Generativity and Psychological Well-Being in Primary and Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

- (a)

- Generativity/Generatividad.

- (b)

- Psychological well-being/Ryff scale.

- (c)

- Teachers/Educators/Docentes.

- (d)

- Primary education/Secondary education/Enseñanza básica/Enseñanza secundaria.

- (e)

- Urban/Rural/Urban/Rural.

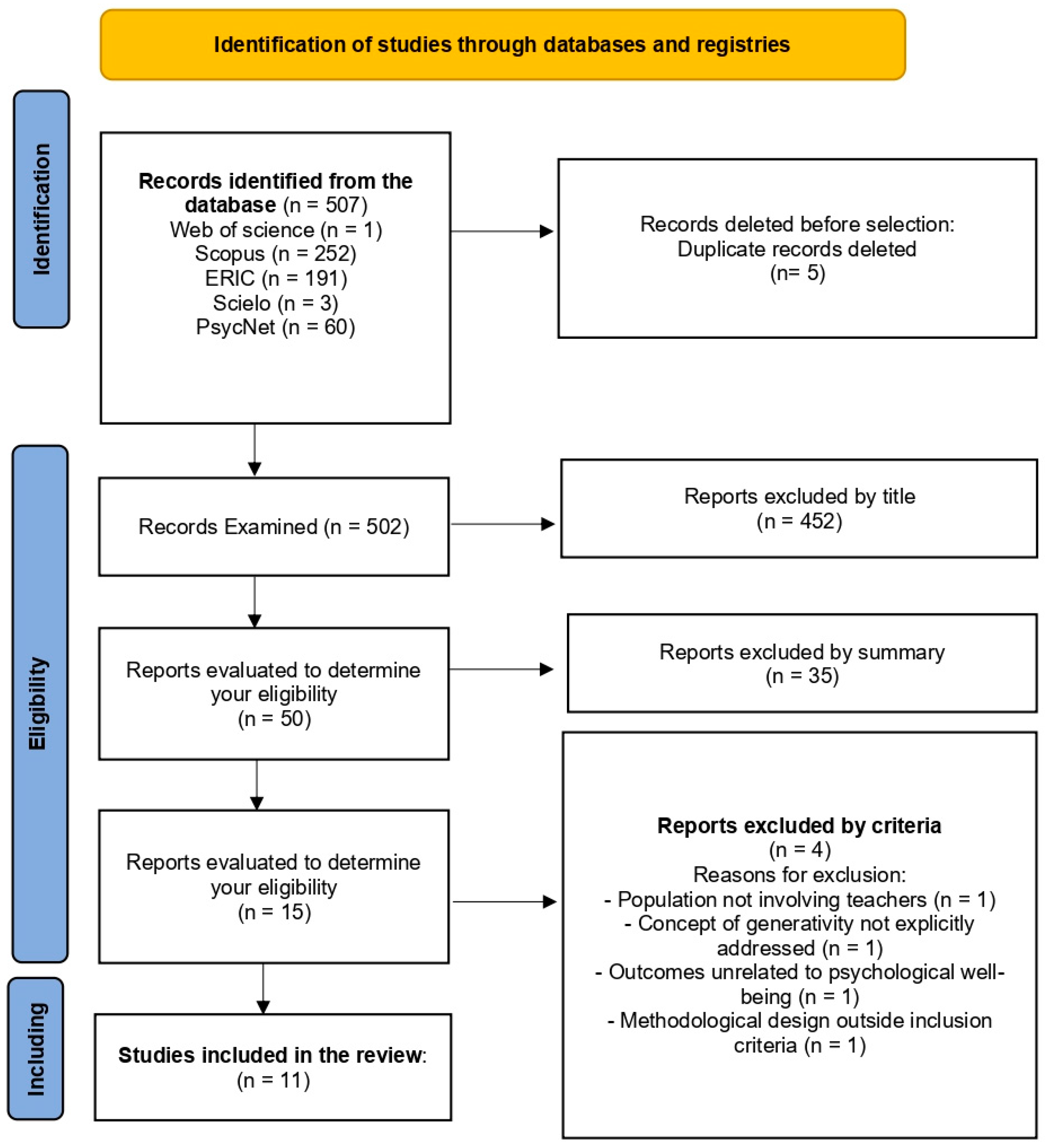

2.3. Study Selection Procedure

- (a)

- Identification: The records retrieved in each database will be exported to a bibliographic manager (Zotero or EndNote), where duplicates will be eliminated.

