More than Just a Roof: Solutions to Better Support Families from Homelessness to Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Present Challenges Faced by Families When Navigating the Homelessness Service Sector

1.2. Consequences of Poor Service Provision for Families Experiencing Homelessness

1.3. Continued Gaps in Service Provision and the Consequences for Canadian Families

1.4. Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

Study Setting

2.2. Participants

Description of Our Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

Data Saturation

3. Results

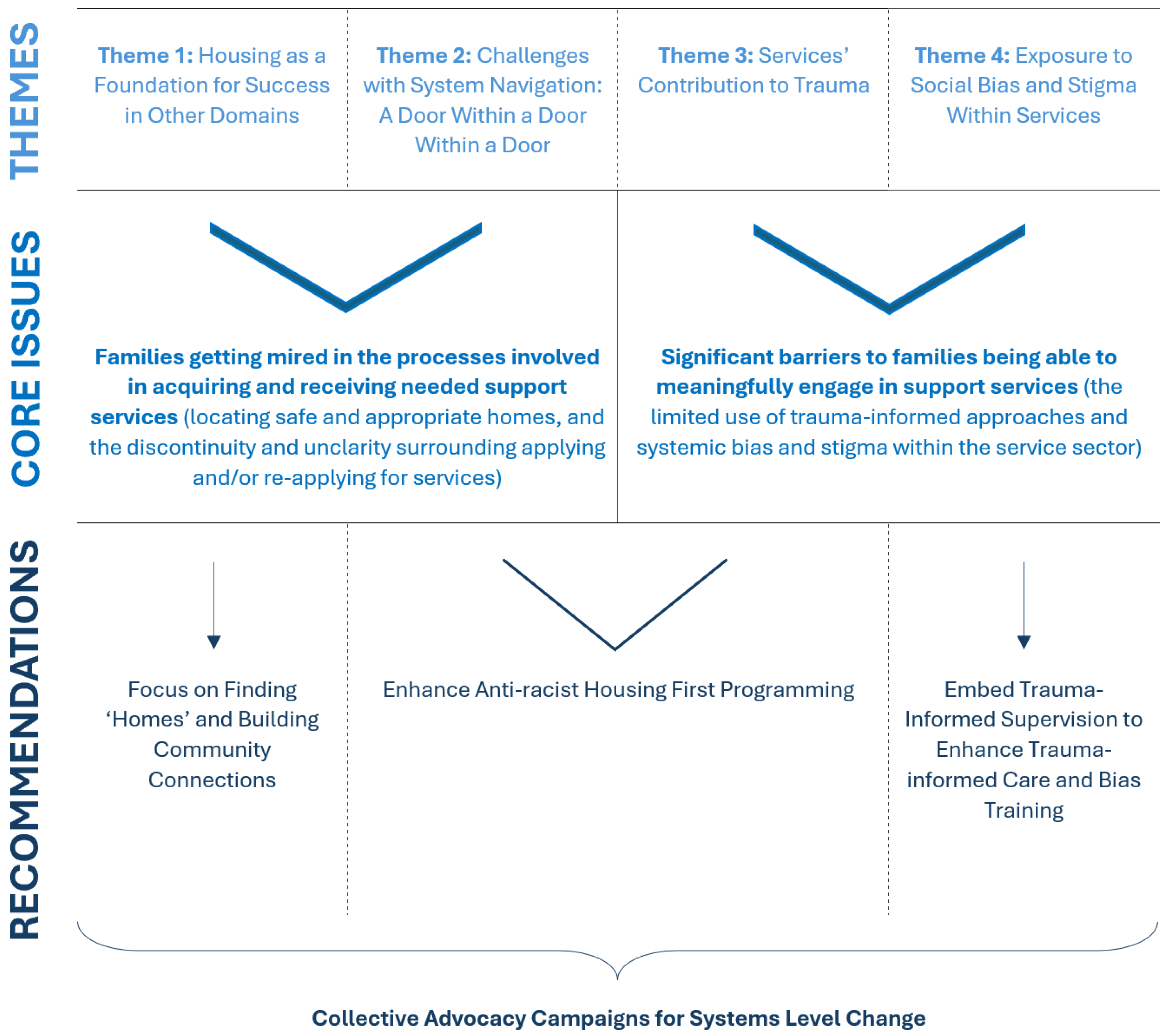

3.1. Housing as a Foundation for Success in Other Domains

“Secure, safe and comfortable housing is like the gateway. Not necessarily for gaining access, but certainly having success addressing all the other challenges they face. Without it (housing) they are so much higher risk.”Staff interview

