Abstract

Children of imprisoned parents have a two times greater risk of health problems, including difficulties in their environment, academic and behavioural problems as well as social stigma. Focusing on children who have parents in prison has not been a priority for research. This review aims to describe current knowledge on children who have imprisoned parents in a global context and highlight areas for additional research. This review highlights the coping strategies that children of imprisoned parents use and explores interventions that exist to support children of imprisoned parents. This review employed a qualitative narrative synthesis. The database search yielded 1989 articles, of which 11 met inclusion and quality criteria. Stigmatizing children due to parental imprisonment was a widespread problem. Children’s coping strategies included maintaining distance from the imprisoned parent, normalizing the parent’s situation and taking better control over their lives through distraction, sports, supportive people and therapy. Children received the best support in school-based interventions or mentoring programmes. The overall low quality of the included studies indicates a need for further research.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, the increasing number of parents in prison has led to a growing public health concern about their children who are left behind. Children must cope with the separation from their parent and often struggle with several situations, such as insecurity due to their new living conditions, stigmatization in school and an increased risk of poverty due to no income from the incarcerated parent [1]. In the United States (US) alone, approximately five million children had experienced parental incarceration in 2012, which reflects seven percent of all US children nationwide [2]. The number of US children who had an imprisoned father increased five-fold between 1980 and 2000, while the estimates for imprisoned mothers doubled between 1991 and 2007 [2]. In Europe, approximately 800,000 children had experienced parental imprisonment in 2013 [3]. These estimates indicate a growing public health problem.

A large study that was conducted in Denmark on children and their parents in prison [4] found that these children were at risk of social exclusion due to the stigma related to parental imprisonment and that they were punished because they did not participate in social activities [4]. Compared to children of parents who had no history of imprisonment, children who had a parent in prison had more mental health problems [4] and psychosocial stress [5] due to the separation from their parents, loneliness, stigmatization, labile childcare agreements and uncertain home and school environments. Lee et al. [6] investigated the correlation between parental imprisonment and children’s physical and psychological health based on data from a national longitudinal study. The results showed that there was a significant correlation between parental imprisonment and health difficulties, such as asthma, migraines, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety. A comparative study in four European countries [3] found that children who had parents in prison had an increased risk of mental health problems, especially when children were older than eleven years. The relationship between parents and their children is one of the most important social circumstances in children´s lives. Normally, this relationship is built up through orderliness, family contact and stability, encouraging children´s physical and psychological health and well-being [7]. When facing the experience of parental imprisonment, children can meet several difficulties such as loss of family safety and stability, stigma and different stress factors due to the shift in the social determinants of their lives [7]. Parental imprisonment can be challenging and life-changing for the left-behind families, even though the children are innocent and often unaware of the parental situation [8]. It is very different from child to child as to how parental imprisonment affects them and how they experience this situation. Furthermore, there are differences based on the relationship to the parent and the background of the imprisonment, and if it is something that happens often or not [8]. Furthermore, the parental background affects the children´s experience of parental imprisonment. Almost seven out of ten imprisoned parents have a history of substance dependence or abuse. Six out of ten imprisoned parents suffer from a mental health problem, whereas less than 50 percent have ever received treatment for it [9].

Research indicates that children of imprisoned parents have a higher risk of future incarceration [10]. Inside the criminal justice system, the rights of children who have imprisoned parents are often unclear, as there are few written rules [1]. Children are at risk of being left behind because there are insufficient social welfare services, deficits in laws and policies, uncertainties about how to work with these children and insufficient protections for those who live in prison with their parents [1]. One challenge is the stigma of parental imprisonment. Children who fear stigmatization attempt to manage alone without telling anybody about their situation [8].

There are some differences at country level and in how the penal systems work. It is shown that lower penalties, a good penal regime, a functional welfare system and an unprejudiced public attitude are helpful for the children of imprisoned parents [10]. In Sweden, for example, children can better handle the situation of stigma than in the United Kingdom (UK), mainly because of the welfare state system, better penal system rules and the very open and tolerant attitude in general society [10]. The type and length of the sentences, visiting rights and the kind of available support varies between the different countries. Additionally, in the US, there are differences between jails and prisons [9]. Some jails have strict rules regarding visitations. Plexiglas and telephone-based communications create a feeling of non-contact. In the prisons, on the other hand, parental prisoners are mostly allowed to have physical contact with their children [9].

