Abstract

In response to research which argues that people living with a disability (PLWD) face societal barriers including workplace participation, this study explored how the barriers to social participation, specifically workplace participation, faced by PLWD are exacerbated by the lack of appropriate clothing and the role that stigma, self-efficacy, and clothing have in workplace participation. Finding appropriate clothing is a significant barrier to social participation for many PLWD. The social model of disability used in this study supports this by suggesting that it is society which places barriers to PLWD rather than their disability. A qualitative inquiry of semi-structured, in-depth interviews was used, and the results showcase six sub-themes of barriers: work defines me, disability as the barrier to workplace participation, work allows extra societal opportunities, stigma questions my self-efficacy, workplace accommodations diminish my stigma, and clothing builds my self-efficacy. The study found that, for PLWD, workplace participation is hindered because of occupational typecasting and lack of appropriate clothing, which increases their stigma and decreases their self-efficacy. The contributions of this study include theory support, policy, community, and educational enhancement.

1. Introduction

According to the 2014 U.S. Census Bureau’s (CB) American Community Survey, the population of people of working age living with a disability (PLWD) is estimated at nearly 19.8 million. For PLWD, the employment rate is 34.6% compared to 77.6% of non-disabled people [1]. Among PLWD who are employed, the highest rate of employment is among people with a hearing disability at 51.2%, while the lowest rate is among people with a self-care disability at 15.5% [1]. Self-care disability is described by the CB as difficulty dressing or bathing and is linked to activities like difficulty navigating one’s home, getting in and out of bed, dressing, eating, or using the toilet [2]. These figures suggest that there is a significant portion of PLWD of working age, able to perform daily activities without assistance, and able to seek and hold employment.

According to Haegele and Hodge [3], there are two main models of disability. The first is the medical model of disability, which is defined as an impairment of the body or its functions resulting from a medical or individual incident. The second is the social model of disability, which focuses on the social restriction placed on the body impairment. In other words, it is not the disability that prevents a person from fully participating in society, rather, it is society that creates barriers for participation. Impairment can be classified as lacking all or part of a limb, a defect within a limb, lacking body motility, or restricted activity due to lack of accommodation allowing full participation in society [4]. Therefore, this research chose to use the social model of disability when exploring the issues concerning the social barriers facing PLWD; it is important for those barriers to be contextualized from the lens of the relationship between the person with the impairment and the society.

Particularly, it is suggested that lack of appropriate clothing might be one key social barrier of PLWD’s workplace participation [5]. Workplace participation affords everyone, including PLWD, the opportunity to gain economic, emotional, and social benefits. For PLWD, workplace participation improves not only their economic status but also their social and psychological status, making them feel they have purpose [6,7]. However, for many PLWD, access to acceptable and appropriate clothing serves as a barrier to full participation in the workplace [5,8]. That is, PLWD may feel unsuccessful in their occupations because of their lack of acceptable and appropriate clothing. Lack of acceptable and appropriate clothing can make PLWD feel as if they are not taken seriously in the workplace and can draw more attention to their disability, causing further stigmatization [9,10].

PLWD build self-efficacy through interaction and social feedback, including within the workplace [11]. When PLWD encounter negative social feedback within the workplace, they may experience stigma associated with their disability causing them to feel as if their disability prevents them from full participation in society [6]. Clothing can protect PLWD from stigma and enhance their self-efficacy, especially if they can find appropriate and acceptable clothing [11,12]. Despite the potential impact of clothing on stigma and self-efficacy of PLWD, little is known about how they affect workplace participation for PLWD. Specifically, the impact of clothing on PLWD’s workplace participation have not been discussed within the social model of disability perspective. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore how the barriers to social participation, specifically workplace participation, faced by PLWD are exacerbated by the lack of appropriate clothing, and how this lack of appropriate clothing may lead to increased feelings of stigma and decreased self-efficacy. The findings of the study are expected to shed light on how clothing plays a role in PLWD’s social participation, especially workplace participation, and to demonstrate the need for availability of appropriate clothing for PLWD, which can improve their feeling of self-efficacy and decrease their stigma.

1.1. Goals of PLWD’s Workplace Participation

An increasing number of PLWD have entered the workforce since the passage of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) in 1990. Workplace participation can be particularly important for PLWD as it has economic, emotional, and social benefits. For most of the working population, including PLWD, workplace participation improves their economic, social, and psychological status [6,7]. According to Blustein [13], workplace participation consists of four key components: (a) Work provides the world a view of our outward identity; (b) Work has a personal meaning influenced by societal and cultural influences; (c) Work is a basic activity that contributes to our overall economic stability; (d) Work brings people together as one constant experience across cultures and time. This is true for both PLWD and non-disabled.

More specifically, for PLWD, the ability to engage with others and the environment within the workplace decreases social isolation and helps build social capital [7]. According to Schur [7], workplace participation can help increase life satisfaction by developing skills that let PLWD feel useful. Araten-Bergman and Stein (2014) stated that for PLWD to fully participate in society, they must be able to: (a) Choose meaningful employment so they can support themselves; (b) Achieve equality within society and culture; (c) Achieve high-quality physical and mental health and well-being. Araten-Bergman and Stein [14] have aligned their workplace concepts for PLWD with those of Blustein [13], which apply to all workplace participants. This suggests that, for PLWD, full and active [14] participation provides PLWD with a higher quality of life.

Furthermore, Blustein [13] theorizes that work is an opportunity to develop power. For example, he suggests that people work to gain economic independence which affords them the luxury to invest in their social status, such as owning property or gaining higher education. Bluestein [13] further postulates that this investment leads to empowerment and privilege and provides an opportunity to wield power within the community, allowing for a greater level of social participation. He describes power as one’s ability to control actions within their environment. This type of power can be applied to PLWD as they work to gain independence that, in turn, affords them the luxury to invest in their social status. This investment, for PLWD, can build higher levels of self-efficacy [13].

Despite the importance of workplace participation, some PLWD have limited workplace options. Duffy et al. [15] argued that disability can be a barrier to employment, which limits the ability of PLWD to achieve their career goals and instead drives them to find work that will simply sustain them. Using the Psychology-of-Working Framework, Duffy et al. [15] demonstrated that marginalized populations often lack freedom of choice in their career goals, and the more barriers faced, both subjective and realized, the less freedom they experience when choosing careers or employment. The findings by Duffy et al. [15] are supported by Fadyl and McPherson [16], who suggest that people with a spinal cord injury (SCI) who were returning to work had to find ways to manage the barriers they faced as a consequence of their injury, so as to regain the employment options they possessed prior to the injury.

