The Labor Market Challenges and Coping Strategies of Highly Skilled Second-Generation Immigrants in Europe: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

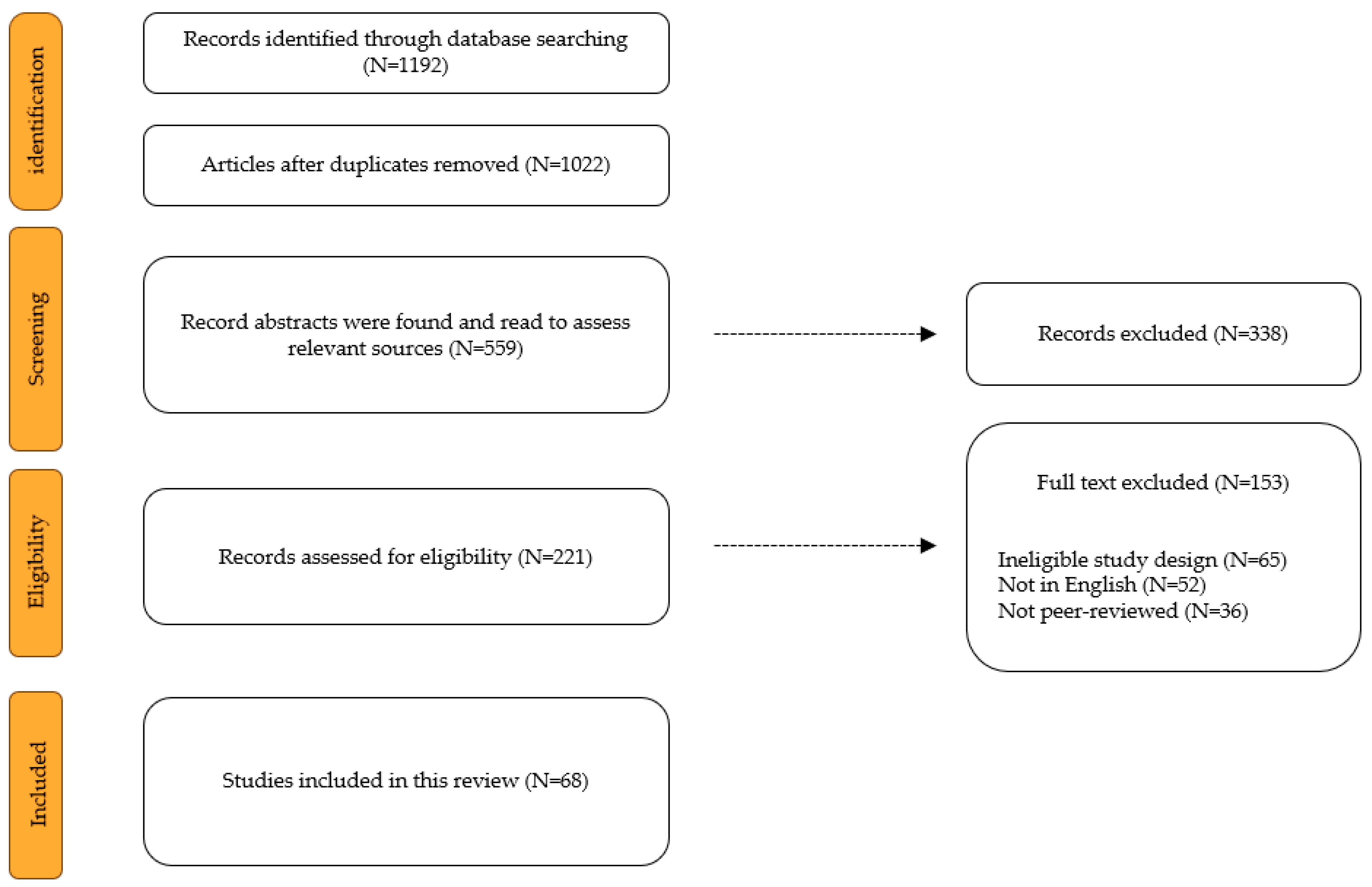

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Labor Market Challenges

4.2. Organizational Practice

4.3. Discrimination and Perceived Discrimination

The Integration Paradox

4.4. Stigmatization and Belonging in High Professional and Social Spheres

4.5. Coping Strategies

4.5.1. Ethnic Niches and Entrepreneurship

4.5.2. Transnational Mobility

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Conclusion and Further Research Opportunities