Parental imprisonment can have different effects on their children, especially differed by maternal or paternal imprisonment. A few studies investigated maternal imprisonment and found disruption of the mother–child relationship as well as social, emotional and physical problems in their children [11,12]. Furthermore, maternal imprisonment involves practical, economic and social changes for the affected families. Children can get affected through movements from their homes and unstable care agreements. In general, maternal imprisonment is very stressful for the affected children, with a high incidence of mental health problems [11,12]. On the other hand, paternal imprisonment seems to affect the children in a more emotional way. Boswell et al. [13] describe anxiety and anger, deep feelings of loss and aggression as some of the main problems connected to paternal imprisonment. Often, the children kept their father’s imprisonment as a secret from their peers. When fathers get imprisoned, the child´s mother is the caregiver in 90% of the affected families. However, when mothers go to prison, fathers are the caregivers for the left-behind children in only 28–31% of the cases and, often, the grandmother becomes the primary caregiver for the affected children instead [14].

Children’s reactions to parental imprisonment can also differ by gender. Murray and Farrington [15] found that 71% of the investigated boys who had experience with parental imprisonment in their childhood, showed antisocial behaviors at age 32 compared to boys without this experience [15]. Both boys and girls react to parental imprisonment, but boys are more likely to express their feelings and thoughts in an externalized way, leading to behavioral problems and problems of aggression. On the other hand, girls cope in an internalize way [14]. However, there are some differences in the general coping strategies related to the different age groups of children [16]. Preschool children want to obtain help primarily from their caregivers, react immediately with anger in difficult situations, use distracting activities or disengage in some situations. Children in school use more cognitive mechanisms, as well as problem-solving and distraction [16]. When comparing children in school with preschool children, it is noticeable that the children in school choose various support strategies. Besides that, the school children’s coping mechanisms are varied between behavioral- and cognitive-handling strategies. Positive and future-focused thinking and behavior seem to help children (with parents in prison) in school [16]. The need for policies and interventions for children of imprisoned parents led to the development of the COPING project [3]. This project analysed the mental health, experiences of stigma, social exclusion, isolation, well-being and resilience of children and the needs for policies and programmes in four participating countries: the UK, Germany, Romania and Sweden [3]. The findings showed that children primarily talked to others (such as friends, caregivers, or NGO and school staff members) as a coping strategy. The study suggested that schools may provide important emotional and pedagogical support for children who have parents in prison.

ICF International [17] performed a randomized-controlled trial of the “Amachi Texas program” between 2008 and 2010 to investigate the effects of “one-to-one mentoring” on children’s school performance, social competence, behaviours, future thoughts and family relationships [17]. After six months, children who participated in the programme had significant improvements in family relationships and feelings of self-worth. Evaluations at 12 and 18 months after the program, showed that children who had a mentor, had better outcomes for social contacts, community and school connection compared to the control group [17]. The “Children of Promise” project in New York provides after school activities and summer camps for children of imprisoned parents, which results in increased intellectual, social and emotional capacities [18].

In general, the focus on children of imprisoned parents has not been a priority in research, and little is known about the effects of parental imprisonment on children [10]. A few studies have investigated the effects of parental imprisonment, but research has not examined children’s coping processes [5]. For example, Murray and Farrington [19] concluded that key areas for further research are the children’s experiences of trauma due to parental imprisonment, the effectiveness of public programmes and interventions, children’s financial safety and challenges related to stigma.

This study aimed to describe current research on children of imprisoned parents in a global context and highlight areas for additional research. The questions that guided this review were as follows: What are the coping strategies that are used by children with imprisoned parents? What interventions exist to support children of imprisoned parents?

2. Coping Theories

There are several different theories and definitions of coping. Compas and colleagues [20] divide coping into three control strategies: Primary control is defined as “coping that is intended to influence objective events or conditions”. People can achieve individual control over circumstances and their reactions and feelings, including problem solving abilities as well as emotional expression and regulation. Secondary control has a purpose “of increasing one’s personal adaptation to present circumstances and the environment, including cognitive restructuring, a positive attitude and distraction”. The third strategy encompasses relinquished control and includes wishful thinking and denial and is characterized by a lack of coping. Self-regulation and individual motivation have been identified as crucial for attaining primary or secondary control [20].

Antonovsky, one of the main founders of the salutogenetic mindset [21], defines coping strategies as “.... an overall plan of action for overcoming stressors” [22]. Antonovsky suggests that people are constantly exposed to stressors. These stressors include different situations with internal or external demands in which people have difficulties finding a solution or an automatic adaptive response: they need to cope or may develop an illness. Antonovsky found that some people stayed healthy despite crises and stressors and that there were differences in ways of dealing with stressors [23]. These people had a commonality, which he named a “Sense of Coherence” (SOC) [22]. People who perceive different circumstances and the world as comprehensive, manageable and meaningful are able to cope with stressors and rarely experience them as a threat, which is primarily due to trust in their own capability to act successfully [23]. Having a strong SOC indicates that people are motivated to cope in a situation in which problems are understandable and the person can manage the stressor with the best available individual resources [21]. A strong SOC is constructed through peoples’ life experiences and different resistance resources as for example parents and friends and a safe environment [22].

