Health-Promoting Managerial Work: A Theoretical Framework for a Leadership Program that Supports Knowledge and Capability to Craft Sustainable Work Practices in Daily Practice and During Organizational Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim and Disposition

2. Development of a Theoretical Framework and Leadership Program

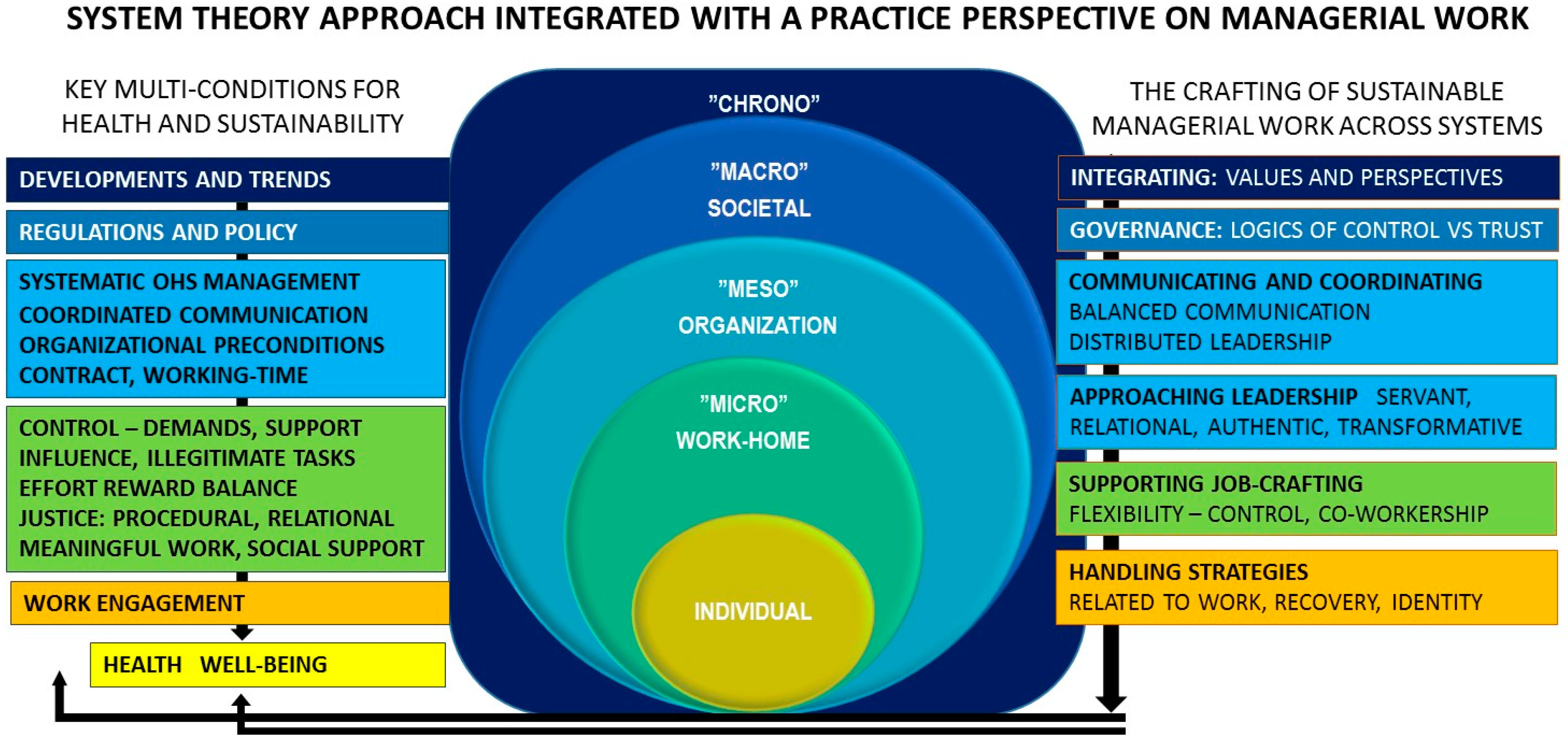

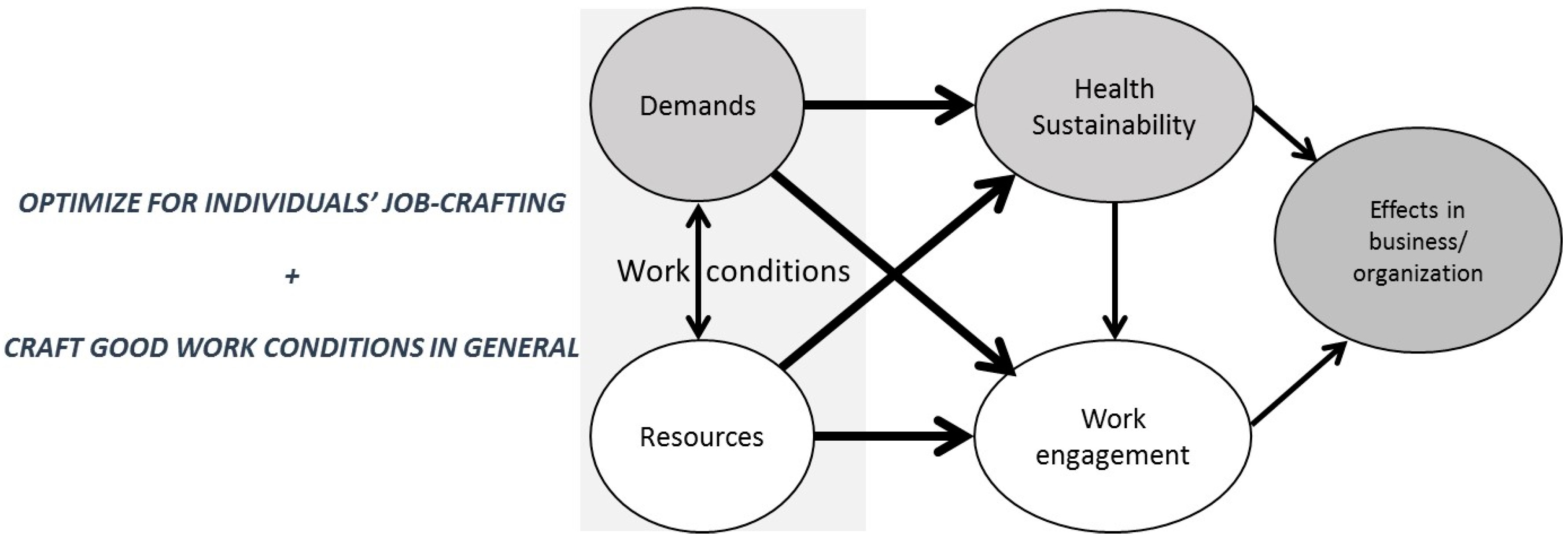

3. System Theory Approach Integrated with a Practice Perspective on Managerial Work

3.1. The Model

Key Conditions and Managerial Work that are Bridging across System Levels

3.2. Pedagogical Principles and Measures for Crafting Integrated Handling over System Levels

- Take action from available individual and organizational resources: Increase awareness, support integrated knowledge, and act from available resources by (a) observing, identifying, acknowledging, delimiting and/or reducing risks and obstacles, and (b) supporting resources [76,77]. Resources at the individual level comprise using experiences, awareness, and handling strategies to shift between helicopter and close-up perspectives. At the group level, these comprise the group climate, communication, and social capital. Organization-level resources may include basic structures for OHS, organizational values, norms, communication, and governance.

- Learn a model of dialog: Improve interactions, reflections, sharing, and practical applications of knowledge through dialog from the principles of balanced communication [62].

- Improve the likelihood of change: Meet in shared understanding of the “why” and the vision of desired improvements, through continuous communication, and a stepwise change approach that supports assessment, continuous information, and supportive leadership [78]. Improving the likelihood of change also requires a practice-serving focus that supports engagement, authentic communication, and meta-learning over organizational levels for clever applications and adjustments to practice [35,59,60].

4. An Intervention Study Based on the Theoretical Framework

4.1. Method: Form, Participants and Evaluation of Intervention Study

4.2. Summarized Results from Evaluation

“Through reflections and discussions, I have become more conscious on my way of leading and how it can have consequences on employee health.”

