1. Introduction

Social innovation is a complex and multifaceted concept that resists a single, universal definition [

1,

2,

3]. The term

innovation, derived from the Latin

innovatio, refers to renewal or improvement. Innovation does not necessarily imply the creation of a novel product or a technologically advanced device; rather, it may involve an enhanced process, a more efficient methodology, or an innovative organizational model. Innovations are understood as creative ideas, initiatives, and solutions that ensure the more effective, higher-quality, and sustainable functioning of organizations, the provision of services, or the production of goods. Their ultimate purpose is to help societies address pressing challenges in areas such as the environment, education, employment, culture, health, and economic development, while simultaneously achieving broader social goals [

4]. The professional and effective implementation of innovative solutions thus fosters growth, creates opportunities, enables improvements, and supports sustainable development.

Although innovation encompasses a wide range of activities, products, services, and strategies, increasing attention has recently been devoted to social innovations—those that reshape social relationships and generate tangible social impact within specific communities [

5]. This heightened focus is a response to the fact that many of today’s most pressing issues are social in nature or have profound implications for the social sphere. Among these, unemployment, population aging, and climate change are particularly prominent. Rising unemployment is often associated with higher crime rates, social exclusion, and increased prevalence of emotional and psychosomatic disorders. The aging of societies, with its attendant healthcare costs, has become an even more acute problem in the aftermath of recent crises, exerting substantial pressure on public finances. Likewise, the fight against climate change is increasingly interwoven with processes of social transformation.

Moulaert et al. [

6] emphasize that social innovations are strongly related to human condition and well-being, and their goal is to overcome social exclusion, improve the quality-of-service provision, and improve and enhance life and human well-being. Within the scholarly literature, three main approaches to social innovation can be identified: managerial, economic, and critical [

7]. Managerial and economic approaches can often overlap—for example, social enterprises focus on managerial decisions and economic sustainability at the same time. A critical approach does not always contrast strictly—it may be that an organization or researcher applies a managerial approach, but with critical reflection.

The

managerial approach conceptualizes social innovation as an organizational process analogous to business innovation yet primarily oriented toward the creation of social value rather than profit. Within this perspective, emphasis is placed on how organizations can effectively manage, design, and implement social innovation through mechanisms such as project management, strategic planning, operational efficiency, and cross-sector collaboration [

8]. Social innovation is thus regarded as an instrumental tool employed by various organizations—including management institutions, third-sector entities, and public institutions—to address social problems through the clear definition of objectives, indicators, and procedural frameworks. This approach closely aligns with the ‘instrumentalist’ conception of the social innovation paradigm, which ‘treats social innovation as a means of creating more effective, efficient, or sustainable solutions that can help address market failures, reduce public spending, etc.’ [

9]. In other words, when applying a managerial perspective, social innovation is understood primarily as a means to achieve specific outcomes, often with limited reflection on broader socio-political dynamics. Consequently, the managerial approach may oversimplify the phenomenon of social innovation by neglecting contextual factors, social conflicts, and underlying power relations. Moreover, this orientation risks framing social innovation as a short-term, project-based intervention rather than as a long-term, transformative process capable of reshaping institutions and societal structures [

10].

The

economic approach interprets social innovation through the lens of value creation, efficiency, resource allocation, and market mechanisms. From this perspective, social innovation is conceived as an investment that, through its social impact, can generate returns—often non-material in nature—in the form of enhanced efficiency, cost reduction, and community sustainability. Moreover, social innovation can be examined as a hybrid social business model that integrates a social mission with financial sustainability [

11]. In this sense, the economic approach bears conceptual resemblance to discussions in the literature on corporate social responsibility [

12]. However, the scientific literature also cautions that, when adopting an economic perspective, social innovation risks being reduced to a conventional ‘business problem’. Such a reductionist view may overlook the fact that certain social innovations do not necessarily produce measurable economic returns and may even operate at a financial loss while generating substantial social value and impact. Furthermore, this approach may lead to the commercialization of social phenomena, potentially distorting their intrinsic social objectives and transformative potential.

The

critical approach is particularly significant, as it frames social innovation as a process of ‘empowerment and political mobilization’ that is directed ‘from the bottom up’, with initiatives emerging from individuals, communities, and diverse stakeholders [

13]. The critical approach extends the analysis of social innovation beyond the question of ‘how’ it functions to include inquiries into ‘why’ it operates, ‘for whom’ it is designed, which social structures it reproduces or transforms, and what power relations underpin the discourse of innovation [

7,

14]. Proponents of this approach aim to uncover the ideological dimensions of social innovation, interrogating how innovation policies may evolve into instruments for governing citizens’ autonomy and potentially establishing new forms of domination. The critical approach aligns closely with the democratic vision of the social innovation paradigm, wherein social innovation is understood as a political process grounded in collective agency and community deliberation, capable of challenging entrenched power structures [

15]. Within this framework, the principles of social equality, democracy, and the interrogation of power relations are not peripheral concerns but constitute the core analytical and normative dimensions of social innovation research.