Antonovsky stated the importance of seeing the human being in a holistic way. Thus, based on Antonovky’s thinking, the term “coping” in this study includes coping strategies, coping skills and coping mechanisms as well as handling strategies, adaptation toward a difficult situation, and managing and dealing with various situations.

Antonovsky’s theory is a resource-oriented approach on peoples’ abilities and much more than a simple measurement of the sense of coherence. Thus, it fits in the analysis of coping and well-being of people in all age categories in many settings [24]. Moreover, there is a convincing evidence base showing that the salutogenesis approach is a robust theory validated and widely applied in explaining how people may maintain their health and well-being despite the stressors in life [25].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

This study was conducted and based on the guidelines for a systematic review that included qualitative and quantitative as well as mixed methods research [26,27]. However, for feasibility reasons, such as time constrains, the present review was intended to be a preliminary re-inventory preceding a full systematic review. Thus, we were inspired by the scoping review process described by Levac et al. [28] as it aims to map the research area of interest in a rapid way. The aim of a systematic review is to identify, evaluate and interpret the best current available evidence, e.g., [26,27,29]. The review process in the present study, however differed from the conventional review types, by conducting an analytical qualitative reinterpretation of the literature [28,29]. The aim of the review was to examine the extent, range and nature of a research area, to determine the value of conducting a full systematic review and to summarize and disseminate research findings as well as to identify a lack of existing research [29]. A pre-defined strategy was used to search the existing literature and analyse the data to answer the predefined research questions [26]. To ensure transparency and the quality of the review, the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) checklist was applied at the end of the review process [24].

3.2. Search Strategies and Sources

The search took place from January through March 2016 and included the following databases: Academic Search Premier, ASSIA, Cinahl, Cochrane, Embase, Global Health, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Studies were also manually searched by skimming the reference lists of relevant papers. The search terms that were used for this study included “children”, “parents”, “coping”, and “prison”. These four key terms were separately searched in each database because there were several synonyms for the terms across the different databases. At the end, a combined search with the four keywords was conducted in each database. Truncation wildcards* were used for most of the base terms that had multiple endings. For example, the term coping* resulted in studies on coping skills, coping strategies and coping mechanisms. For each search strategy, synonyms were identified using the webpage “www.thesaurus.com”. Cinahl headings, MeSH and alternative spellings that were linked to Boolean, were used. At the end, each category was connected with the Boolean AND to complete the final search.

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included based on the following criteria: the publications were written in English, Danish, Swedish, German and/or Norwegian; they were dealing with parental imprisonment, the duration of which was more than one night; the study focus was 6–17-year-old children with biological, adoptive or step-parents.

The research question that examined coping used the following inclusion criteria: coping strategies from the children’s perspectives and primary research. The second part of the research question used the following additional inclusion criteria: existing interventions aimed at children of imprisoned parents as well as the use of primary and secondary literature.

The additional criteria for inclusion were that children themselves reported their experiences and not the parents. After reviewing the studies, the authors found that research with children younger than 6 years old often relied on parental reports. The maximum age of 17 years was chosen to include children below the age of majority [30]. To obtain a general and global overview, this review did not examine time, country limitations or type of study design or methods. Moreover, the study selection process did not differentiate between males/females. As such, all studies were considered regardless of gender to avoid excluding good quality results and papers.