“Learnings from the leadership program include structures in health-promoting work. You can find a structure, you can use a structure with health promotion, not just small pieces here and there like fitness measures, but more a holistic view of how we can work [with health promotion].”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollitt, C.; Bouckaert, G. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis; New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arbetsmiljöverket. Arbetsmiljöstatistik Rapport [In English: Report of Work Environment Statistics]; Arbetsmiljöverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SBU. Arbetsmiljöns Betydelse för Symtom på Depression och Utmattningssyndrom [In English: The Importance of the Work Environment for Depression Symptoms and Burnout]; SBU: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vingård, E. En kunskapssammanställning: Psykisk Ohälsa, Arbetsliv och Sjukfrånvaro [In English: A Knowledge Review: Mental Ill Health, Working Life and Sick Leave]; FORTE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Bruinvels, D.; Frings-Dresen, M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, R.; Cockburn, W.; Irastorza, X.; Houtman, I.; Bakhuys Roozeboom, M. European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks Managing Safety and Health at Work; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Esener, European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Orvik, A.; Axelsson, R. Organizational health in health organizations: Towards a conceptualization. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgaard, R.H.; Winkel, J. Occupational musculoskeletal and mental health: Significance of rationalization and opportunities to create sustainable production systems—A systematic review. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 261–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kira, M.; van Eijnatten, F.M. Socially Sustainable Work Organizations: Conceptual Contributions and Worldviews. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K. Beyond motivation: Job and work design for development, health, ambidexterity, and more. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, W.; Guzman, J. Are leaders well-being behaviors and style associated with the affective wellbeing of their employees? Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, K.; Teed, M.; Kelley, E. The psychosocial environment: Towards an agenda for research. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2008, 1, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellve, L.; Skagert, K.; Vilhelmsson, R. Leadership in workplace health promotion projects: 1- and 2-year effect on long-term work attendance. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hammig, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schütte, S.; Chastang, J.F.; Malard, L.; Parent-Thirion, A.; Vermeylen, G.; Niedhammer, I. Psychosocial working conditions and psychological well-being among employees in 34 European countries. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 87, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, K.; Hensing, G.; Dellve, L. The association between poor organizational climate and high work commitments, and sickness absence in a general population of women and men. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellve, L.; Wikström, E. Managing complex workplace stress in health care organisations: Leaders’ perceived legitimacy conflicts. J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, E.; Dellve, L. Contemporary Leadership in Healthcare Organizations: Fragmented or Concurrent Leadership and Desired Support. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2009, 23, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, L.; Pousette, A.; Dellve, L. Span of control and the significance for public sector managers’ job demands: A multilevel study. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2013, 35, 455–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. In Measuring Environment across the Life Span: Emerging Methods and Concepts; Friedman, S., Wachs, T., Eds.; American Psychological Association Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon, P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl. Ergon. 2006, 37, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Syme, S.L. Epidemiology of health and illness: A socio-psycho-physiological perspective. In The Sage Handbook of Health Psychology; SAGE Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bone, K.D. The Bioecological Model: Applications in holistic workplace well-being management. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2015, 8, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengblad, S. (Ed.) The Work of Managers, towards a Practice Theory of Management; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tengblad, S. Management Practice—The doing of management. In the Oxford Handbook of Management (Chapter 16); Wilkinson, A., Armstrong, S.J., Lounsbury, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson-Zetterquist, U.; Müllern, U.; Styhre, A. Organization Theory: A Practice-Based Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.; Axelsson, R.; Bihari Axelsson, S. Development of health promoting leadership-experiences of a training programme. Health Educ. 2010, 110, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Skagert, K.; Dellve, L. Utveckling av Hälsofrämjande Ledarskap och Medarbetarskap [Development of Health Promoting Leadership and Employeeship]; Socialmed Tidskrift: Solna, Sweden, 2013; Volume 90. [Google Scholar]

