Abstract

Emergency displacement has become an increasingly salient global phenomenon, precipitated by the intensification of climate crises and persistent geopolitical conflicts. These events forcibly displace millions each year and generate complex social, political, and institutional challenges. While the literature on displacement is expanding, much of it centers on individual and household experiences, often overlooking the collective dimensions of displacement. This article addresses this gap by critically examining the concept of the displaced community, a term used to describe collectivities formed in host societies comprising individuals who have been forcibly uprooted. The article undertakes a conceptual investigation of displaced communities, seeking to define their constitutive features while accounting for their internal heterogeneity and contextual variability. To sharpen analytical clarity, the study contrasts displaced communities with healthy communities, thereby situating two polar ends of a continuum. Based on these two types of community, the question arises, “can displaced communities be healthy communities?” The article advances a conceptual model of a healthy displaced community, positing that such a construct extends conventional understandings of resilience by foregrounding the processual dynamics of recovery and adaptation. Specifically, it is argued that community health in contexts of forced displacement must be understood as the outcome of iterative processes intentionally involving community-based intervention, empowerment, and long-term sustainability. Drawing on published case studies and empirical accounts of work with displaced populations, the article demonstrates how these three pillars—community intervention, empowerment, and sustainability—are implemented in practice. It concludes with policy and practice recommendations designed to prevent further deterioration and promote the development of health and well-being within displaced communities.

1. Introduction

In 2023, global displacement reached unprecedented levels, driven by climate change, violent conflicts, and political and economic instability. These factors have exacerbated threats to human security, leading to the highest recorded rates of forced displacement in the modern era. Over 117 million individuals worldwide experienced forced displacement [1,2]. Of these, nearly 76 million people across 148 countries were internally displaced (Global Report on Internal Displacement [3]. Internal displacement refers to migration within a state’s borders, often undertaken in response to the adverse impacts of disasters (International Organization for Migration (IOM) [4].

Displacement is distinct from other forms of migration. It is defined as the “movement of persons who have been forced or obligated to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence… in order to avoid the effects of… disasters” [4]. A disaster, in this context, is understood as a “serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events” [4]. Displacement is characterized by a sense of urgency and force majeure, necessitating involuntary evacuation [5]. Unlike urban forced removals and evictions [6], disaster-induced displacement results in large-scale population movements, often involving the evacuation of entire communities, neighborhoods, or geographical regions. Furthermore, displacement extends beyond the individual or household level; it is inherently a collective phenomenon. As a mass societal experience, displacement affects entire populations within a given territory, reshaping social, economic, and political structures on both local and national scales.

Much has been written about displacement and its effects on individuals and families (e.g., [7,8,9,10]), communities (e.g., [11,12,13]), and society at large (e.g., [14,15,16,17]). The vast literature on the field makes it clear that forced displacement is not a singular monolithic experience but rather a diverse phenomenon, varying in its causes, nature, effects, the populations affected, and its outcomes. First, people are displaced for various reasons that can stem from natural disasters (from earthquakes to persistent droughts) or people-made disasters (from wars to fear of gangs). Second, people may have a different temporal nature of displacement, whereas some may soon go back to their original residency, others may never be able to go back [18]. Third, displaced people can be forced to move to a host country, but they can also be internally displaced in their country of origin [19,20]. Finally, in many cases, people from the same home community, intentionally or not, find themselves together in a safer place, or they may join displaced people from other evacuated communities, bound by shared experiences. In these safer places, displaced people often come to form a new displaced community.

Most of the literature on displacement focuses on individuals and families rather than on communities. To the best of our knowledge, the concept of “displaced communities” remains unexplained, undeveloped, and undefined. While many studies refer to displaced communities (e.g., [5,21,22]), none of them address its meaning or essence, leaving a notable gap in the literature and underscoring a critical need for research and practice. Our review reveals that a formal definition of the term is absent not only in the academic literature but also in key policy platforms (e.g., [1,2,4]). One particularly significant document, the IOM Glossary on Migration [4], compiles and defines a comprehensive list of migration-related concepts spanning nearly 250 pages. The glossary includes hundreds of conceptual, legal, theoretical, and practical terms but not the term displaced community. The only terms that may partially be related to the concept of a displaced community are “home community” and “host community”, neither of which adequately capture the meaning of a displaced community.

Interestingly, the concept of displaced communities is frequently used by scientific fiction authors [23]. Many science fiction authors propose a fabricated reality due to cosmic catastrophes or destruction. These authors conceive of a group of people and at times even machines who intentionally, or by chance, survived and created a substitute community. Science fiction literature often explores themes of displacement, depicting communities uprooted from their homelands and striving to adapt to new environments. These narratives often serve as allegories for real-world issues such as migration, colonization, and social upheaval.

In this article, we explore the concept of a displaced community as a distinct and central phenomenon, drawing on related studies in the field. The analysis acknowledges the dynamic and multidimensional nature of displacement and its broader conceptual implications, thereby demonstrating the complexity and differences that exist among displaced communities. Moreover, we seek to examine whether displaced communities can be healthy. For this purpose, we analyze the body of knowledge on healthy communities [24,25,26,27]. Based on the elucidation of what healthy communities are, we pose a question regarding the interaction between displaced and healthy communities. While displaced communities are typically associated with crisis and instability, healthy communities represent a conceptual framework oriented towards long-term well-being and equity. One is often a collective of people in crisis while the other offers an almost utopian version of community. However, rather than treating them as opposites, we explore how these two constructs can intersect, and how principles of healthy communities may be applied in the context of displacement. In this context, we challenge the widely researched concept of resilience, arguing that while it is important and even essential, it offers an insufficient response to preexisting structural societal challenges, which are often exacerbated by disasters. We explain why the healthy community approach offers a more equitable and long-term response, relevant both in times of routine and in crisis. Based on a systemic literature analysis, we propose a model of a healthy displaced community and examine its feasibility as expressed in a sample of studies on displaced communities worldwide. Our conceptual research concludes with recommendations for policy and practice that may enhance health and well-being among displaced communities. As a growing body of studies highlights the significance of community-based interventions for displaced populations (e.g., [28,29,30,31,32], we assert the need to articulate what constitutes a displaced community and clarify its meaning. We conclude with a discussion and implications for both theory and practice.

2. Displaced Communities

In this section, we explore the concept of displaced communities as they are depicted in published studies. Just as communities are fundamentally diverse and continuously evolving [33], so too are displaced communities, shaped by realities of forced movement and resettlement. Their way of living and being is influenced by multiple factors, making the concept of a displaced community very broad and elusive. Recognizing the trajectory of displacement and its increasing scale, frequency, and complexity [15], we focus on research that examines the collective impact of mass trauma and how it manifests and is approached at the communal level (e.g., [29,30,34,35,36,37]. We begin by unpacking the concept and its representation in the literature, followed by characterizing its essence and proposing a definition for a displaced community.

