A Thematic Analysis Exploring the Experiences of Ableism for People Living with Cerebral Palsy

Abstract

1. Literature Review

- To investigate how people with CP understand and perceive benevolent ableism in their daily lives.

- To examine how restrictions on independence occur in social domains such as community, family, and work.

- To explore the emergence of other forms of ableism in disabled people’s experiences.

2. Methodology Design

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Ethical Considerations

4. Findings and Discussion

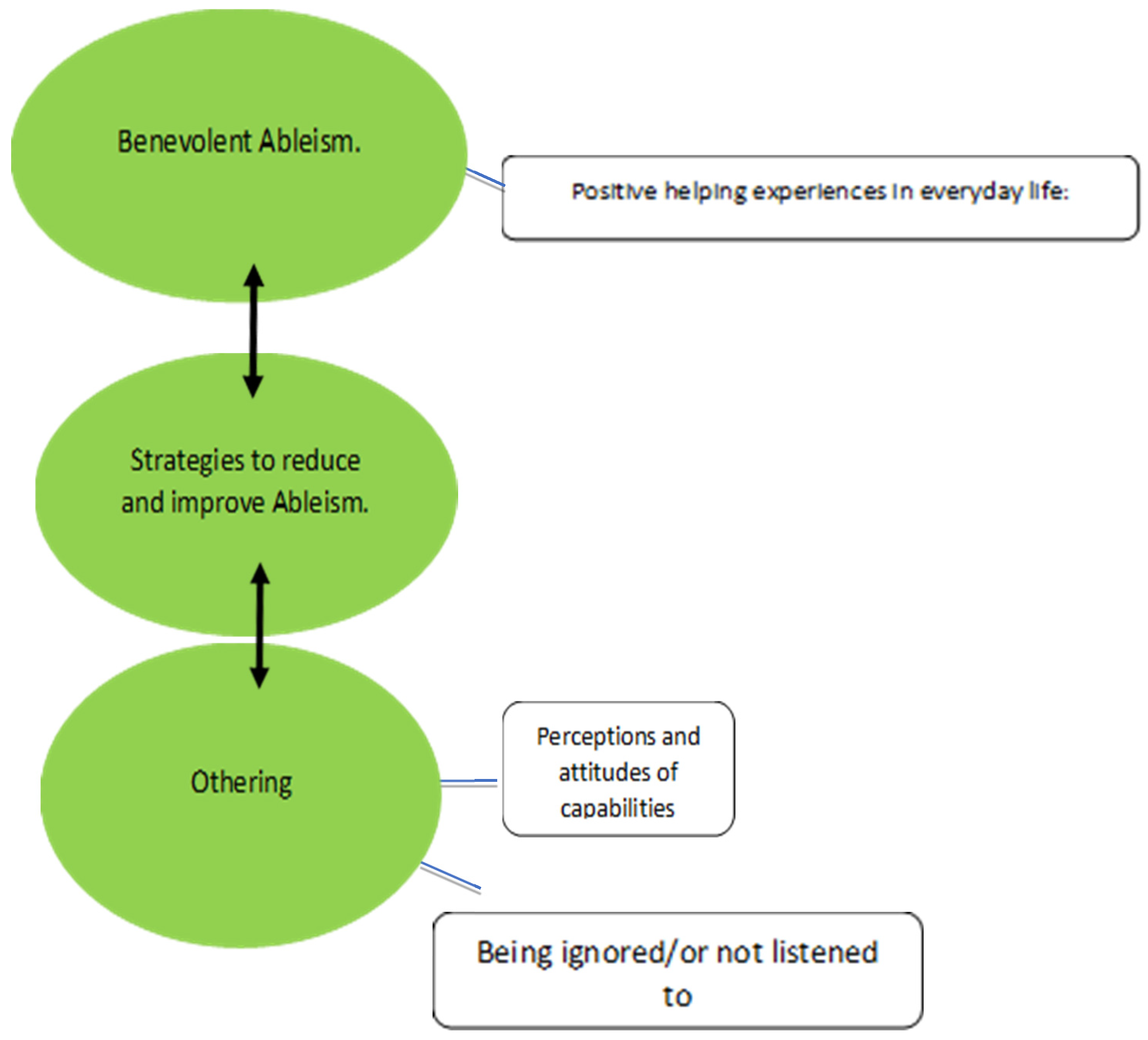

4.1. Theme 1: Benevolent Ableism

‘I find that being belittled is the worst bit about it (…) and sometimes it is worse than not helping at all. If they assume that they know what you need or what you want. Sometimes—because I do not have the use of both hands, I only have the use of one and they hand me things to the wrong side, and you are going (…) why are you doing that? Because you are too busy assuming and not seeing what I find quite challenging’.(Claire, 64–71)