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alba, R. Bright vs. blurred boundaries: Second-generation assimilation and exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2005, 28, 20–49. [Google Scholar]

- Drouhot, L.G.; Nee, V. Assimilation and the second generation in Europe and America: Blending and segregating social dynamics between immigrants and natives. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2019, 45, 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Crul, M.; Zhou, M.; Lee, J.; Schnell, P.; Keskiner, E. Success against all odds. In The Changing Face of World Cities: Young Adult Children of Immigrants in Europe and the United States; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Foreign-Born People and Their Descendants—Main Characteristics. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Foreign-born_people_and_their_descendants_-_main_characteristics (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Second Generation Immigrants in the EU Generally Well Integrated into the Labour Market. Eurostat Press Office. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7724025/3-28102016-BP-EN.pdf/6e144b14-d5e1-499e-a271-2d70a10ed6fe (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Midtbøen, A.H.; Nadim, M. Ethnic niche formation at the top? Second-generation immigrants in Norwegian high-status occupations. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 42, 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Midtbøen, A.H.; Nadim, M. Becoming elite in an egalitarian context: Pathways to law and medicine among Norway’s second-generation. In New Social Mobility: Second Generation Pioneers in Europe; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Abramitzky, R.; Boustan, L.; Jácome, E.; Pérez, S. Intergenerational mobility of immigrants in the United States over two centuries. Am. Econ. Rev. 2021, 111, 580–608. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz, P.; Mollenkopf, J.H.; Waters, M.C.; Holdaway, J. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Engzell, P.; Ichou, M. Status loss: The burden of positively selected immigrants. Int. Migr. Rev. 2020, 54, 471–495. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, C.; Lanuza, Y.R. An immigrant paradox? Contextual attainment and intergenerational educational mobility. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 82, 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- Drouhot, L.G. Fitting in at the top? Stigma and the negotiation of belonging among the new immigrant elite in France. Int. Migr. Rev. 2024, 58, 1434–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Waldring, I.; Crul, M.; Ghorashi, H. Discrimination of second-generation professionals in leadership positions. Soc. Incl. 2015, 3, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio, V.; Lancee, B.; Veit, S.; Yemane, R. Muslim by default or religious discrimination? Results from a cross-national field experiment on hiring discrimination. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 1305–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, N.; Johnston, R. Ethno-religious identities and persisting penalties in the UK labor market. Soc. Sci. J. 2015, 52, 490–502. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, M. Religious diversity, Islam, and integration in Western Europe—Dissecting symbolic, social, and institutional boundary dynamics. KZfSS Kölner Z. Soziologie Sozialpsychologie 2023, 75 (Suppl. S1), 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Europe’s Growing Muslim Population. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Alba, R.D.; Nee, V. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schachter, A. From “different” to “similar”: An experimental approach to understanding assimilation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 81, 981–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Alloul, J. Leaving Europe, aspiring access: Racial capital and its spatial discontents among the Euro-Maghrebi minority. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2020, 18, 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, O. France, you love it but leave it: The silent flight of French Muslims. Mod. Contemp. Fr. 2023, 31, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, M.; Kas, J. The integration paradox: A review and meta-analysis of the complex relationship between integration and reports of discrimination. Int. Migr. Rev. 2024, 58, 1384–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Quillian, L.; Heath, A.; Pager, D.; Midtbøen, A.H.; Fleischmann, F.; Hexel, O. Do some countries discriminate more than others? Evidence from 97 field experiments of racial discrimination in hiring. Sociol. Sci. 2019, 6, 467–496. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, J. Boundaries of Frenchness: Cultural citizenship and France’s middle-class North African second-generation. Identities 2015, 22, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, J. Citizen Outsider: Children of North African Immigrants in France; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ashourizadeh, S.; Saeedikiya, M.; Aeeni, Z.; Poorhosseinzadeh, M. Human capital and entrepreneurial career choices of immigrants originating from emerging economies: The liability of foreignness perspective. In International Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrokni, S. The transnational career aspirations of France’s high-achieving second-generation Maghrebi migrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 437–454. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrokni, S. The minority culture of mobility of France’s upwardly mobile descendants of North African immigrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2015, 38, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, M.; Welburn, J.S.; Fleming, C.M. Responses to discrimination and social resilience under neoliberalism: The United States compared. In New Perspectives on Resilience in Socio-Economic Spheres; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 143–176. [Google Scholar]