3.4. Search Outcomes

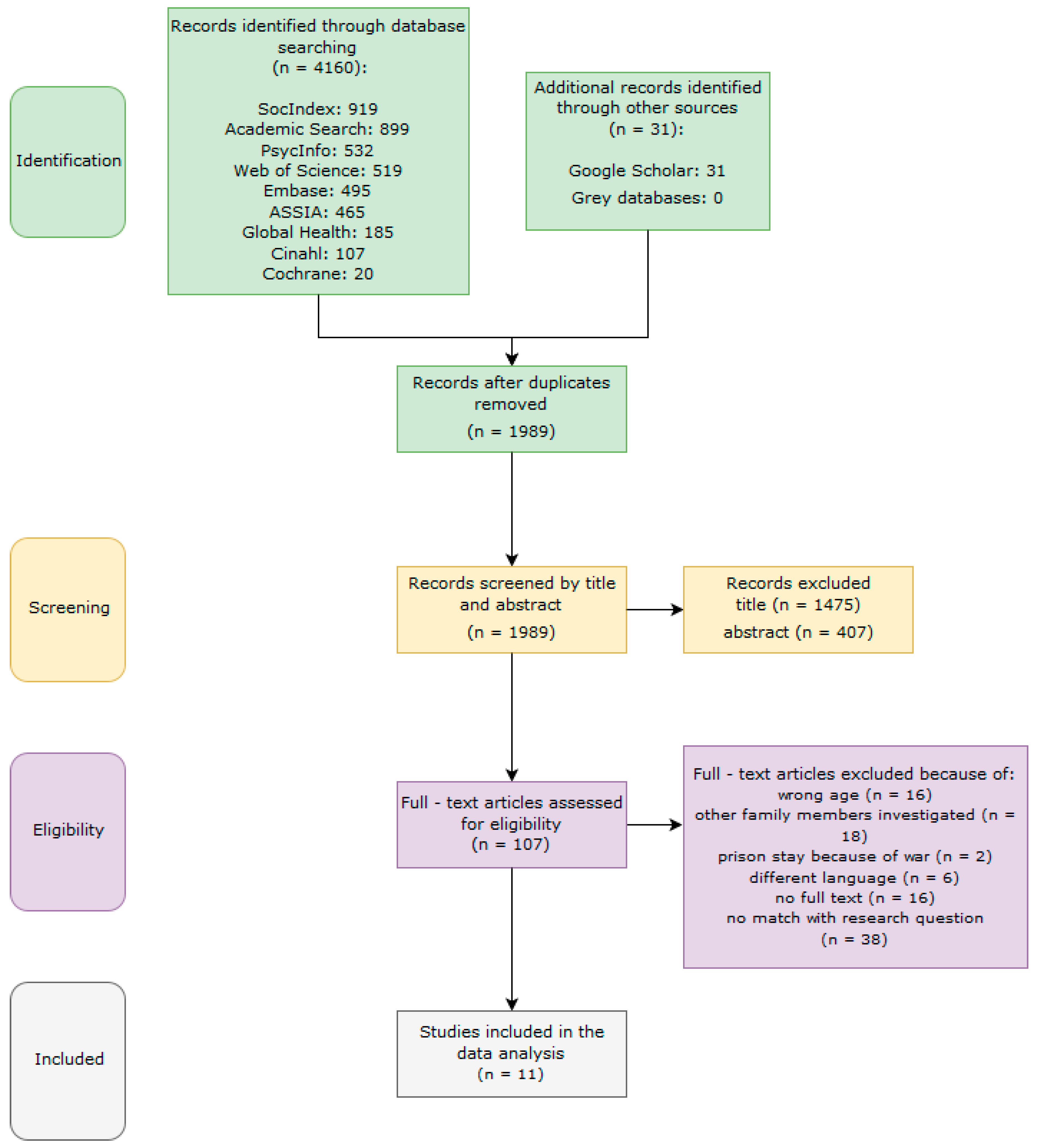

As shown in Figure 1, of the 4160 studies that were identified from the different databases, 2171 citations were removed due to duplication. In total, 1989 studies were screened for inclusion. A total of 1475 studies were removed because of their titles, 407 were removed due to their abstracts. After reading the full text from 107 studies, 80 were not relevant for the research questions and 16 were not available as full text. In total, 11 of the 107 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. From the 11 articles, five were eligible for the first part of the research question—coping—and six studies were found to be eligible for the second part of the research question—interventions. The further data extraction and illustration of the results, as well as the discussion part is divided into the two parts of the research question—coping and interventions.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

3.5. Quality Assessment

The 11 included studies were evaluated with the “Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool” (MMAT) [31,32], which is applicable for rating different study designs, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research. The primary MMAT quality criteria were reviewed for each publication based on the overall filtering questions. Then, the specific quality criteria were applied. Each study was rated with a quality score of 25%, 50%, 75% or 100%, and a higher score indicated better quality. Moreover, this review contained one literature review for the second part of the research question. In this context, the MMAT could not be used as a tool for quality assessment. Therefore, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence—instrument for reviews [33]—was used to assess the quality of one publication [34]. In this review, two studies were of low quality (25%: [35,36]), five studies had moderate scores (50%: [37,38,39,40,41]), two studies were of high quality (75%: [42,43]) and one study had very high quality (100%: [44]). The literature review [34] did not meet three-fifths of the quality criteria due to missing information. There were few scores of 75–100% due to missing information. Even though several studies had low quality, all 11 studies that met the eligibility criteria were included in this review because they contained useful information [45].

3.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

A predesigned data extraction form was used that extracted and listed information from all included studies. The data extraction form was inspired by the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews [26]. The data extraction was performed by one reviewer who was not blinded to the authors or journals during data extraction. The extraction forms reported characteristics that were related to the most important information for the two research questions. The data extraction forms were divided into two tables for the two research questions: coping and interventions.

The data synthesis extracted the included studies in tabulated form. The tables were used to structure, combine and illustrate differences and affinities among the included studies. In this review, the included studies were heterogeneous, therefore, we used a qualitative narrative synthesis [46].

