Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to Public Perceptions of Water Scarcity during El Niño: A Case Study of Santa Marta, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

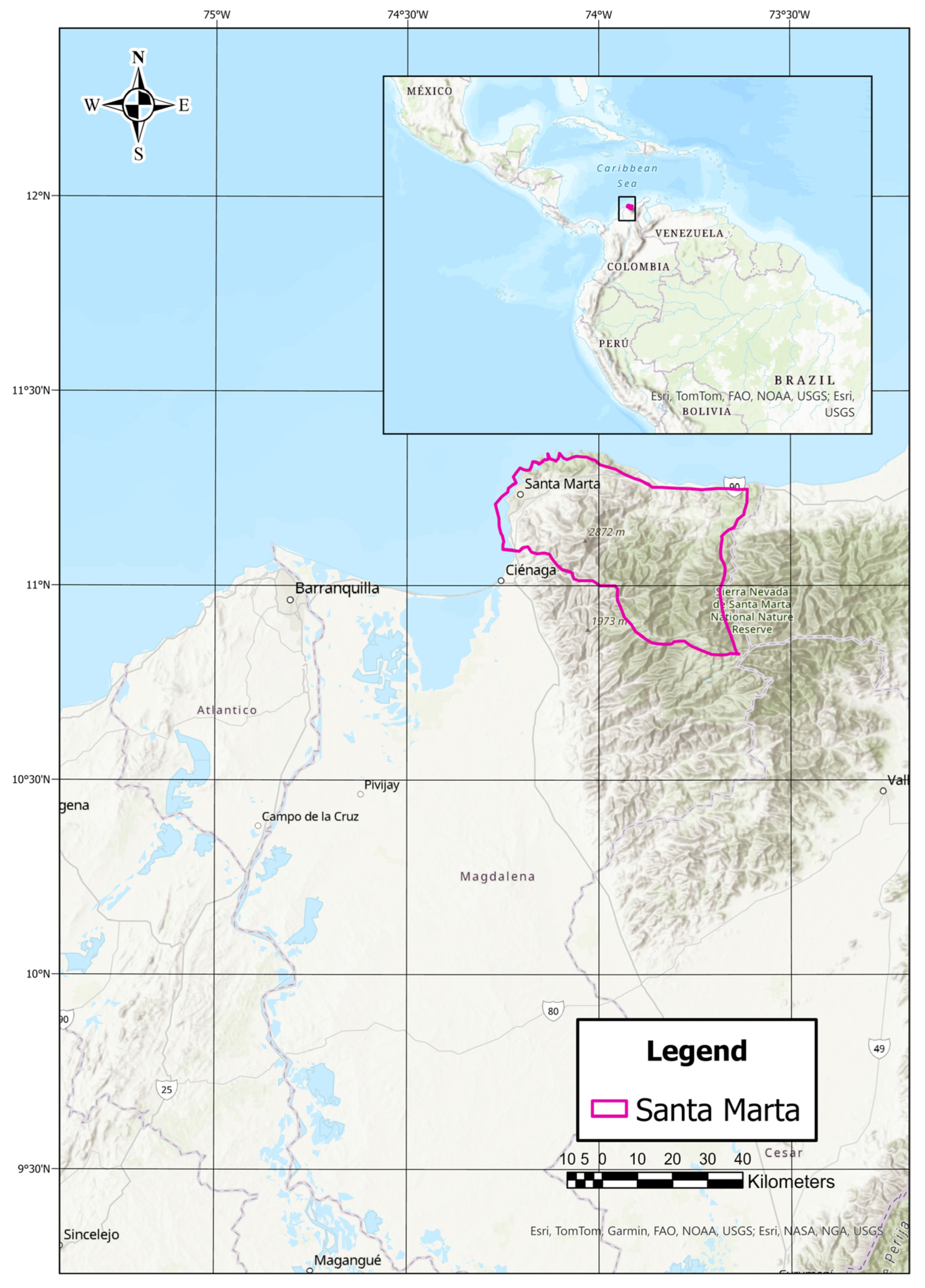

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

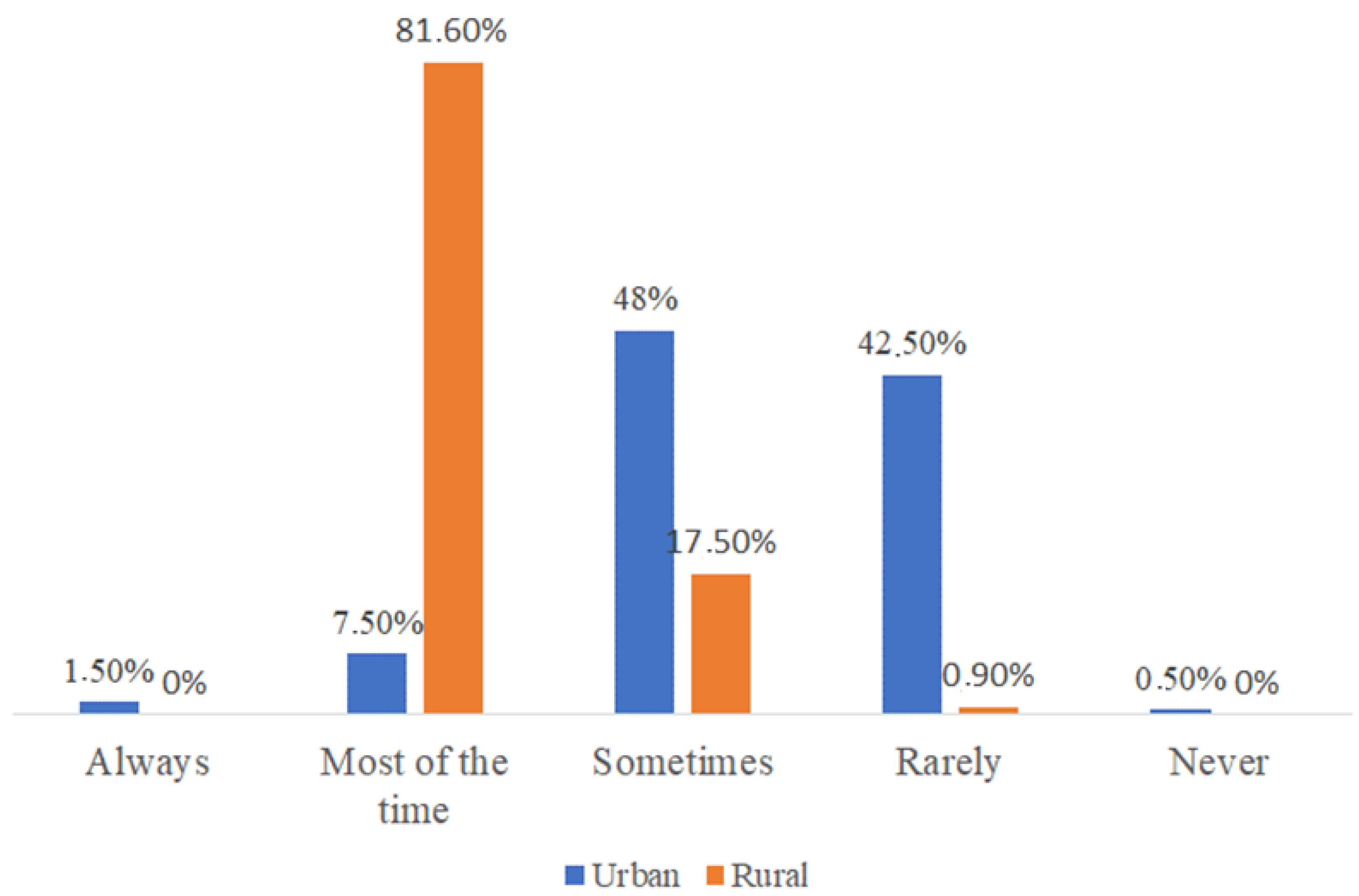

4.1. Water Scarcity Perception

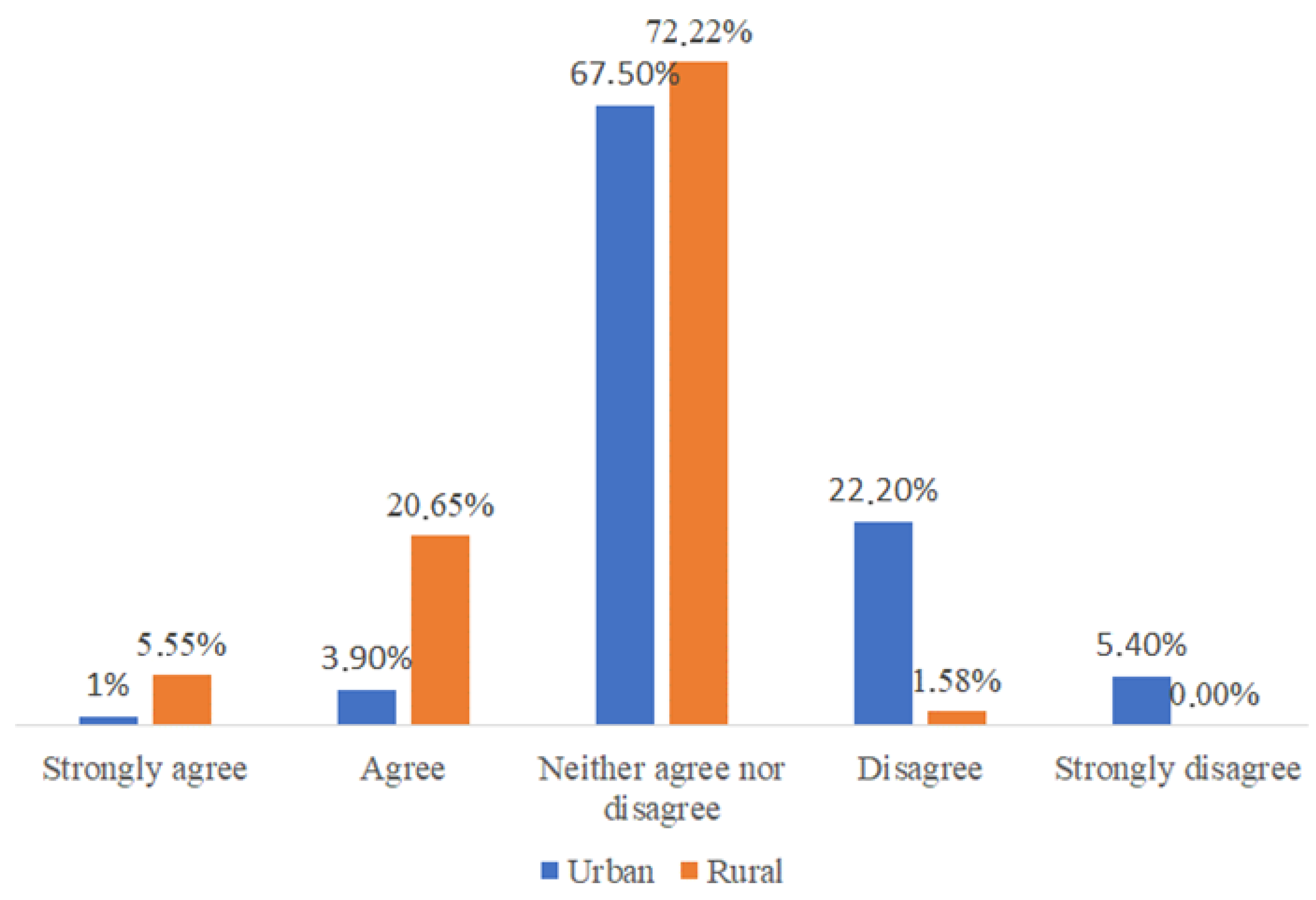

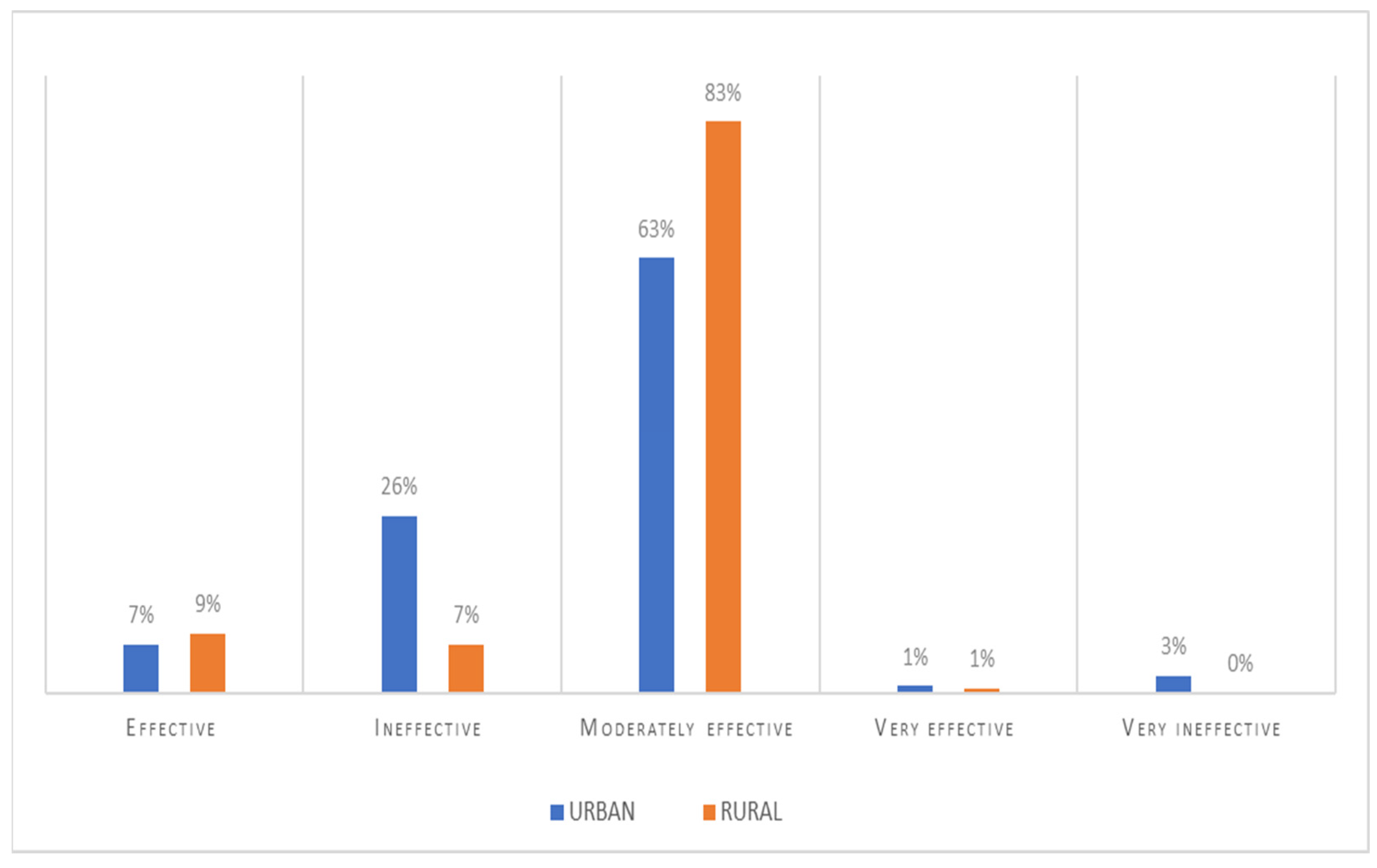

4.2. Water Management Perception

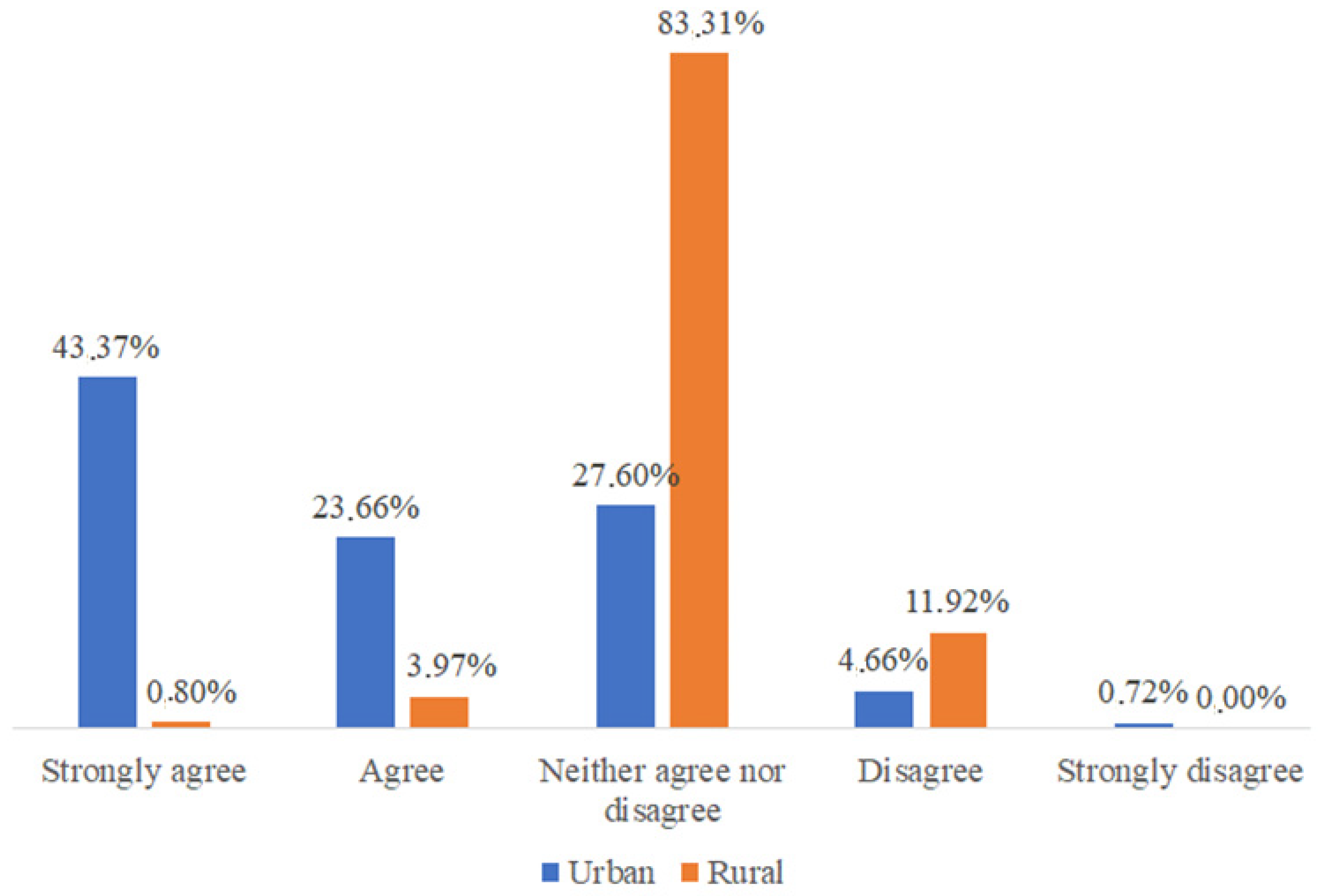

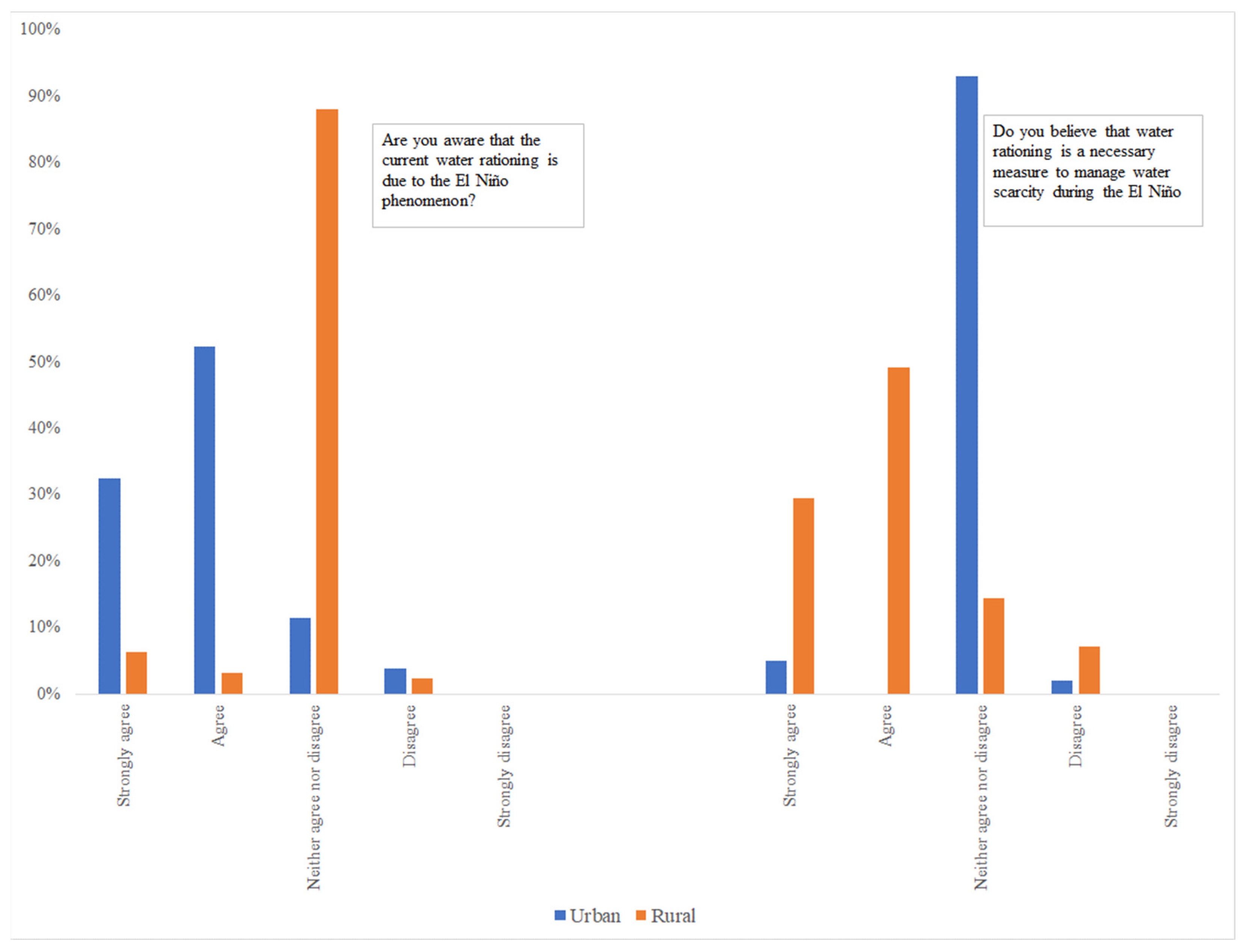

4.3. El Niño Southern Oscillation Phenomenon Perception

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, W.; McPhaden, M.J.; Grimm, A.M.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Taschetto, A.S.; Garreaud, R.D.; Dewitte, B.; Poveda, G.; Ham, Y.G.; Santoso, A.; et al. Climate Impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staupe-Delgado, R.; Kruke, B.I. El Niño-Induced Droughts in the Colombian Andes: Towards a Critique of Contingency Thinking. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, L.M.; Andreoli, R.V.; de Souza, I.P.; de Souza, R.A.F.; Kayano, M.T.; Ceron, W.L. South American Rainfall Variations Induced by Changes in Atmospheric Circulations during Reintensified and Persistent El Niño-Southern Oscillation Events. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 5499–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Builes-Jaramillo, A.; Valencia, J.; Salas, H.D. The Influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation Phase Transitions over the Northern South America Hydroclimate. Atmos. Res. 2023, 290, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, C.M.; Justino, F.; Gurjao, C.; Zita, L.; Alonso, C. Revisiting Climate-Related Agricultural Losses across South America and Their Future Perspectives. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yglesias-González, M.; Valdés-Velásquez, A.; Hartinger, S.M.; Takahashi, K.; Salvatierra, G.; Velarde, R.; Contreras, A.; María, H.S.; Romanello, M.; Paz-Soldán, V.; et al. Reflections on the Impact and Response to the Peruvian 2017 Coastal El Niño Event: Looking to the Past to Prepare for the Future. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayol, J.M.; Vásquez, L.M.; Valencia, J.L.; Linero-Cueto, J.R.; García-García, D.; Vigo, I.; Orfila, A. Extension and Application of an Observation-Based Local Climate Index Aimed to Anticipate the Impact of El Niño–Southern Oscillation Events on Colombia. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 5403–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Barco, J.; Hidalgo, C. Space-Time Analysis of the Relationship between Landslides Occurrence, Rainfall Variability and ENSO in the Tropical Andean Mountain Region in Colombia. Landslides 2024, 21, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Dueñas, S.; Bateman, A.; Santos Granados, G.R. Untangling the Implications of Climate-Forcing and Human-Induced Drivers in Streamflow Variability: The Magdalena River, Colombia. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Trejo, F.; Olivares, B.O.; Movil-Fuentes, Y.; Arevalo-Groening, J.; Gil, A. Assessing the Spatiotemporal Patterns and Impacts of Droughts in the Orinoco River Basin Using Earth Observations Data and Surface Observations. Hydrology 2023, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, J.C.; Guáqueta-Solórzano, V.E.; Castañeda, E.; Ortiz-Guerrero, C.E. Adaptive Responses and Resilience of Small Livestock Producers to Climate Variability in the Cruz Verde-Sumapaz Páramo, Colombia. Land 2024, 13, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, J.A.; Puerta-Cortés, D.X.; Andrade, H.J. Predictive Analysis of Adaptation to Drought of Farmers in the Central Zone of Colombia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombia Drought: Four-Minute Showers—A Parched Bogota Rations Water. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-68795071 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Atay, I.; Saladié, Ò. Water Scarcity and Climate Change in Mykonos (Greece): The Perceptions of the Hospitality Stakeholders. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 765–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, M.; Vignola, R.; Aliotta, Y. Smallholders’ Water Management Decisions in the Face of Water Scarcity from a Socio-Cognitive Perspective, Case Study of Viticulture in Mendoza. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyach, R.; Remr, J. Motivations of Households towards Conserving Water and Using Purified Water in Czechia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Osbahr, H.; Dorward, P. The Implications of Rural Perceptions of Water Scarcity on Differential Adaptation Behaviour in Rajasthan, India. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 2417–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkou, M.C.; McEvoy, J. Trust Matters: Why Augmenting Water Supplies via Desalination May Not Overcome Perceptual Water Scarcity. Desalination 2016, 397, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaawen, S. Understanding Climate Change and Drought Perceptions, Impact and Responses in the Rural Savannah, West Africa. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.H.; Buijs, A.E. Understanding Stakeholders’ Attitudes toward Water Management Interventions: Role of Place Meanings. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W01503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalla, O.Z.; Tumbo, M.; Joseph, J. Multi-Stakeholder Platform in Water Resources Management: A Critical Analysis of Stakeholders’ Participation for Sustainable Water Resources. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye-Ansah, A.S.; Schwartz, K.; Zwarteveen, M. Aligning Stakeholder Interests: How ‘Appropriate’ Technologies Have Become the Accepted Water Infrastructure Solutions for Low-Income Areas. Util. Policy 2020, 66, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, W.L.; Heyman, J.M. A Comprehensive Process for Stakeholder Identification and Engagement in Addressing Wicked Water Resources Problems. Land 2020, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H.; Wong, H.L.; Elfithri, R.; Teo, F.Y. A Review of Stakeholder Engagement in Integrated River Basin Management. Water 2022, 14, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W.M.; Brasier, K.J.; Burbach, M.E.; Whitmer, W.; Engle, E.W.; Burnham, M.; Quimby, B.; Kumar Chaudhary, A.; Whitley, H.; Delozier, J.; et al. A Conceptual Framework for Social, Behavioral, and Environmental Change through Stakeholder Engagement in Water Resource Management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparán, A.C. La Teoría de Los Campos En Pierre Bourdieu. Polis 1998, 1, 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason on the Theory of Action; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780804733632. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Perucich, F.; Arias-Loyola, M. Commodification in Urban Planning: Exploring the Habitus of Practitioners in a Neoliberal Context. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Delsaut, Y. Pour Une Sociologie de La Perception. Actes Rech. Sci. Soc. 1981, 40, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empresa de Servicios Públicos del Distrito de Santa Marta—ESSMAR E. S.P. PROTOCOLO DE ACTUACIÓN FENÓMENO DEL NIÑO Y/O SEQUÍA; Empresa de Servicios Públicos del Distrito de Santa Marta: Santa Marta, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Menghistu, H.T.; Mersha, T.T.; Abraha, A.Z. Farmers’ Perception of Drought and Its Socioeconomic Impact: The Case of Tigray and Afar Regions of Ethiopia. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuswanto, H.; Hibatullah, F.; Soedjono, E.S. Perception of Weather and Seasonal Drought Forecasts and Its Impact on Livelihood in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifundza, L.S.; van der Zaag, P.; Masih, I. Evaluation of the Responses of Institutions and Actors to the 2015/2016 El Niño Drought in the Komati Catchment in Southern Africa: Lessons to Support Future Drought Management. Water SA 2019, 45, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udmale, P.; Ichikawa, Y.; Manandhar, S.; Ishidaira, H.; Kiem, A.S. Farmers’ Perception of Drought Impacts, Local Adaptation and Administrative Mitigation Measures in Maharashtra State, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 10, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauberghe, V.; Vazquez-Casaubon, E.; Van de Sompel, D. Perceptions of Water as Commodity or Uniqueness? The Role of Water Value, Scarcity Concern and Moral Obligation on Conservation Behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husu, H.M. Rethinking Incumbency: Utilising Bourdieu’s Field, Capital, and Habitus to Explain Energy Transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 93, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, B.; Donovan, B. Hydrologic Habitus: Wells, Watering Practices, and Water Supply Infrastructure. Nat. Cult. 2020, 15, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, R.; Upham, P.; Kurronen, K. Social Capital, Resource Constraints and Low Growth Communities: Lifestyle Entrepreneurs in Nicaragua. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Feyzabad, F.; Yazdanpanah, M.; Burton, R.J.F.; Forouzani, M.; Mohammadzadeh, S. The Use of a Bourdieusian “Capitals” Model for Understanding Farmer’s Irrigation Behavior in Iran. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591, 125442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial. Política Nacional Para La Gestión Integral del Recurso Hídrico; Ministerio de Ambiente Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2010; ISBN 9789588491356.