While definitions of social innovation vary, a synthesis of key theoretical perspectives suggests that two defining features are consistently emphasized: novelty and effectiveness. Innovations qualify as social innovations if they provide less resource-intensive, more rapid, and more efficient means of addressing social challenges [

5,

13]. Put differently, social innovations can be understood as new ideas, including products, services, and models, that respond to pressing social needs while simultaneously contributing to the resolution of both social and economic problems.

During the 1980s, societies experienced rapid urbanization, the strengthening of local communities, and, subsequently, the emergence of new management paradigms shaped by the growing importance of cooperation networks and civil society organizations. Consequently, social innovation has often been associated with the development of new management models and practices, the rise of social movements, and the expansion of community activism [

16]. One of the defining characteristics of social innovation initiatives is their foundation in social relationships and the creation of new relational models [

17].

The overarching aim of social innovation is to enhance both individual and collective well-being. Its scope is wide-ranging: from new models of social service delivery to specialized online networks; from innovative approaches to teacher training to initiatives encouraging urban residents to substitute cars with bicycles; and from the promotion of global fair-trade networks to experiments in participatory governance. More recently, the social innovation perspective has come to include not only new forms of public governance that transcend traditional institutional boundaries and actively involve citizens in addressing social and global challenges, but also the cultivation of a culture of trust and risk tolerance—conditions that are critical for fostering both scientific and technological innovation. Empirical research highlights that the domains in which social innovation has been most effectively and frequently applied include pedagogy, economics, law, social services, environmental protection, education, employment, culture, health, and sustainable development [

18] (see

Table 1).

Within this context, therapy farms, sometimes also referred to as care farms or social farming initiatives, represent a particularly significant example of social innovation in rural areas [

35,

36]. By combining agricultural activity with health, social care, and educational services, therapy farms create new forms of relationships between farmers, service users, local communities, and public institutions [

37,

38]. These initiatives exemplify the defining characteristics of social innovation: they meet pressing social needs (e.g., unemployment, social exclusion, or mental health challenges) while simultaneously fostering new models of cooperation and solidarity in rural societies. As such, therapy farms align with the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) Regulation [

39], which defines social innovation as ‘an activity that is social in both its objectives and means, in particular activities related to the creation and implementation of new ideas (related to products, services, practices, and models) that simultaneously meet social needs and create new social relationships or cooperation between public, civil society, and/or private organizations, thereby benefiting society and increasing its capacity to act’.

Existing research on therapy farming, often referred to as care farming, green care or social farming, highlights its potential to integrate agricultural practices with therapeutic, educational, and social care activities in rural environments. Broadly conceptualized within the green care framework, care farming encompasses farm-based interventions that engage participants with farm work, animals, and nature to promote psychological, social, and physical well-being, particularly in geographically underserved rural areas [

40]. This body of literature [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] has documented care farming’s capacity to support mental health and social inclusion across diverse populations (e.g., at-risk youth, individuals with psychological or physical challenges), while emphasizing the importance of farm landscapes as therapeutic settings [

45]. In parallel, work on therapeutic landscapes stresses how rurality and agricultural environments co-produce well-being and care experiences through human–animal and human–place interactions [

46], demonstrating that care farms operationalize rural spaces in ways that extend beyond traditional agricultural functions by embedding care and social support within everyday farm practices [

45]. These studies contribute to an emerging understanding of therapy/social farming as a socially innovative practice that not only addresses individual needs but also reconfigures the role of rural agricultural settings in broader socio-economic and health systems.

