Abstract

Several studies have observed a syndrome of shifting values within different cultures over the past five decades. This work investigates whether these cultural changes have been followed by changes in individual attitudes regarding state authority in Brazil. Using data from the World Values Survey, we tested the hypotheses proposed by Ronald Inglehart that the increasing prevalence of self-expression and secular-rational values has been followed by an increasing societal emphasis on civic autonomy over state authority. The results do not provide evidence to support this hypothesis for Brazil. Instead, the study shows a stable pattern of support for state authority in the past three decades despite the increasing level of self-expression values. The study suggests that these attitudes are related to long-lasting characteristics of the political culture and public expectations regarding the role of the state in reducing social inequality in Brazil.

1. Introduction

The extensive work of Inglehart [1] and Inglehart and Welzel [2] identifies a syndrome of value changes around the globe and presents several hypotheses about the prevalent values in societies after the completion of large social and economic shifts during the 20th century. The present study tested one of these hypotheses regarding social support for state authority. According to Inglehart and Welzel [2] (p. 292) , “Favorable existential conditions contribute to emerging self-expression values that give individual liberty priority over collective discipline, human diversity over group conformity, and civic autonomy over state authority”.

Most countries in Latin America experienced relatively fast economic and social development in the last few decades of the 20th century. These developments led to a wide provision of “favorable existential conditions” in society and to an increasing predominance of self-expression values, particularly among younger cohorts. Using data from the World Values Survey (1981–2014), we tested whether the emerging self-expression values in Brazilian society were also followed by an increasing emphasis on civic autonomy over state authority, as expected. The period chosen, the 1980s to 2014, is particularly relevant for this research as Brazilians experienced a generalized increase in income, educational level, and life expectancy that promoted more favorable existential conditions for most of the population. At the same time, this is a period of transition from a dictatorship to a more consolidated democratic regime.

Before presenting and discussing the results, this article further explores the theoretical and empirical framework used by Inglehart and Welzel, which is the main reference for the hypothesis proposed in this study. This is followed by a general review of the economic and social development of Latin American countries during the second half of the 20th century and the general trends regarding the political culture in these societies. The final part of this paper presents the results of the analysis on the public support for the state authority in Brazil using data from the World Values Survey.

The idea that socially shared values, orientations, and attitudes are fundamental for understanding the political world dates to the works of ancient and modern thinkers such as Plato, Rousseau, and Tocqueville. However, only in the 1960s, with the development of the concept of “political culture” presented in the work of Almond and Verba [3] did this idea come to be operationalized and empirically studied in political science.

Almond and Verba [3] (p. 13) proposed that “the political culture term refers to the specifically political orientations—attitudes towards the political system and its various parts and attitudes towards the role of the self in the system”. The suggestion of this concept represented an emblematic development for studies in the field of comparative politics, given that it operationalized a cultural dimension aspect, hitherto intangible, and formed the basis for a series of empirical studies using surveys as a comprehensive method to assess political culture.

A customary critique of the concept of political culture focuses on its inability to address social and cultural change. In fact, at least until the 1980s, the idea of a fixed cultural and social structure that determines political socialization was prevalent within this field. In other words, political culture studies contain more considerations regarding the permanence and immutability of the culture than reflections about the adaptability and evolution of this dimension. In part, the emphasis on stability is one of the advantages of political culture theory, as it points to the autonomy of the political culture as an explanatory variable, independent of the political system or the social and economic situations. On the other hand, if the association of the political culture with the political system is true, changes in the political system should necessarily be accompanied by changes in the political culture.

Following a similar rationale, Eckstein [4] and Inglehart [1] offer explanations that aim to envisage the idea of political change within the theoretical and methodological framework of political culture. For Inglehart, the change in political culture is the result of an intergenerational process of transformation. As major changes occur in social, political, and economic structures, new generations shape their worldviews in a world with new characteristics, different from previous generations. Based on the theory of political socialization, which emphasizes the reproduction of the same political guidelines, Inglehart also makes use of the assumption of scarcity to explain individual political formation. According to this hypothesis, the priorities of human action are the result of the current socio-economic environment, in which there is a strong subjective valuation to things and aspects of reality that are not well developed or are in shortage. For instance, if there is a lack of physical security in a given society at a specific time, a violent environment, or a high perception of violence, individuals tend to put more value on physical security and prioritize a safe environment more.

