Relationship Between Emotional Self-Regulation and the Perception of School Violence: Pilot Study in La Araucanía, Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis Plan

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Results for a Theoretical Model

Methodological Analysis of Results to Support a Theoretical Model

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santre, S. Mental Health Promotion in Adolescents. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, D.; Fang, X.; Elliott, S.; Casey, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Florian, L.; McCluskey, G. The Relationships between Violence in Childhood and Educational Outcomes: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 75, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmeyer, B.; Threadgold, S. Bullying Affects: The Affective Violence and Moral Orders of School Bullying. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2023, 64, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, U.; Kwon, M.; You, S. Transition From School Violence Victimization to Reporting Victimized Experiences: A Latent Transition Analysis. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 37, 9717–9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F. Del Aprendizaje En Escenarios Presenciales al Aprendizaje Virtual En Tiempos de Pandemia. Estud. Pedagógicos 2020, 46, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Ramirez, L. Acoso Escolar Cibernético En El Contexto de La Pandemia Por COVID-19. Rev. Cuba. Med. 2020, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Hofflinger, Á.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, R.; Vegas, E. Chile: From Closure to Recovery: Tracing the Educational Impact of COVID-19. In Improving National Education Systems After COVID-19; Crato, N., Patrinos, H.A., Eds.; Evaluating Education: Normative Systems and Institutional Practices; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 17–36. ISBN 978-3-031-69283-3. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Troncoso, F.; Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Riquelme-Mella, E.; Muñoz-Troncoso, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Bizama-Colihuinca, K.; Legaz-Vladímirskaya, E. Validation of an Abbreviated Scale of the CENVI Questionnaire to Evaluate the Perception of School Violence and Coexistence Management of Chilean Students: Differences between Pandemic and Post-Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordán, M.B.; Lira, E. Violencia Escolar y Ciberbullying En El Contexto de La COVID-19. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Campus of Huesca, Zaragoza, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL. La Educación En Tiempos de La Pandemia de COVID-19; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MINEDUC Estadísticas de Denuncias Superintendencia de Educación. Available online: https://www.supereduc.cl/denuncias-ingresadas/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Maturana, H. Transformación en la Convivencia; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; ISBN 978-956-9987-55-7. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. El Político y el Científico; el libro de bolsillo; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1998; ISBN 978-84-206-6939-7. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J. La Violencia: Cultural, Estructural y Directa. In Cuadernos de Estrategia 183. Política y Violencia: Comprensión Teórica y Desarrollo en la Acción Colectiva; Ministerio de Defensa: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. Topología de la Violencia; Pensamiento Herder; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-84-254-3417-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mella, M.; Binfa, L.; Carrasco, A.; Cornejo, C.; Cavada, G.; Pantoja, L. Violencia Contra La Mujer Durante La Gestación y Postparto Infligida Por Su Pareja En Centros de Atención Primaria de La Zona Norte de Santiago, Chile. Rev. Méd. Chile 2021, 149, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud; University of Cape Town; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). La Prevención de la Violencia: Evaluación de los Resultados de Programas de Educación Para Padres; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978-92-4-350595-4.