2.1. Displaced Community: An Uprooted Concept?

At first glance, the concept of a displaced community appears straightforward. For forcibly displaced individuals, congregating within one location often presents a more viable option than facing the crisis in isolation. The alternative—navigating displacement alone or loosely connecting with others who have endured similar losses—can be significantly more challenging. Individuals or families who go at it alone frequently lack opportunities for consultation or emotional support. They must independently navigate unfamiliar environments and locate essential resources. In contrast, many displaced people choose to live in proximity to others from their original community, thereby forming an alternative social structure in exile known as a displaced community [38].

Forced displacement is often associated with a continuous state of transit and movement, as individuals are compelled to leave their homes and communities in search of safety and stability. In contrast, displaced communities tend to exhibit less mobility, functioning as temporary refuges that provide a degree of stability amid displacement. While these communities may not represent the desired destinations of the displaced, they serve as provisional spaces where former neighbors can reconvene and maintain social bonds. In certain cases—such as Palestinian refugee camps—displaced individuals may remain in these communities for generations, often preserving symbolic items like the keys to their original homes, which reflect both a longing to return and a sense of enduring instability [39]. A displaced community ultimately ceases to exist either when its members return to their place of origin or when they become fully integrated into the host society.

The manifestation of displaced communities varies widely. These communities may be in pre-evacuation or post-evacuation sites, depending on temporal and spatial circumstances. As a result, ambiguity surrounds their conceptualization—whether they represent a relocated home community, an integrated segment of a host society, or a temporary shelter-based formation. The concept of a displaced community is not only underdefined but is often referenced implicitly (e.g., [16,21,22]), revealing its complex and multifaceted nature. It may refer to the original home community from which individuals were evacuated or to the new host community where they have been resettled. While the host community is typically defined as “the community in whose neighborhood the displaced people are relocated” [40], the notion of the home community remains relatively unexplored in academic discourse.

Multiple studies advocate for the preservation of communal structures during displacement as a means to mitigate the compounded effects of community loss. Such efforts can simultaneously minimize psychological harm and enhance collective resilience [41,42,43]. Nevertheless, displaced communities do not exhibit uniform characteristics, presenting conceptual challenges in defining what exactly constitutes a “displaced community.”.

In some cases, entire communities are displaced collectively; in others, only a subset of community members is uprooted while others remain [44]. When whole communities are relocated to temporary shelters, many aspects of their previous social fabrics such as neighborly ties, support networks, and leadership structures—may persist, fostering a sense of continuity and collective efficacy [5,45,46]. Conversely, when displacement is fragmented, and individuals are scattered across multiple locations, communal bonds and shared identities are more likely to dissolve.

The timing and process of displacement also vary. Some communities are abruptly uprooted, with members fleeing simultaneously due to acute threats such as earthquakes or military conflict. In other instances, displacement unfolds gradually—often in response to slow-onset crises like water scarcity—leading to a more protracted evolution of displaced communities.

Temporality further complicates our understanding of displaced communities. Much of the literature emphasizes newly formed communities in shelters [47]. These shelters may function merely as physical protection or serve as spaces where new communal identities and support systems are formed, thereby contributing to psychosocial recovery [48]. Although often considered transitory, many displaced communities persist for extended periods—commonly up to three years [49]—and in some cases, displacement becomes permanent due to the impossibility of return, necessitating integration into a new locale [50,51,52].

The causes of displacement—ranging from war and natural disasters to sectarian violence, terrorism, organized crime, or political upheaval—generate different types of forced displacement, each carrying distinct consequences. Some of these causes elicit stronger trauma responses, shaping the resilience or fragility of the displaced community. Moreover, public and host community perceptions of these causes can vary, influencing the social reception and integration of displaced individuals.

The agents responsible for displacement can also differ, influencing how communities form post-displacement. Displacement may be initiated by individuals, families, or state mechanisms, and the resulting living arrangements often depend on the displaced persons’ resources or on state and organizational interventions. In some instances, governments actively facilitate the formation of displaced communities for strategic or logistical purposes.

Internal relationships within displaced communities—shaped by prior communal life, social organization, and formal or informal leadership—play a crucial role in determining their post-displacement cohesion and recovery. For example, original communities with high levels of social capital are more likely to secure resources, services, financial support, and better housing conditions than displaced communities characterized by low social capital. Pre-disaster conditions can mitigate the impacts of post-disaster displacement [53], explaining variations in communities’ ability to cope with emergencies [29].

Host community responses also vary. They may range from support to stigmatization and often to apathy. Host communities, especially for those not in their home country like millions of Syrian refugees, determined how free, supported, and welcome are the displaced communities. The host community also impacts the ability of members of displaced communities to integrate into the host communities.

The conditions in the place of origin, combined with the feasibility of return or the need for permanent resettlement, contribute to the evolving nature of displaced communities. For some, displacement initiates a prolonged and uncertain journey through multiple locations, each move affecting emotional well-being, identity, and resilience.

These interrelated factors collectively shape the diverse realities of displaced communities. Despite this complexity, a unifying feature is the spatial and social proximity of individuals who were forced to flee their homes and seek shelter—either within the same country or internationally—in response to shared threats. However, due to their diversity and fluidity, no single definition can comprehensively capture the essence of a displaced community. Instead, as Hunter [54] proposes, the concept may be best understood through empirical generalization—an approach that acknowledges these multifaceted dynamics and enables analysis through ecological, social, and psychological lenses.

The following section introduces a three-dimensional framework to further explore the characteristics of displaced communities through this typology.

2.2. Towards Definition of a Displaced Community

Research has demonstrated that it is possible to establish communal life and foster a sense of continuity and livelihood even within provisional settings and under uncertain conditions [42,47,55]. The character of such communal existence may either reflect the structure of the pre-displacement community or evolve into a distinctly different formation. In seeking to define what constitutes a displaced community, this study adopts an integrative conceptualization that accounts for ecological, social, and psychological dimensions. Given the multiplicity of definitions of “community” and its inherently dynamic and open-ended nature, this approach draws on the theoretical framework proposed by Hunter [54,56], which builds on Hillery’s foundational work [57].

Hunter’s framework serves as a flexible and organizing model in which a community is understood as a structure, a unit of social organization, or a quality. It encompasses three interrelated dimensions: the ecological, which refers to the physical and temporal context in which the community exists; the social, which encompasses the networks, interactions, and relational ties among its members; and the psychological, which includes symbolic elements such as shared identity, culture, norms, and values. According to this framework, a displaced community may be recognized as such if it develops these three dimensions during the temporary period of displacement—when evacuees reside away from their original home community but remain in relative proximity to one another.

Prior to displacement, a home community often aligns closely with Hunter’s typology, wherein members demonstrate a strong sense of identification with a specific geographic location and engage in established patterns of social and cultural life. However, this alignment becomes more ambiguous following displacement. Can a community still be said to exist when its members are dispersed across multiple shelters? Can it still be a community when their stay is temporary? The answer depends on the particular circumstances of the displacement and the degree to which ecological, social, and psychological dimensions are preserved or reconstituted.