4. Results

In general, the included publications in this review had heterogeneous characteristics. First, the sample size differed in the included publications, and ranged from 10 to 250 participants. Most of the studies only included a small number of children. All included publications generated information on children who were between 6 and 17 years old. Consequently, the publications included children in school as well as teenagers and adolescents who were younger than 18 years old. Of the 11 studies, eight studies only examined children, while three studies also included their caregivers [35,36,37]. Most of the studies were conducted in the US (n = 8) and Europe (n = 3). Six of the studies were qualitative [37,38,39,43,44], two used mixed methods [36,40], one was a literature review [34] and there were two quantitative studies that used convenience [35] and case-control study designs [41].

4.1. Coping Strategies

Children of imprisoned parents used several coping strategies (Table 1). Some of these strategies were described as creative when children identified that different individual activities helped them cope. Furthermore, coping strategies were resourceful, such that children found successful ways to address parental imprisonment [39,42]. Other coping strategies tended to be ineffective when children had difficulties coping with parental imprisonment and lacked social support from their environments [40]. Children primarily used a combination of strategies, which included distraction (strength through control) through school [38,39,44], participating in sports, going to the theatre, relying on their faith [38,42], spending time with friends [38,39,42] and talking to supportive people, such as family members, caregivers, friends and school professionals [38,42,44]. Therapy was effective [38,44] as was attending an NGO programme that included health professionals [39]. Keeping parental imprisonment a secret, avoiding talking about parental imprisonment, lying about the situation (de-identification) or minimizing the situation (desensitization) [40,44], fearing stigma and isolation were problems that decreased children’s coping abilities [39,40,42,44].

Table 1.

Data extraction for coping.

4.2. Interventions

Three of the included publications [34,36,43] suggested that school counsellors and health professionals could provide support for children who have parent(s) in prison (Table 2). However, there is a need to further train these professionals to perform supportive tasks. Moreover, the results indicated that mentoring programmes [35,37] increased positive attitudes and a sense of well-being while improving school performance. Positive outcomes that resulted from enrolling in a mentoring programme included better self-confidence, improved social skills, increased trust towards mentors, improved learning skills (such as concentration and motivation in school) and experiences of well-being, which led to positive coping abilities and increased self-esteem among the participating children [37]. These positive outcomes for children were also consistent with outcomes from family-based programmes [34].

Table 2.

Data extraction for interventions.

Overall, the most promising interventions were based on earlier evidence and existing behavioural theories or earlier research on children who had imprisoned parents. These interventions were successful in helping children cope [35,41].

5. Discussion

5.1. Coping

This review found that there was variability and individual multidimensional use of coping mechanisms among children who had a parent in prison. The coping strategies were dependent on the age of the child and their relationships with their imprisoned family members.

As mentioned in the findings of Jakobsen and Scharff Smith [8], children reacted and handled the imprisonment of their parent differently based on their relationship to their parents and the individual circumstances in their lives. These findings are consistent with the different results of the included studies [38,40,42]. The variety of coping strategies can partly be explained through the different compositions of the sample in terms of age and the participant’s relationships to their imprisoned family members and to what extent coping was a central focus in the included studies. Additionally, the results indicate that children cope very different, in individual ways. In general, the publications in this review showed no differences in children’s coping strategies between different age groups. The included studies primarily investigated children who were between 10 and 17 years old and were not able to draw statistically significant conclusions for younger or older groups of children.

Only two of the included studies in this review regarding to coping [38,40] investigated the importance of different age groups and supported the theoretical findings of Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck [16]. This decreases the external validity of the present review. Because children react differently based on their age and development, it is important to consider the differences in their ages [20] when drawing conclusions on the findings of this review.

The results suggest that coping strategies often include a combination of de-identification, desensitization and strength through control, as well as distracting activities and support from peers and school professionals [42,44]. These studies had higher quality scores, of 75% and 100%, compared to the findings from the other publications and are more reliable for this review.

This review reflects Compas et al.’s [20] coping theory in which coping strategies can be primary (problem solving and emotional expression and regulation) or secondary (cognitive restructuring, a positive attitude, approval and distractions). This review found that some children used avoidance, while others used engagement (desensitization and strength through control) [42,44] as primary and secondary control strategies. This tends to provide children better coping abilities because they have more control and SOC in their lives. Consistent with Antonovsky, the stressor is then viewed as something that is controllable and manageable [21].

These conclusions lead to increased external validity of the present review because the high-quality score of 100% supports the results from previous research.

Antonovsky stated that the importance of a holistic view of health and the human being could be viewed through people’s life contexts. This perspective accounts for both environmental factors and individual circumstances [47]. This approach was reflected and supported by most of the included studies that emphasized the importance of social support for children [38,39,42]. Social circumstances were essential protective factors for helping children to cope with a challenging situation, such as parental imprisonment. Strength, control and the SOC could be improved when caregivers are viewed as role models and when children can trust (for example, at school) that people will provide support.