- Cuadrado, I. Divergence in Aggressors’ and Victims’ Perceptions of Bullying: A Decisive Factor for Differential Psychosocial Intervention. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, R.; Patchin, J.; Young, J.; Hinduja, S. Bullying Victimization, Negative Emotions, and Digital Self-Harm: Testing a Theoretical Model of Indirect Effects. Deviant Behav. 2022, 43, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utley, J.W.; Sinclair, H.C.; Nelson, S.; Ellithorpe, C.; Stubbs-Richardson, M. Behavioral and Psychological Consequences of Social Identity-Based Aggressive Victimization in High School Youth. Self Identity 2022, 21, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, V.; Deaño, M.; Tellado, F. Incidencia de Los Distintos Tipos de Violencia Escolar En Educación Primaria y Secundaria. AULA_ABIERTA 2020, 49, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, N. The Effect of Violence in Childhood on School Success Factors in US Children. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 120, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guajardo, G.; Toledo, M.; Miranda, C.; Sáez, C. El Uso de Las Definiciones de Violencia Escolar Como Un Problema Teórico. Cinta Moebio 2019, 1, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Ascorra, P.; Bilbao, M.; Carrasco, C. De La Violencia a La Convivencia Escolar: Una Década de Investigación. In Una Década de Investigación en Convivencia Escolar; Ascorra, P., López, V., Eds.; Ediciones Universidad de Valparaíso: Valparaíso, Chile, 2019; pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cedeño, W. La Violencia Escolar a Través de Un Recorrido Teórico Por Los Diversos Programas Para Su Prevención a Nivel Mundial y Latinoamericano. Rev. Univ. Soc 2020, 12, 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez, E.; Jiménez, T.I.; Segura, L. Emotional Intelligence and Empathy in Aggressors and Victims of School Violence. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León del Barco, B.; Lázaro, S.; Polo del Río, M.-I.; López-Ramos, V.-M. Emotional Intelligence as a Protective Factor against Victimization in School Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.-K. Emotional Intelligence and School Bullying Victimization in Children and Youth Students: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, L.; Meloni, S.; Lanfredi, M.; Rossi, R. School-based Interventions to Improve Emotional Regulation Skills in Adolescent Students: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuso, S.; Severo, M.; Ventriglio, A.; Bellomo, A.; Limone, P.; Petito, A. Psychoeducation Reduces Alexithymia and Modulates Anger Expression in a School Setting. Children 2022, 9, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usán, P.; Quílez, A. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance in the Academic Context: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in Secondary Education Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.A.D.; Esteca, A.M.N.; Wechsler, S.M.; Menesini, E. Bullying and Cyberbullying in School: Rapid Review on the Roles of Gratitude, Forgiveness, and Self-Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Jorquera, A.B.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Martínez-Ramón, J.P.; Fernández-Sogorb, A. Emotional Intelligence, Bullying, and Cyberbullying in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Resultados CENSO. 2017. Available online: http://resultados.censo2017.cl/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Quilaqueo, D.; Quintriqueo, S.; Torres, H.; Muñoz, G. Saberes Educativos Mapuches: Aportes Epistémicos Para Un Enfoque de Educación Intercultural. Chungará Rev. Antropol. Chil. 2014, 46, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, O.; Montero, I. Metodos de Investigacion Psicologia y Educacion: Las Tradiciones Cuantitativa y Cualitativa, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-486-2050-9. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Tapia, J.; Panadero-Calderón, E.; Díaz-Ruiz, M.A. Development and Validity of the Emotion and Motivation Self-Regulation Questionnaire (EMSR-Q). Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B.; Shamoo, A.E. The Singapore Statement on Research Integrity. Account. Res. 2011, 18, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MINSAL. Ley 20.120. Sobre La Investigación Científica En El Ser Humano, Su Genoma, y Prohibe La Clonación Humana. Rev. Chil. Obstet. Ginecol. 2006, 72, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 1999; ISBN 64-8322-035-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.; Abalo, J.; Rial, A.; Braña, T. Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio de Segundo Nivel. In Modelización con Estructuras de Covarianza en Ciencias Sociales: Temas Avanzados, Esenciales y Aportes Especiales; Lévy, J.P., Varela, J., Eds.; Netbiblo: Madrid, Spain, 2006; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio 2024.09.1; RStudio: Boston, MA, USA, 2024.

