Socio-Economic Services for Addressing Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurs in South Africa: A Multi-Sectoral Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

Xenophobic attacks resulted in 694 deaths, 5648 looted shops, and 128,849 displacements between 1994 and August 2025. In May 2008, attacks took place in at least 135 locations across the country. The perpetrators of such attacks did not target white people but rather migrants from other African countries and, to a lesser degree, from South Asian countries, whom they blamed for increased crime and the high unemployment rate in South Africa.

1.1. Xenophobia: Regional and National Trends

7072 asylum applications by refugees were received in 2024 in South Africa, according to UNHCR. Most of them came from Ethiopia, Congo (Democratic Republic of Congo), and Somalia. A total of 13,139 decisions have been made on initial applications. Around 12% of them answered positively. 88 per cent of asylum applications have been rejected in the first instance. The most successful have been the applications of refugees from Cambodia and Palestine [12].

In 2024, a total of 2,631,100 migrants lived in South Africa, representing about 4.1 per cent of the total population. These are all residents who live permanently in the country but were born in another country. The numbers include granted refugees but no asylum seekers [12].

1.2. Effects of Xenophobic Attacks

1.3. Legislative and Policy Responses to Xenophobic Attacks

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Biographical Profile of Participants

3.2. Services from the Government

The South African government did not do anything. When the police come to that side [the place he used to operate his business], they just come to investigate. We do not see any help from the Government. (Participant 3)

They did nothing, someone said, I must go ask the Government. Now it is ten years, and I have nothing. The government is not saying anything. I see nothing from anybody, money, nothing. The police said nothing. You open the case with the Government, and nothing comes up. The Government has money but does not want to help us, like now, I have been waiting for assistance for many years. (Participant 1)

You see, if I had the money, I was going to open another one. Now, if the government can give me the money, I will go and open another shop. (Participant 3)

We are waiting for the government to try something for us, not only for me, but for everyone else. Maybe money to assist each one to start the business again. Now we don’t have power, and there is no money. (Participant 7)

I think the government must educate those people to also treat us like human beings. They must not consider us like animals, where they can take everything from us just like that. (Participant 6)

The government can pass laws that state that anybody practising xenophobia is going to be in jail for ten years or eleven years. (Participant 8)

3.3. Services from the CIVIL Society Organisations

3.3.1. Community Support

You know, you people [the researcher as a South African] are not the same. There are people in South Africa who are good, you know. (Participant 1)

If I am surviving, it is because of the South African people. You see, I have left some of the family members at home, but here I am, and I have found kind, loving, and helpful people. (Participant 2)

Even from South Africans, for example, they can say: My friend, tomorrow do not go to work and take care of yourself. That is being caring. (Participant 9)

3.3.2. Spiritual Support

We also want pastors to preach about it in the pulpit in the church, anywhere, whether you are a Christian or a Muslim. We want this to spread to everybody. Maybe when the pastor is preaching inside the church, they can spread the word outside. (Participant 2)

My church is supporting me, they teach me how to survive, how to take care of my brother, and not treat him badly, and to stay good. (Participant 4)

In the church, if you have a problem, the people support you. They offer things like food, and some will offer money to take care of your family, buy things for the family. (Participant 10)

3.3.3. Support from Fellow Refugees

Like us Ethiopians, we have a group of people from Ethiopia, and we try to see that if someone needs something, we try to see how to assist them. (Participant 8)

I tried working for myself, but my friend told me: No, please come and work with me, you cannot stay at home. Even though your wife is working, come and work with me. I will give you something to eat, school, and transport. (Participant 9)

I advise my fellow refugees not to stay away from each other; everybody should stay in the township so that they are closer to their countrymen. When there are xenophobic attacks, we quickly circulate the information in our networks and say: Please don’t come to the shop today, please don’t come, people are attacking the shops. That’s what saved me that day. (Participant 5)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations of the Study

