Abstract

Much of the research on contemporary youth in Western societies has shown that transitions to adulthood are being postponed, protracted, and becoming more complex (i.e., less likely to follow a predictable and “orderly” sequence as in earlier generations). Extended schooling periods, changes in the labor market and challenges to obtaining autonomous housing are some of the top drivers for such change. Demographers interpret such developments as a sign of a second demographic transition, whereas sociologists stress that they are a consequence of the broader process of social individualization, by which individuals are assuming an increasingly central role in the organization of their lives. While in younger cohorts the evidence base is strong concerning transitions to adulthood, in some national contexts comparisons with the past rely on impressionistic accounts or to easily assume that some social, economic, and cultural factors were present. Drawing on data from the “Family Trajectories and Social Networks: The life course in an intergenerational perspective” research project, this paper re-examines the transitions to adulthood of three Portuguese cohorts (born in 1935–1940, 1950–1955 and 1970–1975), namely in what concerns their timing, duration, and sequence. This is achieved by looking at their life-calendars across different domains (namely family and intimate relations, school, and work). Analysis of the results allows us to discuss critically to what extent current transitions to adulthood are different and to assess cohort heterogeneity according to class and gender. Additionally, it enables us to frame discussions on generational and structural change more adequately in Portugal.

1. Introduction

Over recent decades, the transition to adulthood has become a thriving area of research in sociology and other social sciences [1,2]. While its popularity in Europe is mostly related to the recent evolution and heterogeneity within this geopolitical context, American scholars have long been paying attention to factors influencing the timing and order of transitional events [3,4,5,6,7,8].

The transition to adulthood is perceived as a critical period in life. It is an eventful life stage during which many transitions occur and overlap. In an era when formal rites of passage have all but been abolished, at least from western societies, this is a rather intense period, as most individuals experience new roles and take greater responsibilities [9]. Lay assertions tell us that transitions to adulthood are being postponed and that transitional periods are being extended for younger cohorts. While this is confirmed by empirical data from demographic or cross-sectional surveys, such data is often lacking when it comes to asserting the heterogeneity within age cohorts.

In this paper, we analyze how transitions to adulthood have evolved in Portugal over the last decades. Our key research questions are: what are the main differences, in terms of class and gender, in the timing, calendar, sequence and duration of transitions? Have these differences increased or decreased in recent cohorts? To answer these questions, we establish a comparison between cohorts, aiming to find (dis) similarities and tendencies, which we relate to generational constraints and opportunity structures. Additionally, we discuss how gender and class frame different transitional models within each cohort. Our discussion is embedded in theoretical debates about whether (and to what extent) transitions are being postponed, protracted and becoming less predictable.

1.1. Towards a Critique Reading of Calendars, Norms and Social Roles

The timing and order of events in the transition to adulthood are key research issues for life course sociologists and other researchers [10,11]. For some time, the literature mostly addressed the occurrence of events and aimed to identify typical calendars. Later, more attention was geared to the order of events [3,6,12]. Some researchers assumed that transitions typically follow a specific sequence (namely: school-work-marriage) and discussed their findings classifying them as normative vs. non-normative [3] or consistent vs. inconsistent [6]. From this point of view, the transition to adulthood is a process that is over when individuals have completed a given number of events, with the transition to parenthood being the conclusive event [2]. A major limitation of this approach is that it takes a schematic look at the transition to adulthood, often reducing it to a checklist. Critics have rightfully pointed out that such approaches reverberate with media and academic discourses that have been bullying a new generation of youths who have not completed the checklist, tagging them with derogatory monikers [13].

Furthermore, approaches relying on the analysis of chronologies are often lacking in what concerns how “norms” are constructed, apprehended, and maintained, and how they vary according to class, gender, or ethnicity [7,14]. In fact, on the theoretical level, the linkage between norms and social regularities remains controversial. American researchers commonly stress the significance of informal age norms, while European researchers tend to emphasize institutional (and State) regulation over age norms [15,16]. Consequently, authors coming from the American tradition are usually more attentive to norm disruption, either in the sequence or in the timing of transitions, because they assume it can lead to negative consequences later in life [3,17], which entails a strict reading of the principle of lifelong development within life course sociology. Some even argue that “successful” transitions depend from adhering to the socially and institutionally imposed calendar because the very structure of institutions is designed according to these standards, thus rewarding normative compliance while penalizing deviation [18]. These claims have been criticized on theoretical and methodological grounds. Often, what is credited to social norms is, to a large extent, an outcome of structural and institutional processes that lead to a high degree of population homogeneity [16,19]. Other authors criticize the claim that normative linearity relates with positive outcomes, while others question the assertion that disorder in the transition to adulthood is something new [6,13,20,21].

By adopting a life course perspective, we need to consider that the linkage between age and social roles is a socially and culturally regulated process, which is historically contingent. The transition to adulthood is regulated by several institutions (school, the labor market, family, etc.) and by sociocultural expectations concerning the roles individuals should adopt. These expectations are even made clear by the list of transitions (and their very order) that researchers usually account for: leaving school; start of working life; residential autonomy; family formation; parenthood [2]. This is because, in western societies, adulthood has been synonymous with economic independence and the ability to set up a procreative nuclear family. Therefore, this choice of events conveys a deep symbolic interweaving between expectations of family (biological, generational) reproduction and social reproduction (institutional, economic, and cultural).

The organization of transitions to adult life according to a school-work-family model, as observed in western countries during the third quarter of the twentieth century, resulted from several processes unleashed in the first modernity. As economic rationality expanded to the way human lives are organized, they became more predictable and secure [22]. In fact, age stratification systems, such as those imposing a minimum legal age to marry, to enter and leave school, to perform military duty, or to start working, made transitions to adulthood more predictable, orderly, and linear. In fact, comparisons between different periods and geographical contexts have shown that the school-work-family model is historically and culturally variable. Still, some authors have stressed the need to investigate the coexistence of different models within a society or generation [23]. Such is necessary to develop a more nuanced view on social generations, which is not pinned on a specific model of biographical trajectory or pattern of transition to adulthood.

1.2. Recent Trends and the Portuguese Case

To frame the Portuguese case, we now take stock of recent research on the transition to adulthood in Europe. At the height of organized modernity (roughly defined as the period between 1950 and 1970), demographic transitions were early, contracted, and simple [1]. Family transitions (residential autonomy, conjugality, and parenthood) were strongly associated with specific ages and occurred sequentially [24]. Since the mid-1970s a new pattern of late, protracted, and complex transitions to adulthood emerged, under the combined effect of transformations in the labor market, longer schooling periods and significant cultural change [1].

Transitions are also becoming increasingly reversible [25], namely because the labor market is more unstable with the proliferation of flexible employment modalities, underemployment and unemployment, circumstances that pave the way for the so-called “yo-yo” trajectories [9]. In any case, a detailed look at transitions to adulthood that took place during the 1960s, using some of the theoretical-methodological devices of contemporary sociology, showed that they were not as straightforward as anticipated; in fact, complexity existed in similar doses to those found for contemporary generations of youths [20,21].

Research on transitions to adulthood in contemporary Europe has found consistent trends, namely a general postponement of events that suggests that the transitional period between adolescence and adulthood are being extended [26,27]. However, despite this convergent trend, substantial heterogeneity persists [1,28], especially between the ages of 20 and 35 years old [2]. Moreover, even though postponement occurs both among men and women, a strong gender bias continues, with women generally completing most transitions earlier than men [2,28]. Postponement of transitions is generally credited to the extension of education [2], while heterogeneity within Europe is usually related to cultural, institutional, and economic differences.