In general, children who had better outcomes for coping strategies had good and solid family backgrounds (Antonovsky explains these as general resistance factors). Some of the children who used primary control strategies [44] or secondary comprehensibility [39,42] had a better understanding of the situation of parental imprisonment and could better manage the situation. Through distraction, support from friends and family members, and help in therapeutic sessions or mentoring, children managed the difficult experience of parental imprisonment. With the help of individual resistance resources [22], it is likely that the children who managed their situation had a strong SOC. Schools and social circumstances had a significant role in strengthening children’s resilience because they individually developed their coping abilities and resilience processes and were influenced by the environment in which they lived. Thus, children are dependent on role models, such as caregivers, teachers and peers and settings in their environment, such as schools. All these factors impact children’s SOC.

Furthermore, the results indicate that children’s coping strategies were similar for parental incarceration and parental HIV, which was shown by Tisdall et al. [48]. Some participants received support from schools and social support groups, others maintained the parental issue as a secret, while others were open to talking, coping and obtaining support for the situation [48]. In addition, Jakobsen and Scharff Smith [8] and Murray et al. [5] claimed that children were afraid of being stigmatized and tried to address challenging situations alone without telling anybody. These findings were consistent with the results from the included publications in this review [38,39,40,42,44]. The problems of stigma and isolation were described in all the included studies and the results of this review showed that children with imprisoned parents were often afraid of being bullied or stigmatized [38,39,40,42,44]. It became evident that stigma and bullying may lead to social exclusion; however, this was not well described in the included studies. Stigmatization and bullying can also result in negative attitudes from other students’ parents as well as unpleasant experiences in school. A lack of school policies for bullying or discrimination can worsen the situation.

One consistent finding from this review was that children were open to discuss their parent’s imprisonment. Children who have imprisoned parents often wanted to know the truth about the situation, regardless of whether it is a disease or imprisonment [38,40,48,49]. Involvement and open discussion about the parent’s situation appeared to improve children’s coping.

Karlsson [10] stated that children in Sweden might have better coping strategies for stigma because there is a well-developed welfare state system. This review did not support this claim and showed no significant differences across the different countries. Coping strategies were similar in Europe [39,40] and in the US [40,42,44]. However, the results from the European studies supported the idea of being open about parental imprisonment and talking about parental imprisonment with someone (e.g., NGOs devoted to this issue), as presented by Karlsson [10]. To provide more valid and generalized conclusions would require more data from different countries with developing problems and with hard penal systems.

5.2. Interventions

Group interventions for children who were having similar experiences appeared to lead to more reflection on the parental situation and children’s coping strategies, as well as disclosing their parental situation to others. In general, group interventions had positive long-term effects [34,41,43]. In contrast, mentoring programmes supported children’s coping strategies through distractive activities and helped children to immediately feel better [17,35,37]. One of the main findings from this review indicated that schools have a significant role in guiding and supporting children who have imprisoned parents. The present review found that schools are very resourceful and helpful for children’s academic and personal improvement. However, there is a need for additional staff training and guidelines for working with children who have a parent in prison and the resulting situations [36,43], which was also stated in Tisdall et al.’s [48] findings.

The quality scores for school-based support and counselling ranged from 25% to 75%, which indicates that these findings are less reliable because of the different results and quality scores. However, in general, the results are supported by the findings from ICF international [17] and the COPING project [3]. Furthermore, problems were detected in identifying the children who had the highest need for intervention among children who suffer from stigma and bullying. Some studies randomly chose affected children [37].

The qualitative [37] and quantitative [35] results from this review for mentoring programmes are consistent with ICF international’s [17] findings, in which there were improvements in children’s social outcomes, such as stability, cognitive development, greater openness and more self-confidence. A common conclusion from the publications in this review is the need for stable and solid evidence-based interventions [19,35,37].

Aside from Miller [34], the interventions that were included in this review did not differ in the target age groups. The intervention programmes were for all children. However, children’s need for help might differ across age groups. Thus, it is within reason to believe that interventions would benefit from the consideration of age (and gender).

5.3. Limitations

The results from the present review were consistent with previous research. However, this study has several limitations that should be addressed. This review only included publications for which the author had electronic access. In the inclusion and exclusion process, relevant studies may have been overlooked based on this limited access. The intention of this review was to include peer reviewed and Grey literature to reduce bias, but only two Grey databases were searched: GreyNet and Greylit. Including more unpublished studies could reduce the risk of publication bias.

Only one reviewer identified the keywords, synonyms and conducted the search and study selection processes through reading titles and abstracts, which increases the risk of publication and reporting bias. Including another reviewer may have improved the identification of studies. The lack of blinding of the author may have biased the assessment of the review, as the knowledge of the results from the individual publications might have impacted the method and analysis.

