A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Explore Determinants of Catastrophic Healthcare Expenses

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To discover the key issues that influence the CHCE of rural households

- To examine the causal relationships among various determinants of the CHCE

- To develop a holistic MCDA framework for comparative evaluation and examining hierarchical relationships

- This study offers a detailed framework for comprehending CHCE in vulnerable groups. It examines numerous determinants, including socioeconomic status, education, employment stability, and demographic characteristics, by integrating expert and household viewpoints.

- The methodology of this paper enhances current theories by elucidating the complex interconnections among financial, institutional, and demographic variables influencing CHCE, thereby advancing the discipline of health economics and management.

- The study utilizes the FullEX methodology to ascertain stakeholder priorities, facilitating a transparent evaluation of the intricate elements influencing CHCE. Furthermore, ISM and MICMAC analyses elucidate hierarchical and causal linkages among critical determinants, thereby providing a comprehensive basis for decision-making.

- The report functions as an evidence-based scientific approach for industry and government leaders to enhance health financing and to ensure social safety in resource-constrained environments. This, in turn, helps formulate inclusive policies for sustainable development.

- This paper incorporates the concept of reliability index and uses the integration and adjustment coefficients. The extended FullEX method allows more flexibility in decision-making.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Determinants of Health (SDH)

2.2. Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Service (ABMHS)

2.3. Health Financing Equity Framework (HFE)

2.4. Related Studies

2.5. Research Gaps

- (a)

- Prior studies primarily rely on regression analysis, decomposition techniques, or descriptive statistics to identify the drivers of CHCE. While effective for quantifying associations, these methods fail to assess the relative impacts of the components. Advanced MCDA frameworks, such as FullEX help comprehensive prioritization and structural understanding of the determinants.

- (b)

- The determinants are complex and interlinked. However, the literature review reveals a lack of understanding of their interrelations and causal connections. It recommends employing ISM-MICMAC methodologies to discern these connections and focus on primary and secondary determinants for efficient policy intervention.

- (c)

- No prior study has used multiple theories to determine the influencing factors of CHCE comprehensively. The current research draws on three relevant theories. Furthermore, no previous research has considered a combination of responses obtained from experts and households.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Determinants

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Methodology

- (a)

- Obtain the difference between the maximum and minimum values for each determinant in the weighted NIRM as follows.

- (b)

- The weights of the determinants are recalculated as follows.

- (c)

- Calculate the RI as demonstrated below.

- If a cell (i, j) contains “V”, the assigned value is “1” and the corresponding (j, i) cell is assigned with “0”.

- If a cell (i, j) contains “A”, the assigned value is “0” and the corresponding (j, i) cell is assigned with “1”.

- If a cell (i, j) contains “X”, the assigned value is “1” and the corresponding (j, i) cell is assigned with “1”.

- If a cell (i, j) contains “O”, the assigned value is “0” and the corresponding (j, i) cell is assigned with “0”.