- Erel, U.; Murji, K.; Nahaboo, Z. Understanding the contemporary race–migration nexus. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2016, 39, 1339–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann, J.P. The paradox of integration: Why do higher educated new immigrants perceive more discrimination in Germany? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1377–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, M.; Schneider, J.; Keskiner, E.; Lelie, F. The multiplier effect: How the accumulation of cultural and social capital explains steep upward social mobility of children of low-educated immigrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2017, 40, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskiner, E.; Crul, M. How to reach the top? Fields, forms of capital, and strategies in accessing leadership positions in France among descendants of migrants from Turkey. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2017, 40, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arrighetti, A.; Bolzani, D.; Lasagni, A. Beyond the enclave? Break-outs into mainstream markets and multicultural hybridism in ethnic firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, M. The salience of ethnic identity in entrepreneurship: An ethnic strategies of business action framework. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldinger, R. The making of an immigrant niche. Int. Migr. Rev. 1994, 28, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, M.; Briscoe, F.; Fernandez-Mateo, I.; Sterling, A. The employment relationship and inequality: How and why changes in employment practices are reshaping rewards in organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 61–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurison, D.; Friedman, S. The Class Ceiling in the United States: Class-Origin Pay Penalties in Higher Professional and Managerial Occupations. Soc. Forces 2024, 103, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, L.A. Hiring as cultural matching: The case of elite professional service firms. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 999–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, L.A.; Tilcsik, A. Class advantage, commitment penalty: The gendered effect of social class signals in an elite labor market. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 81, 1097–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft, K.L. The glass slipper: “Incorporating” occupational identity in management studies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.K.; Anteby, M. Task segregation as a mechanism for within-job inequality: Women and men of the Transportation Security Administration. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 61, 184–216. [Google Scholar]

- Drange, I.; Helland, H. The sheltering effect of occupational closure? Consequences for ethnic minorities’ earnings. Work Occup. 2019, 46, 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Keskiner, E.; Lang, C.; Konyali, A.; Rezai, S. Becoming successful in the business and law sectors: Institutional structures and individual resources. In New Social Mobility: Second Generation Pioneers in Europe; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C.; Pott, A.; Schneider, J. Context matters: The varying roles of social ties for professional careers of immigrants’ descendants. In Revisiting Migrant Networks: Migrants and Their Descendants in Labour Markets; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Konyali, A. Turning disadvantage into advantage: Achievement narratives of descendants of migrants from Turkey in the corporate business sector. New Divers. 2014, 16, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Leuven, E.; Oosterbeek, H. Overeducation and mismatch in the labor market. In Handbook of the Economics of Education; Hanushek, E., Machin, S., Woessma, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 283–326. [Google Scholar]

- Åslund, O.; Hensvik, L.; Skans, O.N. Seeking similarity: How immigrants and natives manage in the labor market. J. Labor Econ. 2014, 32, 405–441. [Google Scholar]

- Lippens, L.; Vermeiren, S.; Baert, S. The state of hiring discrimination: A meta-analysis of (almost) all recent correspondence experiments. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2023, 151, 104315. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.P.; King, E.B.; Nelson, J.; Geller, D.S.; Bowes-Sperry, L. Beyond the business case: An ethical perspective of diversity training. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J. Information and Economic Behavior (No. TR-14); Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Baert, S.; Albanese, A.; du Gardein, S.; Ovaere, J.; Stappers, J. Does work experience mitigate discrimination? Econ. Lett. 2017, 155, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen, L.; Lancee, B.; Veit, S.; Yemane, R. Discrimination against Turkish minorities in Germany and the Netherlands: Field experimental evidence on the effect of diagnostic information on labour market outcomes. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann, B.; Busch-Heizmann, A.; Holst, E. Immigrant occupational composition and the earnings of immigrants and natives in Germany: Sorting or devaluation? Int. Migr. Rev. 2017, 51, 475–505. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaskovic-Devey, D.; Lin, K.H.; Meyers, N. Did financialization reduce economic growth? Socio-Econ. Rev. 2015, 13, 525–548. [Google Scholar]

