The Impact of Contextual Constraints on the Role of Management Commitment in Safety Culture: A Moderation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Safety Culture: Concept and Core Components

2.2. Management Commitment as an Expression of Organizational Support for Safety

2.2.1. Management Commitment and the Implementation of SMS

2.2.2. Management Commitment and Worker Participation

2.3. Critical Contextual Factors: Barriers to PPE Use and Physical Job Demands

2.3.1. Perceived Barriers to PPE Use

2.3.2. Physical Job Demands

2.3.3. Justification for Their Analysis as Moderating Variables

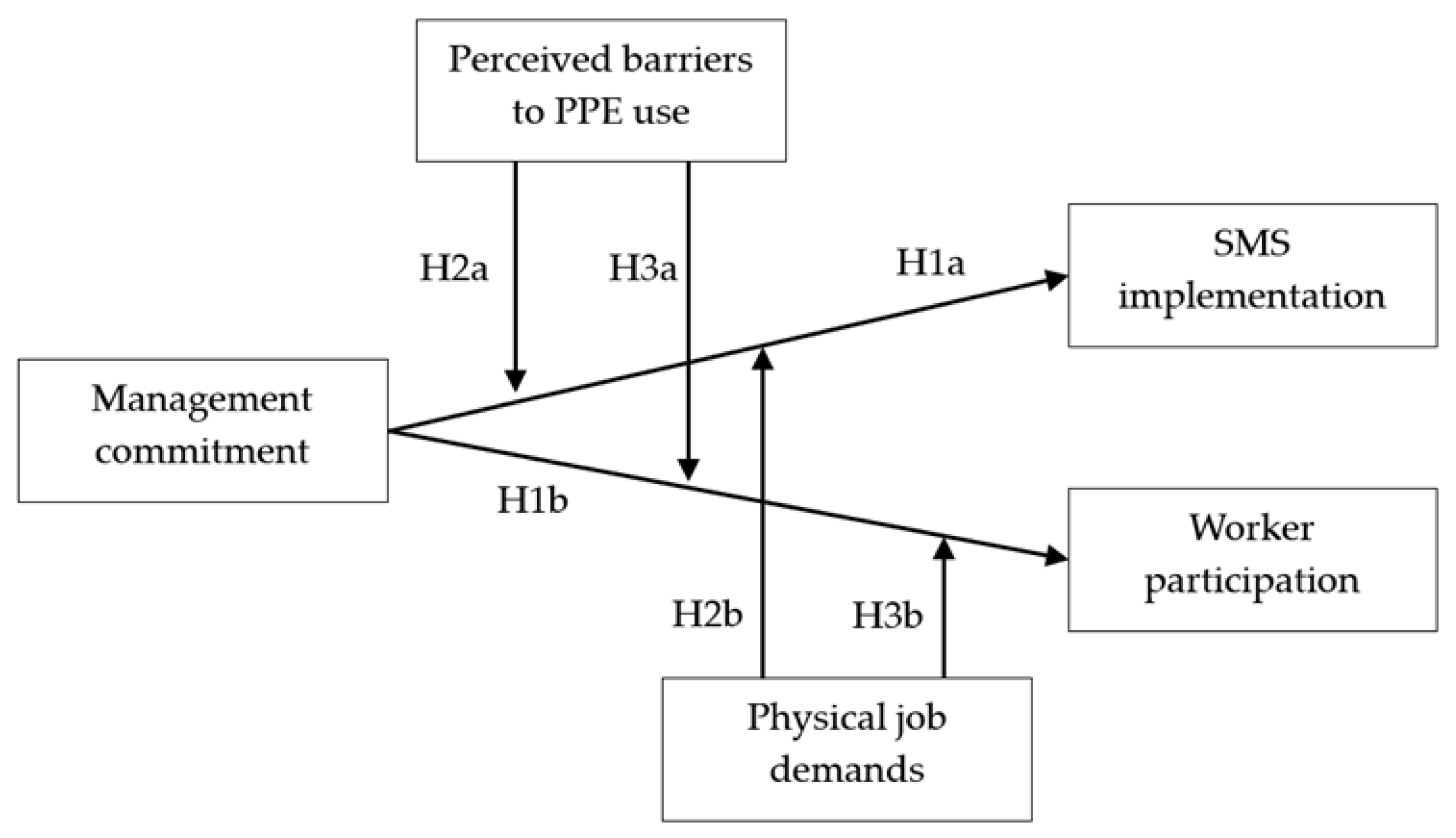

2.4. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