To be recognized as a community displaced individuals must share a common geographic space. They must be clearly congregated in identifiable locales—both to themselves and to members of the host society. Beyond mere physical proximity, a form of shared social life must be sustained, although its structure and intensity may differ from that of the pre-displacement community. Ueda and Shaw [46] underscore the importance of cultivating new communal bonds within shelter environments, acknowledging the difficulties displaced individuals face in maintaining pre-existing social networks. Moreover, shared psychological experiences of trauma often become the foundation for new social relationships among those cohabiting in temporary facilities.

Celestina [58] questioned the legitimacy of communities formed through artificially imposed grouping. In her analysis of psychological commonality among evacuees, she refers to such assemblages as “a so-called displaced community” or “a community thrown together”. She contended that displacement may engender internal hierarchies based on perceived levels of suffering or moral worth, shaped by the differing post-disaster realities experienced by survivors. Consequently, while displacement can generate shared experiences, it does not inherently produce a unified or cohesive community.

A recurring theme in the literature is the interconnectedness between a community’s psychosocial characteristics before and after displacement. Communities marked by strong social cohesion, shared identity, and robust social capital tend to demonstrate greater resilience and organizational capacity during displacement [11,59]. Particularly effective are those with both bonding and bridging forms of social capital, which facilitate internal solidarity and external resource mobilization [30]. Conversely, communities with preexisting vulnerabilities—social, cultural, or economic—are more susceptible to the adverse effects of displacement [60]. Weak external networks can exacerbate the impacts of disaster, resulting in disproportionately severe outcomes.

Indeed, social vulnerability often magnifies the scale of human suffering during displacement. However, strong local cohesion and mechanisms for collective action are known to enhance community resilience [14]. Social cohesion is positively associated with a psychological sense of community, while its absence indicates fragmentation [61]. Disasters frequently rupture established social networks, particularly when displaced individuals are randomly assigned to temporary housing [62]. As such, the loss of community is not solely a spatial loss, but also a social and psychological one—the loss of people, relationships, and shared meanings [32,58].

Regardless of whether a home-based community is preserved or fragmented, all displaced individuals experience a disruption to their place-based identity [5]. This disruption compels survivors to rearticulate their individual and collective identities. Certain elements of the home community—such as a place attachment, environmental familiarity, and the continuity of routines and livelihoods—are irreplaceable, even when an entire community is relocated intact. These elements are central to fostering a sense of belonging and community, which in turn are crucial determinants of well-being [63,64,65,66]. The loss of place, then, is inherently tied to the loss of social and psychological dimensions, deepening the trauma of displacement.

To conclude this examination of what constitutes a displaced community, we propose the following definition, intended to capture the broad, multidimensional nature of the phenomenon:

A displaced community is broadly defined as a group of individuals forcibly removed from their homes due to a disaster or crisis and relocated to a new setting. Within this new context, a significant number of these individuals reside in proximity to one another, form new or reconfigured social structures, and undergo psychological processes shaped by shared experiences of trauma and forced migration. While the specific manifestations of ecological context, social organization, and psychological adaptation vary across displaced communities, these dimensions collectively provide a framework for understanding their commonalities and differences.

With this definition in place, the following section introduces the concept of a healthy community and examines its applicability in the context of displacement, asking whether displaced communities can be considered healthy.

3. The Healthy Community Approach

Examining the potential for displaced communities to be considered healthy necessitates a clear and comprehensive understanding of what constitutes a healthy community. This section introduces the healthy community approach, tracing its origins and outlining its relevance as a valuable framework for understanding and addressing the complexities of displaced communities. Furthermore, it differentiates between the concepts of resilience and the healthy community approach, demonstrating how the latter extends beyond immediate adaptive capacity. The healthy community approach represents a deeper, more sustained expression of resilience, encompassing long-term well-being, social cohesion, and collective agency.

3.1. What Is a Healthy Community?

Emerging in the mid-1980s and inspired by Saul Alinsky’s vision of community organizing and grassroots empowerment [67], the healthy community approach developed in response to the limitations of an overly individualistic medical model in the United States—one that often failed to address the broader environmental and structural determinants of health [27,68]. The approach was first formally articulated in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion by the World Health Organization [69], which advocated an ecological perspective to improve quality of life. Over time, this framework evolved beyond health-specific concerns to become a movement for healthy communities, providing an alternative paradigm to confront broader societal challenges such as poverty, illiteracy, and violence.

Rather than attributing individual struggles to personal failure—commonly referred to as “blaming the victim” [70]—the healthy community approach emphasized the role of structural conditions and collective responsibility. It redirected attention toward dismantling systemic barriers and promoting community-wide solutions [27]. Central to this movement was the belief in the power of ecological systems to overcome challenges in welfare and human services, paired with an emphasis on civic participation as a remedy for fragmented, professionalized service systems that often operate in isolation from the communities they intend to serve [27,68].

A foundational principle of this approach is the empowerment of disenfranchised populations most affected by systemic inequities. It advocates for building community capacity and fostering resident participation in locally relevant solutions. Norris and Pittman [26] characterized the healthy community framework as a philosophy for cultivating communities capable of identifying and addressing their own challenges through inclusive, participatory processes. By mobilizing residents through collective action, the approach seeks to improve the quality of life for all members [24,25,27].

Healthy communities are distinguished by the presence of supportive environmental and social conditions that promote well-being and sustainable change [26,71]. They are built on trust, cooperation, and shared leadership, and operate under a collective vision for the future. These communities are inherently inclusive, embracing diversity and empowering all members to contribute. They also adopt a holistic view of health, encompassing physical, psychological, socioeconomic, and cultural dimensions [72,73].

In this context, Lackey et al. [24] described the healthy community as the goal of community development, outlining four core attributes: (1) attitudes and values, (2) capacities, (3) organization, and (4) leadership. These attributes collectively foster a viable social environment wherein individuals can actively pursue well-being and quality of life. Building on this foundation, Wolff [27] later theorized six guiding principles for healthy communities: (1) fostering genuine collaboration and exchange, (2) embracing diversity, (3) promoting active citizenship and empowerment, (4) leveraging community strengths, (5) acting on a shared vision, and (6) incorporating spiritual inspiration understood as a moral and ethical, rather than a specific faith tradition, dimension.

The healthy community concept has thus evolved significantly—from its early roots in Alinsky’s [74] model of civic engagement and social change, through its articulation as a health-centered ecological model in the WHO’s Ottawa Charter [69], to its current form as an integrated, multidimensional framework for social development and community well-being (e.g., [25,26,27]).

3.2. Healthy Communities in the Context of Displacement

The social dimensions and implications of community health represent domains where individuals and groups possess the greatest agency and capacity to effect change [27]. This insight is particularly salient in contexts of disaster and emergency displacement, where individuals often face profound loss of control due to unpredictable and destabilizing events [7,14,45]. Forced displacement disrupts social, economic, and environmental systems, leading to acute shortages of resources and exposing survivors to a range of vulnerabilities, including unemployment, inadequate housing, food and water insecurity, and various forms of deprivation and discrimination [74,75]. It has also been observed that individuals who held leadership roles or elite status prior to displacement often emerge as de facto leaders within displaced communities, thereby preserving their relative privileges [76]. In other words, displacement frequently reinforces social hierarchies, creating a divide between those in leadership positions and the broader displaced population.