Culturalist explanations pin differences within Europe on contrasting values on individual autonomy, conjugality, and parenting [29,30]. Others stress the role of institutional designs and specifically welfare state typologies [31]. Furthermore, other authors point out that social inequalities are also a shaping factor, namely asymmetries in access to the labor market [30,32]. To be sure, the link between school and labor market receives a sizeable share of the literature focusing transitions to adulthood [32,33,34,35]. On top of being a highly regulated transition (e.g., formal norms concerning compulsory education, legal working age, etc.), young adults’ financial independence and residential autonomation depends on achieving on it to a large extent [36]. Entering the labor market is defined as a fundamental step for all the transformations involved in the transition to adult life [37]. Recent research shows that this transition has long-lasting effects on the life course, also emphasized that vocational systems facilitate labor market integration and that action welfare states can attenuate or exacerbate generational differences [33].

In international comparisons, Portugal is usually framed within the cluster of Southern European countries. These societies are describes as having: high levels of social inequality; frail and underdeveloped welfare states; and strong familial values rooted in their Catholic or orthodox heritage [38]. In this context, transitions to adulthood are especially unstable in the school-to-work node, as youths experience long periods of inactivity, unemployment, and job precariousness [32,34]. Since welfare state policies for housing are fragile or even absent, residential autonomy is highly reliant on employment status and income level [13,39]. Later residential autonomy results in later family formation patterns [40]. Despite being described as a novelty, such patterns resonate with strategies observed in peasant societies for coping with resource shortage or inheritance, through celibacy or multifamily co-residence [41].

Regardless, research also shows that changes to the transitions to adulthood “do not entail (…) a change in the chronology of (…) the main thresholds: (…) actually, the same sequence still prevails in Europe 1” [36]. A peculiar feature of transitions in Portugal is the linear sequence between residential autonomy from parental home, the start of a conjugal relationship and having a child; in other words, the time to “experiment” after leaving the parental home is for most a short period [36]. Other researchers point out that a highly standardized life cycle, close to an archetypal view of a linear and predictable life course, is still idealized both in the Portuguese and European contexts [36,42,43].

Qualitative accounts have stressed the plurality of transitional patterns in contemporary Portugal [37]. Precarious transitions are prominent among disadvantaged social groups where unstable links with the labor market prevail, a situation worsened under the conditions of post-Fordist capitalism. In other cases, a combination of lower expectations concerning education, early entrances in the labor market, and a high level of social and familial control, compel young people to early transitions [44]. For highly qualified youths, delayed or double-phased transitions (work first, family later) are a common outcome of the combination of safer labor market integration and high levels of career investment. Gradual transitions are typical of individuals that constantly adapt their personal projects, striking some type of balance between family and work. Although they follow the same linear sequence, transitions are longer, because of labor market precariousness. Experimental or ludic transitions are experience by a few more leisure-oriented and hedonistic individuals.

Economic cycles and unique historical events also interfere with life calendars, shape individuals’ perspectives on the life course and frame social representations [7,17]. In Portugal, the Revolution of 25 April 1974 and the social transformations that followed significantly impacted transitions to adulthood. Likewise, the authoritarian Estado Novo regime and its brand of conservatism, which held power for half a century, created an enduring effect. However, the effects of major social events are not equally felt by all members of a given society; they depend on age, as well as on personal, social, and familial circumstances at the time. If we hastily link age cohorts to specific patterns of transition to adulthood, we inadvertently conceal their heterogeneity, which makes it difficult to understand the relationship between social inequality and historical time. Studying the variability of transitions to adulthood within cohorts enables us to simultaneousness consider the interplay between social stratification, social structure, and demography [7]. However, the interrelatedness between changes to the structure of the life course and social inequalities has of yet not been subjected to detailed empirical analysis, rendering the issue ripe for further enquiry [18].

Over the last four decades, Portugal went through an intense process of social, political, and institutional change that unquestionably transformed transitions to adulthood; that is easily attested just by checking data on university enrolment, average age at marriage or first child [45]. Our main hypothesis points to a general postponement of transitions stemming from our theoretical framework and from the available empirical data. Another hypothesis is of a (moderate) extension of the transitional period among younger cohorts, in comparison with cohorts that faced limited to schooling and that were brought up in a context that consented child labor. More broadly, we hypothesize that social inequalities, namely those relating to gender and class, are on full display during the transition to adulthood.

While conveying a strong message to both lay assertions and sociological accounts, demographic or cross-sectional survey data do not properly account for the heterogeneity within a given age group. During adolescence and young adulthood, individuals negotiate their way through school and the labor market, institutions themselves pervaded by social inequality. Therefore, we are likely to find differences in the timing, calendar, and sequence of transitions according to class and gender [1,13,46]. Nonetheless, since women have a high level of participation in the labor market and equal or surpass men in academic achievement, we anticipate an attenuation of gender differences on the timing of school to work transitions.

2. Materials and Methods

Data

Our analysis relies on data collected during 2010 for the Portuguese “Family Trajectories and Social Networks: The life course from an intergenerational perspective”. This research project included a survey to a representative sample of 1500 male and female individuals belonging to three different cohorts (born between 1935–1940, 1950–1955 and 1970–1975)2. The research project aimed to relate biographical time with historical and social time, by comparing the life trajectories of men and women born in three age cohorts. An additional aim was to test the hypotheses of pluralization and de-standardization of the life course. Therefore, cohorts were selected by their specific social, historical, and institutional frameworks. The cohort of those born between 1935 and 1940 had their formative experiences in the dictatorial, politically repressive, and socially conservative context of the Estado Novo. The cohort of those born between 1950 and 1955 was still brought up during the Estado Novo experienced the enormous social and political transformations that followed the Revolution of April of 1974 in their early adulthood. The cohort of 1970–1975 incorporates individuals who already were brought up under democracy and that entered adulthood around the time Portugal’s joined the EEC/EU.

Key Dimensions and Concepts

Since the mid-1970s, quantitative research on the transition to adulthood has relied on a given number of age markers, such as leaving school, starting work, achieving residential autonomy, starting a cohabiting relationship, and becoming a parent [2,7,24,47]. Their timing, prevalence, and sequence are some of the indicators most often used in research on transitions. While the timing of each transition allows us to create an approximation to the chronology of events, its prevalence is important to determine how often a transition occurs in a given population. Sequences are important because they allow us to infer on the normative order of events and its changing face [2].

Even though most analyses of the timing of events depend on measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode), relying exclusively on them is theoretically insufficient, as they dilute the diversity within a group and do not consider non-events [13]. In fact, non-occurrences are a common problem that skews down data and equalizes individuals. As an alternative, some researchers propose looking at dispersion statistics (standard deviation and interquartile range) to overcome this issue [48].

As intra-cohort diversity relates to processes of accumulation of advantages/disadvantages, life course analysis benefits from going beyond central tendency measures. Additionally, the prevalence of events is best understood if measured at different stages (25, 30 and 35 years of age), a strategy that enables us to identify changes to the cadence of transitions.

Concerning the order of events (and non-events), the number of possible permutations is massive3. A holistic approach would entail resorting to Sequence Analysis [49,50]. However, since the main objective of this paper is to address cohort (dis)similarities in what concerns the timing and transitional order of events, we opted for a parsimonious and tested approach that resorts to a set of pertinent indexes (Table 1) [51].

Table 1.

Indexes of change to normative transitional order *.

3. Results

3.1. Transition Calendars: Converging and Diverging Trends

The mean age at the five transitional markers suggests that a sequential model persists (Table 2). When comparing cohorts, results show that data public transitions (leaving school and starting work) occur later in recent cohorts, while private transitions (entering a cohabiting relationship and becoming a parental) have a V-shaped evolution (contracting from first to the second cohort, increasing from the second to the third cohort). The mean age at leaving the parental home occurs at roughly the same age, regardless of the cohort. However, if we consider dispersion measures, a more nuanced picture emerges. Additionally, that also enables us to clearly show how institutional regulation, on the long run, shapes the timing of transitions. A clear example concerns the extension of mandatory schooling, which drives up the mean age when leaving school. Furthermore, the widening interquartile range for those born in the early 1970s clearly highlights a pluralization of school trajectories. Also, the evolution of the when individuals started working is exemplary of institutional change, namely regulation of the minimum age to work4.