In addition to their physical limitations, PLWD face barriers to workplace participation in relation to their lack of appropriate clothing. There are few workplace-appropriate clothing options in the marketplace, so few that many PLWD feel as if they are unable to fully participate in society because of the lack of appropriate clothing [5,8]. Although the authors of these studies show the potentially important impact of clothing in PLWD’s workplace participation, an in-depth understanding, with first account knowledge, of how the lack of appropriate clothing serves as a barrier to workforce participation experienced by PLWD is limited. To better understand this impact for PLWD, the researchers deemed it necessary to understand the goals of workplace participation expressed by PLWD, which may or may not be consistent with the current literature. This understanding helped guide the research questions and allowed for a better understanding of the impact workplace participation has for each participant and its relationship with stigma and self-efficacy. Therefore, the first research question was developed:

RQ1: What are the goals/purposes of workplace participation expressed by PLWD?

1.2. Stigma Experienced by PLWD

According to Miller [11], people develop self-efficacy and confidence through social feedback. PLWD receiving negative social feedback may experience stigma due to their disability, and stigma could become a main barrier impacting their ability to accomplish life goals and to fully participate in society (Corrigan et al., 2009). There are two types of stigma: public and self [6]. Public stigma develops on the basis of how people perceive or react to PLWD and is built upon these key factors: (a) Stereotypes, the knowledge learned by those in one social group about those in other social groups; (b) Prejudice, the endorsed stereotype accepted about PLWD; (c) Discrimination, an outcome of prejudice. Discrimination manifests in three ways for PLWD, i.e., (a) loss of opportunities, such as not being hired for a job because of a disability; (b) coercion; (c) segregation [6,17]. On the other hand, self-stigma is associated with the acknowledgement, agreement, and internalization of the negative stereotypes experienced by PLWD [6,17,18]. Self-stigma has been referred to as the “why try” [6] (p. 75) effect and consists of three foci: (a) results of self-stigma from stereotypes; (b) self-efficacy; (c) life goal achievement or the lack thereof [6]. Often, the “why-try” effect is further exacerbated by the clothing that PLWD are forced to wear because they are unable to find clothing they feel appropriate for the social situation [9].

1.3. PLWD’s Self-Efficacy

In dealing with stigma, Miller [11] posited that, for PLWD, appropriate clothing can offset negative social feedback. That is, if clothing is designed to consider the physical limitations of PLWD, it can reduce their dependence on others for assistance. In addition, clothing deemed appropriate by PLWD may reduce negative social feedback and increase their social interaction and self-efficacy [11]. Self-efficacy is defined by Bandura [19] as the belief in your ability to perform specific activities. According to the social cognitive theory (SCT), these beliefs help determine which activities and roles will or will not be approached, how people feel when engaged in the activities, and how long people engage in the activities [20]. Lent [21] suggests that relationship-inferred self-efficacy, or my biased assumptions regarding how others see my abilities, can improve the feeling of self-efficacy among PLWD when experiencing challenges and doubting their capabilities.

According to Bandura [20], self-efficacy is central in SCT as it directly affects action but also impacts goal setting. The belief in one’s ability is what guides people to accept particular challenges and, therefore, establish goals for achievement [20]. Bandura [20] suggested that if people believe they are unable to accomplish a challenge and be successful, they are more likely to give up and settle for a lesser outcome, and conversely, belief in their own ability will motivate people to overcome challenges and achieve the established goal. That is, people with high efficacy will visualize their success much easier than those with low efficacy, and people with higher efficacy have a greater ability to navigate or overcome environmental and societal barriers and still succeed [20].

Particularly, clothing can serve as a way to build higher efficacy and help PLWD navigate the societal barriers they face. Clothing is both an external cue used by individuals to project a desired image to society and an internal cue which allows an individual to express self-identity and accommodate self-efficacy in the roles in which he or she engages [22]. For PLWD, these considerations are even more personal. They must consider whether or not the clothing required for the job will allow them to remain independent or if they will need additional assistance. As discussed by Solomon and Douglas [22], people who are new to a social situation will rely on that environment to provide cues as to appropriate behavior. This, in turn, will cause people to search for and acquire products perceived as exemplar [22] for that social environment. If they feel as if they are unable to acquire the necessary products for the social environment for which they strive, they will develop uncertainty in their ability to participate within the social environment, and as a result, their self-efficacy will diminish.

Role of Clothing in Stigma, Self-efficacy, and Workplace Participation

Lack of appropriate clothing, as an external stigma factor, is discussed in the literature as a potential additional societal barrier for PLWD’s appearance and stigma management and, therefore, workforce participation. Freeman et al. [9] found that the non-disabled are likely to focus on the disabling attributes of PLWD, creating a stigmatized view. In addition, Freeman et al. [9] suggested that when PLWD use functional or adaptive clothing, they feel the clothing draws more attention to their disability instead of minimizing it. Further, the authors found that the majority of PLWD believed clothing and appearance were important in how non-disabled people engaged with them, and that visible disabilities enhanced more negative attitudinal barriers for non-disabled people engaging with PLWD. More interestingly, the authors found that, despite the attitudinal barriers PLWD faced, these attitudinal barriers would be eliminated if they had clothing they felt was attractive and appropriate. Another factor of interest from the Freeman et al. [9] study is that the majority of PLWD want to look like everyone else (i.e., non-disabled) and believe that access to appropriate clothing would help them feel accepted. The Freeman et al. [9] study supports other literature which suggests that, for most PLWD, functional or adaptive clothing prevents them from feeling accepted in society. PLWD feel as though their clothing stands out and draws attention to their disability instead of minimizing it [12,23,24].

