The Impact of Transformational School Leadership on School Staff and School Culture in Primary Schools—A Systematic Review of International Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Transformational Leadership Conceptualization

1.2. Transformational School Leadership

1.3. School Culture

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Purpose and Structure of Review

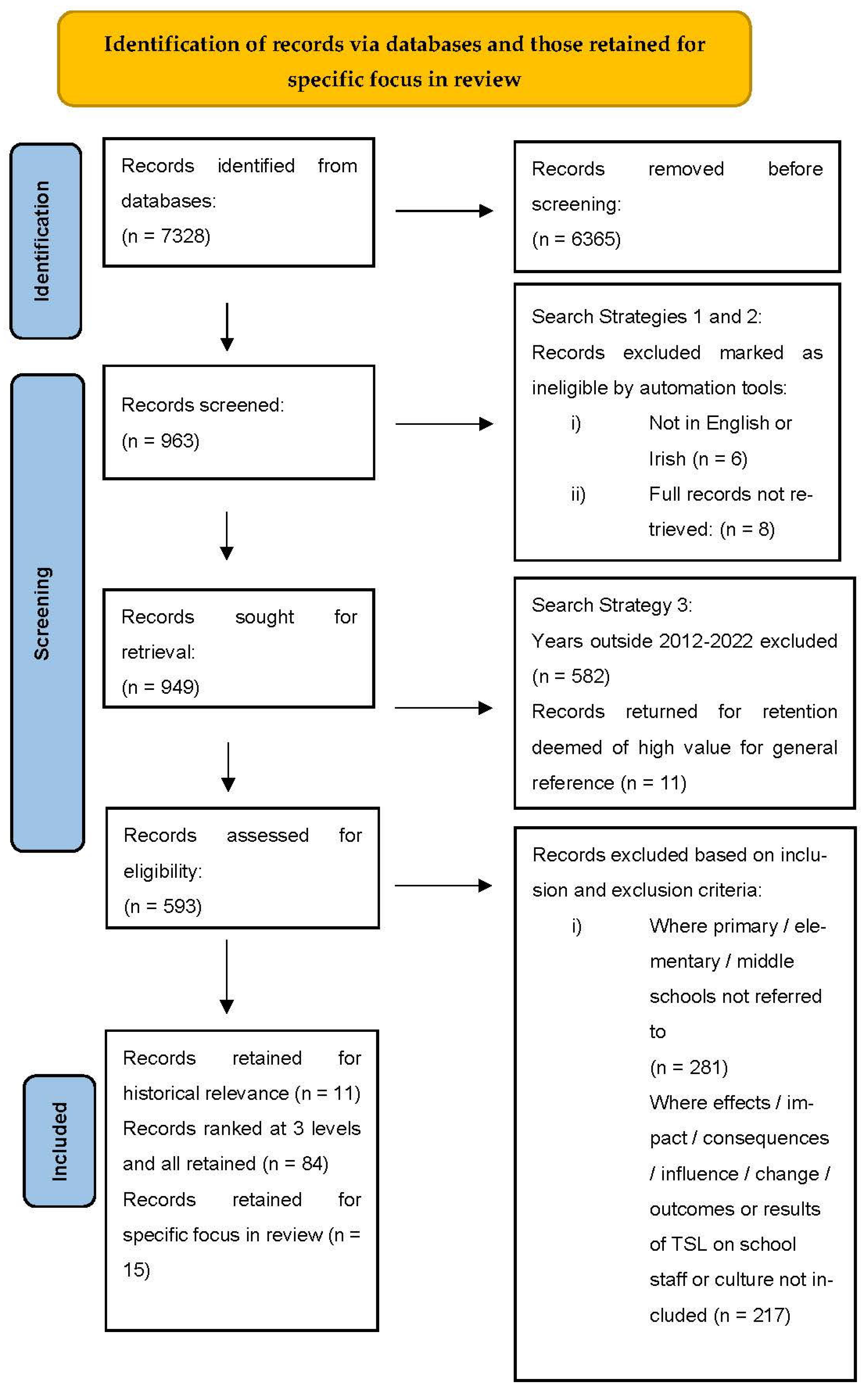

2.2. Search Strategies, Inclusion, and Exclusion Selection Criteria

2.3. Screening, Grading of Papers, and Resulting Documents for Synthesis

2.4. Records for Specific Focus and Appraisal

2.5. Analysis of Selected Studies

2.6. Characteristics of Selected Studies

3. Results

3.1. Literature Synthesis

- Idealised influence, providing an appropriate model, and modelling the way.