4. Findings

4.1. Stage 1: Identification of Key Determinants Utilizing the FullEx Method

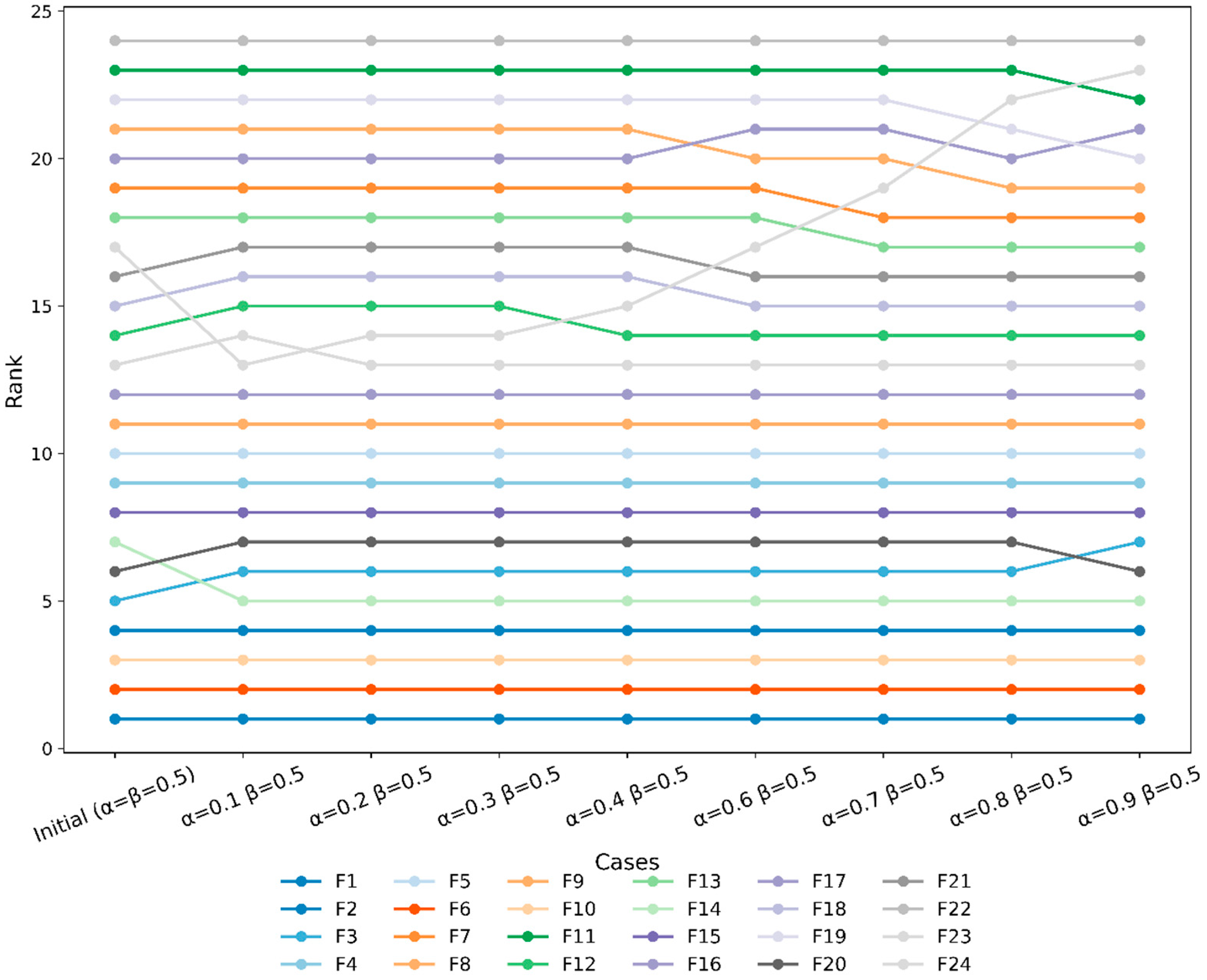

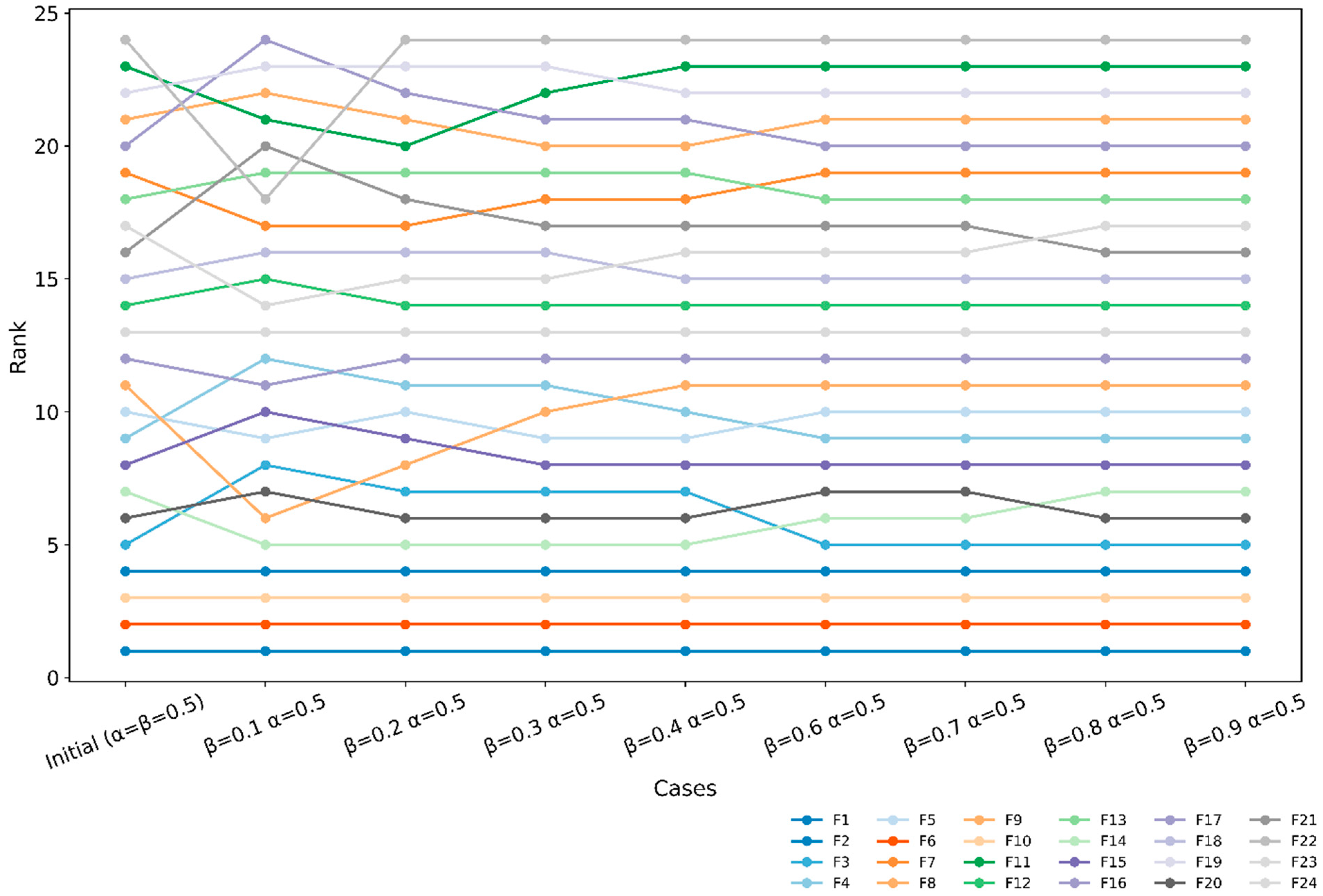

4.1.1. Validation of Results

4.1.2. Sensitivity Analysis

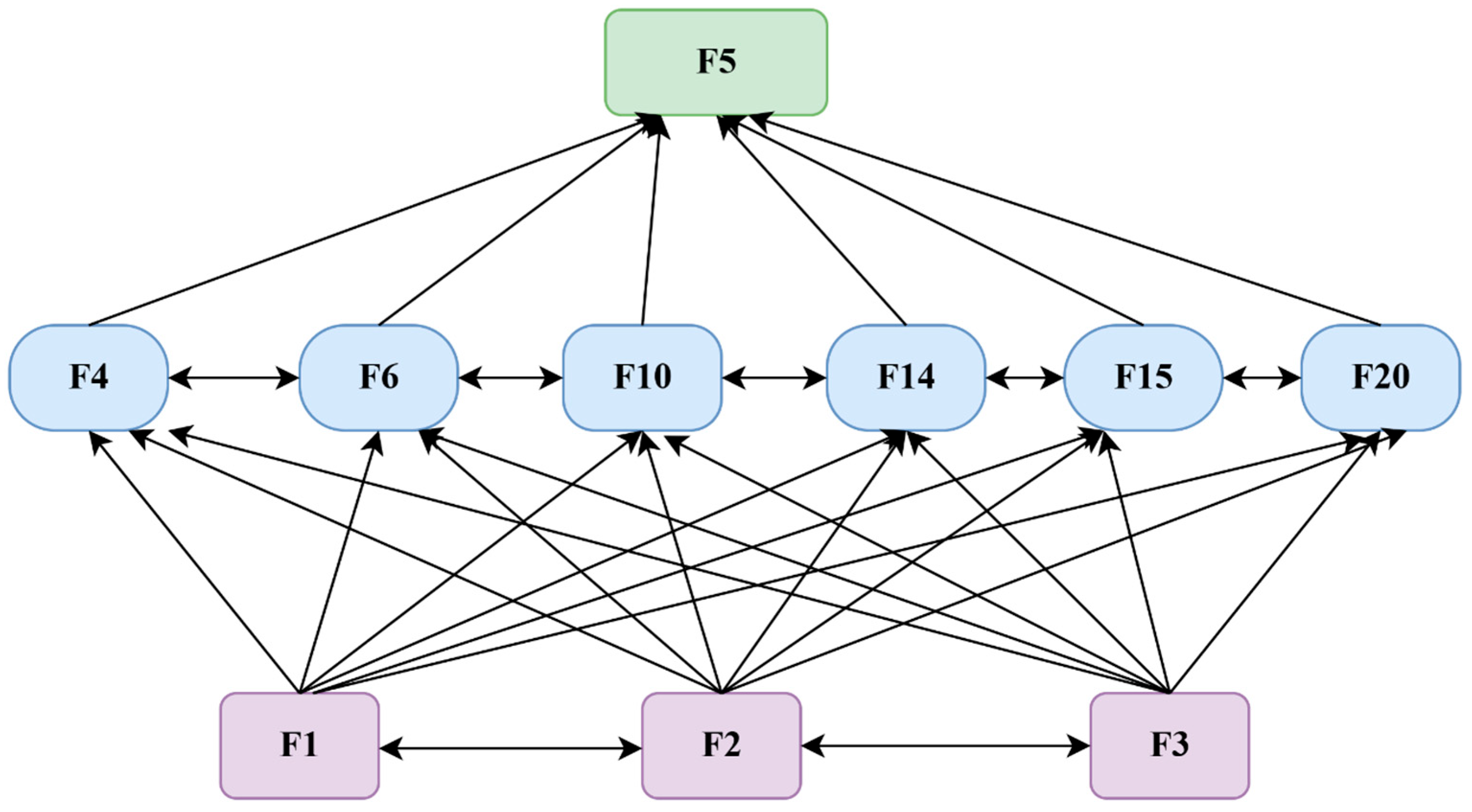

4.2. Stage 2: Identification of the Causal Relationships Among Key Determinants (ISM-MICMAC)

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Implications

- The MCDA findings assist healthcare administrators in prioritizing resource allocation and interventions by identifying critical characteristics such as low household income and elevated birth rates that impact child health. Managers need to concentrate on specific financial and wellness initiatives for at-risk populations. Furthermore, by comprehending linking characteristics such as insufficient governance, hospital administrators and insurers can formulate policies that enhance service delivery. This necessitates the inclusion of socioeconomic factors in health spending models to improve forecasts and deliver customized treatments.

- The study highlights the need to control inequities and social vulnerabilities that render households susceptible to financial shocks from healthcare expenses. It recognizes insufficient education and rural economic disparities as critical determinants for community-oriented programs to improve health literacy and economic empowerment for at-risk communities. The interconnections among these factors indicate that social policies should employ comprehensive, multi-sectoral strategies that address education, employment, and healthcare access. The findings support cross-sector collaborations among healthcare providers, local governments, and social organizations to create social safety nets and empower disadvantaged populations against catastrophic costs.

- The findings provide insights for public health policy formulation by classifying determinants into driving, connecting, and dependent elements, facilitating strategic interventions. It urges governments to expand risk pooling, enhance transparency in governance, and optimize referral networks to assist disadvantaged households. The results align with global standards that promote integrated systems for social protection, rural development, and healthcare reform.

- The study emphasizes the scientific usefulness of MCDA-based approaches in healthcare decision-making, offering a framework relevant to diverse policy matters. Using ISM-MICMAC analysis, it assesses interdependencies among variables and enhances decision transparency. The MCDA methodology enhances flexible modeling, hence advancing health economics and policy approaches. This comprehensive framework helps mitigate exorbitant healthcare costs, enabling systematic, sustainable actions across the healthcare system [75,76] (Marsh et al., 2017; Gongora-Salazar et al., 2023)

5.2. Future Scopes

- The success of the FullEX method largely depends on experts’ evaluations and context. Future studies may conduct a large-scale empirical analysis (through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis) to validate the findings.

- The current work was focused on the rural segment. However, future studies may consider regional comparisons to examine the common factors and heterogeneous requirements.

- Future studies may be designed to examine the intermediate role of NGOs in implementing appropriate measures to reduce CHCE. A mediation model can be built and tested. In this regard, the pivotal role of technology in mitigating CHCE can also be examined.