In this light, Lamb [25] suggested additional research is needed in the areas of access, clothing barriers, and equal opportunity for PLWD. She referenced the need for scholars to determine if PLWD can find appropriate clothing for specific life events, and whether PLWD are satisfied with the clothing available to them. Lamb [25] further suggested that, just as disability scholars study the civil rights of PLWD, textile and clothing scholars could focus on how clothing items are made available to PLWD for use in their development of identity [25]. Lamb [25] took the lack of appropriate clothing as a barrier to social participation one step further, suggesting that economic barriers and specific physical disabilities may worsen the problem of finding appropriate clothing for job interviews that communicate a neat and tidy appearance. Despite these challenges, little is known about how clothing affects PLWD’s stigma, self-efficacy, and workplace participation decisions. Therefore, the second research question was developed:

RQ2: What are the roles clothing plays in stigma, self-efficacy, and workplace participation among PLWD?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Inquiry

Given the exploratory nature of the research, a qualitative inquiry of semi-structured, in-depth interviews was conducted. Using a semi-structured approach to the in-depth interview allows the researcher to guide the exploration initially and then divert questions accordingly as the participants explore their own experiences, providing a more rich and organic experience to the inquiry [26]. The questions used for this study were derived from previous qualitative research conducted by the researchers [5,8]. During previous studies, the researchers discovered that participants experienced barriers to workplace participation as a consequence of unmet clothing needs, and this directed the questioning for the current study.

2.2. Participants

The participants in this study were located in the state of Missouri in a small town with a population close to 120,000. Participants were chosen using purposive sampling with maximum variation goals so as to provide a cross section of PLWD who experienced barriers to social participations because of their physical or psychological disabilities, see Table 1. Purposeful, maximum variation sampling allows for an exploratory approach to the population of PLWD to better understand the barriers they face [27]. After approval from the Institutional Review Board, the participants were selected on the basis of whether they had sought or were seeking employment, or whether they had worked or were working. Further, the goal of this research was to better understand how workplace participation impacted them. Just as each disability provides a unique set of challenges, the researchers felt it necessary to explore the variations and differences which might appear among the participants [28].

Table 1.

Participant Descriptions.

The researchers, who had worked with disability advocates previously as well as in previous research studies, used their experience and connections in the disability community to solicit participation from a network of disability advocates, caregivers, and PLWD, interviewing a total of thirteen participants. All 12 participants were disabled. Of the 12 participants, half reported physical disabilities ranging from SCI to Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Muscular Dystrophy (MD), while the other half reported psychological disabilities including Attention Deficit–Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Anxiety Disorder, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Although 12 participants may seem like a small sample population, the data gathered were diverse and robust and indicated duplicative emerging themes among all participants [29].

2.3. Data Collection

The semi-structured interviews took place in spring 2017 in locations convenient, accessible, and private for the participants. Each interview took between 30 and 120 min and was audiotaped and then transcribed. For example, for research question 1, questions such as “Tell me what workplace participation means to you” and “Describe what being employed means to you” were asked. For research question 2, regarding stigma, self-efficacy, and clothing as it relates to workplace participation, the following types of questions were asked: “Describe your experiences when applying for a job”, “Describe a time when you didn’t apply for a job because of your disability and the factors which prevented you from applying”, “Discuss a time when you applied for a job and clothing requirements were a factor in your decision to accept a job”, and “Describe how prepared/qualified you feel you have been for the jobs for which you have applied for or held.”

2.4. Data Analysis

To support the rigor and trustworthiness of the data collected, the researchers utilized the following methods of triangulation: (a) Participants with various type of physical disabilities were involved in the study, (b) Participants were recruited from a variety of locations within the town and organizations, and (c) The researchers used a constant comparison analysis along with word count to better understand and capture the emerging themes. As can be seen in Table 1, the participants demonstrated diversity in disability, gender, age, occupation, and experience. Using a wide range of participants allowed the researchers to witness individual views and experiences, which provided a deeper understanding of the participant’s attitudes and needs as they related to the unmet clothing needs that serve as barriers to PLWD [30]. Further, recruiting participants from a variety of locations, backgrounds, and organizations helped to insert greater credibility into the findings by demonstrating consistent findings across the demographic [30]. Finally, using a variety of qualitative analysis tools allowed for increased credibility of the findings and allowed the researchers to trust the themes which emerged during the analysis [31].

The constant comparison analysis process of thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke [32], was used by the two researchers, and followed six steps in the interpretation of the data: (a) immersion in the data, (b) development of initial codes, (c) searching for themes, (d) reviewing themes, (e) defining themes, and (f) selection of vivid and compelling examples. The first step, immersion in the data, required a detailed review of each transcript. This process was interpretive, with both researchers constructing and detailing their version of what the data suggested and looking for meanings and themes throughout the dataset [29]. It was during this step that initial notes were made regarding possible themes and were compared between the researchers.

Following the review of the data, the second step, development of initial themes, began. Each researcher compared the two research questions to each interview and generated a master, color-coded list to identify each theme. The initial theme categories were: (a) workplace participation, (b) stigma and self-efficacy, and (c) the role of clothing in PLWD’s lives. Relevant content was highlighted by each researcher according to comments made by the participants; the goal was to look for as many connections as possible to the two research questions. In some cases, participant comments overlapped the research questions. When overlap occurred, the researchers used multiple color codes to designate that passage.

The third step, searching for individual themes under the three theme categories, began with the categorization of the research interpretation and analysis [32]. Both researchers worked collectively to create a document detailing the progression of the interpretation analysis. This document allowed for a more analytical approach to the interpretation of the data, which assisted the researchers in finding critical connections that may have been more difficult to see when simply reviewing the transcribed text [29]. The first stage of step three involved sorting the coded content into themes. Initially, 21 themes were identified within the workplace participation category, 39 themes were identified within the stigma and self-efficacy category, and 31 themes were identified within the role of clothing category. Word count was also employed during step three. Both researchers searched for key words used by participants that reflected either unmet clothing needs or barriers they faced in workplace participation. These words were used in establishing the themes. The participant number was placed next to each theme or word to designate the connection to each theme and to allow for location of examples later in the analysis process. These themes were documented as descriptive explanations of what was presented by the participant during the interview and were guided by the theoretical framework used for this research study [29]. Using a descriptive explanation process provided a connection to the initial themes and the research question.

