1. Introduction

Political decisions shape architectural and urban spaces. Design, in turn, carries its own political ramifications for communities. This article examines how a single physical setting selectively filters individuals based on their embodied circumstances, with a particular focus on gender.

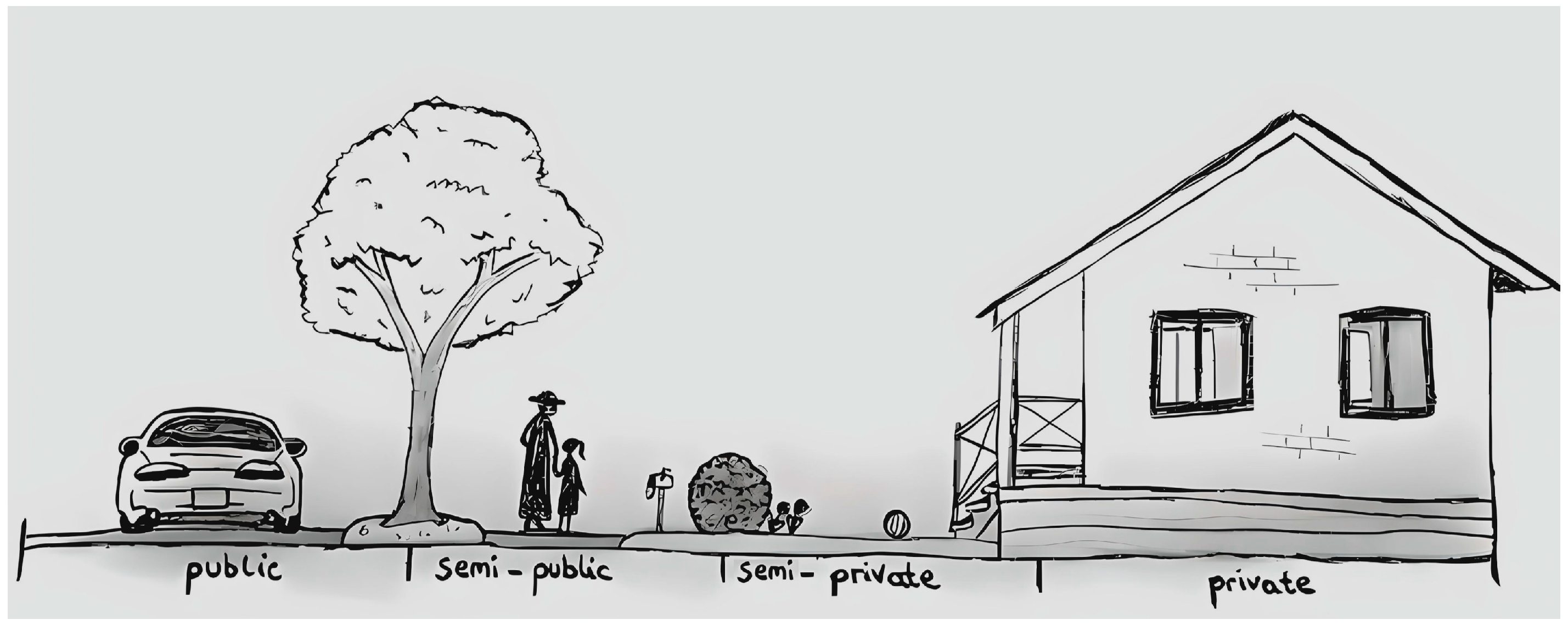

Today, it is generally acknowledged that architectural form selectively regulates movement. A clear example is “anti-homeless” armrests on benches that prevent lying down [

1]. More subtly, elements like decorative walls, elevation shifts, tiling changes and ornamental shrubs mark private space, signaling that an area is “under the undisputed influence of a particular group” [

2] (pp. 2–3). These cues make outsiders feel unwelcome and increase their conspicuousness to proprietors (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Recent research highlights how these tacit boundaries are especially restrictive for those who are physically or psychologically depleted [

3]. The explanation for this outcome weaves together several lines of scholarship. To start, people perceive environments in terms of action possibilities—what ecological psychologists call affordances [

4,

5,

6]. Additionally, research shows that hills and stairways appear steeper and more distant to those burdened by energy-depleting factors such as heavy backpacks, low blood sugar, fatigue, sadness, financial stress or inclement weather [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. By similar reasoning, latent territorial markers likely appear more severe to individuals who are physically or mentally exhausted, such as the unhoused or those who are politically and economically worn out. This makes latent territorial markers in urban space selectively permeable, a claim supported by observational studies [

3,

13,

14,

15].

The idea of selective permeability is, in many ways, obvious. In the 1940s, Erich Fromm got close to the outlook when he observed that the “environment is never the same for two people, for the difference in [their] constitution makes them experience the same environment in a more or less different way” [

16] (p. 61). Besides this, most already accept that infirmities can make urban settings less accessible (see

Figure 3). This is just as a city space can be more threatening to a woman than a man. Still, it is important to ask whether certain design features—although harmless in isolation—become selectively problematic in social contexts where women face sexual or other forms of aggression or simply have different needs than men. Restrooms are a clear example of the latter [

17]. Another issue is that design can reinforce gender norms and, as a result, selectively burden women [

15].

A core aim of this study is to deploy the selective permeability model—grounded in affordance theory—to articulate how urban structures shape women’s experiences by imposing constraints that often differ from those faced by men. The chosen framework draws on insights from value-sensitive design [

18,

19] and architectural practices that use implicit territorial markers to regulate movement [

2,

20,

21]. A second task is to present empirical evidence of gender-related selective permeability, based on qualitative data from focus groups and individual interviews. The findings suggest that factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and visible markers of religion intersect with gender to shape the selective presence—or absence—of obstacles. The surrounding culture also plays a role: for instance, a Black woman may encounter different barriers depending on whether she is interacting with locals in Paris or Seoul. These differences reinforce the selective permeability view that access and exclusion are not fixed properties of space but relational, varying with the individual’s embodied and social position. These shifting features can nonetheless be as real as the impediment that a staircase poses to wheelchair users.

Rooted in affordance theory, which was first developed by James Gibson [

4,

5] out of antecedents in Gestalt psychology, pragmatic philosophy and phenomenology, the selective permeability framework offers several advantages. One of its merits is that it provides a basis for demonstrating how environments objectively impose greater coping burdens on women than men, obviating the stereotype that women’s spatial concerns are merely emotional overreactions. Gibson’s concept of negative affordances [

4,

5]—defined as environmental features that severely restrict freedom of movement and impose harm—helps quantify this disparity: women often encounter more such barriers in shared spaces than men, though men face their own challenges, especially in certain intersectional contexts (e.g., Black men interacting with police in Western jurisdictions). Crucially, this uneven dynamic both reflects and reinforces broader gendered power structures. Building on these insights, this article argues that urban landscapes embody political affordances—material configurations that reflect and perpetuate societal inequalities. If this makes negotiating settings more exhausting, then—according to research already cited—obstacles become even more severe. Mapping these selectively present, negative and politically charged affordances may inform more gender-sensitive urban design standards.

At the same time, an affordance-based model is a reminder that, despite differences, people are similarly embodied and, thus, face comparable environmental constraints. Such a perspective is vital in discussions of intersectionality, where the risk is overemphasizing experiential divides to the point of suggesting that mutual understanding is impossible. Granted, men are systematically blind to the threats women face in urban venues, but many problems are recognizable to people of any gender once they are highlighted. The framework balances difference (in how selective permeability operates) with commonality (shared affordances), offering a path for meaningful dialogue on equitable design.