- Future studies may investigate the efficacy of the government schemes and initiatives in removing the OOP financial burden of the people. In this context, the usefulness of the PPP models may be examined.

- Cross-cultural applications and comparative analysis may yield significant insights into the adaptability of MCDA approaches. Furthermore, integrating MCDA findings with qualitative and political analyses will provide a solid basis for policy and administrative decisions.

- The FullEX model may be further extended using various uncertainty measures (using fuzzy and rough numbers) to offset the subjective bias and improve its robustness.

- The current study involves a limited number of experts having 20+ years of experience. Although several studies on MCDM applications (e.g., [79] Guan et al., 2024) have considered 5 years of experience as a benchmark, we recognize this as a limitation of our work. Nevertheless, the current work draws on the opinions of a large group of residents and experts. Thus, this limitation does not undermine the usefulness and reliability of the current work. Future studies can validate the findings of this work by considering more experts having 20–25 years of experience.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Expert | Qualification | Rating | Weight (Qual) | Experience (Years) | Rating | Weight (Exp) | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 2 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0433 |

| Expert 3 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 4 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 5 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | Less than 5 | 1 | 0.0130 | 0.0184 |

| Expert 6 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0314 |

| Expert 7 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 8 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 9 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0433 |

| Expert 10 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 11 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 12 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 13 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 14 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0433 |

| Expert 15 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | Less than 5 | 1 | 0.0130 | 0.0184 |

| Expert 16 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 17 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0314 |

| Expert 18 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | Less than 5 | 1 | 0.0130 | 0.0184 |

| Expert 19 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 20 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 21 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 22 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | Less than 5 | 1 | 0.0130 | 0.0184 |

| Expert 23 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | Less than 5 | 1 | 0.0130 | 0.0184 |

| Expert 24 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0433 |

| Expert 25 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 26 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | More than 15 | 4 | 0.0519 | 0.0498 |

| Expert 27 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 28 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 6 to 10 | 2 | 0.0260 | 0.0249 |

