1. Introduction

The success and effectiveness of healthcare organizations, especially public institutions, depend on employee performance (EP). EP refers to the extent to which an individual fulfills job requirements by ensuring the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of their output, hence contributing to the organization’s objectives [

1]. EP at public hospitals pertains to maintaining operational efficiency, adhering to professional standards, delivering high-quality patient care, and ensuring the overall viability and sustainability of healthcare services. High-performing staff are more inclined to maximize resource use, improve patient outcomes, and increase hospital care satisfaction [

2]. This aligns with sustainable development goal (SDG) 3, which underscores the advancement of well-being and the assurance of healthy lives for all ages. Hospitals can improve care quality while attaining universal health coverage, a vital target of SDG 3.

The efficiency of public hospital employees is a pivotal element in the enduring viability of healthcare systems [

3]. To attain sustainability, it is essential to mitigate operational inefficiencies, minimize healthcare expenditures, and enhance service quality [

4]. By optimizing EP, these goals can be objectively achieved. This is especially significant with regard to SDG 12, which emphasizes responsible production and consumption while urging healthcare systems to minimize waste and optimize resource utilization. Public hospitals, by establishing systems that deliver high-quality care while judiciously employing resources and improving operational efficiency, advance the aim of sustainable development. Thus, a heightened EP is crucial for the sustainability of healthcare systems, as it ensures their efficacy and ability to deliver high-quality, long-term medical care.

Workforce diversity management (WFDM) is the systematic and strategic process employed by organizations to recognize, appreciate, and effectively utilize the diverse attributes of their personnel, including gender, age, ethnicity, and cultural background [

5]. WFDM of public hospitals means creating inclusive environments that appreciate individual differences and promote equitable opportunities, collaboration, and organizational efficacy. Promoting variety allows hospitals to utilize various ideas, skills, and methodologies, improving patient care and operational efficiency. SDG 10, which aims to reduce inequalities between and within nations, and SDG 5, which is dedicated to empowering all women and girls and achieving gender equality, align with this plan. In healthcare environments, proficient workforce diversity management ensures that all employees, regardless of their background, possess an equitable opportunity to contribute to the organization’s success [

6].

Furthermore, WFDM fosters an inclusive and respectful culture, which is vital for cultivating cohesive teams and improving overall performance. In contemporary culture, a varied workforce at public hospitals can enhance cultural competency and communication, which are crucial, while providing innovative perspectives on patient care [

7,

8]. This guarantees that healthcare services are fair, accessible, and attuned to the requirements of varied populations, thus fulfilling SDG 3. A workforce that reflects its community is more proficient at identifying and addressing the distinct health concerns of different demographic groups [

9]. Hospitals can advance the overarching goals of sustainable healthcare, such as health equity and inclusivity, by implementing efficient WFDM protocols. They can also cultivate a more welcoming and supportive workplace atmosphere.

Public hospitals in Ghana confront significant challenges in WFDM while striving to improve EP in an increasingly heterogeneous environment. Despite the recognized benefits of diversity, such as increased creativity and improved decision-making, public hospitals sometimes juggle to manage a workforce comprising individuals from diverse cultural, racial, and gender backgrounds. Despite studies such as Obeng et al. [

8], Van Knippenberg et al. [

10], Khatri [

11] and Almarayeh [

12] indicating that diversity improves performance, the underutilization of the varied talent pool frequently stems from an absence of established diversity management protocols. Insufficient diversity management may lead hospitals to overlook the potential for improving patient care, service delivery, and organizational performance.

Gender diversity (GD) poses a unique problem. Despite evidence indicating that gender diversity can improve organizational results [

13,

14], there remains insufficient knowledge of its impact on employee performance and workforce diversity management within the healthcare industry. GD is a prominent issue in many Ghanaian public hospitals, with women often underrepresented in leadership roles. Research on the impact of gender diversity on employee performance regarding diversity management practices is lacking in the healthcare sector. Further research is necessary to fill this gap, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of how GD and WFDM interact to influence EP in public hospitals and how these interactions can foster the development of inclusive and effective healthcare teams. Incorporating gender diversity into WFDM efforts could provide a more holistic strategy for improving organizational effectiveness and employee performance in public hospitals, achieving SGD 5 (Gender Equality) and 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

This study leverages the social categorization theory (SCT) to examine the influence of WFDM on EP while considering GD a moderator in this relationship within the healthcare industry in Ghana. It seeks to answer the following questions: How does WFDM influence EP? How does GD affect EP? How does GD moderate the relationship between WFDM and EP?

This study empirically examines the direct effect of WFDM on EP within the setting of public hospitals in Ghana, thereby enhancing the current body of research on the topic. Concentrating on the healthcare sector provides a distinctive viewpoint on the influence of diversity management methods on key performance indicators in a context where teamwork, communication, and cooperation are vital. This study of WFDM in a healthcare-oriented, non-Western context enhances the understanding of diversity management in public institutions. It demonstrates how inclusive practices can enhance healthcare service delivery and employee outcomes.

This study examines the specific impact of gender diversity on employee performance, EP, in public hospitals in Ghana, thereby addressing a significant gap in the literature. Recognizing gender diversity as a separate element highlights the possibility of enhanced team dynamics, cooperation, and overall efficacy in the healthcare sector through equitable gender representation. This focus on GD offers a deeper comprehension of its direct effects on employee outcomes, highlighting the importance of gender-balanced teams in critical settings like public healthcare, alongside essential diversity management strategies.

This study investigates the influence of GD on the correlation between EP and WFDM. Analyzing this moderating effect reveals how GD affects the direction or size of WFDM’s performance impact and offers a nuanced understanding of the possible effectiveness of diversity initiatives. This analysis provides critical insights for formulating equitable and effective diversity policies, demonstrating how GD within teams can amplify the positive impacts of WFDM practices on performance results, especially in the setting of public hospitals in Ghana.

This research is important from both an academic and practical standpoint. It enhances the body of information concerning the impact of diversity management on performance in academia, especially about advancing healthcare systems in countries. It focuses on Ghana’s public hospitals and offers a culturally relevant viewpoint on workforce diversity, tackling an underexplored subject and yielding insights into diversity dynamics beyond Western contexts. The findings will aid researchers in comprehending the influence of diversity, especially gender diversity, on employee performance in critical environments such as healthcare.