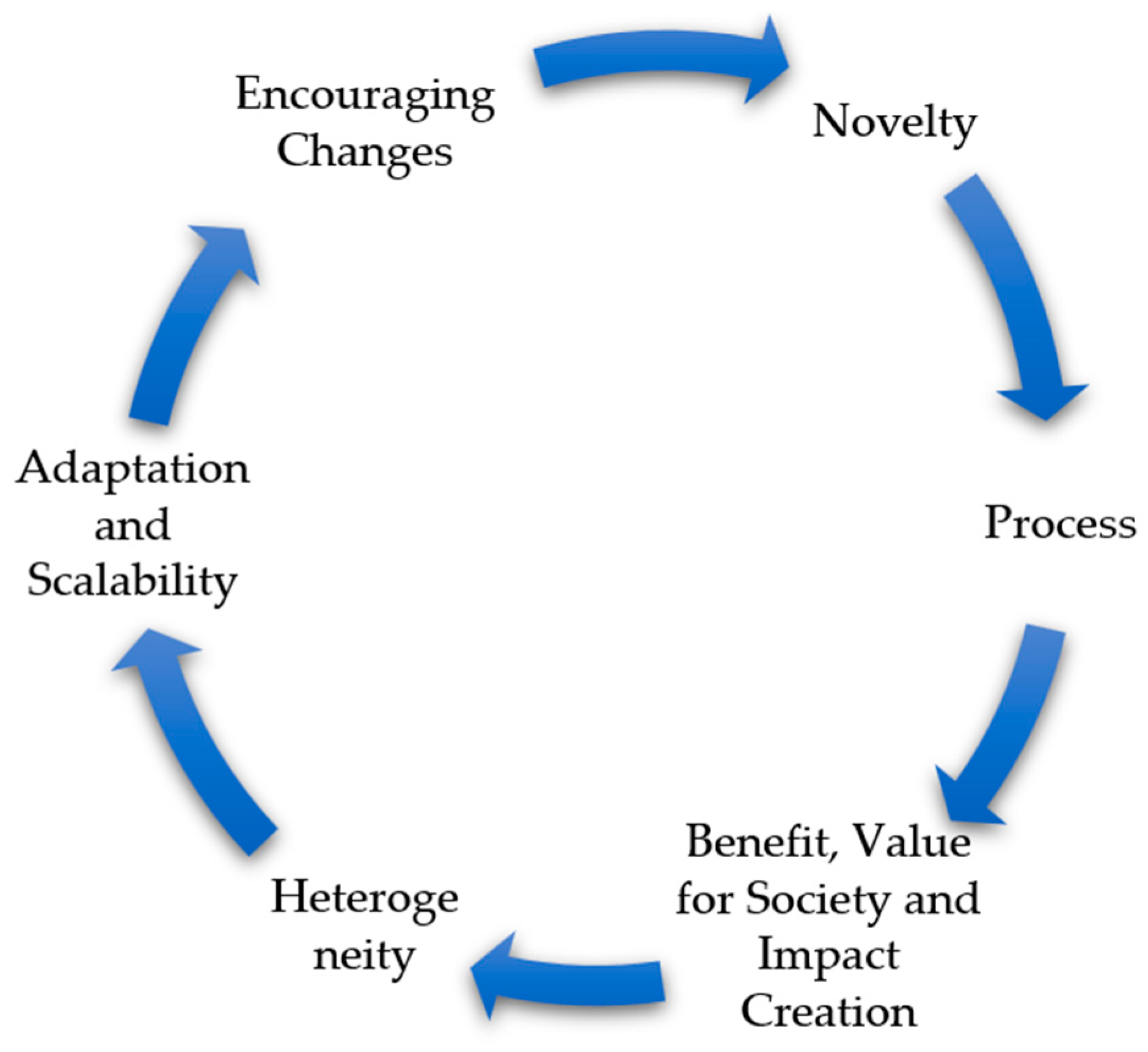

Social innovation is broadly understood as the development and implementation of new ideas—whether in the form of services, products, practices, or organizational models—that aim to meet social needs more effectively than existing solutions, while also fostering new forms of social relationships and collaborations [

5,

47]. Unlike technological or market-driven innovations, social innovations prioritize societal impact over profit, and their core function lies in creating social value by empowering communities, addressing exclusion, and enhancing well-being [

6,

48]. The process of social innovation typically unfolds through several interrelated stages: (1) novelty, where a new idea or approach emerges to address unmet or inadequately met needs; (2) process, where the innovation is developed and embedded in social practices through co-creation, experimentation, and institutional adaptation; (3) heterogeneity, reflecting the diverse actors, sectors, and knowledge systems involved; (4) benefit and impact creation, where the innovation demonstrates measurable improvements in individual and societal well-being; (5) encouraging change, as the innovation challenges existing power structures or institutional logics; and (6) adaptation and scalability, which assess the innovation’s potential to be replicated, transferred, or expanded in other contexts [

49,

50,

51]. These stages are not always linear but represent a dynamic and iterative process that responds to evolving social realities. As such, social innovation serves not only as a practical response to urgent societal challenges, but also as a transformative force that can reconfigure social systems, governance, and collective agency.

Overall, social innovation is best understood as a dynamic, non-linear process that transforms societal challenges through novel ideas and collaborative action. Murray et al. [

5] conceptualize this process in six overlapping stages: prompts, inspirations, and diagnoses—the initial recognition of social needs or problems that catalyze innovation; proposals and ideas, where novel solutions are formulated; prototyping and pilots, involving testing and refining in real-world contexts; sustaining, which embeds practices into routine use; scaling and diffusion, where innovations spread to new contexts; and systemic change, marking the reconfiguration of broader social or institutional systems [

5]. These stages closely correspond with components commonly found in social innovation frameworks: novelty aligns with initial idea generation; process overlaps with piloting and embedding; heterogeneity reflects the diverse actors engaged across stages; benefit and impact creation emerges as innovations deliver value during sustaining and scaling; encouraging changes corresponds to systemic transformation; and adaptation and scalability encapsulates the phases of diffusion and institutionalization. Viewing innovation through this integrated lens not only underscores the multiple dimensions at play but also elucidates how ideas evolve from triggers to transformative social systems.

By situating therapy farms within the broader tradition of social innovation, it becomes evident that they not only address individual well-being but also contribute to systemic transformations in rural areas—reshaping the dynamics of community life, creating inclusive employment opportunities, and promoting sustainable development. This dynamic can be conceptualized as a cyclical process (see

Figure 1), where therapy farms emerge from local needs, mobilize community resources, generate new forms of cooperation, and in turn reinforce rural resilience and innovation capacity.