| Expert 29 | Ph.D. | 2 | 0.0476 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0433 |

| Expert 30 | Masters | 1 | 0.0238 | 10 to 15 | 3 | 0.0390 | 0.0314 |

| Ranks | Weights | Final | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/L | Determinants of Catastrophic Health Expenditure | Experts | Household | Experts | Household | Weight | Rank |

| F1 | Low household income level | 1 | 1 | 0.0534 | 0.0436 | 0.0485 | 1 |

| F2 | Lack of job security | 4 | 4 | 0.0480 | 0.0428 | 0.0454 | 4 |

| F3 | Low education level | 5 | 11 | 0.0457 | 0.0417 | 0.0437 | 6 |

| F4 | Lack of assets and financial resilience | 9 | 15 | 0.0445 | 0.0413 | 0.0429 | 9 |

| F5 | Disparity in rural economic conditions | 10 | 8 | 0.0439 | 0.0419 | 0.0429 | 10 |

| F6 | Presence of dependent households | 2 | 2 | 0.0520 | 0.0436 | 0.0478 | 2 |

| F7 | Composition and size of households | 19 | 18 | 0.0366 | 0.0411 | 0.0388 | 19 |

| F8 | History of chronic illness and comorbidity | 21 | 23 | 0.0364 | 0.0403 | 0.0384 | 20 |

| F9 | Presence of elderly people in the family | 11 | 5 | 0.0418 | 0.0427 | 0.0423 | 11 |

| F10 | Frequent birth rate and child health vulnerability | 3 | 3 | 0.0500 | 0.0433 | 0.0467 | 3 |

| F11 | Long-term disability | 23 | 20 | 0.0355 | 0.0406 | 0.0380 | 23 |

| F12 | Limited public health infrastructure | 14 | 14 | 0.0391 | 0.0414 | 0.0402 | 14 |

| F13 | Costly diagnostic and treatment services | 18 | 19 | 0.0371 | 0.0406 | 0.0389 | 18 |

| F14 | Absence of prepayment or risk-pooling mechanisms | 7 | 6 | 0.0451 | 0.0425 | 0.0438 | 5 |

| F15 | Ineffective referral system in healthcare facilities | 8 | 10 | 0.0448 | 0.0418 | 0.0433 | 8 |

| F16 | Poor quality of public services | 12 | 9 | 0.0416 | 0.0419 | 0.0418 | 12 |

| F17 | Hidden costs in public facilities | 20 | 24 | 0.0365 | 0.0402 | 0.0384 | 21 |

| F18 | Ineffective and inadequate public insurance | 15 | 17 | 0.0385 | 0.0411 | 0.0398 | 15 |

| F19 | Ineffective resource allocation | 22 | 22 | 0.0359 | 0.0403 | 0.0381 | 22 |

| F20 | Ineffective health governance and accountability measures | 6 | 7 | 0.0452 | 0.0422 | 0.0437 | 7 |

| F21 | Lack of robust regulation for the private healthcare sector | 16 | 21 | 0.0380 | 0.0405 | 0.0393 | 17 |

| F22 | Poor health-seeking behavior and delay in care | 24 | 16 | 0.0311 | 0.0413 | 0.0362 | 24 |

| F23 | Lack of trust in public services | 13 | 13 | 0.0415 | 0.0415 | 0.0415 | 13 |

| F24 | Gender disparity in decision-making | 17 | 12 | 0.0377 | 0.0415 | 0.0396 | 16 |

