Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

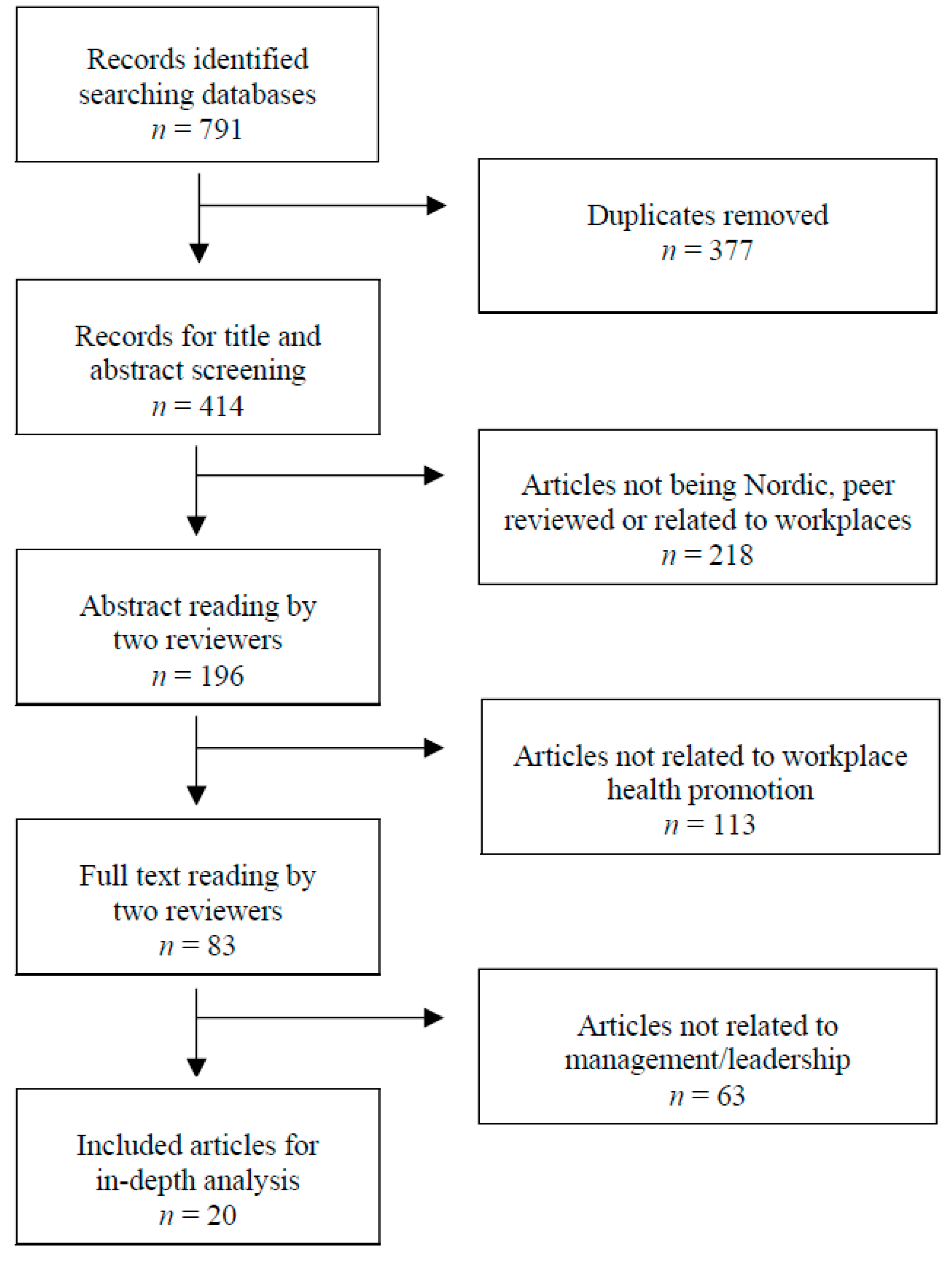

2. Materials and Methods

Analysis

3. Results

A An Explicit Whole-System Approaches to Sustain Ability

B Approaching Sustainability by Studying Success Factors for Implementation of Workplace Health Promotion

