Inclusionary Leadership-Perspectives, Experiences and Perceptions of Principals Leading Autism Classes in Irish Primary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership for Inclusion in an Irish Context

1.2. Language of Inclusive Leadership

1.3. Roles That Principals Play When Leading for Inclusion

1.4. Defining a Model of Inclusive School Leadership

1.5. Transformational Leadership

1.6. Distributed Leadership

1.7. Instructional Leadership

1.8. Combining Models of Leadership

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. Data Collection Development

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

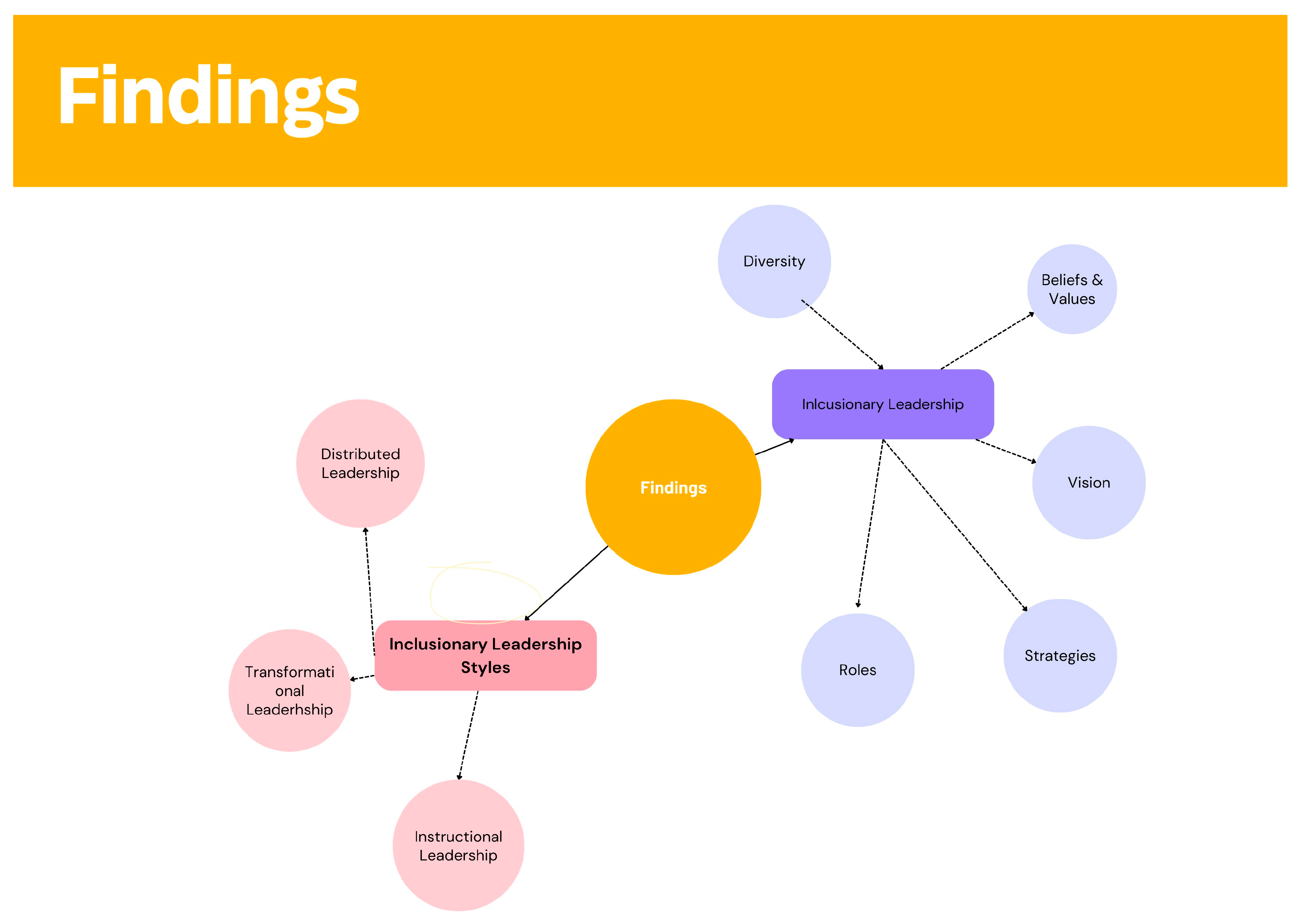

3. Results

3.1. Principal Beliefs and Values

3.2. A Broader Vision of Inclusion

“I think over time, my attitude to that word has changed entirely. Primarily, probably because of the autism classes here. …. So I would say that we’re including them in other ways other than the academic way. …and I can definitely see inclusion.” (CK).