2. Selective Permeability, Normative Pressures and Affordances

Gibson posits that affordances—environmental possibilities of action—are directly perceived through energy patterns and chemical information (light, heat, sound, food sugars, etc.) [

5]. Crucially, he also hints that cultural practices and tools mediate these affordances, altering their availability [

5] (Chapter 8). These twin propositions—direct ecological perception and culturally modulated access—form the bedrock of the selective permeability model. In what follows, particular emphasis falls on the second aspect (culturally modulated access to affordances). This can be seen as being at odds with Gibson’s direct perception approach. Yet a case will be made that the direct perception view does not necessitate the premise that affordances are in all instances registered in energy and chemical arrays. Discussing these matters will set the stage for the account of gendered urban experiences developed in the next section and later supported by empirical data.

Although tension exists between Gibson’s views and cultural accounts of affordances, several illustrations align with his perspective. Comparative studies show that Korean and Western populations exhibit different stride patterns [

22], which may affect energy use and, in turn, perceived accessibility across distances [

23,

24]. In settings where chopsticks are the only eating utensil, proficiency or ineptitude with them alters the range of available affordances [

23,

24]. Likewise, the biomechanically distinct “Asian squat” (

Figure 4) supports postures and social uses of space that many Westerners find inaccessible [

23,

24]. These cases show that culture conditions embody action possibilities, making venues selectively permeable without contradicting direct perception theory.

While the preceding examples fit within Gibson’s framework, his theory does not fully account for how cultural norms generate social pressures that constrain behavior, an idea explored by more recent scholars like Joel Krueger [

25], Tibor Solymosi [

26] and others, e.g., [

27,

28,

29]. Indeed, Gibson might exclude such pressures from his definition of affordances, as they often emerge through temporally extended social gestalts rather than being directly specified in ambient arrays (e.g., optical, acoustic, chemical or infrared information). Nevertheless, selectively permeable social barriers—like those governing urban access according to gender—exhibit key characteristics of what Gibson terms negative affordances: they present objectively burdensome (not merely perceived) constraints that individuals must navigate.

To review, Gibson equates “affordances” with non-subjective “values” [

4] (p. 285). He explicitly asserts that an environment is not neutral but carries potential “benefits and injuries,” in other words, “positive and negative affordances” [

5] (p. 137). In a sense, both positive and negative affordances limit action. For example, a city sidewalk offers the benefit (a positive affordance) of enabling travel from point A to B, yet it also constrains actions since the path does not permit movement in any direction. However, if a pedestrian perceives and avoids a negative affordance, such as a threatening figure ahead, the situation more severely curtails options. A negative affordance accordingly operates dually: it presents (1) an objective hazard, that is, a risk of a negative outcome, and (2) it negatively impacts (reduces) behavioral freedom.

A noteworthy aspect of Gibson’s framework is his characterization of affordance theory as radical precisely because it treats environmental “‘values’ and ‘meanings’ as directly perceptible” [

5] (p. 127). Though agent-related, he distinguishes affordances from subjective impressions. In his own words, “these benefits and injuries, these safeties and dangers, these positive and negative affordances are properties of things taken with reference to an observer but not properties of the experiences of the observer” [

5] (p. 137). As a philosophical realist, Gibson insists that affordances—though dependent on an individual’s capacities—remain in a setting regardless of whether anyone is there to use them. Seen thusly, sidewalks and stairs have properties that afford strolling or climbing, even with nobody there to exploit them [

30].

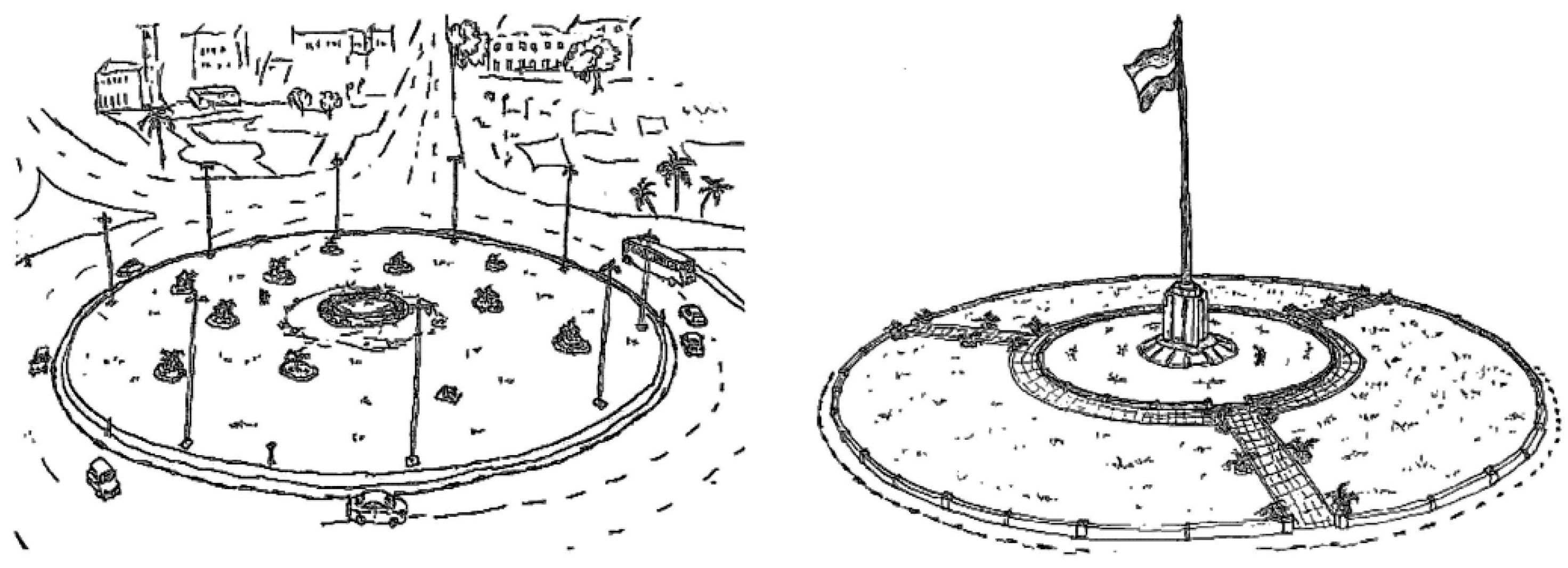

Gibson’s views are consistent with an additional point, which has been introduced already but is worth elaborating on. This is that variations in individual embodiment (e.g., health, tools, cultural habits) can alter susceptibility to environmental pressures, leading people to encounter disparate affordances, making settings selectively permeable. As mentioned at the outset, psychology experiments indicate that sadness, hunger, illness, tiredness, indebtedness, heavy backpacks and bad weather—in short, anything that depletes energy—make hills and stairs look steeper or farther away [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Architects and urban planners exploit these effects by including ornamental shrubs, minor elevation changes, and other additions that symbolically cordon an entrance to a building complex. Ethnographic work shows that such features disproportionately repel exhausted unhoused populations, compared to affluent visitors, who are in fact typically more welcomed and valued in these spaces [

3]. A parallel example can be seen in the 2015 modifications to Cairo’s Tahrir Square (

Figure 5), where decorative curbs and other tacit barriers were installed following the military’s removal of Mohammed Morsi—an event that followed Egypt’s 2011 Revolution. These design elements appeared more imposing and unwelcoming to politically and economically strained locals than to tourists, who were indeed less likely to face police harassment in the area [

14].