‘They are just trying to help, but it just comes off wrong’.(Lucas, 51)

‘I understand that when someone tries to help me, they are doing so with good intentions. The problem is that they keep asking even though I can do it myself’.(Ryan, 209–213)

‘Doing stuff like cooking—my mum will just like try and get involved and she’s just like, are you struggling? No, mom, please let me do this. Like I need to learn. I know she’s doing because she cares, but you know you need to do it for your independence’.(Ben, 377–380)

‘We were leaving and I stopped to do my shoe up. The gentleman in question gave me a round of applause! It was unnecessary and very condescending’.(Claire, email)

Subtheme 1: Positive Helping Experiences in Everyday Life

‘I didn’t think I was different from everyone else because my parents enabled me. We did things together so that I could take part in activities that were really inspiring for me’.(Claire, 347–351)

‘What I liked about university is that it was independent; the support was there if I needed it, and it wasn’t actually in the classes, which I preferred because then I could just be like everybody else’.(Ben, 651–654)

4.2. Theme 2: Strategies to Improve and Reduce Ableism

‘Education is essential because once we have it, interactions become much more comfortable for both people’.(Charlotte, 1897–1898)

‘Having the right awareness shapes the way you approach the situation (interactions with disabled individuals’.(Ryan, 2238)

‘I’d also appreciate it if the person was patient, since while we may appear different, patience helps you to get to know us better and discover who we are as individuals, beyond the challenges you may see on the surface’.(Charlotte, 1390–1393)

‘Do you need any help, or is it okay if I talk about the help you need?’—‘Yeah, of course it is’.(Claire, 1489–1490)

‘More direct, but conscientious’ and ‘without overdoing it’.(Lucas, 1449)

4.3. Theme 3: Othering

‘Couldn’t stop staring at him ‘’…’’ he just could not take his eyes off him’.(Lucas, 493–500)

‘I also hate it when people stare; it makes me feel so uncomfortable ‘’…’’ I get more shaky because I get more self-conscious’.(Charlotte, 1388–1390)

‘It feels a bit patronising when they ask, ‘So, would Lucas like a drink?’ as if he were a child. He’s 35, not 5. He’s perfectly capable of being spoken to like any other adult’.(Lucas, 32–35)

4.3.1. Subtheme 1: Being Ignored/or Not Listened to

‘I’ve also had experience where doctors (...) they make their own decisions for me and it can be quite frustrating, because we know more about our body, about the difficulties that we have (...) because yes they have an abundance of knowledge but it is pretty frustrating when they don’t acknowledge, that you also have knowledge about what you’re suffering’.(Charlotte, 1097–1108)

‘I said I need some reasonable adjustments for this, and they didn’t get it (...) the things I was asking for weren’t that difficult’.(Claire, 1699–1719)

4.3.2. Subtheme 2: Perceptions and Attitudes of Capabilities

‘I think it’s easy to put us into boxes (...) teachers think it is best for you to be in small classrooms or doing something that’s less complex (...) and it does affect your future essentially (...) you think that I could only achieve certain things. I think it holds you back as you grow older and how you perceive yourself’.(Charlotte, 92–115)

‘When there was a test and if I got a high score students would say oh, she got help from that scribe, that really knocked down my confidence’.(Charlotte, 753–755)