References

- Ssewanyana, S.; Kasirye, I. Estimating Catastrophic Health Expenditures from Household Surveys: Evidence from Living Standard Measurement Surveys (LSMS)-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (ISA) From Sub-Saharan Africa. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2020, 18, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Atun, R.; Oldenburg, B.; McPake, B.; Tang, S.; Mercer, S.W.; Cowling, T.E.; Sum, G.; Qin, V.M.; Lee, J.T. Physical Multimorbidity, Health Service Use, and Catastrophic Health Expenditure by Socioeconomic Groups in China: An Analysis of Population-Based Panel Data. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e840–e849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, H.C. Exploring Dynamics in Catastrophic Health Care Expenditure in Nigeria. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yao, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, T.; Liu, M.; Gong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ye, C. How Do Intergenerational Economic Support, Emotional Support and Multimorbidity Affect the Catastrophic Health Expenditures of Middle-Aged and Elderly Families?–Evidence From CHARLS2018. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 872974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Gautam, S.; Yadav, G.K.; Niraula, S.R.; Singh, S.B.; Rai, R.; Poudel, S.; Sah, R.B. Catastrophic Health Expenditure on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases Among Elder Population: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Sub-Metropolitan City of Eastern Nepal. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, P.O.; Ibirongbe, D.O.; Ipinnimo, T.M.; Solomon, O.O.; Ibikunle, A.I.; Obiagwu, A.E. The Prevalence of Household Catastrophic Health Expenditure in Nigeria: A Rural-Urban Comparison. J. Health Med. Sci. 2021, 4, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefa, M.B.; Woldehanna, B.T.; Mebratie, A.D. Effect of Community-Based Health Insurance on Catastrophic Health Expenditure Among Chronic Disease Patients in Asella Referral Hospital, Southeast Ethiopia: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, S.; Yuan, S.; Dong, Q. The impact of health insurance on poverty among rural older adults: An evidence from nine counties of western China. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazungu, J.; Meyer, C.L.; Sargsyan, K.G.; Qaiser, S.; Chukwuma, A. The Burden of Catastrophic and Impoverishing Health Expenditure in Armenia: An Analysis of Integrated Living Conditions Surveys, 2014–2018. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Singh, A.; Verma, A.; Naranje, K.; Gupta, G. Financial Implications for Families of Newborns Admitted in a Tertiary Care Neonatal Unit in Northern India. J. Neonatol. 2023, 38, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M.; Sharma, R. Financial Burden of Seeking Diabetes Mellitus Care in India: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Sample Survey. Health Care Sci. 2023, 2, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, T.K.S.L.; Jayaseelan, V.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Sakthivel, M.; Majella, M.G. Patient’s Experiences and Satisfaction in Diabetes Care and Out-of-Pocket Expenditure for Follow-Up Care Among Diabetes Patients in Urban Puducherry, South India. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Goli, S. Informal Employment and High Burden of Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Payments Among Older Workers: Evidence from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India. Health Policy Plan. 2024, 40, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Mohanty, P.C. Incidence and Intensity of Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Impoverishment Among the Elderly: An Empirical Evidence from India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, T.; Das, A.; Dawad, S.; Dalal, K. Non-Utilization of Public Healthcare Facilities During Sickness: A National Study in India. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; Siddhanta, A.; Singh, A.; Prinja, S.; Sharma, A.; Sikka, H.; Goswami, L. Potential Impact of the Insurance on Catastrophic Health Expenditures Among the Urban Poor Population in India. J. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Bebarta, K.K.; Tripathi, N. Household Expenditure on Non-COVID Hospitalisation Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Role of Financial Protection Policies in India. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Majumder, S.; Dawn, S.K. Comparing the socioeconomic development of G7 and BRICS countries and resilience to COVID-19: An entropy–MARCOS framework. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2022, 10, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blebu, B.; Liu, P.Y.; Harrington, M.; Nicholas, W.; Jackson, A.; Saleeby, E. Implementation of Cross-Sector Partnerships: A Description of Implementation Factors Related to Addressing Social Determinants to Reduce Racial Disparities in Adverse Birth Outcomes. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudon, C.; Dumont-Samson, O.; Breton, M.; Bourgueil, Y.; Cohidon, C.; Falcoff, H.; Senn, N.; Durme, T.; Van Angrignon-Girouard, É.; Ouadfel, S. How to Better Integrate Social Determinants of Health into Primary Healthcare: Various Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Hamity, C.; Sharp, A.L.; Jackson, A.; Schickedanz, A. Patients’ Attitudes and Perceptions Regarding Social Needs Screening and Navigation: Multi-Site Survey in a Large Integrated Health System. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, A.; Haintz, G.L.; McKenzie, H.; Graham, M. Influences on Reproductive Decision-Making Among Forcibly Displaced Women Resettling in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Callender, C.; Velazquez, D.; Adera, M.; Dave, J.M.; Olvera, N.; Chen, T.-A.; Goldsworthy, N. Perspectives of Black/African American and Hispanic Parents and Children Living in Under-Resourced Communities Regarding Factors That Influence Food Choices and Decisions: A Qualitative Investigation. Children 2021, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, G.S.B.; Herkrath, F.J.; Parente, R.C.P.; Pinheiro, R.D.D.S.; Vettore, M.V. Barriers and facilitators to accessing healthcare services among elderly people living in a rural Amazonian community, Brazil. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Fattah, R.A.; Susilo, D.; Satrya, A.; Haemmerli, M.; Kosen, S.; Novitasari, D.; Puteri, G.C.; Adawiyah, E.; Hayen, A.; et al. Determinants of healthcare utilization under the Indonesian national health insurance system–a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, M.; Kasemi, N. Why do older adults choose private healthcare services? Evidence from an urban context in India using Andersen’s Behavioral Model. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. Plus 2025, 2, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, D.; Matschinger, H.; Müller, H.; Saum, K.U.; Quinzler, R.; Haefeli, W.E.; Wild, B.; Lehnert, T.; Brenner, H.; König, H.H. Health care costs in the elderly in Germany: An analysis applying Andersen’s behavioral model of health care utilization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitsch, B.; Gohl, D.; Von Lengerke, T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2012, 9, Doc11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R. Adopting Andersen’s behavior model to identify factors influencing maternal healthcare service utilization in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Yan, S.; Ma, M.; Tarimo, C.S.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Y.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Ye, B. Factors influencing health service utilization among 19,869 China’s migrant population: An empirical study based on the Andersen behavioral model. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1456839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Van Doorslaer, E. Equity in health care finance and delivery. In Handbook of Health Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 1803–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Bakhat, M.; Boudhar, A. The incidence of catastrophic and impoverishing health spending in Morocco: The value added of new methodologies. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2025, 25, 337–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodniak, N.; Gharpure, R.; Feng, L.; Lai, X.; Fang, H.; Tian, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, G.; Salcedo-Mejía, F.; Alvis-Zakzuk, N.J.; et al. Costs of Influenza Illness and Acute Respiratory Infections by Household Income Level: Catastrophic Health Expenditures and Implications for Health Equity. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2025, 19, e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.A.R.; Jalal, M.J.E.; Ding, S.; Begum, I.A.; Yang, B.; Alam, M.J. Determinants of Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Its Impact on Poverty in Deltaic Country: Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 5414–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Gasbarro, D.; Alam, K.; Alam, K. Rural-urban disparities in household catastrophic health expenditure in Bangladesh: A multivariate decomposition analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.O.; Adeniran, A.; Aderibigbe, A.; Akinyemi, O.; Fagbemi, T.; Ayodeji, O.; Adepase, B.; Zamba, E.; Abdurrazzaq, H.; Oniyire, F.; et al. Factors associated with Catastrophic Healthcare Expenditure in communities of Lagos Nigeria: A Megacity experience. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enemuwe, I.M.; Oyibo, P. Prevalence and predictors of catastrophic health expenditure due to out-of-pocket payment among rural households in Delta State, Nigeria: A community-based cross-sectional study. Discov. Health Syst. 