2.4.1. Specific Objective 1

2.4.2. Specific Objective 2

2.4.3. Specific Objective 3

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Procedures

3.4. Data Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

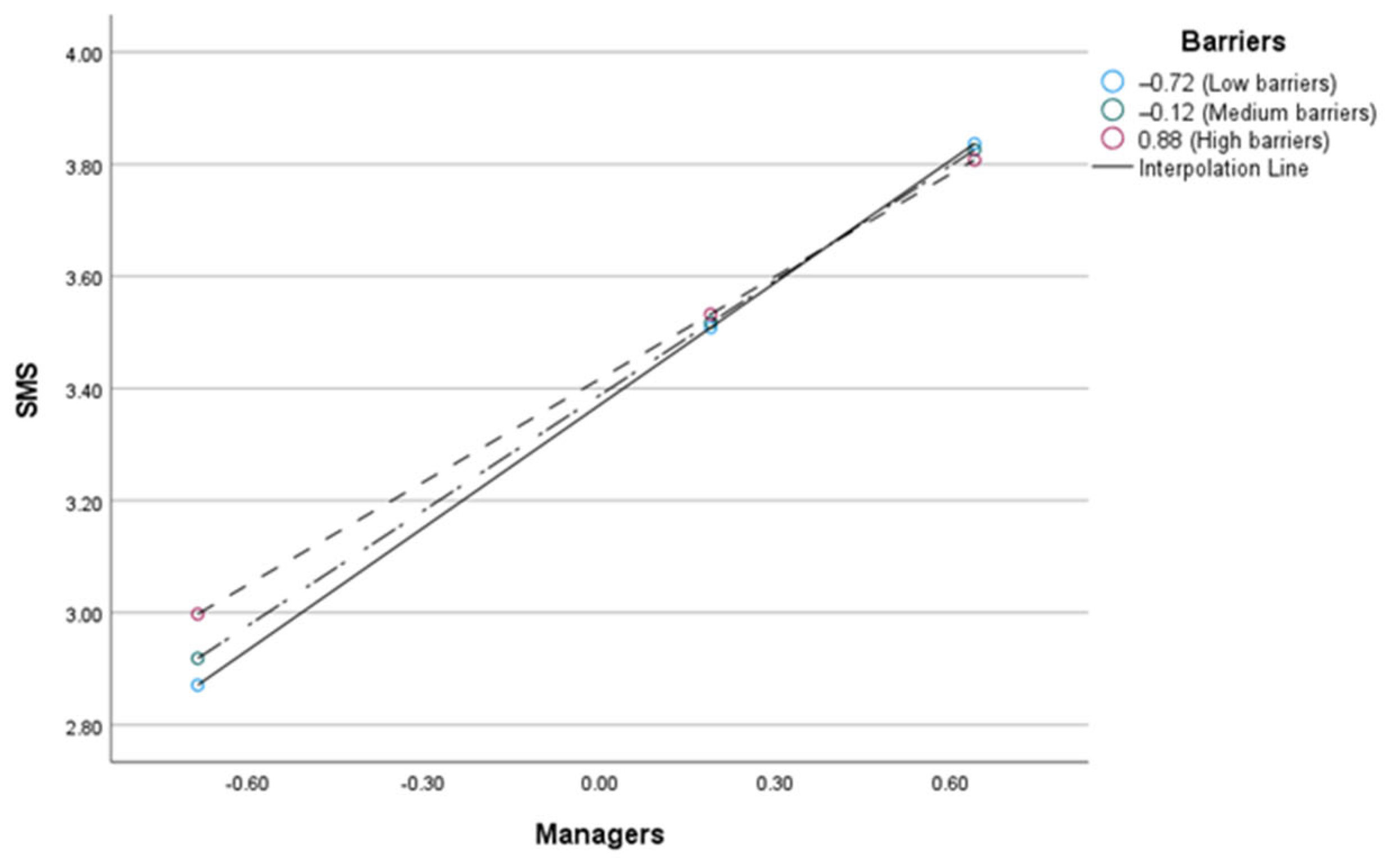

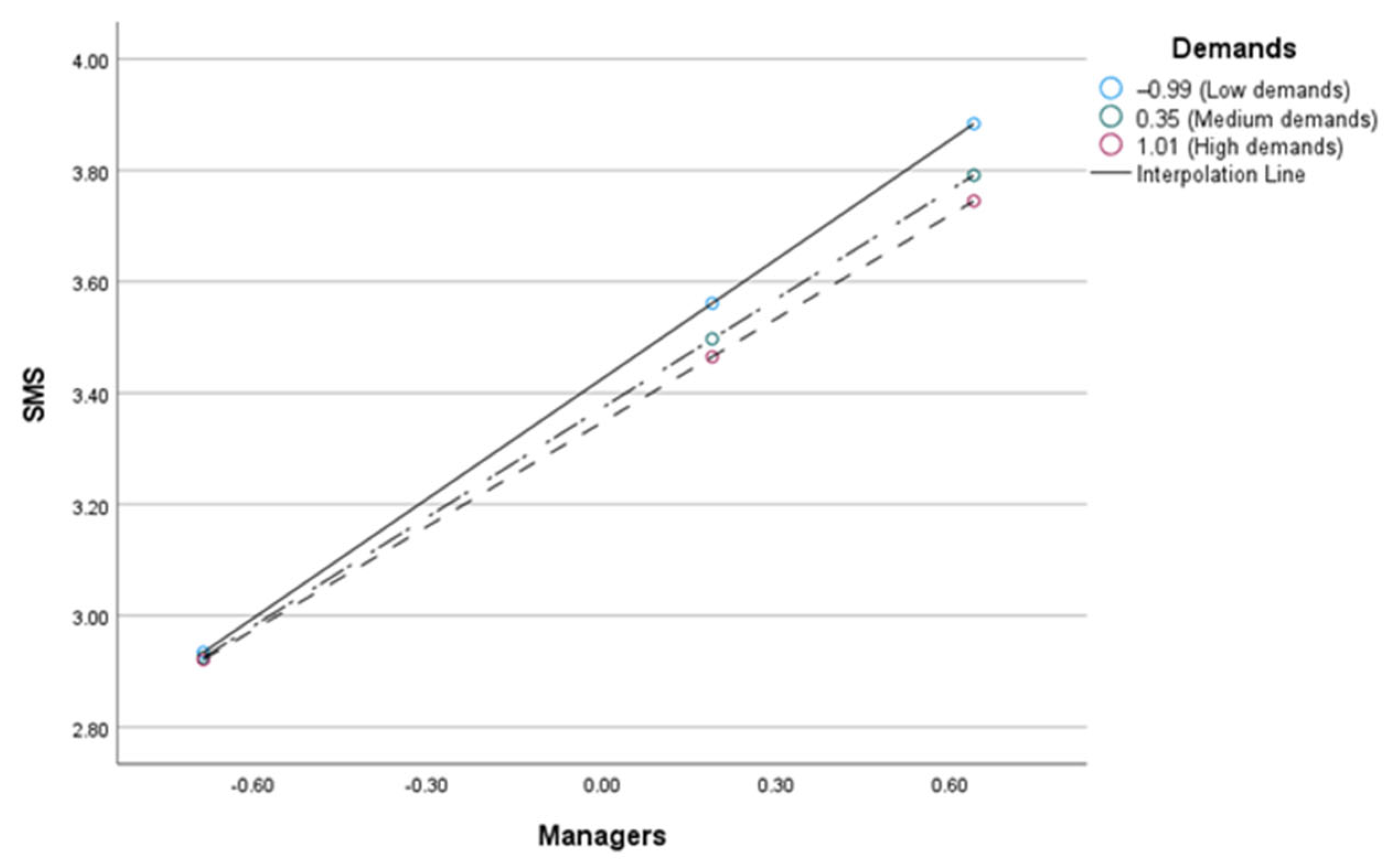

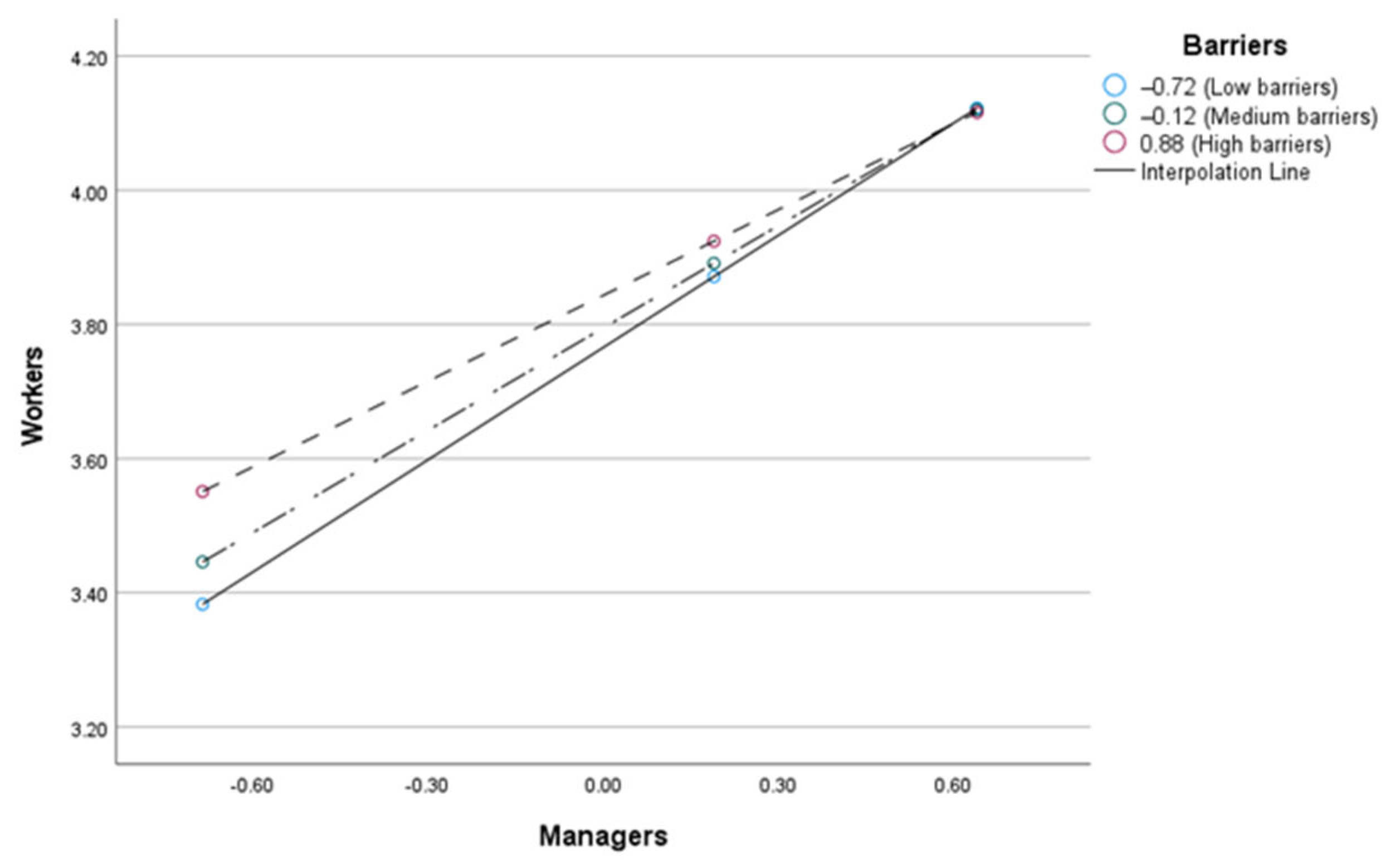

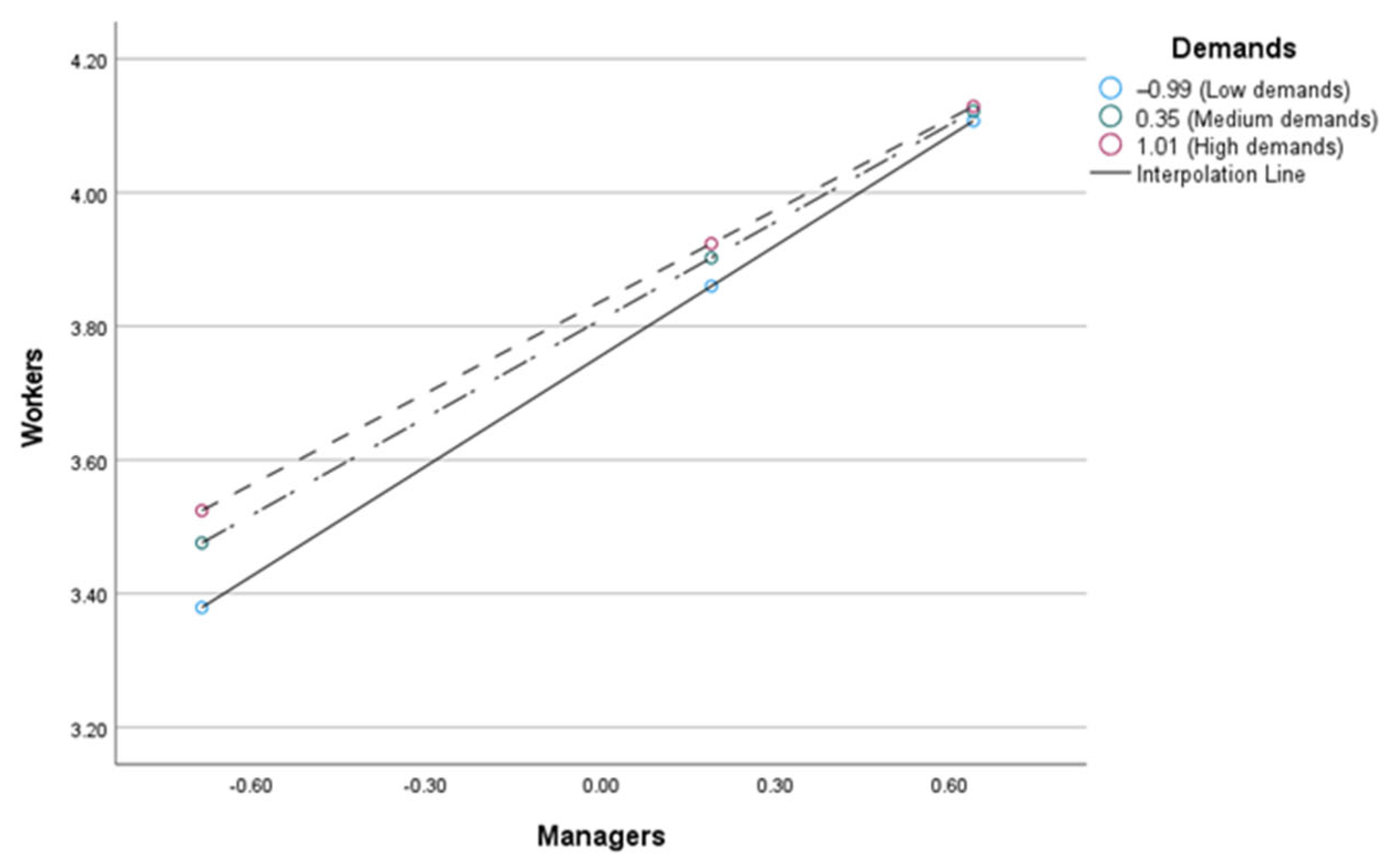

4.2. Moderation Analyses

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SC | Safety culture |

| SMS | Safety management systems |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| SDG | Sustainable development goal |

| OHS | Occupational health and safety |

References

- da Silva, S.C.A.; André, E.G.D.T.F.P.; Serranheira, F.M.S.; de Sousa, J.D.M.; Dias, J.M.B.; Nogueira, J.M.R.; Cunha, L.M.S.; Freitas, L.C.; Arrabaço, M.F.S.R.; Prata, N.; et al. Green Paper on the Future of Occupational Safety and Health; Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento do Ministério do Trabalho, Solidariedade e Segurança Social: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022.

