Organizational Innovation and Managerial Burnout: Implications for Well-Being and Social Sustainability in a Transition Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Positioning

2.2. Theoretical Background of Innovation as a Research Factor

2.3. Theoretical Background of Burnout as a Research Factor

2.4. The Relationship Between Innovation and Burnout

2.5. Leadership and Organizational Culture as Moderators of the Relationship Between Innovation and Burnout

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Problem

3.2. Research Subject

3.3. Research Objective and Hypotheses

- RQ1:

- Does the effect of innovations on professional burnout differ depending on the gender of employees?

- RQ2:

- Does the supervisor’s gender moderate the relationship between innovation and burnout among middle managers?

- RQ3:

- How do ownership structure (public vs. private) and organization type (manufacturing vs. service) shape the effect of innovation on burnout?

3.4. Research Design and Procedure

3.5. Instruments

- Questionnaire for measuring innovation—Organizational innovation was measured across three dimensions: product and service innovation, process innovation, and administrative innovation. The instrument was constructed based on validated scales from previous research [84,85,86]. A total of 8 items were used;

- Questionnaire for measuring professional burnout—The level of professional burnout was assessed using a shortened version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), developed by Christensen et al. [87]. The original instrument contains three dimensions: personal burnout, burnout at work, and burnout in contact with clients. Within this research, only the dimension of burnout at work was used, with a total of 7 items. The decision to use only the work-related dimension of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) was based on the specific research focus of this study. Since the objective was to examine the impact of organizational innovation on job-related stressors experienced by middle managers, the “burnout at work” subscale was deemed most relevant. The other two subscales, personal burnout and burnout in contact with clients, reflect broader aspects of fatigue and exhaustion that may be influenced by non-work or interpersonal factors outside the organizational context. Therefore, the use of the work-related subscale provided a more direct and conceptually aligned measure of burnout as a workplace phenomenon arising from organizational processes and demands. To assess the comparability of measurement across subgroups, a measurement invariance analysis was conducted by gender and sector. The results indicated satisfactory configural and metric invariance, suggesting that the instrument measures the same latent construct across groups and that comparisons between them are interpretatively valid;

- Moderator variables—The examined leadership styles include transformational and transactional leadership as measured by the scales developed by Podsakoff et al. [88,89], Podsakoff & Organ [90] and MacKenzie et al. [91]. Ethical leadership was measured using the scale of Brown et al. [92], and punitive leader behavior was measured by a dimension from the scale of Podsakoff et al. [88] and MacKenzie et al. [91]. The leader–member exchange (LMX) was measured by the Liden and Maslyn [93] scale, and regarding organizational culture, the dimensions of power distance, human orientation, performance orientation and collectivism are from the GLOBE study [94,95,96];

- Socio-demographic data—The questionnaire included basic socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, including gender, age, level of education, length of service and sector of activity. All socio-demographic responses were collected in categorical form.

3.6. Operational Definitions of Key Variables

3.7. Measurement Validity and Reliability

3.8. Ethics

3.9. Data Analysis

- Descriptive statistics—used to display the basic characteristics of the sample and the examined variables;

- Correlation analysis—the Pearson correlation coefficient was applied to examine the linear relationship between the dimensions of organizational innovation and the level of professional burnout;

- Multiple linear regression analysis—used to assess the individual contribution of each innovation dimension in explaining the variance of professional burnout, as well as to test the statistical significance of the regression model as a whole;

- Hierarchical multiple regression analysis—conducted in order to examine the effects of moderator variables and their interactions with dimensions of innovation, with the evaluation of the change in the explained variance at each modeling step;

- Verification of regression assumptions included the following:

- Multicollinearity—based on values Tolerance and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor);