C Approaching Sustainability in the Framing of the Studies

D An Explicit Economic Focus Counteracts Sustainability

4. Discussion

Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1. Andersen, I., et al. (2010). Changing job-related burnout after intervention-a Quasi-experimental study in six human service organizations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 52(3): 318–323. |

| 2. Andruškienė, J., et al. (2011). Work experience and school workers' health evaluated by salutogenic health indicators. Acta Medica Lituanica 18(2): 86–91. |

| 3. Aura, O., et al. (2010). Strategic wellness management in finland: the first national survey of the management of employee well-being. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 52(12): 1249–1254. |

| 4. Auvinen, A.-M., et al. (2012). Workplace Health Promotion and Stakeholder Positions: A Finnish Case Study. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 67(3): 177–184. |

| 5. Averlid, G. and S. B. Axelsson (2012). Health-Promoting Collaboration in Anesthesia Nursing: A Qualitative Study of Nurse Anesthetists in Norway. AANA Journal 80(4 Suppl): S74–80. |

| 6. Backstrom, I., et al. (2014). Change of the quality management culture through health-promotion activities? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 25(11–12): 1236–1246. |

| 7. Bostrom, E., et al. (2013). Role clarity and role conflict among Swedish diabetes specialist nurses. Primary Care Diabetes 7(3): 207–212. |

| 8. Bringsén, Å., et al. (2012). Exploring workplace related health resources from a salutogenic perspective: Results from a focus group study among healthcare workers in Sweden. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 42(3): 403–414. |

| 9. Bringsén, Å., et al. (2011). Flow situations during everyday practice in a medical hospital ward. Results from a study based on experience sampling method. BMC Nursing 10(1): 1–9. |

| 10. Clays, E., et al. (2011). The perception of work stressors is related to reduced parasympathetic activity. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health 84(2): 185–191. |

| 11. Ekbladh, E., et al. (2010). Perceptions of the work environment among people with experience of long term sick leave. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 35(2): 125–136. |

| 12. Elwer, S., et al. (2010). Health against the odds: Experiences of employees in elder care from a gender perspective. Qualitative Health Research 20(9): 1202–1212. |

| 13. Eriksson, A., et al. (2010). Development of health promoting leadership—Experiences of a training programme. Health Education 110(2): 109–124. |

| 14. Eriksson, A., et al. (2011). Health promoting leadership—Different views of the concept. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 40(1): 75–84. |

| 15. Eriksson, A., et al. (2012). Collaboration in workplace health promotion—A case study. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 5(3): 181–193. |

| 16. Ervasti, J., et al. (2012). Work-Related Violence, Lifestyle, and Health Among Special Education Teachers Working in Finnish Basic Education. Journal of School Health 82(7): 336–343. |

| 17. Grönlund, A. and B. Stenbock-Hult (2014). Vårdpersonalens syn på hälsofrämjande ledarskap. [Translated from Swedish: “Nursing Personnel’s views on health-promoting leadership”]. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research & Clinical Studies/Vård i Norden 34(1): 36–41. |

| 18. Hansen, C. D. and J. H. Andersen (2009). Sick at work—A risk factor for long-term sickness absence at a later date? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 63(5): 397–402. |

| 19. Harmoinen, M., et al. (2014). Stories of management in the future by young adults and young nurses. Contemporary Nurse. |

| 20. Hasson, H., et al. (2010). Factors associated with high use of a workplace web-based stress management program in a randomized controlled intervention study. Health Education Research 25(4): 596–607. |

| 21. Hasson, H., et al. (2014). Managing implementation: roles of line managers, senior managers, and human resource professionals in an occupational health intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56(1): 58–65. |

| 22. Haukenes, I., et al. (2011). Disability pension by occupational class—The impact of work-related factors: The Hordaland Health Study Cohort. BMC Public Health 11(Suppl 4): 406–415. |