- (b)

- Initial screening: Two independent review authors will analyse titles and abstracts to rule out irrelevant studies.

- (c)

- Eligibility assessment: The pre-selected articles will be read in full by two independent reviewers (C.B-O. and L.C-A.), who strictly applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process involved a re-examination of the article in question against the eligibility criteria, followed by discussion until agreement was reached. For any persisting discrepancies, a third senior reviewer (E.S-O.) was consulted to make a final determination.

- (d)

- Final inclusion: Studies that meet all criteria will be incorporated into the analysis and recorded in a data extraction matrix that will include information on: authors, year of publication, country, context (urban/rural), educational level, methodological design, instruments used and main findings.

2.4. Evaluation of the Scientific Quality of Selected Articles

2.5. Synthesis and Analysis of Information

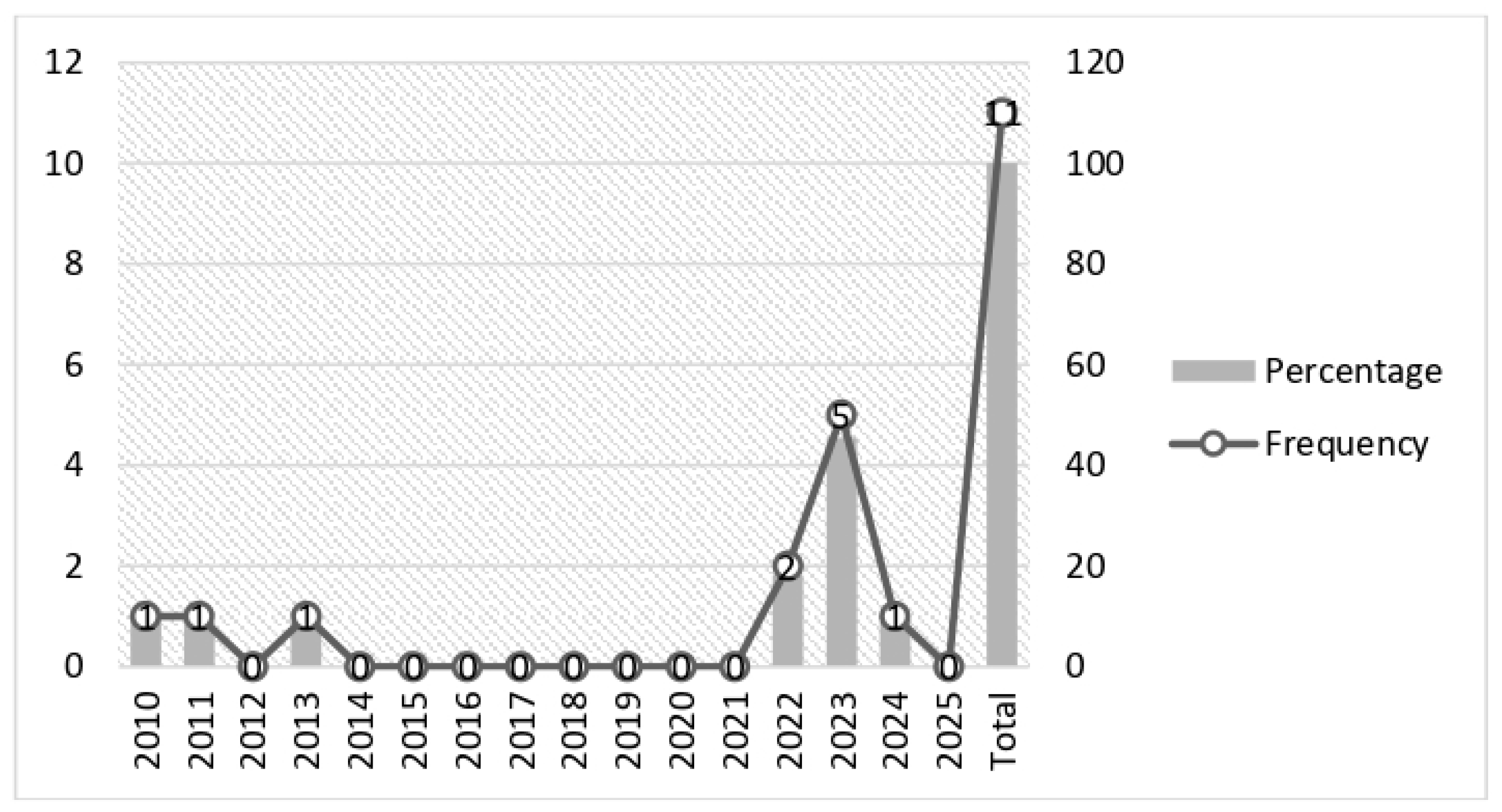

3. Results

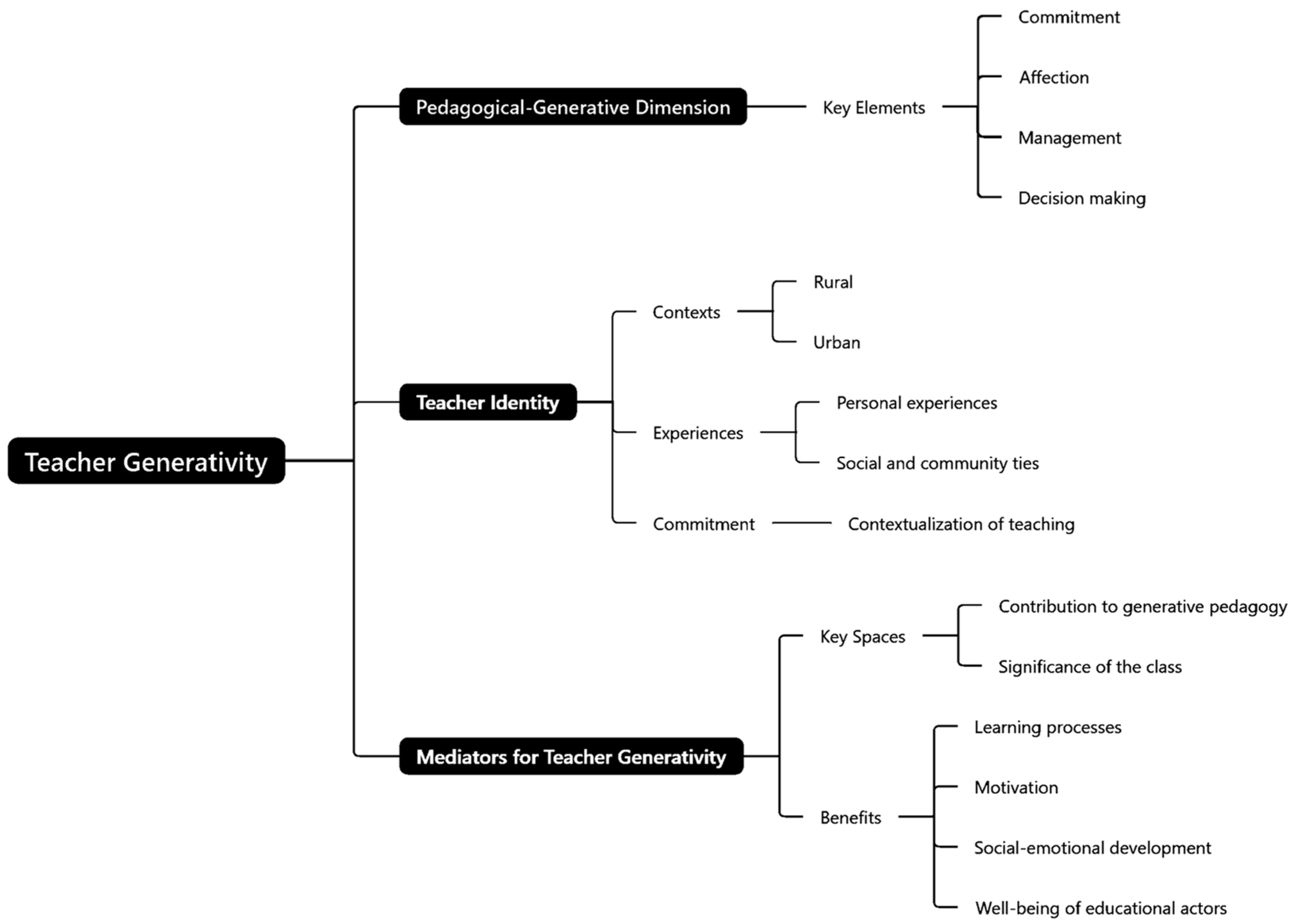

3.1. Pedagogical–Generative Dimension

3.2. Rural/Urban Teacher Identity

3.3. Mediators for Teacher Generativity

3.4. Scientific Quality Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Strategy | Total | Fecha |

| Web of Science (WOS) | TS = (“generativity” OR “teacher generativity” OR “generative concern” OR “generative behavior”) AND TS = (teacher * OR “school teacher *” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “secondary school” OR “high school”) AND TS = (“psychological well-being” OR wellbeing) AND TS = (urban OR rural OR “urban school *” OR “rural school *”) | 1 result | 3 September 