The role of rural communities is therefore central in the implementation of social innovations. In June 2021, the European Commission presented its Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas in the EU until 2040 [

53]. This strategy sought to provide new impetus for rural regions by reshaping perceptions, creating opportunities, and empowering rural communities. Such empowerment is vital, since the future of Europe cannot be built without rural areas. Data from the Rural Observatory show that rural residents place greater trust in local and regional authorities (61%) than in national authorities (31%) or the European Union (47%) [

54]. This highlights the importance of local governance structures as drivers of social and economic transformation.

The review of the main EU documents emphasizes that rural communities must be empowered as key actors in Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) strategic plans, particularly in addressing challenges related to employment, social inclusion, and service provision [

54]. CAP support is expected to strengthen advanced villages, both within and beyond the LEADER initiative, enabling them to harness the potential of digital, social, and technological innovations [

55]. Rural organizations are therefore increasingly engaged in creating change, with social issues becoming more central to their missions.

Scholars note that social innovations aimed at meeting societal needs [

13,

56] are important catalysts for rural development [

49,

57]. They motivate rural actors to participate actively in transformation processes [

58], to reconfigure established forms of cooperation [

49,

59], and to experiment with new methods of operation. Furthermore, social innovation can foster collective action and generate shared power or empowerment among diverse rural organizations [

60]. In this sense, the development of social innovations that involve rural organizations can serve as a driving force for breakthroughs in rural areas, creating prosperity and resilience [

61]. Therapy farms, situated at the intersection of agriculture, health, and community development, exemplify this dynamic by mobilizing local resources and capacities to deliver innovative solutions to both social and economic challenges.

Although social innovation has been widely studied in urban contexts and across sectors such as education, health, and governance, there is still limited research on how rural-based social innovations, particularly therapy farms, function as both opportunities and constraints for broader social transformation. Existing literature frequently emphasizes the contribution of therapy farms to social inclusion, health, and employment, highlighting their capacity to enable social innovation and foster social change at the local level. However, less attention has been given to their ambivalent role: while they generate well-being and resilience within communities, their embeddedness in existing socio-economic arrangements may also shape the limits of broader structural transformation.

The aim of this article is therefore to critically examine therapy farms as social innovations in rural areas, analyzing their potential—both to foster social inclusion and community well-being, and to constrain deeper processes of social transformation. By adopting a case study approach, the study seeks to illuminate how therapy farms simultaneously open new possibilities for rural development while also reproducing certain structural limitations, thereby contributing to ongoing debates on the transformative capacity of social innovation.

The paper is structured into five main sections. The Introduction outlines the conceptual framework of social innovation and situates therapy farms within broader discourses on rural development and social transformation. The Materials and Methods section presents the qualitative case study design, describes the empirical context of the House of Educational Experiences, and explains the analytical framework grounded in the social innovation cycle. The Results section reports the main empirical findings, highlighting how the therapeutic farm generates individual and community-level benefits while operating within structural and institutional constraints. The Discussion critically interprets these findings in light of the transformative potential and limitations of therapy farms as social innovations in rural areas. Finally, the Conclusions summarize the study’s key insights and propose policy recommendations aimed at strengthening the systemic impact, sustainability, and integration of therapy farms within broader social innovation ecosystems.

3. Results

The House of Educational Experiences [

66] was established in 2022 in the ethnographic village in Šalčininkai district, Lithuania. Developed by a team of psychologists, educators, and social workers, the initiative emerged from many years of professional engagement in education, health, and social services. Its founders had repeatedly encountered children and young people who felt excluded, unsafe, or socially disconnected and often expressed this through behavioral and emotional difficulties. These experiences inspired the vision to create a therapeutic space grounded in nature, where young people could experience community, develop self-worth, and engage in meaningful relationships and activities. The result was a year-round therapeutic farm established in a repurposed former school building, where the natural environment, group dynamics, and structured hands-on tasks form the core of a long-term social innovation process.

The goal of the therapeutic farm is to foster personal transformation and social integration among youth at risk, especially those from socially vulnerable backgrounds or institutional care systems. Using principles from environmental and occupational therapy, the program helps participants cultivate self-confidence, develop social and vocational skills, and rebuild fractured relationships. The farm functions not only as a site of healing and skill development but also as a prototype for a new model of youth support in rural Lithuania. Through structured daily routines, interaction with animals and plants, and shared responsibility in a safe group setting, young people gradually strengthen their capacity to re-enter the education system or labor market. The initiative, funded in part by the European Economic Area and Norway Grants (2014–2021), exemplifies a novel, adaptable, and socially impactful model of rural innovation that aligns closely with all six elements of the social innovation cycle: novelty, process, benefit and impact, heterogeneity, encouraging change, and adaptation and scalability.