“Housing is so important. They can’t be expected to deal with all the other things in their lives, family reunification, holding a job, their mental health, if they don’t have some place of their own to return to at the end of the day.”Staff interview

“When I came to the shelter, they said three months was max to stay. That that would give me plenty of time to find a good place. I called Affordable Housing right away and they said the wait list was something like a year to get any type of place. My daughter and I moved three times while we waited to get to the top of that waitlist. This place still isn’t what I want, but shelters aren’t an option for me anymore.”Parent 4

“They hold that over you, and in some ways its good y’know. Keeps me focused on them [their children], not just me. But if they take my kids again because I lose this place, or can’t find a new one I will have lost everything… like I might as well just pack it all in.”Parent 14

“I need to keep this place to prove I can provide for my kids. But it’s more than I can afford, really, and I keep getting denied custody, so it gets to feeling kind of hopeless.”Parent 14

“We need safe and stable housing for them to feel safe. To feel secured and to feel loved and to thrive.

[Then] we can become a family that is thriving, living not just surviving. We’ve been in survival for a long time. My dreams are so that we can be a family with all these supports even with all these ups and downs so that we can teach and problem solve together. So that when big things come up we can cope as a family.”Parent 13

“A landlord liaison develops relationships with landlords. So that if there’s a client that needs a three bedroom house has a dog, has no references, and maybe not a pretty picture for a landlord, there would already be a relationship so that he could say, this is a family we work with, we will be providing subsidies, someone will be in the home once a month, to make sure that your property is at least being looked at…”Staff interview

3.2. Challenges with System Navigation: A Door Within a Door Within a Door

“No one talks to each other or works together. Like you would think if housing is required for [children’s services], then they would work together, but they just don’t.”Parent 1

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve completed multiple application forms for clients that ask the same questions in the same format, and they are going to the same governmental departments to boot. Each service seems to still want their own form. It’s so time consuming, and pretty exhausting for some of our clients. Having to rehash some of that stuff over and over again. I don’t even think it’s healthy for some of them.”Staff interview

“I need [government social assistance] just to get onto the waitlist for affordable housing, but I got a little one, right? No way could I make rent and pay for daycare too. What I do get is better if I stay home with her in a shelter or something like that. Makes no sense to me that I need one to get the other.”Parent 3

“My partner and me, we both get [government disability benefits], but we can work. Like we would like to work. But if we do, then that comes off our [benefits] money so we can’t get ahead either way.”Parent 6

“It’s kind of like putting the cart before the horse. They can’t get into a home until they have a job, but they can’t get a job if they don’t have somewhere to go home to.”Staff interview

“We used to have workers in community resource centers several years ago, a person could come in, just say, I need a food bank referral… can you help me fill out an application like something around very much basic needs, There’s very few places you can go as part of a holistic support… we’re not funded to do that.”Staff Interview

“What if 10% of our budget was for flexible spending… Whatever that family needs that month… once it may be clothes for their kids, medicine…”Staff Interview

3.3. Services’eContributions to Trauma

“They don’t realize how much it rips my heart out when they say stuff like ‘If you don’t comply you could get your kids taken away’. Like they say it so easily. I’m a human being, even just suggesting stuff like that sends me into a complete tailspin. It’s terrifying.”Parent 2

“I’m a proud man, so some of this is hard. Like needing what feels like handouts and such. Most folks are pretty nice once you’re like ‘in’ for their program, but getting ‘in’ like, man, I’ve been treated like shit and told I’m a bad dad… it would be so much easier to just say f**k it and go back to my old life. But I do it for my kids, everything is for them. Everything!”Parent 5

“Every time I get a new worker if feels like I’m back at the starting line. Like having to re-explain what I use the money for and why I need it. It’s hard, like I’m a pretty positive person, try to always look ahead, one foot in front of the other y’know? Rehashing all that stuff though… it can be rough sometimes.”Parent 15