The fourth step, reviewing themes, required the researchers to take a detailed look at the initial themes to identify recurring patterns. These patterns allowed the researchers to categorize using two criteria: “internal homogeneity” and “external homogeneity” [33] (p. 403). Internal homogeneity categorizes data by how they connect to each other in a significant way, whereas external homogeneity categorizes data by the differences among the categories. Through this process, 21 initial workplace participation themes were narrowed down to 3, and 39 initial stigma and self-efficacy themes were narrowed down to 2. It was during this process that the researchers found overlap in the role clothing played in workplace participation, stigma, and self-efficacy and combined these concepts to demonstrate the relationship.

During the fifth step, defining themes, the participant stories began to develop through the refinement of themes [32]. For workplace participation, the three themes were: (a) Work defines me; (b) Disability as the barrier to workplace participation; (c) Work allows extra societal opportunities. For "appropriate clothing improves my stigma and self-efficacy", the three themes were: (a) Stigma questions my self-efficacy; (b) Workplace accommodations diminished my stigma; (c) Clothing builds my self-efficacy. Finally, the last step, selection of vivid and compelling examples, resulted in the researchers reviewing the transcribed data a final time to pull examples which supported the story being told within each theme and sub-theme. These examples were chosen because they captured the very essence of what was being described by theory and they demonstrated how PLWD view workplace participation as a mechanism for providing opportunities and challenges which can be overshadowed by stigma and self-efficacy [32]. Overall, through interactions and discussions between the two researchers, a 100% of interpretation agreement was achieved.

3. Results

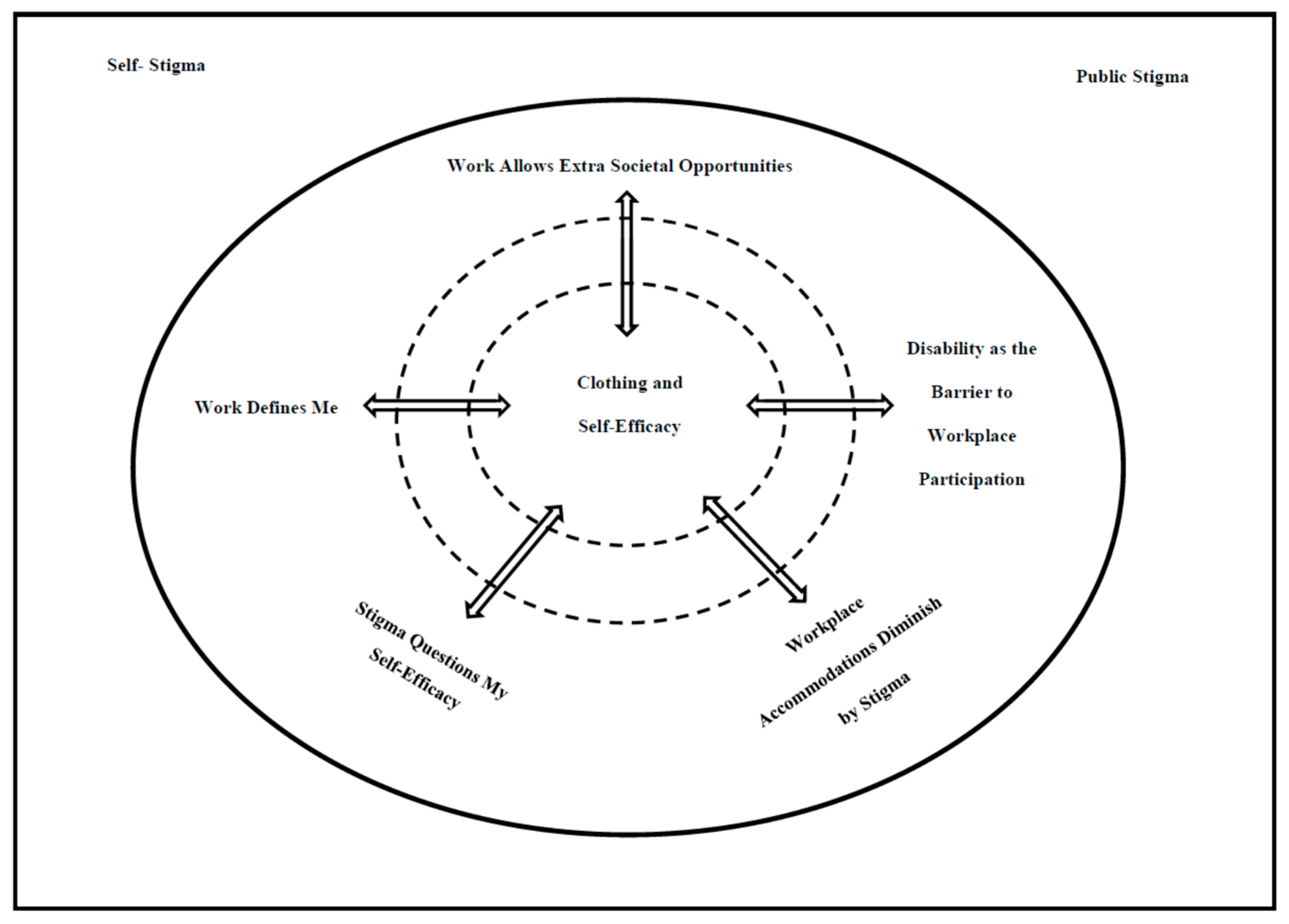

Overall, six themes emerged from the data with three themes for each research question. Figure 1 shows the summary of the results.

Figure 1.

Goals of Workplace Participation for PLWD and Their Challenges.

3.1. Worklplace Participation Goals Are Varied

Overall, three key themes emerged from the study data, showing PLWD have various goals for workplace participation. They were: (a) Work defines me; (b) Disability as the barrier to workplace participation; (c) Work allows extra societal opportunities.

3.1.1. Work Defines Me

Under this theme, two sub-themes emerged: work makes me feel productive, and work builds my social capital. First, 10 out of 12 participants (83%) described work as “making them feel worthwhile and productive.” P9, who was recently injured and lives with an SCI, said going back to work meant getting back to “the productive level” he had before his injury and “conquering the challenges” he faced in doing so. He further discussed the need to have a plan for employment post-injury, which allowed him to “measure my [his] ability to function in my [his] old environment.” Similarly, P12, who lives with multiple psychological disabilities that once drove her to attempt suicide, said that work was the place where she could feel as if “people needed her” and she was not just completing her duties. P12’s response supports Schur’s [7] argument that work provides a sense of acceptance in society for PLWD, because to the participants work is more than being accepted, rather, it is about being needed, conquering their productivity to prove they can do their job as effectively as those without a disability, and being productive members of society:

P9: Well, it’s changed, the reasons have changed, or new reasons have been added [reason for working]. Since I was injured, which was about 3 years ago, it was very important to me to try and do everything in my life that I’d done before. I wanted to see how much of it I could conquer and get back…I…decided that I wanted to see how productive I could be and reach my former levels of productivity prior to the injury. I had a 5-year plan to do that…my employment became important to me as a way for me to measure my ability to function in my old environment given my new disability.