Taken together, the hypothesis of political socialization and the hypothesis of scarcity produce a basic model of value formation in which individuals’ values are prioritized in an early period of their life and tend to follow general guidelines acquired from their family or school life but also reflect the socio-economic environment of the socialization period. This articulation of hypotheses explains the basis for the emergence of new political values and orientations in advanced industrial societies.

In more recent work, Inglehart and Welzel [2] argue that according to political culture theory, changes in values can be observed in two main dimensions: one that expresses the change from traditional values to secular-rational values and another that represents the continuum between survival values and self-expression values.

In this study, we rely on the robust work performed in the field of political culture that demonstrates that major economic, social, and political processes can change collective perspectives about the political world; i.e., they can influence political culture. Based on that, we proceed to a brief analysis of the changes in the Brazilian political culture over the past three decades and how they are related to the social views regarding state authority.

2. Methods

The main question addressed by this investigation is the following:

Is the increase in post-materialism and self-expression values accompanied by a decreasing emphasis on government responsibility in Brazil?

Based on Inglehart and Welzel, the answer should be positive, i.e., there will be an increasing emphasis on civic autonomy over state authority as a result of the same social processes that induce the emergence of post-materialism and self-expression.

We have used data from social surveys based on national representative samples to test this hypothesis. The results of the empirical analysis are described below. The first part analyses the hypothesis of the increase in post-materialism and self-expression in Brazil. The second part explores the social support for the state across different waves of the World Values Survey in Brazil.

2.1. Post-Materialism and Self-Expression in Brazil

2.1.1. What Is Post-Materialism?

Before testing the hypothesis for the Brazilian case, it is important to clarify the concept of post-materialism and confirm its increasing preponderance among Brazilians. In a seminal study covering six European countries, Inglehart [5] identified an intergenerational change in the core values of these societies. Among older individuals, he found a preponderance of materialist values, and among younger individuals, post-materialist values were more prevalent. The following question was used to measure and operationalize these concepts [5] (p. 994): If you had to choose among the following things, which are the two that seem most desirable to you? Maintaining order in the nation; giving the people more say in important political decisions; fighting rising prices; protecting freedom of speech.

Considering the six possible answers for this question, the choice of the pair “maintaining order in the nation” and “fighting rising prices” identified “materialist” perspectives, while the choice of the other two alternatives identified “post-materialist” perspectives.

2.1.2. Is Post-Materialism and Self-Expression Increasing in Brazil?

Over the six waves of administration of the World Values Survey, in most of the countries, the percentage of the population with post-materialist values increased. In Brazil, the proportion raised from 7% in 1991 to 12% in 2014. This difference is higher among the age group of 18 to 29 years, changing from 8% in the first wave of the Brazilian survey to 18% in the last one. The validity of the post-materialism measurement, as well as the mentioned increase among Brazilians, is confirmed by a more thorough analysis conducted by Ribeiro [6].

Throughout the decades, the methods to identify and measure value change in different countries became more sophisticated. In a more elaborate version of this work, Inglehart and Welzel [2] advocate that human development can be characterized as a movement from traditional and survival values towards secular-rational and self-expression values. Traditional values are defined as a combination of different attitudes and beliefs, such as that God is very important for one’s life, that it is important for a child to learn obedience and religious faith instead of independence and determination, that abortion is never justifiable, and that national pride and respect for authorities are important. Secular-rational values express the opposite of these traditional values. In a complementary dimension, human development is also considered a departure from survival values, which represent the prioritization of economic and physical security over self-expression, tolerance and participation. This is the view on the human development that was adopted by the present study to investigate the impact over political values.