Table 2.

Mean age at transitions and dispersion measures per cohort.

Concerning the age when individuals left their parental home, dispersion measures show a high level of heterogeneity in all cohorts. In the 1950–1955 cohort ages at first cohabitation and at first child are closer to the mean, which supports the hypothesis that these individuals experienced a stronger normative institutional setting. This is true both for both genders. In addition, in fact, there are relevant developments between cohorts relating to gender (Table 3). From cohort to cohort, the age when individuals left school and started to work increase regardless of gender and the gap between men and women is tapered. On the other hand, the difference between men and women in the age at leaving parental home remains stable (roughly 1.5 years earlier for men).

Table 3.

Mean age at transitions per gender *.

The interval between the age when individuals started to work and left their parental home contracted between these cohorts, which enables us to dispute the much-heralded notion that, in the past, achieving residential autonomy soon followed starting to work [36]. Data shows that these events were, for the most part, unlikely to be synchronized. Such a model is more likely to have existed in central/northern European societies that had robust educational systems, which worked in coordination with regulated labor markets. Nevertheless, such assertions have also been disputed in those contexts, as recent readings of data from the 1960s show a high level of complexity and uncertainty in transitions to the labor market [21].

Due to the acute lack of resources, infrastructures, and institutional incentives to go beyond basic education, most individuals born in the late 1930s and early 1950s started working at a very young age and only left their parental home much later. Only for those who were born during the early 1970s did the gap between work and residential autonomy narrowed. For those born in the early 1950s, the mean age at leaving their parental home and at the start of the first cohabitation are close, suggesting that, for many, these transitions occurred in quick succession. In the older cohort, the interval between these two events was larger, especially for men, while in younger cohort the gap widens for both genders, which suggest a higher desynchronization between leaving parental home and starting cohabitation. According to Nico (2011), in younger Portuguese cohorts, individuals that leave their parental home at a later age are precisely those who do not do it to start cohabiting. It is worth mentioning that the interval between the age at the start of the first cohabitation and the age when individuals became parents widens. While among men, this gap increased from cohort to cohort, for women it diminished for those born in the second cohort and increased for those born in the third cohort.

Class origins have a structuring effect over transitional calendars (social classes were operationalized according to the ACM class typology [53,54]) For example, among those born during the late 1930s, class differences were very sharp concerning the age when they left school and the age when they started working. Although school careers were, as a rule, short and work started at a rather young age, there was a sharp contrast between individuals whose parents were Professionals and Managers and those from a working-class background (Industrial Workers or Routine Employees). That was still the case for those born in the early 1950s. Only among those that entered school after the 1974 Revolution can we say that class differences are somewhat attenuated, which is an effect of the democratization. Still, class origin differentials remained substantial.

Overall, the combined evolution of events shows a convergent trend from the first to the second cohort and a divergent trend from the second to the third cohort (Table 4). For example, there is a high level of normative uniformity regardless of class origins among those born in the early 1950s, especially in what concerns “private/familial transitions” (starting cohabitation and becoming a parent). Conversely, the trend is reversed for those born in the early 1970s, namely as familial transitions occur at increasingly different ages for those whose class origins are among Professionals and Managers and Industrial Workers (a gap of roughly 3 years).

Table 4.

Transitions—means per class origin *.

3.2. The Duration of Transitional Calendars

If we look at the range between the mean age at the first and at the last of the aforementioned five transitional events, data suggests a shorter transition calendar among younger cohorts. However, while tempting, considering the duration of transitional calendars as merely the range between mean ages at the first and last transition incurs in a “sequencing fallacy” [55]. In fact, such an approach compares different subsets of individuals who have gone through an uneven number of transitions. As shown in the following subsection, in all cohorts a proportion of individuals did not experience one or more transitions. Therefore, an effective measurement of the duration of transitional calendars entails comparing the aggregated individual duration of transitional periods among those who experienced most transitions (we consider the duration of those we completed 4 or 5 out of 5). Only by doing so can we test if the assertion that the transitional period is being protracted holds.