| 23. Holmgren, K., et al. (2010). The Association between Poor Organizational Climate and High Work Commitments, and Sickness Absence in a General Population of Women and Men. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 52(12): 1179–1185. |

| 24. Hope, S., et al. (2010). Associations between sleep, risk and safety climate: A study of offshore personnel on the Norwegian continental shelf. Safety Science 48(4): 469–477. |

| 25. Håkansson, C. and G. Ahlborgjr (2010). Perceptions of employment, domestic work, and leisure as predictors of health among women and men. Journal of Occupational Science 17(3): 150–157. |

| 26. Håkansson, C., et al. (2011). Associations between women's subjective perceptions of daily occupations and life satisfaction, and the role of perceived control. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 58(6): 397–404. |

| 27. Innstrand, S., et al. (2011). Exploring within- and between-gender differences in burnout: 8 different occupational groups. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health 84(7): 813–824. |

| 28. Innstrand, S. T., et al. (2010). Personal vulnerability and work-home interaction: The effect of job performance-based self-esteem on work/home conflict and facilitation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 51(6): 480–487. |

| 29. Innstrand, S. T., Langballe, E. M., Espnes, G. A., Aasland, O. G. & Falkum, E. (2010). Personal vulnerability and work-home interaction: The effect of job performance-based self-esteem on work/home conflict and facilitation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 51, 480–487. |

| 30. Innstrand, S. T., et al. (2012). A longitudinal study of the relationship between work engagement and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Stress and Health 28(1): 1–10. |

| 31. Jakobsen, K. and M. Lillefjell (2014). Factors promoting a successful return to work: from an employer and employee perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 21(1): 48–57. |

| 32. Jensen, A. G. C. (2013). Towards a parsimonious program theory of return to work intervention. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 44(2): 155–164. |

| 33. Jensen, A. G. C. (2013). A two-year follow-up on a program theory of return to work intervention. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 44(2): 165–175. |

| 34. Jensen, F. W., et al. (2011). Vocational training courses as an intervention on change of work practice among immigrant cleaners. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 54(11): 872–884. |

| 35. Jensen, J. M. (2013). Everyday life and health concepts among blue-collar female workers in Denmark: implications for health promotion aiming at reducing health inequalities. Global Health Promotion 20(2): 13–21. |

| 36. Karlqvist, L. and G. Gard (2013). Health-promoting educational interventions: A one-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 41(1): 32–42. |

| 37. Kinnunen-Amoros, M. and J. Liira (2014). Work-related Stress Management by Finnish Enterprises. Industrial Health 52(3): 216–224. |

| 38. Lallukka, T., et al. (2010). Sleep complaints in middle-aged women and men: The contribution of working conditions and work-family conflicts: Sleep in the middle-aged. Journal of Sleep Research 19(3): 466–477. |

| 39. Lamminpää, A., et al. (2012). Employee and work-related predictors for entering rehabilitation: A cohort study of civil servants. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 44(8): 669–676. |

| 40. Langballe, E. M., et al. (2011). The predictive value of individual factors, work-related factors, and work-home interaction on burnout in female and male physicians: a longitudinal study. Stress & Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 27(1): 73–87. |

| 41. Larsson, A., et al. (2012). Identifying work ability promoting factors for home care aides and assistant nurses. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 13(1). |

| 42. Larsson, J., et al. (2009). To control with health: From statistics to strategy. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 32(1): 49–57. |

| 43. Larsson, J., et al. (2011). Control charts as an early-warning system for workplace health outcomes. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 39(4): 409–425. |

| 44. Larsson, R., et al. (2014). Workplace health promotion and employee health in Swedish municipal social care organizations. Journal of Public Health 22(3): 235–244. |

| 45. Ljungblad, C., et al. (2014). Workplace health promotion and working conditions as determinants of employee health. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 7(2): 89–104. |