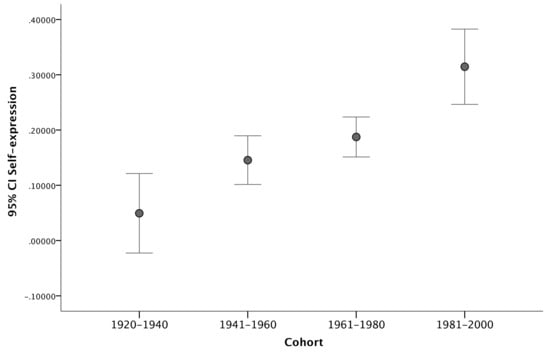

To assess and measure this perspective of human development, the authors propose an index for each dimension based on a combination of several variables of the WVS. As with the post-materialists’ increase, the authors also verify a broad movement of human societies in the direction of secular-rational and self-expression values. In Brazil, the national average of the index for self-expression increases over the four waves of the WVS. The difference in the averages are higher compared with the pseudo-cohorts1 of the Brazilian respondents using the data from the four waves together. Chart 1 shows the mean, with 95% confidence interval, for the self -expression index in each cohort. The self-expression index for the oldest cohort (generation born between 1920 and 1940) is significantly lower than that for the youngest cohort (generation born in 1981–2000). The same pattern can be observed when the general population is compared for each wave. The average value for the index in the sixth wave is equal to 0.26 whereas the average for the second wave is equal to 0.03. This comparison provides evidence for the increasing prevalence of self-expression over time, as the main hypothesis suggests.

Chart 1.

Error bar (95% C.I.) for the means of self-expression among different cohorts (WVS). Source: World Values Survey 1981–2014 Longitudinal Aggregate v.20150418. World Values Survey Association (www.worldvaluessurvey.org). Aggregate File.

As expected, this trend of rising self-expression is indeed coherent with the social development experienced by Brazil in the last decades. The number of households in which the family income was below the poverty line fell from 12.1 million in 1990 to 6.4 million in 2014.2 The percentage of the Brazilian population “satisfied with the financial situation of the household” (choosing 6 to 10 in a 10-point scale from WVS) rose from 47% in 1991 to 59% in 2014. In addition to information on the financial situation, WVS also provides information on life satisfaction in general. In the same format of the previous question, 75% were satisfied with their life in 1991, while 82% were in 2014. Notably, this increase is observed mainly at the highest point of the scale (10), where the percentage rose from 28% to 33%.

Therefore, the evidence provided by the WVS data succeed in confirming the expected increase in the emphasis on post-materialist and self-expression values among Brazilians, especially the younger generations. The next section of this article aims to confirm whether this increasing emphasis on self-expression was also followed by a decreasing emphasis on state authority.

2.2. Support for the State in Brazil

The idea of the state in this work is aligned with most modern political theory perspectives that emphasize the opposition between the individual and the collective apparatus responsible for maintaining the order in each society. However, the “state” here is deliberately employed with multiple meanings, as the term may have many connotations for individuals within a country and across cultures. In this sense, as mentioned by Schmitter [7] (p. 33), a modern state can be considered “an amorphous complex of agencies with ill-defined boundaries performing a variety of functions not very distinctive”.

Thus, in line with the objective of this study, it is important to note that there is a multiplicity of meanings that the idea of “state”—used in a manner equivalent to the term “government”—can take regarding the view of the average citizen. Moreover, this work will highlight the dichotomy between the state and individuals in the social imaginary and subsequently perform a theoretical assessment of this imaginary.

This perspective is also aligned with the use of the term “state” in the works of Ronald Inglehart. In a broad sense, the main purpose of this work is to investigate the “shifts away from both religion and the state to the individual, with an increasing focus on individual concerns” [1] (p. 197).

In addition to the WVS, which has been administered since the 1980s, the Americas Barometer of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) also contains relevant data on this theme. Both projects ask similar questions about the specific object of study of this work. As described in the Table 1 below, both the WVS and the AmericasBarometer include a question that places respondents’ opinions on a scale and creates a continuum between the individual and the state authority.

Table 1.

Questions related to social support for the state.

Despite the use of different statements, the results from the WVS in 2014 and AmericasBarometer in 2012 are consistent given that the mean for the 10-point scale of the WVS is equal to 7.0 (s.d. 3.2), while the mean for the 7-point scale of the AmericasBarometer is equal to 5.5 (s.d. 1.6).

Another cross-sectional survey, Latinobarômetro, has included a similar question asking Brazilians whether they think that the state can solve problems in our society. In 1998, around 30% of the respondents mentioned that the state can solve all or most of the problems in our society. In 2010, this percentage was higher than 61%.

Also, the WVS variable is positively correlated with confidence in institutions such as armed forces, parliament, the government, and political parties, as well as with the level of agreement with the statement that “government ownership of business and industry should be increased”. These correlations indicate that the selected variable tend to capture the support for state authority.