The methodology of the review was descriptive [28,29,50] and, consequently there were no statistical analyses to assess the overall effects of the interventions. Due to heterogeneity in the included studies, a qualitative approach was the most appropriate method. It is important to discuss the lack of confounding variables and mediators in this review. Circumstances, such as gender, age, the home environment, abuse and parental violence could affect the results for coping and the available interventions, but these variables were not described in the included studies. It might be that boys and girls need different specific interventions based on their gender, because they possibly cope and experience feelings and emotions differently. Therefore, further research should take into account this aspect and explore deeper the gender differences in the coping mechanisms. In the majority of the included studies, the father was the one who was incarcerated. The results of this review might have been different if the data had included more studies about children with an imprisoned mother. The comparison is possibly not feasible because some studies considered only imprisoned fathers and others focused on both genders.

Furthermore, factors such as country and the prior relationship to the imprisoned parents might have affected the coping strategies of the children in diverse ways and led to difficulties in comparing the children´s coping abilities. Whether the used coping strategies differed according to differences in how much the parental imprisonment affected the individual children can be discussed. This could have led to an overestimation of the results in this review. Children may also have been in the process of puberty or suffered from other problems in addition to parental imprisonment and, in some cases, would need other types of interventions. When synonyms for the keyword “coping” were used, throughout full text reading of the included studies, the keyword “resilience” was also found. Therefore, using the word “resilience” could possibly have generated more hits.

The results from this review were based on small sample sizes, which decreases generalizability and external validity. It is difficult to draw conclusions for a larger population based on these small sample sizes because the results may be due to coincidence. Furthermore, most of the conclusions in the review were based on qualitative interviews at one point in time. Subjective qualitative measurements at only one time point can be biased because respondents’ answers, or the narratives may depend on mood, time of day and other circumstances that could affect their feelings and perceptions. A longitudinal study with follow-ups and a large sample size would have provided more effective and valid results for this review. Furthermore, this review shows a lack of good quality research, which is consistent with newer research [2,38,44], pointing out that there is a need for further research.

6. Conclusions

The results indicated heterogeneity in the included studies across several multidimensional and individual coping strategies, such as de-identification, desensitization and strength through control. Furthermore, children adopted consistent strategies, including having supportive people as well as talking openly about the situation with staff in their schools. Distracting activities and support from NGO’s programmes were also important for coping. A consistent finding throughout the included studies was the stigmatization of children who had a parent in prison.

Children obtained support from school professionals and group sessions or were able to participate in mentoring programmes as well as social activities to obtain help with academic and behavioural performance. Mentoring programmes consistently had positive outcomes. High-functioning interventions were based on evidence, previous theories and results on children of imprisoned parents and included support from professionals who had experience working with children of imprisoned parents.

This review can assist researchers in studying further this topic, and increase interest and awareness of this public health problem to protect children of imprisoned parents from short- and long-term negative impacts. Additional public health investigations should educate the public and formulate specific policies that address the problems of stigma and isolation.

Furthermore, criminal justice services should develop a common evidence-based data collection and monitoring system to develop policies and provide supportive tools for children of imprisoned parents. It is important to have international guidelines for the estimated numbers of affected children.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Penal Reform International. Children of Incarcerated Parents. Available online: http://www.penalreform.org/priorities/justice-for-children/what-were-doing/children-incarcerated-parents/ (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. A Shared Sentence: The Devastating Toll of Parental Incarceration on Kids, Families and Communities. Policy Report. 2016. Available online: http://aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-asharedsentence-2016.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Jones, A.D.; Gallagher, B.; Manby, M.; Robertson, O.; Schützwohl, M.; Berman, A.H.; Hirschfield, A.; Ayre, L.; Urban, M.; Sharrah, K. COPING Final, Children of Prisoners. Interventions and Mitigations to Strengthen Mental Health, 2013. Available online: http://childrenofprisoners.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/COPINGFinal.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Oldrup, H.; Frederiksen, S.; Henze-Pedersen, S.; Olsen, R.F. Indsat Far- Udsat Barn? Hverdagsliv og Trivsel Blandt Børn af Fængslede. Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd, 2016. Available online: https://pure.sfi.dk/ws/files/473564/1617_Indsat_far_udsat_barn.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P.; Sekol, I. Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2012, 138, 175–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.D.; Fang, X.; Luo, F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1188–e1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Masi, M.E.; Teuten Bohn, C.; Benson, D.B. Children with Incarcerated Parents. A Journey of Children, Caregivers and Parents in New York State; Council on Children and Families: Rensselaer, NY, USA, 2010.

- Jakobsen, J.; Scharff Smith, P. Børn af Fængslede-en Informations- og Undervisningsbog, 1st ed.; Narayana Press: Gylling, Danmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shlafer, R.J.; Gerrity, E.; Ruhland, E.; Wheeler, M. Considering children’s outcomes in the context of complex family experiences. Child. Mental Health Rev. 2013, 1–17. Available online: http://www.extension.umn.edu/family/cyfc/our-programs/ereview/docs/June2013ereview.pdf (accessed on 23. May 2017).