- Arman, R.; Wikström, E.; Tengelin, E.; Dellve, L. Work activities and stress among managers in health care. In The Work of Managers; Tengblad, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Skagert, K.; Dellve, L.; Eklöf, M.; Ljung, T.; Pousette, A.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. Leadership and stress in public human service organizations: Acting shock absorber and sustaining own integrity. Appl. Ergon. 2008, 39, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skagert, K.; Dellve, L.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. A prospective study of managers’ turnover and health in a healthcare organization. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellve, L.; Jacobsson, C.; Wramsten, W.M. Open, transparent management and the media: The managers’ perspectives. J. Hosp. Adm. 2017, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Suddaby, R.; Leca, B. Institutional work: Refocusing institutional studies of organization. J. Manag. Inq. 2011, 20, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, S.R.; Kunda, G. Bringing work back in. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellve, L.; Andreasson, J.; Eriksson, A.; Strömgren, M.; Williamsson, A. Nyorientering av Svensk Sjukvård: Verksamhetstjänande Implementeringslogiker Bygger mer Hållbart Engagemang och Utveckling—I Praktiken. [Re-Orientation of Swedish Healthcare: Servant and Practice Oriented Management Approaches Builds Sustainable Engagement and Developments]; TRITA-STH-PUB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. En Teori om Organisering. [In English: A Theory on Organizing]; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson, J.; Eriksson, A.; Dellve, L. Health care managers’ views on and approaches to implementing models for improving care processes. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellve, L.; Andreasson, J.; Jutengren, G. Hur kan Stödresurser Understödja Hållbart Ledarskap Bland Chefer i Vården? [In English: How Can Support Resources Aid Sustainable Leadership among Managers in Health Care?]; Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift: Solna, Sweden, 2013; Volume 90, pp. 6–877. [Google Scholar]

- Kira, M.; van Eijnatten, F.M.; Balkin, D.B. Crafting sustainable work: Development of personal resources. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2010, 23, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unravelling the Mystery of Health, How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H.; Love, G.D. Positive health: Connecting well-being with biology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordenfelt, L. Quality of Life, Health and Happiness; Avebury: Arlington, VA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, K.T.; Todres, L. Kinds of well-being: A conceptual framework that provides direction for caring. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing 2011, 6, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, P.; Vainio, H. Well-being at work—Overview and perspective. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout and engagement. Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhadi, N.; Drach-Zahavy, A. Promoting patient care: Work engagement as a mediator between ward service climate and patient-centred care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E. Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 45, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, P. Enhance your Workplace. A Dialogue Tool for Workplace Promotion with a Salutogenic Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lund, Lund, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tengelin, E.; Arman, R.; Wikström, E.; Dellve, L. Regulating time commitments in healthcare organizations—Managers’ boundary approaches at work and in life. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2011, 25, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengelin, E. Creating Proactive Boundary Awareness—Observations and Feedback on Lower Level Health Care Managers’ Time Commitments and Stress. Licentiate Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ledarskap i Äldreomsorgen: Att Leda Integrerat Värdeskapande i en röra av Värden och Förutsättningar [In English: To Lead by Integrated and Value Adding Approaches in a Mess of Values and Pre-Conditions]; Dellve, L.; Wolmesjö, M. (Eds.) Vetenskap för Profession; Univeristy of Borås: Borås, Sweden, 2016; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Strömgren, M.; Eriksson, A.; Bergman, D.; Dellve, L. Social capital among healthcare professionals: A prospective study of its importance for job satisfaction, work engagement and engagement in clinical improvements. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellve, L.; Skagert, K.; Eklöf, M. The impact of systematic health & safety management for occupational disorders and work ability. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dellve, L.; Fallman, S.L.; Ahlstrom, L. Return to work from long-term sick leave: A six-year prospective study of the importance of adjustment latitudes at work and home. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K. Job insecurity and health: The moderating role of workplace control. Stress Med. 1996, 12, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Weber, T.J. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada, M.; Heaphy, E. The role of positivity and connectivity in the performance of business teams: A nonlinear dynamics model. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 740–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H. High Performance Healthcare: Using the Power of Relationships to Achieve Quality, Efficiency and Resilience; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom, B. Trust: Forms, Foundations, Functions, Failures and Figures; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bell´e, N. Experimental evidence on the relationship between public service motivation and job performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsing, D.; Drago-Severson, E.; Kegan, R.; Portnow, K.; Popp, N.; Broderick, M. Three Different Types of Change. Focus Basics 2001, 5, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.; Holden, R.J.; Williamsson, A.; Dellve, L. A Case Study of Three Swedish Hospitals’ Strategies for Implementing Lean Production. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2016, 6, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, K.E.; Lysø, I.H.; deMarrais, K. Evaluating executive leadership programs: A theory of change approach. ADHR 2011, 13, 208–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enos, M.D.; Kehrhahn, M.T.; Bell, A. Informal learning and the transfer of learning: How managers develop proficiency. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2003, 14, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. Educating the Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Birchall, D.; Williams, S.; Vrasidas, C. Developing design principles for an e-learning programme for SME managers to support accelerated learning at the workplace. JWL 2005, 17, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, M. Routine-generating and regenerative workplace learning. Vocat. Learn. 2010, 3, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L. Uncertainty, innovation and dynamic sustainable development. SSPP 2005, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Trader-Leigh, K.E. Case study: Identifying resistance in managing change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2002, 15, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.S. Resources in emerging structures and processes of change. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todnem By, R. Organisational change management: A critical review. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, R.; Warren, N.; Robertson, M.; Faghri, P.; Cherniack, M. Workplace health protection and promotion through participatory ergonomics: An integrated approach. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklöf, M.; Pousette, A.; Dellve, L.; Skagert, K.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. Gothenburg Manager Stress Inventory (GMSI); [In English: Gothenburg Manager Stress Inventory (GMSI)]; Institutet för Stressmedicin: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.; Dellve, L.; Strömgren, M.; Edström Bard, E. Utveckling av Hållbart och Hälsofrämjande Ledarskap—I Vardag och Förändring. Utvärdering av Interaktiv Metodik för Företagshälsovårdsdrivna Interventioner. [In English: Development of Sustainable and Health-Promotiong Leadership—In Daily Practice and during Organizational Change]; TRITA-STH-PUB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ovretveit, J. Evaluating Health Interventions: An Introduction to Evaluation of Health Treatments, Services, Policies and Organizational Interventions; McGraw-Hill International: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tynjälä, P.; Häkkinen, P. E-learning at work: Theoretical underpinnings and pedagogical challenges. JWL 2005, 17, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, E.; Ekholm, B.; Ellström, P.-E. Two types of learning environment: Enabling and constraining a study of care work. JWL 2008, 20, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.B.; Diniz, J.A.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J. Towards an Intelligent Learning Management System under Blended Learning: Trends, Profiles and Modelling Perspectives. In Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Kacprzyk, J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; Kazdin, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