2025 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“generativity” OR “teacher generativity” OR “generative concern” OR “generative behavior”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(teacher * OR “school teacher *” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “secondary school” OR “high school”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“psychological well-being” OR wellbeing) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(urban OR rural OR “urban school *” OR “rural school *”) | 252 results | 3 September 2025 |

| ERIC | (“generativity” OR “teacher generativity” OR “generative concern” OR “generative behavior”) AND (teacher * OR “school teacher *” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “secondary school” OR “high school”) AND (“psychological well-being” OR wellbeing) AND (urban OR rural OR “urban school *” OR “rural school *”) | 191 results | 3 September 2025 |

| SciELO | (“generativity” OR “teacher generativity” OR “generative concern” OR “generative behavior”) AND (teacher OR teachers OR “school teacher” OR “school teachers” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “secondary school” OR “high school”) AND (“psychological well-being” OR wellbeing) AND (urban OR rural OR “urban school” OR “urban schools”) | 3 results | 3 September 2025 |

| PsycNet (APA PsycInfo) | (“generativity” OR “teacher generativity” OR “generative concern” OR “generative behavior”) AND (teacher * OR “school teacher *” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “secondary school” OR “high school”) AND (“psychological well-being” OR wellbeing) AND (urban OR rural OR “urban school *” OR “rural school *”) | 60 results | 3 September 2025 |

