Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Women Defenders in the Face of the Socio-Environmental Crisis and the Care Crisis

1.2. Socio-Environmental Conflict in Latin America, Mexico, and Jalisco

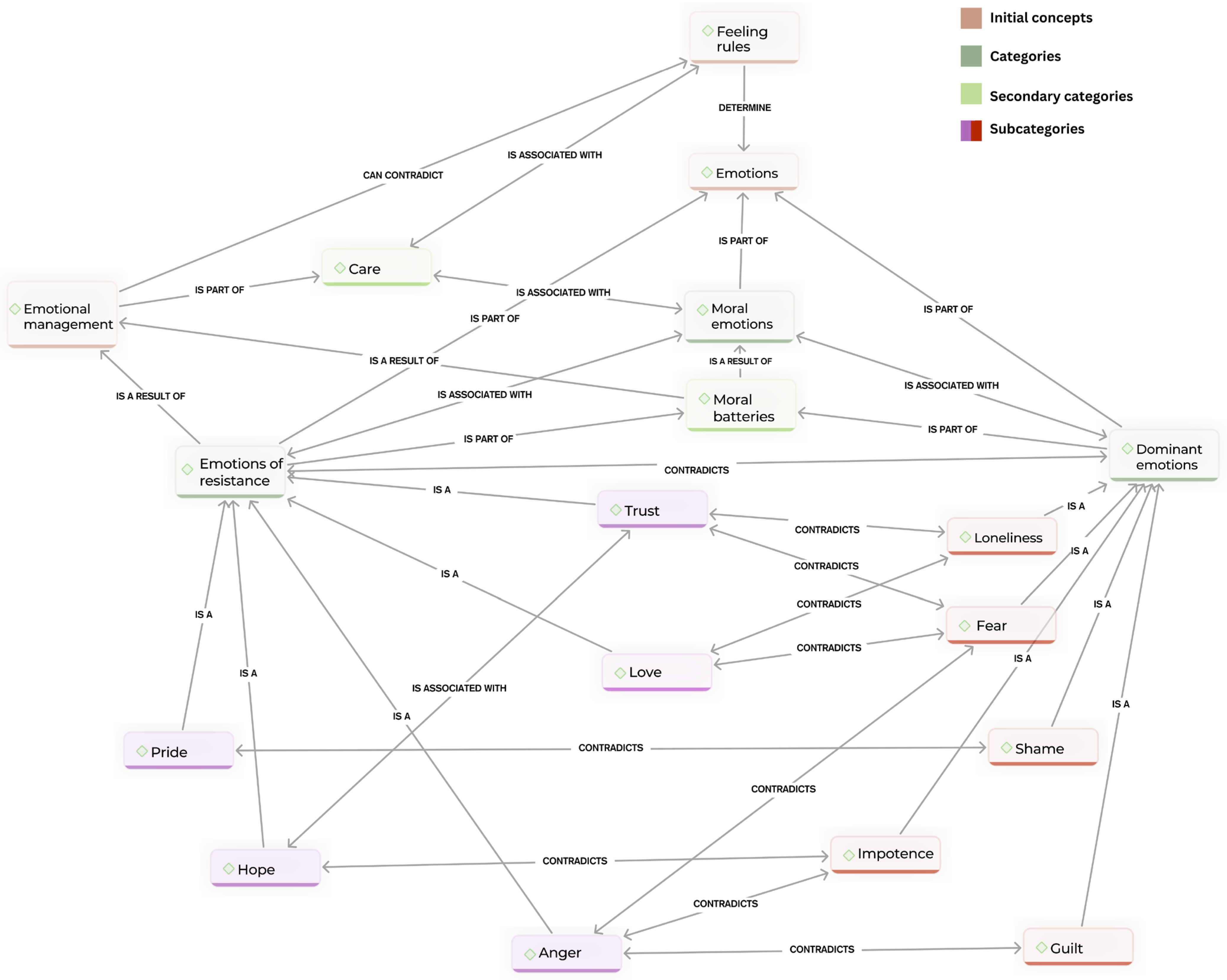

1.3. Theoretical Analytical Perspective: Emotional Management and Emotions of Resistance

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Study Contexts and Participants

- Antiquity: This criterion made it possible to observe the relational dimension throughout time, their internal culture, memory, and the emotions and place attachment related to the group domain. This way, groups in different stages of evolution were integrated into the studied sample.