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enuagwuna, F.C.; Ogaji, D.S.; Tebu, O. Risk and determinants of catastrophic health expenditure among rural households in rivers state. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2024, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinuka, L.; Mwemutsi, F.A. Magnitude and determinants of the catastrophic out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in rural and urban areas: Lessons from Tanzania panel data survey. Discov. Health Syst. 2024, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadiwos, Y.B.; Kassahun, M.M.; Mebratie, A.D. Catastrophic and impoverishing out-of-pocket health expenditure in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Ethiopia socioeconomic survey. Health Econ. Rev. 2025, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matebie, G.Y.; Mebratie, A.D.; Demeke, T.; Afework, B.; Kantelhardt, E.J.; Addissie, A. Catastrophic health expenditure and associated factors among hospitalized cancer patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2024, 17, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansra, P.; Oberoi, S.; Garg, A. Out-of-pocket payments catastrophic healthcare expenditure for non-communicable diseases: Results of a State-wide STEPS survey in north India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2025, 161, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, S.; Verma, V.R.; Gollapalli, P.K.; Albadrani, M. Decomposing the inequalities in the catastrophic health expenditures on the hospitalization in India: Empirical evidence from national sample survey data. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1329447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, H.S.; Rout, H.S.; Jakovljevic, M. Catastrophic health expenditure of inpatients in emerging economies: Evidence from the Indian subcontinent. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, N.; Bibi, M.; Saba, N.; Arshad, A.; Khan, I.H. Determinants of Health Expenditures: A Case of High Populated Asian Countries. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 2024, 13, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodi, Z.; Moradi, G.; Moradi, Y.; Bolbanabad, A.M.; Hoorsan, H. Assessing Catastrophic Health Expenditure among Iraqi Households: A Cross-Sectional Study. Iran. J. Public Health 2025, 54, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, K.F.; Ahsan, M.N.; Haider, M.Z. Understanding variation in catastrophic health expenditure from socio-ecological aspect: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulupi, S.; Waithera, C.; Tomeny, E.M.; Egere, U.; Meme, H.; Kirubi, B.; Chakaya, J.; Barasa, E.; Taegtmeyer, M.; Wingfield, T. Catastrophic health expenditure, social protection coverage, and financial coping strategies in adults with symptoms of chronic respiratory diseases in Kenya: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e1301–e1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagstaff, A.; Flores, G.; Hsu, J.; Smitz, M.F.; Chepynoga, K.; Buisman, L.R.; van Wilgenburg, K.; Eozenou, P. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e169–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Evans, D.B.; Kawabata, K.; Zeramdini, R.; Klavus, J.; Murray, C.J. Household catastrophic health expenditure: A multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003, 362, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, E.; O’Donnell, O.; Rannan-Eliya, R.P.; Somanathan, A.; Adhikari, S.R.; Garg, C.C.; Harbianto, D.; Herrin, A.N.; Huq, M.N.; Ibragimova, S.; et al. Catastrophic payments for health care in Asia. Health Econ. 2007, 16, 1159–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, P.; Ahuja, R.; Bhandari, L. The impoverishing effect of healthcare payments in India: New methodology and findings. Econ. Political Wkly. 2010, 45, 65–71. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25664359 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Reddy, K.S.; Patel, V.; Jha, P.; Paul, V.K.; Kumar, A.S.; Dandona, L. Towards achievement of universal health care in India by 2020: A call to action. Lancet 2011, 377, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Doorslaer, E.V. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: With applications to Vietnam 1993–1998. Health Econ. 2003, 12, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolongaita, S.; Lee, Y.; Johansson, K.A.; Haaland, Ø.A.; Tolla, M.T.; Lee, J.; Verguet, S. Financial hardship associated with catastrophic out-of-pocket spending tied to primary care services in low-and lower-middle-income countries: Findings from a modeling study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.B.; Keisler, J.; Linkov, I. Multi-criteria decision analysis in environmental sciences: Ten years of applications and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3578–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Du, Y.; Liang, H.; Sun, B. Large Group Decision-Making Approach Based on Stochastic MULTIMOORA: An Application of Doctor Evaluation in Healthcare Service. Complexity 2018, 2018, 5409405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, T. Determination of the relative importance of criteria when the number of people judging is a small sample. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2008, 14, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Pamucar, D. A modified EDAS model for comparison of mobile wallet service providers in India. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bošković, S.; Švadlenka, L.; Jovčić, S.; Dobrodolac, M.; Simic, V.; Bacanin, N. A new FullEX decision-making technique for criteria importance assessment: An application to the sustainable last-mile delivery courier selection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 137426–137436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, S.; Jovčić, S.; Simic, V.; Švadlenka, L.; Dobrodolac, M.; Bacanin, N. A new criteria importance assessment (CIMAS) method in multi-criteria group decision-making: Criteria evaluation for supplier selection. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2025, 23, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. Interpreting the interpretive structural model. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2012, 13, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatwani, G.; Singh, S.P.; Trivedi, A.; Chauhan, A. Fuzzy-TISM: A fuzzy extension of TISM for group decision making. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2015, 16, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Qahmash, A. Smartism: Implementation and assessment of interpretive structural modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almerino, P., Jr.; Sacro, M.; Almerino, J.T.; Esmoso, A.D.; Maturan, F.; Atibing, N.M.; Evangelista, S.S.; Aro, J.L.; Ocampo, L. Interpretive Structural Modelling and MICMAC Analysis for Rethinking Special Mathematics Education. Int. J. Knowl. Syst. Sci. (IJKSS) 2024, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Ren, S.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y. Critical success factors for metaverse implementation in the service industry: A hybrid ISM-DEMATEL approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 87, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkedder, N.; Jain, V.; Salunke, P. Determinants of virtual reality stores influencing purchase intention: An interpretive structural modeling approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Khawash, N.; Chatterjee, P.; Zavadskas, E.K. Preference using Root Value based on Aggregated Normalizations (PROVAN): A Data-Driven Method for Socio-Economic and Innovation Assessment. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2026, 103, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki, M.R.; Biswas, S.; Guha, B.; Pamucar, D.; Bandyopadhyay, G. Introspecting the childhood intrinsic interests of the HR professionals: An intuitionistic fuzzy decision analysis framework. Kybernetes 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Stević, Ž.; Sremac, S. A new model for determining weight coefficients of criteria in MCDM models: Full consistency method (FUCOM). Symmetry 2018, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Biswas, S.; Pamucar, D.; Simic, V. A Novel Intuitionistic Fuzzy based Computing Model for Unravelling Key Attributes of Service Quality for Higher Education Management. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Pamucar, D.; Simic, V. Technology adaptation in sugarcane supply chain based on a novel p, q Quasirung Orthopair Fuzzy decision making framework. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, S.; Švadlenka, L.; Jovčić, S.; Simic, V.; Dobrodolac, M.; Elomiya, A. Sustainable propulsion technology selection in penultimate mile delivery using the FullEX-AROMAN method. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 95, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Goetghebeur, M.; Thokala, P.; Baltussen, R. (Eds.) Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to Support Healthcare Decisions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Gongora-Salazar, P.; Rocks, S.; Fahr, P.; Rivero-Arias, O.; Tsiachristas, A. The use of multicriteria decision analysis to support decision making in healthcare: An updated systematic literature review. Value Health 2023, 26, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIB Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894901®=3&lang=2 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Quintal, C. Evolution of catastrophic health expenditure in a high income country: Incidence versus inequalities. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Bi, W. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach for Equipment Evaluation Based on Cloud Model and VIKOR Method. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/L | Factor | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect: Socioeconomic conditions | |||