References

- Masoom, M.R. Teachers’ perception of their work environment: Evidence from the primary and secondary schools of Bangladesh. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 4787558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryakova, G.; Kozhuharova, D. The Digital Competences Necessary for the Successful Pedagogical Practice of Teachers in the Digital Age. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.N.; Condes Moreno, E.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yañez-Sepulveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Navigating the New Normal: Adapting Online and Distance Learning in the Post-Pandemic Era. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Exploring the impact of workload, organizational support, and work engagement on teachers’ psychological wellbeing: A structural equation modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1345740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society, 2nd ed.; Original Work Published 1950; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P.; de St Aubin, E. A theory of generativity and its assessment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F.; Serrat, R.; Pratt, M. Generativity across the lifespan: Implications for education and social participation. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 60, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccoli, B.; Sestino, A.; Gastaldi, F.; Corso, L. The impact of autonomy and temporal flexibility on individuals’ psychological well-being in remote settings. Sinergie—Ital. J. Manag. 2022, 40. Available online: https://ojs.sijm.it/index.php/sinergie/article/view/1220 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Zacarés, J.J. Generativity in teachers: Commitment and professional meaning. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 2020, 26, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M.; Klusmann, U.; Baumert, J.; Richter, D.; Voss, T.; Hachfeld, A. Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. Respuesta a Margolis, Hodge y Alexandrou: Representaciones erróneas de la resiliencia y la esperanza docente. J. Educ. Teach. 2014, 40, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L.E.; Asbury, K. ‘Como si te hubieran quitado la alfombra de debajo de los pies’: El impacto de la COVID-19 en el profesorado de Inglaterra durante las primeras seis semanas del confinamiento en el Reino Unido. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 90, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Waber, J. Teacher Well-Being: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature from the Year 2000–2019. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative identity and generativity: New directions. J. Personal. 2021, 89, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, E.; Tobón, S.; Juárez-Hernández, L.G. Escala para Evaluar Artículos Científicos en Ciencias Sociales y Humanas- EACSH. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2019, 17, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Ramirez Jimenez, M.S. Sentido de vida y generatividad en profesores rurales chilenos. Cauriensia. Rev. Anu. Cienc. Eclesiásticas 2024, 18, 805–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Peña-Troncoso, S. Dimensiones pedagógicas de un desarrollo potencialmente generativo en profesores rurales chilenos. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2023, 89, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, J.; Dyer, E.B. Pedagogical sensemaking during side-by-side coaching: Examining the in-the-moment discursive reasoning of a teacher and coach. J. Learn. Sci. 2023, 32, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.E.; Pareja-Arellano, N.; Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Riquelme-Brevis, H. What do we know about rural teaching identity? An exploratory study based on the generative-narrative approach. J. Pedagog. 2023, 14, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Henao, S.; Huanquilén Ancan, E.; Sandoval-Obando, E.; Carter-Thuillier, B. Generativity and Rural Teacher Identity in a Mapuche Community of Toltén (Chile): An Exploratory Study. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2023, 23, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Riquelme-Brevis, H. ¿Es posible una pedagogía generativa?: Experiencias y saberes de docentes situados en la ruralidad chilena. Rev. Psicol. 2023, 32, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Calvo Muñoz, C. La propensión a la docencia en educadores rurales chilenos y sus implicaciones potencialmente generativas: Un estudio exploratorio. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2022, 22, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.E.; Calvo Muñoz, C.M. Generativity and propensity to teach in Chilean rural educators: Educational knowledge from the narrative-generative perspective. Innovaciones Educ. 2022, 24, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.J.; Cordier, R.; Wilson Whatley, L. Older male mentors’ perceptions of a Men’s Shed intergenerational mentoring program. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2013, 60, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerrett, A. Un caso de generatividad en un aula de lengua y literatura inglesa cultural y lingüísticamente compleja. Chang. Engl. 2011, 18, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesz, T. Chasms and bridges: Generativity in the space between educators’ communities of practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Domínguez, C.E.; Laborín Álvarez, J.F.; Cáñez Cota, L.A. Generativity and quality of life in rural educators: A scoping review of the evidence in comparison with work and altruistic contexts. Ann. Psychol. 2025, 41, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Bellucci, D. Generativity, aging and subjective well-being. Int. Rev. Econ. 2021, 68, 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marujo, H.Á. The nexus between peace and mental well-being: Contributions for public happiness. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2023, 27, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.Y.; Lam, C.B.; Chung, K.K.H. Self-compassion mediates the associations of mindfulness with physical, psychological, and occupational well-being among Chinese kindergarten teachers. Early Child. Educ. J. 2024, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. Reconceptualizing effective professional development for teachers: Shifting from causal chains and generativity to complexity and employee-centrism. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, G.; Grazioplene, R.; Florence, A.; Hammer, P.; Funaro, M.C.; Davidson, L.; Bellamy, C.D. Generativity among persons providing or receiving peer or mutual support: A scoping review. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2022, 45, 123–135. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2021-91683-001 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Pareja Arellano, N.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Riquelme-Brevis, H.; Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Rivas-Valenzuela, J. Understanding the relational dynamics of chilean rural teachers: Contributions from a narrative-generative perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Griffiths, M.; Goodyear, V.; Jung, H.; Son, H.; Lee, U.; Choi, E. Influence of a professional development programme on the life skills teaching practices of secondary PE teachers. Sport Educ. Soc. 2023, 28, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F.; Lawford, H.L. Education and the Promotion of Generativity throughout Adulthood. In The Development of Generativity across Adulthood; Villar, F., Lawford, H., Pratt, M., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2024; p. 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promnitz, K.M. The Changing Role of Secondary Educators: Teacher Preparation and Social-Emotional Learning. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, D.J. Meaning in Life, Generativity and Legacy in Educational Leaders. Doctoral Dissertation, Dallas Baptist University, Dallas, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Smith, L.; Franco, M.P.; Bottiani, J.H. “We’re Teachers Right, We’re Not Social Workers?” Teacher perspectives on student mental health in a Tribal School. Sch. Ment. Health 2023, 15, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N.C.; Morin, L.E.; Gómez, L.R.; Jones, B.; Bettini, E.; Cumming, M.M.; Garwood, J.D.; Ruble, L.A. Burnout and Occupational Wellbeing of Special Education Teachers: Recent Research Synthesized. Rev. Educ. Res. 2025, 20, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, S. (Ed.) Metacognition and Education: Future Trends; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luppi, E. Exploring contemporary challenges of intergenerational education in lifelong learning societies: An introduction. Ricerche di Pedagogia e Didattica. J. Theor. Res. Educ. 2023, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throop-Robinson, E.; McKee, L. Adapting Mathematics Curriculum-Making: Lessons Learned from/with Elementary Preservice Teachers for Curriculum Research. Brock Educ. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2024, 33, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | The target population comprises primary and secondary school teachers, who are most directly engaged in teaching–learning processes at the school level. This focus is justified because teaching is a profession characterized by high psychosocial demands, with attendant risks of emotional exhaustion and declines in subjective well-being. It is also a population in which generativity finds a particularly salient expression, given the inherently intergenerational nature of teachers’ professional practice [7,10]. Restricting the review to primary and secondary teachers avoids including university or preschool personnel, whose demands and life-course experiences may differ substantially. |