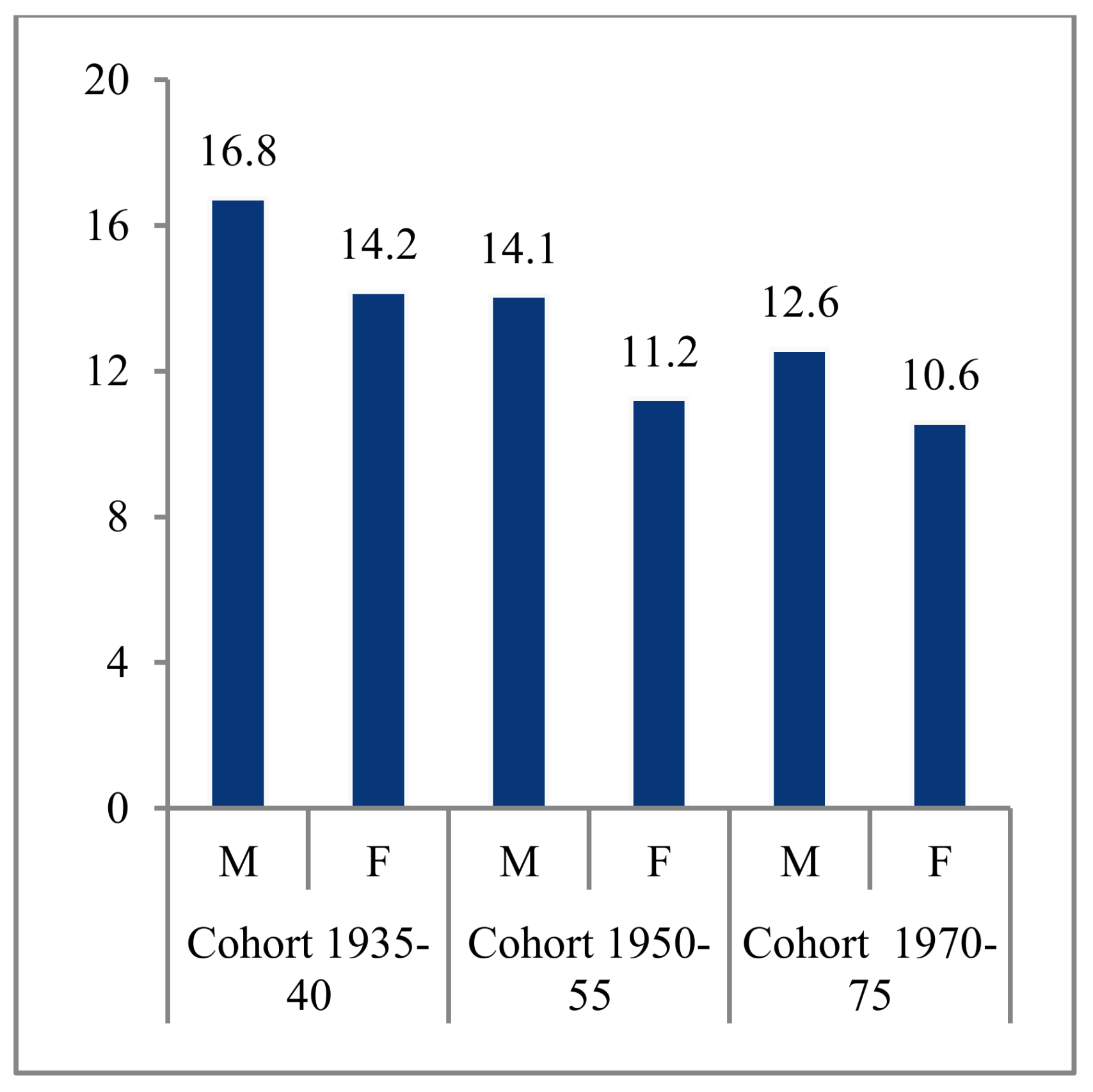

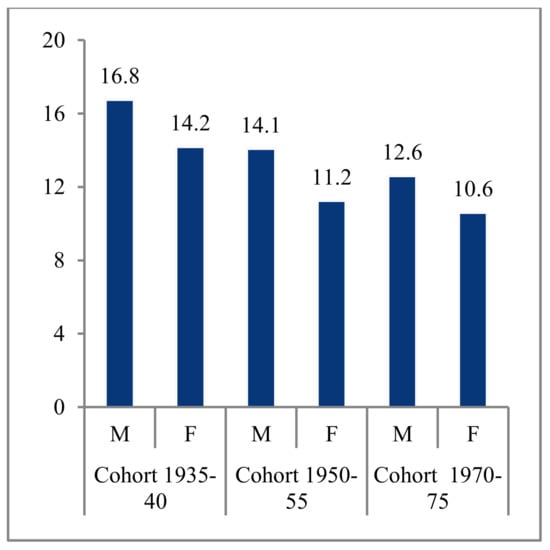

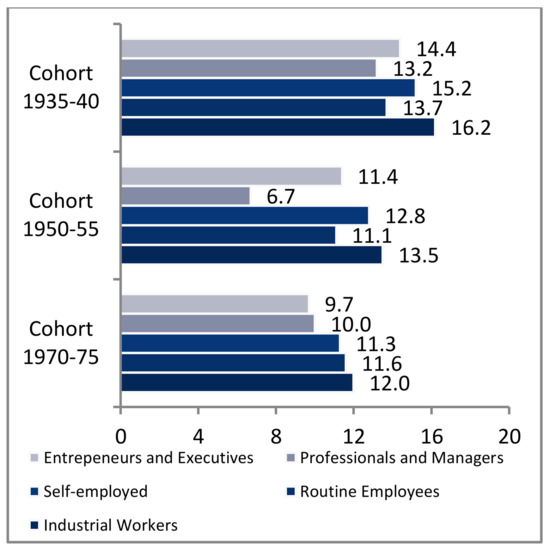

There are noticeable differences in the duration of transitional periods according to cohort, gender, and class origin (Figure 1 and Figure 2). On the other hand, in more recent cohorts, transitional periods are in fact shorter, something that clearly contradicts some commonly held views on contemporary life courses. The duration of transitional periods remains gendered, with women experiencing transitional events at a faster pace than men.

Figure 1.

Range between first and last transition for those who experienced at least 4 transitions up to 35 years of age, by cohort and gender.

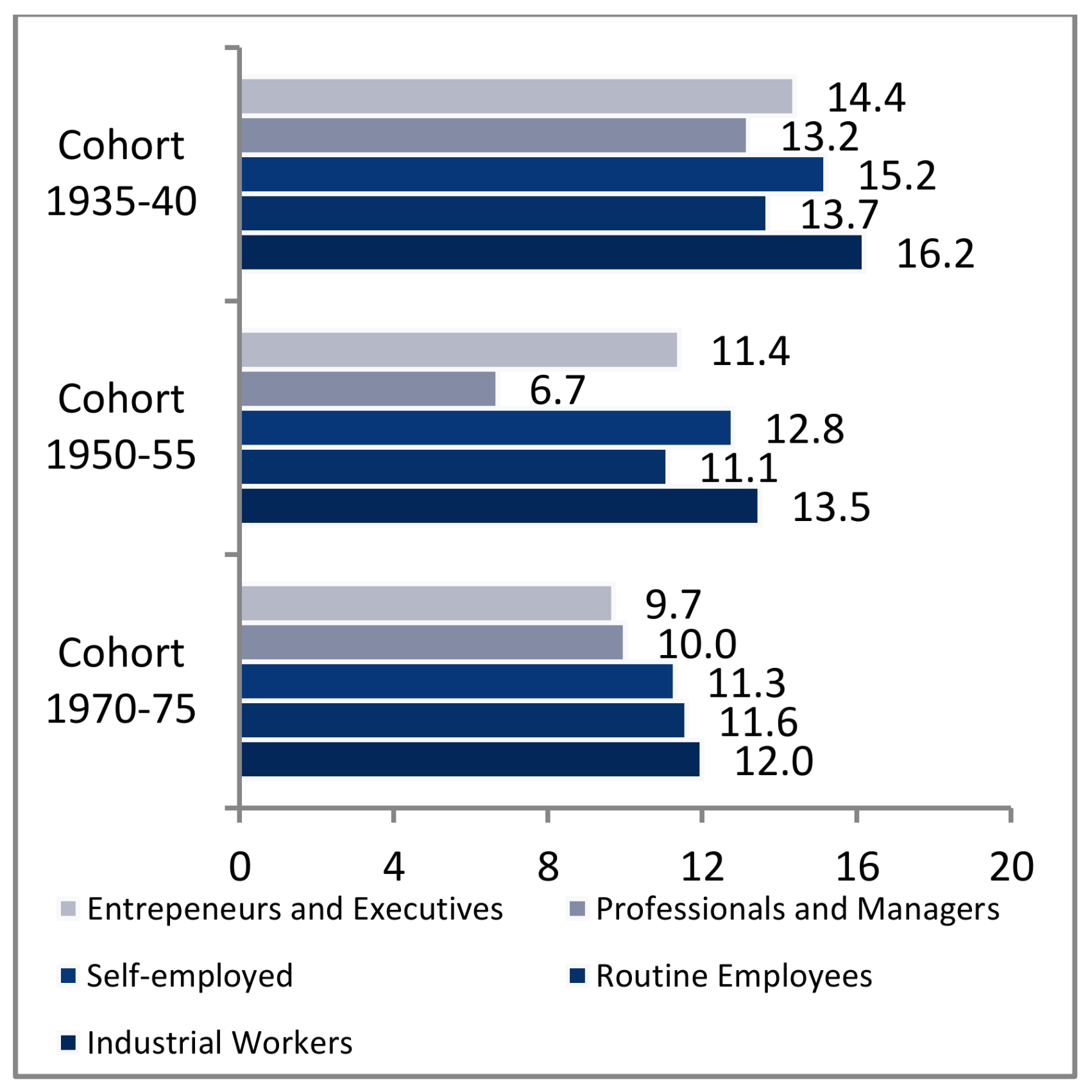

Figure 2.

Range between first and last transition for those who experienced at least 4 transitions up to 35 years of age, by cohort and class origin.

Concerning social class origins, for those born during the late 1930s, the duration of transitional periods was longer for those whose parents were Industrial Workers, Independent Workers and Entrepreneurs and Executives. In the second cohort, the ranges between the first and last transition are overall significantly shorter, especially for those from Professional and Managerial origins. Among those born during the early 1970s, durations are lengthier, especially for individuals from a working-class background (Industrial Workers and Routine Employees).

3.3. Prevalence of Transitions: from Anticipation to Postponement

In this section, we look at the proportion of individuals that completed each transition at three age thresholds (25, 30 and 35 years of age) (Table 5)5. As expected, we find greater variability according to gender and cohort concerning the proportion of individuals who completed secondary education. Against the backdrop of the Estado Novo regime and its distrustful and elitist outlook on education [56,57], it is hardly surprising to find such a low proportion of men and women who completed secondary education in both the 1935–1940 cohort (8.5% and 4.6%) and the 1950–1955 cohort (22.1% and 17.2%). Among those born in the early 1970s there is a remarkable increase and the gender imbalance is reversed.

Table 5.

Percentage of individuals that completed a transition at three age thresholds.

In Portugal, the formal labor market has been highly feminized since the 1960s [58]. That distinctive feature within Europe is clearly shown in our data. In all cohorts, a high proportion of women had already engaged in work at 25 years of age. Nevertheless, for women born during the late 1930s and early 1950s, a number of issues, namely employment precariousness, unemployment, staring a conjugal relationship or becoming a parent, would lead to employment trajectories often very different from men [59].