This study contributes to attaining the UN SDGs (3, 5, 10 and 12). Investigating the impact of WFDM and GD on EP in Ghana’s public healthcare sector emphasizes the necessity to cultivate diverse, inclusive work environments. Gender equality, enhanced work efficiency, and the rectification of disparities in the healthcare sector propel the achievement of SDGs aimed at fostering well-being, empowering women, and cultivating inclusive, equitable workplaces.

2. Theoretical Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Categorization Theory

This study, grounded on Social Categorization Theory (SCT), clarifies how individuals categorize themselves and others based on observable or perceived characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, or roles [

15]. This concept clarifies the impact of GD on team dynamics and EP within Ghana’s public healthcare system. These social attributes significantly influence both group dynamics and interpersonal interactions. According to SCT, individuals are more inclined to identify with those with similar characteristics, enhancing their sense of connection and belonging inside these “in-groups [

8]”. Conversely, individuals not belonging to these groupings are typically designated as “out-groups [

16]”. Colleague perceptions rely on a classification system that subsequently influences attitudes and behavior in professional settings.

In-group and out-group dynamics are fundamental to SCT and significantly influence professional interactions. Due to their favorable perceptions of each other, in-group members frequently foster enhanced communication, support, and collaboration [

8]. This strong connection inside the in-group fosters confidence and may enhance the success of group tasks and collaboration. Conversely, out-group members—individuals who differ from the in-group in certain respects, such as gender or ethnicity—may experience exclusion, undermining trust and social support, and exacerbating poor communication [

16]. Individuals from out-groups may encounter discrimination and intolerance, undermining their self-worth and team-building endeavors.

In Ghana’s public healthcare system, GD may initiate a classification process in which individuals distinguish themselves based on gender identities. Gender disparities may lead healthcare professionals to inadvertently establish in-groups and out-groups, thus affecting team cohesion and overall EP [

17]. Enhanced social connections within the in-group may foster increased collaboration and elevate morale. Conversely, the out-group—likely women employed in a male-dominated field—may encounter exclusionary behaviors that hinder their involvement in team initiatives. Consequently, understanding SCT within this context enhances comprehension of how gender-based social categorization may influence performance, collaboration, and the overall dynamics of gender-diverse teams.

SCT offers a comprehensive examination of the impact of gender diversity on team dynamics and employee performance in Ghanaian public health institutions. Knowledge of the potential challenges posed by in-group and out-group dynamics enables organizations to foster more inclusive environments. Effective workforce diversity management enables healthcare institutions to leverage gender diversity as an asset, enhancing team performance and fostering a more supportive work environment that yields improved outcomes for staff and patients [

18].

Milliken and Martins [

19] initially proposed the SCT, which gained currency after [

20] further developed it. According to Milliken and Martins [

19], workforce diversity can positively and negatively affect employee and job results. Enhanced decision-making abilities and adaptability across various perceptual characteristics make up the positive effect. This study is crucial to the SCT because, in the workplace, categorization might result in exclusion and discrimination based on membership in a certain group. As a result, it is the responsibility of management to create policies and strategies to address worker diversity and alter organizational behaviors, empowering them to make a positive change.

2.2. Concept of Diversity Management

Even after 30 years of intense debate, the term ‘diversity’ in the workplace remains ambiguous [

21]. It encompasses a wide range of human resources, including physiological factors like age, gender, and race. Scholars and professionals [

8,

22,

23] argue that staff diversity, above all, is more universal and deserves a distinct perspective.

While some studies advocate for limiting diversity to age and gender, a restricted definition of diversity risks limiting a study to one component of natural variety. This is why further research is crucial. Natural diversity interacts with other aspects of diversity, and ignoring these linkages would limit our understanding of diversity.

As organizations navigate the challenges of a globalized world, the importance of diversity management becomes increasingly evident. Tang [

24] notes that organizations employ diversity management to attract, retain, and develop people of different backgrounds. Gotsis and Kortezi [

25] argue that diversity management should prioritize creating an atmosphere where people can flourish by being themselves rather than assimilating minorities into majority cultures. Wadhwa and Aggarwal [

26] further argue that workforce diversity gives organizations a competitive edge, a crucial advantage in today’s globalized and mobile world.

2.3. Concept of Performance

Behavior distinguishes performance from expected results [

27]. People perform tasks through activities, but results are the product of their effort. Workplace behavior affects the desired outcome, but motivation and cognitive capacity also matter. Performance refers to carrying out the tasks assigned effectively [

28]. It includes success, competitiveness, achievement, activity, and ongoing endeavors to strengthen the present and future.

Performance can be classified into two types: task performance and adaptive performance. When finishing an assignment, the performance includes stated job behaviors and those from the task description [

29]. Task knowledge, skills, and habits drive task performance, which requires increased intelligence. Thus, expertise and completion are the leading indices of task performance. Task performance in an organization refers to the agreement between a manager and a subordinate to complete a task.

In a challenging workplace, adaptive performance means contributing to the task [

29]. After mastering daily tasks, people adapt their attitudes and actions to their professional roles. Staff must adapt to demanding work settings. This includes new technologies, job descriptions, organizational restructurings, and more [

30]. However, technological innovation has created new jobs that require new abilities and adaptability [

31]. In such changed environments, workers must again adjust their interpersonal behavior to work with different colleagues and subordinates. Norms can also improve task performance [

32] suggested workplace adaptation and competitive antagonism to address uncertain business scenarios.

2.4. Gender Diversity

GD is a significant challenge globally, especially in male-dominated sectors such as healthcare. While international conferences often highlight gender parity in corporate boards and technology [

33], the issue of GD in the public healthcare sector—particularly in Ghana—requires greater focus [

8]. Despite the significant presence of Ghanaian doctors, women are occasionally underrepresented in technical fields and leadership roles [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The April USAID [

39]. Ghana Gender Analysis indicates that women constitute the predominant segment of vulnerable workers within the informal economy, mirroring broader socioeconomic dynamics observed in public institutions such as hospitals. Despite increasing female employment, a significant gender disparity persists in the technical and managerial sectors. Entrenched gender norms and restricted opportunities for leadership advancement elucidate the challenges women in Ghana’s healthcare sector face in professional growth.