- International Labour Organization [ILO]. Safety and Health at the Heart of the Future of Work: Leveraging 100 Years of Experience; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Milošević, I.; Stojanović, A.; Nikolić, Đ.; Mihajlović, I.; Brkić, A.; Perišić, M.; Spasojević-Brkić, V. Occupational health and safety performance in a changing mining environment: Identification of critical factors. Saf. Sci. 2025, 184, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Accidents at Work Claimed 3 286 Lives in 2022 in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20241119-1 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- International Labour Organization [ILO]. Enhancing Social Dialogue Towards a Culture of Safety and Health: What Have We Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis? International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Priolo, G.; Vignoli, M.; Nielsen, K. Risk perception and safety behaviors in high-risk workers: A systematic literature review. Saf. Sci. 2025, 186, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autoridade para as Condições do Trabalho [ACT]. Serious Work Accidents. Available online: https://portal.act.gov.pt/Pages/acidentes_de_trabalho_graves.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Autoridade para as Condições do Trabalho [ACT]. Fatal Work Accidents. Available online: https://portal.act.gov.pt/Pages/acidentes_de_trabalho_mortais.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Esquerda.net. Fatal Work Accidents Have Increased in the Last Five Years. Available online: https://www.esquerda.net/artigo/acidentes-de-trabalho-fatais-aumentaram-nos-ultimos-cinco-anos/93850 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Eurostat. Accidents at Work—Statistics on Causes and Circumstances. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_at_work_-_statistics_on_causes_and_circumstances (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Eurostat. Accidents at Work Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_at_work_statistics (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Ahmad, T.L.; Fitria, H.; Hakim, C.B. The influence of work safety culture and work safety monitoring system on work safety. J. Ind. Eng. Halal Ind. 2022, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Son, K.; Park, C.; Kim, D. Suggestions for improving South Korea’s fall accidents prevention technology in the construction industry: Focused on analyzing laws and programs of the United States. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.; Silva, I.S. Indicators to assess safety performance: A literature review on safety culture in industry and construction sectors. Int. J. Work. Cond. 2024, 27, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Rhee, S.Y.; Yoon, Y.G. Enhancing worker safety behaviors through the job demands–resources approach: Insights from the Korean construction sector. Buildings 2025, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P.; Hancock, P.; Leveson, N.; Noy, I.; Sznelwar, L.; Van Hootegem, G. Advancing a sociotechnical systems approach to workplace safety–developing the conceptual framework. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Safety culture: Analysis of the causal relationships between its key dimensions. J. Saf. Res. 2007, 38, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.; Silva, I.S. Dimensions of occupational safety culture and safety performance: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Work. Cond. 2023, 25, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. Towards a model of safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2000, 36, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; Mohyaldinn, M.E.; Leka, S.; Saleem, M.S.; Rahman, S.M.N.B.S.A.; Alzoraiki, M. Impact of safety culture on safety performance; mediating role of psychosocial hazard: An integrated modelling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, V. Developing and Testing a Safety Culture Model: The Workers’ Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tappura, S.; Jääskeläinen, A.; Pirhonen, J. Creation of satisfactory safety culture by developing its key dimensions. Saf. Sci. 2022, 154, 105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunodzia, R.; Bikitsha, L.S.; Haldenwang, R. Perceived factors affecting the implementation of occupational health and safety management systems in the South African construction industry. Safety 2024, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leso, V.; Carugno, M.; Carrer, P.; Fusco, F.; Mendola, M.; Coppola, M.; Zaffina, S.; Di Prinzio, R.R.; Iavicoli, I. The total worker health® (TWH) approach: A systematic review of its application in different occupational settings. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NP ISO 45001; Portuguese Standard: Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements and Guidance for Use. Instituto Português de Qualidade: Almada, Portugal, 2019.