- Geographical aspects: The geographic location of the groups or individuals defending their territories determines the type of conflict, resistance practices, and place attachments. Including groups and individuals with attachments to different territories implied observing different ways of emotional bonding with places, which also determines their resistance and political strategies.

- Sociocultural diversity: This criterion considers the diversity of sociocultural profiles regarding class, age, gender, education, history, and community practices. This helped identify differences and similarities between the types of attachment to the place, their defense of place practices, and their motivations and meanings linked to specific cultural configurations.

2.2. Coding and Analytical Approach

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fear: A Multilayer Emotion

3.2. Guilt and Shame to Preserve Care Systems

3.3. Loneliness, Friendship, and Motherhood

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poma, A.; Gravante, T. Las emociones como arena de la lucha política. Incorporando la dimensión emocional al estudio de la protesta y los movimientos sociales. Ciudad. Act. 2015, 3, 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, M.F. Deterioro y resistencias. Conflictos socioambientales en México. In Conflictos Socioambientales y Alternativas de la Sociedad Civil, 1st ed.; Tetreault, D., Ochoa, H., Hernández, E., Eds.; ITESO: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2012; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss, D.M. Las Formas de Apropiación del Espacio en la Defensa del Lugar: El caso de la Cooperativa Mujeres Ecologistas de la Huizachera. Master’s Thesis, ITESO, Guadalajara, México, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss, D.M. Del Corazón a la Organización: El Apego al Lugar en Experiencias de Defensa del Territorio en Jalisco. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss, D.M. Reclaiming the Right to Become Other Women in Other-Places: The Politics of Place of the Ecologist Women of La Huizachera Cooperative, Mexico. In Bodies in Resistance Gender Politics in The Age of Neoliberalism, 1st ed.; Harcourt, W., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, A. The Managed Heart, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt, W.; Escobar, A. Las Mujeres y las Políticas del Lugar, 1st ed.; UNAM: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, A.R. Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. Am. J. Sociol. 1979, 85, 551–575. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778583 (accessed on 1 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lang, M. Simulación e irresponsabilidad: El ‘desarrollo’ frente a la crisis civilizatoria. Miradas críticas desde los feminismos y el pensamiento decolonial sobre los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sustentable y la erradicación de la pobreza. Gestión Ambiente 2021, 24 (Suppl. S1), 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, E. Toolkit for the European Union on Women Human Rights Defenders; Front Line Defenders: Dublin, Ireland, 2020; Available online: http://www.frontlinedefenders.org (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Hadad, G. Resistencias y alternativas del pueblo Mapuche frente al fracking en Vaca Muerta (Neuquén, Argentina). In Defensa del Territorio, la Cultura y la Vida ante el Avance Extractivista, 1st ed.; Pereira, H., da Silva Ramos Filho, E., Herrera, A., Eds.; CEPAL: Buenos Aires, Asunción, 2022; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss Nuñez, D.; García Chapinal, I. Environmental Knowledges in Resistance Mobilization, (Re)Production, and the Politics of Place. The Case of the Cooperativa Mujeres Ecologistas de la Huizachera, Jalisco (Mexico). In Feminism in Movement, 1st ed.; Gender Studies; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2023; pp. 261–673. Available online: https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839461020-018#read-container (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Tran, D. A comparative study of women environmental defenders’ antiviolent success strategies. Geoforum 2021, 126, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, E.M. Mobilizing motherhood: The gendered burden of environmental protection. Sociol Compass 2021, 15, e12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fair Share for Health and Care: Gender and the Undervaluation of Health and Care Work, 1st ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Camey, I.; Sabater, L.; Owren, C.; Boyer, A.E. Vínculos Entre la Violencia de Género y el Medio Ambiente la Violencia de la Desigualdad, 1st ed.; Wen, J., Ed.; UICN: Gland, Suiza, 2020; Available online: https://www.iucn.org/es (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- UN Women. News and Stories. Explainer: How Gender Inequality and Climate, Change Are Interconnected. 