- Karlsson, R. Vad Sager Forskningen om Barn Till Fängslade Föräldrar. En Forskningsöversikt; RiksBryggan: Karlstad, Sweden, 2007; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, A.; Flynn, C. Supporting imprisoned mothers and their children: A call for evidence. Probat. J. 2013, 60, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, H. The strains of maternal imprisonment: Importation and deprivation stressors for women and children. J. Crim. Justice 2012, 40, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, G.; Wedge, P.; Kingsley, J. Imprisoned Fathers and Their Children; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Parke, R.D.; Clarke-Stewart, C.A. From Prison to Home: The Effect of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families, and Communities. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/effects-parental-incarceration-young-children (accessed on 25 April 2017).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life-course. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.A.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. The Development of Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICF International. Mentoring Children Affected by Incarceration: An Evaluation of the Amachi Texas Program. Available online: http://docplayer.net/6592271-Mentoring-children-affected-by-incarceration-an-evaluation-of-the-amachi-texas-program.html (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Children of Promise, NYC. Our Programs. Available online: http://www.cpnyc.org/about-us/ (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Evidence-based programs for children of prisoners. Criminol. Public Policy 2006, 5, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress and Coping. New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.K.; Johnsen, T.J. Sundhedsfremme i Teori og Praksis, 2nd ed.; Forlaget Philosophia: Aarhus, Danmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. In The Sense of Coherence in the Salutogenic Model of Health; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Sagy, S.; Eriksson, M.; Bauer, G.F.; Pelikan, J.M.; Lindström, B.; Espnes, G.A. The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer Open: Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10, ISSN 978-3-319-04600-6. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert, M.; Hannes, K.; Maes, B.; Onghena, P. Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2013, 7, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkers, M. What is a scoping review? KT Update 2015, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Dictionaries. Child. Available online: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/child (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Pluye, P.; Robert, E.; Cargo, M.; Bartlett, G.; O’Cathain, A.; Griffiths, F.; Boardman, F.; Gagnon, M.P.; Rousseau, M.C. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews, 2011. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/84371689/MMAT%202011%20criteria%20and%20tutorial%202011-06-29updated2014.08.21.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Appendix B. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg6b/chapter/appendix%20b:%20methodology%20checklist:%20systematic%20reviews%20and%20meta-analyses (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Miller, K.M. The impact of parental incarceration on children: An emerging need for effective interventions. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2006, 23, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruster, B.E.; Foreman, K. Mentoring children of prisoners: Program evaluation. Soc. Work Public Health 2012, 27, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikes, B. The role of schools in assisting children and young people with a parent in prison—Findings from the COPING project. In Identities and Citizenship Education: Controversy, Crisis and Challenges. Selected Papers from the Fifteenth Conference of the Children’s Identity and Citizenship in Europe Academic Network; CiCe: London, UK, 2013; pp. 77–384. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, J.; Nygaard, J. Children of incarcerated parents: How a mentoring program can make a difference. Soc. Work Public Health 2012, 27, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manby, M.; Jones, A.D.; Foca, L.; Bieganski, J.; Starke, S. Children of prisoners: Exploring the impact of families’ reappraisal of the role and status of the imprisoned parent on children’s coping strategies. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2015, 18, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.; Steinhoff, R. Children’s experiences of having a parent in prison: “We look at the moon and then we feel close to each other”. Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii» Alexandru Ioan Cuza «din Iaşi. Sociologie şi Asistenţă Socială 2012, 5, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Sanderson, J.; Britner, P.A. Ambiguous loss and posttraumatic stress in school-age children of prisoners. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, D.W.; Lynch, C.; Rubin, A. Effects of a solution-focused mutual aid group for hispanic children of incarcerated parents. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2000, 17, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesmith, A.; Ruhland, E. Children of incarcerated parents: Challenges and resiliency, in their own words. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2008, 30, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Bhat, C.S. Supporting students with incarcerated parents in schools: A group intervention. J. Spec. Group Work 2007, 32, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.I.; Easterling, B.A. Coping with confinement: Adolescents’ experiences with parental incarceration. J. Adolesc. Res. 2015, 30, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Shlonsky, A. Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. 2007. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/525444systematicreviewsguide.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Antonovsky, A. Helbredets Mysterium- at Tåle Stress og Forblive Rask, 1st ed.; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, Danmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, E.K.M.; Kay, H.; Cree, V.E.; Wallace, J. Children in need? Listening to children whose parent or carer is HIV positive. Br. J. Soc. Work 2004, 34, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thastum, M.; Johansen, M.B.; Gubba, L.; Olesen, L.B.; Romer, G. Coping, social relations, and communication: A qualitative exploratory study of children of parents with cancer. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).