One may say, then, that Tahrir Square and many other urban structures are delineated by political affordances, defined as normative openings and closures that regulate human movement along demographic lines, often implicitly [

24,

31]. Remember, here, that Gibson equates affordances with values. These are embedded in artifacts, which are made and deployed for various purposes, as value-sensitive design proponents have argued [

18,

32,

33]. Consider, for example, why a bank may have polished wood paneling, marble floors, a high ceiling and ornamented columns. One reason is that those running it may want the venue to express the values of reliability, wealth and power [

32,

34]. This may invite affluent people in more than those of modest means, who are usually less welcomed and valued. The setting may also be more empowering to bank employees than to loan applicants [

13,

34] (see

Figure 6).

The upshot is that, without physically preventing access, urban areas can selectively regulate certain cohorts by discriminately imposing antagonistic pressures that are functionally akin to—or the same as—action-closing negative affordances. These patterns manifest across scales, whether in past racist seating restrictions that Rosa Parks confronted on Montgomery buses or in everyday prohibitions against sipping from a stranger’s cup in a café [

24,

35,

36]. Social prescriptions exist independently of any single human, which is one realist criterion. Another is that infractions have real consequences that range from imprisonment to ostracization to bodily harm, and most individuals immediately register this, even if prescriptive norms are not directly conveyed through energy or chemical arrays. For all these reasons, the selective permeability model (and political affordances) align fairly well with Gibson’s realist commitments.

Of course, Gibson does not offer the final word, with enactive cognitive science standing as a more recent embodied view. Though its founders are at pains to differentiate themselves from Gibson [

37] (Chapter 9), it has been argued that they massively overstate the divergence [

36]. Still, enactive views are worth attending to for two reasons: (1) because they give somewhat more emphasis to the role that human players have in building their worlds, and (2) because reconciling enactive standpoints with Gibson’s framework underscores the realism of social constructions.

Enactivism asserts that a minded agent does not mentally represent properties that pre-exist in a setting but instead brings forth—or enacts—worldly attributes [

37] (p. 9) that have “no non-experiential, physical counterparts” [

37] (p. 166). Thus, the originators of enactivism favor constructivism over Gibson’s realism [

37] (Chapter 9). However, constructivism need not negate realism—at least insofar as socially constructed conditions can selectively present negative affordances that exist not merely in the mind or a single individual’s interaction with a setting, but in the shared environment itself [

36,

38]. For example, Egyptians may amplify a hostile or ominous atmosphere in Tahrir Square through their cautious behavior—behavior that may, ironically, make them more conspicuous to police—just as a depressed mood may emerge when somber individuals struggle to move forward [

39,

40]. Likewise, if a woman’s apprehensive demeanor in a dangerous urban area makes her more of a target (much like how acting like a tourist may attract touts), then she objectively contends with a greater abundance of negative affordances. In this case, the locale and broader norms making the space oppressive to her exist independently of her. Consequently, one should not blame her comportment for her vulnerability but rather recognize that she navigates an institutionalized situation that is selectively hostile to her [

41]. In the same way a wheelchair user does not personally construct an area’s inaccessibility, the woman faces dangers that are really in the world.

3. Selective Permeability, Political Affordances and Gender

An argument has been that human-designed systems frequently function as demographic filters, selectively enabling or restricting access based on race, class, age and gender. This phenomenon manifests in both overt and subtle ways. For example, affluent communities have opposed subway extensions—interpreted in critical commentary as an attempt to prevent lower-income minorities from entering wealthy neighborhoods [

42]. Similarly, New York City planner Robert Moses purportedly engineered low overpasses to block buses—which Black residents have historically relied on—from reaching Jones Beach [

43]. Other tactics include the installation of pink lighting (which exacerbates skin blemishes) and ultrasonic “mosquito” devices (inaudible to most adults but irritating to young people), both installed to deter adolescents from congregating in certain urban settings [

13]. Gendered oppression—and, hence, exclusion—is widely operative and ranges from sexual assault in public spaces to transit systems that align more with men’s demands [

44] to bus drivers who open only the front doors “to see the pretty girls twice” [

45] (p. 251). This section discusses gender-based selective permeability and expands on the notion of political affordances. The subsequent section will present supporting qualitative data.

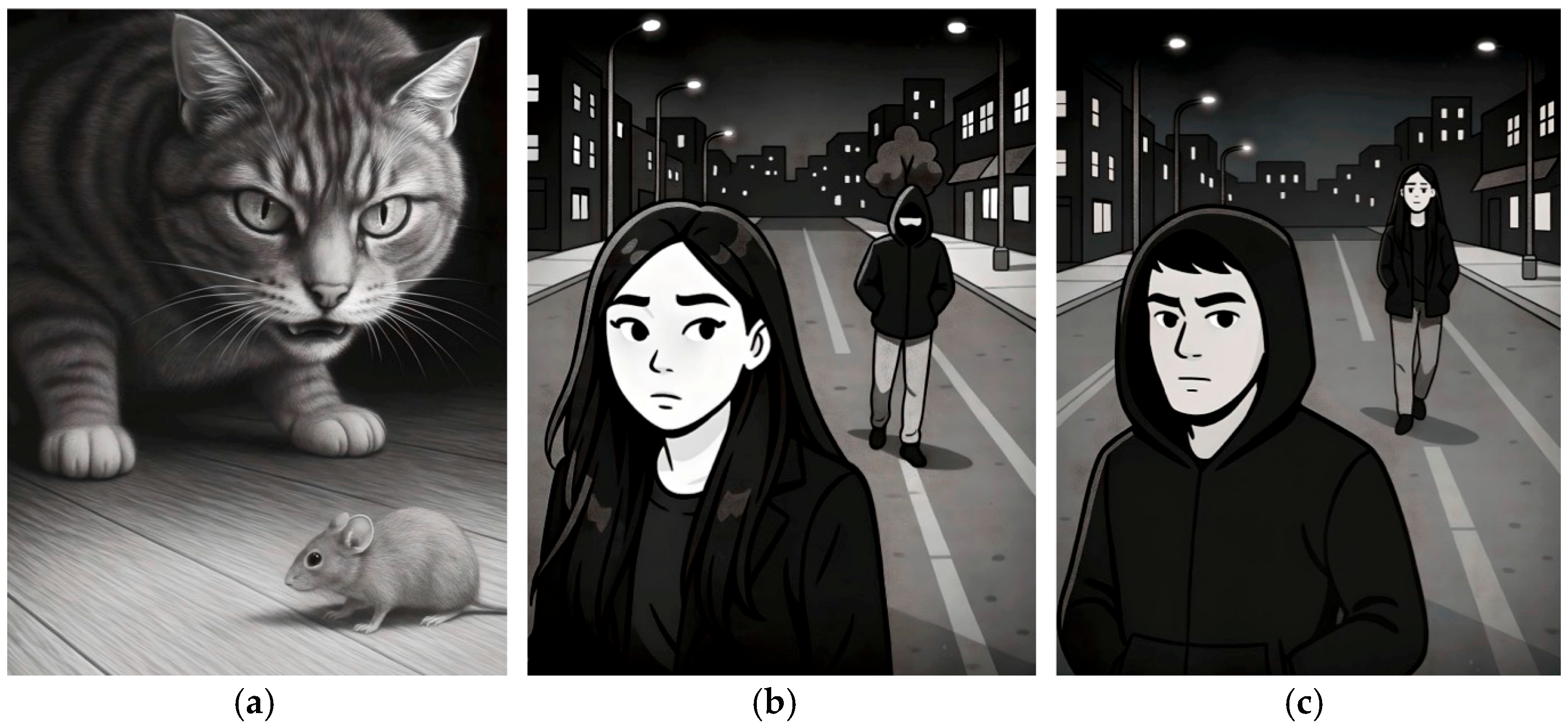

There are several justifications for the use of the term political affordances. First, Gibson equates affordances with non-subjective values, such as safeties and dangers. He accordingly suggests that predators are negative affordances to prey animals [

4] (p. 146). So, when women, for example, contend inordinately with sexual predation, they disproportionately encounter negative affordances in Gibson’s sense (see

Figure 7). Second, negative affordances that are customarily and selectively imposed on women reflect the conventions of a given polis or community and can, therefore, be designated as political. Third, these negative affordances are political because they reinforce values held within a particular polis. There are many documented cases—some already mentioned and others to be outlined—where mobility is especially limited [

46,

47,

48]. These selective barriers materially instantiate sexist ideology that, among much else, holds that women are naturally more passive or should stay at home more than men [

49].