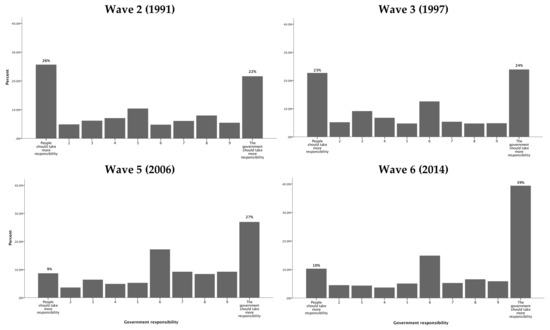

This variable from the WVS (subsequently “GovResp”) has been included in the questionnaire since its first wave. There are clear differences among surveyed populations over the four decades of administration. In Brazil, the percentage of missing values for this variable was less than or equal to 1%, except for the first wave, in 1991, in which 2% of the respondents did not provide a valid answer. Chart 2 shows the percentage of the answers for each point of the scale in the four waves of the WVS. In 1991, 26% of the respondents selected (1) “People should take more responsibility”, and in 2014, this proportion decreased to 10%. In looking at the distribution of this variable over the four waves, it is possible to notice that most of the answers became skewed towards the right side of this scale (observations closer to 10).

Chart 2.

Distribution of GovResp in Brazil—4 waves (WVS). Source: World Values Survey 1981–2014 Longitudinal Aggregate v.20150418. World Values Survey Association (www.worldvaluessurvey.org). Aggregate File.

The analysis of GovResp as a quantitative variable reveals a significant difference between the averages over the different waves of the WVS. In 1991, the average was 5.3 (s.d. 3.5) considerably lower than in 2014, with an average of 7 (s.d. 3.2).

Even using different strategies, it was not possible to identify a pattern suggesting a decrease in the emphasis on state authority over time. Similarly, the level of confidence in institutions such as armed forces, civil services, and government remained stable over time, with at least 45% of the population stating that they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in them. This evidence from the Brazilian case leads to a problem not described or expected by the approach of political culture change and human development explored before. However, the work of Raymundo Faoro regarding the patrimonial state provides useful insights to understand this apparent contradiction.

3. Discussion

Raymundo Faoro conducts an extensive analysis about the Brazilian political tradition and the role of the Brazilian State. To Faoro, patrimonialism is one of the main characteristics of the Brazilian political formation and an influential force in all major political changes in the country’s history, from D. Joao I until the Vargas Era. Following a Brazilian social theory tradition that emphasizes the enduring influence of the Portuguese colonization in Brazilian politics, Faoro argues that.

The problem would not be relevant to this essay if feudalism would not have left, in its funeral cortège, a lively and persistent legacy, capable of guiding the path of the modern State. Patrimonial and non-feudal, in the Portuguese world, whose echoes resonate in the current Brazilian world, the relationships between man and power are different, as well as the economic order is of other nature, still persistent, obstinately persistent.[8] (p. 33)

Considering this approach, which highlights the patrimonial characteristics of Brazilian politics, Raymundo Faoro elaborates the concept of “politically oriented capitalism” to explain the advent and development of this patrimonial order. To Faoro, the individualism found in political systems derived from bourgeois revolutions at the end of feudalism—absent in the Iberian Peninsula and Brazil—had to be replaced or incorporated in this context where the state drives capitalism. In this sense, the author describes the political formation of a country whose history is characterized by a profound social inequality. In his words,

Two juxtaposed categories coexist, one refined and literate, another, primary, given to their primitive gods, among whom, now and then, the good prince is incarnated. […] people want the protection of the State, parasitizing it, while the State maintains the popular minority, prevailing over them. On the psychological level, duality oscillates between disappointment and deception. […]. In the sovereign, all the hopes of the poor and the rich are concentrated, because the State reflects the driving force of society. The subject wants protection, not participating in the collective will, protection to the underdogs and the producers of wealth, in the ambiguity essential to this type of dominance.[8] (p. 875)

In fact, according to WVS data, the characteristics of those individuals who locate themselves closer to the statement in favor of the state authority are similar to these characteristics described by Faoro. Comparing respondents who are more prone to support the state3 with the rest of population, we find higher percentages of less educated, female, young, and non-white people. This finding presents a valuable contribution to the discussion as it suggests why, despite the increasing occurrence of self-expression values, the state continues to be the focus of the popular hope in a context of acute social inequality.