| F1 | Low household income level | Low-income households are profoundly affected by even modest health emergencies, resulting in catastrophic expenses. | [34,36,37,49] |

| F2 | Lack of job security | Uncertain employment, without employer-sponsored health insurance, results in higher out-of-pocket expenditures. | [34,38,50] Xu et al., 2003; Sarkar et al., 2025; Enuagwuna et al., 2024 |

| F3 | Low education level | Low educational attainment reduces awareness of health insurance and preventive care, increasing the likelihood of catastrophic health expenditures. | [35,47,51] Van Doorslaer et al., 2007; Mohsin et al., 2024; Rahman et al., 2024 |

| F4 | Lack of assets and financial resilience | Insufficient funds or productive assets restrict the ability to cope during times of illness. | [41,48,52] Berman et al., 2010; Mulupi et al., 2025; Matebie et al., 2024 |

| F5 | Disparity in rural economic conditions | Rural households frequently experience income reductions and elevated indirect costs, thereby heightening their susceptibility to CHCE. | [35,39,49] Wagstaff et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2024; Mwinuka & Mwemutsi, 2024 |

| F6 | Presence of dependent households | The presence of high-dependency individuals (children, the elderly, non-working members) exacerbates the financial strain during illness. | [36,40,50] Xu et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2025; Tadiwos et al., 2025 |

| Aspect: Demographic and health-related issues | |||

| F7 | Composition and size of households | Large families with numerous dependents enhance healthcare expenses. | [37,47,50] Xu et al., 2003; Mohsin et al., 2024; Enemuwe & Oyibo, 2025 |

| F8 | History of chronic illness and comorbidity | Prolonged management of non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) results in persistent out-of-pocket expenditures. | [42,44,51] Van Doorslaer et al., 2007; Kansra et al., 2025; Panda et al., 2024 |

| F9 | Presence of elderly people in the family | Elderly family members necessitate more frequent and expensive healthcare interventions. | [34,41,49] Wagstaff et al., 2018; Sarkar et al., 2025; Matebie et al., 2024 |

| F10 | Frequent birth rate and child health vulnerability | An increasing child birthrate and pediatric illnesses elevate the likelihood of CHCE | [36,47,53] Reddy et al., 2018; Mohsin et al., 2024; Wright et al., 2025 |

| F11 | Long-term disability | Expenditures for the care of disabled members impose a persistent and significant financial strain. | [40,48,52] Berman et al., 2010; Mulupi et al., 2025; Tadiwos et al., 2025 |

| Aspect: Healthcare system-related issues | |||

| F12 | Limited public health infrastructure | Insufficient local facilities compel patients to seek costly private providers. | [34,38,53] Reddy et al., 2018; Sarkar et al., 2025; Enuagwuna et al., 2024 |

| F13 | Costly diagnostic and treatment services | Out-of-pocket expenditures on necessary medications and diagnostics significantly contribute to CHCE. | [42,44,52] Wagstaff et al., 2018; Panda et al., 2024; Kansra et al., 2025 |

| F14 | Absence of prepayment or risk-pooling mechanisms | The lack of appropriate insurance or community-based funding exacerbates unplanned out-of-pocket expenditures. | [47,48,50] Xu et al., 2003; Mohsin et al., 2024; Mulupi et al., 2025 |

| F15 | Ineffective referral system in healthcare facilities | Patients frequently circumvent referral systems, resulting in worse primary care, longer wait times, and financial difficulties stemming from insufficient communication, rural–urban disparities, administrative barriers, and limited public facilities. | [39,53] Reddy et al., 2018; Mwinuka & Mwemutsi, 2024 |

| F16 | Poor quality of public services | Perceived substandard quality in public institutions necessitates dependence on expensive private treatment. | [35,52] Berman et al., 2010; Rahman et al., 2024 |

| F17 | Hidden costs in public facilities | Supplementary payments for services, pharmaceuticals, or diagnostics add to concealed out-of-pocket expenditures. | [36,37,51] Van Doorslaer et al., 2007; Wright et al., 2025; Enemuwe & Oyibo, 2025 |

| Aspect: Policy and governance-related issues | |||

| F18 | Ineffective and inadequate public insurance | Restricted and limited benefit packages within public insurance programs. | [34,46,49] Wagstaff et al., 2018; Sarkar et al., 2025; Abodi et al., 2025 |

| F19 | Ineffective resource allocation | Insufficient support in economically disadvantaged states or districts exacerbates susceptibility to CHCE. | [45,53] Reddy et al., 2018; Gul et al., 2024 |

| F20 | Ineffective health governance and accountability measures | Leakage, corruption, and inefficiency in budget allocation diminish access to affordable healthcare. | [46,52] Berman et al., 2010; Abodi et al., 2025 |

| F21 | Lack of robust regulation for the private healthcare sector | Unregulated pricing, insufficient transparency, and profit-oriented tactics drive up treatment costs. | [35,36,51] Van Doorslaer et al., 2007; Rahman et al., 2024; Wright et al., 2025 |

| Aspect: Cultural and behavioral issues | |||

| F22 | Poor health-seeking behavior and delay in care | Delayed or unsuitable treatment-seeking exacerbates illness severity and expenses. | [47,48,50] Xu et al., 2003; Mohsin et al., 2024; Mulupi et al., 2025 |

| F23 | Lack of trust in public services | Confidence in private healthcare and cultural inhibitions about public services, despite their high costs, lead to a preference for CHCE. | [35,36,49] Wagstaff et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2024; Wright et al., 2025 |

| F24 | Gender disparity in decision-making | The restricted autonomy of women in healthcare expenditure decisions may result in delayed care and higher overall healthcare costs. | [37,47,53] Reddy et al., 2018; Mohsin et al., 2024; Enemuwe & Oyibo, 2025 |

| Demographic Variable | Category | Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | 18–25 | 33 | 13.2 |