Displacement adversely affects the health of survivors, both mental and physical, by exacerbating preexisting conditions and contributing to a spectrum of short- and long-term health problems. These include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, substance abuse, infant mortality, child morbidity, and maternal and perinatal complications [7,45,77]. Nevertheless, robust social networks and collective community actions have been shown to mitigate many of these health consequences [25,78]. The experience of displacement thus underscores that health is a multidimensional construct, extending well beyond its biomedical definition.

Despite the relevance of the healthy community framework in these contexts, there remains a scarcity of studies applying this theoretical lens specifically to displaced communities. Most research concerning displacement and health tends to focus on medical and psychological outcomes [79,80], rather than on the ideological and theoretical underpinnings of the Healthy Community model as previously outlined. Those few studies that do engage with this framework among displaced people often emphasize health disparities and inequities (e.g., [81,82]).

In contrast, the concept of resilience has dominated scholarly inquiry into displacement [12,28,31,34,35,55,75]. Resilience is frequently invoked to explain how individuals and communities can cope and even thrive in the aftermath of extreme adversity. This emphasis is understandable: resilience is fundamentally associated with crisis response, adaptation, and recovery. However, while resilience addresses survival and immediate adaptation, the healthy community approach offers a more expansive and enduring vision. It reflects a sustained, inclusive ethos of well-being, grounded in collective empowerment, equity, and environmental and social sustainability.

Accordingly, this study positions the Healthy Community framework as a critical and underutilized perspective for understanding both the long-term recovery and proactive preparedness of displaced communities. It complements and deepens the discourse on resilience by emphasizing the systemic, participatory, and transformative dimensions necessary for sustained health and well-being in the face of displacement.

3.3. A Healthy Displaced Community: Beyond Resilience

Resilience is largely contingent upon pre-disaster preparedness and the existence of strong social capital, which is characterized by close interpersonal connections and effective interactions both within the community and between community members and the broader society [29,59]. It also encompasses post-disaster manifestations of social capital, such as social support networks and emotional exchanges, which have been shown to play a crucial role in facilitating recovery [11,77,78]. Communities that are able to organize and mobilize their social networks tend to provide survivors with more effective access to resources and foster collective action in addressing shared challenges [37,45,77]. As such, a resilient community is one that possesses strong social capital, along with the capacities and assets required to withstand, adapt to, and recover from disaster [83,84].

However, resilience is not uniformly distributed across all populations. Milofsky [30] critiqued the prevailing “before and after” framing of disaster resilience for failing to account for the social, economic, and geographic inequalities that render certain communities more vulnerable to harm. He argued that the benefits of resilience are not equally accessible and may in fact exclude marginalized and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. To address these disparities, Milofsky advocated for a resilience framework that explicitly confronts structural inequalities and emphasizes the principle of “building back better.” This emerging approach to resilience extends beyond mere recovery; it is envisioned as a pathway toward a more equitable and sustainable notion of a healthy community. Central to this vision is the cultivation of capacities that not only restore but also transform, potentially serving as levers for systemic change.

Although there are areas of overlap between the concepts of resilient and healthy communities, we argue that a clear distinction is necessary. The long-term, comprehensive, and inclusive social dimensions that define a healthy community are instrumental in fostering a higher degree of resilience. Healthy communities actively address and mitigate social inequalities, and as a result, they are almost always resilient. In contrast, resilient communities may emerge from exclusionary structures and are not necessarily healthy. A displaced community, therefore, may demonstrate resilience, but ideally, it should strive toward becoming a healthy community. This distinction is grounded in a twofold, interconnected rationale: first, the temporal nature of each concept, and second, the manner in which each addresses social disparities.

3.3.1. Crisis Response or Sustainable Development in Resilient Versus Healthy Communities

Resilient communities are primarily associated with crisis and emergency response. They emphasize adaptability, recovery from external shocks, and preparedness for unforeseen disruptions and disasters [31,85,86,87]. In contrast, healthy communities represent a broader, more comprehensive, and future-oriented paradigm. They are grounded in proactive efforts to promote long-term well-being and enhance the overall quality of life for all residents [68,73]. While healthy communities may include preventative measures—intervening before issues deteriorate [82]—their primary focus lies in fostering a shared vision for the future and engaging in collective actions aimed at sustained improvement.

In this regard, the healthy community approach to crisis preparedness encompasses resilience but also transcends it. Rather than focusing solely on immediate response and recovery, it seeks to generate lasting, positive change [26,68]. Unlike resilience frameworks that emphasize “bouncing back” or adapting to disruptions [85,86], healthy communities prioritize building durable infrastructures and systems. These efforts often include cross-sectoral collaboration that centers on residents and community conditions and promotes authentic and equitable citizen engagement.

As King [75] noted, definitions of resilience that focus on rebounding from disaster may obscure enduring structural inequities and the chronic, multifaceted nature of community trauma. Therefore, while resilience is a crucial component of community well-being, the healthy community model offers a more holistic and inclusive framework for addressing both acute crises and long-term systemic challenges.

3.3.2. Addressing Disparities by a Resilient Versus Healthy Community

This distinction between the approaches extends to how disparities are addressed by each of them. Scholars widely agree that the most vulnerable populations bear the highest burden and loss during disasters and displacement [7,60,74,78]. Disparities are evident in capacities and resourcefulness, access to essential resources, and even in unequal familiarity with and benefit from communal life prior to displacement. As individual resilience is often a reflection of the broader resilience of one’s community [31], marginalized individuals are often left to cope with crises on their own, lacking the social networks and capacities that facilitate collective recovery [84]. Disadvantaged groups may also remain in shelters longer than others and face limited access to aid and social support. They struggle to integrate into the host society as they experience socioeconomic gaps compared to natives [43,88]. Clearly, the stronger the social capital—the more resilient a community is [30,31,34,83,86]. But can resilience gaps be effectively addressed through crisis response measures alone? We assert that the answer lies in adopting a healthy community approach, one that facilitates resilience but also enables a profound process of strengthening the community, while prioritizing the reduction in disparities and the empowerment of those at the margins of society.

While some studies document successful interventions during emergencies that effectively empowered disadvantaged groups (e.g., [80]), for most vulnerable survivors, disasters are detrimental. Capacity building, inclusive citizen participation, and empowering strategies should begin well in advance, during routine times. Moreover, when emergency evacuation brings together people with diverse social capital sheltering under the same roof, there is always the risk that ‘elites’ social capital’ [37] will dominate, preventing the participation of the marginalized. Since resilience is unevenly distributed in community shelters, a resilient group may quickly revitalize by leveraging its strong social capital, resources, and networks, while marginalized populations—intentionally or not—may be excluded from recovery efforts, even when framed as ‘collective actions’.