3.3. Autism Classes as a Model of Distributed Leadership

3.4. Strategies to Promote Inclusion

3.5. Inclusion as a Means of Diversity

3.6. Principals Envisioning of Inclusion

“I think that’s going to be a huge equality issue down the line, if there’s going to be children who maybe could have done better in life in terms of maybe having held down a job or held down relationships or whatever... Because the support and therapy that they needed, wasn’t there, there was only so much the school can do” (CK).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Inclusionary Principal

4.2. Limitations to the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions

Is there anything you would like to add or something you wish I had asked you? |

| 1 | Special Educational Needs Co-Ordinator. |

| 2 | Name changed to protect identity. |

References

- Kenny, N.; McCoy, S.; Mihut, G. Special education reforms in Ireland: Changing systems, changing schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, J.; Lenkeit, J.; Hartmann, A.; Ehlert, A.; Knigge, M.; Spörer, N. The effect of school leadership on implementing inclusive education: How transformational and instructional leadership practices affect individualised education planning. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, M.; Green, D.A. Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2012, 31, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, J.L.; White, G.; Roberts, L. Principals’ Attitudes Regarding Inclusion of Children with Autism in Pennsylvania Public Schools. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüddeckens, J.; Anderson, L.; Östlund, D. Principals’ perspectives of inclusive education involving students with autism spectrum conditions–a Swedish case study. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of research on school leadership in the Republic of Ireland. J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 57, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a crossroads: Dismantling Ireland’s system of special education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A.; King, F.; Travers, J. Supporting the enactment of inclusive pedagogy in a primary school. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 1540–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Radford, J. Leadership for inclusive special education: A qualitative exploration of SENCOs’ and principals’ Experiences in secondary schools in Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 26, 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. A winning formula? Funding inclusive education in Ireland. In Resourcing Inclusive Education; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, C. Principals play many parts: A review of the research on school principals as special education leaders 2001–2011. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Skills. Looking at Our School 2016, A Quality Framework for Primary Schools; The Inspectorate Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2016.

- Óskarsdóttir, E.; Donnelly, V.; Turner-Cmuchal, M.; Florian, L. Inclusive school leaders–their role in raising the achievement of all learners. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J.W. Competencies and Their Assessment. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2014, 50, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, W. Organising inclusive schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 1340–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Radford, J. The SENCO role in post-primary schools in Ireland: Victims or agents of change? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Science (Ed.) Inclusion of Students with Special Educational Needs: Primary Guidelines; Stationary Office: Dubline, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Long, S. Developing Knowledge and Understanding of Autism Spectrum Difference. In Autism from the Inside Out; Ring, E.D., Eugene, P.W., Eds.; Peter Lang: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J. Leadership in Inclusive Special Education: A Qualitative Exploration of the Senco Role in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, S. The Impact of ‘Achievement for All’ on School Leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickaitė, J. The expression of a principal’s transformational leadership during the organizational change process: A case study of Lithuanian general education schools. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2013, 51, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Teaching Council. Policy on the Continuum of Teacher Education; The Teaching Council, Maynooth. Co.: Kildare, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, S.; Hardy, I. Probing and problematizing teacher professional development for inclusion. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 83, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D.; Boyatzis, R.E.; McKee, A. The New Leaders: Transforming the Art of Leadership into the Science of Results; Sphere: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Situmorang, M.; Situmeang, C.M. Student Character Education Towards Excellence: Optimization of Transformational Leadership of Lecturers. EDUKASIA J. Pendidik. Pembelajaran 2022, 3, 865–872. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, N.; Flaherty, A.; Mannix McNamara, P. Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research. Societies 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, N.; Flaherty, A.; Mannix McNamara, P. Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: According to the evidence. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P. Distributed Leadership. Educ. Forum 2005, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Harris, A. Principals leading successful organisational change: Building social capital through disciplined professional collaboration. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2014, 27, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Torres, D. Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction in U.S. schools. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Ng, A.Y.M. Distributed leadership and the Malaysia Education Blueprint: From prescription to partial school-based enactment in a highly centralised context. J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed Leadership Matters: Perspectives, Practicalities, and Potential; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Munna, A.S. Instructional leadership and role of module leaders. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2023, 32, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyati, N.; Riyanto, Y.; Sujarwanto, S.; Suyatno, S.; Islamiah, N. Actualization of Principal Instructional Leadership in the Implementation of Differentiated Learning to Realize Students’ Well-Being. J. Kependidikan J. Has. Penelit. Kaji. Kepustakaan Bid. Pendidik. Pengajaran Pembelajaran 2023, 9, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, M.; Stoll, L.; George, B.; Steijn, B.; Bekkers, V.; Gouëdard, P. The school as a learning organisation: The concept and its measurement. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 55, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPPN. Primary School Leadership: The Case for Urgent Action—A Roadmap to Sustainability; IPPN: Cork, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mbua, E.M. Principal Leadership: Raising the Achievement of All Learners in Inclusive Education. Am. J. Educ. Pract. 2023, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H.; Jago, A.G. The role of the situation in leadership. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis—A Practical Guide; SAGE: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdinelli, S.; Scagnoli, N.I. Data display in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Implications for the role of the principal. J. Manag. Dev. 2012, 31, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed properties: A new architecture for leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. 2000, 28, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. Educational leadership for what? An educational examination. In The Wiley International Handbook of Educational Leadership; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.; Cahill, K. An investigation into the experiences and identity of special class teachers in Irish primary schools. Ir. Teach. J. 2020, 8, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kuknor, S.C.; Bhattacharya, S. Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 46, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID 19—School leadership in disruptive times. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Byrne, D.; Bryan, A.; Kitching, K.; Ní Chróinín, D.; O’Toole, C.; Addley, J. COVID-19 and education: Positioning the pandemic; facing the future. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colum, M.; Collins, A. Conversations on COVID-19: A viewpoint on care, connections and culture during the pandemic from a teacher educator and an Irish Traveller. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, A.; Tsirantonaki, S.S. The Importance of School Principals’ Values towards the Inclusive Education of Disabled Students: Associations between Their Values and Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitudes and Practices. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P. Distributed Leadership; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue, C. From heroes and heroines to hermaphrodites: Emasculation or emancipation of school leaders and leadership? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2009, 29, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S. An Irish solution…? Questioning the expansion of special classes in an era of inclusive education. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2017, 48, 441–461. [Google Scholar]