Reviewing Faoro’s work, Fernando Henrique Cardoso [9] (p. 73) states that he agrees with Faoro’s emphasis on the power of the patrimonialist state and the culture that supports it, although he believes that there is an opposition to this culture coming from increasing “values of freedom and individualism in society”. Almeida [10] (p. 193) also believes that a change in relation to pro-state values is in course. Despite departing from a similar diagnosis that among Brazilians there is a high level of “statism” as a result of historical processes, the author also affirms that “for those who wish less state, remains the consolation that this is the fate of the public opinion in Brazil. It is a long but inevitable process: […] the higher the education attainment, the lower is the social support for the state’s presence in the economy”. Although Almeida’s diagnosis is empirically correct, there is no evidence to support the prediction that an increase in the school attainment will directly result in a decrease of social support for the state authority [11].

At the same time, authors did not ignore or underestimate the impact of state policies over the Brazilian culture. The state acts in different ways in the construction of a political culture that is in harmony with its interests. The emphasis on the propagation and massification of nationalist and authoritarian ideologies in European countries led, for example, to the formation of political cultures (or anti-cultures) in favor of the emergence of totalitarian regimes over the course of several years in the late 19th century.

Another example is the predominance of a patronage culture that guides the political systems found in many societies, especially in Latin American countries. In these systems, the development of political ideas and practices fostered by the agents of the state are characterized by treating the relationship between citizens and the political elite as a relationship between client and employer. Rooted in the political traditions of these societies, clientelistic political culture is resilient even to the innovations of democratic regimes that propose the inclusion of civil society in the political system in other terms [12]. Additionally, even in circumstances in which is possible to identify an association between institutional innovations and change in political culture, there are no conclusive studies that indicate the direction of causality [13].

Considering the apparent contradiction detailed in the previous section, and based on Faoro’s analysis of the “patrimonial state” political culture, our proposition is that the unexpected pattern of persistent support for state authority is associated with an enduring political culture reliant on the monopoly of the state for social protection, which is even stronger in a context of high social inequality.

Unfortunately, our hypothesis cannot be fully tested due to a lack of adequate measures in the WVS to assess vulnerability and the struggle to decrease inequality. However, using proxy variables from the WVS and multiple linear regression, we tested different explanatory models for government responsibility in Brazil. The documentation detailing the variables and the procedures applied in this analysis is available as a supplementary material of this paper.

According to Inglehart and Welzel [2], the main forces that drive the movement away from an emphasis on state authority are self-expression values and civic autonomy. Two variables in the WVS dataset measure these two specific dimensions. The first is an index created to express the continuum of survival/self-expression values, called SURVSELF. The other variable is the AUTONOMY index, ranging from −2 to 2 and resulting from the aggregation of four WVS variables. This index attributes higher scores if the respondent believes that “independence” and “determination and perseverance” are important qualities for children rather than “obedience” and “religious faith”.

In addition to these variables, the models included the scale INEQUALITY (e035), which intends to identify individuals with a higher sensitivity for social inequality. This variable serves as a proxy to test the relationship suggested by our hypothesis. The scale varies from 1 to 10, in which 1 indicates that the respondent believes “incomes should be made more equal” and 10 indicates that the respondent believes “we need larger income differences as incentives for individual effort”. Therefore, lower values are theoretically associated with a more egalitarian perspective, which, in Faoro’s words, represents the hopes for protection and higher values, which are related to what Cardoso refers to as “individualism and liberty in society”.

SEX (x001), EDUCATION (x025r) and COHORT were also used as independent variables. The second variable refers to the highest level of education attained, recoded in three levels: the lower is equivalent to primary or no education, the middle level comprises those with a secondary level of education, and the upper includes those with an incomplete or complete tertiary education. The third variable, COHORT, is the same one detailed previously in this work that uses a pseudo-cohort strategy to identify different generations taking the survey. Consequently, all answers from the four waves were taken together in this analysis.

The two models detailed in the Table 2 below have very low explanatory power for government responsibility. Both have statistical significance and the regression coefficient is equal to 0.032 in the two models. This means that the two models explain only 3% of the variation in government responsibility, which was expected because of the nature of the variable; i.e., it is extremely difficult to explain variation in individual attitudes. Moreover, the high number of observations is also responsible for the high variability and hence the difficulty to find a parsimonious explanation.