P12: Because, especially someone with disabilities, it’s already hard to feel like a burden on others because you need to have people in your life that are…open and wanting to help you, but there’s still that underlying…feeling of being a burden. . . you want to work to feel like people need you…rather than simply completing duties.

Second, nine out of 12 participants (75%) shared that work is about “feeling confident and building social capital”, further expanding Schur’s [7] perspective that work provides a sense of acceptance in society for PLWD. To the participants, work “gives back” (P10) and builds “social capital” (P4), so they can live independently and productively. P10, who was diagnosed with MS and previously worked as a bank executive but currently works as a patient representative in a hospital, believed work provided her with “a sense of confidence and self-worth” beyond simple productivity. She discussed the need to find work that made her feel as if she was “giving back and not taking from her community.” This is similar to P4, who was diagnosed with MD in childhood and currently works for a disability non-profit. He shared that he discovered he could build his “social capital” through work and believed it gave him “the privilege to serve as a role model to other PLWD.” He discussed how his parents told him he could do whatever he wanted to do, despite his disability, and that it was up to him to show others what he was capable of doing. These values seem consistent with the findings of Araten-Bergman and Stein [14] who emphasized the need for PLWD to develop social capital as a means to overcome the marginalization they face and to increase their feeling of well-being, suggesting that expressing one’s identity can help PLWD to achieve a sense of connection to society:

P10: It [working] is important because I feel confident. Well, I used to feel more confident than I do now [she used to be a bank executive], but I could probably do something that would be worthwhile and give me some sense of self-worth. I always felt like my employment did that for me and made me feel good about myself and that I was helpful.

P4: It’s just…people with disabilities want to be out in the community. This idea of social capital, I did not understand that concept until I heard that from my director…and then as I’m seen in the community . . . I now understand that…and I started living it. People started noticing me and started seeing me different places, and then they’re like, “Oh that guy, he’s always out so…it must mean something and he doesn’t just stay home and do nothing.” …I feel I can participate and that I am a valued member.

3.1.2. Disability as the Barriers to Workplace Participation

Under this theme, two sub-themes emerged: work is my second choice, and work is frustrating to me. First, for seven of the 12 participants (58%), work offers a limited opportunity, and was seen as less of a choice in the type of job they sought and more of a feeling that they were typecast into a job that focused on PLWD. For most, this type of employment was not their first career choice. Rather, because of their disability, they found they were limited in their employment options. P1, who is living with an SCI suffered during a car accident as a teenager, had always aspired to be a politician or a journalist. However, because of his disability, his dream was discouraged, and after a brief stint in public office, he had to settle with employment options in disability advocacy organizations. Although some may believe his employment options were good options, he felt the options provided him with no reprieve from his disability. He felt he could do more and wanted to do more to fulfill his childhood dream. Be that as it may, potential employers did not see his full potential, and he felt like he had to take these jobs in order to earn a living. P1’s comments are consistent with Duffy et al. [15] who posited that disability can be a barrier to employment which limits one’s ability to achieve their career goals, so that PLWD find work which will simply sustain them.

P1: Honestly this isn’t as interesting as it was being in politics. It was a job I wanted to do since I was a little kid…so you are lucky if your dream as a kid was to be a fireman and you got to do that, most people never get to be what it is they wanted to be. So, that [politics] had a lot of personal meaning and interests because my life didn’t just revolve [around] disability questions and issues all the time. Now, I’m back in a rut, so to speak, talking about disability stuff all day and then I go home and live with it too. So, it’s [my current work] valuable but it’s not interesting.

Second, four other participants (33%) stated their frustration with the limited accommodations within their workplace. Their frustration ranged from a lack of physical environmental accommodations to the limited ability to fulfil their job requirements. For example, traveling is discouraged because it would require additional accommodations or support. For these participants, a detailed plan is required to accommodate their travel, including making arrangements for someone to drive them or confirming that their destination could accommodate their disability. P9, who is an engineering professor (Ph.D.) living with an SCI and using a wheelchair, shared a feeling of “being left out” from his professional responsibilities because of cumbersome travel requirements due to his disability. Prior to his injury, he was a consultant who travelled the country, consulting on construction projects such as roads and bridges. However, since his injury, he had to limit his travel, forced to watch on the sidelines as a spectator rather than an active participant. Although he feels fortunate he can continue consulting, albeit in a reduced role, he feels these additional accommodations limit his career opportunities. P9’s view was consistent with Fadyl and McPherson's [16] who found that, when returning to work, people with SCI felt challenged to modify or adjust their methods of work in light of their SCI:

P9: Probably…what’s hindering me now is my mobility, specifically on the research and funding side. I go and meet and interact with a lot of people, travel to potential funders at companies. Now everything takes a lot of planning and adjustments, more time and, from that perspective, I know I haven’t been able to become as productive, funding-wise, as I was before I was injured. I work in a lot of different industries, engineering consulting firms, contractors, construction, and typically that involves a lot of face-to-face meetings, and going to project construction sites is very difficult. The way I handle it now is I find a graduate student who can travel with me, and they are my eyes and legs because they can get around. They are good, but I feel a little bit left out because that is what I enjoy doing. So, that is a little frustrating.