While feminist scholars only occasionally employ the language of affordances, their work consistently challenges the notion of neutral environments by highlighting how physical and social structures disproportionately constrain women’s access and mobility. Consider how high heels amplify negative affordances for women [

24,

50,

51], who tend to perceive stairs as steeper than men do [

52]. While average height may contribute to this perception, some argue that even women wearing sneakers, by virtue of regularly accompanying those in heels, may habituate to shorter or more cautious strides. This would subtly yet objectively modulate the accessibility of various destinations, leading some to view stairs as less viable and instead opt for elevators or escalators [

24,

50,

51], a point supported by experimental and observational research [

52]. Other barriers include spaces unequipped for menstruation [

17] and transit systems that ignore caregiving logistics, which often fall on women [

44], plus a host of movement-restricting safety concerns.

Ecological psychologists frequently discuss how chairs afford sitting. Yet they rarely consider public restrooms and affordances for sitting, squatting or other functional features in these spaces, which are so often designed by men who overlook aspects of women’s experiences. As Greed explains:

Space within the cubicle is so limited that the edge of an inward-opening door often touches the outer rim of the toilet pan. Women have to get into the cubicle, close the door, and then do a three-point turn to position themselves over the toilet seat. There is usually a giant toilet-roll holder located directly above the toilet pan, so that women need to do a limbo dance to sit down. Such an arrangement could only be designed by front-facing urinators (male sanitary engineers). In comparison, in the USA, cubicles (stalls) are more generous in terms of internal floor space… But privacy is often limited in North American toilets because of the huge gap under the door and vertical gaps at the sides. These gaps were originally introduced to discourage male homosexual activity within toilets, with little regard to women’s privacy and embarrassment [

17] (p. 138).

In addition to gender-based biomechanical differences in urination, public toilets—along with schools, bars and alleys—are high-risk zones for sexual violence against women in some regions [

53]. The result is a landscape of negative affordances that disproportionately burdens women.

Regarding transit systems, turnstiles are often poorly designed for people with children or bags [

44]. While older token systems accommodated many commuters reasonably well, they posed challenges for a parent—typically a mother—navigating multiple stops for school, shopping and medical appointments for children [

15]. Such infrastructural choices are political, generating more negative affordances for women. Compounding this, women are also more likely than men to experience sexual harassment or assault in transit spaces, leading many to avoid initiating contact with strangers due to the risk of unwanted advances [

54]. As a result, women may feel compelled to take more complex routes, remain at home or forgo work and educational opportunities altogether [

44]. The implication is that women, on average, face a broader array of negative affordances, though, as noted earlier, men may also encounter their own.

Encounters may be shaped by lingering gazes, which can undermine women’s sense of safety and hinder their movement through urban spaces [

55]. For example, the jovial faces of revelers in a pub district may take on slightly threatening tones as night falls, especially for a woman, who faces greater danger than a man (see

Figure 8). She is caught in an unsettling public mood, not merely sensing a mood within herself. That is, she finds herself amidst what some urban commentators refer to as an atmosphere [

31,

56,

57,

58]. (The idea is also typified in

Figure 7 above, where the disquieting timbre in image (b) is not from the man alone but a product of the overall scene.) While some frame this phenomenon as subjective [

55], it may be better understood as akin to an affordance—negative in this case—emerging from the venue’s relational dynamics [

31,

56,

57,

58]. To the extent that the situation justifies the woman’s vigilance, the revelers’ contextually inflected expressions contribute to that atmosphere, regardless of whether any individual is overtly threatening.

From an enactive cognitive science perspective, the atmosphere is generated by the woman’s vulnerable embodied situation, much like how a depressed person genuinely experiences the world as more taxing due to their condition. But in this case, the woman is rendered vulnerable by the men’s gazes, intoxication and public rowdiness. Men behaving this way may themselves become negative affordances—features of the environment that contribute to a threatening atmosphere, which pronounces itself to the woman. As noted earlier, if the woman has reason for concern and moves hesitantly, she may become more of a target, much like a befuddled tourist drawing attention from touts. Thus, while the ominous atmosphere is a co-constructed product of multiple environmental dimensions and the aura is most palpably encountered by the woman, it remains real: an overarching negative affordance for her [

31,

57,

59].

From what has been said, a few summative points follow. To begin with, fear functions as a form of social control over women’s use of urban environments [

60,

61]. This is not merely because women may be persuaded to curtail their travel or behavior in public spaces out of fear; it is also because a fearful attitude may make them more tempting targets. The data—which will be presented next—further suggest that a dangerous space can become even more hazardous for women as their numbers in it dwindle, compounding the issue just mentioned. It is clear, then, that settings are shaped by embedded gender norms that influence how women navigate and experience them. All these points, along with others raised in this section, reinforce an assertion made by both feminists [

62,

63] and Gibson [

5] (p. 140): lived space is not genuinely neutral. For Gibson, this is because everyone encounters opportunities, safeties and dangers in a venue. Feminists add that women usually encounter different prospects and problems than men, in line with the selective permeability model and the related notion of political affordances. Therefore, as multiple researchers have noted, if the goal is to build increasingly inclusive cities, then a crucial step is recognizing that a given place typically does not meet the needs of all people [

64,

65,

66,

67].

4. Method and Results

This section presents qualitative data that supports, refines and elaborates on the account of gender-based selective permeability developed so far. The data further indicate that intersecting factors—such as ethnicity—amplify or mitigate the number, severity and kind of negative affordances women encounter.

Given that the data consist of a qualitative sampling (N = 56) of women’s experiences—often tied to highly localized contexts where crime statistics are unavailable and many issues go entirely untracked—the findings are not definitive. Instead, they are better construed as illustrative of some difficulties women confront. However, such limitations are common in cultural research—whether qualitative or quantitative—since results vary depending on how data are parsed, the number of parameters measured, the intersectional identity of respondents and personal factors that lead some but not others to opt into a study. Outcomes also depend on where participants live and the norms of their peer groups, not to mention the time period of the investigation, given that cultures evolve, sometimes rapidly. Crucially, the selective permeability model itself emerges in part from the recognition that definitive generalizations often fail to hold, or at the very least, require careful qualification according to extremely particular circumstances.

The qualitative data come from in-person interviews, conducted either individually or in groups, using a simple prompt: participants were asked to describe features that made certain places feel safer or more welcoming, and others feel less safe or more hostile. While respondents were neither encouraged nor discouraged from discussing intersectional factors, many spontaneously reflected on their own religion and ethnicity, as well as those of communities they had encountered in cities, often across multiple countries. For privacy reasons, conversations were not recorded; instead, interview teams—composed of women—took notes by hand. Some participants also chose to provide written accounts of their experiences (N = 9). Interviewees included a mix of local and international students, staff and faculty at a Korean institution, all of whom volunteered their time. No compensation was provided. All participants were fluent in English, with interviews conducted in that language unless Korean was preferred.

The interviewees came from many regions, including Central Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Latin America, North America, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Russia. Some respondents had complex identities, such as Korean-Russian, British-Somali or South American with Indigenous and European heritage. As mentioned, many had experience living in cities across multiple countries, which enabled them to offer informative comparisons. The aim—once more—was to sample women’s impressions of what they find inviting or hostile, threatening or safe in urban environments. Given the diversity of respondents, the reporting of results attends to the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of both the participants and the communities they engaged with.