| Exhibition/Concept | The conceptual focus of this review centers on two core constructs: generativity and psychological well-being. Generativity, rooted in [5] psychosocial theory and elaborated by [6], refers to concerns and actions oriented toward caring for and guiding future generations. Among teachers, it is expressed through the transmission of knowledge and values and a sustained commitment to students’ development. Psychological well-being, in turn, as defined by [8], offers a positive conception of mental health that integrates dimensions such as purpose in life, self-acceptance, and positive relations. By concentrating on these constructs, the review aims to elucidate how transcendent motivations intersect with states of positive mental health in teaching practice. |

| Background (C) | The contextual scope comprises the urban and rural environments in which teaching practice unfolds. This dimension is crucial, as the literature indicates that structural, cultural, and socioeducational conditions differ markedly across these settings, shaping teachers’ professional and personal experiences in distinct ways [15]. Teachers in rural areas often face greater shortages of material resources and heightened professional isolation, whereas those in urban environments contend with challenges stemming from overcrowding, cultural diversity, and evaluative pressures. Making context explicit helps prevent unwarranted generalizations and enables a more situated understanding of the relationship between generativity and psychological well-being. |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Author/Year | Country | Title | Type of Study | Population (N, Age, % Female) | Years of Experience | Assessment Instruments | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Chile | Sentido de vida y generatividad en profesores rurales chilenos | Qualitative interpretative; descriptive-exploratory cross-sectional | N = 12 Age = 60 years % women = 41.7% | 33 years | Generativity was explored through these narratives of personal and professional experiences, in which topics such as mentoring, contributions to the community, care of others, and teaching legacy were investigated. Social welfare was addressed in connection with the meaning of life, spirituality and the teaching function in rural areas, interpreted from the narratives. | Chilean rural teachers manifested high levels of generativity, expressed in autonomy, mentoring, pedagogical flexibility, commitment to the community, and construction of an educational legacy. In the field of social welfare, the narratives reflected community cohesion, resilience in the face of adversity, and satisfaction derived from contributing to the development of rural communities. |