Table 2.

Regression results for government responsibility.

However, the statistical model has the purpose not only to explain the variation in the dependent variable but also to test the explanatory power of each one of the independent variables. In this sense, it is possible to confirm that autonomy and self-expression, as operationalized by the variables in the WVS, are not statistically significant for explaining government responsibility. On the other hand, being a woman or young or having a low level of education are important characteristics to explain high levels of government responsibility. Furthermore, positions associated with higher expectations of the future of society (lower levels of INEQUALITY) can also explain, even more strongly, high levels of government responsibility.

The first model, which includes SURVSELF, the dimension of survival/self-expression value changes, as well as the autonomy index, has about the same explanatory power as the second model, which does not include these two variables. This result is consistent with the descriptive analysis of these variables, showing growth over time, which suggests no relationship with the government responsibility distribution throughout the four waves.

It is important to mention that the number of observations differs substantially between the two models. The inclusion of SURVSELF and AUTONOMY decreases the number of observations, as these indices result from a combination of several variables. However, an analysis of the missing values for these two variables shows no relationship with the year of the survey, gender, education level, or age.

4. Final Considerations

The “end of history” became an emblematic expression for a set of views of social scientists at that time who interpreted the economic collapse of the Soviet Union as a final stage—or aim—of human political development. The lack of ideological alternatives and the relative success of liberal democracies served, as per this view, as solid evidence that human societies were walking towards a common political model characterized by a diminishing authority of the state in regulating the economy and other aspects of social life.

A critical perspective of this teleological view—i.e., of societies evolving towards a model of liberal democracy—was presented by Samuel Huntington [14] with the “clash of civilizations” idea, which argues that cultural differences between human civilizations tend not towards uniformity but towards the reinforcement of the cultural characteristics from each of these civilizations.

In response to Huntington’s argument and the criticism raised against his work after the terrorist attacks of 2001 in the United States, Fukuyama [15] says that he does not deny the cultural influence on political regimes but reiterates its view that liberal democracies will prevail among political regimes.

It has always been my belief that modernity has a cultural basis. Liberal democracy and free markets do not work at all times and everywhere. They work best in societies with certain values whose origins may not be entirely rational. It is not an accident that modern liberal democracy emerged first in the Christian West, since the universalism of democratic rights can be seen in many ways as a secular form of Christian universalism. […] We remain at the end of history because there is only one system that will continue to dominate world politics, that of the liberal-democratic West.

We must also include in this debate the prospect of the Marxist base that has established an opposition to Fukuyama’s view but also foresees a reduction in state authority in the future. The difference lies in the idea that, rather than economic actors acting in a free market, the abolition of private ownership of the means of production would result in the emancipation of most individuals in society. This would weaken the relationship of subservience to the state, which, subsequently, implies either a revolutionary or gradual disappearance of the modern state.

In summary, from either the right or the left, visions on the trajectory of human development are commonly skeptical about the centrality of the state or the maintenance of its power in the long run. Based on the theoretical framework and evidence gathered in this study, we suggest that political culture is a relevant and important dimension for understanding social attitudes in relation to the state.

The most prominent debate about the state that takes into consideration political culture is led by Ronald Inglehart [16] (p. 243). As he notes,

The rise of Postmodern values is bringing a move away from acceptance of both traditional authority and state authority. It reflects a declining emphasis on authority in general—regardless of whether it is legitimated by societal or state formulae. […] It reflects a systematic decline in mass support for established political institutions, and a shift of focus towards individual concerns.

In this work, we sought to verify whether these processes of social change described by Inglehart can be observed in Brazil. At the individual level, using a descriptive analysis of data from the WVS, we found that the levels of post-materialism and self-expression values indeed increase over time, particularly among young generations.

On the other hand, through descriptive analysis considering the different waves of WVS in Brazil, we could not identify the predicted trend of an increasing emphasis on individual autonomy in opposition to state authority. On the contrary, we verified an increasing average of the government responsibility variable among the younger cohort and the most recent surveys in Brazil.

In a way, this trend contradicts the prediction of Inglehart and Welzel [2], who perceive that human development follows a specific pattern and that “favorable existential conditions contribute to emerging self-expression values that give individual liberty priority over collective discipline, human diversity over group conformity, and civic autonomy over state authority”.