“They make you feel like we’ve done something bad and are just looking for free handouts… it’s not that way at all. We drove all the way here to make a better life for our family… we just need like a ummmm… a boost… yeah, a boost to get us started… we don’t plan to need the help for long.”Parent 7

“Generally, I do feel there is a prevailing philosophy within the income support system but also within children services that does not align with being trauma informed. There is still this assumption that we see within all these systems… that it is the families’ responsibility for their own circumstance and its their responsibility to fix it. There isn’t a trauma informed lens to this work enough which leads to missing a lot of things… we can appreciate there is a natural consequence to individual choices but we don’t see there are underlying circumstances that lead to this.”Staff Interview

3.4. Exposure to Social Bias and Stigma Within Services

“My neighbors think I’m crazy, so they watch me all the time, and call my landlord on me at least once a week”.Parent 15

“Yeah, landlords, they don’t rent their places to people like us. They take one look at us and all of a sudden, ‘oh, the place is already taken.’”Parent 12

“It’s just me and my three kids, we keep to ourselves. But the guy tells me he won’t tolerate the loud parties and drinking that ‘you people’ like to have.”Parent 13

“Some families experience discrimination… sometimes their name triggers a landlord not responding, or their grammar, all these things that don’t make any sense with regard to whether you’re appropriate for housing.”Staff Interview

“A landlord liaison develops relationships with landlords… So to have someone [landlord liaison] that can help them navigate that. Because it’s really hard. Some families experience discrimination… sometimes their name triggers a landlord not responding, or their grammar, all these things that don’t make any sense with regard to whether you’re appropriate for housing.”Staff Interview

“They told us as soon as we walked in, like didn’t know us or nothing, just ‘no smoking up the house’. At first, I didn’t get it, I said no we don’t smoke, but like then he said it again like I was deaf or something; ‘no, no smoking the house or ritual stuff you know you all do.’ I finally figured out he meant I couldn’t smudge. I’m not saying we would or wouldn’t smudge but by that time that wasn’t really the point.”Parent 8

“The cultural competency piece of understanding that Indigenous systems of family and community are different from colonial systems, family and community, and I’ve seen it over and over again… It’s kind of this really messed up loop that happens where you’re being told [culture is important] but then they get penalized… like not being able to hold ceremony in the home or house larger families or have visitors…”Staff interview

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Policy and Service Delivery

4.1.1. Focus on Finding “Homes” and Building Community Connections

4.1.2. Enhance Anti-Racist Housing First Programming

4.1.3. Embed Trauma-Informed Supervision to Enhance Trauma-Informed Care and Bias Training

4.1.4. Collective Advocacy Campaigns for System-Level Change

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaetz, S.; Donaldson, J.; Richter, T.; Gulliver, T. The State of Homelessness in Canada; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz, S.; Barr, C.; Friesen, A.; Harris, B.; Hill, C.; Kovacs-Burns, K.; Pauly, B.; Pearce, B.; Turner, A.; Marsolais, A. Canadian Definition of Homelessness; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Calgary Homeless Foundation. Calgary Point-in-Time Count Report; Calgary Homeless Foundation: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gültekin, L.; Brush, B.L. In Their Own Words: Exploring Family Pathways to Housing Instability. J. Fam. Nurs. 2017, 23, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sylvestre, J.; Kerman, N.; Polillo, A.; Lee, C.M.; Aubry, T.; Czechowski, K. A qualitative study of the pathways into and impacts of family homelessness. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2265–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, G.M.; Michel, C.L.; Cejudo, G.M.; Michel, C.L. Addressing fragmented government action: Coordination, coherence, and integration. Policy Sci. 2017, 50, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaney, K.; Lockerbie, S.L.; Fang, X.Y.; Ramage, K. The role of structural violence in family homelessness. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gültekin, L.; Brush, B.L.; Baiardi, J.M.; Kirk, K.; VanMaldeghem, K. Voices from the street: Exploring the realities of family homelessness. J. Fam. Nurs. 2014, 20, 390–414. [Google Scholar]