- González, A.; Molero, M. Healthy Lifestyle in Adolescence: Associations with Stress, Self-Esteem and the Roles of School Violence. Healthcare 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil, R.; Mestre, J. Violencia Escolar: Su Rel-Ación Con Las Actitudes Sociales Del Alumnado y El Clima Social Del Aula. Rev. Electrónica Iberoam. De Psicol. Soc. 2004, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, P.J.; Costa, A. Teaching Emotional Self-Regulation to Children and Adolescents. In Fostering the Emotional Well-Being of Our Youth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 264–281. ISBN 978-0-19-091887-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Cobo, M.J.; Megías-Robles, A.; Gómez-Leal, R.; Cabello, R.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Emotion Regulation Strategies and Aggression in Youngsters: The Mediating Role of Negative Affect. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäker, N.; Wilke, J.; Eilts, J.; Von Düring, U. Understanding the Complexities of Adolescent Bullying: The Interplay between Peer Relationships, Emotion Regulation, and Victimization. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2023, 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Cerolini, S.; Zegretti, A.; Zagaria, A.; Lombardo, C. Bullying Victimization and Adolescent Depression, Anxiety and Stress: The Mediation of Cognitive Emotion Regulation. Children 2023, 10, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Nava, E. The Long-Term Effects of Bullying, Victimization, and Bystander Behavior on Emotion Regulation and Its Physiological Correlates. J Interpers Violence 2022, 37, NP2056–NP2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addai, P.; Okyere, I.; Ako, M.; Wiafe-Kwagyan, M.; Owusu, J. Self-Regulation of Emotions in Relation to Students’ Attitudes Towards School Life. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2023, 12, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Sehgal, K.; Zieher, A.K.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; et al. The State of Evidence for Social and Emotional Learning: A Contemporary meta-analysis of Universal school-based SEL Interventions. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S.R.; Valente, J.Y.; Caetano, S.C.; Martins, S.S.; Sanchez, Z.M. Worldwide School-Based Psychosocial Interventions and Their Effect on Aggression among Elementary School Children: A Systematic Review 2010–2019. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 55, e101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadeh, H.-M.; Breaux, R.; Nikolas, M.A. A Meta-Analytic Review of Emotion Regulation Focused Psychosocial Interventions for Adolescents. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickerell, L.E.; Pennington, K.; Cartledge, C.; Miller, K.A.; Curtis, F. The Effectiveness of School-Based Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioural Programmes to Improve Emotional Regulation in 7–12-Year-Olds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K.L.; Sanders, M.T. Teaching Explicit Social-Emotional Skills With Contextual Supports for Students With Intensive Intervention Needs. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2021, 29, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trianes, M.; García, A. Educación Socioafectiva y Prevención de Conflictos Interpersonales En Los Centros Escolares. Educ. Socioafectiva Prevención Confl. Interpersonales Los Cent. Esc. 2002, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Aedo, A.; Maddaleno, M.; Ramírez, L. Una Aproximación Sociológica a La Salud Mental de La Adolescencia En Chile. RMS 2025, 87, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINEDUC. Política Nacional de Convivencia Educativa 2024–2030. Marco de Actuación y Visión Institucional; Ministerio de Educación: Santiago, Chile, 2024.

- OECD. Promoting Good Mental Health in Children and Young Adults: Best Practices in Public Health; OECD: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (Ed.) On My Mind: Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health; The state of the world’s children; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-92-806-5285-7. [Google Scholar]

- Berastegui-Martínez, J.; Ángeles De La Caba-Collado, M.; Pérez-Escoda, N. The Impact of the Sentituz Programmes on Emotional Competence and Social Climate in the Classroom. IJEE 2023, 15, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; McGarrah, M.W.; Kahn, J. Social and Emotional Learning: A Principled Science of Human Development in Context. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazzard, J.; Bostwick, R. A Whole School Approach to Mental Health and Well-Being, 2nd ed.; Positive Mental Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-041-05648-5. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Gutiérrez, M.; Caqueo-Urízar, A. The Influence of Social Determinants and 5Cs of Positive Youth Development on the Mental Health of Chilean Adolescents. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