5.2. Significance and Implications of the Study

5.3. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masinga, P.; Sibanda, S.; Lelope, L.A. Xenophobic Attacks Against Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and Migrant Entrepreneurs in Atteridgeville, South Africa: A Social Identity Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murenje, M. Human Rights and Migration: Perspectives of Zimbabwean Migrants Living in Johannesburg, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dessah, M.O. Naming and exploring the causes of collective violence against African migrants in post-apartheid South Africa: Whither ubuntu? J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2015, 11, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinomona, E.; Mazariri, E.T. Examining the Phenomenon of Xenophobia as Experienced by African Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Johannesburg, South Africa: Intensifying the Spirit of Ubuntu. Int. J. Res. Bus. Stud. Manag. 2015, 2, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Orago, N.W. Socio-economic rights and the potential for structural reforms: A comparative perspective on the interpretation of the socio-economic rights in the Constitution of Kenya, 2010. In Human Rights and Democratic Governance in Kenya: A Post-2007 Appraisal; Mbondenyi, M., Asaala, E., Kabau, T., Waris, A., Eds.; Pretoria University Law Press: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage. 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Socio-Economic%20Advantage%20and%20Disadvantage~123 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Amnesty International. Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Migrants. 2025. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/whatwe-do/refugees-asylum-seekers-and-migrants/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Misago, J.P.; Freemantle, I.; Landau, L.B. Protection from Xenophobia: An Evaluation of UNHCR’s Regional Office for Southern Africa’s Xenophobia-Related Programmes; The African Centre for Migration and Society: Johannesburg, South Africa; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/research/evalreports/55cb153f9/protection-xenophobia-evaluation-unhcrs-regional-office-southern-africas.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Xenowatch. Total Number of Xenophobic Discrimination Incidents in South Africa from 1994. 2025. Available online: https://www.xenowatch.ac.za/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Mabera, F. The impact of xenophobia and xenophobic violence on South Africa’s developmental partnership agenda. Afr. Rev. 2017, 9, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, S.; Sambo, J.; Dahal, S. Social Service Providers’ Understanding of the Consequences of Human Trafficking on Women Survivors—A South African Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Data. Asylum Applications and Refugees in South Africa. 2025. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/africa/south-africa/asylum.php (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Fourchard, L.; Segatti, A. Xenophobic Violence and the Manufacture of Difference in Africa: Introduction to the Focus Section. Int.J. Confl. Violence 2015, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oyelana, A.A. Effects of xenophobic attacks on the economic development of South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 46, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Broadcasting Corporation. ‘No Cause for Alarm’—Ghana and Nigeria Foreign Ministers Meet over Protest Against Nigerians. 2025. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/articles/czjm78x7jx9o (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Mutanda, D. Xenophobic violence in South Africa: Mirroring economic and political development failures in Africa. Afr. Identities. 2017, 15, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafukata, M.A. Xenophobia—The evil story of the beginnings of fascism in post-apartheid South Africa. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2015, 3, 30–44. Available online: https://internationaljournalcorner.com/index.php/theijhss/article/view/126069 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Tshishonga, N. The impact of xenophobia-Afrophobia on the informal economy in Durban CBD, South Africa. J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2015, 11, 163–179. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC185069 (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dratwa, B. Xenophobia: A Pervasive Crisis in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Georget. J. Int. Aff. 2024. Available online: https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2024/05/26/xenophobia-a-pervasive-crisis-in-post-apartheid-south-africa/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Democratic Alliance. DA Calls for Urgent Public Order Police to Stop Operation Dudula’s Xenophobic Presence at Health Facilities. 2025. Available online: https://www.da.org.za/2025/08/da-calls-for-urgent-public-order-police-to-stop-operationdudulas-xenophobic-presence-at-health-facilities (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- The Star. Operation Dudula Under Fire for Campaign to Ban Foreign Children from Public Schools in 2026. 2025. Available online: https://thestar.co.za/news/south-africa/2025-08-01-operation-dudula-under-fire-for-campaign-to-ban-foreign-childrenfrom-public-schools-in-2026/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Parliament of the Republic of South Africa. Media Statement: Operation Dudula Is a Distraction from the Work of Government. 2025. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/press-releases/media-statement-operation-dudula-distraction-workgovernment (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Lelope, L.A. The Socio-Economic Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Refugee Entrepreneurs in Atteridgeville; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, A.; The Impact of Xenophobia on Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Africa. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR). Available online: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2013CrimeConfXenophopia.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Steinhardt, M.F. The Impact of Xenophobic Violence on the Integration of Immigrants; (No. 11781); IZA Discussion Papers; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://docs.iza.org/dp11781.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Vrsanska, I.; Kavicky, V.; Jangl, S. Xenophobia—The cause of terrorism in a democratic society. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 168–171. Available online: https://www.ijhssnet.com/journal/index/3826 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chekenya, N.S. Migrants and xenophobic attacks in South Africa: Theory and evidence. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2024, 00219096241287369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Essa, A. No Place Like Home: Xenophobia in South Africa. 2015. Available online: https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2015/XenophobiaSouthAfrica/index.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Mokoena, S.K. Local economic development in South Africa: Reflections on foreign nationals’ informal businesses. In Proceedings of the SAAPAM 4th Annual Conference Proceedings-Limpopo, Limpopo, South Africa, 28–30 October 2015; 2015; Volume 2, pp. 102–115. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Edwin-Mutyenyoka/publication/291295431_POSTAPARTHEID_GOVERNANCE_MEASURING_THE_INCEDENCE_OF_URBAN_POVERTY_IN_POLOKWANE_CITY/links/569f560008ae21a56425dd03/POST-APARTHEID-GOVERNANCE-MEASURING-THE-INCEDENCE-OF-URBAN-POVERTY-INPOLOKWANE-CITY.pdf#page=109 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Adebisi, A.P. Xenophobia: Healing a festering sore in Nigerian-South African relations. J. Int. Relat. Foreign Policy 2017, 5, 83–92. Available online: https://jirfp.thebrpi.org/vol-5-no-1-june-2017-abstract-6-jirfp (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Afrika, M. ‘Stop Xenophobia or Else’, Students Warn. Sunday Times, 26 February 2017; p. 4. Available online: https://www.sundaytimes.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/news/2017-02-26-xenophobic-attacks-stop-xenophobia-or-else-students-warn/#google_vignette (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Matthee, M.; Krugell, W.; Mzumara, M. Microeconomic competitiveness and post-conflict reconstruction: Firm-level evidence from Zimbabwe. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 14, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzanani, T. A thematic analysis of newspaper articles on xenophobia and tourism in South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Act. Health Sci. 2016, 22, 335–343. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC187474 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Niyitunga, E.B. Xenophobia: A hindrance factor to South Africa’s ambition of becoming a developmental state. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2024, 6, 1337423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Perks, S. The influence of the political climate on South Africa’s tourism industry. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Academic Research Conference in London-Zurich, London, UK, 7–8 November 2016; Volume 1, pp. 263–286. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305984577_the_influence_of_the_political_climate_on_south_africa’s_tourism_industry (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Sibanda, S. Components of a holistic family reunification services model for children in alternative care: A South African perspective. Afr. J. Soc. Work 2025, 15, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Immigration and economic growth. In How Immigrants Contribute to Developing Countries’ Economies; ILO, Geneva/OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rilley, K. The role of law in curbing xenophobia. De Rebus 2015, 557, 18–19. Available online: https://www.saflii.org/za/journals/DEREBUS/2015/180.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Koskimaki, L.; Mazani, P. Migrant and refugee solidarity in urban South Africa. In Urban Migrant Inclusion and Refugee Protection—Volume 2: Global Perspectives of Sanctuary, Solidarity, and Hospitality; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Atteridgeville. 2025. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=4286&id=11387 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chikohomero, R. Understanding Conflict Between Locals and Migrants in South Africa: Case Studies in Atteridgeville and Diepsloot; Institute of Security Studies: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023; Available online: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar-55-rev.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sobočan, A.M.; Bertotti, T.; Strom-Gottfried, K. Ethical considerations in social work research. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2018, 22, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madue, S.M. South Africa’s foreign and migration policies missteps: Fuels of xenophobic eruptions? J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2015, 11, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van der Westhuizen, M. Social work services to victims of xenophobia. Soc. Work/Maatskaplike Werk 2015, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub-Bernasconi, S. SocialWork and Human Rights-Linking to traditions of human rights in social work. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work. 2016, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