- Inspirational motivation, setting direction, inspiring, identifying and articulating a shared vision, and fostering acceptance of group goals.

- Individualised consideration, developing people, enabling others to act, and providing individualised support to school staff and culture.

- Intellectual stimulation, holding high-performance expectations, challenging the process, and encouraging the heart in school staff and school culture.

- Redesigning the organisation of school staff and culture.

- Improving the instructional programme of school staff and culture.

3.2. Results Presented in Two Separate Persepctives: Impacts on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.1. Impacts of the First Element of the Framework, ‘Idealized Influence, Providing an Appropriate Model, and Modelling the Way’, on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.2. Impact of the Second Element of the Framework, ‘Inspirational Motivation, Setting Direction, Inspiring, Identifying and Articulating a Shared Vision, and Fostering Acceptance of Group Goals’, on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.3. Impact of the Third Element of the Framework, ‘Individualized Consideration, Developing People, Enabling Others to Act, and Providing Individualized Support’, on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.4. Impact of the Fourth Element of the Framework, ‘Intellectual Stimulation, Holding High-Performance Expectations, Challenging the Process, and Encouraging the Heart’, on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.5. Impact of the Fifth Element of the Framework, ‘Redesigning the Organization’, on School Staff and School Culture

3.2.6. Impact of the Sixth Element of the Framework, ‘Improving the Instructional Programme’, on School Staff and School Culture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burton, L.; Peachey, J. Transactional or transformational? Leadership preferences of division III athletic administrators. J. Intercoll. Sport 2009, 2, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, M.; Brown-Welty, S. Case study of leadership practices and school community interrelationships in high-performing, high-poverty, rural California high schools. J. Res. Rural. Educ. 2009, 24, 1. Available online: https://jrre.psu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-08/24-1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Pepper, K. Effective principals skillfully balance leadership styles to facilitate student success: A focus for the reauthorization of ESEA. Plan. Chang. 2010, 41, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg, P. Will the pandemic change schools? J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treneman-Evans, G.; Ali, B.; Denison-Day, J.; Clegg, T.; Yardley, L.; Denford, S.; Essery, R. The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, N.; Shayya, R. The impacts of World Bank education programs in alleviating Middle East economies within Syrian refugee crisis. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2020, 19, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, C. Dealing with stress using social theatre techniques with young Syrian students adapting to a new educational system in Turkey: A case study. MHPSS Interv. 2018, 16, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.S. Are High-Poverty School Districts Disproportionately Impacted by State Funding Cuts? School Finance Equity Following the Great Recession. J. Educ. Financ. 2017, 43, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Molchaniuk, O.; Babakina, O.; Dmytrenko, K.; Kharkivska, A.; Kapustina, O. Partial programs in access to the social values: Technology that changes preschool education. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1691, 12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID 19—School leadership in disruptive times. School Leadership Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education GPS. 2023. Available online: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=42356&filter=all (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Lin, F.; Long, C.X. The impact of globalization on youth education: Empirical evidence from China’s WTO accession. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 178, 820–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giouroglou, C. Primary education stakeholders’ views on the European Union during the Greek economic crisis. Innov. J. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, L.; Ravenscroft, J.; Rizzini, I.; Tisdall, K.; Biersteker, L.; Shabalala, F.; S’lungile, K.T.; Dlamini, C.N.; Bush, M.; Gwele, M.; et al. The Impact of the Covid-19 Global Health Pandemic in Early Childhood Education Within Four Countries. J. Soc. Incl. 2022, 10, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, F. Walking on eggshells: Brexit, British values and educational space. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.; Borba, M.C.; Llinares, S.; Kaiser, G. Will 2020 be remembered as the year in which education was changed? ZDM 2020, 52, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotok, S.; Knight, D.S. Revolving Doors: Cross-Country Comparisons of the Relationship between Math and Science Teacher Staffing and Student Achievement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Transforming Education from Within: Current Trends in the Status and Development of Teachers; World Teachers’ Day; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, P. The teacher pipeline for PETE: Context, pressure points, and responses. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 38, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.; Shah, S.; Sundararajan, S.; Bell, K.G.; Jackson, P.; Aponte-Patel, L.; Sargent, C.; Muniz, E.I.; Oghifobibi, O.; Kresch, M.; et al. Paediatric research’s societal commitment to diversity: A regional approach to an international crisis. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 933–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentassuglia, G. (Ed.) Ethno-Cultural Diversity and Human Rights: Challenges and Critiques; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Gündemir, S.; Ağirdağ, O. Diversity approaches matter in international classrooms: How a multicultural approach buffers against cultural misunderstandings and encourages inclusion and psychological safety. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 1903–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; McKenzie, J.; Watermeyer, B.; Vergunst, R.; Karisa, A.; Samuels, C. We Need to Go Back to Our Schools, and We Need to Make that Change We Wish to See: Empowering Teachers for Disability Inclusion. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. 2022, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keon, D.M. Soft barriers—The impact of school ethos and culture on the inclusion of students with special educational needs in mainstream schools in Ireland. Improv. Sch. 2020, 23, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, B.; Wynen, J.; Kleizen, B. What happens when the going gets tough? Linking change scepticism, organizational identification, and turnover intentions. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1056–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, M.; Nordin, M.; Yepes-Baldó, M.; Romeo, M.; Westerberg, K. Cold wind of change: Associations between organizational change, turnover intention, overcommitment and quality of care in Spanish and Swedish eldercare organizations. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyensare, M.A.; Kumedzro, L.E.; Sanda, A.; Boso, N. Linking transformational leadership to turnover intention in the public sector: The influences of engagement, affective commitment, and psychological climate. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I. School leaders and transformational leadership theory: Time to part ways? J. Educ. Adm. 2016, 54, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, N.; Flaherty, A.; Mannix McNamara, P. Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research. Societies 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Daly, D.; Lafferty, N.; Mannix McNamara, P. The Real Deal: A Qualitative Investigation of Authentic Leadership in Irish Primary School Leaders. Societies 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sitkin, S.B. A critical assessment of charismatic—Transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.S.; Burch, G.S.J. The “dark side” of leadership personality and transformational leadership: An exploratory study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Christie, A.; Hoption, C. Leadership. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Building and Developing the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 183–240. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Downton, J.V. Rebel Leadership: Commitment and Charisma in the Revolutionary Process. The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Saenz, H.R. Transformational leadership. SAGE Handb. Leadersh. 2011, 5, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Collier Macmillan: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, W.; Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes, J.M.; Posner, B.Z. The Leadership Challenge; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. The transformational Model of leadership. In Leading Organisations; Perspectives of a New Era, 2nd ed.; Sage: Riverside, CA, USA, 2010; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman, B. Followership: How Followers are Creating Change and Changing Leaders; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kark, R.; Shamir, B. The Dual Effect of Transformational Leadership: Priming Relational and Collective Selves and Further Effects on Followers. In Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead; Avolio, B.J., Yammarino, F.J., Eds.; JAI Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, P.; Bolat, E.; Nordberg, D.; Wilkin, C. Mirror, mirror on the wall: Shifting leader–follower power dynamics in a social media context. Leadership 2020, 16, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Riehl, C. What do we already know about educational leadership? In A New Agenda for Research in Educational Leadership; Firestone, W.A., Riehl, C., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Montgomery, D.J. The Role of the Elementary School Principal in Program Improvement. Rev. Educ. Res. 1982, 52, 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Camb. J. Educ. 2003, 33, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Transformational leadership: How principals can help reform school cultures. School Eff. School Improv. 