3.1. Growing the Idea: Reimagining Youth Integration Through Nature-Based Therapy

The House of Educational Experiences represents a novel approach within Lithuania’s social support landscape by integrating therapeutic, educational, and agricultural practices into a unified rural initiative tailored to socially at-risk youth. While therapeutic farming is an emerging model internationally, it remains relatively underdeveloped in Lithuania. This initiative stands out as one of the first structured attempts to adapt and institutionalize the therapeutic farm model in the local context. The founding idea, to create a place where nature, community, and meaningful activity converge to support youth in crisis, differs markedly from conventional social or psychological interventions that are often institutional, short-term, or heavily clinical in nature. The farm operates as an environment where animals, plants, people, and rhythms of the land become therapeutic instruments, offering a restorative space grounded in ecological and social connectedness.

One of the most significant markers of novelty lies in how the therapeutic process is embedded in daily, practical, and repetitive tasks. Instead of isolating therapy into fixed-time consultations, the initiative brings young people into a setting where learning, healing, and personal development emerge through physical work, group responsibility, and natural cycles. These include growing crops, cooking meals, cleaning, and caring for animals—activities that typically fall outside the remit of social services, but here are redefined as tools for rehabilitation and empowerment. Importantly, this model reintroduces a sense of agency and competence for individuals often labelled as ‘difficult’ or ‘marginalised’, by enabling them to experience success and contribution in concrete, observable ways.

Another novel element is the way the initiative reconfigures therapeutic relationships. Instead of positioning professionals as distant authorities, the farm team, comprising psychologists, social workers, and youth educators, acts as co-participants in shared daily routines. This approach transforms traditional power dynamics and facilitates the development of horizontal, trust-based relationships. Youth are not treated as passive recipients of services but as active members of a temporary micro-community. The working group becomes both the medium and the message: collaboration, care, and personal responsibility are experienced directly, rather than abstractly taught. This methodology reflects a fundamental innovation in how social work is conceptualised and embodied, moving away from top-down behavioural correction toward relational, immersive learning.

Finally, the House of Educational Experiences demonstrates innovation by designing a transdisciplinary model that merges multiple sectors: education, mental health, agriculture, and social policy, into one cohesive intervention. By doing so, it addresses the fragmentation often found in traditional youth services. The model itself is adaptive and modular: the farm is not just a therapeutic tool but also a pedagogical setting, a vocational training space, and a soft re-entry point into society. The combination of these roles under one roof, within a rural and community-based setting, introduces a new systemic template for rural social innovation—one that can inspire policy shifts and institutional learning across domains traditionally treated as separate.

3.2. Process: Building Therapeutic Structures Through Everyday Practices

The development of the House of Educational Experiences’ therapeutic farm was grounded in a carefully constructed process that combined professional expertise, community engagement, and methodological adaptation. At its core, the initiative evolved from years of practical engagement with socially vulnerable youth in education, health, and social services. The project officially began in 2022 with funding support from the European Economic Area and Norway Grants. This allowed the team, composed of psychologists, educators, youth workers, and social workers, to convert a former school in the rural village of Seno Strūnaitis into a year-round therapeutic and educational farm. From the outset, the project was not implemented as a fixed or pre-packaged service model but developed through iterative co-creation, adjusting to the real needs of participants and responding to what was feasible within the rural setting.

The therapeutic process is structured around three key pillars: nature, group, and meaningful activity. These are not symbolic concepts but functional components embedded in the farm’s daily rhythm. For instance, each day begins with a ‚sharing circle‘, in which participants reflect on their thoughts and feelings, setting the tone for the work ahead. Participants are then engaged in hands-on tasks, such as gardening, cooking, animal care, and maintenance work under the guidance of professionals who accompany them throughout the day. These activities are designed to foster social skills, emotional regulation, resilience, and self-efficacy, with every step reinforcing the broader goal of reintegration into education or the labour market. The process is thus one of experiential learning, where healing and skill-building are integrated into the routine of work and life rather than delivered through episodic interventions.

Central to the methodology is the use of repetition and predictability as therapeutic tools. For many participants—particularly those with a history of institutionalisation, trauma, or behavioural challenges—the creation of a safe and predictable environment is a precondition for engagement. The consistent structure of the programme (e.g., attending once a week for a full year) is essential to re-establishing broken relational patterns and building trust in adults and peers. Moreover, the use of group-based activities cultivates a micro-community in which participants experience acceptance, interdependence, and accountability. This collective format is essential to the therapeutic process, allowing individuals to rehearse social behaviours in a low-risk setting before re-entering school or employment contexts.

In addition to therapeutic farming, the programme includes career guidance, personal goal-setting, and vocational orientation. Young people are supported in exploring their own strengths, with some continuing into further training or education. For example, two participants with autism spectrum disorder who had never cooked before were able to learn cooking at the farm and later continued their education at a vocational training centre. This transition is not left to chance: the farm facilitates visits to vocational schools, employers, and educational institutions, helping participants envision a future trajectory. In this way, the therapeutic process is embedded within a developmental arc, extending beyond the farm into the broader social system, and reinforcing the notion that therapy, learning, and life planning are interconnected. The result is a practice model that aligns professional intervention with youth-led growth, embedded in the physical and symbolic space of the farm.