3.1.3. Work Allows Extra Societal Opportunities

Six of the 12 (50%) participants mentioned that work allows them to plan for future societal opportunities. Consistent with Blustein [13], who theorized that work is an opportunity to survive and develop power and is an investment for empowerment and privilege, P10, a patient representative in a large hospital, stated that work allows her extra time and help for her family. She is on her second career, retired from a career as a bank executive, and her current employment allows her to take her grandchildren on trips and support their extracurricular activities, providing her a sense of giving back. P10 stated she would not have been able to afford the power to provide “extras” for her family without her current employment. Similarly, P12, a college student living with multiple psychological disorders after suffering a trauma as a child, stated she wants to help kids who have experienced similar traumas. For that purpose, she specifically chose art therapy as a major to help kids understand that what they went through was not their fault. Because of her disability, P12 decided to pursue the art therapist track as she believed it would give her additional power to give back to her community. Ultimately, she shared that her work would provide a better quality of life for people who have experienced trauma during their childhood. For these participants, their employment goals and aspirations are luxury, beyond survival tools.

P10: Employment to me right now means I am able to enjoy a little bit of extras that I wouldn’t necessarily be able to enjoy at this stage in my life, also I’m able to contribute to my grandchildren’s enjoyment and hopefully [be] worthwhile [and] help with their education and things like that.

P12: I want to be an art therapist for kids that have been through trauma, and specifically working with kids with ADHD. …I just want to be able to work with kids through art therapy and help them understand that nothing’s wrong with them, they just do things in a certain way. That’s not wrong or bad, it’s just different…I had art therapy through rehab, and it was the best thing in the world. [Researchers’ observation: She was so excited and more animated while talking especially about the role of art therapy in her life’s transformation. It seemed she truly believed in the power of art therapy and potential healing that she could offer to future victims].

3.2. Appropriate Clothing Improves My Stigma and Self-Efficacy

In this theme category, three major themes emerged: (a) Stigma questions my self-efficacy; (b) Workplace accommodations diminish my stigma; (c) Clothing builds my self-efficacy. Overall, 10 of the 12 study participants (83%) shared that “their self-efficacy was reduced because of the stigma they experienced,” going from a high-level to a low-level of self-efficacy. In addition, seven of the 12 study participants (58%) stated that initially stigma negatively impacted their self-efficacy. These findings were consistent with Corrigan, Larson, and Rüsch [6] who suggested that stigma can have both a negative and a positive effect on the person experiencing it, directly impacting their ability to succeed. In this study, eventually all seven participants were able to overcome the stigma they faced and develop a high-level of self-efficacy, using their self-efficacy and internal power to turn their stigma into a positive force allowing them to continue participating in society [6].

3.2.1. Stigma Questions My Self-Efficacy

P7, a graduate student in clinical psychology with multiple psychological disorders including ADHD, anxiety, and depression, never felt as if her disability impacted her ability to succeed. She always felt she was “smart enough” and that her disability would not prevent her from fully participating in the workplace. However, graduate school was different; after several months of struggling to meet the deadlines expected of her degree program, her confidence waned, and she approached her advisor about her disability, hoping for support and accommodations. She was disappointed to find her advisor was not supportive and did not believe her disability was the factor; she was labelled as “lacking professionalism.” This led to a feeling of being “alienated and ignored.” P7 was finally granted accommodations but felt the damage had already been done, and her high-level of self-efficacy was so diminished she felt forced to reconsider her career goals. Prior to this experience, her goal was to acquire a tenure-track position at a research-intensive institution. However, after being told she was not professional and she should drop-out of the program, she questioned her ability to be successful.

This experience is similar to that of P1, who felt limited in his career opportunities because of his perception of being typecast into positions focused on disability, though he wanted to continue a career in politics. For both, their disability impacted their preferred career options. This can be explained by Bandura [20] who suggested that people are impacted by their own successes and failures and develop standards based on their motivation and behavior. As seen in both P1 and P7, the external stigma negatively affected their self-efficacy, ultimately changing their career-goals and the trajectories of their futures:

P7: When I first came in [to the Ph.D. program] I…felt smart enough. I felt very confident in myself, and over the years that has been wearing down. [Then] I have been told by my advisor…“I don’t think you are a PhD student. I think you are just a master’s student. Why don’t you just drop out?” This was totally out of the blue. But I used to want to be an R-1 research professor. I am definitely questioning, are these people right, with my disabilities, can I really do this?

3.2.2. Workplace Accommodations Diminish My Stigma

P10, a former bank executive who currently serves as a patient advocate in a large hospital, initially developed a low-level of self-efficacy after her disabilities forced her to take a detour in her career path. Before the disability, her goal was to begin a second career in nursing. After enrolling in nursing school, she suffered a heart attack and shortly thereafter developed a perforation in her colon and had to undergo colon surgery. She was forced to rethink her ability to complete nursing school, so she dropped out and applied for another job at the hospital as a patient advocate. After taking this job, she suffered another health emergency when she was diagnosed with MS. This diagnosis meant she was no longer physically able go to her patients. So, her supervisor moved her into a different role as an outpatient counselor and provided her with an office where the patients could come to her. With her health issues and developing disabilities, P10 felt her self-efficacy and confidence wane, initially. However, when her supervisor offered to accommodate her disability and move her into a new position, her confidence level soared.

P10: Well, actually my boss has been very accommodating as far as the surgeries…I was called an inpatient counsellor…when I first started…and I’d go up to the floors and meet with patients and interview them while they were in bed, and after the colon surgery and 40 days in the hospital and three surgeries and a colostomy bag, she [her supervisor] said, when you are able to come back we’ll make you an outpatient counselor, and I said thank you so much. That was really great. I can sit in my office and help people on the phone or help people that walk in the door.

P10’s experience is similar to P9's who experienced lower self-efficacy because his disability required him to adjust his travel arrangements when visiting construction sites. While P10’s self-efficacy improved when her supervisor provided accommodations and took a positive approach to her disability, P9 faced a lowering of his self-efficacy because of his inability to conduct construction site visits as he had done prior to his disability. However, P9 was determined to continue this role so he used his relationships with his graduate students to accommodate his disability and continue visiting constructions sites, albeit in a slightly different capacity; his self-efficacy increased through self-determination. Both P10's and P9’s experiences are supported by Lent [21] who stated that the relationship one has with others can improve their feeling of self-efficacy when they experience challenges and doubts of their capabilities. For P10, she began to experience a lowering of self-efficacy and doubted her ability to do her job, but when her supervisor moved her into a new position and made accommodations, she felt as if her supervisor believed in her and, therefore, her self-efficacy increased. For P9, Lent’s [21] theory supports the shift in his self-efficacy from low to high because of the relationship with his graduate students to conduct the investigations for him so he could continue his work.