In conclusion, a healthy displaced community bases its recovery efforts on the community as a collective social system. It acknowledges societal disparities and their adverse effects on health and well-being, striving for their elimination. By implementing long-term interventions, a healthy community prioritizes sustainable solutions. It enhances resilience as part of a larger and comprehensive process to build and strengthen social relationships among individuals and groups who congregate in the displaced community. Guided by core principles of participation, empowerment, and capacity building, a healthy community employs communal interventions and strategies to bridge existing gaps, including the resilience divide. In doing so, it leverages the power of community processes to better mitigate, prepare for, and address the psychosocial and physical challenges caused by displacement.

The next section discusses the critical role of community interventions in displacement and disaster recovery as a form of inclusive and collective strategy, which supports the vision of a healthy displaced community.

3.4. It Takes a Community Approach to Heal a Collective Upheaval

Displaced communities do not emerge instantaneously, nor are they always readily accessible to displaced populations. Individuals may arrive at disparate locations or shelters from fragmented communities, either as part of a group or independently. In some cases, connections form organically, while in others, individuals are placed together by external forces. Scholars have consistently emphasized that investments in social and community development—independent of physical infrastructure—significantly contribute to resilience and recovery [32,36,62,89].

Community-based interventions are widely recognized as vital for strengthening social capital and supporting the transition from crisis to resilience in the aftermath of mass trauma events [29,30,31,89]. While social capital is often treated in the scholarly literature as a relatively stable characteristic—varying in degree or form (e.g., bonding vs. bridging)—it is, in fact, a dynamic resource that can be cultivated and expanded through targeted interventions. Community-based initiatives can facilitate new connections among residents and foster relationships with public officials, thereby increasing trust, mutual support, and civic engagement. Such interventions have proven to be among the most effective strategies for fostering collective efficacy among individuals who have undergone shared experiences of collective trauma [45,64].

Community interventions may occur within the displaced individuals’ original communities as part of pre-disaster preparedness or emerge during post-disaster rehabilitation and recovery [11,35,59]. In both contexts, these interventions contribute to building community capacity by cultivating a sense of communal identity, restoring the idea of ‘home,’ and reinforcing social networks and cohesion [29,42,43,49,66]. According to Hobfoll et al. [45], interventions in the immediate and intermediate post-trauma phases should aim to promote a sense of safety, calm, self- and community efficacy, connectedness, and hope. Support groups and psychoeducational activities can serve as vital platforms for uniting individuals around shared local recovery efforts [43,45]. However, they are insufficient to bring about a community-wide change.

Reinstating routines, moreover, fosters a sense of continuity and provides a psychological anchor for rebuilding communal life [42,66]. The establishment of leadership structures and the delegation of roles and responsibilities empower displaced individuals to leverage internal capacities, utilize self-help strategies, and engage in mutual aid [36,37,60]. Conversely, the absence of meaningful participation opportunities can be profoundly disempowering [64]. Community interventions not only facilitate the development of effective social networks necessary for collective living [35,66] but also ensure that supportive mechanisms remain embedded within the community as long as these social structures and functions are maintained. Displaced communities that organize around these capacities, for example, through task-oriented committees—can actively engage other survivors and foster broader participation [47].

Milofsky [30] further underscores the importance of community-driven initiatives and inclusive engagement in challenging entrenched structural disadvantages. He emphasizes the need to enhance local agencies, support the emergence of grassroots leadership, foster more equitable interactions with external institutions, promote asset-based community development, and encourage collective learning. Most crucially, he advocates for the cultivation of sustained social capital and long-term community networks. These interrelated practices facilitate the transformation from vulnerability to resilience, laying the groundwork for equitable recovery and structural transformation.

Our discussion thus far highlights the fundamental discrepancies between displaced communities and those considered healthy or stable communities. While both contexts underscore the importance of resilience and prioritize communal over individual interventions, a critical question remains unresolved: Can a displaced community—characterized by loss and trauma—evolve into a healthy community?

4. Can Displaced Communities Be Healthy?

To explore the above question, we first introduce a conceptual model of a “healthy displaced community” and then analyze global case studies of forced displacement to identify the extent to which our model-defining features are present. To our knowledge, no existing studies have examined displaced communities through the lens of a healthy community framework. Furthermore, scholarly engagement with the healthy community approach has waned in the past decade. The foundational contributions of scholars such as Norris and Pittman [26], Minkler [25,90], and Wolff [27], including Wolff et al. [91], have not been sustained in the recent literature. Accordingly, this effort not only introduces a novel analytical perspective but also aims to revitalize academic interest in a valuable yet underutilized theoretical approach.

4.1. A Proposed Model of a Healthy Displaced Community

A displaced community, as previously defined, is one that shares unique ecological, social, and psychological characteristics shaped by the devastation of collective trauma and consequent displacement. The proposed model of a healthy displaced community integrates the specific needs and traits of a displaced community with the principles that define a healthy community. It complements a critical gap in published studies that neglects to address structural inequalities and chronic complex trauma faced by vulnerable populations who are [25,90more severely affected by disasters than others [75].

The model comprises three interrelated dimensions: (a) implementation of community interventions to address collective trauma, (b) empowerment of vulnerable and disadvantaged displaced populations, and (c) a long-term commitment to sustainability that transcends short-term resilience. Empowerment and sustainability are core principles of the healthy community philosophy [25,82,91], offering essential strategies to confront the systemic challenges that displaced communities face by fostering agency, inclusivity, and structural stability.

Community interventions: Extensive research supports community-based interventions as a primary strategy for addressing the needs of populations affected by collective trauma and displacement [28,29,30,31,32,45,92]. Similarly, healthy community approaches, which aim to challenge entrenched structural inequalities, emphasize and prioritize collective action and local engagement [25,27,71,90]. As previously discussed, communal interventions enhance social capital and resilience among displaced populations while addressing environmental challenges in temporary shelters and disaster-affected communities. However, disadvantaged groups—who often face more severe consequences from displacement—are less likely to participate in such activities, limiting their access to the benefits of these interventions. Therefore, targeted efforts must ensure that vulnerable populations are fully included, recognizing the imperative to correct systemic disparities through inclusive practices.

Empowerment: Displaced individuals commonly experience profound losses, diminished agency, and a pervasive sense of disempowerment—effects that are especially severe among the most vulnerable subgroups [37,60,74,81]. Empowerment is thus a vital dimension of a healthy displaced community, grounded in the premise that, without systemic reform and intentional corrective measures, meaningful recovery is unattainable. The ideal of a healthy community is to pursue equity and eliminate powerlessness [27,72,90], recognizing that persistent inequality undermines overall community well-being.

Community empowerment is an ongoing, participatory process rooted in the local community and grounded in the principles of democratic engagement. It aims to encourage the active involvement of marginalized groups in communal decision-making processes [93]. Through community empowerment, disadvantaged populations are enabled to gain greater control over the policies and activities that directly impact their lives [94,95]. The implementation of community empowerment is typically gradual and long-term in nature, as it necessitates sustained efforts in public education, capacity building, and empowerment training.