| 46. Midje, H. H., et al. (2014). Workaholism and Mental Health Problems among Municipal Middle Managers in Norway. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 56(10): 1042–1051. |

| 47. Nabe-Nielsen, K., et al. (2015). Does workplace health promotion reach shift workers? Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health 41(1): 84–93. |

| 48. Nielsen, K. and L. M. Pedersen (2014). What do Social Processes mean for Quality of Human Resource Practice? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 4(2): 21–45. |

| 49. Nilsson, P. (2010). Development and quality analysis of the Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS). Work—A Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 35(2): 153–161. |

| 50. Nilsson, P., et al. (2013). The Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS): A useful tool in workplace health promotion. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 45(3): 379–387. |

| 51. Nilsson, P., et al. (2011). How to make a workplace health promotion questionnaire process applicable, meaningful and sustainable. Journal of Nursing Management 19(7): 906–914. |

| 52. Nilsson, P., et al. (2012). Workplace health resources based on sense of coherence theory. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 5(3): 156–167. |

| 53. Niskanen, T., et al. (2012). An evaluation of EU legislation concerning risk assessment and preventive measures in occupational safety and health. Applied Ergonomics 43(5): 829–842. |

| 54. Norregaard, C. D., et al. (2014). Adoption of workplaces and reach of employees for a multi-faceted intervention targeting low back pain among nurses’ aides. BMC Medical Research Methodology 14. |

| 55. Odegaard, F. and P. Roos (2014). Measuring the Contribution of Workers’Health and Psychosocial Work-Environment on Production Efficiency. Production and Operations Management 23(12): 2191–2208. |

| 56. Oxenstierna, G., et al. (2011). Conflicts at Work-The Relationship with Workplace Factors, Work Characteristics and Self-rated Health. Industrial Health 49(4): 501–510. |

| 57. Palstam, A., et al. (2013). Factors promoting sustainable work in women with fibromyalgia. Disability & Rehabilitation 35(19): 1622–1629. |

| 58. Pedersen, M. S. and J. N. Arendt (2014). Bargaining for health: A case study of a collective agreement-based health program for manual workers. Journal of Health Economics 37(1): 123–136. |

| 59. Perko, K., et al. (2014). Transformational leadership and depressive symptoms among employees: Mediating factors. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 35(4): 286–304. |

| 60. Reineholm, C., et al. (2011). Evaluation of job stress models for predicting health at work. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 40(2): 229–237. |

| 61. Saaranen, T., et al. (2012). The occupational well-being of school staff and maintenance of their ability to work in Finland and Estonia S focus on the school community and professional competence. Health Education (0965-4283) 112(3): 236–255. |

| 62. Schell, E., et al. (2011). Workplace aesthetics: Impact of environments upon employee health? Work—A Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 39(3): 203–213. |

| 63. Sekine, M., et al. (2011). Sex inequalities in physical and mental functioning of British, Finnish, and Japanese civil servants: role of job demand, control and work hours. Social Science and Medicine 73(4): 595–603. |

| 64. Selander, J. and N. Buys (2010). Sickness Absence as an Indicator of Health in Sweden. International Journal of Disability Management 5(2): 40–47. |

| 65. Sirola-Karvinen, P., et al. (2010). Cocreating a health-promoting workplace. J Occup Environ Med 52(12): 1269–1272. |

| 66. Sivertsen, H., et al. (2013). The relationship between health promoting resources and work participation in a sample reporting musculoskeletal pain from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, HUNT 3, Norway. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorder 14: 100. |

| 67. Soares, M. M., et al. (2012). Effects of early support intervention on workplace ergonomics—a two-year followup study. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 41: 809–811. |

| 68. Stahl, C. and E. E. Stiwne (2014). Narratives of Sick Leave, Return to Work and Job Mobility for People with Common Mental Disorders in Sweden. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 24(3): 543–554. |

| 69. Stoetzer, U., et al. (2014). Organization, relational justice and absenteeism. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 47(4): 521–529. |