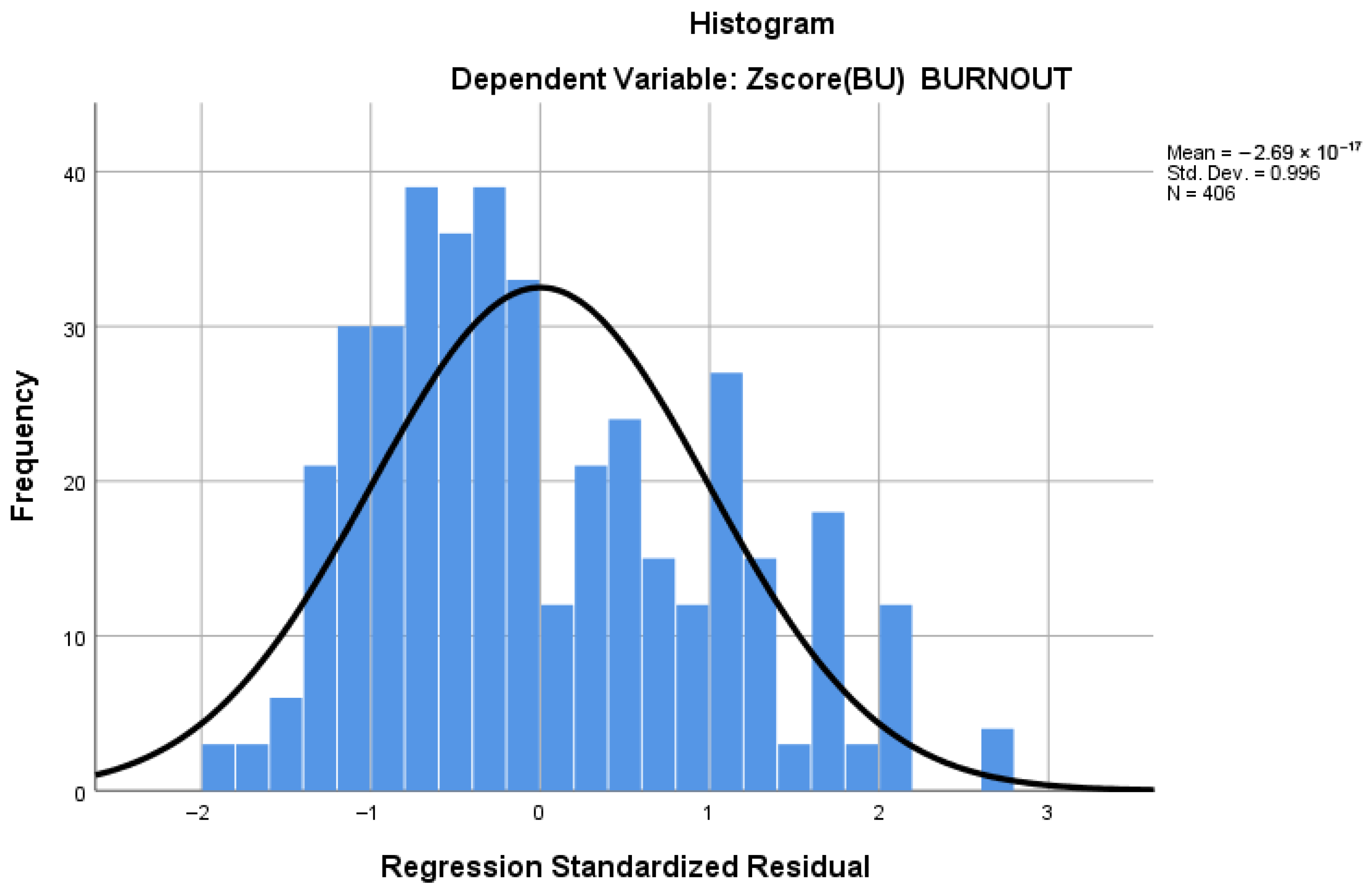

- Normality of residuals—assessed using a normal P–P plot;

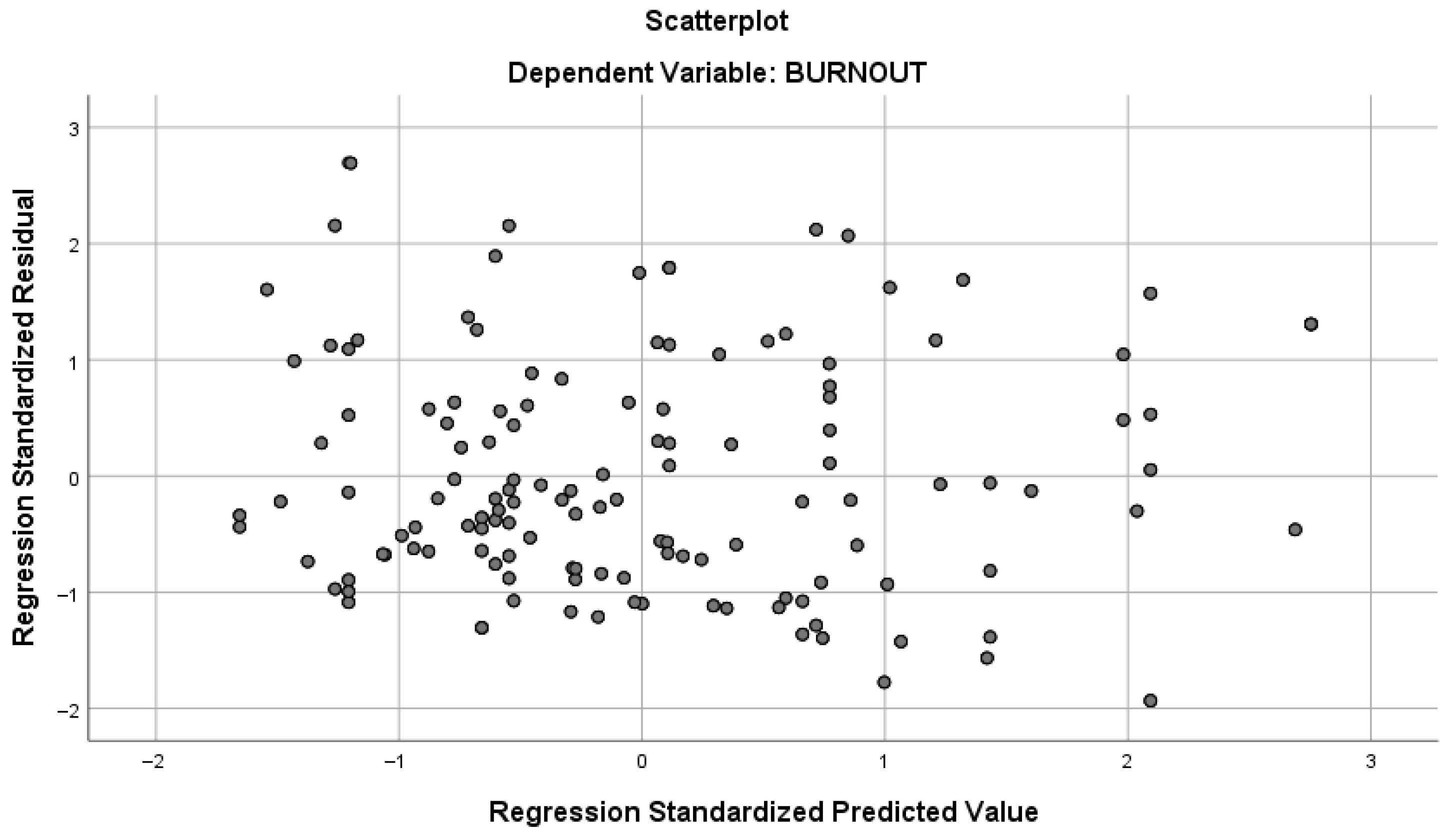

- Homoscedasticity—examined through the scatterplot of standardized residuals versus predicted values.