2022. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2022/02/explainer-how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Schilliger, S.; Schwiter, K.; Steiner, J. Care crises and care fixes under COVID-19: The example of transnational live-in care work. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2023, 24, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcena, A.; Castillo, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Exacerbating the Care Crisis in Latin America and the Caribbean [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/37b9630e-15a3-49d9-bdfc-eb024f71510b/content (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Cascella Carbó, G.F.; García-Orellán, R. Burden and Gender inequalities around Informal Care. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2020, 38, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodly, D.; Brown, R.H.; Marin, M.; Threadcraft, S.; Harris, C.P.; Syedullah, J.; Ticktin, M. The Politics of Care. Contemporary Political Theory [Internet]. Politics Care 2021, 20, 890–925. Available online: https://www.palgrave.com/journals (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Miranda, F.; Castañeda, I.; Román, P.; Velázquez, M.; Acción Climática con Igualdad de Género [Internet]. Santiago de Chile. 2022. Available online: https://www.issuu.com/publicacionescepal/stacks (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Zibechi, R. El Pensamiento Crítico ante los Desafíos de Abajo. Bajo Volcán 2020, 1, 19–38. Available online: http://www.apps.buap.mx/ojs3/index.php/bevol/article/view/1909/1464 (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. Women Environmental Human Rights Defenders: Facing Gender-Based Violence in Defense of Land, Natural Resources and Human Rights [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/union/sites/union/files/doc/iucn-srjs-briefs-wehrd-gbv-en_0.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Ferrando, T.; Vispo, I.A.; Anderson, M.; Dowllar, S.; Friedmann, H.; Gonzalez, A.; Mckeon, N. Land, territory and commons: Voices and visions from the struggles. Globalizations 2020, 17, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Zamora, V. The coloniality of neoliberal biopolitics: Mainstreaming gender in community forestry in Oaxaca, Mexico. Geoforum 2021, 126, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Hanaček, K. A global analysis of violence against women defenders in environmental conflicts. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bene, D.; Martínez Alier, J. Global Atlas of Environmental Justice [Internet]. Available online: https://ejatlas.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- México Ambiental. México Ambiental. Investigadores de la UNAM, Revelan Más de 500 Conflictos Ambientales en México y CONSTRUYE Mapa que los Georeferencia y Categoriza. 2018. Available online: https://www.mexicoambiental.com/investigadores-de-la-unam-revelan-mas-de-500-conflictos-ambientales-en-mexico-y-construye-mapa-que-los-georeferencia-y-categoriza/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Camacho, F. Documentan 400 Conflictos Ambientales en México en Cuatro años. La Jornada. 2024. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2024/02/15/politica/013n3pol (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Toledo, V.M. Ecocidio en México. La Batalla Final es por la Vida, 1st ed.; Grijalbo: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, R. Resistencias Frente a la Acumulación por Despojo en México. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; Malkin, E. Un Chernóbil en Cámara Lenta. New York Times [Internet]. 1 January 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/es/2020/01/01/espanol/america-latina/mexico-medioambiente-tmec.html (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Greenpeace. Estudio de la Contaminación en la Cuenca del Río Santiago y la Salud Pública en la Región [Internet]. 2012. Available online: http://www.greenpeace.org/mexico/global/mexico/report/2012/9/informe_toxicos_rio_santiago.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Tribunal Interamericano del Agua. Caso: Deterioro y Contaminación del río Santiago. Municipios de El Salto y Juanacatlán, estado de Jalisco, República Mexicana [Internet]. Tribunal Interamericano del Agua. 2007. Available online: https://tragua.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/caso_rio_santiago_mexico.