Diversity management in Ghana’s public healthcare system is still evolving, with limited clear strategies to achieve gender equality. The underrepresentation of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) exacerbates this issue, resulting in a scarcity of qualified women in administrative and medical positions. Ghana’s Public healthcare institutions should explore more effective diversity management strategies since gender diversity increasingly influences creativity, collaboration, and enhanced performance in organizations globally. These strategies must promote gender equality in employment, leadership positions, and professional advancement to foster a more inclusive and sustainable workplace. By addressing these gender disparities, Ghana’s public healthcare system can enhance employee performance, bolster team cohesion, and advance broader objectives of gender equality and inclusive growth as articulated in the SDGs.

2.5. Hypothesis Development

2.5.1. Influence of Workforce Diversity on Employee Performance

The correlation between employee performance and workforce diversity management has garnered significant attention in light of workplace diversity worldwide. The SCT explains this connection by asserting that individuals frequently categorize themselves and others based on evident differences, such as gender, age, and ethnicity. Effectively managed diverse workforces can utilize their diversity to enhance their decision-making, creativity, and problem-solving abilities, thereby contributing to improved workforce performance. This potential for improvement is a reason for optimism in diversity management.

WFDM emphasizes the importance of establishing an inclusive workplace that recognizes the contributions of all employees, irrespective of their origin, and addresses diversity in recruitment. Inclusive diversity management strategies can increase employee engagement and commitment by reducing intergroup biases and fostering a sense of belonging [

40]. This need for inclusivity calls for understanding and empathy in the workplace. According to prior studies, a diverse labor force creates a favorable work atmosphere and boosts employee productivity [

41]. Obeng et al. [

8] reported that an encouraging workplace fosters strong alliances and representations, enhancing worker satisfaction and hierarchical performance.

Further, Li et al. [

42] found that performance and workforce diversity management affect authoritative execution individually. They also say proactive diversity management will inspire the board to extend legitimacy-based activities to increase hierarchical performance. By hiring based on skills and specialization, workforce diversity management gives CEOs variety and increases EP. WFDM maximizes people’s skills to create a perfect workplace [

43]. Lee and Kim [

44] contend that relational coordination links organizational success to employee diversity, with structural empowerment and multisource feedback moderating this connection. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. Workforce diversity management has a positive influence on employee performance.

2.5.2. Influence of Gender Diversity on Employee Performance

Multiple studies, such as those by Devine and Ash [

45] and Perry et al. [

8,

46], have examined the relationship between GD and EP, especially in fostering inclusive and equitable workplaces. The SCT posits that, when skillfully managed, this connection utilizes a range of gender perspectives to enhance team dynamics and decision-making, ultimately leading to improved performance. According to the SCT, establishing in-groups and out-groups based on perceived differences may originally stem from gender variety [

47]. However, implementing coordinated management strategies that promote inclusion can transform these initial divisions into collaborative and efficient teams.

GD offers companies a broader array of thoughts, viewpoints, and problem-solving techniques, leading to more inventive solutions and enhanced productivity. Recognizing and valuing the distinct contributions of employees in gender-diverse settings can lead to increased empowerment and engagement, hence improving motivation and commitment to the organization’s goals [

48]. Therefore, if the organization effectively manages diversity to reconcile initial divisions and create common goals among all members, equitable gender representation may positively influence EP.

GD in the workplace can provide organizations with a competitive edge by attracting a wider pool of talent and leveraging diverse skills and abilities, resulting in increased productivity [

49]. However, the potential for psychological and physical differences between genders could negatively impact employee performance [

50]. For instance, perceiving that specific roles favor one gender over the other may engender feelings of discrimination, demotivating employees and ultimately harming the organization’s overall performance.

Mixed findings have come from research on the connection between GD and EP. While some research has identified a strong correlation between gender diversity and worker performance, other studies have found conflicting results. For instance, a study by Chaudhry and Sharma [

51] on gender and ethnicity diversity in Indian IT companies revealed a significant effect of GD on EP. Similarly, Chepkemoi et al. [

52] found a positive relationship between GD and EP in the County Government of Bomet, Kenya. Sekulic et al. [

53] also found that organizations that have promoted women into executive positions have experienced increases in strategic-level management standards.

In contrast, Noland et al. [

54] investigated the effects of GD in the workplace and found no discernible variations in the jobs performed by men and women within the company. Based on the previous discussion, we can infer the following:

H2. Gender diversity influences employee performance.

2.5.3. Moderating Effect of Gender Diversity in the Relation Between Workforce Diversity and Employee Performance

GD may affect the effectiveness of diversity policies in improving performance outcomes [

55]. Gender diversity influences the WFDM–EP relationship, suggesting that the firm’s level of GD may impact the effectiveness of workforce diversity management activities on EP. WFDM programs may prove more efficacious in workplaces with greater GD, as diverse perspectives and competencies promote a collaborative and inventive work atmosphere. The benefits of diversity management in terms of performance may be less evident in settings with limited gender diversity [

56]. This could be attributed to the absence of diverse perspectives and ideas.

This moderation effect aligns with SCT, which asserts that individuals instinctively classify themselves and others based on visible differences, such as gender, thereby influencing group dynamics and performance. According to SCT, GD within a corporation can create subgroups that, when managed effectively, can harness positive intergroup dynamics to enhance productivity and performance. This indicates that the ability of an organization to capitalize on the benefits of WFDM programs is mainly dependent on the GD of its workforce, as varied groups can provide a broad spectrum of ideas and experiences that may lead to enhanced performance.

One component of workforce diversity is gender diversity, which can interact with other factors in various ways. In contrast, the absence of women or a lack of support for gender diversity can undermine diversity efforts [

57]. For instance, research suggests that having women in leadership positions can positively impact diversity management practices and outcomes.

This study uses GD as a moderator to examine how workplace diversity influences employee performance. GD in the workplace increases employee skills and experiences [

58]. Greater GD in the workforce gives employees different viewpoints, which helps develop and implement corporate strategy. Positive GD often helps an organization outperform competitors and boost production by attracting both sexes and tapping into various skills and capacities. Men and women in teams bring different perspectives and strategies from their life experiences [

59,

60]. We developed the following theory in light of the ongoing discussion:

H3. Gender diversity moderates the influence of workforce diversity on employee performance.