| Analysis of Needs of Program Interventions |  | Pedagogical Principles of Program |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence-based knowledge on the most important factors for employee health as well as leadership strategies for improving employee health |  |

|

| Managers’ need for support in leadership role |  |

|

| Managers’ need for support in implementing and adapting program knowledge into their operative context |  |

|

| Participants | Number and Type of Workplace/Business |

|---|---|

| 19 first-line managers and key actors (e.g., safety representatives and headmen) | 10 workplaces in a county council, majority hospital units |

| 15 first-line managers and key actors (e.g., safety representatives and headmen) | 8 workplaces in a county council, majority hospital units |

| 6 first-line managers and coordinators | 3 workplaces within dental care |

| 9 second-line managers and key actors from a sector management group | 1 business area within elder care in a municipality |

| 5 second-line managers | Varying medical businesses within a county council |

| 10 first-line and one second-line manager in a management group | 10 workplaces at a hospital, all administrative units |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dellve, L.; Eriksson, A. Health-Promoting Managerial Work: A Theoretical Framework for a Leadership Program that Supports Knowledge and Capability to Craft Sustainable Work Practices in Daily Practice and During Organizational Change. Societies 2017, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020012

Dellve L, Eriksson A. Health-Promoting Managerial Work: A Theoretical Framework for a Leadership Program that Supports Knowledge and Capability to Craft Sustainable Work Practices in Daily Practice and During Organizational Change. Societies. 2017; 7(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleDellve, Lotta, and Andrea Eriksson. 2017. "Health-Promoting Managerial Work: A Theoretical Framework for a Leadership Program that Supports Knowledge and Capability to Craft Sustainable Work Practices in Daily Practice and During Organizational Change" Societies 7, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020012

APA StyleDellve, L., & Eriksson, A. (2017). Health-Promoting Managerial Work: A Theoretical Framework for a Leadership Program that Supports Knowledge and Capability to Craft Sustainable Work Practices in Daily Practice and During Organizational Change. Societies, 7(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020012