3.10. Rationale for the Selection of Analytical Techniques

3.11. Research Sample

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Testing Assumptions of Regression Analysis

- Product and service innovation: Tolerance = 0.603; VIF = 1.658;

- Process innovation: Tolerance = 0.558; VIF = 1.791;

- Administrative innovation: Tolerance = 0.514; VIF = 1.946.

4.3.2. Regression Model Estimation

4.3.3. Overall Model Significance—ANOVA

4.3.4. Individual Predictor Contribution

4.3.5. Statistical Analysis and Reporting Transparency

4.3.6. Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis with Included Moderators

4.4. Evaluation of Model Parsimony and Stability

4.5. Assessment of Multicollinearity and Suppressor Effects

4.6. Interpreting Counterintuitive Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Specific Hypotheses (H2–H4)

5.2. Discussion of Moderator Hypotheses (H5–H7)

5.3. Answers to Research Questions (RQ1–RQ3)

5.4. Discussion of Gender and Sector Differences

5.5. Practical Implications for Management and HR Practices

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMX | Leader–Member Relationship |

| HR | Human Resource |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| β | Standardized Regression Coefficient |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| M | Mean |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

Appendix A

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| My company is a leader in introducing new products/services. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company introduces innovations in the commercialization and logistics of its products/services. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company introduces numerous changes to its business processes. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company is a leader in introducing new ways of performing business processes. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company encourages the development of processes that improve quality and reduce costs. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company uses advanced management methods. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company introduces innovations in its strategy and way of doing business. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My company introduces innovations in its organizational structure and management systems. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| I feel exhausted at the end of the work day. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I feel exhausted in the morning just thinking about another day at work. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I feel that every working hour is hard and tiring. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| When I have free time, I feel that I lack energy for family and friends. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My job is emotionally draining. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My job frustrates me. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I feel like I am burning out because of my job. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| My supervisor has a clear vision. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor provides an appropriate role model for conducting work, one that is oriented toward achieving goals. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor facilitates the acceptance of group goals. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor makes it clear that they expect me to consistently give my best. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor insists solely on achieving the best possible results. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor accepts only the best solution. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor acts in a way that takes my feelings into account. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor takes my personal feelings into consideration before taking action. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor demonstrates respect for my personal feelings. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor interacts with me in a manner that takes my personal feelings into account. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor inspires me to think about old problems in new ways. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor asks questions that prompt me to think critically. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor encourages me to re-examine the ways in which I carry out my work. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor offers ideas that have inspired me to re-examine some of the fundamental assumptions about my work. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor provides positive feedback when I do something well. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor gives me special recognition when I perform tasks at a high level. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor praises me when I exceed my usual level of productivity. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor consistently acknowledges the good results I achieve. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor expresses dissatisfaction when I deliver low performance. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor makes it clear to me when I am performing poorly. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor points out when my productivity is not at its usual level. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| My supervisor listens to their employees. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor praises employees who act ethically and responsibly. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor behaves ethically and responsibly in their private life as well. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor places the interests of employees as a priority. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor makes fair and well-considered decisions. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor is a person who can be trusted. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor talks with employees about business ethics. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor demonstrates through personal example how to work in an ethical manner. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor recognizes success not only based on the results achieved, but also on the manner in which those results were attained. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor always takes into account what is morally right when making decisions. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| I respect my supervisor as a person. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor is the kind of person people would like to have as a friend. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Working with my supervisor is enjoyable. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor defends my actions to other superiors, even when they are not fully familiar with the issue. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor would stand up for me in the event of a “challenge” or criticism from others. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| My supervisor would come to my defense even if I made an unintentional mistake. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I do what my supervisor asks of me, even when it goes beyond my formal job duties. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I am willing to put in additional effort in order to meet my supervisor’s expectations. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I have no difficulty giving my utmost when it comes to my supervisor. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I am impressed by the knowledge my supervisor possesses in their field of work. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I respect my supervisor’s knowledge and competencies. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| I admire my supervisor’s professional skills. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| In my company, an individual’s influence is primarily based on: | 1–7 Likert (Their abilities and contributions–The authority that comes with their position) |

| In my company, employees are expected to: | 1–7 Likert (Question their supervisor’s decisions when they disagree with them–Obey the supervisor without questioning) |

| In my company, people who hold power tend to: | 1–7 Likert (Reduce social distance with those who have less power–Increase social distance from those who have less power) |

| In my company, people are generally: | 1–7 Likert (Inconsiderate toward others–Considerate toward others) |

| In my company, people generally: | 1–7 Likert (Lack concern for others–Show concern for others) |

| In my company, people are generally: | 1–7 Likert (Not sociable–Very sociable) |

| In my company, people are generally: | 1–7 Likert (Not generous–Very generous) |

| In my company, employees are encouraged to strive for continuous performance improvement. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| In my company, the greatest rewards are based: | 1–7 Likert (Solely on position or political connections–Solely on efficiency) |

| In my company, innovation aimed at improving performance is generally: | 1–7 Likert (Not rewarded–Significantly rewarded) |

| In my company, most employees willingly take on challenging work tasks. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| In my company, group members take pride in the individual accomplishments of their group manager. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| In my company, the group manager takes pride in the individual accomplishments of group members. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Employees are loyal to this company. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

| Members of my company: | 1–7 Likert (Are not proud to work here–Are very proud to work here) |

| My company demonstrates loyalty toward its employees. | 1–7 Likert (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree) |