If we consider the 25-year threshold, achieving residential autonomy was a highly gendered endeavor, especially for the first and third cohort. Although differences are narrower for those born in early 1950, overall men tended to leave their parental homes later and at a slower pace than women. Among those born in the early 1970s, the gender gap widens with women more likely to be autonomous alt the 30 and 35-year thresholds.

Data on the age of first of cohabitation is somewhat similar, as we also found a higher proportion of individuals with residential autonomy when they were 25 years old. However, there is a significant decrease in the proportion of individuals, namely men, who started cohabitating by their thirtieth or their thirty-fifth year. This should, however, not be merely regarded as a postponement of statutory transitions; it is also a clear indicator that contemporary models of solo living during early adulthood are increasingly common in Portugal [60,61].

While most individuals born in the late 1930s entered parenthood during their life course, becoming a parent before 25 years of age was more common for women than for men (59.7% vs. 37.2%). Both trends intensified for those born in the early 1950s (gender imbalance and becoming a parent before their 25th birthday). Conversely, both trends are reversed among those born in the younger cohort; becoming a parent before 25 years of age was rare for men (18.4% vs. 43.3%). At 30 years of age, this transition was completed by nearly half of the men and two-thirds of women. More than one-fifth of men born in the early 1970s were childless at the 35-year threshold, a substantially higher proportion than in the other two cohorts.

The prevalence of transitions according to social class origins provides important elements to understand how transitions to adulthood have evolved in Portugal (Table 6)6. While overall very low, the proportions of completion of secondary education in the first and second cohorts reflect almost exclusively the logic of social class reproduction, among the more qualified strata of the population. Conversely, among those born the early 1970s, there is a degree of educational mobility for those from subaltern positions in the class structure.

Table 6.

Percentage of individuals that completed a transition at 30 years of age by social class origin.

Data on residential autonomy is very homogenous for the first and second cohorts and less so for the third cohort, with offspring of Entrepreneurs and Executives tending to stay longer in their parental home. Data show that while there is a general decrease in proportion of those who on start a cohabitation and becoming a parent before 30 years of age, the trend is much stronger among those from Entrepreneurial and Professional social class backgrounds.

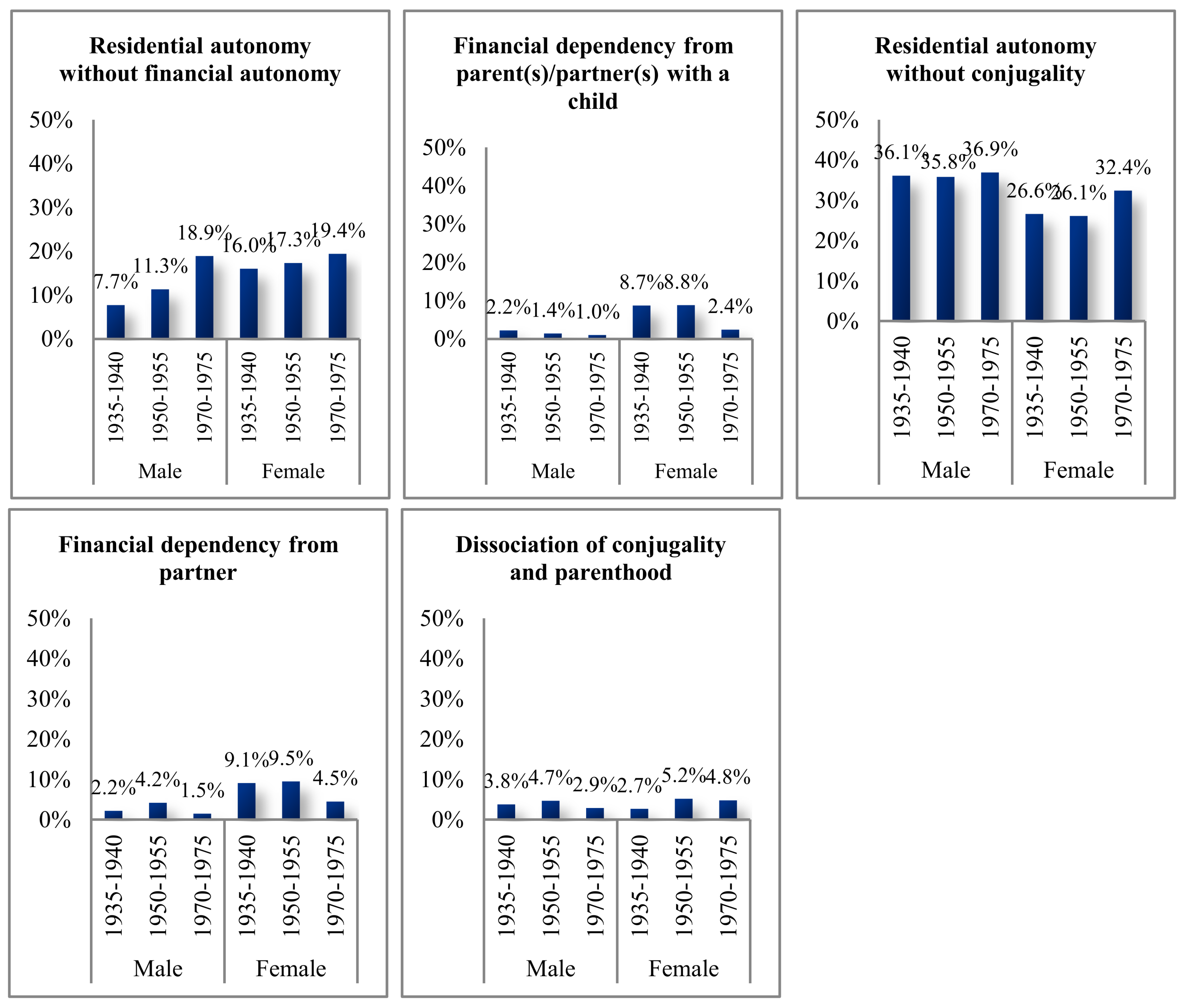

3.4. Changes to the “Normative” Transitional Order

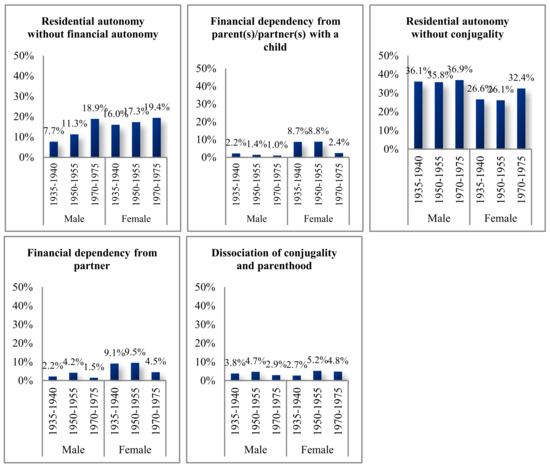

In order to find changes to the “expected” (or normative) order of events, we look at four indices (Figure 3). When comparing cohorts, leaving the parental home without entering the labor market is the change that most significantly increased (12.6%, 14.9% and 19.2%). This is always more common among women than men, but the proportion of men increased in more recent cohorts. As for residential autonomy before conjugality, data show similar values for the first two cohorts (around 30%), with a slight increase in the younger cohort (34.1%). Leaving parents’ home before starting cohabiting is more common for men than women, although differences subsided for those born in the early 1970s.

Figure 3.

Changes to the normative order of transitions by sex and cohort.

Overall, these trends might suggest a pattern of family formation patterns and gender roles along the lines of a “male breadwinner-female homemaker model”; however, the gender-convergent tendency is mostly related to enrolment in higher education, which has increased substantially since the 1990s. For many Portuguese students, entering university often involves moving away [62].