Based on our analysis of the Brazilian data in the WVS, it is not possible to affirm that there is an opposition between emerging post-materialist or self-expression values and priority for state authority in Brazil. Similarly, other studies addressing the postmaterialist syndrome in Brazil have also identified that an increase in post-materialists is not directly related to an increase in political participation [17,18].

We hypothesized that this unexpected emphasis on state authority is a persistent characteristic of the Brazilian political culture, which is not easily challenged by an increase in post-materialism or self-expression. Using a different data source, Almeida [10] has identified the same cultural trait, stating that Brazilians “love the State”.

However, we argue that the persistence of these values among Brazilians is mostly due to the country’s political tradition and social structure. As stated by Rayundo Faoro, there is an enduring political culture in Brazil that strengthens the subjugation of the people, especially the most vulnerable groups, in relation to the state. This perspective is partially corroborated by the data analysis conducted in this work. As we demonstrated, individual perspectives in relation to income equality are an important aspect to explain the rising level of support for the state in Brazil. Beyond that, our analysis showed that gender, education level, and the generation to which the individual belongs are relevant characteristics to explain the emphasis on state authority.

The Gramscian concept of hegemony is also a relevant theoretical contribution to understand the paradox of post-materialism and emphasis on state authority. As discussed by Castro [18], political values and attitudes, especially in Latin America, often reflect the dominant ideology that is favorable to maintenance of the status quo. Also, as stated by Böhm, Dinerstein and Spicer [19], autonomy is embedded in specific social, economic, and cultural context, and cannot be analyzed out of this scope. Therefore, the very opposition between civic autonomy and state authority cannot be taken as universal and must be questioned in specific contexts.

Finally, the empirical evidence presented here, in association with the literature, does not deny the main findings of Inglehart and Welzel regarding human development. What the results of this work challenges, instead, is the view that every human society follows the same path, including similar social processes, as predicted by their theory. In fact, political culture might play an even more enduring and complex role in value change, as the Brazilian case demonstrates for the specific issue of social support for the state authority.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/8/2/20/s1.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by CAPES/MEC.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, G.A.; Verba, S. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, H. A Culturalist Theory of Political Change. In Culture and Politics: A Reader; Crothers, L., Lockhart, C., Eds.; St. Martins: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 789–804. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1971, 65, 991–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitter, P. Neo-corporatism and the State. In The Political Economy of Corporatism; Grant, W., Ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, E. A consistência das medidas de pós-materialismo: testando a validade dos índices propostos por R. Inglehart no contexto brasileiro. Sociedade e Estado 2007, 22, 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faoro, R. Os Donos Do Poder: Formação Do Patronato Político Brasileiro, 3a. ed.; Editora Globo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, F.H. Pensadores Que Inventaram o Brasil; Companhia das Letras: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.C. A Cabeça Do Brasileiro; Editora Record: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Capistrano, D. Um retrato dos brasileiros. Soc. E Cult. 2008, 11, 393–395. [Google Scholar]

- Avritzer, L.; Navarro, Z.; Marquetti, A. A Inovação Democrática no Brasil: O Orçamento Participativo; Cortez Editora: São Paulo, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Borba, J.; Ribeiro, E.A. Orçamento Participativo e cultura política: Explorando as relações entre inovação institucional, valores e atitudes políticas. Política Soc. 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, S.P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order; Free Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. History Is Still Going Our Way. In The Wall Street Journal; Dow Jones & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. Postmodernization Erodes Respect for Authority, But Increases Support for Democracy. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Norris, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, E.A. Pós-materialismo e participação política no Brasil. Soc. E Cult. 2008, 11, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castro, H.C.O. Cultura Política, Democracia e Hegemonia na América Latina. Rev. Estud. E Pesqui. Sobre Am. 2011, 5, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, S.; Dinerstein, A.C.; Spicer, A. (Im)possibilities of Autonomy: Social Movements in and beyond Capital, the State and Development. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2010, 9, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The groups were created based on the variable X002 (year of birth). The values for the wave of 1991 were inputted given the absence of values for this variable in the original file. The rationale for creating and comparing pseudo-cohorts in cross-sectional surveys is explored in Deaton (1985). |

| 2 | Based on the National Household Survey (PNAD/IBGE) data, figures elaborated by IPEA. |

| 3 | Cases with the values 8, 9 and 10 in the GovResp scale. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).