1990, 1, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Tomlinson, D.; Genge, M. Transformational school leadership. In International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration; Leithwood, K., Ed.; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 785–840. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. Contributions of transformational leadership to school restructuring. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the University Council for Educational Administration, Houston, TX, USA, 29–31 October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. Leadership for school restructuring. Educ. Adm. Q. 1994, 30, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Leithwood, K. Transformational School Leadership Effects on Student Achievement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2012, 11, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. The evolving role of American principals: From managerial to instructional to transformational leaders. J. Educ. Adm. 1992, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Imran, R.; Irshad, M.K.; Mohamad, N.A.; Khan, M.M. Leadership styles in relation to employees’ trust and organizational change capacity: Evidence from non-profit organizations. Sage Open 2016, 6, 2158244016675396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Instructional and transformational leadership: Alternative and complementary models? J. Educ. Adm. 2014, 42, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounder, J. Quality teaching through transformational classroom leadership. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2014, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.; Saltmarsh, S. It all comes down to the leadership; the role of the school principal in fostering parent-school engagement. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R.S. Students’ help seeking during problem solving: Influences of personal and contextual achievement goals. J. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 90, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. Leading in a Culture of Change; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, K.; Louis, K.S. Restructuring that lasts: Managing the performance dip. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2007, 2, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Finch, K.S.; MacGregor, C. A Comparison of Learning Cultures in Different Sizes and Types. US-China Educ. Rev. A 2012, 2, 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, K.D.; Deal, T.E. How leaders influence the culture of schools. Educ. Leadersh. 1998, 56, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, T.E.; Peterson, K.D. Shaping school culture: The heart of leadership. Adolescence 1999, 34, 802. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, R.S. The culture builder. Educ. Leadersh. 2002, 59, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Smircich, L. Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, S.J. The Principal as Instructional Leader: A Handbook for Supervisor, 2nd ed.; Eye on Education: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stolp, S.; Smith, S.C. Transforming School Culture: Stories, Symbols, Values, and the Leader’s Role.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management: Eugene, OR, USA, 1995; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Renchler, R.S. Student Motivation, School Culture, and Academic Achievement: What School Leaders Can Do; ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management: Eugene, OR, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Pearson, A. The systematic review: An overview. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, M.P.; MacKenzie, B.S.; Moorman, H.R.; Fetter, R. Transformational Leader Behaviors and Their Effects on Followers’ Trust in Leader, Satisfaction, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Leadership Quart. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I.; Eyal, O. Emotional reframing as a mediator of the relationships between transformational school leadership and teachers’ motivation and commitment. J. Educ. Adm. 2017, 55, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, X.; Galand, B. The multilevel impact of transformational leadership on teacher commitment: Cognitive and motivational pathways. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 38, 703–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraku, Z.H.; Hoxha, L. Impact of transformational and transactional attributes of school principal leadership on teachers’ motivation for work. Front. Educ. Res. 2021, 6, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Eliophotou-Menon, M.; Ioannou, A. The link between transformational leadership and teachers’ job satisfaction, commitment, motivation to learn, and trust in the leader. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2016, 20, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hauserman, C.P.; Stick, S.L. The Leadership Teachers Want from Principals: Transformational. Can. J. Educ. 2013, 36, 184–203. [Google Scholar]