3.3. Benefit, Value for Society and Impact Creation

The House of Educational Experiences creates multidimensional benefits that span individual transformation, social cohesion, and systemic inclusion. At the individual level, the therapeutic farm serves as a critical space for restoring emotional safety, self-confidence, and interpersonal trust among vulnerable young people aged 14 to 24, many of whom have histories of trauma, behavioural difficulties, institutionalisation, or exclusion from mainstream education and labour markets. Through the farm’s structured routine, therapeutic environment, and supportive group dynamics, these individuals are not merely treated as clients, but are engaged as active participants in their own healing and development. This approach fosters a sense of agency, accountability, and belonging—conditions that are essential for long-term personal growth and reintegration into society.

The broader social value of the initiative is most clearly visible in its ability to create bridges between otherwise disconnected social systems. The farm works closely with families, schools, foster care institutions, and public authorities to ensure that progress made during the programme is reinforced and sustained. This networked collaboration contributes to wider societal goals such as crime prevention, education retention, and reduction in youth unemployment. The results from 2022–2023 alone illustrate this potential: out of 31 participants who had previously disengaged from education or work, 18 successfully re-entered the education system or the labour market. These outcomes not only reflect the immediate impact of the farm but also generate long-term public value by reducing the costs of social services, criminal justice interventions, and unemployment-related welfare.

Beyond its direct outputs, the initiative contributes to a deeper cultural shift in how society perceives youth at risk. In a context where such individuals are often stigmatised or pathologised, the farm promotes a new narrative that recognises the capacity of every person to grow, contribute, and belong—given the right environment and support. The therapeutic farm becomes a space of social reinvention, where concepts like community, work, and care are redefined through relational and embodied practice. By welcoming and valuing difference, the initiative challenges dominant norms of productivity, education, and citizenship, and in doing so, generates intangible but powerful impacts on the social fabric—especially in rural areas, where exclusion is often intensified by geographic isolation.

Finally, the initiative’s value creation is not limited to youth. The ripple effects extend to local residents, municipal authorities, schools, and policy networks. For example, the participation of local community members in providing services or engaging in dialogue around youth needs fosters shared ownership and local solidarity. Similarly, by cooperating with ministries and social services, the farm contributes to the institutional learning necessary for replicating successful interventions. In this way, the House of Educational Experiences not only generates impact at the level of the individual or community but also contributes to policy innovation and systemic resilience, reinforcing the broader claim that social innovation can be a driver of inclusive rural development.

3.4. Heterogeneity: Diversity of Actors, Needs, and Relationships

Heterogeneity is at the core of the House of Educational Experiences model, both in terms of the target group it serves and the network of actors it mobilizes. The therapeutic farm engages with a wide spectrum of young people, those coming from foster care systems, institutional settings (such as psychiatric day hospitals and socialisation centres), socially at-risk families, and young individuals experiencing psychological distress or behavioural challenges. These youth are not a homogenous group; their backgrounds, needs, and personal trajectories vary widely. This diversity is embraced, not avoided: rather than applying a uniform model of care, the therapeutic programme is highly individualised, allowing each participant to find their own place within the group and to progress at a pace and pathway that suits their abilities and life context.

The heterogeneity of the initiative is also reflected in the composition and values of its professional team. The staff includes psychologists, social workers, youth workers, educators, and even local residents, all of whom contribute from their own fields of knowledge and lived experiences. This multi-professional and interdisciplinary setup enables the initiative to address complex needs from multiple angles: psychological, educational, social, and practical. The team’s collaborative, non-hierarchical style fosters an environment where professional knowledge is integrated with empathy, relational awareness, and responsiveness to context. These interactions generate a collective intelligence that strengthens the adaptive capacity of the farm as a living, evolving system.

In addition, the initiative is embedded within a complex web of institutional and community relationships that span public and private sectors. The farm actively collaborates with local municipalities, general education schools, foster families, health services, and NGOs. It also engages with national ministries and transnational partners, such as the Norwegian Hestegarden Therapeutic Farm, which served as a learning site during the project’s design phase. These partnerships are not merely transactional—they are mutually reinforcing, enabling knowledge exchange, strategic guidance, and resource pooling. By maintaining such a broad and open network, the farm amplifies its own learning and resilience, while also increasing its legitimacy within policy and professional arenas.

The openness to different people, perspectives, and institutions also extends to the design of the activities themselves, which include elements of formal therapy, informal learning, peer-to-peer engagement, community involvement, and vocational exploration. This plurality fosters a climate of experimentation and inclusion, where diversity becomes a strength rather than a complication. The farm does not impose a single ‘normative’ model of behaviour or success; instead, it invites young people and professionals alike to contribute to a shared process of discovery, learning, and community-building. In doing so, the House of Educational Experiences exemplifies how heterogeneity, when embraced and managed thoughtfully, can become a critical driver of meaningful and resilient social innovation.