3.2.3. Clothing Builds My Self-Efficacy

Interestingly, participants raised clothing as a tool to build or enhance their self-efficacy throughout social or professional interactions. Indeed, the lack of appropriate clothing can be a barrier to social participation among PLWD [8]. For seven of the 12 study participants (58%), the need to find clothing which made them appear more “professional” was critical to their workplace participation. P7, a graduate student in clinical psychology with multiple psychological disorders, stated that prior to entering her Ph.D. program she had a very distinctive clothing style, one which was more eclectic, supported [8]. She had always felt comfortable demonstrating her personal style through clothing without fear of stigmatization. However, after her experience in graduate school, she found herself shopping for clothing which was “more conservative and professional,” even enlisting the help of friends for whom she felt reflected a more conservative and professional style. P7 did not want her clothing to be another reason for her advisors to see her as unprofessional.

P7: I love clothing! I have kind of a crazy style. I…love bizarre stuff like eyeball necklaces, and shirts that say “puke” or have aliens all over them. I have always dressed more alternatively. I think, in general, clothing is…important for how you express yourself, how you are perceived by other people, especially in a professional context. I think that is something that I have tried to utilize to overcome [my disabilities]. If I could look good and be professional in appearance, that will help me be taken more seriously and that would remove…barriers I have. I don’t have the same luxury as others do in how they dress. In general, I think that’s just how it is, that having a disability, we don’t have the same luxuries. And, clothing is definitely another one of those ways in which…you express yourself in a professional manner.

On the other hand, for five of the 12 study participants (42%), clothing played a different role, one which reflected the need to be seen as attractive and even “sexy,” as was described by P10. P10, a retired bank executive currently working as a patient advocate and living with MS, discussed how, after her colon surgery, she needed to accommodate her colostomy bag, so she looked for adaptive clothing. Her self-efficacy was low, and her sense of style suffered in order to accommodate her disability. However, after her self-efficacy increased, following a change in careers and an accommodating supervisor, her relationship with clothing changed. She then saw clothing as a reflection of her new opportunities. She stated that she looked for clothing which made her feel more attractive, “sexy”, and comfortable. She began to “venture out” and look for clothing like she had never worn before.

P10: At this stage…I am looking for [something] that makes me feel attractive and that I can be comfortable in. I used to wear pantyhose all the time and didn’t wear dresses too much because I was getting over the stigma of my colostomy bag. So, my cousin helped me venture out and took me to shop at Kato’s and I found full bottom tops that flowed out and worked. Now I am a dress person. I’d say three out of five days you will see me in a dress. Clothing now makes me feel important and sexy.

The study participants demonstrated the importance of clothing to PLWD. They are no different than any other consumer looking for clothing which expresses their sense of style. These participants provide insight into research which focuses on the role clothing plays for PLWD and their ability to fully participate in society. As seen in Figure 1, the study participants navigate their workplace participation goals, stigma, and self-efficacy with their clothing. Lack of appropriate clothing exacerbates their stigma even further, while, when appropriate clothing is found, their self-efficacy is enhanced tremendously. Enhanced self-efficacy is supported by the literature which suggests that appropriate clothing helps improve workplace participation among PLWD [5,34] while recognizing the diverse goals and reasons for their workplace participation, and, therefore, diverse options of appropriate clothing are necessary for them.

4. Conclusions

It is suggested that PLWD continue to face barriers to societal participation, including workplace participation, yet our understanding of the depth and breadth of these barriers has been limited. In particular, the role of clothing as a barrier to workplace participation has been little explored in the literature. To address the gap in our understanding, this study was designed to explore the issues concerning social participation for PLWD, particularly, their workplace participation. In addition, the role of stigma, self-efficacy, and clothing in workplace participation was investigated through a qualitative exploration of their experiences. The study provides results which show two main themes, as described by the study participants. First, they want to participate in the workplace because, while disability itself limits opportunities, work in general defines their identities and allows them extra social opportunities. At the same time, because of their disability, they experience both public and self-stigma, both of which question their self-efficacy. However, when they have appropriately professional clothing, their self-efficacy is enhanced, and their self-stigma is decreased.

4.1. Contributions to the Literature

These findings provide a few key contributions to the literature. First, as the study participants shared, clothing plays a significant role in the life fulfilment and workplace participation of PLWD. Particularly, the emphasis on social capital built via workplace participation must be noted because nine out of 12 participants (75%) shared that social capital helps build a higher level of meaning for work and that work helps them feel more accepted by society, despite their disability. For them, work means more than just a means to support themselves, it is a demonstration of how they can contribute to the greater good of society and be seen as a role model for other PLWD. Schur [7] and Araten-Bergman and Stein [14] suggested that social capital is a critical factor for PLWD to overcome the marginalization they face and that social capital provides new opportunities to fully participate in society. Social capital as a factor to overcome marginalization demonstrates a continued need for efforts to support the integration of PLWD into local communities and to provide meaningful work opportunities for PLWD. For this to happen, there is a need for clothing companies to offer appropriate clothing that PLWD could use and adapt to different social and professional situations, additionally highlighting the critical role of clothing in this study.

The second contribution of this study is for policy makers, the community, or even the public. The study findings highlight the idea that not only is disability itself serving as a barrier to PLWD’s workplace participation, their appearance, usually created and managed by clothing, creates an additional barrier to their social participation. This suggests that, perhaps, the concept of work must be understood beyond what is addressed in the ADA, which specifies reasonable workplace accommodations in physical built environment settings. Interestingly, none of the study participants discussed physical barriers in their built environments. Rather, they discussed feeling incapable of achieving more because of the public or social stigma that employers may possess over them, and such stigma is usually created and intensified by their clothing or appearance. Therefore, the study findings show the gap between the physical barriers addressed by the ADA and the societal barriers created by self- and others’ perceptions through the lack of appropriate clothing for PLWD. Therefore, the study clarifies the need for diverse options of appropriate clothing for PLWD designed with the disability and fashion in mind, or clothing that is inclusively designed to support the non-disabled and disabled alike. Therefore, additional research is needed to develop more robust societal supports for PLWD, including clothing, which would help eliminate social barriers to their workplace participation. Such research could be a significant addition to advancing and improving current ADA policies.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the study findings show specific needs for appropriate clothing expressed by PLWD. As was found in this study, PLWD wish to find clothing that reflects their style, status, and professional identity. They have different goals for workplace participation and therefore different needs for different clothing. Therefore, clothing cannot be just functional. It should also include styles and attractiveness that will enhance the wearers’ self-confidence and communicate their self-identities. Currently, all study participants shared that they are unable to find appropriate clothing, which often discourages them to participate in the workplace and makes them feel inadequate. Some study participants discussed the need to “hide” behind clothing as a means of being accepted, while others discussed clothing as a means to build confidence and allow for credibility in the workplace, an opportunity to move beyond their disability. Therefore, the study findings show opportunities for clothing industry leaders to learn and guide their efforts to produce inclusively designed, or more fashion-forward adaptive clothing for a diverse PLWD community. The same holds true for apparel educators. The study findings demonstrate the need to include an emphasis on PLWD as a viable target market for consideration in clothing design and distribution.