An overriding observation from participants—striking for its obviousness yet still unexpected—was that, more than any aspect of infrastructure, the most threatening feature of urban environments for women is the presence of men. This is not to imply that all men are dangerous, nor to dismiss the influence of design and environmental factors. On the contrary, respondents pointed to specific characteristics—such as street layout, subway seating arrangements and time of day—as either aggravating or mitigating risk. Places like gyms, nightclubs and areas frequented by intoxicated men were often cited as particularly problematic. The role of city infrastructure in shaping women’s experiences of safety will be discussed in more detail after first highlighting key intersectional insights drawn from the data.

To start, consider the reflections of a Central Asian participant, who observed that street harassment in cities in her home country appears to correlate negatively with a woman’s perceived socioeconomic status. Her reason for thinking this was that she had observed that driving a more expensive car appeared to reduce the likelihood of a woman suffering sexual harassment. Might this be because wealthier women attract more intervention from police or bystanders? Does class bias also render them slightly more “off-limits” to potential harassers? While additional factors are undoubtedly at play, there is evidence that police and media tend to be less responsive to violence against certain disproportionately targeted marginalized groups, for example, Indigenous women and sex workers in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside [

68,

69].

A second Central Asian, residing in the greater Busan area of South Korea (henceforth Korea), discussed parts in that city with bars frequented by Russian men. Her observation—made very delicately—was not that Russians are generally prone to harassing women. Rather, she reported that the likelihood of encountering a few individuals engaging in such behavior was typically higher in areas with intoxicated Russians compared to neighborhoods with drunk Koreans. Several others of diverse backgrounds—including European, Korean and Latin American—similarly reported never being verbally harassed or groped by Korean men in public streets, though some recounted being stared at or followed.

Before continuing with the results, it is important to clarify that none of this suggests sex crimes are rare in Korea. Rather, it highlights how such crimes are often carried out, typically by perpetrators operating outside full public view or in situations ambiguous enough to make it difficult for women to confront assailants or report them to authorities. More will be said about this in the discussion section, with relevant literature reviewed. It is also worth noting that, in addition to unwanted stares and being followed in urban settings, two foreign respondents recounted sexual assaults: one described being forcibly kissed in the semi-private setting of a nightclub; the other reported a shoe store clerk touching her intimately in a way that she and an accompanying friend perceived as deliberately staged to appear accidental. A third participant remarked that some Korean men may see foreign women as “easier to experiment with [sexually], which is extremely reducing”—a sentiment echoed by a fourth woman.

Another respondent reflected on her experiences in London, England. “As a Black Hijabi woman,” she explained, “and due to the multicultural nature of London, I haven’t personally experienced overtly negative treatment for the most part.” Still, she noted that wearing a hijab makes her more visibly identifiable as Muslim than most men of the same faith—a concern that intensified when leaflets promoting “Punish a Muslim Day” were circulated in London in 2018. She observed that her “fairer… skin tone” might offer some protection and added that Black men may face greater hostility. In other words, Black men tend to encounter certain negative affordances that women sometimes avoid, though she did not, of course, deploy Gibson’s vocabulary. As she went on, “My younger brother has faced many forms of discrimination and microaggressions.” She recounted a time when her mother gave him a bank card to make a purchase, and the cashier questioned him aggressively, implying he had stolen it. Although she and her brother share a similar complexion, she doubted she would have been treated the same way. While the cashier may have noticed a gender mismatch in the name on the card, such details are rarely scrutinized, and it is questionable whether the cashier was even familiar with the gender-based naming conventions of her family’s East African background.

Another participant, who identified as “a young Black queer woman born and raised in France,” stressed that “my experience in cities in my country and abroad is obviously nothing like that of a white old straight man.” She noted, however, that in her mother’s country, Burkina Faso, she receives “privileged treatment” because many there regard her as white due to the lighter complexion she inherited from her French father. By contrast, many in Europe see her as Black, and there she has encountered “non-Black people… making racist jokes or even threatening or insulting me verbally.” She added that people often disparage urban areas with large populations of immigrants or their descendants. Echoing the Londoner, she acknowledged that her lighter complexion offers some protection in Europe. She further asserted that “men of color [experience discrimination in Europe] more than women of color. Still, the relationship between men of color and women of color can also be complicated—for example, some Black men can be extremely misogynistic and degrading toward Black women.” Additionally, in Burkina Faso, “men are… safer and less restricted in what they do and where they go. When I’m in the streets in [this] country, I know I must be aware of all my surroundings”—especially after dark, due to repeated “bad experiences with weird men at night.” She mentioned that it is socially and culturally unacceptable for women to go out alone at night in Burkina Faso and that women are expected to cover most of their skin, even in extreme heat.

A Belgian echoed some of the earlier observations made by the Central Asian participant, but in this case, the comparison was between Korean men and those from her home city of Liège. There, she said, problems typically begin after 7:00 or 8:00 P.M. She complained that shops in the city center close early, the lighting is poor and a sizable number of intoxicated people fill the streets at night. “I often feel stared at,” she remarked. She described the situation as “kind of intimidating. As a woman, that can be really heavy.” Although “there are drunk people [in Busan] too, … it’s different. They don’t act weird or do bad things. They are just quiet and respectful,” so much so that she has “never seen public violence or people being aggressive in the streets.” In Busan, she even observed “little kids walking alone—something that would be really dangerous in Liège.”

Many respondents attributed an increased sense of safety to CCTV cameras, ubiquitous in Korean cities and often made highly visible through large indicators projected onto sidewalks or streets. These cameras are sometimes accompanied by emergency buttons (see

Figure 9), which can be used not only in cases of assault but also for medical or other urgent situations. The extent to which CCTV and emergency systems alleviate women’s anxieties and enhance perceived safety appears to depend, at least in part, on cultural background. Korean participants consistently found CCTV reassuring, for cultural reasons that will be explored later. Central Asian women were even more emphatic in their appreciation, explicitly linking it to the lack of safety in their home countries and the comparatively safer environment in Korean cities

The earlier-mentioned Burkinabé-French woman had a mixed experience of Korean cities, but suggested CCTV cameras might add to safety. In her own words:

I’ve surprisingly felt safe going out at night no matter how I was dressed, which isn’t the case at all in France. It’s hard to explain factually why. I think it has to do with the presence of CCTV [in Korean cities], or because I feel like safety in general is more assured in this society for some reason (just as you can leave your phone somewhere and find it back in its place later, which is unimaginable in most countries). People don’t interact much in streets and tend to not pay much attention to you apart from looking.

She added, however, that “wearing crop tops or light clothes” garners “many bad looks… both from elders and young people” in Korea, with the issue more pronounced in Busan than in Seoul, where residents are more accustomed to seeing tourists. She continued: “I’m still aware that Korea is a country with many gender issues… So even though I feel safer in the streets, bars and clubs remain places where I am extra cautious, just as I would anywhere around the world.”

However, some Western participants expressed privacy concerns about CCTV monitoring. While acknowledging that urban spaces in Korea are generally very safe, one American participant noted that in the US, the presence of CCTV cameras can imply that a setting is dangerous enough to require surveillance, thereby creating a slightly menacing atmosphere. A Latin American respondent similarly viewed CCTV as ineffective. Nevertheless, she found reassurance in Busan’s numerous 24/7 convenience stores, which are often designed so that cashiers have a clear view of the street and include designated “safe zones” that can be used if problems arise or while waiting for taxis or to meet an acquaintance. Another Latin American participant emphasized that public urban spaces in Korea are almost always considerably safer than those in her home country. One critique she offered about Busan was that men on sidewalks tend to make way more often for other men than for women—though she added that this dynamic is common in many parts of the world.