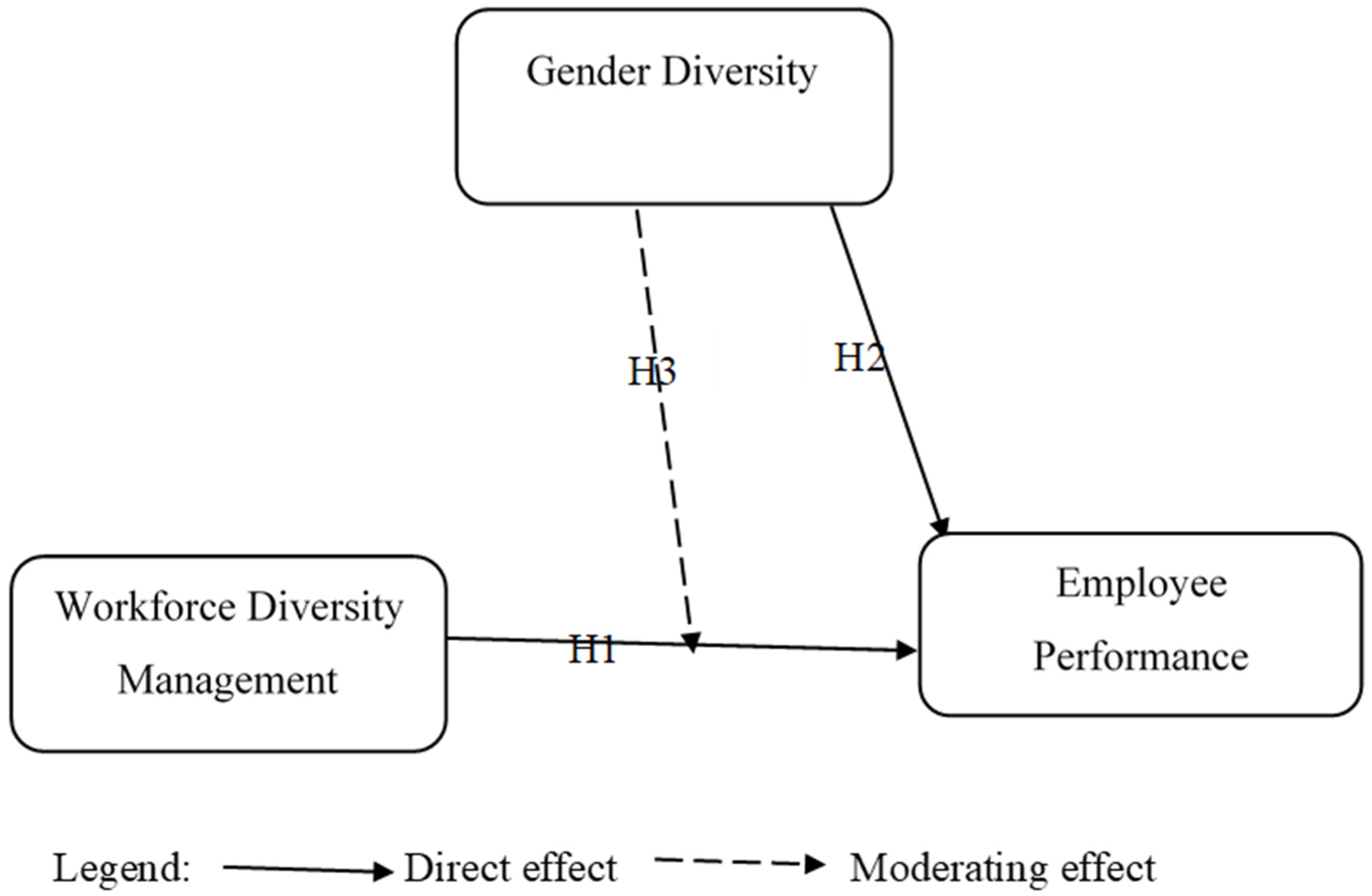

The model presented below was constructed based on hypothesis formulation and a literature review (

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design, Study Population, Sampling Technique and Sample Size

This research utilized a quantitative descriptive methodology to assess and quantify the correlations between WFDM, GD, and EP. This methodology emphasizes the methodical gathering and assessment of quantitative data. This design facilitates the objective analysis of variables and yields measurable insights into the influence of GD and diversity management techniques on performance outcomes in public hospitals in Ghana. The quantitative descriptive method utilizes statistical analysis and structured surveys to discern patterns and correlations in the data, clearly and concisely depicting trends and relationships [

61,

62]. This method is ideal for evaluating the impact of GD and WFDM on EP, facilitating the formulation of generalizable findings to guide diversity initiatives in comparable healthcare settings.

This study selected participants from public hospitals in view of the fact that they deliver vital services to a varied populace. Nonetheless, they often face distinct issues from elevated patient numbers, constrained finances, and heterogeneous staff demographics. This study effectively documents diversity dynamics where cooperation and efficient collaboration are crucial for delivering high-quality patient care. Furthermore, choosing public hospitals offers significant insights into the diversity management practices of businesses governed by regulatory frameworks, potentially aiding the execution of policy-oriented diversity initiatives. This focus guarantees that the findings are contextually relevant and applicable to similar public healthcare settings, equipping policymakers and administrators with essential insights to enhance workforce diversity initiatives in Ghana’s healthcare sector.

Cochran’s [

63] methodology, a popular method for calculating sample sizes when the population size is unknown, established the sample size for the study. This method guarantees that the sample is statistically representative and can accurately estimate population parameters, even when the population is undefined. The formula is estimated as follows:

“

n” is the required sample size, “

Z” is the

Z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level, and “

e” is the desired margin of error.

We collected the data using a snowball sampling technique, where the initial participants recruited additional respondents from their networks. This strategy is especially advantageous for reaching persons who are dispersed or hard to find within the designated hospitals; however, it is also vulnerable to homogeneity bias and selection bias. Selection bias may result in a sample that lacks diversity if the original participants recruit people who are predominantly similar to themselves. Homogeneity bias may occur when the respondent network is overly uniform, limiting the study’s capacity to gather various opinions. The inquiry employed various methods to alleviate these biases. Initially, we set precise criteria for selecting the first participants to ensure a diverse representation of roles and experiences within the institutions.

We urged participants to suggest individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds and departments to enhance the diversity of the sample. Finally, the inquiry assessed the variety of replies during the recruiting process, implementing modifications to guarantee the representation of varied perspectives. Computer-assisted web interviewing enabled the rapid online distribution and collection of the data. This improved accessibility and response rates in a demanding healthcare context. We collected 392 valid responses, surpassing the sample size that Cochran’s technique predicted. Thus, the definitive sample size of the study comprised 392 participants. The elevated response rate augments the statistical power and dependability of the study, facilitating more assured findings about the correlation between employee performance, gender diversity, and workforce diversity management in Ghana’s public hospitals.