- Milaney, K.; Ramage, K.; Yang Fang, X.; Louis, M. Understanding Mothers Experiencing Homelessness: A Gendered Approach to Finding Solutions for Family Homelessness; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, F.M.R.; Simoes Figueiredo, A.; Capelas, M.L.; Charepe, Z.; Deodato, S. Experiences of Homeless Families in Parenthood: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomicic, S. A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Women Mothering Within the Context of a Shelter. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Netto, G. Vulnerability to homelessness, use of services and homelessness prevention in Black and minority ethnic communities. Hous. Studies. 2006, 21, 581–601. [Google Scholar]

- Distasio, J.; Zell, S.; Snyder, M. At Home in Winnipeg: Localizing Housing First as a Culturally Responsive Approach to Understanding and Addressing Urban Indigenous Homelessness; Institute of Urban Studies: Winnipeg, MB, Canada; Prairie Research Centre: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta. Child Intervention Information and Statistics Summary—2022-23 Third Quarter (December) Update; Government of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, C.; Henderson, R.; Bristowe, K.L.S.; Ramage, K.; Milaney, K. Developing Gendered and Culturally Safe Interventions for Urban Indigenous Families Experiencing Homelessness; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, C.; Quinn, D.M. Stigmatized identities, psychological distress, and physical health: Intersections of homelessness and race. Stigma Health 2018, 3, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.K. Race matters in addressing homelessness: A scoping review and call for critical research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2023, 72, 464–485. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S.; Cutuli, J.J.; Herbers, J.E.; Hinz, E.; Obradovic, J.; Wenzel, A.J. Academic risk and resilience in the context of homelessness. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Harvey, B. Family Experiences of Pathways into Homelessness; Housing Agency: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Forchuk, C.; Russell, G.; Richardson, J.; Perreault, C.; Hassan, H.; Lucyk, B.; Gyamfi, S. Family matters in Canada: Understanding and addressing family homelessness in Ontario. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiah-Mohammed, F.; Oudshoorn, A.; Forchuk, C. Gender and experiences of family homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homelessness 2020, 29, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annor, B.O.H.; Oudshoorn, A. The health challenges of families experiencing homelessness. Hous. Care Support 2019, 22, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Rental Market Report; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada Statistics. Homeless Shelter Capacity in Canada from 2016 to 2023, Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC); Government of Canada Statistics: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cold IFt. Report to Community. 2023. Available online: https://innfromthecold.org/3d-flip-book/report-to-community-2022-23/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Battaglia, R. Alberta Budget 2024: Keeps Fiscal Surplus and Lowest Provincial Debt Burden; RBC: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, A.A.; Harris-Wai, J.N. Stakeholder engagement in policy development: Challenges and opportunities for human genomics. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, I. The focus groups in social research: Advantages and disadvantages. Qual. Quant. 2012, 46, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Acorda, D.; Businelle, M.; Santa Maria, D. Perceived Impacts, Acceptability, and Recommendations for Ecological Momentary Assessment Among Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e21638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, E.R.; Vincent, A.Y.S. Parenting and child experiences in shelter: A qualitative study exploring the effect of homelessness on the parent–child relationship. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 23, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, P.-B.; Blais, M. Between resignation, resistance and recognition: A qualitative analysis of LGBTQ+ youth profiles of homelessness agencies utilization. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayock, P.; Neary, F.; Mayock, P.; Neary, F. “Where am I going to go tonight? Where am I literally going to go?”: Exploring the dynamics of domestic violence and family homelessness. J. Fam. Violence 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwood, O.; Hanemaayer, A.; Saad, A.; Salvalaggio, G.; Bloch, G.; Moledina, A.; Pinto, N.; Ziha, L.; Geurguis, M.; Aliferis, A.; et al. Determinants of implementation of a clinical practice guideline for homeless health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Baron, J.T.; Collins, D. ‘Take whatever you can get’: Practicing Housing First in Alberta. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 1286–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Long, F.; Evans, J. “Doing What We Can with What We Have”: Examining the Role of Local Government in Poverty Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geoforum 2023, 144, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadidzedeh, A.; Kneeebone, R. An Evaluation of Housing First Programs in Calgary; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pass, T.; Dada, O.; John, J.; Daley, M.; Mushquash, C.; Abramovich, A.; Barbic, S.; Frederick, T.; Kozloff, N.; McKenzie, K.; et al. More than a roof and a key required: Exploration of guiding principles for stabilizing the housing trajectories of youth who have experienced homelessness. Youth 2024, 4, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honisett, S.; Hall, T.; Hiscock, H.; Goldfeld, S. The feasibility of a child and family hub within Victorian community health services: A qualitative study. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2022, 46, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Black, E.B.; Fedyszyn, I.E.; Mildred, H.; Perkin, R.; Lough, R.; Brann, P.; Ritter, C. Homeless youth: Barriers and facilitators for service referrals. Eval. Program Plann. 2018, 68, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A.B.; Poza, I.; Washington, D.L. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Women’s Health Issues 2011, 21, S203–S209. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, E.K.; Bassuk, E.L.; Olivet, J. Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. Open Health Serv. Policy J. 2010, 3, 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, D.J.; Beach, M.C.; Saha, S. Mindfulness practice: A promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, J.; Ho, I.; Williamson, A. A systematic review of the effect of stigma on the health of people experiencing homelessness. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borders, L.D.; Lowman, M.M.; Eicher, P.A.; Phifer, J.K. Trauma-informed supervision of trainees: Practices of supervisors trained in both trauma and clinical supervision. Traumatology 2023, 29, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, C.A. Trauma-informed supervision and consultation: Personal reflections. Clin. Superv. 2018, 37, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, H.D. Administrative and clinical supervision: The impact of dual roles on supervisee disclosure in counseling supervision. Clin. Superv. 2014, 33, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.B.; Gillespie, K.C.; Greer, J.M.; Eanes, B.E. Influence of dyadic mutuality on counselor trainee willingness to self-disclose clinical mistakes to supervisors. Clin. Superv. 2003, 21, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, A.R. How to Improve Housing Voucher Utilization: Assessing the Effectiveness of Source of Income Laws and Landlord Incentives; Georgetown University: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Threatt, M.C. Using Input from Landlords Participating in the Dothan Housing Authority’s Housing Choice Voucher Program (HCVP) to Streamline Operations and Increase Retention. Ph.D. Thesis, West Chester University, West Chester, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.J.; Hovmand, P.S.; Marcal, K.E.; Das, S. Solving Homelessness from a Complex Systems Perspective: Insights for Prevention Responses. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 465–486. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Coding Method | Performed by |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Researchers familiarize themselves with the data | P.D., K.M., community partners | |