| 70. Stoetzer, U., et al. (2014). Organizational factors related to low levels of sickness absence in a representative set of Swedish companies. Work—a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation 47(2): 193–205. |

| 71. Storholmen, T. C. B., et al. (2012). Design for end-user acceptance: requirements for work clothing for fishermen in Mediterranean and northern fishing grounds. International Maritime Health 63(1): 32–39. |

| 72. Strandmark, M. and G. Rahm (2014). Development, implementation and evaluation of a process to prevent and combat workplace bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 42(15): 66–73. |

| 73. Thanem, T. (2013). More passion than the job requires? Monstrously transgressive leadership in the promotion of health at work. Leadership 9(3): 396–415. |

| 74. Torp, S., et al. (2010). How positive psychosocial work factors may promote self-efficacy and mental health among psychiatric nurses. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 12(1): 18–28. |

| 75. Torp, S., et al. (2013). Work engagement: a practical measure for workplace health promotion? Health Promotion International 28(3): 387–396. |

| 76. Torp, S., et al. (2011). Social support at work and work changes among cancer survivors in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 39(6, Suppl): 33–42. |

| 77. Torp, S., et al. (2012). Worksite adjustments and work ability among employed cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 20(9): 2149–2156. |

| 78. Torp, S., et al. (2012). Sick leave patterns among 5-year cancer survivors: A registry-based retrospective cohort study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 6(3): 315–323. |

| 79. Vinberg, S. and B. J. Landstad (2014). Workplace-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation Programs in Swedish Public Human Service Organisations. International Journal of Disability Management 9: N.PAG-00. |

| 80. Voltmer, E., et al. (2012). Job stress and job satisfaction of physicians in private practice: Comparison of German and Norwegian physicians. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 85(7): 819–828. |

| 81. Von Thiele Schwarz, U. and H. Hasson (2011). Employee self-rated productivity and objective organizational production levels: Effects of worksite health interventions involving reduced work hours and physical exercise. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 53(8): 838–844. |

| 82. Von Thiele Schwarz, U. and H. Hasson (2012). Effects of worksite health interventions involving reduced work hours and physical exercise on sickness absence costs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 54(5): 538–544. |

| 83. Vuori, J., et al. (2012). Effects of resource-building group intervention on career management and mental health in work organizations: Randomized controlled field trial. Journal of Applied Psychology 97(2): 273–286. |

References

- The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1986.