| [23] | Chile | Dimensiones pedagógicas de un desarrollo potencialmente generativo en profesores rurales chilenos | Qualitative (phenomenological) | N = 12 Age = 50 years % women = 41.7% | 33 years | Life stories from the generative narrative perspective: three in-depth interviews were conducted with each teacher, to explore significant experiences, processes of construction of the narrative self and life and professional trajectories. | Rural teachers reported high levels of generativity, expressed in mentoring, pedagogical autonomy, community commitment, and building an educational legacy. In the field of social welfare, the narratives reflected community cohesion, resilience in the face of adversity and satisfaction linked to the educational contribution in rural contexts. |

| [24] | United States | Pedagogical Sensemaking during Side-by-Side Coaching: Examining the In-the-Moment Discursive Reasoning of a Teacher and Coach | Exploratory Case Study | N = 1 Age= Not reported % female= 100% | Not reported | Recordings/video and discourse analysis in classroom interaction. | Co-teaching enables real-time generative pedagogical sensemaking at three ‘altitudes’ of conversation (within, through, and beyond moments). Brief, cumulative interactions also provide opportunities for pedagogical generativity. |

| [25] | Chile | What do we know about rural teaching identity? An exploratory study based on the generative-narrative approach | Qualitative interpretative; exploratory cross-sectional Non-experimental | N = 18 Age = 60 years % women = 50% | 33 years | In-depth interviews (life-history/biographical accounts) designed from the narrative-generative perspective (based on Kvale, McAdams and McLean) and qualitative analysis of the narratives to identify generative behaviors and actions. Four categories related to generativity were identified: (1) significant life experiences; (2) pedagogical dimensions of generative development; (3) expansive-generative adulthood; (4) Personal training. | The narratives of rural teachers presented generative behaviors and actions linked to life experiences, pedagogical adaptation, commitment to future generations, and personal training; in addition, they indicated qualitative social well-being through satisfaction, positive affect, and resilience. |

| [26] | Chile | Generativity and Rural Teacher Identity in a Mapuche Community of Toltén (Chile): An Exploratory Study | Qualitative interpretative; exploratory-descriptive cross-sectional | N = 4 Age = 50 years % women = Not reported | Not reported | In-depth interviews +Nütram (Mapuche conversation). Well-being was interpreted qualitatively in the narratives through community values (respect, love, justice, belonging, interculturality). | The faculty developed a generative integrity linked to life experiences and community values through the promotion of Mapuche belonging and identity, integrating local knowledge and ancestral authorities in teaching-learning processes. |

| [27] | Chile | ¿Es posible una pedagogía generativa?: Experiencias y saberes de docentes situados en la ruralidad chilena | Qualitative; descriptive-exploratory cross-sectional | N = 12 Age = 60 years % women = 41.7% | 33 years | In-depth interviews (life history, generative narrative) and social well-being were interpreted through stories about community ties, teacher engagement and historical-cultural relevance. | Rural teachers showed a strong generative identity based on the transmission of practical knowledge, community values and historical-cultural relevance. The well-being of teachers was related to the sense of belonging and the recognition of their pedagogical practices by the community. |

| [28] | Chile | The Propensity to Teach in Chilean Rural Educators and its Potentially Generative Implications: An Exploratory Study | Qualitative interpretative; descriptive-exploratory cross-sectional | N = 12 Age = 60 years % women = 41.7% | 33 years | In-depth interviews (life stories from the narrative-generative perspective). The stories were subjected to a content analysis, following the logic of grounded theory. | The rural teachers studied show potentially generative pedagogical practices and criteria, highlighting the commitment to educational work, positive affection and flexibility in the relationship with students, favoring the construction of relevant learning with historical-sociocultural relevance for students and their communities of origin. |