5. Study Limitations and Advantages

6. Future Research and Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirk-Wade, E. UK Disability Statistics: Prevalence and Life Experiences; House of Commons Library Research Briefing No. 09602; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haegele, J.A.; Hodge, S. Disability Discourse: Overview and Critiques of the Medical and Social Models. Quest 2016, 68, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. (Ed.) The Social Model in Context. In Understanding Disability from Theory to Practice; Palgrave: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Olkin, R. Could You Hold the Door for Me? Including Disability in Diversity. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2002, 8, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, C. Challenging the Authority of the Medical Definition of Disability: An Analysis of the Resistance to the Social Constructionist Paradigm. Disabil. Soc. 2003, 18, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R. The Social Model of Disability. Br. J. Healthc. Assist. 2010, 4, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. The Social Model of Disability: Thirty Years On. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. The Social Model of Disability. In The Disability Studies Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Samahat, A.M. What Good Is the Social Model of Disability. Univ. Chi. Law Rev. 2007, 74, 1251–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.S. Outsider Privileges Can Lead to Insider Disadvantages: Some Psychosocial Aspects of Ableism. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F. Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G. Is There an End to Out-Able? Is There an End to the Rat Race for Abilities? M/C J. 2008, 11, mcj.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, K.R.; Dunn, D.S. Ableism Special Issue Introduction. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nario-Redmond, M.R.; Kemerling, A.A.; Silverman, A. Hostile, Benevolent, and Ambivalent Ableism: Contemporary Manifestations. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 726–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Dis/Entangling Critical Disability Studies. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder-Dawe, O.; Witten, K.; Carroll, P. Being the Body in Question: Young People’s Accounts of Everyday Ableism, Visibility and Disability. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. The BIAS Map: Behaviors from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, S.L.; Tse, C.; Logel, C.; Spencer, S.J. When Seeing Stigma Creates Paternalism: Learning about Disadvantage Leads to Perceptions of Incompetence. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2022, 25, 1202–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.M.; Galgay, C.E. Microaggressive Experiences of People with Disabilities. In Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact; Sue, D.W., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Godley, D. Dis/ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F. Cerebral palsy: Definition, assessment and rehabilitation. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 111, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gillmore, L.; Wotherspoon, J. Perceptions of Cerebral Palsy in the Australian Community. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 70, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.A.; Morton, T.A.; Ryan, M.K. Negotiating identity: A qualitative analysis of stigma and support seeking for individuals with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Avery, A.; Bailey, R.; Bell, B.; Coulson, N.; Luke, R.; McLaughlin, J.; Logan, P. The everydayness of falling: Consequences and management for adults with cerebral palsy across the life course. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 47, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olkin, R.; Hayward, H.; Abbene, M.S.; VanHeel, G. The Experiences of Microaggressions Against Women with Visible and Invisible Disabilities. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 757–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattari, S.K. Ableist Microaggressions and the Mental Health of Disabled Adults. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, K.; Tamaian, A.; Klest, B. Impact of Ableist Microaggressions on University Students with Self-Identified Disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 1441–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Silverman, A.; Gwinn, J.D.; Dovidio, J.F. Independent or Ungrateful? Consequences of Confronting Patronizing Help for People with Disabilities. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2015, 18, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, K.J.; Israel, T.; Nylund-Gibson, K. Development and Validation of the Ableist Microaggressions Scale. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 45, 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, I. The Focus Groups in Social Research: Advantages and Disadvantages. Qual. Quant. 2012, 46, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Moloney, M.E. Intersectionality, Work, and Well-Being: The Effects of Gender and Disability. Gender Soc. 2019, 33, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, C.A.; Gannotti, M.; Cohen, J.; Hurvitz, E. Priority setting for multicenter research among adults with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 5307–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Katz, L. The Use of Focus Group Methodology in Education: Some Theoretical and Practical Considerations. IEJLL Int. Electron. J. Leadersh. Learn. 2001, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, P. Focus Group Methodology. Part 1: Design Considerations. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2017, 24, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, F.; Tse, C.; Logel, C.; Spencer, S. Focus-Group Interview and Data Analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 1202–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of Data Collection in Qualitative Research: Interviews and Focus Groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir-Döke, D.; Herbert, J.T. Development and Validation of the Ableist Microaggression Impact Questionnaire. Rehabil. Counsel. Bull. 2022, 66, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, J.A.; Keller, V.N.; Chopik, W.J. Demographic, Experiential, and Temporal Variation in Ableism. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W.; Bucceri, J.; Lin, A.I.; Nadal, K.L.; Torino, G.C. Racial Microaggressions and the Asian American Experience. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2009, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S. Child and Youth Experiences and Perspectives of Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, E.; Larivière-Bastien, D.; Bell, E.; Majnemer, A.; Shevell, M. Respect for Autonomy in the Healthcare Context: Observations from a Qualitative Study of Young Adults with Cerebral Palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 39, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakow, L.F. Commentary: Interviews and Focus Groups as Critical and Cultural Methods. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2011, 88, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S.; Muhit, M. Using Qualitative Research Methods for Disability Research in Majority World Countries. Asia Pac. Disabil. Rehabil. J. 2003, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Niesz, T.; Koch, L.; Rumrill, P.D. The Empowerment of People with Disabilities Through Qualitative Research. Work 2008, 31, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, B.; Killeen, M. Research on the Lives of Persons with Disabilities: The Emerging Importance of Qualitative Research Methodologies. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2002, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, H. Rebuilding a Classic: The Social Construction of Reality at 50. Cult. Sociol. 