The survey had 392 respondents; 228 (58%) identified as female and 164 (42%) identified as male. This gender distribution defines the healthcare sector in Ghana. Most of those in the male sample occupied senior management and leadership positions within the public healthcare system. Conversely, women, comprising a lesser proportion of the workforce, predominantly occupied administrative, support, and nursing roles. This gender-based job inequality highlights the persistent leadership gap and elucidates the issues of gender diversity in Ghanaian public healthcare institutions. The predominant age group among respondents was 31 to 40 years, with 176 individuals (45%), while a lesser number of respondents were aged 41 to 50 (59 individuals, 15%), and 39 individuals (10%) were over 50 years old. In total, 118 respondents, or 30% of the total, represented the 20–30 age group. Regarding education, 118 persons (30%) possessed bachelor’s degrees, but the majority (196%) had earned simply a diploma. The predominant segment of the workforce possessed mid-level qualifications, as indicated by the 39 (10%) individuals with certificates, contrasted with the minority of 27 (7%) and 12 (3%) individuals holding master’s and doctoral degrees, respectively. Of the respondents, 176 (45%) were married, whereas 216 (55%) were single, according to their marital status. These demographics frame the study’s conclusions regarding diversity management and employee performance, providing a representative view of the workforce in Ghana’s public hospitals.

3.2. Measures and Scale

We adapted questionnaires from recognized scales in the literature to ensure the validity and reliability of assessing the key variables in WFDM, GD and EP (refer

Appendix A). We adapted the WFDM questionnaire from O’Keefe et al. [

64] for Ghana, as it prioritizes good communication and inclusive practices, essential in the diverse settings of public hospitals. The instrument’s structure aligns with the distinct issues faced by Ghana’s healthcare sector due to the variety of cultural backgrounds and viewpoints present.

Adapted from Chepkemoi et al. [

52], the GD scale exhibits a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.895, suggesting its high reliability. This scale is suitable for use in Ghana due to its accurate representation of the subtleties of gender representation in the workforce and its reflection on the dynamics present in public hospitals.

Chepkemoi et al. [

52] presented the scale items on EP, and their Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of over 0.850 indicates a high level of reliability. This scale is suitable for use in Ghana because it accurately measures performance indicators relevant to public hospitals’ unique demands and challenges. This study utilized a five-point Likert scale, according to Nyarko et al. [

65]: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5). The grade scales attached to each question enabled personnel from different banks to assess it according to its implementation in their institutions.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study selected the statistical software SMART PLS (version: 4.1.0.8) because it can evaluate direct and indirect relationships among variables. This tool is especially advantageous for structural equation modeling (SEM), enabling researchers to evaluate intricate relationships and interactions within their data [

66]. In line with previous research by Hair et al. [

67] and Obeng et al. [

68], we evaluated the moderating effect using the bootstrapping method, which includes 5000 iterations and a 95% confidence interval. Generating empirical findings from the estimated parameters enhances the trustworthiness of the results, enabling more precise conclusions about indirect impacts.

The Partial Least Squares (PLSs) algorithm and its intuitive interface set SMART PLS apart from other statistical tools [

69]. Business research and the social sciences commonly use this technique due to its remarkable ability to assess intricate models with numerous variables and indicators while accommodating tiny sample numbers. The findings’ capacity to precisely forecast route coefficients and loadings enhances their trustworthiness [

70].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model

Table 1 shows the results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which uses SRMR and NFI to check if the measurement model is adequate. An SRMR of 0.054 signifies a well-fitting model that integrates variable connections with small residuals, remaining below the 0.08 threshold [

70,

71]. The NFI score of 0.92, which exceeds the acceptable threshold of 0.90, further confirms the satisfactory model fit. These values indicate that the measurement model accurately represents the relationships among variables and aligns with the observed data.

4.2. Reliability and Convergent Validity

Table 2 summarizes the reliability and convergence validity ratings. The construct dependability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (

α) and composite reliability (CR), with values surpassing 0.70 signifying strong reliability [