Although resilience frameworks call for inclusion and support of at-risk groups [75] empowerment is not a core tenet of resilience theory. Moreover, resilience is often correlated with strong social capital. This raises a critical question: Can marginalized and disenfranchised populations build social capital under the extreme conditions of displacement and recovery? Furthermore, when displaced communities “bounce back” only to return to the same adverse conditions they initially fled, trauma may deepen rather than heal. Milofsky’s [30] concept of “Building Back Better” aligns more closely with a transformative, corrective approach that addresses the inequities underlying displacement. Empowering interventions must therefore be designed with long-term goals in mind, fostering a collective vision for a just and inclusive future.

Sustainability: In this model, community interventions are not episodic responses to crises but are instead embedded as routine, long-term practices that extend across all phases of displacement. These include activities in temporary shelters, host communities, and return environments. Sustainable interventions ensure ongoing participation, foster community development, and strengthen long-term cohesion. Intentional strategies focused on marginalized groups are essential to ensure their inclusion and address the specific barriers that isolate them from broader community networks. Structural inequities cannot be redressed by intention alone. The healthy community approach offers a framework for creating a shared vision and building the capacity of communities to realize it [27]. Thus, the first two dimensions—community interventions and empowerment—are not only necessary for sustained recovery but also foundational to achieving an equitable, healthy society.

A long-term commitment to the healthy community model ensures that resilience is not an exclusive privilege of communities with pre-existing social capital. Instead, it promotes the equitable distribution of the very practices that strengthen social cohesion, integrating them into daily life and embedding them into the social norms and values of the community.

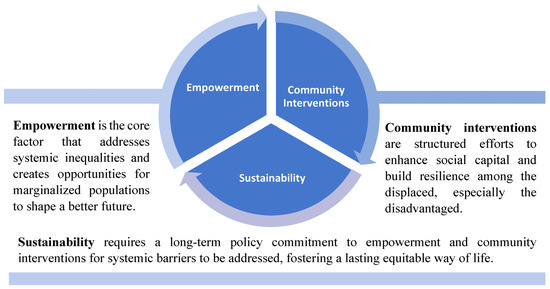

The three dimensions of the model for intervention with displaced communities to reach a state of a healthy community are presented in the following exhibit (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A proposed model of a healthy displaced community.

4.2. Exhibits of a Healthy Displaced Community Model in the Literature

The proposed model of a healthy displaced community presents an aspirational framework for addressing the deep and long-term impacts of forced displacement, extending beyond a resilience-based perspective. As a new framework designed to address the field of displaced communities, it is inspired by the healthy community approach.

While its principles are evident in international case studies, they appear in a scattered and fragmented manner rather than as a coherent continuum aligned with the rationale presented in this study. The model herein integrates three practical dimensions—community intervention, empowerment, and sustainability- which are rooted in the healthy community approach, but at the same time, they may correspond with displacement studies. The following review examines a sample of case studies of displaced communities to identify evidence of the model utilization. Assuming that it may be unlikely to find a single case study that fully encompasses all three dimensions, our goal is to demonstrate the model’s relevance and value through real-world examples, highlighting how these dimensions interact across different contexts.

Distinguishing between acute crises such as disasters, and chronic trauma such as poverty, King et al. [75] find that the vast majority of published studies on community resilience deal with disasters, whether from the perspective of preparedness or response. In their study, King et al. reinforced that resilience is not equitably distributed. They propose community interventions that enhance cross-sector collaboration—mobilizing comprehensive professional support while ensuring that interventions remain community-driven and center around its people. In several US cities, community interventions that promoted multi-sector collaboration were shown to strengthen community resilience in the face of long-term stressors and trauma. These interventions strengthened social networks and provided collective solutions to mitigate the effects of trauma. Multi-sector collaboration, which engages healthcare, the public sector, funders, and community-based organizations, aligns with the core principle of healthy communities, provided it is not imposed in a top–down manner but instead fosters true community development, ownership, and local leadership [91]. In this vein, King et al. [75] advocated for culturally sensitive approaches to coping and community-owned solutions, such as healing-centered community organizing and ‘indigenous ways of knowing’ [96]. Among Vietnamese refugees in the US, for instance, culturally informed coping strategies include a deliberate avoidance of discussing past trauma to prevent its transmission to younger generations [97].

A bottom–up, participatory approach to community interventions among disaster survivors and evacuees was also noted by Kwok et al. [98], who based their findings on a study in five urban neighborhoods in New Zealand and the US. They acknowledge challenges in engaging ethnic minorities and lower-income residents, suggesting that resilience interventions often favor those with stronger social capital, and that social capital is an asset largely shaped by one’s community of residence. Consequently, they emphasize the importance of assessing neighborhood conditions to establish realistic performance expectations for resilience initiatives. Resilience interventions are often short-term, making it impossible to amend deeply rooted societal issues. Therefore, Kwok and colleagues recommended complementing community-based interventions with individual and psychosocial strategies, alongside long-term government policies that ensure institutional support and financial stability for disadvantaged survivors. Although they did not adopt an equity-focused perspective or propose specific empowerment strategies, their findings align with our observations and underscore the value of a healthy community approach.

Driven by long-term planning, the Israeli government launched an emergency preparedness program in 2002 aimed at developing communal resilience teams, particularly in frontline communities near the borders. This national initiative of the Ministry of Welfare, known as Community Emergency Teams [99], mirrors similar emergency preparedness programs in other countries [11], all of which focus on enhancing communal social capital and equipping communities to better cope with disasters. However, while these initiatives are designed for the long term, they are not necessarily inclusive, and as a result, disadvantaged communities are underrepresented in such programs and remain unequally prepared for disasters. They are most likely also disproportionately affected when crisis occurs. The war that broke in Israel in 2023 following the October 7th massacre starkly exposed these disparities. Well-prepared communities, led by strong community emergency teams, swiftly transitioned their leadership to living in the displaced location, ensuring continuity in communal coordination, and restarting services such as children’s education. In contrast, communities without established local leadership became dependent on government services or the emergency teams of stronger evacuated communities with whom they shared shelter life [47]. Many reported gaining an appreciation for organized communal life and benefiting from participation in collective recovery activities. Studies on resilience in Israel further support the link between social inequality and levels of resilience [100]. While this case study underscores the importance of community-based interventions in strengthening resilience, it also highlights how these strategies often reinforce advantages for already well-resourced communities. Kimhi advocates for a multi-level approach that includes promoting personal psychological well-being, strengthening social networks and collective capacity, and fostering trust in institutions and governance to enhance societal resilience.