2016, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.R. Toward Inclusive Theory: Disability as Social Construction. NASPA J. 1996, 33, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; de Lacey, S. Qualitative Research Methods: When to Use Them and How to Judge Them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggerstaff, D. Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology. In Psychology: Selected Papers; Rossi, G., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, L.T. The Strengths and Weaknesses of Research Methodology: Comparison and Complimentary between Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 19, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.; Gibson, S.; Riley, S. Doing Your Qualitative Psychology Project, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, J.N.; Cho, Y.; Lochmiller, C.R. Learning to Do Qualitative Data Analysis: A Starting Point. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinheksel, A.J.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Tawfik, H.; Wyatt, T.R. Demystifying Content Analysis. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchin, R. The Researched Opinions on Research: Disabled People and Disability Research. Disabil. Soc. 2000, 15, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Lawthom, R.; Runswick-Cole, K. Community-Based Arts Research for People with Learning Disabilities: Challenging Misconceptions About Learning Disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 204–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shildrick, M. “Why Should Our Bodies End at the Skin?”: Embodiment, Boundaries, and Somatechnics. Hypatia 2014, 30, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the 1980s. In Feminism/Postmodernism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Bowlby, S. Bodies and Spaces: An Exploration of Disabled People’s Experiences of Public Space. Environ. Plan. Soc. Space 1997, 15, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. Cultural Representation of Disabled People: Dustbins for Disavowal. Disabil. Soc. 1994, 9, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Munyi, C.W. Past and Present Perceptions Towards Disability: A Historical Perspective. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.Y. Overprotection and Lowered Expectations of Persons with Disabilities: The Unforeseen Consequences. Work 2006, 27, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppsson, S.; Brandenburg, D. Patronising Praise. J. Ethics 2022, 26, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.E.; Finkelstein, L.M. An Experimental Investigation into Judgment and Behavioral Implications of Disability-Based Stereotypes in Simulated Work Decisions: Evidence of Shifting Standards. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, G.; Willis, C.; Shields, N. Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity Participation for Young People and Adults with Childhood-Onset Physical Disability: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Roberts, R.; Bowman, G.; Crettenden, A. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Participation for Children with Physical Disability: Comparing and Contrasting the Views of Children, Young People, and Their Clinicians. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfson, L. Family Well-Being and Disabled Children: A Psychosocial Model of Disability-Related Child Behaviour Problems. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolac, A.; Jokić, C.S. Understanding the Everyday Experience of Persons with Physical Disabilities: Building a Model of Social and Occupational Participation. J. Occup. Sci. 2019, 26, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, D.O.; Eckstein, N.J. How People with Disabilities Communicatively Manage Assistance: Helping As Instrumental Social Support. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2003, 31, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.; O’Mahony, P. Physically Disabled Adults’ Perceptions of Personal Autonomy: Impact on Occupational Engagement. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2015, 35, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, L.; Kreschmer, J.M.; James, T.G.; Junior, J.D.; DeShong, G.L.; Parker, S.; Meade, M.A. Ableism and Contours of the Attitudinal Environment as Identified by Adults with Long-Term Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C. An Investigation of Attitude Change in Inclusive College Classes Including Young Adults with an Intellectual Disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 9, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, K.T.; Nadler, D.R. Reducing Ableism and the Social Exclusion of People with Disabilities: Positive Impacts of Openness and Education. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2022, 27, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modood, T.; Thompson, S. Othering, Alienation and Establishment. Polit. Stud. 2022, 70, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland-Thomson, R. Staring at the Other. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2005, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, R.; Yoshida, K.; Eacrett, E.; Rose, N. Meaning of Staring and the Starer–Staree Relationship Related to Men Living with Acquired Spinal Cord Injuries. Am. J. Mens Health 2018, 12, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robey, K.L.; Beckley, L.; Kirschner, M. Implicit Infantilizing Attitudes about Disability. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2006, 18, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesener, J.J.; Mills, J. An Experimental Study of Disability Spread: Talking to an Adult in a Wheelchair Like a Child. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Guzmán, D.M.; Reynolds, J.M. The Harm of Ableism: Medical Error and Epistemic Injustice. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2019, 29, 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries McClintock, H.F.; Barg, F.K.; Katz, S.P.; Stineman, M.G.; Krueger, A.; Colletti, P.M.; Boellstorff, T.; Bogner, H.R. Health Care Experiences and Perceptions among People with and without Disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, C.K. Resisting Ableism in Deliberately Developmental Organizations: A Discursive Analysis of the Identity Work of Employees with Disabilities. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2021, 32, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agran, M.; Jackson, L.; Kurth, J.A.; Ryndak, D.; Burnette, K.; Jameson, M.; Zagona, A.; Fitzpatrick, H.; Wehmeyer, M. Why Aren’t Students with Severe Disabilities Being Placed in General Education Classrooms: Examining the Relations among Classroom Placement, Learner Outcomes, and Other Factors. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2020, 45, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalvani, P. Disability, Stigma and Otherness: Perspectives of Parents and Teachers. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2015, 62, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction; SAGE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, D.; Lawthom, R.; Liddiard, K.; Runswick-Cole, K. Provocations for Critical Disability Studies. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 972–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Merry, J. Inclusive Disability Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1935–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, T.; Barbour, R.; Harris, J. Using Focus Groups in Disability Research. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, C.; Wolbring, G. Coverage of Disabled People in Environmental-Education-Focused Academic Literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with Persons with Disabilities: UN Flagship Report on Disability and Development 2018; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/monitoring-and-evaluation-of-inclusive-development/medd.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Danieli, A.; Woodhams, C. Emancipatory Research Methodology and Disability: A Critique. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Cerebral Palsy (CP) | Do not have CP |