Appendix B

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Std. Error of the Estimate | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.384 | 0.147 | 0.141 | 0.676 | 23.08 | 0.000 |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 5.424 | 0.269 | — | 20.157 | 0.000 | [4.895, 5.953] | — | — |

| Product and service innovation | 0.067 | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.901 | 0.368 | [−0.081, 0.214] | 0.387 | 2.582 |

| Process innovation | −0.118 | 0.111 | −0.111 | −1.070 | 0.285 | [−0.336, 0.099] | 0.198 | 5.042 |

| Administrative innovation | −0.347 | 0.110 | −0.320 | −3.144 | 0.002 | [−0.563, −0.130] | 0.207 | 4.828 |

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Std. Error of the Estimate | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.537 | 0.289 | 0.280 | 0.615 | 32.17 | 0.000 |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 4.944 | 0.269 | — | 18.38 | 0.000 | [4.415, 5.473] | — | — |

| Transformational leadership | −0.124 | 0.078 | −0.127 | −1.580 | 0.111 | [−0.277, 0.029] | 0.411 | 2.432 |

| High performance expectation | −0.166 | 0.074 | −0.138 | −2.250 | 0.026 | [−0.313, −0.020] | 0.508 | 1.968 |

| Intellectual stimulation | −0.108 | 0.079 | −0.106 | −1.360 | 0.177 | [−0.263, 0.048] | 0.469 | 2.134 |

| Rewards (incentives) | −0.218 | 0.066 | −0.231 | −3.320 | 0.001 | [−0.347, −0.089] | 0.553 | 1.808 |

| Punitive leadership behavior | 0.347 | 0.091 | 0.313 | 3.810 | 0.000 | [0.168, 0.525] | 0.537 | 1.862 |