- Waldring, I. The Fine Art of Boundary Sensitivity: Second-Generation Professionals Engaging with Social Boundaries in the Workplace. Ph.D. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018. Available online: https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/the-fine-art-of-boundary-sensitivity-second-generation-profession (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Small, M.L.; Pager, D. Sociological perspectives on racial discrimination. J. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 34, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Madera, J.M.; King, E.B.; Hebl, M.R. Bringing social identity to work: The influence of manifestation and suppression on perceived discrimination, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2012, 18, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Stamarski, C.S.; Son Hing, L.S. Gender inequalities in the workplace: The effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1400. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, N.; Davids, T.; Spierings, N. The lived experience of an integration paradox: Why high-skilled migrants from Turkey experience little national belonging in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansen, A.S.; Penner, A.; Elvira, M.; Godechot, O.; Hällsten, M.; Henriksen, L.F.; Hou, F.; Lippényi, Z.; Petersen, T.; Reichelt, M.; et al. Immigrant–Native Pay Gap Driven by Lack of Access to High-Paying Jobs. 2023. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/2p4vw_v3 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Han, J.; Hermansen, A.S. Wage disparities across immigrant generations: Education, segregation, or unequal pay? ILR Rev. 2024, 77, 598–625. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, F.; Lee, D.S.; Lemieux, T. Growing income inequality in the United States and other advanced economies. J. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 34, 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yanasmayan, Z. Does education ‘trump’ nationality? Boundary-drawing practices among highly educated migrants from Turkey. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2016, 39, 2041–2059. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste; Nice, R., Ed. and Translator; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz, P.; Waters, M.C. Becoming white or becoming mainstream? Defining the endpoint of assimilation. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hass, B.S.; Lutek, H. The Dutch inside the ‘Moslima’and the ‘Moslima’inside the Dutch: Processing the religious experience of Muslim women in the Netherlands. Societies 2018, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statham, P.; Foner, N. (Eds.) Introduction: Assimilation and integration in the twenty-first century: Where have we been and where are we going? In Re-Thinking Assimilation and Integration; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E. Ethnic Enclaves and Niches: Theory. In The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration; Ness, I., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 1337–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chen, H.S. Perspectives on Necessity-Driven Immigrant Entrepreneurship: Interactions with Entrepreneurial Ecosystems through the Lens of Dynamic Capabilities. Societies 2024, 14, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldinger, R. From Ellis Island to LAX: Immigrant prospects in the American city. Int. Migr. Rev. 1996, 30, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, W.P.; Luo, X. Internationalization and the performance of born-global SMEs: The mediating role of social networks. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Alloul, J. ‘Traveling habitus’ and the new anthropology of class: Proposing a transitive tool for analyzing social mobility in global migration. Mobilities 2021, 16, 178–193. [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger, R. Immigrant transnationalism. Curr. Sociol. 2013, 61, 756–777. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, J.; Kelly, M.; Van Liempt, I. Free movement? The onward migration of EU citizens born in Somalia, Iran, and Nigeria. Popul. Space Place 2016, 22, 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Della Puppa, F.; King, R. The new ‘twice migrants’: Motivations, experiences and disillusionments of Italian-Bangladeshis relocating to London. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1936–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli, E. Entre ici et là-bas: Les Parcours D’entrepreneurs Transnationaux. Investissement Economique en Algerie des Descendants de L’immigration Algerienne de France. Sociologie 2010, 1, 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- Bereni, L. “Why not a blonde woman?” Identity realism and diversity work in New York and in Paris. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2024, 47, 1964–1986. [Google Scholar]

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Second-generation immigrants High-skilled second generation | Refugees, asylum-seekers, non-skilled second-generation immigrants, first-generation immigrants |

| Concept | Organizational practices, discrimination, belonging, ethnic niches, entrepreneurship, and geographic mobility | N/A |

| Context | Europe | N/A 1 |

| Study Design | Empirical study published in a peer-reviewed journal | Commentaries, editorials, opinion pieces, and non-peer reviewed articles |

| Language | Studies published in English-language | N/A |

| Date of Publication | 2010–2024 | N/A 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Achouche, N. The Labor Market Challenges and Coping Strategies of Highly Skilled Second-Generation Immigrants in Europe: A Scoping Review. Societies 2025, 15, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040093

Achouche N. The Labor Market Challenges and Coping Strategies of Highly Skilled Second-Generation Immigrants in Europe: A Scoping Review. Societies. 2025; 15(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleAchouche, Noa. 2025. "The Labor Market Challenges and Coping Strategies of Highly Skilled Second-Generation Immigrants in Europe: A Scoping Review" Societies 15, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040093

APA StyleAchouche, N. (2025). The Labor Market Challenges and Coping Strategies of Highly Skilled Second-Generation Immigrants in Europe: A Scoping Review. Societies, 15(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040093