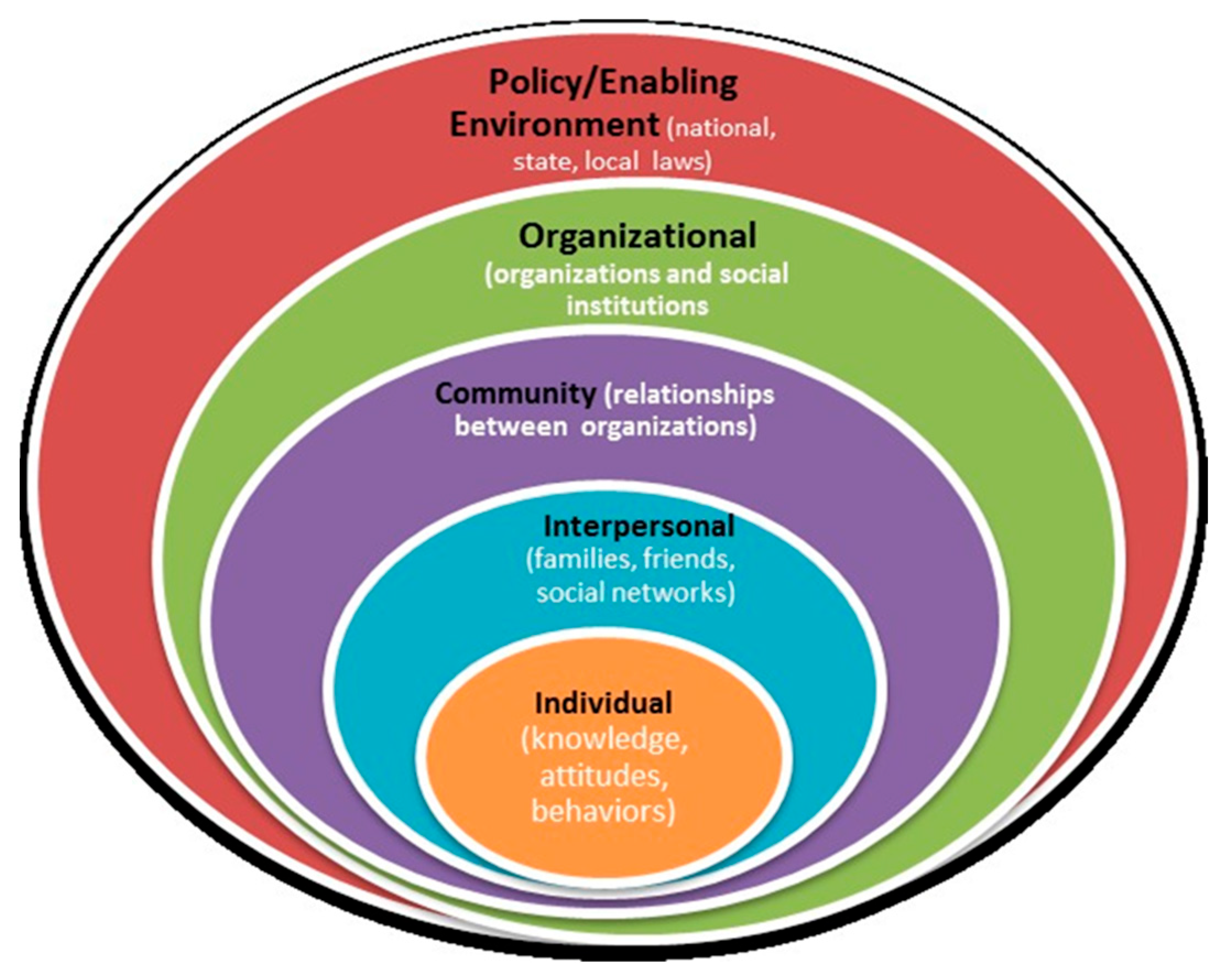

- Masinga, P.; Sibanda, S. Measures to address and prevent school-based violence in South Africa: An ecological systems perspective. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, S.; Masinga, P. A child protection issue: Exploring the causes of school-based violence in South Africa from a bioecological systems perspective. Child Prot. Pract. 2025, 5, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, J.; Sibanda, S. Multi-disciplinary initiatives for rendering services to women survivors of human trafficking in South Africa. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Council for Social Service Professions. The e-Bulletin. 2018. Available online: https://www.sacssp.co.za/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwenyango, H. The place of social work in improving access to health services among refugees: A case study of Nakivalesettlement, Uganda. Int. Soc. Work 2022, 65, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trummer, U.; Ali, T.; Mosca, D.; Mukuruva, B.; Mwenyango, H.; Novak-Zezula, S. Climate change aggravating migration and health issues in the African context: The views and direct experiences of a community of interest in the field. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant | Age | Nationality | Number of Years in Atteridgeville | Type of Business |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | Ethiopian | 7 | Spaza shop |

| 2 | 40 | Nigerian | 5 | Spaza shop |

| 3 | 35 | Burundian | 7 | Spaza shop |

| 4 | 38 | Ethiopian | 7 | Spaza shop |

| 5 | 36 | Nigerian | 7 | Spaza shop |

| 6 | 35 | Ethiopian | 10 | Spaza shop |

| 7 | 40 | Congolese | 9 | Spaza shop |

| 8 | 45 | Ethiopian | 8 | Spaza shop |

| 9 | 38 | Congolese | 8 | Spaza shop |

| 10 | 35 | Ethiopian | 6 | Spaza shop |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sibanda, S.; Murenje, M.; Masinga, P.; Lelope, L.A. Socio-Economic Services for Addressing Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurs in South Africa: A Multi-Sectoral Perspective. Societies 2025, 15, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120321

Sibanda S, Murenje M, Masinga P, Lelope LA. Socio-Economic Services for Addressing Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurs in South Africa: A Multi-Sectoral Perspective. Societies. 2025; 15(12):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120321

Chicago/Turabian StyleSibanda, Sipho, Mutsa Murenje, Poppy Masinga, and Lekopo Alinah Lelope. 2025. "Socio-Economic Services for Addressing Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurs in South Africa: A Multi-Sectoral Perspective" Societies 15, no. 12: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120321

APA StyleSibanda, S., Murenje, M., Masinga, P., & Lelope, L. A. (2025). Socio-Economic Services for Addressing Effects of Xenophobic Attacks on Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurs in South Africa: A Multi-Sectoral Perspective. Societies, 15(12), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120321