| 26–35 | 60 | 24.0 | |

| 36–45 | 85 | 34.0 | |

| 46–55 | 47 | 18.8 | |

| 56+ | 25 | 10.0 | |

| Total | 250 | 100.0 | |

| Income Group (monthly) | <10 k | 75 | 30.0 |

| 10 k–20 k | 85 | 34.0 | |

| 20 k–30 k | 60 | 24.0 | |

| >30 k | 30 | 12.0 | |

| Total | 250 | 100.0 | |

| Education Level | School level | 100 | 40.0 |

| Undergraduate | 87 | 34.8 | |

| Post-graduate & above | 63 | 25.2 | |

| Total | 250 | 100.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 192 | 76.8 |

| Female | 58 | 23.2 | |

| Total | 250 | 100.0 |

| Category | Segment | Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (Years) | Less than 5 years | 5 | 16.7 |

| 6 to 10 | 10 | 33.3 | |

| 10 to 15 | 8 | 26.7 | |

| More than 15 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Education Level | Masters | 18 | 60.0 |

| Ph.D. | 12 | 40.0 | |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Expertise | Rural development | 12 | 40.0 |

| Public health | 4 | 13.3 | |

| NGOs | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Others | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 |

| Determinant | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | 102.9524 | 100.8571 | 98.47619 | 97.52381 | 98.90476 | 102.9048 |

| Weight | 0.04365 | 0.04276 | 0.04175 | 0.04134 | 0.04193 | 0.04363 |

| Rank | 1 | 4 | 11 | 15 | 8 | 2 |

| Determinant | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 |

| γ | 96.85714 | 95.14286 | 100.7143 | 102.1905 | 95.80952 | 97.57143 |

| Weight | 0.04106 | 0.04034 | 0.04270 | 0.04332 | 0.04062 | 0.04136 |

| Rank | 18 | 23 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 14 |

| Determinant | F13 | F14 | F15 | F16 | F17 | F18 |

| γ | 95.85714 | 100.3333 | 98.52381 | 98.85714 | 94.85714 | 96.90476 |

| Weight | 0.04064 | 0.04254 | 0.04177 | 0.04191 | 0.04021 | 0.04108 |

| Rank | 19 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 24 | 17 |

| Determinant | F19 | F20 | F21 | F22 | F23 | F24 |

| γ | 95.14286 | 99.47619 | 95.61905 | 97.42857 | 97.95238 | 97.95238 |

| Weight | 0.04034 | 0.04217 | 0.04054 | 0.04130 | 0.04153 | 0.04153 |

| Rank | 22 | 7 | 21 | 16 | 13 | 12 |

| Determinant | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | 19.71429 | 17.71739 | 16.88768 | 16.44348 | 16.19928 | 19.18012 |

| Weight | 0.05340 | 0.04799 | 0.04575 | 0.04454 | 0.04388 | 0.05196 |

| Rank | 1 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 2 |

| Determinant | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 |

| γ | 13.52174 | 13.43478 | 15.43478 | 18.46584 | 13.0942 | 14.43478 |

| Weight | 0.03663 | 0.03639 | 0.04181 | 0.05002 | 0.03547 | 0.03910 |

| Rank | 19 | 21 | 11 | 3 | 23 | 14 |

| Determinant | F13 | F14 | F15 | F16 | F17 | F18 |

| γ | 13.68841 | 16.6646 | 16.54348 | 15.35507 | 13.47826 | 14.21739 |

| Weight | 0.03708 | 0.04514 | 0.04481 | 0.04160 | 0.03651 | 0.03851 |

| Rank | 18 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 20 | 15 |

| Determinant | F19 | F20 | F21 | F22 | F23 | F24 |

| γ | 13.26087 | 16.70186 | 14.01449 | 11.47826 | 15.31159 | 13.90833 |

| Weight | 0.03592 | 0.04524 | 0.03796 | 0.03109 | 0.04148 | 0.03768 |

| Rank | 22 | 6 | 16 | 24 | 13 | 17 |

| Method | LBWA | SWARA | CIMAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| FullEX | 0.982 * | 0.988 * | 0.984 * |

| S/L | Code | Determinants of Catastrophic Health Expenditure | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F1 | Low household income level | 1 |

| 2 | F2 | Lack of job security | 4 |

| 3 | F3 | Low education level | 6 |

| 4 | F4 | Lack of assets and financial resilience | 9 |

| 5 | F5 | Disparity in rural economic conditions | 10 |

| 6 | F6 | Presence of dependent households | 2 |

| 7 | F10 | Frequent birth rate and child health vulnerability | 3 |

| 8 | F14 | Absence of prepayment or risk-pooling mechanisms | 5 |

| 9 | F15 | Ineffective referral system in healthcare facilities | 8 |

| 10 | F20 | Ineffective health governance and accountability measures | 7 |

| Determinants | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | V | V | V | O | V | O | O | O | |

| 2 | A | V | V | O | O | O | O | O | ||

| 3 | V | V | O | V | V | O | O | |||

| 4 | V | A | V | A | O | O | ||||

| 5 | A | A | A | A | A | |||||

| 6 | A | V | O | O | ||||||

| 7 | A | O | A | |||||||

| 8 | A | X | ||||||||

| 9 | X | |||||||||

| 10 |

| Determinants | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Driving Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Dependence Power | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Determinants | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Driving Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 10 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1* | 10 |

| 3 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 10 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 7 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 7 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 7 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 7 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Dependence Power | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Determinants | Reachability Set | Antecedent Set | Intersection Set | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 3 |

| 2 | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 3 |

| 3 | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 1, 2, 3, | 3 |

| 4 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

| 5 | 5, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 5, | 1 |

| 6 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

| 7 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

| 8 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

| 9 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

| 10 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarika, S.K.; Choudhury, S.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, B.; Chatterjee, P. A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Explore Determinants of Catastrophic Healthcare Expenses. Societies 2025, 15, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120353

Jarika SK, Choudhury S, Biswas S, Biswas B, Chatterjee P. A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Explore Determinants of Catastrophic Healthcare Expenses. Societies. 2025; 15(12):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120353

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarika, Savita Kumari, Shovona Choudhury, Sanjib Biswas, Biplab Biswas, and Prasenjit Chatterjee. 2025. "A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Explore Determinants of Catastrophic Healthcare Expenses" Societies 15, no. 12: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120353

APA StyleJarika, S. K., Choudhury, S., Biswas, S., Biswas, B., & Chatterjee, P. (2025). A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Explore Determinants of Catastrophic Healthcare Expenses. Societies, 15(12), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120353