Additionally, data reveals that starting cohabitation is unlikely to precede entering the labor market, regardless of cohort. That sequence of events, which entails financial dependence from a partner, existed for a minority of women from the first two cohorts, but is residual in the 1970–1975 cohort. Becoming a parent before entering the labor market evolves along the same lines, as having children and being dependent of a partner was a condition that some women born in the late 1930s and early 1950s faced but that was unlikely for those born in the early 1970s. However, we must keep in mind that joining the labor market is a highly reversible transition, either by choice or due to external factors, such as unemployment. Finally, we find that becoming a parent prior to starting a cohabiting relationship is a rare event, for both men and women from the three cohorts.

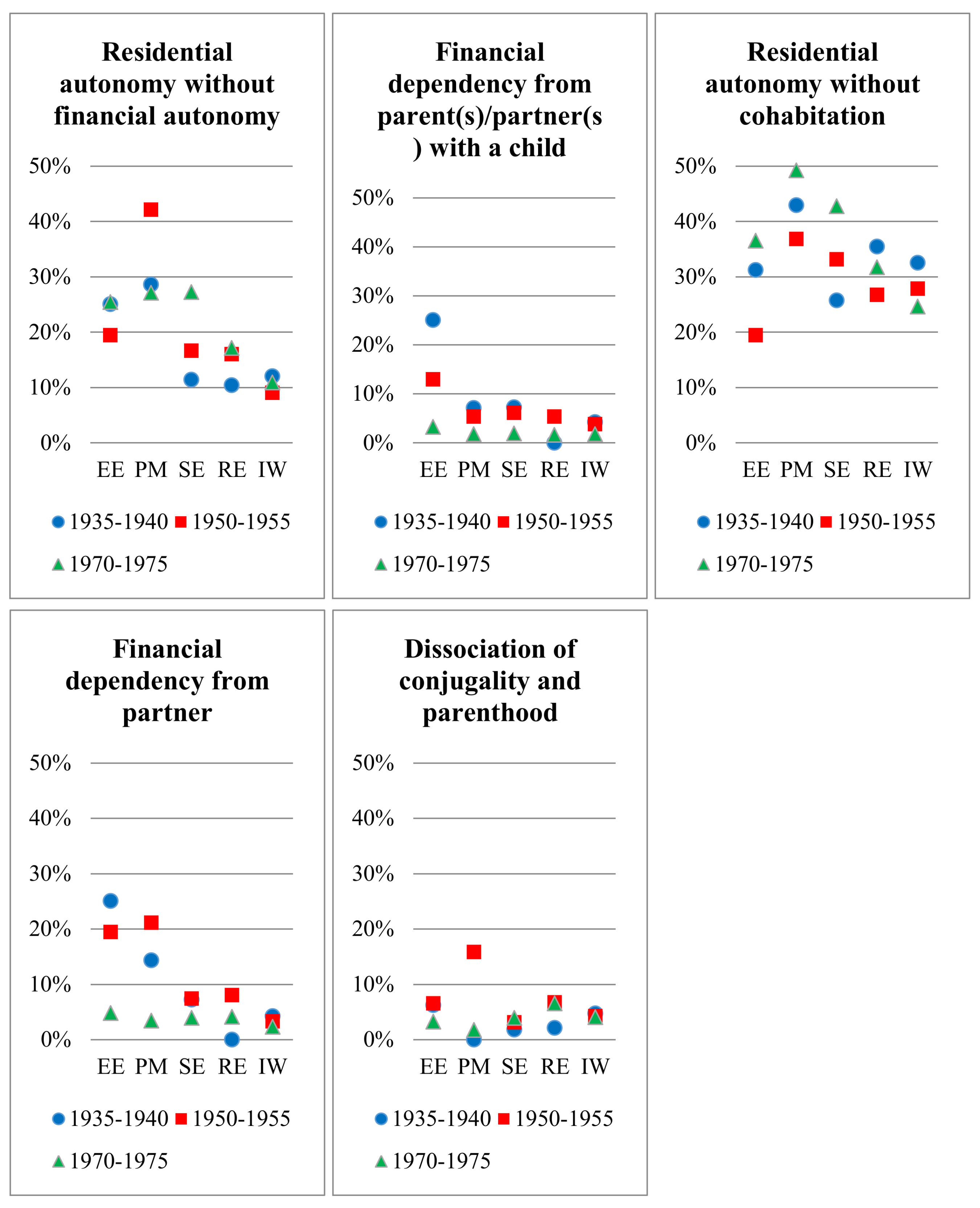

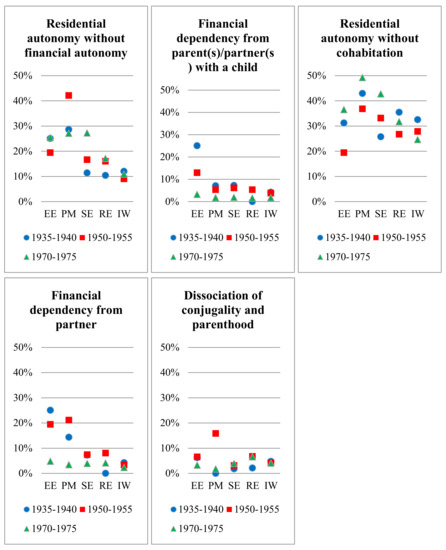

Looking at these indexes according to social class backgrounds provides additional elements to our understanding of how transitional normativity relates to the social structure in Portugal (Figure 4). While financial dependency from a partner was common for some born during the late 1930s and early 1950s, this was highly dependent on social class: it was uncommon among those whose parents where Self-employed, Routine Employees and Industrial Workers. An almost identical case can be made concerning becoming a parent prior to start working, which was only common between those from an Entrepreneurial and Executive background. Class differences concerning these two changes to the normative order are not relevant for those born during the early 1970s.

Figure 4.

Changes to the normative order of transitions by sex and cohort.

Conversely, attaining residential autonomy without financial autonomy is highly dependent on individual’s social class background; when parental economic and cultural resources are higher it is more likely that individuals leave their parental home before finding a job. Since this change to the normative sequence is often related to long educational trajectories, in the younger it is one of the aspects the most contrasting experiences between individuals from different class backgrounds.

While leaving parental home prior to starting cohabiting is overall a more common event, its incidence varies according to a similar social class gradient. It is more likely to have been experienced by individuals from Professional and Managerial backgrounds, regardless of the cohort. Among those born in the early 1970s, this index increases for individuals from all social origins except for descendants of Industrial Workers, rendering it one of the most differentiating differences in terms of social background.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we analyzed how transitions to adulthood in Portugal evolved over the last decades. Our aim was twofold: firstly, to identify differences, in terms of class and gender, in the timing, calendar, sequence and duration of transitions; secondly, to assert if these differences have increased or decreased in recent cohorts. Drawing on the literature, we tested a number of hypotheses, namely that transitions are overall being postponed, taking longer and less likely to follow a predetermined sequence than they did in central European societies after the Second World War. Additionally, we suggested that this transitional period is likely to remain highly differentiated along gender and social class lines.

A first conclusion is that most events associated with the transition to adulthood are in fact being postponed, i.e., they occur at a later age in more recent cohorts. However, we should carefully read the different evolution of the timing of public transitions (leaving/finishing school, entering the labor market) and private or familial transitions (starting cohabitation, becoming a parent). Cohort comparisons showed that a two-stroke transition prevailed for those born during the late 1930s, i.e., a long interval between two sets of events. Data suggests that, for older cohorts, transitions into adulthood anchored more on entering cohabitation/conjugality than starting to work, which for most happened at a very young age. Only after a fairly long period of work, during which economic resources and conditions were accumulated, could individuals afford to achieve other transitions. Even though this two-stroke pattern of transition into adulthood persisted for those born during the 1950s intervals were shorter, as schooling periods were slightly extended, and private transitions tended to occur earlier. Conversely, many of those born during the early 1970s did in fact postpone their private/family transitions and a few men left their procreative trajectories open-ended [63,64]. With the overall extension of schooling periods and later entries into the labor market, most individuals in the younger cohort experienced all the major transitional events within a shorter time span.