References

- Gan, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Knowledge heterogeneity and corporate innovation performance: The mediating influence of task conflict and relationship conflict. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Dias, D.; Kneipp, J.M.; Bichueti, R.S.; Gomes, C.M. Fostering business model innovation for sustainability: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, A.; Musadieq, M.A.; Hutahayan, B.; Solimun, S. Creating a sustainable competitive advantage: The roles of technological innovation, knowledge management, and organizational agility. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 44, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, D. Innovating from the Inside Out? A Scoping Study Informing Organizational Innovation for Social Innovation. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2025, 49, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. Examining the influence of organizational structure and leadership on innovation in hybrid work settings: The mediating role of organizational culture in enhancing team collaboration and innovation outcomes. PREPRINT (Version 1). Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaker, J.; Munir, H.; Runeson, P.; Regnell, B.; Schrewelius, C. A survey on the perception of innovation in a large Product-Focused software organization. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switherland, 2015; pp. 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, K.B. Understanding innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, B.; Islam, M.O.; Kibria, H.; Barua, R. Analysis of creativity at the workplace through employee empowerment. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 33, 2547–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, G.; Calin, D. The role of organizational culture in Driving Innovation: A study of contemporary Business practice. Acta Univ. Cibiniensis Tech. Ser. 2024, 76, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y.; Cao, X. Understanding how organizational culture affects innovation Performance: A Management Context Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; De Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainalainen, A.; Korhonen, P.; Penttinen, M.A.; Liira, J. Job stress and burnout among Finnish municipal employees without depression or anxiety. Occup. Med. 2024, 74, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leskovic, L.; Gričar, S.; Folgieri, R.; Šugar, V.; Bojnec, Š. The effect of burnout experienced by nurses in retirement homes on human resources economics. Economies 2024, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E. Balancing act: Exploring the interplay of production pressure and innovation/flexibility climates on employee well-being. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2024, 34, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Yuan, Y.; Dou, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Yuan, Y. Where there is pressure, there is motivation? The impact of challenge-hindrance stressors on employees’ innovation performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1020764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement: A Meta-Analysis using the Job Demands-Resources model. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 126, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, J.L.; Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Constructive and destructive leadership in job demands-resources theory: A meta-analytic test of the motivational and health-impairment pathways. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 14, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.A.; García, G.M.; Calvo, J.A.; García, G.M. Hardiness as moderator of the relationship between structural and psychological empowerment on burnout in middle managers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 91, 362–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Salam, M.; Ullah, W.; Iqbal, S.; Shahid, M.N. Let the Employees Strengthen for a Sustainable Future: A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainable HRM. J. Policy Res. 2024, 10, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.; Pathak, G.S. Employee well-being and sustainable development: Can occupational stress play spoilsport. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2022, 18, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; McIntosh, T.; Reid, S.W.; Buckley, M.R. Corporate implementation of socially controversial CSR initiatives: Implications for human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 29, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.H.; Choi, J.N.; Du, J. Tired of innovations? Learned helplessness and fatigue in the context of continuous streams of innovation implementation. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1130–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Shahiri, H.; Wei, X. “I’m stressed!”: The work effect of process innovation on mental health. SSM-Popul. Health 2023, 21, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyadi, T.; Sulistiasih, S.; Rahmi, K.H.; Fahrudin, A.; Pramono, B. The impact of digital fatigue on employee productivity and well-being: A scoping literature review. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, E.; Vallejos, E.P.; Spence, A. Overloaded by information or worried about missing out on it: A quantitative study of stress, burnout, and mental health implications in the digital workplace. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, C.; Ionașcu, C.M.; Niță, A.M. Mapping Occupational Stress and Burnout in the Probation System: A Quantitative approach. Societies 2025, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćosić, D.P. Changes in work orientations in postsocialist Serbia. Südosteuropa 2020, 68, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezes, P.; Jeannot, G. Autonomy and managerial reforms in Europe: Let or make public managers manage? Public Adm. 2017, 96, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, S.; Milenović, M.; Krstić, I.; Veljković, M. Correlation between psychosocial work factors and the degree of stress. Work 2021, 69, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M.C. Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. How fairness perceptions make innovative behavior more or less stressful. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L.G.; Bakker, A.B. Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hamid, T.A.; Naveed, R.T.; Siddique, I.; Ryu, H.B.; Han, H. Preparing for the “black swan”: Reducing employee burnout in the hospitality sector through ethical leadership. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1009785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; González-Carrasco, M.; Miranda Ayala, R.A. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The impact of moral intensity and affective commitment. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N. Exploring the connections between destructive leadership styles, occupational pressures, support systems, and professional burnout in nursing: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustian, K.; Mubarok, E.S.; Zen, A.; Wiwin, W.; Malik, A.J. The impact of digital transformation on business models and competitive advantage. Technol. Soc. Perspect. (TACIT) 2023, 1, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, N.A.; Ewim, N.S.E.; Sam-Bulya, N.N.J.; Ajani, N.O.B. Strategic innovation in business models: Leveraging emerging technologies to gain a competitive advantage. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 3372–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Liao, M.; Wang, Y. Transportation infrastructure, market integration and corporate innovation. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 5427–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Hu, S.; Xia, H. How does the digital economy impact the green upgrading of manufacturing? Perspectives on technological innovation and resource allocation. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 5049–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soesetio, Y.; Rudiningtyas, D.A.; Rakhmad, A.A.N.; Wiliandri, R. Entrepreneurial orientation, innovation, competitiveness, and performance of Ultra-Micro and micro enterprises in Indonesia. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2024, 29, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnabuci, G.; Kovacs, B. Catalyzing categories: Category contrast and the creation of groundbreaking inventions. Acad. Manag. J. 2025, 68, 1084–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, J. Revealing academic networks’ impact: Driving innovation in Chinese high-tech enterprises. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 6853–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, D.; Jager, A.; Lerch, C.M. Fostering innovation by complementing human competences and emerging technologies: An industry 5.0 perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 63, 1126–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, J.E. Business model innovation and business concept innovation as the context of incremental innovation and radical innovation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, K. The relatioship between job demands and burnout across professions. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2025, 13, 436–447. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. How to measure burnout accurately and ethically. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021, 7, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S. Beliefs about burnout. Work Stress 2024, 39, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A.; Černe, M.; Popovič, A. Absorbed in technology but digitally overloaded: Interplay effects on gig workers’ burnout and creativity. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, K.P.; Aguinis, H. How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 65, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Creativity and emotional exhaustion in virtual work environments: The ambiguous role of work autonomy. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Workload, techno overload, and behavioral stress during COVID-19 emergency: The role of job crafting in Remote workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, R. Avoiding and Overcoming Burnout. IUP J. Soft Ski. 2025, 19, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Benevolent Climates and Burnout Prevention: Strategic Insights for HR Through Job Autonomy. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basar, M.; Duzcu, T. The burnout: A silent saboteur in in vitro fertilization laboratories. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2025, 42, 2497–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, N.; Camara, A.; Parker, G. How is Burnout Self-identified? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2025, 213, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, M.P.S.; Aguilar, E.G.; Llobet, M.P.; Estévez, M.C.V.; Jiménez, A.M.; Juanico, J.C. Retroalimentación Docencia-Asistencia-Docencia. Estudio Sobre Burnout en Enfermeras de Salud Mental Como Estrategia de Innovación y Calidad Docente. Dialnet. 2015. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5053578 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Horváthová, P.; Mokrá, K.; Stanovská, K.; Poláková, G. The Impact of Remote and Hybrid Work on the Perception of Burnout Syndrome: A Case Study. 2024. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ssi/jouesi/v11y2024i4p91-104.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Hammond, M.; Cross, C.; Farrell, C.; Eubanks, D. Burnout and innovative work behaviours for survivors of downsizing: An investigation of boundary conditions. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.K.; Abler, M. Emotional exhaustion and innovation in the workplace: A longitudinal study. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zheng, S.; Chen, L. Promoting sustainable development of organizations: Performance pressure, workplace fun, and employee ambidextrous innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F. Feeling exhausted? Let’s Play—How play in work relates to experienced burnout and innovation behaviors. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 16, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Shen, Y. Can process digitization improve firm innovation performance? Process digitization as job resources and demands. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Digital Realities: Role Stress, Social Media Burnout, and E-Cigarette Behavior in Post-90 s Urban White-Collar Workers. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 5999–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Siu, K.W.M.; Bühring, J.; Villani, C. The Relationship between Creative Self-Efficacy, Achievement Motivation, and Job Burnout among Designers in China’s e-Market. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristana, I.N.; Puspitawati, N.M.D.; Salain, P.P.P.; Koval, V.; Konarivska, O.; Paniuk, T. Improving innovative work behavior in small and medium enterprises: Integrating transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, and psychological empowerment. Societies 2024, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, F.M. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Innovation Performance: The Mediating Effect of Employee Engagement through Leader’s Supervision. Economies 2022, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Coughlan, J. Burnout and counterproductive workplace behaviours among frontline hospitality employees: The effect of perceived contract precarity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Pádua, M.; Moreira, A.C. Leadership styles and innovation management: What is the role of human capital? Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarabiat, Y.A.; Eyupoglu, S. Is silence golden? The influence of employee silence on the transactional leadership and job satisfaction relationship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrejat, P.C. When to challenge employees’ comfort zones? The interplay between culture fit, innovation culture and supervisors’ intellectual stimulation. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Lu, J. Differential leadership and innovation performance of new generation employees: The moderating effect of self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20584–20598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A.J.S.; Colombat, P.; Ndiaye, A.; Fouquereau, E. Burnout profiles: Dimensionality, replicability, and associations with predictors and outcomes. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 4504–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, E. The effects of ethical leadership perceptions and personal characteristics on professional burnout levels of teachers. Upravlenets 2020, 11, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozinska-Pawelczyk, A. The role of innovative human resource management practices, organizational support and knowledge worker effort in counteracting job burnout in the Polish business services sector. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2024, 37, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, X. Is an academic justice climate effective? The moderation role of sensitivity and perceived organizational support on the impact of academic justice climate on innovation performance: A double-intermediary model of spiritual health system. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20096–20110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tang, C.; Xu, N.; Lai, Y. Unlocking the relationships between developmental human resource practices, psychological collectivism and knowledge hiding: The moderating role of affective organizational commitment. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2024, 37, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, S.; Brtka, E.; Poštin, J.; Ilić-Kosanović, T.; Nikolić, M. The influence of organizational culture and leadership on workplace bullying in organizations in Serbia. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2022, 27, 519–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J.; Qamar, M.; Allam, H.; Malik, S. The Impact of Innovation on economic Growth, foreign direct Investment, and Self-Employment: A Global perspective. Economies 2023, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, R.; Lewis, R.; Yarker, J.; Zernerova, L.; Flaxman, P.E. Increasing workforce psychological flexibility through organization-wide training: Influence on stress resilience, job burnout, and performance. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 33, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Xu, C.; Yu, S.; Gong, X. Research on the Impact of Challenge-Hindrance Stress on Employees’ Innovation Performance: A Chain Mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 745259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo-Ortiz, J.; González-Benito, J.; Galende, J. An analysis of the relationship between total quality management-based human resource management practices and innovation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1191–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Jimenez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Innovation and human resource management fit: An empirical study. Int. J. Manpow. 2005, 26, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, Y. The mediating effect of knowledge management on social interaction and innovation performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2009, 30, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Todor, W.D.; Grover, R.A.; Huber, V.L. Situational moderators of leader reward and punishment behaviors: Fact or fiction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 34, 21–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rich, G.A. Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS); American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Ruiz-Quintanilla, S.A.; Dorfman, P.W.; Falkus, S.A.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Cultural influences on leadership and organizations: Project Globe. In Advances in Global Leadership, 2nd ed.; Mobley, W.H., Gessner, M.J., Arnold, V., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 1999; pp. 171–233. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Javidan, M.; Hanges, P.; Dorfman, P. Understanding Cultures and Implicit Leadership Theories Across the Globe: An Introduction to Project GLOBE. J. World Bus. 2002, 37, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Leadership, Culture, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koroglu, Ş.; Ozmen, O. The mediating effect of work engagement on innovative work behavior and the role of psychological well-being in the job demands–resources (JD-R) model. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 14, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-Performance Work System, Work Well-Being, and Employee Creativity: Cross-Level Moderating role of Transformational leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Xue, M.; Zhao, J. The Association between Artificial Intelligence Awareness and Employee Depression: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Polese, A. Informal Economies in Post-Socialist Spaces; Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Smallbone, D. Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Strategies in Transition Economies: An Institutional perspective. In Small Firms and Economic Development in Developed and Transition Economies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Shamroukh, S. Predictive modeling of burnout based on organizational culture perceptions among health systems employees: A comparative study using correlation, decision tree, and Bayesian analyses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S.; Melnyk, B.M.; Hsieh, A.P.; Helsabeck, N.P.; Giuliano, K.K.; Vital, C. Innovation, wellness, and EBP cultures are associated with less burnout, better mental health, and higher job satisfaction in nurses and the healthcare workforce. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2025, 22, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saud, J.; Rice, J. Stress, Teamwork, and Wellbeing Policies: A synergistic approach to reducing burnout in public sector organizations. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Xie, M. Employee innovative behavior and workplace wellbeing: Leader support for innovation and coworker ostracism as mediators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1014195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands–Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Aravind, D. Managerial innovation: Conceptions, processes, and antecedents. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 423–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ismail, F.B.; Hussain, A.; Alghazali, B. The interplay of leadership styles, innovative work behavior, organizational culture, and organizational citizenship behavior. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, D.; Chambel, M.J.; Carvalho, V.S. Supervisor Support and Work-Family Practices: A Systematic review. Societies 2024, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pladdys, J. Mitigating workplace burnout through transformational leadership and employee participation in recovery experiences. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2024, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Park, H.; Kim, H.J. Innovation through individual-focused transformational leadership in China: Mediation by leader identification and cross-level moderation by team-focused leadership and innovation climate. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1615515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xiang, K. Transformational Leadership, Organizational resilience, and Team Innovation Performance: A model for testing moderation and mediation effects. Behav. Sci. 2024, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisser, R.; Dietrich, M.S.; Spetz, J.; Ramanujam, R.; Lauderdale, J.; Stolldorf, D.P. Psychological safety is associated with better work environment and lower levels of clinician burnout. Health Aff. Sch. 2024, 2, qxae091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Wang, J.; Tong, D.Y.K. Does power distance necessarily hinder individual innovation? A Moderated-Mediation model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Lee, J.W. Effects of hierarchical unit culture and power distance orientation on nurses’ silence behavior: The roles of perceived futility and hospital management support for patient safety. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 6564570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennouna, A.; Boughaba, A.; Djabou, S.; Mouda, M. Enhancing Workplace Well-being: Unveiling the Dynamics of Leader-Member Exchange and Worker Safety Behavior through Psychological Safety and Job Satisfaction. Saf. Health Work 2024, 16, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Varma, V.; Vijay, T.S.; Cabral, C. Technostress influence on innovative work behaviour and the mitigating effect of leader-member exchange: A moderated mediation study in the Indian banking industry. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansoy, S.U. Moderating role of leader-member exchange in the effect of innovative work behavior on turnover intention. Zb. Rad. Ekon. Fak. U Rijeci 2023, 41, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovic, M. How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 62, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmazyurek, Y.; Ocak, M. The moderating role of psychological power distance on the relationship between destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23232–23246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptulon, E.K.; Elmadani, M.; Limungi, G.M.; Simon, K.; Tóth, L.; Horvath, E.; Szőllősi, A.; Galgalo, D.A.; Maté, O.; Siket, A.U. Transforming nursing work environments: The impact of organizational culture on work-related stress among nurses: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taras, V.; Steel, P.; Kirkman, B.L. Three decades of research on national culture in the workplace. Organ. Dyn. 2011, 40, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janićijević, N. The impact of national culture on leadership. Econ. Themes 2019, 57, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y. The Relationship between Female Leadership Traits and Employee Innovation Performance-The Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Usman, M.; Yue, W.; Yasmin, F.; Sokolova, M. Leadher: Role of women leadership in shaping corporate innovation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Gao, H. Moderated mediation analysis of the relationship between inclusive leadership and innovation behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Zobi, M.A.; Altawalbeh, M.; Alim, S.A.; Lutfi, A.; Marashdeh, Z.; Al-Nohood, S.; Barrak, T.A. Female leadership and environmental innovation: Do gender boards make a difference? Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred, M.; Mukhtar-Landgren, D. Productive resistance in public sector innovation—Introducing social impact bonds in Swedish local government. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 26, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Xie, E. Symbolic or substantial? Different responses of state-owned and privately owned firms to government innovation policies. Technovation 2023, 127, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halling, A.; Baekgaard, M. Administrative Burden in Citizen–State Interactions: A Systematic Literature review. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2023, 34, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Gong, X. Digital transformation and innovation output of manufacturing companies-An analysis of the mediating role of internal and external transaction costs. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Conceptual Definition | Operational Definition (Measurement) | Scale/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | The extent to which the organization introduces new or significantly improved products and services. | Mean score of 2 items assessing changes in product/service offerings. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [84,85,86] |