| 2. Generate initial codes | Inductive approach | P.D., K.M., community partners |

| Iterative process | Consensus-based codebook | P.D., community partners |

| Review | Consensus-based codebook | P.D., community partners |

| Data saturation | Final codebook | P.D., K.M., community partners |

| 3. Searching for themes | Consensus approach based on emergent themes | P.D., community partners, A.S. |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Consensus approach based on literature | P.D., community partners, A.S., |

| 5. Defining themes | Consensus approach based on emergent themes and the literature | K.M., community partners, A.S. |

| 6. Producing a report | K.M., A.S. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spiropoulos, A.; Desjardine, P.; Adamo, J.; Daya, R.; Zaretsky, L.; Milaney, K. More than Just a Roof: Solutions to Better Support Families from Homelessness to Healing. Societies 2025, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040094

Spiropoulos A, Desjardine P, Adamo J, Daya R, Zaretsky L, Milaney K. More than Just a Roof: Solutions to Better Support Families from Homelessness to Healing. Societies. 2025; 15(4):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040094

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpiropoulos, Athina, Patricia Desjardine, Jocelyn Adamo, Rukhsaar Daya, Lisa Zaretsky, and Katrina Milaney. 2025. "More than Just a Roof: Solutions to Better Support Families from Homelessness to Healing" Societies 15, no. 4: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040094

APA StyleSpiropoulos, A., Desjardine, P., Adamo, J., Daya, R., Zaretsky, L., & Milaney, K. (2025). More than Just a Roof: Solutions to Better Support Families from Homelessness to Healing. Societies, 15(4), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040094