Additionally, whether or not CCTV cameras contributed to a sense of safety occasionally depended on the specific locale. For example, some participants reported feeling uneasy near male dormitories at Pusan National University, Busan’s largest university. One such dormitory is situated at the edge of campus, atop a hill bordering a forested mountain area. A respondent described the location as a “place of intimidation”—not due to any specific incident, but because of its isolation. Although manned security posts with camera feeds are present, participants expressed skepticism about whether they would receive timely assistance if something were to occur.

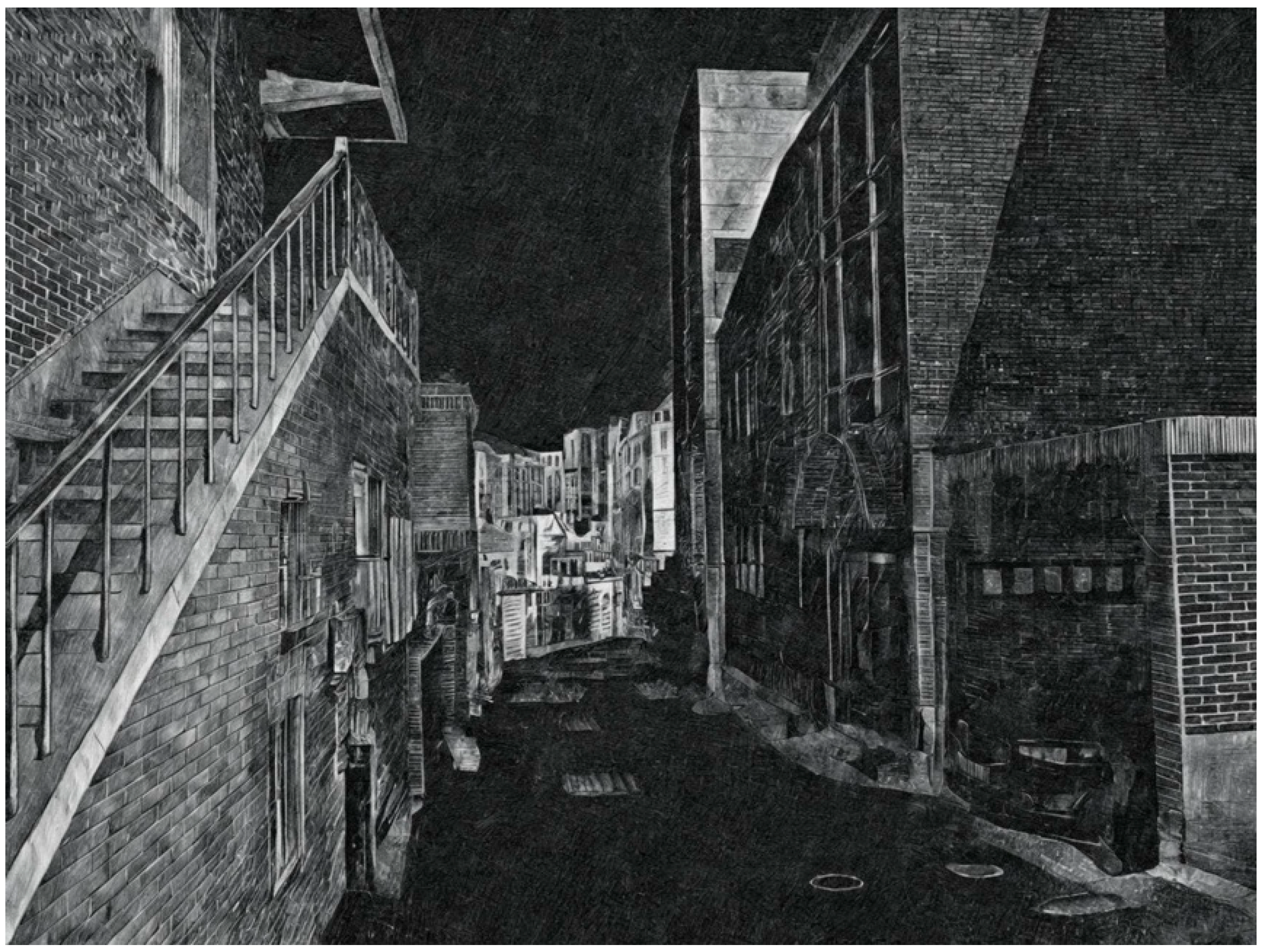

Other urban areas that women—particularly non-Koreans—found somewhat intimidating included neighborhoods with smaller buildings situated along irregular, narrow and hilly streets that do not follow a grid pattern (

Figure 10). Such areas are almost inevitable in Korean cities due to the country’s mountainous terrain and dense population. While respondents generally viewed these neighborhoods as relatively low risk, they cited several concerns: minimal lighting, restricted sight lines, limited CCTV coverage, infrequent police patrols and low levels of pedestrian or vehicle traffic. On the other hand, many foreign participants were struck by the overall cleanliness and lack of litter in Korean cities, noting that this contributed to a sense of safety, an observation that will be further explored in the discussion section.

Some Westerners reported concerns in their home regions about locations such as parking lots, gas stations and empty parks, especially at night. The underlying concern was clear: lightly populated areas reduce the likelihood of bystander intervention, increasing the perceived risk of harm—a point emphasized by several classic commentators on urban life [

64,

70]. Some Korean participants expressed a preference for open and well-organized areas with clear sightlines, such as parks. Even at night, when populations are sparse, they felt safer in such spaces than in highly trafficked areas like restaurant or bar districts. This may reflect a desire for respite in a high-density country where public crimes are relatively rare and sometimes occur more frequently in crowded settings [

71] or else in private or semi-private venues, according to respondents. Koreans also reported feeling safer in neighborhoods where families are present, which aligns with the intuitive assumption that parents are unlikely to bring children to unsafe areas.