| Process innovation | Introduction or improvement of methods in production, workflow, or service delivery. | Mean score of 3 items reflecting changes in internal processes. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [84,85,86] |

| Administrative innovation | Changes in organizational policies, structures, procedures or management practices. | Average score of 3 items reflecting changes in administrative systems. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [84,85,86] |

| Burnout (Work-related) | A state of emotional fatigue and reduced energy caused by prolonged job stress. | Mean score of 7 items from the work-related burnout subscale (CBI). | 7-point Likert, adapted from [87] |

| Transformational leadership | Leadership behavior that inspires, motivates and intellectually stimulates employees. | Mean score of 14 relevant subscale items. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [88,89,90,91] |

| Transactional/punitive leadership | Leadership behavior relying on control, sanctions and conditional reinforcement. | Mean score of 7 relevant subscale items. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [88,89,90,91] |

| Ethical leadership | Leader behavior that demonstrates fairness, transparency, and ethical conduct. | Mean score of 10 items from Brown et al. ethical leadership scale. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [92] |

| LMX (Leader–Member Exchange) | Quality of the relationship between leader and subordinate. | Mean score of 12 items from Liden & Maslyn LMX scale. | 7-point Likert, adapted from [93] |

| Organizational culture dimensions | Shared norms and values shaping organizational behavior. | Mean score of 16 items regarding dimensions: power distance, collectivism, human orientation, performance orientation. | 7-point Likert, GLOBE study [94,95,96] |

| Construct | Number of Items | KMO | α | AVE | CR | % Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | 2 | 0.50 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 86.2 |

| Process innovation | 3 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 87.8 |

| Administrative innovation | 3 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 88.0 |

| Burnout | 7 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 73.9 |

| Construct | √AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | 0.93 | — | |||

| Process innovation | 0.94 | 0.765 | — | ||

| Administrative innovation | 0.94 | 0.753 | 0.882 | — | |

| Burnout | 0.86 | −0.259 | −0.342 | −0.368 | — |

| Variable | Min | Max | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.37 | 1.61 | −0.456 | −0.593 |

| Process innovation | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.93 | 1.52 | −0.658 | −0.206 |

| Administrative innovation | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.10 | 1.49 | −0.782 | 0.019 |

| Burnout | 1.00 | 7.00 | 3.37 | 1.62 | 0.651 | −0.585 |

| Variables | Burnout | Product and Service Innovation | Process Innovation | Administrative Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout | 1 | −0.259 ** (p < 0.001) | −0.342 ** (p < 0.001) | −0.368 ** (p < 0.001) |

| Product and service innovation | 1 | 0.765 ** (p < 0.001) | 0.753 ** (p < 0.001) | |

| Process innovation | 1 | 0.882 ** (p < 0.001) | ||

| Administrative innovation | 1 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.372 | 0.138 | 0.132 | 1.50930 | 2.065 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 146.930 | 3 | 48.977 | 21.500 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 915.750 | 402 | 2.278 | ||

| Total | 1062.680 | 405 |

| Variable | B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 5.424 | 0.269 | 20.157 | 0.000 | |

| Product and service innovation | 0.067 | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.901 | 0.368 |

| Process innovation | −0.118 | 0.111 | −0.111 | −1.070 | 0.285 |

| Administrative innovation | −0.347 | 0.110 | −0.320 | −3.144 | 0.002 |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | 0.067 | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.901 | 0.368 | [−0.081, 0.214] |

| Process innovation | −0.118 | 0.111 | −0.111 | −1.070 | 0.285 | [−0.336, 0.099] |

| Administrative innovation | −0.347 | 0.110 | −0.320 | −3.144 | 0.002 | [−0.563, −0.130] |

| (Constant) | 5.424 | 0.269 | — | 20.157 | 0.000 | [4.895, 5.953] |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational leadership | −0.124 | 0.078 | −0.127 | −1.58 | 0.111 | [−0.277, 0.029] |