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Comisión Estatal del Agua de Jalisco. Propuesta Metodológica para la Implantación de una Batería de Indicadores de Salud que Favorezcan el establecimiento de Programas de Diagnóstico, Intervención y Vigilancia Epidemiológica en las Poblaciones Ubicadas en la Zona de Influencia del Proyecto de la Presa Arcediano en el Estado de Jaliscoo. San Luis Potosí. UASLP-CEA, Mexico. 2010. Available online: https://transparencia.info.jalisco.gob.mx/sites/default/files/u531/INFORME%20FINAL%20ARCEDIANO_CEA_UEAS_JALISCO_2011_1%20-%20copia_opt.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Meléndez, V. Dañan Plaguicidas a Niños en Autlán. El Diario NTR [Internet]. 19 August 2019. Available online: https://www.ntrguadalajara.com/post.php?id_nota=132626 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Whittier, N. Emotional Strategies: The Collective Reconstruction and Display of Oppositional Emotions in the Movement against Child Sexual Abuse. In Passionate Politics Emotions and Social Movements, 1st ed.; Goodwin, J., Jasper, J., Polletta, F., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gravante, T.; Poma, A. Manejo emocional y acción colectiva: Las emociones en la arena de la lucha política. Estud. Sociológicos 2018, 36, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravante, T. Forced Disappearance as a Collective Cultural Trauma in the Ayotzinapa Movement. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2020, 47, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, J. The Emotions of Protest, 1st ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saukko, P. Metodologías para los estudios culturales. Paradigmas y perspectivas en disputa. In Manual de Investigación Cualitativa, 1st ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Brazil, 2012; pp. 316–340. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A.I. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, J. Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flam, H. Emotion’s map: A research agenda. In Emotions and Social Movements, 1st ed.; Flam, H., King, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez González, A.; González Villamizar, J. Intersectional Praxis and Socio-Political Transformation at the Colombian Truth Commission in the Caribbean Region. In Feminism in Movement, 1st ed.; De Souza Lima, L., Otero Quezada, E., Roth, J., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Beliefild, Germany, 2023; pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.J. Commoning for inclusion? commons, exclusion, property and socio-natural becomings. Int. J. Commons 2019, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloss, D.M. Defensa del territorio y disrupción del apego al lugar: El caso el Salto y Juanacatlán, Jalisco. In Emociones y Medio Ambiente Un Enfoque Interdisciplinario, 1st ed.; Poma, A., Gravante, T., Eds.; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Batthyány, K. Políticas del Cuidado [Internet]. Buenos Aires y Ciudad de México. 2021. Available online: https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20210406022442/Politicas-cuidado.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Hernando, A. La Fantasía de la Individualidad. Sobre la Construcción Sociohistórica del Sujeto Moderno, 1st ed.; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://traficantes.net/libros/la-fantas%C3%ADa-de-la-individualidad (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Paredes Carvajal, J. Territory Body-Body Territory. In Feminisms in Movement, 1st ed.; De Souza Lima, L., Otero Quezada, E., Roth, J., Eds.; Gender Studies; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2023; pp. 147–158. Available online: https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839461020-009#read-container (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Sara, A.; Cecilia, O. La Política Cultural de las Emociones, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Programa Universitario de Estudios de Género: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; 366p. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gloss Nuñez, D.M.; Nuñez Fadda, S.M. Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco. Societies 2024, 14, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100194

Gloss Nuñez DM, Nuñez Fadda SM. Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco. Societies. 2024; 14(10):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100194

Chicago/Turabian StyleGloss Nuñez, Daniela Mabel, and Silvana Mabel Nuñez Fadda. 2024. "Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco" Societies 14, no. 10: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100194

APA StyleGloss Nuñez, D. M., & Nuñez Fadda, S. M. (2024). Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco. Societies, 14(10), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14100194