4.2. Limitations of the Research

Despite the important contributions, the study has some limitations and therefore offers future research opportunities. The barriers faced by PLWD are vast, and although the study demonstrated how PLWD can overcome barriers to workplace participation through self-efficacy and clothing, it is necessary to continue investigating the relationship between stigma, self-efficacy, and clothing in workplace participation among PLWD. Because of the small sample size and the reliance on participant stories, it is necessary to expand the sample size to include a more diverse population of PLWD, so to gain a deeper understanding of the barriers facing PLWD and of how stigma, self-efficacy, and clothing impact those barriers. This could be further impacted by the small regional background of the participants. Future research should include populations from both small regional areas and large cities. This would help discover any regional, urban–rural, population diversity issues or workplace differences based on population location. Therefore, any generalization of this research must be cautiously considered because of the regional location of the participants. Further research is suggested to further recognize PWLD’s diverse set of challenges and barriers to social and workplace participation.

Acknowledgments

This study received no funding. The costs associated with publishing this article as open access was provided through researcher funds.

Author Contributions

Kerri McBee-Black and Jung Ha-Brookshire conceived and designed the research study; Kerri McBee-Black conducted the interviews; Kerri McBee-Black and Jung Ha-Brookshire analyzed the data; Kerri McBee-Black and Jung Ha-Brookshire wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Erickson, W.; Lee, C.; von Schrader, S. 2014 Disability Status Report: United States; Cornell University Yang Tan Institute on Employment and Disability: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.disabilitystatistics.org/StatusReports/2014-PDF/2014-StatusReport_US.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Brault, M.W. Disability among the Working Population: 2008 and 2009; American Community Survey Briefs; ACSBR/09-12; United States Census Bureau, 2010; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/acsbr09-12.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Haegele, J.A.; Hodge, S. Disability Discourse: Overview and Critiques of the Medical and Social Models. Quest 2016, 68, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T.; Watson, N. The Social Model of Disability: An Outdated Ideology? In Research in Social Science and Disability; Emerald (MCB UP): Bingley, UK, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabel, A.; McBee-Black, K.; Dimka, J. Apparel-Related Participation Barriers: Ability, Adaptation and Engagement. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Larson, J.E.; Rüsch, N. Self-Stigma and the “Why Try” Effect: Impact on Life Goals and Evidence-Based Practices. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schur, L. The Difference a Job Makes: The Effects of Employment among People with Disabilities. J. Econ. Issues 2002, 36, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabel, A.; Dimka, J.; McBee-Black, K. Clothing-Related Barriers Experienced by People with Mobility Disabilities and Impairments. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 59, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, C.M.; Kaiser, S.B.; Wingate, S.B. Perceptions of Functional Clothing by Persons with Physical Disabilities: A Social-Cognitive Framework. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1985, 4, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liskey-Fitzwater, N.; Moore, C.L.; Gurel, L.M. Clothing Importance and Self-Perception of Female Adolescents with and without Scoliosis. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1993, 11, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.G. Clothing and Physical Impairment: Join Effects on Person Perception. Home Econ. Res. J. 1982, 10, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.E.; Kincade, D.H. Inclusive Design in Apparel Product Development for Working Women with Physical Disabilities. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2007, 35, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. The Psychology of Working: A New Perspective for Career Development, Counseling, and Public Policy; Counseling and Psychotherapy; Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Araten-Bergman, T.; Stein, M.A. Employment, Social Capital, and Community Participation among Israelis with Disabilities. Work 2014, 48, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R.D.; Autin, K.L.; Bott, E.M. Work Volition and Job Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Work Meaning and Person-Environment Fit. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadyl, J.K.; McPherson, K.M. Understanding Decisions about Work after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2010, 20, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, S. Public Stigma in Intellectual Disability: Do Direct versus Indirect Questions Make a Difference? J. Intell. Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, Y.-C.; Lien, Y.-J.; Chang, H.-A.; Wang, S.-C.; Tzeng, N.-S.; Loh, C.-H. Evidence for the Indirect Effects of Perceived Public Stigma on Psychosocial Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Self-Stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 240, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of Personal Agency through the Self-Efficacy Mechanism. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Schwarzer, R., Ed.; Hemisphere Publishing Corp: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W. Self-Efficacy in a Relational World: Social Cognitive Mechanisms of Adaptation and Development. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Douglas, S.P. Diversity in Product Symbolism: The Case of Female Executive Clothing. Psychol. Mark. 1987, 4, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, K. Adaptive Clothing—Preserves Independence and Assists the Caregiver. Lippincott’s Case Manag. 2001, 6, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.C.; Olaso, J.; Gil, M.; Puigcerver, S.; Dura, J.V.; Lopez, I. FASHION-ABLE: Needs and Requirements for Clothing, Footwear and Orthotics of Consumers Groups with Highly Individualised Needs. In Proceedings of the 2012 18th International ICE Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE), Munich, Germany, 18–20 June 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.M. Disability and the Social Importance of Appearance. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2001, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J.; Jacoby, J. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.T. A Typology of Mixed Methods Sampling Designs in Social Science Research. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 281–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A. Strategies for Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, N.L.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. An Array of Qualitative Data Analysis Tools: A Call for Data Analysis Triangulation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2007, 22, 557–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wingate, S.B.; Kaiser, S.B.; Freeman, C.M. Salience of Disability Cues in Functional Clothing: A Multidimensional Approach. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1986, 4, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).