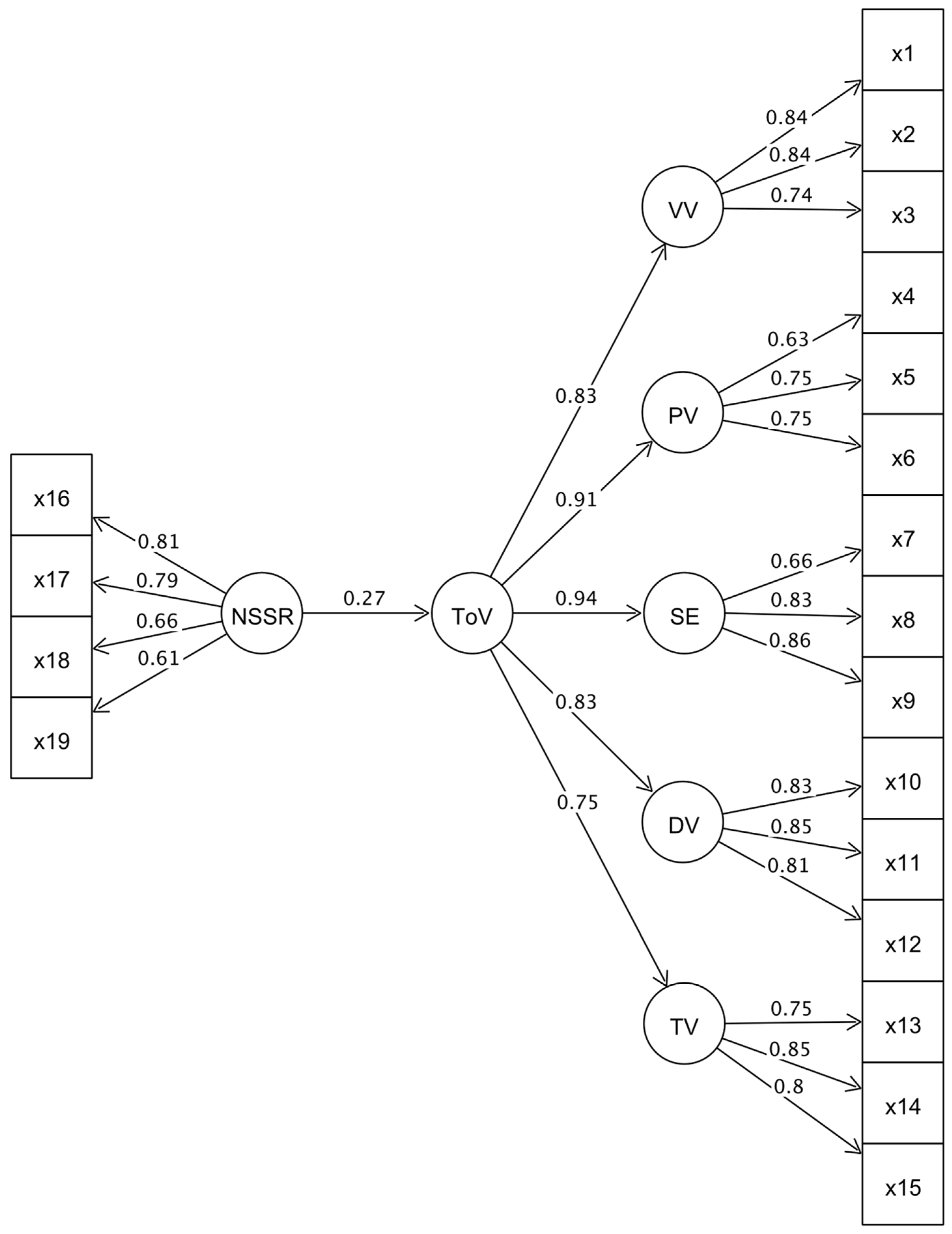

| Second Order | First Order |

|---|---|

| Types of violence (ToV) | Verbal violence (VV) |

| Physical violence (PV) | |

| Social exclusion (SE) | |

| Digital violence (DV) | |

| Teacher violence (TV) | |

| Coexistence management (CM) | Reflection (RE) |

| Education (ED) | |

| Assurance (AS) | |

| Participation (PA) |

| Second Order | First Order |

|---|---|

| Learning self-regulation style (LSR) Avoidance self-regulation style (ASR) | Positive motivation self-regulation (PMSR) |

| Process oriented self-regulation (POSR) | |

| Negative stress self-regulation (NSSR) * | |

| Avoidance oriented self-regulation (AOSR) | |

| Performance oriented self-regulation (POSR) |

| Factor Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Min | Max | AVE | CR |

| Verbal violence (VV) | 0.739 | 0.837 | 0.599 | 0.817 |

| Physical violence (PF) | 0.628 | 0.753 | 0.506 | 0.753 |

| Social exclusion (SE) | 0.664 | 0.855 | 0.622 | 0.830 |

| Digital violence (DV) | 0.812 | 0.852 | 0.691 | 0.870 |

| Teacher violence (TV) | 0.753 | 0.848 | 0.642 | 0.843 |

| Negative stress self-regulation (NSSR) | 0.611 | 0.813 | 0.524 | 0.813 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Troncoso, F.; Riquelme-Mella, E. Relationship Between Emotional Self-Regulation and the Perception of School Violence: Pilot Study in La Araucanía, Chile. Societies 2025, 15, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080221

Muñoz-Troncoso F, Riquelme-Mella E. Relationship Between Emotional Self-Regulation and the Perception of School Violence: Pilot Study in La Araucanía, Chile. Societies. 2025; 15(8):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080221

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Troncoso, Flavio, and Enrique Riquelme-Mella. 2025. "Relationship Between Emotional Self-Regulation and the Perception of School Violence: Pilot Study in La Araucanía, Chile" Societies 15, no. 8: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080221

APA StyleMuñoz-Troncoso, F., & Riquelme-Mella, E. (2025). Relationship Between Emotional Self-Regulation and the Perception of School Violence: Pilot Study in La Araucanía, Chile. Societies, 15(8), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080221