| High performance expectation | −0.166 | 0.074 | −0.138 | −2.25 | 0.026 | [−0.313, −0.020] |

| Intellectual stimulation | −0.108 | 0.079 | −0.106 | −1.36 | 0.177 | [−0.263, 0.048] |

| Rewards (incentives) | −0.218 | 0.066 | −0.231 | −3.32 | 0.001 | [−0.347, −0.089] |

| Punitive leadership behavior | 0.347 | 0.091 | 0.313 | 3.81 | 0.000 | [0.168, 0.525] |

| (Constant) | 4.944 | 0.269 | — | 18.38 | 0.000 | [4.415, 5.473] |

| Model | R | R2 | Adj. R2 | Std. Error | ∆R2 | F Change | df1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.372 | 0.138 | 0.132 | 0.93175 | 0.138 | 21.50 | 3 |

| 2 | 0.811 | 0.658 | 0.639 | 0.60108 | 0.520 | 30.68 | 19 |

| 3 | 0.918 | 0.843 | 0.805 | 0.44168 | 0.185 | 6.725 | 57 |

| Model | SS Regression | df | MS | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55.997 | 3 | 18.666 | 21.500 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 266.621 | 22 | 12.119 | 33.543 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 341.404 | 79 | 4.322 | 22.153 | 0.000 |

| Predictor (Standardized) | β | p | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | |||

| Power distance | 0.655 | <0.001 | Higher power distance is associated with higher burnout. |

| Collectivism | −0.193 | 0.029 | Greater collectivism is associated with lower burnout. |

| Transformational leadership behavior | 0.259 | 0.002 | Transformational leadership is associated with higher burnout. |

| Encouraging leadership behavior (empathy) | 0.190 | 0.004 | Empathic leadership behavior is associated with higher burnout. |

| High performance expectation | −0.128 | 0.008 | High performance expectations reduce burnout. |

| Intellectual stimulation | −0.179 | 0.016 | Intellectual stimulation reduces burnout. |

| Rewards (incentives) | −0.208 | 0.010 | Rewards reduce burnout. |

| Punitive leadership behavior | 0.292 | <0.001 | Punitive leadership increases burnout. |

| Affective attachment (LMX) | −0.288 | 0.001 | Affective attachment reduces burnout. |

| Significant interactions (moderation) | |||

| Process innovation × Power distance | 0.330 | 0.025 | The effect of process innovation is stronger at higher levels of power distance. |

| Product and service innovation × Human orientation | 0.496 | <0.001 | The effect of product and service innovation is stronger in organizations with a high human orientation. |

| Administrative innovation × Punitive leadership behavior | −0.616 | <0.001 | The protective effect of administrative innovation is weaker under a punitive leadership culture. |

| Process innovation × Intellectual stimulation | −0.729 | 0.004 | The effect of process innovation decreases when intellectual stimulation is high. |

| Administrative innovation × Intellectual stimulation | 0.879 | <0.001 | The effect of administrative innovation increases with higher intellectual stimulation. |

| Process innovation × Loyalty (LMX) | 0.461 | 0.031 | Higher loyalty within LMX is associated with greater burnout under process innovation. |

| Administrative innovation × Professional respect (LMX) | −0.625 | 0.004 | Professional respect within LMX reduces burnout under administrative innovation. |

| Administrative innovation × Loyalty (LMX) | −1.271 | <0.001 | Higher loyalty within LMX strongly reduces burnout under administrative innovation. |

| Administrative innovation × Respondent’s gender (negative) | −0.181 | 0.049 | The effect of administrative innovation is stronger among women. |

| Administrative innovation × Respondent’s gender (positive) | 0.563 | 0.003 | Administrative innovation has a more positive effect among women. |

| Administrative innovation × Supervisor’s gender | 0.647 | 0.001 | The effect of administrative innovation is stronger when the supervisor is female. |

| Administrative innovation × Ownership (public) | 0.417 | 0.043 | The effect of administrative innovation is stronger in public organizations. |

| Administrative innovation × Organization type (service) | −0.421 | 0.000 | The effect of administrative innovation is stronger in the manufacturing sector. |

| Predictor | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Product and service innovation | 0.387 | 2.582 |

| Process innovation | 0.198 | 5.042 |

| Administrative innovation | 0.207 | 4.828 |

| Ethical leadership | 0.476 | 2.102 |

| Leader–member exchange (LMX) | 0.590 | 1.695 |

| Power distance | 0.515 | 1.941 |

| Organizational culture | 0.421 | 2.374 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gluvakov, V.; Kavalić, M.; Nikolić, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Stanisavljev, S.; Mirković, S. Organizational Innovation and Managerial Burnout: Implications for Well-Being and Social Sustainability in a Transition Economy. Societies 2025, 15, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120322

Gluvakov V, Kavalić M, Nikolić M, Ćoćkalo D, Stanisavljev S, Mirković S. Organizational Innovation and Managerial Burnout: Implications for Well-Being and Social Sustainability in a Transition Economy. Societies. 2025; 15(12):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120322

Chicago/Turabian StyleGluvakov, Verica, Mila Kavalić, Milan Nikolić, Dragan Ćoćkalo, Sanja Stanisavljev, and Snežana Mirković. 2025. "Organizational Innovation and Managerial Burnout: Implications for Well-Being and Social Sustainability in a Transition Economy" Societies 15, no. 12: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120322

APA StyleGluvakov, V., Kavalić, M., Nikolić, M., Ćoćkalo, D., Stanisavljev, S., & Mirković, S. (2025). Organizational Innovation and Managerial Burnout: Implications for Well-Being and Social Sustainability in a Transition Economy. Societies, 15(12), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120322