| Lived in UK | |

| Age range of 19–55 | Under 18 |

| Include participants with language barriers who can communicate through translators to speak on their behalf. | |

| Pseudonyms | Gender | Age | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lucas and Paul | Male | 35 | Cerebral Palsy |

| Charlotte | Female | 25 | Cerebral Palsy |

| Claire | Female | 55 | Cerebral Palsy |

| Ryan | Male | 19 | Cerebral Palsy |

| Ben | Male | 26 | Cerebral Palsy |

| Pseudonyms | Method of Data Collection |

|---|---|

| Claire | Focus group |

| Charlotte | Focus group |

| Lucas and Paul | Focus group |

| Ryan | Informal interviews |

| Ben | Informal interviews |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McQuillan, F.G.; Sorte, R. A Thematic Analysis Exploring the Experiences of Ableism for People Living with Cerebral Palsy. Societies 2025, 15, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120343

McQuillan FG, Sorte R. A Thematic Analysis Exploring the Experiences of Ableism for People Living with Cerebral Palsy. Societies. 2025; 15(12):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120343

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcQuillan, Francesca Georgia, and Rossella Sorte. 2025. "A Thematic Analysis Exploring the Experiences of Ableism for People Living with Cerebral Palsy" Societies 15, no. 12: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120343

APA StyleMcQuillan, F. G., & Sorte, R. (2025). A Thematic Analysis Exploring the Experiences of Ableism for People Living with Cerebral Palsy. Societies, 15(12), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120343