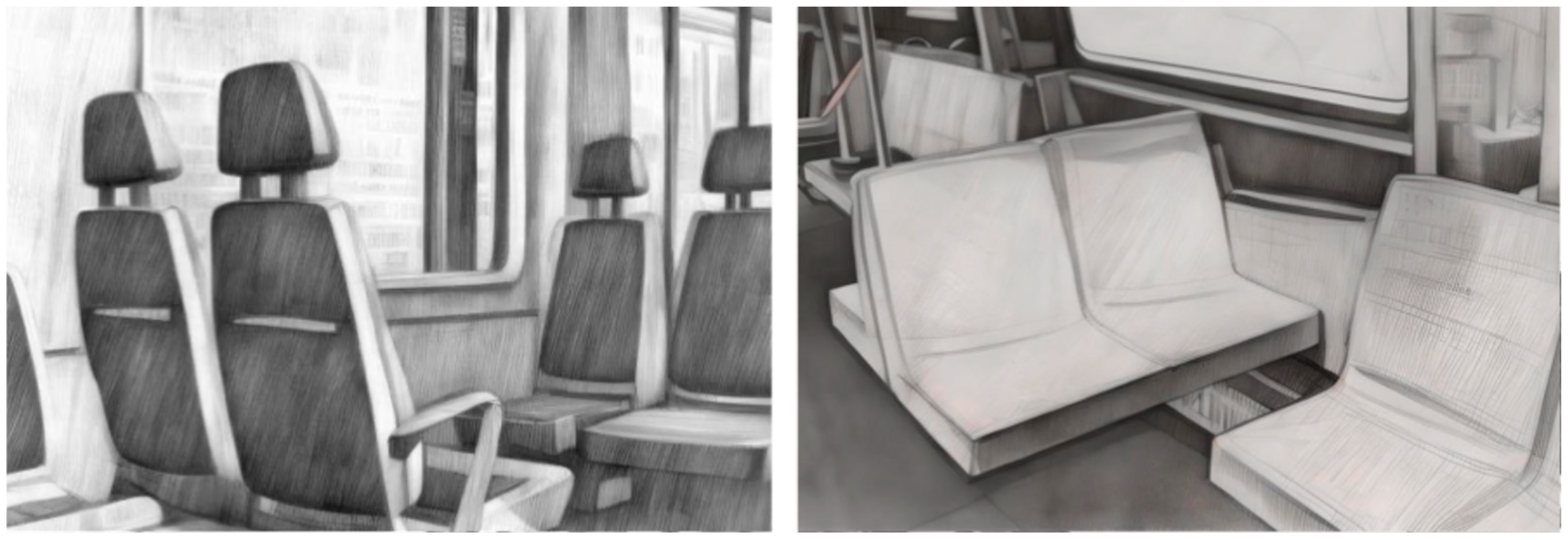

Additional remarks were centered on public transportation. A North African participant observed that the risk of verbal harassment and sexual touching on microbuses in cities like Cairo increases as the number of women riders declines. This, in turn, discourages women from using the service, further amplifying the risk through a self-reinforcing cycle. Western participants highlighted different concerns, focusing on design features of subways and commuter trains that make them socially uncomfortable and, at times, objectively unsafe. They especially flagged L-shaped seating and tight face-to-face seating (see

Figure 11). During peak hours, these configurations often lead to unwanted physical and eye contact. Discomfort intensifies when, for instance, a man’s leg becomes entangled with that of a nearby woman. Because it is often difficult to determine whether such contact is intentional or accidental, some women reported ignoring what they suspected was sexually motivated behavior. Not that women should need to vacate their seats—but doing so is often physically difficult during peak hours, and standing in a crowded train may be no safer.

Taken collectively, this sampling of responses reinforces a broadly accepted point: women’s impressions of a city locale often differ markedly from those of men. A second conclusion—consistent with the data and further developed in the next section—aligns with insights from affordance theory, the concept of selective permeability and feminist geographies, namely, that an urban setting can be objectively different for women and men.

5. Discussion

The data make it clear that experiences of politically and negatively valenced obstacles vary with gender, along with other factors like ethnicity and socioeconomic background. Now, taken strictly as a measure of perceived risk, the results are difficult to dispute—after all, as the saying goes, people feel what they feel. Yet it would be unduly dismissive to treat women’s judgments as merely subjective, even without assuming that every reaction accurately reflects actual dangers. Beyond this, the respondents’ assessments closely align with the established literature on gender disparities in urban environments [

44,

53,

55,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. The data also lend multiple lines of support to the article’s account of selective permeability.

First, in discussing instances of unwanted sexual attention—which this article has designated as politically charged negative affordances—foreigners often viewed their home regions as more problematic than Korean cities like Busan. One woman added that Koreans engage in less street harassment than foreigners, a claim echoed in a news article [

78]. As previously noted, however, this speaks more to how such offenses are perpetrated than to their overall frequency. Indeed, workplace harassment is alarmingly common in Korea [

79,

80,

81,

82]. So too are digital sex crimes, ranging from restroom spy cams and pornographic deepfakes of acquaintances to illicit photos of women, including sisters and mothers, circulated on platforms like Telegram [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87]. Taken together, these observations suggest that Korean women confront a range of negative affordances that temporary foreign visitors often evade. Instances of the reverse can occur as well, as will shortly be seen.

Second, the data suggest that factors such as gender, skin color, socioeconomic status and visible markers of religion shape the selective presence or absence of politically charged negative affordances. The surrounding culture also plays a role, as with the respondent who said she was perceived as Black in Europe and white in Africa, with corresponding social disadvantages and advantages. Another example is that several experienced more street harassment in their home countries than in Korea. Recent research combining prior studies with new data provides some explanation, which follows from the observation that Korean socialization fosters a more publicly oriented sense of self than is typical in the West [

24]. For instance, students may be assigned front or rear seats—or higher or lower shoeboxes at school—based on academic performance. More broadly, the region’s dense populations may have historically made it hard to escape others’ gaze, reinforcing a sense of being under constant observation, which persists in contemporary society. As a result, many Koreans are likely to believe that successes and failures are publicly visible and are, thus, more strongly motivated to protect their reputations [

24]. These dynamics help explain why respondents reported both lower rates of street harassment and a broader sense of public trust in Korea, such as the ability to leave a phone unattended in a café.

Third, as previously noted, sex crimes are not rare in Korea. However, such misconduct often occurs out of public view or in ambiguous forms, as in the earlier-mentioned incidents in a nightclub and shoe store, plus the digital and workplace offenses that have been discussed. For reasons just stated, Koreans are generally highly averse to being perceived as violating social norms [

88]. A 2025 incident in several Korean cities is illustrative in this regard. News outlets reported that groups of university-aged men staged a malicious TikTok prank in which they filmed themselves chasing women students under the pretense of “helping them get home safely” [

89,

90]. What stands out is that the perpetrators believed their actions were socially acceptable enough to post the videos on university student websites. Moreover, many of the subsequent apologies expressed regret not for distressing the women, but for offending community sensibilities or breaching social decorum, e.g., [

91]. Relatedly, the legal system can at times orient towards protecting public reputations at the expense of victims—a point that will be elaborated on shortly. Taken together, these social dynamics contribute to negative affordances that restrict women’s mobility and compromise their safety.

Fourth, many Koreans—like people in various other regions—hold strong antifeminist views. This stems partly from misunderstandings of feminist philosophy and its distorted portrayals on social media, as well as from the belief that gender inequality has already been resolved and that men are now the primary victims [

92,

93,

94]. The stigma against feminism is so strong that many progressive Korean women distance themselves from the movement [

15]. The antifeminist climate appears to influence men’s attitudes toward infrastructure designed to reduce the negative affordances that women face. Consider Busan’s Line 1 subway, which has women-only cars during peak hours to help prevent unwanted sexual attention, among other reasons. Some men, however, ignore these designations and complain that they are discriminatory [

15,

95]. Moreover, women-only cars are often severely overcrowded, with passengers forced to stand even when seats are available in mixed-gender sections. This suggests that some women find mixed-gender cars unwelcoming enough to willingly endure the overcrowding of women-only spaces, undermining men’s claims of unfairness.

Fifth, some participants described certain urban settings as having what were earlier termed hostile atmospheres—in their own words, “places of intimidation” that felt “really heavy.” From the enactive perspective outlined earlier, such atmospheres emerge partly from women’s embodied vulnerability, itself often a consequence of men’s actions—actions that, in turn, help constitute the atmosphere. While emotional atmospheres are observer-dependent and not typically tied to a single object or event, this does not make them merely subjective, for many other properties are similar. For instance, an object’s length depends on its velocity relative to the observer. Color perception also relies on context—people often misjudge hues when viewing a color patch in isolation. The interpretation of facial expressions likewise depends on context; for example, joyful tears may be mistaken for sadness when a face is shown in isolation [

59,

96]. Affordances are another relational property that varies depending on observers and their capacities. As noted earlier, hostile atmospheres in architectural settings have been associated with action-constraining negative affordances [

31,

57,

58,

59]. The participants’ accounts of urban spaces are consistent with this understanding.