- Moloney, M.; McCarthy, E. Intentional Leadership for Effective Inclusion in Early Childhood Education and Care: Exploring Core Themes and Strategies; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin, M.; Flynn, P. School Leadership for Special Educational Needs. In Leading and Managing Schools; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- King, F. Evolving perspective (s) of teacher leadership: An exploration of teacher leadership for inclusion at preservice level in the Republic of Ireland. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2017, 45, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, A.; Brennan, A. Leading the Special Education Teacher Allocation Model Examining the Perspectives and Experiences of School Leaders in Supporting Special and Inclusive Education in Irish Primary Schools. REACH J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2021, 34. Available online: https://reachjournal.ie/index.php/reach/article/view/320 (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Harris, A. Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: Heresy, fantasy or possibility? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2003, 23, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, C.; Kinsella, W.; Prendeville, P. The professional development needs of primary teachers in special classes for children with autism in the republic of Ireland. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, J.A.; O’Donovan, M. Learning and teaching: The extent to which school principals in Irish voluntary secondary schools enable collaborative practice. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2022, 41, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusive Programme Delivery. Cobb (2015) [12] | Staff Collaboration. Cobb (2015) [12] | Parental Engagement. Cobb (2015) [12] | SENCO1 Role in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland. Fitzgerald (2017) [20] | Organising Inclusive Schools. Kinsella (2020) [16] | SENCO & Principal’s Experiences. Fitzgerald and Radford (2020) [10] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visionary | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Partner/Collaborator/mentor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Coach | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Conflict resolver/Arbiter | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Advocate | ✓ | |||||

| Interpreter | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Organiser/coordinator | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Consulter | ✓ | |||||

| Communicator | ✓ | |||||

| Rescuer | ✓ | |||||

| Expert | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dennehy, L.; Cahill, K.; Moynihan, J.A. Inclusionary Leadership-Perspectives, Experiences and Perceptions of Principals Leading Autism Classes in Irish Primary Schools. Societies 2024, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010004

Dennehy L, Cahill K, Moynihan JA. Inclusionary Leadership-Perspectives, Experiences and Perceptions of Principals Leading Autism Classes in Irish Primary Schools. Societies. 2024; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDennehy, Linda, Kevin Cahill, and Joseph A. Moynihan. 2024. "Inclusionary Leadership-Perspectives, Experiences and Perceptions of Principals Leading Autism Classes in Irish Primary Schools" Societies 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010004

APA StyleDennehy, L., Cahill, K., & Moynihan, J. A. (2024). Inclusionary Leadership-Perspectives, Experiences and Perceptions of Principals Leading Autism Classes in Irish Primary Schools. Societies, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010004