Therefore, our research strategy, which relied on both between-cohort and intra-cohort comparisons, allow us to simultaneously conclude that events tend to occur later in more recent cohorts, while transitional periods are being compressed and not necessarily protracted. In fact, the compression of the transitional period, an idea that is counterintuitive and that goes against lay assertions of contemporary youth, was observed across Europe [13,46]. Furthermore, analyses of contemporary transitions often overlook the structural and institutional conditions that pinned transitions to adulthood of more distant generations. A certain “fetishism of the present” [20,21], which is overly attentive to the present-day minutiae, and the tendency to paint the past with too broad a brush leads to oversimplifications such as those that posit that youth is being extended in recent cohorts in comparison with the past [13]. In fact, what is distinctive of recent cohorts is the sheer density of events during the third decade of life.

A second conclusion highlights how institutional change impacts transitions to adulthood. The authoritarian and conservative ideology of the Estado Novo regime was ingrained in all institutions that framed everyday life [65]. The pillars of this model of society were: work (promoted from an early age); nuclear procreative family; and traditional gender roles. Education beyond the basic skills of reading, writing, and counting was not fostered, at least for the masses. The effects of this model in transitions were strongly felt by those born in the early 1950s. Additionally, for older cohorts, institutional regulations strongly permeated intimate life and fostered private transitions to follow hegemonic mores more rigidly, namely in what concern family formation.

The Revolution of April 1974 has a transformative effect on many fields of social life. Education radically changed, through the extension of mandatory schooling, expansion of school infrastructure and by the subsequent expansion of higher education. This allowed for a widespread, and unparalleled in the past, access to education for younger cohorts. Enrolment in education was also reinforced by legal changes that set the minimum age to work at a later age, which explains for a greater degree of homogeneity in the calendars of public transitions in the younger cohort. Individuals born in the early 1970s where the first to benefit from these changes: in fact, the mean age at the end of school is close to 20 years of age. A higher premium on education and qualification also meant a later entry into the labor market. Additionally, the new institutional setting enabled intimacy to be more freely experienced, even if “experimentation” periods remain short, in comparison with another context within Europe [36].

A third conclusion is that departures from the normative sequence of events in the transition to adulthood have not changed radically. These departures occurred in more distant cohorts as well as in more recent cohorts. However, achieving residential autonomy before starting work became increasingly more common. Also, starting work almost always precedes cohabitation and parenthood. In fact, detailed analysis showed a high level of heterogeneity within cohorts, depending on gender and class origin. Moreover, departures from the “normative sequence” were clearly differentiated by gender and/or class origins. One key assumption in research on the life course is that, despite the persistence of highly gendered socialization processes, trajectories and transitions are being de-gendered, i.e., they are less likely to frame a double standard for men and women [18,66]. In addition, in fact, recent research has shown a blurring of gender differences in family and employment trajectories in recent age cohorts [13,67,68]. However, in the Portuguese context the period corresponding to the transition to adulthood remains gendered. Despite converging trends, for those born during the early 1970s, transitional periods are still longer for men than women. However, we should stress that in recent cohorts, gender differences are not substantial in what concerns public transitions (leaving school and entering the labor market), but mostly relate to private transitions (cohabitation and parenthood), which occur much later for men than for women. Additionally, the timing of men’s actual (later) transitions is in sharp contrast with their preferred calendar [42].

Finally, class origins continue to shape transitions to adulthood. However, cohort comparisons also indicate that classed transitions models have changed. While transitional periods were longer for all born in the early 1930s and for most born during the 1950s, there were sharp class differences concerning the timing of public transitions. Differences in the mean age of most transitional events are attenuated for those born during the early 1970s. However, if we consider the contemporary premium on academic achievement (namely on university diplomas), the disparity between those whose parents are Professionals and Managers or Industrial Workers remains highly meaningful in terms of life-chances. On the other hand, those we are able to extend schooling careers also tend to postpone or leave open-ended their private transitions, and that is more likely to happen for those from a bourgeois/petit bourgeois milieu. As shown by Guerreiro and Abrantes [37,44], structural conditions are a key element to understand why we are more likely to find early, gradual or precarious transitions among youths from a working-class background, where economic and cultural capital is scarcer, while experimental or ludic transitions are more likely to be experienced by individuals with a more affluent background. It is thus clear that class origins remain a factor for distinct biographical patterns, as clearly shown by the timing and pacing of transitions to adulthood.

Limitations

Our research has a number of limitations. Researchers have pointed out that transitions are increasingly reversible [25]. However, reversibility was not addressed due to the nature of the research instrument. On the other hand, even individuals from the most recent cohort were at least 35 years old. The challenges faced by current-day youths are very different. While we are aware that in the past few years change has accelerated significantly, our conclusions concern generations that are already in their mid-life. Another limitation concerns the time unit used to register transitions. Respondents were asked to recall events that happened a long time ago (for the oldest cohort up to 60 years ago). A number of individuals had doubts concerning the order of events or the precise date on which they occurred. While the usage of a life-calendar proved helpful, it would be unrealistic to ask individuals for more detail than a year in such a retrospective exercise. A possible consequence of this is a more “streamlined” account of their trajectories, not only as a result of selective memory but also because of the simplification and rationalization of an already distant past. Additionally, this research also does not address questions of subjectivity and meaning, which individuals attribute to their own trajectories. These are indispensable elements for a better understanding of the modalities of individual agency, in terms of intentionality, motivations, expectations, and choices. These issues should be addressed in future qualitative research.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia) within the framework of a post-doctoral project (SFRH/BPD/116221/2016).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Billari, F.C.; Liefbroer, A.C. Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Adv. Life Course Res. 2010, 15, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, M.C.; Kriesi, I. Transition to Adulthood in Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.P. The variable order of events in the life course. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1978, 43, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.P.; Astone, N.M. The transition to adulthood. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, J. Normative aspects of American marriage timing since World War II. J. Fam. Hist. 1980, 5, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfuss, R.R.; Swicegood, C.G.; Rosenfeld, R.A. Disorder in the life course: How common and does it matter? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M.J. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 667–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.M. Age and sequencing norms in the transition to adulthood. Soc. Forces 1984, 63, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, J.M. Cursos de vida, padronizações e disritmias. In Tempos e Transições de Vida: Portugal ao Espelho da Europa; Pais, J.M., Ferreira, V.S., Eds.; ICS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, R. The structure of the life course: Classic issues and current controversies. Adv. Life Course Res. 2005, 9, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R.A., Jr.; Mayer, K.U. The measurement of age, age structuring, and the life course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1997, 23, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.M. The order of events in the transition to adulthood. Sociol. Educ. 1984, 57, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nico, M. Transição Biográfica Inacabada. Transições Para a Vida Adulta em Portugal e na Europa na Perspectiva do Curso do Vida; ISCTE—Instituto Universitário de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, G.H.; Johnson, M.K.; Crosnoe, R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In Handbook of the Life Course; Mortimer, J.T., Shanahan, M.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K.U. Whose lives? How history, societies, and institutions define and shape life courses. Res. Hum. Dev. 2004, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, J.T.; Oesterle, S.; Krüger, H. Age norms, institutional structures, and the timing of markers of transition to adulthood. Adv. Life Course Res. 2005, 9, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.K. Sociological perspectives on life transitions. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1993, 19, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furstenberg, F.F. Reflections on the future of the life course. In Handbook of the Life Course; Mortimer, J.T., Shanahan, M.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 661–670. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, M. The institutionalization of the life course: Looking back to look ahead. Res. Hum. Dev. 2007, 4, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J.; O’Connor, H. A critical reassessment of the ‘complexity’ orthodoxy: Lessons from existing data and youth ‘legacy’ studies. In A Critical Youth Studies for the 21st Century; Kelly, P., Kamp, A., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, J.; O’Connor, H. Exploring complex transitions: Looking back at the ‘golden age’ of from school to work. Sociology 2005, 39, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M. The world we forgot: A historical review of the life course. In The Life Course Reader: Individuals and Societies Across Time; Heinz, W.R., Huinink, J., Weymann, A., Eds.; Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aboim, S.; Vasconcelos, P. From political to social generations: A critical reappraisal of Mannheim’s classical approach. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2014, 17, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, J.; Furstenberg, F.F.; Hershberg, T. Social change and transitions to adulthood in historical perspective. J. Fam. Hist. 1976, 1, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggart, A.; Walther, A. Coping with yo-yo-transitions: Young adults’ struggle for support, between family and state in comparative perspective. In A New Youth? Young People, Generations and Family Life; Leccardi, C., Ruspini, E., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, A.H. Becoming a young adult: An international perspective on the transitions to adulthood. Eur. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démogr. 2007, 23, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R.A., Jr. Passages to adulthood: Linking demographic change and human development. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démogr. 2007, 23, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovou, M. Regional differences in the transition to adulthood. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2002, 580, 40–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billari, F.C. Becoming an adult in Europe: A macro(/micro)-demographic perspective. Demogr. Res. 2004, S3, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Mendes, R.; Lapa, T. Families in Europe. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 7, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J. European welfare regimes and the transition to adulthood: A comparative and longitudinal perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 59, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzinsky-Fay, C. Lost in transition? Labour market entry sequences of school leavers in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvel, L.; Schröder, M. Generational inequalities and welfare regimes. Soc. Forces 2014, 92, 1259–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S. Patterns of labour market entry—Long wait or career instability? An empirical comparison of Italy, great Britain and west Germany. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 21, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, T.; de Graaf, P.; Hendrickx, J.; Layte, R. Vocational training and career employment precariousness in great Britain, the Netherlands and Sweden. Acta Sociol. 2003, 46, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.S.; Nunes, C. Transições para a vida adulta. In Tempos e Transições de vida: Portugal ao Espelho da Europa; Pais, J.M., Ferreira, V.S., Eds.; ICS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, M.d.D.; Abrantes, P. Transições Incertas. Os Jovens Perante o Trabalho e a Família; CITE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, W.I.L.; Gelissen, J. Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2002, 12, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aassve, A.; Billari, F.C.; Mazzuco, S.; Ongaro, F. Leaving home: A comparative analysis of ECHP data. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2002, 12, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, T.; Toulemon, L. Overview chapter 4: Changing family and partnership behaviour: Common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demogr. Res. 2008, S7, 85–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, P. Famílias complexas: Tendências de evolução. Sociol. Probl. Prát. 2003, 43, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Aboim, S. Cronologias da Vida Privada. In Tempos e Transições de Vida: Portugal ao Espelho da Europa; Pais, J.M., Ferreira, V.S., Eds.; ICS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; pp. 107–148. [Google Scholar]