- Chu, C.; Breucker, G.; Harris, N.; Stitzel, A.; Gan, X.; Gu, X.; Dwyer, S. Health-promoting workplaces—international settings development. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.; Vainio, H. Well-being at work–overview and perspective. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 2010, 36, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgaard, R.H.; Winkel, J. Occupational musculoskeletal and mental health: Significance of rationalization and opportunities to create sustainable production systems–A systematic review. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 261–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rootman, I.; Goodstadt, M.; Hyndman, B.; McQueen, D.V.; Potvin, L.; Springett, J.; Ziglio, E. (Eds.) Evaluation in Health Promotion: Principles and Perspectives; No. 92; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. Hälsans idé [The Idea of Health]; Almqvist & Wiksell: Stockholm, Sweden, 1984. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Dooris, M. Holistic and sustainable health improvement: The contribution of the settings-based approach to health promotion. Perspect. Public Health 2009, 129, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp, S. Hva er helsefremmende arbeidsplasser—og hvordan skapes det? [What are health promoting workplaces—and how can they be created?]. Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift [J. Soc. Med.] 2013, 90, 768–779. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Dooris, M. The Settings Approach: Looking back, looking forward. In Health Promotion Settings Principles and Practice; Scriven, A., Hodgins, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G.; Vandenberg, R.J.; McGrath-Higgins, A.L.; Griffin-Blake, C.S. Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2010, 83, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENWHP. Luxembourg Declaration on workplace health promotion in the European Union. 2007. Available online: http://www.enwhp.org/fileadmin/rs-dokumente/dateien/Luxembourg_Declaration.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Eriksson, A. A Study of the Concept and Critical Conditions for Implementation and Evaluation. Ph.D. Thesis, Nordic School of Public Health, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, W.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being behaviors and style associated with the affective wellbeing of their employees? Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Neumann, W.P.; Imbeau, D.; Bigelow, P.; Pagell, M.; Wells, R. Prevention of musculoskeletal disorders within management systems: A scoping review of practices, approaches, and techniques. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 51, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelikan, J.; Schmied, H.; Dietscher, C. Improving Organizational Health: The Case of Health Promoting Hospitals. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health. A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Orvik, A. Conceptualizing Organizational Health—Public Health Management and Leadership Perspectives. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aalborg, Aalborg, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Docherty, P.; Kira, M.; Shani, A.B.R. What the world needs now is sustainable work systems. In Creating Sustainable Work Systems; Docherty, P., Kira, M., Shani, A.B.R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsen, B. Work organization and ‘the Scandinavian model’. Econ Ind Democr. 2007, 28, 650–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeids og inkluderingsdepartementet. Lov om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern mv. (arbeidsmiljøloven) [The Work Environment Act]. Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion: Oslo, Norway, 2005. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Method 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäckström, I.; Lagrosen, Y.; Eriksson, L. Change of the quality management culture through health-promotion activities? Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2014, 25, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.; Landstad, B.; Vinberg, S. To control with health: From statistics to strategy. Work 2009, 32, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, J.; Landstad, B.J.; Wiklund, H.; Vinberg, S. Control charts as an early-warning system for workplace health outcomes. Work 2011, 39, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirola-Karvinen, P.; Jurvansuu, H.; Rautio, M.; Husman, P. Cocreating a Health-Promoting Workplace. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.; Axelsson, R.; Bihari Axelsson, S. Development of health promoting leadership-experiences of a training programme. Health Educ. 2010, 110, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Axelsson, R.; Axelsson, S.B. Health promoting leadership–Different views of the concept. Work 2011, 40, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.; Bihari Axelsson, S.; Axelsson, R. Collaboration in workplace health promotion-a case study. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2012, 5, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, H.; Villaume, K.; von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Palm, K. Managing implementation: Roles of line managers, senior managers, and human resource professionals in an occupational health intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, R.; Ljungblad, C.; Sandmark, H.; Åkerlind, I. Workplace health promotion and employee health in Swedish municipal social care organizations. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungblad, C.; Granström, F.; Dellve, L.; Åkerlind, I. Workplace health promotion and working conditions as determinants of employee health. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2014, 7, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Pedersen, L.M. What do Social Processes mean for Quality of Human Resource Practice? Nord. J. Working Life Stud. 2014, 4, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, T.; Naumanen, P.; Hirvonen, M.L. An evaluation of EU legislation concerning risk assessment and preventive measures in occupational safety and health. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinberg, S.; Landstad, B.J. Workplace-based prevention and rehabilitation programs in Swedish public human service organisations. Int. J. Disabil. Manag. 2014, 9, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aura, O.; Ahonen, G.; Ilmarinen, J. Strategic wellness management in Finland: The first national survey of the management of employee well-being. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen-Amoros, M.; Liira, J. Work-related Stress Management by Finnish Enterprises. Ind. Health 2014, 52, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, K.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T. Transformational leadership and depressive symptoms among employees: Mediating factors. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoetzer, U.; Åborg, C.; Johansson, G.; Svartengren, M. Organization, relational justice and absenteeism. Work 2014, 47, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoetzer, U.; Bergman, P.; Åborg, C.; Johansson, G.; Ahlberg, G.; Parmsund, M.; Svartengren, M. Organizational factors related to low levels of sickness absence in a representative set of Swedish companies. Work 2014, 47, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grönlund, A.; Stenbock-Hult, B. Vårdpersonalens syn på hälsofrämjande ledarskap. [Translated from Swedish: “Nursing Personnel’s views on health-promoting leadership”]. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. Clin. Stud./Vård i Norden 2014, 34, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midje, H.H.; Nafstad, I.T.; Syse, J.; Torp, S. Workaholism and Mental Health Problems among Municipal Middle Managers in Norway. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dooris, M. Joining up settings for health: A valuable investment for strategic partnerships? Crit. Public Health 2004, 14, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheirer, M.A. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am. J. Eval. 2005, 26, 320–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, K. Organisational development for occupational health and safety management. In OHS Regulation for a Changing World of Work; Bluff, E., Gunningham, N., Johnstone, R., Eds.; The Federation Press: Leichhardt, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swerissen, H.; Crisp, B.R. The sustainability of health promotion interventions for different levels of social organization. Health Promot. Inter. 2004, 19, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, K.; Faragher, B.; Cooper, C.L. Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömgren, M.; Eriksson, A.; Bergman, D.; Dellve, L. Social capital among healthcare professionals: A prospective study of its importance for job satisfaction, work engagement and engagement in clinical improvements. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellve, L.; Eriksson, A. Health-promoting managerial work: A theoretical framework for a leadership program that supports knowledge and capability to craft sustainable work practices in daily practice and during organizational change. Societies 2017, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Included articles | Categories | Countries | Method | Management/Leadership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aura, O., et al. (2010). | C | Finland | Quantitative survey | Management |