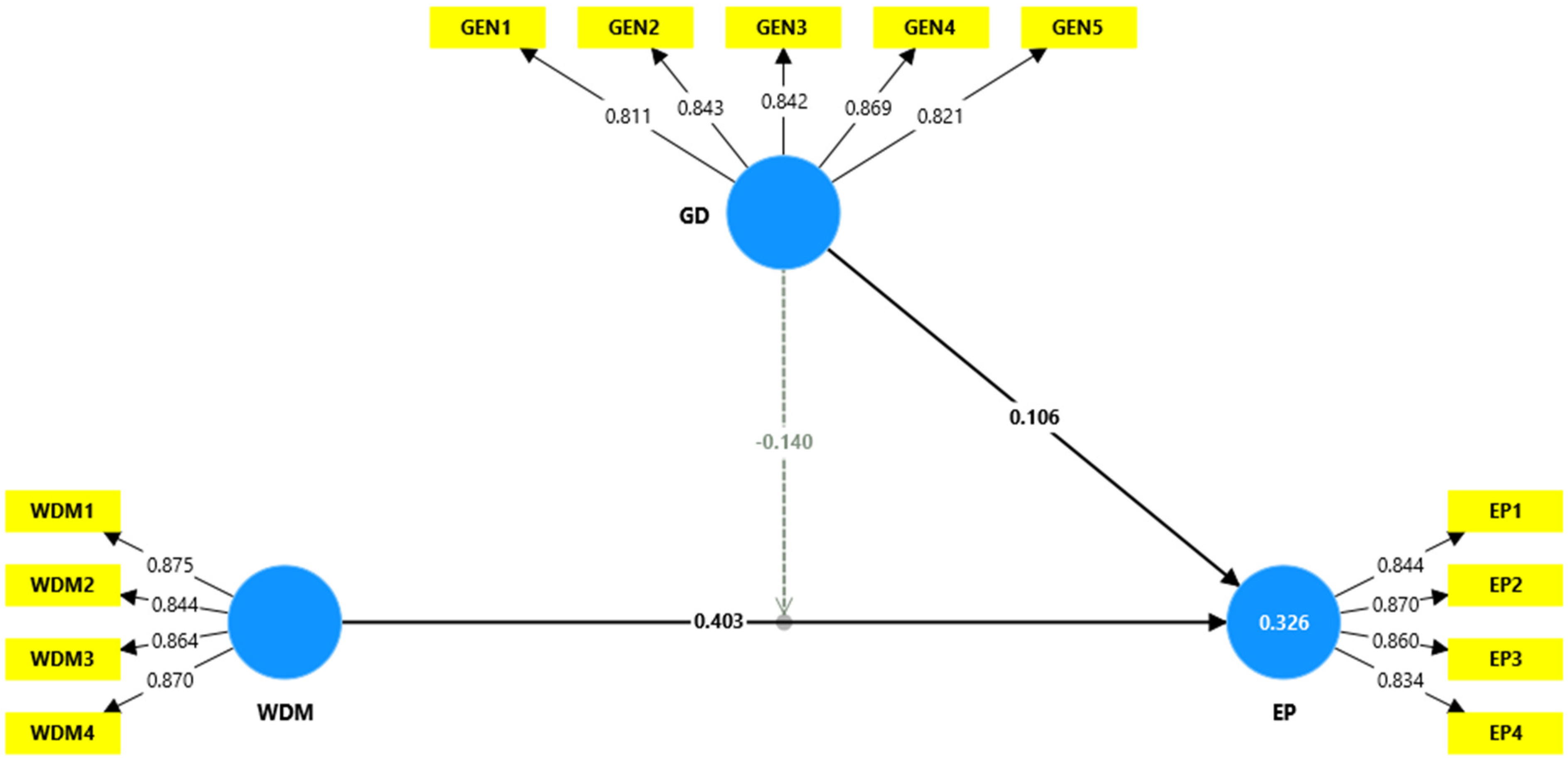

72]. The internal consistency of each construct was adequate and surpassed this requirement. A convergent validity test required standardized loadings (see

Figure 2) of more than 0.70 and average variance extracted (AVE) values of more than 0.50, and we used AVE and standardized loadings. We omitted EP5 and other items with loadings under 0.70. The instrument exhibited convergent validity, with AVE and loadings meeting the established norms across constructs at the specified levels.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Table 3 presents a discriminant validity study utilizing the Fornell–Larcker [

73] criterion and the HTMT ratio. Rönkkö and Cho [

74] suggest that the HTMT ratio, which measures the average correlations among items within the same concept and across constructs, exhibits adequate distinctiveness when it falls below 0.9. All HTMT ratios in this study fell below this threshold, which validated the uniqueness of the construct. We use the Fornell–Larcker criterion to evaluate the square root of the AVE about inter-construct correlations. The diagonal values (square root of AVE) highlighted the uniqueness of the constructs, surpassing the off-diagonal correlation values. The AVE for EP was 0.852, whereas the correlations with GD and WFDM were lower at 0.395 and 0.514, respectively.

4.4. Structural Model Fitness Assessment

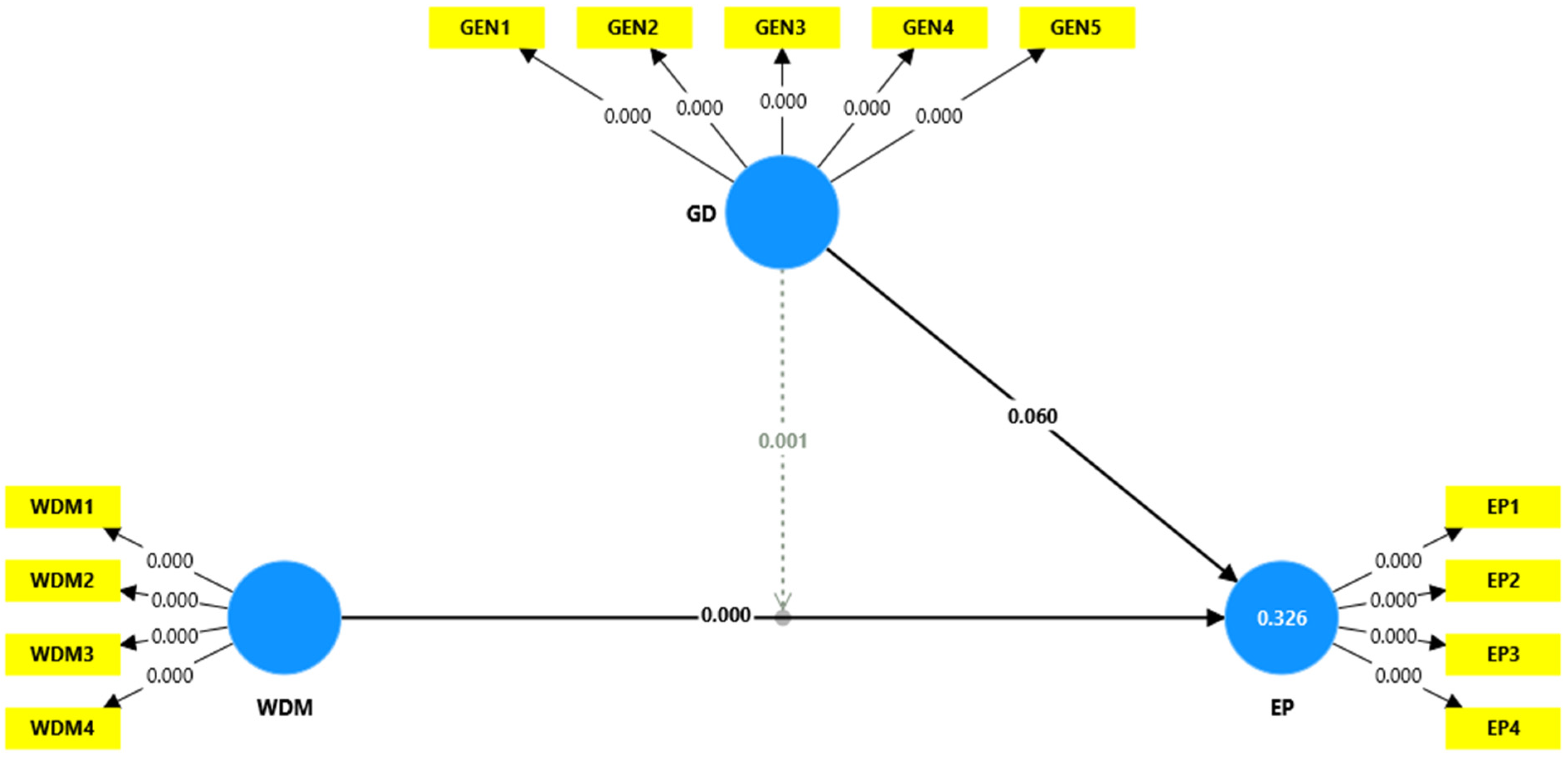

Prior to formulating management and theoretical conclusions from the structural model, certain essential criteria were met to guarantee reliability. We meticulously satisfied the criterion that all loadings were statistically significant, as shown in

Figure 3. The findings of a bootstrapping study, which employed 5000 samples at a 95% confidence level, validate the robustness of the model, as illustrated in this figure. These results confirm the dependability of our findings, meeting all criteria and enabling a solid interpretation of the model’s output.