- Elchardus, M.; Smits, W. The persistence of the standardized life cycle. Time Soc. 2006, 15, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M.d.D.; Abrantes, P. Como tornar-se adulto: Processos de transição na modernidade avançada. Rev. Brasil. Ciênc. Soc. 2005, 20, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.; Wall, K.E. Famílias Nos Censos 2011: Diversidade e Mudança; Instituto Nacional de Estatística/Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nico, M. Variability in the transitions to adulthood in Europe: A critical approach to de-standardization of the life course. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwin, D.F.; McCammon, R.J. Generations, cohorts, and social change. In Handbook of the Life Course; Kluwer Academic Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, H.; Mayer, K.U. De-standardization of the life course: What it might mean? And if it means anything, whether it actually took place? Adv. Life Course Res. 2005, 9, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, G. Holistic trajectories: A study of combined employment, housing and family careers by using multiple-sequence analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 2007, 170, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.; Tsay, A. Sequence analysis and optimal matching methods in sociology: Review and prospect. Sociol. Methods Res. 2000, 29, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulemon, L. Transition to adulthood in Europe: Is there convergence between countries and between men and women? In Research Note for the European Commission; INED: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M.C.F. Portugal e a Organização Internacional do Trabalho (1933–1974); Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.F.; Mauritti, R.; Martins, S.d.C.; Machado, F.L.; Almeida, J.F.d. Classes sociais na Europa. Sociol. Probl. Prát. 2000, 34, 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.F.d.; Machado, F.L.; Costa, A.F.d. Classes sociais e valores em contexto europeu. In Contextos e Atitudes Sociais na Europa; Vala, J., Torres, A., Eds.; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Billari, F.C. The analysis of early life courses: Complex descriptions of the transition to adulthood. J. Popul. Res. 2001, 18, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónica, M.F. Educação e Classes Sociais; Editorial Presença e Gabinete de Investigação Social: Lisboa, Portugal, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nóvoa, A. Política educativa do Estado Novo. In Dicionário de História de Portugal; Barreto, A., Mónica, M.F., Eds.; Figueirinhas: Porto, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Casaca, S.F. A (des)igualdade de género e a precarização do emprego. In A Igualdade de Mulheres e Homens no Trabalho e no Emprego em Portugal: Políticas e Circunstâncias; Ferreira, V., Ed.; CITE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, V. Informality, stability and precarity: A sequential analysis of occupational trajectories over the last few decades. Sociol. Probl. Prát. 2017, 84, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mauritti, R. Viver Só: Mudança Social e Estilos de Vida; ISCTE—Instituto Universitário de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, M.d.D.; Caetano, A. Pessoas sós em Portugal: Evolução e perfis sociais. In Famílias Nos Censos 2011: Diversidade e Mudança; Delgado, A., Wall, K., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Estatística/Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014; pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, S.d.C.; Mauritti, R.; Costa, A.F.d. Condições Socioeconómicas dos Estudantes do Ensino Superior em Portugal; DGES/MCTES: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005.

- Cunha, V. Trajetórias não reprodutivas em três gerações de portugueses: incidência, circunstâncias, oportunidade. In VII Congresso Português de Sociologia: Sociedade, Crise e Reconfigurações; Associação Portuguesa de Sociologia: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, V. Quatro décadas de declínio da fecundidade em Portugal. In Inquérito à Fecundidade 2013; INE/FFMS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, F. O salazarismo e o homem novo: Ensaio sobre o Estado Novo e a questão do totalitarismo. Anál. Soc. 2001, XXXV, 1031–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, A.; Cartmel, F. Young People and Social Change: New Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga, C.H.; Liefbroer, A.C. De-standardization of family-life trajectories of young adults: A cross-national comparison using sequence analysis. Eur. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démogr. 2007, 23, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Widmer, E.D. Gendered Life Courses between Standardization and Individualization: A European Approach Applied to Switzerland; LIT Verlag: Zürich, Switzerland; Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Translated from Portuguese by the author. |

| 2 | Fieldwork was completed by a subcontracted field agency (GFK/Metris). |

| 3 | Since each of five events may or may not have occurred, the number of potential combinations is ((5*2)!/((5*2 − 5)!*5) = 252. |

| 4 | Only in 1971 work for those under 14 years was outlawed [52]. In 1991, in the face of a worrying persistence of child labor, the minimum age to work was raised to 15 years of age and further extended to 16 in 1997 (Diário da República, I Série-A, n.° 238/91, Decreto-Lei n.° 396/91). Only in 1998, Portugal adhered to the ILO Convention (138), which establishes the minimum age for admission to general employment at 16 years of age, and 18 years for those in public functions (Diário da República, I Série-A, n.° 66/98). |

| 5 | As a marker for leaving school, we considered the proportion of individuals that completed secondary education. |

| 6 | For the sake of parsimony, we only consider the 30-year-old threshold, which is the most commonly used in research on transitions to adulthood. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).