- De Luque-Villa, M.A.; González-Méndez, M. Water Management in Colombia from the Socio-Ecological Systems Framework. In WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2022; Volume 259, pp. 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Medina, M.A.; Nieto-Rodríguez, M.A. Governability or Governance in Water Resource Management. The Colombian Case. Rev. Repub. 2020, 2020, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorocho-Daza, H.; Cabrales, S.; Santos, R.; Saldarriaga, J. A New Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Methodology for the Selection of New Water Supply Infrastructure. Water 2019, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Leira, F.D.J.; Navarro Hernández, P.L.; Sossa Álvarez, R.D. Efectos Del Desabastecimiento de Agua Potable En Empresas Turísticas. El Caso de Santa Marta (Colombia). Rev. CEA 2023, 9, e2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey Inc. SurveyMonkey Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://es.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Jebb, A.T.; Ng, V.; Tay, L. A Review of Key Likert Scale Development Advances: 1995–2019. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 637547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpur, M.A.H.; Khahro, S.H.; Khan, M.S.; Shaikh, F.A.; Javed, Y. Aftermaths of COVID-19 Lockdown on Socioeconomic and Psychological Nexus of Urban Population: A Case in Hyderabad, Pakistan. Societies 2024, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbi, A.W.; Watanabe, T. Differences in Risk Perception of Water Quality and Its Influencing Factors between Lay People and Factory Workers for Water Management in River Sosiani, Eldoret Municipality Kenya. Water 2020, 12, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumah, M.; Yeboah, A.S.; Bonyah, S.K. What Matters Most? Stakeholders’ Perceptions of River Water Quality. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, G.; Hooks, T.; McDermott, F. Water Quality Perceptions and Private Well Management: The Role of Perceived Risks, Worry and Control. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 267, 110654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricotta, C.; Pavoine, S. A New Parametric Measure of Functional Dissimilarity: Bridging the Gap between the Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity and the Euclidean Distance. Ecol. Model. 2022, 466, 109880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lira Azevêdo, E.; Alves, R.R.N.; Dias, T.L.P.; Álvaro, É.L.F.; De Lucena Barbosa, J.E.; Molozzi, J. Perception of the Local Community: What Is Their Relationship with Environmental Quality Indicators of Reservoirs? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusack, E.M.; Dortch, J.; Hayward, K.; Renton, M.; Boer, M.; Grierson, P. The Role of Habitus in the Maintenance of Traditional Noongar Plant Knowledge in Southwest Western Australia. Hum. Ecol. 2011, 39, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.T.; Van Lissa, C.J.; Verhagen, M.; Hoemann, K.; Erbaş, Y.; Maciejewski, D.F. A Theory-Informed Emotion Regulation Variability Index: Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity. Emotion 2024, 24, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Ivybridge, UK, 2008; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Rios, D.; Montes-Correa, A.C.; Urbina-Cardona, J.N.; De Luque-Villa, M.; E Cattan, P.; Granda, H.D. Local Community Knowledge and Perceptions in the Colombian Caribbean towards Amphibians in Urban and Rural Settings: Tools for Biological Conservation. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2021, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rubiano, M.; Gómez-Sánchez, J.; Robledo-Buitrago, D.; De Luque-Villa, M.; Urbina-Cardona, J.N.; Granda-Rodriguez, H. Perception and Attitudes of Local Communities towards Vertebrate Fauna in the Andes of Colombia: Effects of Gender and the Urban/Rural Setting. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2023, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N.; Sommerfield, P.J.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities—Statistical Analysis; Primer-E: Plymouth, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, A.; Saeed, S.; Ahmad, S.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, A. Empowering Community Participation for Sustainable Rural Water Supply: Navigating Water Scarcity in Karak District Pakistan. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 26, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoin, L.; Arenas, D. From Raindrops to a Common Stream: Using the Social-Ecological Systems Framework for Research on Sustainable Water Management. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, V.; Gholamrezai, S.; Ataei, P. Rural People’s Intention to Adopt Sustainable Water Management by Rainwater Harvesting Practices: Application of TPB and HBM Models. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2020, 20, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, H.; Kuper, M.; Passos Rodrigues Martins, E.S.; Morardet, S.; Burte, J. Sustaining Community-Managed Rural Water Supply Systems in Severe Water-Scarce Areas in Brazil and Tunisia. Cah. Agric. 2022, 31, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talanow, K.; Topp, E.N.; Loos, J.; Martín-López, B. Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies in South Africa’s Western Cape. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Luque-Villa, M.A.; Granda-Rodríguez, H.D.; Garza-Tatis, C.I.; González-Méndez, M. Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to Public Perceptions of Water Scarcity during El Niño: A Case Study of Santa Marta, Colombia. Societies 2024, 14, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100201

De Luque-Villa MA, Granda-Rodríguez HD, Garza-Tatis CI, González-Méndez M. Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to Public Perceptions of Water Scarcity during El Niño: A Case Study of Santa Marta, Colombia. Societies. 2024; 14(10):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100201

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Luque-Villa, Miguel A., Hernán Darío Granda-Rodríguez, Cristina Isabel Garza-Tatis, and Mauricio González-Méndez. 2024. "Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to Public Perceptions of Water Scarcity during El Niño: A Case Study of Santa Marta, Colombia" Societies 14, no. 10: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100201

APA StyleDe Luque-Villa, M. A., Granda-Rodríguez, H. D., Garza-Tatis, C. I., & González-Méndez, M. (2024). Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to Public Perceptions of Water Scarcity during El Niño: A Case Study of Santa Marta, Colombia. Societies, 14(10), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100201