We thoroughly analyzed the subsequent criterion, which evaluated the extent of collinearity among variables. The inner values significantly fell below the 3.3 threshold proposed by Salmerón et al. [

75], indicating the absence of collinearity concerns. This improves the model’s ability to reliably and precisely analyze the relationships among variables.

The variance in EP may be explained by independent variables, as indicated by an R

2 (see

Table 4) value of 0.326. This indicates that the model’s predictors explain around 32.6% of the variance in EP, signifying a modest level of explanatory power. This is beneficial, but it also indicates that the model’s ability to clarify EP may improve with the incorporation of further variables.

The Q

2 value of 0.301 was utilized to evaluate the predictive usefulness of the model through the blindfolding procedure. The model’s predictive accuracy for EP is adequate, as Q

2 exceeds zero. A favorable Q

2 score indicates the model’s robustness by showcasing its capacity to predict outcomes and identify correlations within the data [

76,

77]. The R

2 and Q

2 metrics validate the model’s capacity to explain and forecast EP. They propose that exploring additional components may be significant for capturing a broader range of variance.

The effect size (f

2) (refer

Table 5) in the model measures the effect of each predictor on the dependent variable. An f

2 value of 0.02 is deemed small, 0.15 is medium, and 0.35 is high. The f

2 value of the study regarding the correlation between GD and EP is 0.011, indicating a minimal influence. This suggests that GD does not significantly impact EP on its own. Conversely, WDM exhibits a modest effect size (f

2 = 0.189). This indicates that WDM is a more dependable predictor of EP and significantly influences performance outcomes. The interaction effect of GD and WDM exhibits a minimal impact size, as evidenced by an f

2 value of 0.044. This indicates that, although GD functions as a moderator in the WDM–EP interaction, its influence is very limited.

4.5. Common Method Bias

Arhinful et al. [

78], Arhinful et al. [

79], Mensah and Bein [

80] and Arhinful et al. [

81] utilized the variance inflation factor (VIF) (see

Table 6) as a diagnostic tool to address Common Method Bias (CMB), a data collection concern intensified by multicollinearity that can amplify correlations across variables. The study utilized the variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess the validity of this issue, and

Table 6 reveals that all inner VIF values fell below the established threshold of 3.3 [

75,

76]. These findings validate the study’s data by addressing CMB-related issues and demonstrating that variable relationships are not significantly affected by shared method variance and multicollinearity. The structural model’s robustness in validating the acceptance or rejection of a hypothesis is substantiated by the combined Q

2, f

2, R

2, and VIF metrics. These measures highlight the model’s reliability and affirm that its conclusions are unbiased and valid.

4.6. Hypothesis Testing

Table 6 and

Figure 4 display the findings of the H1 and H2 direct effects, and H3 moderating effect. H1 asserted that WFDM significantly and positively influences EP (β = 0.402,

t = 5.278,

p < 0.01). The findings of this study revealed a significant and positive influence of WFDM on EP. As a result, H1 was accepted.

Furthermore, the hypothesis (H2) that GD significantly and positively influences EP was confirmed. The findings of the study demonstrated an infinitesimal significant positive effect of GD on EP (β = 0.106, t = 1.559, p < 0.1).

In addition, H3 posits that GD moderates the relationship between WFDM and EP. According to the statistical analysis, the results are statistically significant (β = −0.140, t = 2.988, p < 0.05). H3 was therefore approved.

5. Discussions of Findings

This finding supports the current evidence that WFDM affects EP through a GD-moderated interaction mechanism. The study’s first results demonstrated that WFDM significantly and positively influences EP. This suggests that initiatives to manage workplace diversity proficiently could enhance EP engagement and productivity. Active acknowledgment and integration of employees’ varied viewpoints, backgrounds, and experiences improve performance outcomes, leading to increased respect and motivation. The findings of this study support the report of Selvaraj [

82], who identified a significant and positive effect of WFDM on EP.

The findings of this study provide additional evidence in favor of the SCT. This implies that efficient implementation of WFDM may enhance employees’ sense of cohesion and inclusion despite their diverse backgrounds. This diversity management strategy benefits SCT by fostering a collective identity among employees, promoting collaboration and reducing biases that may hinder production. Employees’ heightened motivation and commitment, when they perceive themselves as valued and included in this setting, improve employee performance.

WFDM positively influences employee performance, and managers ought to advocate for diversity efforts by executing inclusive recruitment and retention tactics. Regular team-building activities and training sessions are essential to elevating awareness of diversity and its capacity to improve performance. To maximize the benefits of diversity, managers must implement mentorship programs and encourage employees from diverse backgrounds to participate in decision-making processes.

Additionally, the findings of this study revealed a significant marginal positive effect of GD on EP. This study suggests that performance improvements may be negligible rather than significant due to gender diversity. Although this effect may necessitate supportive organizational strategies to actualize its advantages fully, it suggests that a balanced representation of gender in the workforce can provide unique perspectives and skills that improve overall performance [

83]. The findings of this study align with those of Setati et al. [

84], who examined a higher education institution in South Africa and discovered that GD significantly improved staff performance. This consistent approach highlights the potential benefits of gender diversity across many organizational and cultural contexts and the belief that it enhances employee performance.

This study reinforces SCT. SCT posits that diversity, particularly GD, can improve performance outcomes when individuals recognize and leverage their unique strengths across different businesses. This study’s findings indicate that GD markedly enhances EP, supporting SCT’s assertion that team diversity promotes a variety of viewpoints and contributions and, therefore, improves efficiency. This illustrates that gender diversity can be lucrative in organizational settings, consistent with SCT’s intergroup dynamics and identity theory.