- Ye, X.; Ren, S.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. The mediating role of psychological capital between perceived management commitment and safety behavior. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 72, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J. Human and workplace factors contributing to PPE non-compliance: A critical assessment. In Construction Research Congress 2024: Health and Safety, Workforce, and Education; Shane, J.S., Madson, K.M., Mo, Y.L., Poleacovschi, C., Sturgill, R.E., Jr., Eds.; Construction Research Council: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2024; pp. 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, M.; Temel, B.A.; Basaga, H.B. A study on the use of personal protective equipment among construction workers in Türkiye. Buildings 2024, 14, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.T.; Feng, Y. A maturity model for resilient safety culture development in construction companies. Buildings 2022, 12, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]; Burton, J. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Core elements of safety culture and safety performance: Literature review and exploratory results. Int. J. Soc. Syst. Sci. 2009, 1, 227–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. The role of safety leadership and working conditions in safety performance in process industries. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2017, 50, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisbey, T.M.; Kilcullen, M.P.; Thomas, E.J.; Ottosen, M.J.; Tsao, K.J.; Salas, E. Safety culture: An integration of existing models and a framework for understanding its development. Hum. Factors 2021, 63, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansong, A.; Amadu, S.S.; Yeboah, M.A. Ethical leadership, safety climate, and employee health and safety: Lessons from the oil and gas industry in Ghana. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2023, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.R.; Lucianetti, L.; Pindek, S.; Spector, P.E. “Walking the talk”: The role of frontline supervisors in preventing workplace accidents. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, L.S.; Lipscomb, H.; Cifuentes, M.; Punnett, L. Associations between safety climate and safety management practices in the construction industry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Skibniewski, M.J. Perceiving interactions on construction safety behaviors: Workers’ perspective. J. Manag. Eng. ASCE 2016, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.K.; Rahim, N.F.A.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B. The role of the safety climate in the successful implementation of safety management systems. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, S.; Paton, K.; Hayes, C.; Morrison, B. A day in the life of frontline manufacturing personnel: A diary-based safety study. Saf. Sci. 2020, 132, 104992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Goldenhar, L.M.; Byrd, J.L.; Betit, E. The safety climate assessment tool (S CAT): A rubric-based approach to measuring construction safety climate. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 69, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaz, J.S.; Fedajev, A.N.; Petrović, D.V.; Stojadinović, S.; Zlatanović, D.M.; Stojković, P.Z.; Stajić, M.S.; Radovanović, M.B. Towards safer mines: Analyzing occupational health and safety perceptions and injury patterns in Serbian underground mining. Work 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Elghaish, F.; Zamil, A.M.A.; Alhusban, M.; Qaralleh, T.J.O. Benefits of implementing occupational health and safety management systems for the sustainable construction industry: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1980, 65, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Pei, J. The mediating role of safety management practices in process safety culture in the Chinese oil industry. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2019, 57, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, F.; Modjo, R.; Wibowo, A.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Influence of safety climate on safety performance in gas stations in Indonesia. Safety 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, A.; Adam, A.; Claudia Gala, C. Behavior analysis of the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for workers at PT. Maruki International Indonesia. Soc. Work Public Health 2024, 39, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, R.; Hallowell, M.; Balaji, R.; Bhandari, S. Safety risk tolerance in the construction industry: Cross-cultural analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. ASCE 2020, 146, 04020022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, H. Modified accident causation model for highway construction accidents (ACM-HC). Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 28, 2592–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.; Man, S.S.; Chan, A.H. Critical factors for the use or non-use of personal protective equipment amongst construction workers. Saf. Sci. 2020, 126, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaira, M.M.; Hadikusumo, B.H.W. Structural equation model of integrated safety intervention practices affecting the safety behaviour of workers in the construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2017, 98, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Kazemi, S.E.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M. The last mile: Safety management implementation in construction sites. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J.; Rener, A.T.; Listello, M.P.; Mohamed, M. PPE non-compliance among construction workers: An assessment of contributing factors utilizing fuzzy theory. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, A. Common Issues of Compliance with Personal Protective Equipment for Construction Workers. Bachelor’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, March 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cmsp/436 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Boukas, D.; Kontogiannis, T. A system dynamics approach in modeling organizational tradeoffs in safety management. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2019, 29, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalteh, H.O.; Salesi, M.; Cousins, R.; Mokarami, H. Assessing safety culture in a gas refinery complex: Development of a tool using a sociotechnical work systems and macroergonomics approach. Saf. Sci. 2020, 132, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Lee, S.J.; Bao, S.; de Castro, A.B.; Herting, J.R.; Johnson, K. Interaction between physical demands and job strain on musculoskeletal symptoms and work performance. Ergonomics 2023, 66, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasota, A.M. A new approach to ergonomic physical risk evaluation in multi-purpose workplaces. Tehnički Vjesnik 2020, 27, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Keegel, T.; Louie, A.M.; Ostry, A.; Landsbergis, P.A. A systematic review of the job-stress intervention evaluation literature, 1990–2005. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2007, 13, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action—For Employers, Workers, Policymakers and Practitioners; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J.; Keegel, T.; Smith, P.M. Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Safety leadership, risk management and safety performance in Spanish firm. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.; Adhikari, A.; Yin, J.; Vogel, R.; Smallwood, S.; Shah, G. Issue of compliance with use of personal protective equipment among wastewater workers across the southeast region of the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, A.; Silva, I.; Moreira, T. Test of a safety culture model from a management perspective. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2020, 22, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.C.R.; Jordão, F.; Costa, P. The mediator role of the perceived working conditions and safety leadership on the relationship between safety culture and safety performance: A case study in a Portuguese construction company. Anal. Psicol. 2022, 1, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, T. Questionário de Desenho do Trabalho-Portuguese Translation of Work Design Questionnaire from Frederick P. Morgeson & Stephen E. Humphrey (2006); University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2015; Available online: https://www.morgeson.com/downloads/Portuguese_WDQ.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, S.H. Socio-technical systems theory: An intervention strategy for organizational development. Manag. Decis. 1997, 35, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjestveit, K.; Aas, O.; Holte, K.A. Occupational injury rates among Norwegian farmers: A sociotechnical perspective. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 77, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterson, P.; Robertson, M.M.; Cooke, N.J.; Militello, L.; Roth, E.; Stanton, N.A. Defining the methodological challenges and opportunities for an effective science of sociotechnical systems and safety. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 565–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; Alazzani, A.; Saleem, M.S.; Alzoraiki, M. Assessing the mediating role of safety communication between safety culture and employees safety performance. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 840281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikdar, A.A.; Sawaqed, N.M. Ergonomics, and occupational health and safety in the oil industry: A managers’ response. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2004, 47, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J.; Lin, H.K.; Chen, G.; Yi, S.; Choi, J.; Rui, Z. Effect of occupational health and safety management system on work-related accident rate and differences of occupational health and safety management system awareness between managers in South Korea’s construction industry. Saf. Health Work 2013, 4, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SMS | 3.39 (0.60) | (0.89) | ||||