Another post-war case study from Sri Lanka highlights multiple disparities that hinder community resilience, including widespread poverty and unemployment, which exacerbate mental health issues, loss of homes, resources, and livelihoods that disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, and educational disparities that worsened due to displacement [80]. The study also identified culture and local norms as both risk and protective factors. For instance, military governance, gender-based violence and discrimination, and unwanted pregnancies were significant challenges, compounded by limited mental health services and cultural stigma surrounding them. From a protective point of view, while traditional Western interventions were found to be less effective, integrating cultural practices, rituals, and traditional beliefs empowered the local community to engage in collective healing, restoring a sense of belonging and shared identity. This community-centered approach facilitated a more relevant response to local needs, improving accessibility and increasing both the availability and utilization of support services. For example, training local residents in basic mental health interventions not only alleviated the strain on scarce service but also shaped a more culturally aligned approach rooted in traditional values. Conversely, when cultural traditions perpetuated trauma and systemic inequality, the authors recommended challenging and breaking down oppressive structures such as patriarchal suppression of women and rigid hierarchical systems like caste. When women were empowered to take control over their lives, they emerged as vibrant leaders within their communities. In accordance with the healthy community approach, systemic societal changes can foster empowerment, genuine participation, and collective transformation. The Sri Lanka case study underscores the necessity of sustainable planning, whereas short-term humanitarian aid proved insufficient. Finally, attending to economic instability and providing microfinance programs and vocational training helped rebuild local economies and reduce reliance on external aid. Hence, like Kimhi [100] in the Israeli case study, Somasundaram and Sivayyokan [80] also emphasized the importance of a multi-layered intervention, where individual support, communal interventions, and national policies enhance long-term and comprehensive impacts.

Healthy communities prioritize creating equitable conditions for engagement and participation, ensuring that efforts to restore justice are driven by those they aim to serve. Developing healthy displaced communities relies on local knowledge and the active participation of those affected by adversity. Those who experience the problem—must be part of the solution [45] to ensure that it is relevant, acceptable, sensitive, and attuned to local needs [26,81,101].

5. Discussion

Building a healthy community is a long-term process, let alone building a healthy displaced community. The analysis provided in this article explains the complexity of displacement and its debilitating impact on individuals, families, and groups. We juxtaposed displaced communities with the ideal form of healthy communities. We further explored the question of whether displaced communities can be healthy. To assess this, the article delineates the meaning of a ‘healthy community’, providing the historical background of this conceptual and practical framework for advancing inclusive community development. In particular, it sheds light on the rationale for linking the concepts of a displaced community and a healthy community, distinguishing the latter from resilience and demonstrating its relative significance, beyond resilience.

Our analytic examination of the two concepts and their interaction culminated in a proposed model of a healthy displaced community. This model comprises three interconnected dimensions: (1) community interventions that foster citizen participation and strengthen social networks, (2) the empowerment of marginalized displaced populations, and (3) a long-term commitment to a shared vision that ensures sustainability. The model is embedded in the assumption that displaced communities may be more resilient and encounter less harm if more members are better equipped to cope collectively. To conclude, the article presents a sample of case studies that illustrate how some elements of a healthy displaced community can be observed in practice.

In search for evidence of a healthy displaced community, numerous studies reflect the three dimensions of our proposed model across diverse global contexts: research on community interventions with disaster survivors and evacuees [11,98]; studies highlighting empowerment, given the disproportionate effect on marginalized populations [80,81]; and studies that stress the limitations of short-term interventions, advocating for long-term planning and sustainable development [31,37]. While these studies provide valuable insights into aspects of a healthy displaced community, the model proposed in this article integrates these aspects into a cohesive understanding and actionable recommendations.

This article contributes an innovative perspective on the interaction between displaced communities and healthy communities. It provides an integrative definition of a displaced community, which is missing in the current literature. While most existing studies on disaster and displacement focus on resilience as the primary framework [75], we argue that resilience alone is not enough. Resilience fails to account for the disparities and vulnerabilities exacerbated by disasters, which existed long before their onset and will persist, or even worsen, once short-term recovery interventions subside. These inequalities are deeply embedded in the structural problems of society. Resilience is a critical framework, often linked to the notion of ‘bouncing back’ and ‘bouncing forward’ [98]. More recent thinking introduced the idea of ‘building back better’ [30], emphasizing the need to address structural inequalities in order to reduce vulnerability and mitigate greater harm in the future. However, resilience is still largely associated with the short- and medium-term goals of preparedness and emergency response. The healthy displaced community framework extends this discourse by calling for the creation of lasting conditions that support sustainable social transformation, moving beyond crisis-oriented resilience.

The vision of a healthy displaced community may be perceived as idealistic or even unattainable. In fact, the ambitious nature of the healthy community approach itself may help explain its decline in academic and policy discourse. Emerging in the 1980s as a movement aimed at correcting systemic injustice, the healthy community framework rapidly expanded as a comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing complex societal problems. It transformed how the root causes of disparities were conceptualized, shifting the focus from individual shortcomings to structural inequalities. By emphasizing collective responsibility, the movement promoted empowerment, equitable participation, genuine inclusion efforts, and the fulfillment of a shared vision [24,27,68,72]. However, despite its initial momentum, interest in the healthy community approach has declined in subsequent decades, as reflected in the decrease in related publications. Aside from a handful of foundational works by leading scholars in the field (e.g., [25,26,27,90,91]), the prominence of studies associated with this approach has waned. Through our study, we seek to revive its relevance by applying it to the context of forced displacement.

Circulating back to the research question, and in light of the extensive analysis presented in this article, we argue that displaced communities can be healthy. However, achieving this is a comprehensive, complex, and long-term endeavor; one that demands ethical commitment. We live in an era where policymakers, funders, and researchers prioritize immediate, result-driven responses. Conversely, the healthy community approach is inherently broad and idealistic, making it more challenging to implement and even harder to measure in the short term. Achieving a healthy community, whether displaced or not, requires appreciation and patience with its demanding collaborative nature. A healthy community relies on collective action and the long-term empowerment of marginalized populations through inclusive community organizing. If systemic change and the alleviation of societal disparities were easily attainable, top–down strategies or individual-focused solutions might be sufficient. But, in fact, they are far from changing the status quo [91].

A healthy community has the potential to provide a fundamental response to some of the most profound challenges arising from forced displacement. However, reconciling the concept of a healthy community with the reality of displacement presents several challenges that must be acknowledged. First, the severe and immediate devastation of emergency displacement can obscure the very notion of health in this context. Secondly, the disproportionate impact on disenfranchised populations undermines the right-from-the-start drive for the equality associated with healthy communities. Third, the inherently idealistic, even utopian, nature of a healthy community may render it seemingly unattainable in a displacement context. Finally, the long-term, systemic, and comprehensive strategies required to create the necessary conditions for its realization may raise feasibility concerns and limit practical implementation.

The devastating effects of disasters on resources, social networks, and mental and physical stability can push individuals deeper into cycles of loss and inequality. Therefore, the effects of disasters must be addressed beyond survival, preparedness, and recovery. Building inclusive, ethical, equitable, and capable communities takes time. The healthy community approach provides a framework for doing so.

Displaced communities can be healthy, but only as part of a broader healthy society. While short-term interventions are essential for alleviating the immediate hardship of disasters and displacement, resilience alone is insufficient to address their lasting and compounding effects. As ancient wisdom says, society grows great when people plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.