| Backstrom, I., et al. (2014). | A, C | Sweden | Quantitative survey | Leadership |

| Eriksson, A., et al. (2010). | B | Sweden | Qualitative case study | Management, leadership |

| Eriksson, A., et al. (2011). | B | Sweden | Qualitative interview | Management, leadership |

| Eriksson, A., et al. (2012). | B, C | Sweden | Qualitative case study | Management, leadership |

| Gronlund, A. & B. Stenbock-Hult (2014). | C,D | Finland | Qualitative interviews | Mainly leadership |

| Hasson, H., et al. (2014) | B | Sweden | Qualitative interviews | Management, leadership |

| Kinnunen-Amoros, M. & J. Liira (2014) | C | Finland | Quantitative survey | Management |

| Larsson, J., et al. (2009). | A, B, C | Sweden | Interventions | Mainly management |

| Larsson, J., et al. (2011). | A, B, C, D | Sweden, Norway | Interventions | Management, leadership |

| Larsson, R., et al. (2014). | B, C | Sweden | Quantitative survey | Mainly management |

| Ljungblad, C., et al. (2014). | B,C | Sweden | Quantitative survey | Mainly management |

| Midje, H. H., et al. (2014). | C | Norway | Quantitative survey | Mainly management |

| Nielsen, K. & L. M. Pedersen (2014). | B, C, D | Denmark | Qualitative interviews & Quantitative survey | Mainly management |

| Niskanen, T., et al. (2012). | B, C | Finland | Quantitative survey | Management |

| Perko, K., et al. (2014). | C | Finland | Quantitative survey | Leadership |

| Sirola-Karvinen, P., et al. (2010). | A, C | Finland | Intervention study | Management |

| Stoetzer, U., et al. (2014a). | C | Sweden | Qualitative interviews | Mainly leadership |

| Stoetzer, U., et al. (2014b). | C | Sweden | Qualitative interviews | Mainly leadership |

| Vinberg, S. & B.J. Landstad (2014). | B, C | Sweden, Norway | Qualitative interviews, Document analysis & Quantitative survey | Mainly management |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eriksson, A.; Orvik, A.; Strandmark, M.; Nordsteien, A.; Torp, S. Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review. Societies 2017, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020014

Eriksson A, Orvik A, Strandmark M, Nordsteien A, Torp S. Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review. Societies. 2017; 7(2):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleEriksson, Andrea, Arne Orvik, Margaretha Strandmark, Anita Nordsteien, and Steffen Torp. 2017. "Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review" Societies 7, no. 2: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020014

APA StyleEriksson, A., Orvik, A., Strandmark, M., Nordsteien, A., & Torp, S. (2017). Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review. Societies, 7(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020014