GD exerts a reasonably positive influence on EP; hence, its advancement, especially in leadership positions, may enhance overall performance. Managers must provide equitable chances for both genders and encourage women to develop their leadership skills. To enhance performance outcomes, managers should prioritize gender-balanced teams and implement equitable, transparent policies that promote women’s advancement within the business.

Finally, the study demonstrated that GD negatively moderates the relationship between WFDM and EP. This implies that while WFDM frequently enhances EP, its impact on EP might diminish in environments with substantial gender diversity. This adverse moderation indicates that gender diversity may pose challenges in the workplace, thereby affecting the efficacy of diversity management activities for realizing performance targets [

85]. Hospitals should adjust their workforce diversity management strategies to address potential challenges related to gender diversity, as suggested by this study. This ensures that diversity programs improve performance without consciously establishing barriers that reduce effectiveness.

This study’s findings strengthen the SCT. SCT asserts that individuals often define themselves and others by using common social identities, such as gender. High gender diversity may lead employees to self-segregate into gender-specific groups, affecting collaboration and cooperation. Diverse social identities can sometimes undermine the cohesiveness and inclusivity that WFDM activities seek, thereby affecting overall performance outcomes [

86].

Managers must acknowledge that overemphasizing gender inequalities can lead to team strife. To promote collaboration over conflict, it is essential to create an environment that embraces gender diversity and other features of variety, such as ethnicity. By promoting collaboration and transparent communication, managers can avert the establishment of gender-based silos.

6. Conclusions

This study assessed the influence of WFDM on EP, considering the moderating role of GD in this relationship. It used a quantitative design and snowball sampling technique to obtain data from 392 participants. SMARTPLS4 was used to analyze the direct and moderating relationships among the variables.

This study identified a significant and positive effect of WFDM on EP. Similarly, it showed a significant positive impact of GD on EP. Finally, it revealed that GD moderates the relationship between WFDM and EP. The findings of this study have essential theoretical and managerial implications.

7. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study are of significant theoretical importance as they enhance the SCT within the context of workforce diversity management. According to SCT, individuals categorize themselves and others based on prominent characteristics such as gender, influencing interpersonal dynamics and organizational outcomes. Consistent with the foundational research of Turner and Tajfel [

87,

88], our results indicate that gender diversity enhances employee performance through improved cooperation, creativity, and decision-making. The identified moderating effect—where gender diversity diminishes the direct relationship between workforce diversity management and employee performance—aligns with Hogg and Terry’s [

89] idea that categorization systems can enhance or detract from group cohesiveness, contingent upon the context.

This study examines Ghana’s public healthcare system. It provides empirical data illustrating how various cultural and institutional contexts influence social categorization outcomes, enhancing the conclusions drawn by Shore et al. [

90] regarding the necessity of inclusion policies. Our findings suggest that, although diversity possesses significant potential to enhance performance, neglecting subgroup dynamics may limit its benefits. Van Knippenberg and Schippers [

91] assert that reconciling in-group and out-group disparities relies on effective diversity management strategies. This research enriches the SCT framework by underscoring the necessity of targeted inclusion programs to optimize the advantages of diversity and by empirically demonstrating the dual aspects of social categorization in gender-diverse organizations.

8. Managerial Implications

The findings present managerial implications for improving hospital administration performance through effective diversity management. Managers must emphasize the execution of holistic diversity initiatives, as demonstrated by the positive impact of workforce WFDM on EP. We can harness the benefits of a diverse workforce by employing consistent diversity training, impartial recruitment strategies, and cultivating a collaborative workplace culture.

The moderately beneficial effect of GD on EP highlights the importance of managers establishing gender-balanced teams to guarantee equitable chances for all employees. Enhancing gender diversity allows managers to access diverse viewpoints and skills, improving their decision-making and problem-solving strategies.

However, the negative impact of GD on the relationship between WFDM and EP suggests the need for specific approaches to address issues that arise in teams with members from diverse backgrounds. Managers must implement inclusive communication channels and conflict resolution processes to promote effective collaboration. Implementing mentorship programs will increase cohesiveness by fostering integration and mitigating interpersonal tensions from varied backgrounds. These consequences highlight the imperative for hospital administrators to tailor their actions when implementing diversity policies to ensure that diversity positively influences team chemistry and productivity.

9. Implications for Human Resource Practitioners

In Ghana’s public healthcare system, human resource managers should prioritize structured diversity programs, as gender and workforce diversity significantly enhance employee performance. Initially, particularly in senior roles where underrepresentation is most evident, organizations should implement comprehensive diversity management plans that promote gender equality throughout all employment tiers. Tailored recruitment, mentoring, and leadership development programs designed to empower female employees may enhance the advantages of gender diversity on employee performance. Secondly, HR managers must ensure that diversity initiatives are not merely symbolic but are deeply embedded in the business culture, as GD has been shown to negatively, however slightly, affect the WFDM–EP relationship. This objective would be advanced through regular diversity assessments, bias training, and inclusive team-building initiatives, thereby diminishing out-group dynamics and fostering cohesive, high-performance teams. Public healthcare firms can enhance staff performance and service delivery by implementing targeted human resource management techniques that optimize diversity.

10. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study provides significant insights into the relationship among WFDM, GD, and EP, although it has some shortcomings. The conclusions may initially have limited relevance despite 392 individuals representing an adequate sample size. Employing a larger and more diverse sample would strengthen the conclusions and offer greater insights across many contexts. Second, the study’s use of a quantitative research method may not fully capture the complex, qualitative aspects of diversity dynamics and how they affect employee performance, even though this method is useful for finding links between variables. Qualitative approaches, like interviews and focus groups, can enhance our understanding of the interpersonal and cultural factors that influence heterogeneous teams.

Moreover, the snowball sampling technique, while advantageous for targeting a specific group, may induce sampling bias and limit sample variety. Future research should employ random sampling methods to improve representativeness and reduce potential bias. To gain a more thorough understanding of the influence of diversity management on employee performance, subsequent research should investigate these linkages across other organizational contexts, industries, and cultural environments. Furthermore, longitudinal research may provide more thorough insights into the long-term effects of WFDM and GD, as opposed to the cross-sectional method utilized in this study.

While providing valuable analysis, this study is constrained by its focus on GD rather than broader concepts such as gender inclusion or comprehensive diversity management strategies. Subsequent research should consider expanding the conceptual framework to integrate gender inclusion and diversity management, including a broader spectrum of organizational tactics and employee experiences. This would yield a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of inclusive policies on staff performance inside public healthcare institutions.