| 2. Management | 3.69 (0.74) | 0.84 *** | (0.88) | |||

| 3. Workers | 3.80 (0.55) | 0.66 *** | 0.67 *** | (0.70) | ||

| 4. Barriers | 2.72 (0.81) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | (0.84) | |

| 5. Demands | 3.65 (0.94) | −0.15 ** | −0.11 * | 0.00 | 0.20 *** | (0.92) |

| B | SE | t | p | 95% CI 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Model 1 (perceived barriers as moderator) | ||||||

| Constant | 3.39 | 0.02 | 229.69 | *** | 3.36 | 3.42 |

| Management | 0.68 | 0.02 | 33.94 | *** | 0.64 | 0.72 |

| Barriers | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.52 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| Management × Barriers | −0.07 | 0.02 | −3.33 | *** | −0.12 | −0.03 |

| Model 2 (physical job demands as moderator) | ||||||

| Constant | 3.87 | 0.02 | 228.46 | *** | 3.36 | 3.42 |

| Management | 0.67 | 0.02 | 33.48 | *** | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| Demands | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.47 | * | −0.07 | −0.01 |

| Management × Demands | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.52 | * | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| B | SE | t | p | 95% CI 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Model 3 (perceived barriers as moderator) | ||||||

| Constant | 3.80 | 0.02 | 206.18 | *** | 3.77 | 3.84 |

| Management | 0.50 | 0.03 | 20.06 | *** | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Barriers | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.05 | * | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Management × Barriers | −0.08 | 0.03 | −2.99 | ** | −0.14 | −0.03 |

| Model 4 (physical job demands as moderator) | ||||||

| Constant | 3.80 | 0.02 | 204.71 | *** | 3.76 | 3.83 |

| Management | 0.50 | 0.03 | 20.11 | *** | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Demands | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.06 | * | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Management × Demands | −0.05 | 0.02 | −1.97 | * | −0.09 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, V.S.; Silva, I.S.; Costa, D. The Impact of Contextual Constraints on the Role of Management Commitment in Safety Culture: A Moderation Analysis. Societies 2025, 15, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060145

Pinto VS, Silva IS, Costa D. The Impact of Contextual Constraints on the Role of Management Commitment in Safety Culture: A Moderation Analysis. Societies. 2025; 15(6):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060145

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Viviana S., Isabel S. Silva, and Daniela Costa. 2025. "The Impact of Contextual Constraints on the Role of Management Commitment in Safety Culture: A Moderation Analysis" Societies 15, no. 6: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060145

APA StylePinto, V. S., Silva, I. S., & Costa, D. (2025). The Impact of Contextual Constraints on the Role of Management Commitment in Safety Culture: A Moderation Analysis. Societies, 15(6), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060145