Sixth, some foreign women noted that the absence of trash made Korean urban spaces feel more comfortable than those in their home countries. Research has long linked cleanliness to perceptions of public safety, though the reasons remain debated. One view holds that affluent areas are both cleaner and more heavily policed; another suggests that tidy environments foster social cohesion and shared responsibility, encouraging locals to intervene when they witness wrongdoing [

97,

98]. Cleanliness also shapes a neighborhood’s emotional atmosphere. Studies show that litter increases anxiety about incivility and crime. These effects are similar across genders, though women tend to have higher baseline concerns about crime [

99]. If cleanliness attracts people, there should be more eyes on the street. If it specifically invites families with children, their presence may help enact safety further, given that one London borough found that painted images of babies reduce crime [

13].

Seventh, the flip side is that unkept urban spaces not only appear uninviting but have also been shown to trigger negative moods [

100]. As previously noted, this can make environments unwelcoming, not to mention less accessible because despondency lowers energy, so that destinations are harder to reach. Families will typically avoid unpleasant, high-risk or low-accessibility areas, but their absence may, in turn, erode safety—again extrapolating from the London findings. One study interestingly adds that greenery reduces petty crime and littering in Korea [

101]. However, cleanliness may instead be a byproduct of the same civic-mindedness that discourages Korean men from street harassment or makes it so that people can leave valuables on a café table and step away for lunch without much fear of theft. At the same time, some research suggests that litter increases women’s perception of crime risk more than men’s [

102]. If so, we might expect women to frequent a place less, which can increase dangers for those who do use the area, for reasons explained earlier. Whatever the case, the data from this article and other research point once more to the selective presence of negative affordances, whether in specific parts of a venue or from strewn garbage and other environmental features shaping the overall atmosphere.

Eighth, classic urban theorists have emphasized the importance of “eyes on the street”, particularly those belonging to individuals who feel a sense of civic-minded ownership over a space [

64,

70]. The data from this study does not challenge that view. However, it suggests that people’s sensitivity to the absence of others often corresponds with the actual level of danger in each area. In safer cities or neighborhoods, residents may feel relatively indifferent to the presence of others and may even prefer less foot traffic. Several Korean respondents, for instance, expressed a preference for quieter areas, and it is common in cities like Busan to see women of all ages sitting or walking in relatively empty public spaces, even alone at night (see

Figure 12). The chosen locations may be well lit and offer clear sightlines. But they may also be devoid of businesses that help ensure a steady stream of pedestrians, which scholars like Jane Jacobs deem vital to protecting public safety [

64]. A lesson here is that design principles that are effective in one context may not apply universally. This aligns with the selective permeability model, which recognizes that broad generalizations often fail to hold. Indeed, several cases discussed in the results section suggest that roughly the same physical design can exhibit high or low penetrability (e.g., varying degrees of hostility and accessibility) depending on the context in which it is implemented. The degree of penetrability—or non-hostility—may depend on broad contextual factors, such as the national character of a region, or on more localized social conditions, including the cultural identity and intoxication level of the men occupying a given district.

Although Korea’s urban settings have mostly been portrayed favorably, none of this downplays the negative affordances that its cities and culture impose on women, often unequally. For example, interviewees mentioned knowing a foreigner who was justifiably prosecuted for harassing a Korean woman. However, when the respondent who was intimately touched in the shoe store went to file a complaint, she was dissuaded by a female officer’s repeated warnings that the accused man could file charges against her. It turns out the warning is not empty. A UK government webpage cautions that the accused, if found not guilty, can file “a claim of false accusation” against the complainant [

103]. While not unreasonable in cases of defamation, the warning is strange given the rarity of fictitious allegations [

104,

105]. An added problem is that Korean law defines sexual assault primarily in terms of physical force, with lack of consent not a main consideration. Past charges have been dismissed because judges held that survivors had “not resisted hard enough” [

106].

The other interviewee, who was forcibly kissed, had an experience with law enforcement that closely paralleled that of the woman who experienced uninvited intimate touching. Because she was being followed in the street by the assailant who had assaulted her in the nightclub, she went into a police station for protection and to file a complaint, only to be told there was nothing to be done because she was a foreigner. While the claim is implausible, the problem is common enough that an advisory from the Canadian government warns that Korean police “may not always respond adequately to reports of sexual violence and harassment” [

107].

While an extended sociology of Korea is beyond the scope of this article, some scholars have noted that older generations of Koreans tend to avoid interfering with outsiders. This behavior has been linked to a historical context in which communities were collectively rewarded or punished, encouraging people to police their own group while ignoring others [

108] (pp. 31–32). Additionally, within living memory, Korea consisted of relatively isolated villages [

109,

110]. These were separated by mountains, with even short distances difficult to traverse due to a lack of tunnels, and in-group bias may be a partial artifact of this history and geography [

24]. Whatever the causes, it appears that individuals from different parts of the world can face distinct negative affordances in Korean cities due to the selective ways in which locals assert a sense of proprietorship over both city spaces and those who occupy them.

6. Conclusions

This article began by outlining the theoretical foundations of the selective permeability model, emphasizing the political character of urban affordances and the ways in which built form filters individuals based on demographic factors, especially gender. It then presented supporting empirical data. Throughout, the argument was made that selective permeability aligns well with Gibson’s theory of affordances and warrants a shared conceptual vocabulary, even while important divergences were acknowledged.

As for the data, it has been stated that findings are illustrative rather than definitive. The aim was in part to identify future research directions and to lay the groundwork for possible quantitative measures. Still, it is worth reiterating that nearly all data dealing with cultural phenomena are better seen as illustrative than systematically conclusive. One reason is that participants are typically self-selecting, which introduces bias. As noted earlier, data parsing can be arbitrary. Cultural psychologists, for instance, have sometimes categorized subjects by nationality and at other times by ethnic identity—approaches that can obscure meaningful distinctions. Results may also shift when subcategories such as socioeconomic status, religion, political affiliation, health or urban–rural background are included, each of which may predict different outcomes depending on the specific region or country.

Another stated challenge is that cultures evolve. One example is how the World Wide Web is altering East Asian societies; another is that increased material wealth and declining birthrates have also contributed to changing domestic conditions, such as children growing up with their own bedrooms, producing greater expectations of privacy [

111].

Issues like those just stated make it difficult to draw lasting generalizations. Yet that is precisely the advantage of the selective permeability model: it presupposes the existence of shifting variations. The data presented in this article, for instance, suggest that the same setting may pose different risks to two women, depending on their ethnicity or socioeconomic background and also depending on the specific culture encountered, which can privilege or disadvantage the same individual as she moves between regions.

Leanne Rivlin, drawing on Gibson, expresses the truism that “affordances enable the discovery of possibilities, an important dimension of public space that helps to satisfy people’s needs” [

67] (p. 40). She highlights that freedom of choice is central to public life, allowing individuals to define and make use of spaces in ways that reflect their values. This may take positive forms—as when a street performer or fruit vendor becomes a focal point that shapes a place’s identity—but it can also occur in selectively negative ways. One reason is that making a space safer or more usable for some may come at the expense of others. A straightforward example involves public transit seating. Some riders may appreciate the sociability of face-to-face or L-shaped seating and benefit from its inclusion. But these arrangements can also heighten risk for women during peak hours, especially in systems where avoiding such seating may force them to stand, which can also increase the chances of unwanted physical contact.

Another point emerging from the data is that normative values are often embedded in the built environment. Design choices—whether intentional or not—can amplify negative affordances for certain segments of the population. This ties into the concept of political affordances, highlighting how boundaries that are often implicit and invisible to most people nonetheless guide human movement along demographic lines. Not all of this is unjustifiable, as when a picket fence marks a play area next to a dwelling as private. But in other cases, such as transit layouts that compromise women’s safety or restroom stalls shaped around male biomechanics, the built environment reflects, reproduces and materially instantiates regressive normative assumptions about women and their role in public space.