6. Limitations

This conceptual study presents several limitations which must be acknowledged. Our claims are grounded in an analysis of the existing literature, without original empirical data. In assessing the proposed model, we examine its manifestation through a limited selection of global case studies, offering only a brief exploration of each. While our analysis of displaced communities is comprehensive, given the diversity, dynamics, and complexities of the phenomenon, our analysis remains broad and cannot fully capture its nuanced realities. Most importantly, we acknowledge that the very notion of a healthy displaced community is ambitious, perhaps even utopian. Some may view it as unrealistic, particularly in the context of disadvantaged populations, impoverished communities, and the Global South. However, it is precisely because of these challenges that we argue for the necessity of holding onto and advocating for this ideal vision of a healthy displaced community and what it entails to promote it. The easier choice is to relinquish it in the face of adversity.

7. Conclusions

Displaced communities face profound challenges that affect all aspects of life. While interest in these communities is growing, there have been few academic attempts to conceptualize them as a distinct social phenomenon. This paper first offers a broader understanding of what displaced communities are and how they might be supported. It then sought to revitalize academic discourse on healthy communities. Drawing on these two bodies of knowledge, the paper explored what is needed for a displaced community to evolve into a healthy one. Our review of the literature indicates that policymakers and scholars tend to focus primarily on resilience before and/or after a crisis. However, resilience represents only partial dimensions of a healthy community. A more integrated approach is essential, one that bridges the realities of both displacement and health. The analysis led to the development of a conceptual model of a healthy displaced community, grounded in principles of empowerment, community interventions, and long-term sustainability. A healthy community approach calls for holistic, pre-disaster strategies that enable displaced communities not only to survive, but also perhaps, to grow and evolve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and R.A.C., methodology, I.P. and R.A.C., investigation, I.P. and R.A.C., writing—original draft preparation, I.P. and R.A.C., writing—review and editing, I.P., R.A.C., H.N., L.M. and O.S.G., visualization, I.P. and R.A.C., supervision, R.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McAuliffe, M.; Oucho, L.A. (Eds.) World Migration Report 2024; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2024 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID). Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) Report 2024; UNOPS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://disasterdisplacement.org/resource/grid-2024/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- International Organization for Migration IOM. Glossary on Migration; International Organization for Migration IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hirsh, H.; Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. A new conceptual framework for understanding displacement: Bridging the gaps in displacement literature between the Global South and the Global North. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, R. Development and displacement in the Black community. J. Health Soc. Policy 1990, 1, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Libuy, M.; Moreno-Serra, R. What is the impact of forced displacement on health? A scoping review. Health Policy Plan. 2023, 38, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, P.; Steger, M.F.; Bentele, C.; Schulenberg, S.E. Meaning and posttraumatic growth among survivors of the September 2013 Colorado floods. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Koyama, Y. Relationship between psychological factors and social support after lifting of evacuation order in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.C.; Pavlacic, J.M.; Gawlik, E.A.; Schulenberg, S.E.; Buchanan, E.M. Modeling resilience, meaning in life, posttraumatic growth, and disaster preparedness with two samples of tornado survivors. Traumatology 2020, 26, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social capital and community resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, A.; Rana, I.A.; McMillan, J.M.; Birkmann, J. Building community resilience in post-disaster resettlement in Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2019, 10, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vine, M.; Greenwood, R.M. Cross-group friendship and collective action in community solidarity initiatives with displaced people and resident/nationals. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1042577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Rockstrom, J. Social-ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 2005, 309, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnard, A.M.; Sapat, A. Population/community displacement. In Handbook of Disaster Research, 2nd ed.; Rodriguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Lemessa, D. Socio-cultural dimensions of displacement: The case of displaced persons in Addis Ababa. Afr. Study Monogr. 2005, 29, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verme, P.; Schuettler, K. The impact of forced displacement on host communities: A review of the empirical literature in economics. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 150, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.O.; Ferrara, A. Consequences of forced migration: A survey of recent findings. Labour Econ. 2019, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leus, X.; Wallace, J.; Loretti, A. Internally displaced persons. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2001, 16, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, S.; Jaafar, W.; Rosnon, M.; Khir, A. Role of community development on marginalized internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Borno State, Northeast Nigeria. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuday, J.J. The power of the displaced. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2006, 15, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, R.M.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Selvarajan, S.K. Subjective well-being, social network, financial stability and living environment of the displaced community: Implications for an inclusive society. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2024, 16, 1–12. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_ajstid_v16_n3_a370 (accessed on 2 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rose, K. (Ed.) Displaced: Literature of Indigeneity, Migration, and Trauma; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lackey, A.S.; Burke, R.; Peterson, M. Healthy communities: The goal of community development. Community Dev. 1987, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare, 3rd ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, T.; Pittman, M. The healthy communities movement and the coalition for healthier cities and communities. Public Health Rep. 2000, 115, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, T. The Power of Collaborative Solutions: Six Principles and Effective Tools for Building Healthy Communities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P. Social capital in post-disaster recovery. In Resilience and Recovery in Asian Disasters; Sothea, O., Yasuyuki, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, B. A review of the literature on community resilience and disaster recovery. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milofsky, C. Resilient communities in disasters and emergencies: Exploring their characteristics. Societies 2023, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. A conceptual framework to enhance community resilience using social capital. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2017, 45, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootle, D. Disaster recovery in rural communities: A case study of southwest Louisiana. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2007, 22, 2. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol22/iss2/2 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Cnaan, R.A.; Milofsky, C. (Eds.) Handbook of Community Movements and Local Organizations in the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ludin, S.M.; Rohaizat, M.; Arbon, P. The association between social cohesion and community disaster resilience. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyles, L. Community organizing for post-disaster social development. Int. Soc. Work 2007, 50, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhee, V.; Bohara, A.K. Social capital, trust, and collective action in post-earthquake Nepal. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 1491–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.G.; Van der Boor, C. Enhancing the capabilities of forcibly displaced people: A human development approach to conflict-and displacement-related stressors. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S. Post-domicide artefacts: Mapping resistance and loss onto Palestinian house-keys. Cult. Stud. Rev. 2016, 22, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridarran, P.; Keraminiyage, K.; Amaratunga, D. Building community resilience within involuntary displacements by enhancing collaboration between host and displaced communities: A literature synthesis. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress, Tampere, Finland, 1 June 2016; Tampere University of Technology: Tampere, Finland, 2016; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Benhura, A.R.; Naidu, M. Invisible existence. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helly, H.; Efrat, E.; Yosef, J. Spatial routinization and a ‘secure base’in displacement processes: Understanding place attachment through the security-exploratory cycle and urban ontological security frameworks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 75, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Ma, H.; He, H.; Yu, X.; Caine, E.D. Characteristics of Wenchuan earthquake victims who remained in a government-supported transitional community. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2013, 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lain, J.; Yama, G.C.; Hoogeveen, J. Comparing Internally Displaced Persons with Those Left Behind: Evidence from the Central African Republic; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]