3.5. Adaptation and Scalability: From Local Innovation to Transferable Practice

From its inception, the House of Educational Experiences was designed not only as a local intervention but as a model with adaptive and replicable potential. Although rooted in the specific rural context of rural areas in Lithuania, the therapeutic farm was built upon flexible principles that allow for transfer and scaling. The team behind the project intentionally drew inspiration from international models, most notably through collaboration with the Hestegarden Therapeutic Farm in Norway, where the staff undertook study visits and experiential learning. These cross-border exchanges helped the team translate abstract insights into context-sensitive practices, aligning global knowledge with local realities. The implementation of the Lithuanian initiative thus reflects a key characteristic of social innovation: combining novelty with adaptability, enabling replication while remaining responsive to contextual conditions.

In practical terms, the therapeutic farming methodology has already shown signs of scalability within Lithuania, particularly through informal diffusion. The team has been invited to share their experience with other professionals working with youth in crisis, such as case managers, social workers, child protection specialists, and career counsellors across different municipalities. These engagements are creating seeds of replication: professionals introduced to the concept are now considering how to integrate elements of therapeutic farming into their own institutional or community-based work. Moreover, some of the farm’s core methods, such as combining vocational training with social therapy or using daily rhythm as a behavioural intervention, are applicable across different settings, from schools to residential centres. This suggests that the initiative offers not just a model service, but a methodological toolkit that can be embedded into broader youth policy and care ecosystems.

However, the project team remains acutely aware of the structural and bureaucratic barriers to scaling. While there is interest from local governments and educational or health authorities, these needs often remain unmet due to systemic constraints: fragmented funding, rigid project cycles, or the absence of long-term institutional frameworks for youth inclusion. To counter this, the farm has prioritised organisational independence, maintaining flexibility to respond to both the local environment and national policy shifts. Yet, its long-term vision is to ensure sustainable public financing, moving beyond dependence on temporary project-based funding toward structural integration into national care and education systems.

Crucially, the adaptability of the model is also internal: the programme itself is continuously evolving. For instance, the team has begun extending services to broader age groups, adapting the method to children and adolescents beyond the original 14–24 age range. They have also expanded the format to include camps, day-long experiences for school classes, and activities for family members. These expansions are not add-ons but structural adaptations, designed to widen the farm’s accessibility and deepen its societal value. Through this evolution, the House of Educational Experiences demonstrates that adaptation and scalability are not only external ambitions but internal capabilities which are integrated into the DNA of the innovation itself.

3.6. Encouraging Changes: Transformative Potential and Structural Shifts

The House of Educational Experiences is not only a place of individual transformation, but it is a vehicle for structural change in rural youth care, education, and community life. Its therapeutic farm model offers an alternative to institutionalised responses that often reinforce marginalisation by separating young people from everyday life, nature, and community. By contrast, this initiative creates a lived example of how inclusive, community-embedded interventions can help youth at risk reintegrate into society. In doing so, it challenges prevailing assumptions about what support should look like for socially vulnerable youth and redefines what it means to create a ‘safe’ environment—not as a space of control, but one of participation, connection, and responsibility.

The programme encourages change not only by intervening in the lives of individual young people but also by disrupting the cycle of exclusion that many of them have experienced across multiple institutions (e.g., foster care, closed centres, psychiatric units). By working directly with education systems, employers, and families, the therapeutic farm bridges gaps that often remain unaddressed in siloed service models. It also models a form of care that is relational rather than procedural, grounded in trust rather than surveillance. This relational logic is powerful: participants do not just acquire skills—they learn new ways of relating to themselves, others, and the world. This is the deep level of change the initiative seeks to foster.

At the systemic level, the farm is increasingly recognised as a catalyst for policy dialogue and professional innovation. Its cooperation with national ministries and municipalities, although currently tied to project-based funding, has the potential to influence how youth care and social services are designed in the future. The team’s participation in cross-sector discussions and regional partnerships is already helping to raise awareness of alternative methodologies such as therapeutic farming. Additionally, their role in building the foundations for a future network of therapeutic farms in Lithuania reflects a broader movement toward institutional change—an effort to shift from fragmented, reactive care systems to proactive, holistic, and participatory models of youth empowerment.

Despite these promising dynamics, the organisation is keenly aware of the tensions between transformation and sustainability. The demand for therapeutic farm services is growing, and the external environment (local authorities, schools, healthcare providers) often expresses a need for more such initiatives. However, bureaucratic obstacles and funding limitations remain significant barriers to structural scale-up. For the team, then, encouraging change means more than implementing new methods—it requires navigating, negotiating, and gradually reshaping the institutional frameworks that surround them. Their ongoing work points to a core paradox of social innovation: it must operate within the very systems it seeks to transform. In this sense, the House of Educational Experiences is both a pioneering practice and a pressure point, a site where new possibilities are made real, but also where the limits of current systems are made visible.

4. Discussion

Therapeutic farming has increasingly attracted attention as a hybrid practice that intersects social care, education, mental health, and sustainable agriculture. In rural contexts especially, it has emerged as a promising response to persistent challenges of youth exclusion, underemployment, and lack of accessible psychosocial services. Previous research on care and social farming highlights the role of agricultural settings as therapeutic landscapes, where engagement with land, animals, and routine practices contributes to psychological well-being and social reintegration [

43,

44,

45]. These farms serve not only as sites of healing but also as microcosms for testing new ways of living and relating, grounded in nature, community, and experiential learning. As such, they offer a lens through which to examine how local, community-based interventions can act as both agents of change and instruments of social continuity. The findings from the interview data highlight both the transformative and stabilizing dimensions of therapeutic farming, providing valuable insights into the ambivalence of social innovation in practice.

