, and it is only used in the katas and in the side of Judo that focuses on self defence, not requiring any adaptation for its application to JUA classes.

To describe all the contents of Judo is neither possible nor the objective of this paper and would require much more space, but it is appropriate to say that all the official contents of Kodokan Judo are suitable for use in JUA with the adequate adaptations for each person (

Figure 11).

5. The Katas

Finally, Judo has as its most traditional element the Katas [

31], which literally translates into “forms”, and they are practiced as a system of pre-established techniques and subject to rhythms of execution. They are a way of studying defence and attack in a systematised way, and apart from containing judo techniques, the Basic and Fundamental Forms to preserve the essence of Judo are present within them. It is generally accepted to classify the Katas into four groups:

Nage No Kata, in which throws are practised, and Katame No Kata, in which the Katame Waza principles or control techniques are developed.

The Katas dedicated to Self Defence, which are the Kime No Kata and the Goshin Jutsu No Kata. The first includes some traditional defence techniques and the second considers more modern self-defence techniques.

Physical education Katas. The Ju No Kata, or Kata of Flexibility and the Seiryoku Zen’yo Kokumin Taiiku, which is translated as the Kata of the National Physical Education of Maximum Efficiency.

Theory of Judo, with the Itsutsu No Kata or Kata of the Five Principles, and the Koshiki No Kata or Kata of the Ancient Form.

Some of these Katas do not require any type of adaptation, such as the Ju No Kata or Zen’yo Kokumin Taiiku No Kata, as they are “soft forms” of execution. Both in the techniques that are performed and in the rhythm of their practice, the coordination and harmony between Tori and Uke stands out in these Katas. In the rest of the Katas, as with the contents of the Judo techniques, the adaptations that are introduced are personalised according to the particular needs of each practitioner, with the execution of the ukemis being most significant: they are carried out with all the necessary prevention to avoid any potentially harmful situation.

6. Concluding Comments

It should not be forgotten that JUA’s structure understood as “physical culture” is intended as a cross-cultural and intercultural activity designed for an older adult population and that is valued by them as healthy and fun. Thus, JUA offers a comprehensive and meaningful physical cultural activity to enhance the participants’ physical condition, improving their ability of maintaining balance, of functional walking, of coordination and memory, introducing elements of generational and intergenerational socialisation, all of which, as can be seen from numerous studies, result in the increase of self-esteem, safety, personal autonomy, and by extension in the quality of life of the participants.

JUA practice also offers the opportunity for active and relevant participation of older adults, as specially qualified volunteer staff, in the organisation of activities related to Judo, which could be called voluntary black belts, to contribute to specific aspects of control and organisation of sports competitions and activities related to Judo.

Focusing its application on the formative process that is generated in its group and directed practice, JUA allows us to carry out trans-generational work (grandparents-parents-children) with the adhesion of a population usually excluded from Judo. The adaptation of the contents of Judo allows for highly socialising work between, for example, the joint practice of grandparents and grandchildren together in the same physical and temporal space. The Judo class starts and ends with the greeting that all the participants perform at the same time, but while the children practice recreational or competitive Judo, the older adults do their JUA training, with a large part of the elements that are practiced coinciding, being equal or very similar in content, but with different intensities, rhythms and objectives. One way of introducing these dynamics is by organising days for grandparents and grandchildren, in which the older adults share the class with their grandchildren, taking into account that it may be the grandparent that accompanies their grandchild who participates in Judo classes or that it is the grandchild that accompanies their grandfather who practices JUA. In both cases, the day of Grandparent Judoka is celebrated.

It is worth pointing out the possibility that the JUA proposes to offer society a specially practical orientation of active prevention of falls, which can open the practice of adapted Judo to the field of health and the improvement of the quality of life, keeping within the activity design and contents a vocation of maintenance and improvement of the functionality and autonomy of older adults with respect to the performance of the basic activities of daily life and the instrumental activities of daily life. Aspects such as the effect that the practice of JUA can have on the reduction of the Fear of Falling Syndrome (FOF) require control and analysis of the results through validated instruments, such as the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale [

32] or the Falls Efficacy Scale-International [

33], since there is evidence of the direct relationship of FOF in older adults and the practice of physical activity programs [

34]. The size of intervention groups should be increased, as well as the number of participants, and the time of its implementation should be prolonged.

As a future perspective, we believe that older adult care and health professionals should include JUA as an innovative, social, and recreational component in the contents of physical activity programs focused on active aging and the prevention of fragility of older adults. Adapted Utilitarian Judo presents a conceptual reflection of traditional Judo, Judo Kodokan, maintaining the philosophy of the culture in which it was born, and transferring it to a modern western context.