| [29] | Chile | Generatividad y propensión a enseñar en educadores rurales chilenos: saberes educativos desde la perspectiva narrativa- generativa | Qualitative interpretative; descriptive-exploratory cross-sectional | N = 12 Age = 60 years % women = 41.7% | 33 years | In-depth interviews and life stories from the generative narrative perspective. The stories were subjected to a content analysis, following the logic of grounded theory. | Rural teachers exhibited potentially generative practices based on commitment, affection and flexibility, strengthening bonds with students and generating culturally relevant learning, emerging dimensions of mentoring, community leadership, collaboration, empathy and responsibility. As for social welfare. Positive implications were reported in terms of satisfaction, motivation, and sense of educational legacy. |

| [30] | Australia | Older male mentors’ perceptions of a Men’s Shed intergenerational mentoring program | Exploratory qualitative study | N = 6 Age = 65 years % women = 0% | Not reported | Individual interviews with teachers (pre- and post-project, Focus Group) and qualitative analysis of the mentors’ perceptions. | The teachers expressed a reconnection with traditional values such as sharing experience, respect, tradition, and “transmission” of knowledge through the construction project shared with young students, facilitating a generational bridge through these generative practices. |

| [31] | United States | A Case of Generativity in a Culturally and Linguistically Complex English Language Arts Classroom | Qualitative Case Study-Interpretive Approach | N = 1 Age = Not reported % female = 100% | Not reported | Semi-structured interviews using Ball’s generativity theory and analysis of the teacher’s conceptions, her discourse, curricular practices. | The interviewed teacher conceives her role as a translator and mediator of linguistic and cultural competencies, adapting her teaching style to the origins of the students. According to Ball’s theory, generativity occurs when the teacher promotes innovation based on her understanding of linguistic diversity, assumes professional responsibility to respond to emerging needs, and reflects on her own role as a teacher. |

| [32] | United States | Chasms and Bridges: Generativity in the Space between Educators’ Communities of Practice | Qualitative ethnographic study | N = Not reported Age = Not reported % female = Not reported | Not reported | The study analyzes qualitative data obtained through interviews, observations, analysis of practices and reflections, to understand how generativity processes are manifested in the professional life of educators. Any notion of well-being stems from narratives linked to meaning, identity, and teaching agency. | Generativity in this study includes a sense of responsibility, sharing professional knowledge among peers, reinterpretation of local practices, and critical reflection on what it is to teach, reform, and improve within school contexts. ‘Multi-membership’ and bridges between communities of practice promote generative change in education. |

| Author | [22] | [23] | [24] | [25] | [26] | [27] | [28] | [29] | [30] | [31] | [32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITEM I | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM II | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM III | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| ITEM IV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM V | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM VI | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| ITEM VII | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM VIII | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ITEM IX | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM X | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ITEM XI | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ITEM XII | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XIII | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XIV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XVI | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XVII | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XVIII | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ITEM XIX | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ITEM XX | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ITEM XXI | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 92/105 | 93/105 | 93/105 | 92/105 | 93/105 | 92/105 | 92/105 | 92/105 | 94/105 | 96/105 | 95/105 |

| Percentage | 88% | 89% | 89% | 88% | 89% | 88% | 88% | 88% | 89% | 91% | 90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandoval-Obando, E.; Barros-Osorio, C.; Castellanos-Alvarenga, L.; Villalta Paucar, M.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Generativity and Psychological Well-Being in Primary and Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review. Societies 2025, 15, 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110320

Sandoval-Obando E, Barros-Osorio C, Castellanos-Alvarenga L, Villalta Paucar M, Vega-Muñoz A. Generativity and Psychological Well-Being in Primary and Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review. Societies. 2025; 15(11):320. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110320

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandoval-Obando, Eduardo, Cristián Barros-Osorio, Luis Castellanos-Alvarenga, Marco Villalta Paucar, and Alejandro Vega-Muñoz. 2025. "Generativity and Psychological Well-Being in Primary and Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review" Societies 15, no. 11: 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110320

APA StyleSandoval-Obando, E., Barros-Osorio, C., Castellanos-Alvarenga, L., Villalta Paucar, M., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2025). Generativity and Psychological Well-Being in Primary and Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review. Societies, 15(11), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110320