As numerous scholars have noted, social innovation is not merely about solving isolated social problems but about reshaping social relations and governance structures [

5,

6]. The House of Educational Experiences illustrates this potential through its creation of an alternative space where vulnerable youth are re-integrated into society via a combination of therapy, meaningful work, and community belonging. This aligns with evidence from the green care literature, which demonstrates that farm-based interventions can enhance psychosocial resilience, emotional regulation, and social functioning, particularly among individuals experiencing vulnerability or trauma [

40,

41,

46]. Participants develop psychosocial resilience, vocational skills, and interpersonal competence, which directly support the goals of inclusion and empowerment often attributed to social innovation [

49]. Indeed, as the interview data confirms, many participants re-enter education or the labor market after the program, indicating real, measurable benefits to individuals and communities. The analysis of the therapeutic farm also supports the theoretical understanding of the complexity of social innovations [

2,

3], as an initiative that originated within the domain of health care but subsequently expanded into a broader social system, thereby reinforcing the notion that therapy, learning, and life planning are intrinsically interconnected. Such interconnections between care, work, and rural space have been identified as a defining characteristic of care farming across Western European contexts [

42].

However, the case study also supports the growing body of literature that critiques the limitations of community-based social innovation in rural areas [

57,

59]. While the farm challenges traditional models of care and therapy, it does so within a framework that does not radically alter the socio-economic structure of rural society. In fact, its reliance on project-based funding, the selective targeting of marginalized youth, and the integration into existing educational and social service systems may function to reproduce existing patterns of exclusion and dependency. Similar tensions have been identified in studies of care farming, where innovative therapeutic practices coexist with welfare and policy arrangements that constrain broader systemic change [

41,

45]. As MacCallum et al. [

13] argue, social innovation can sometimes serve as a ‘compensatory mechanism’ rather than a transformative one, offering localized solutions that leave broader structural inequalities untouched.

The concept of ambivalence in social innovation is particularly important here. While the House of Educational Experiences undoubtedly meets a critical social need and offers new relational and operational models, its broader societal impact remains circumscribed. As Bock [

57] notes, social innovations often operate in a space where they must conform to institutional expectations to survive, thereby compromising their radical potential. This is evident in the therapeutic farm’s gradual shift towards formal partnerships with ministries and its desire for long-term funding through public channels. Research on the institutionalization of care farming similarly suggests that increased policy recognition can enhance stability while simultaneously narrowing the scope for experimentation and critical challenge [

42,

44]. Such institutionalization may enhance sustainability but also risks diminishing the disruptive quality that characterizes more radical forms of innovation [

5] (Murray et al., 2010).

Moreover, the therapeutic farm model fits within what Moulaert and MacCallum [

51] call ‘territorial social innovation’, which is highly contextual and embedded within specific localities. This embeddedness is both a strength and a limitation. On one hand, it ensures that interventions are tailored to real needs and capable of mobilizing local resources. On the other hand, it limits scalability and the capacity to challenge macro-level forces such as regional economic decline or policy-driven marginalization. On the other hand, as highlighted in studies of care farming in rural regions, strong place-based embeddedness may limit transferability and broader policy uptake [

40,

45]. The House of Educational Experiences, for example, has inspired similar practices and has engaged with international partners, but its core activities remain confined to one geographic and demographic niche.

Despite these limitations, the farm serves as a vital experimental space where new forms of care, education, and labor are tested and refined. It also demonstrates that the success of social innovation should not be judged solely on scalability or systemic disruption but also on the ability to create inclusive and humane spaces for social learning and recovery. This resonates with the green care literature, which emphasizes the intrinsic value of therapeutic processes and relational outcomes alongside measurable socio-economic effects [

43,

46]. This aligns with the notion that social innovation is a process as much as an outcome [

5], and that its value lies in its capacity to nurture alternative social logics, even if these do not immediately translate into structural transformation.

Future research should build on these insights by conducting comparative studies of rural therapy farms across different national and institutional contexts. Longitudinal research could also help assess whether and how participants sustain the gains made during therapeutic programs over time. Finally, more attention should be given to how such initiatives can balance the tension between institutional integration and transformative ambition, ensuring that their social innovation potential does not become a vehicle for the soft management of inequality.

This study also comes with certain limitations. As a single case study grounded in qualitative interviews, the findings are context-specific and may not be generalizable to all rural therapy farms or social innovations more broadly. While the depth of insight into the House of Educational Experiences is valuable, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential bias, and the absence of longitudinal follow-up limits understanding of long-term impacts. Furthermore, the dual role of researchers as interpreters and analysts means that the findings are inevitably shaped by subjective framing, even when grounded in empirical evidence. Future studies could benefit from triangulating qualitative insights with quantitative data and expanding the research across multiple sites and timeframes.