- Karabağ Köse, E.; Güçlü, N. Examining the Relationship between Leadership Styles of School Principals, Organizational Silence, and Organizational Learning. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2017, 9, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, S.S. The role of transformational school leadership in promoting teacher commitment: An antecedent for sustainable development in South Africa. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2019, 10, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.D.; Kuo, C.T. Principals’ transformational leadership and teachers’ work motivation: Evidence from elementary schools in Taiwan. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2019, 1, 898. [Google Scholar]

- Muliati, L.; Asbari, M.; Nadeak, M.; Novitasari, D.; Purwanto, A. Elementary School Teachers Performance: How the Role of Transformational Leadership, Competency, and Self-Efficacy? Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2022, 3, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nir, A.; Piro, P.L. The added value of improvisation to effectiveness-oriented transformational leadership. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2016, 25, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, B.P. Transformational Leadership of Principals in Middle Schools employing the Teaming Model. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.; Tuytens, M.; Devos, G.; Kelchtermans, G.; Vanderlinde, R. Transformational school leadership as a key factor for teachers’ job attitudes during their first year in the profession. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, M.; Inandi, B.; Colak, A.L. Do leadership styles influence organizational health? A study in educational organizations. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2015, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windlinger, R.; Warwas, J.; Hostettler, U. Dual effects of transformational leadership on teacher efficacy in close and distant leadership situations. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeriah, J.; Yan Piaw, C.; Yan Li, S.; Enamul Hoque, K. Teachers’ perception on the relationships between transformational leadership and school culture in primary cluster schools. Malays. Online J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 5, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngang, T.K. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on School Culture in Male’ Primary Schools Maldives. Procedia Soc. 2011, 30, 2575–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyer, A. Trust in school principals: Teachers’ opinions. EduLearn 2017, 6, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.; Redzuan, M. The relationship between principal’s leadership styles and teacher’s organizational trust and commitment. J. Life Sci. 2012, 9, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, P. Why trust the head? Key practices for transformational school leaders to build a purposeful relationship of trust. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2014, 17, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. How Does Principals’ Transformational Leadership Impact Students’ Modernity? A Multiple Mediating Model. Educ. Urban Soc. 2021, 53, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Senécal, C.; Guay, F.; Marsh, H.; Dowson, M. The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST). J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, O.; Roth, G. Principals’ Leadership and Teachers’ Motivation. J. Educ. Admin. 2011, 49, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensch, M. Teacher Participation in Extracurricular Activities: The Effect on School Culture; Hamline University: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kark, R.; Shamir, B. The Dual Effect of Transformational Leadership: Priming Relational and Collective Selves and Further Effect on Followers. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2013, 5, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Corey, C.A. Study of Instructional Scheduling, Teaming, and Common Planning in New York State Middle Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Minckler, C.H. School leadership that builds teacher social capital. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyve, C.; Daly, A.; Vandecandelaere, M.; Meredith, C.; Hannes, K.; De Fraine, B. More than a mentor: The role of social connectedness in early career and experienced teachers’ intention to leave. J. Prof. Cap. 2016, 1, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. Successful school leadership: Case studies of four Singapore primary schools. J. Educ. Adm. 2016, 54, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honingh, M.; Hooge, E. The effect of school-leader support and participation in decision making on teacher collaboration in Dutch primary and secondary schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekçi, A.K.; Tekin, B. The examination of the relationship between creativity and work environment factors with research in white-goods sector in Turkey. Öneri Derg. 2011, 9, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.K. What is transformational leadership? A model for motivating innovation cio.com. Available online: https://www.cio.com/article/228465/what-is-transformational-leadership-a-model-for-motivating-innovation.html (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. J. Occup. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatcan, M.; Arslan, P.; Balci, C. The mediating effect of teacher self-efficacy regarding the relationship between transformational school leadership and teacher agency. Educ. Stud. 2021, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Tineh, A.; Khasawneh, S.; Al-Omari, A. Kouzes and Posner’s transformational leadership model in practice: The case of Jordanian schools. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 648–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N.; Yousafzai, I.K.; Jan, S.; Hashim, M. The impact of training and development on employees performance and productivity a case study of United Bank Limited Peshawar City, KPK, Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. 2014, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durukan, H. The visioner role of school administrator. KEFAD 2006, 7, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar, N.M.; Daly, A.J.; Sleegers, P.J.C. Occupying the principal position: Examining relationships between transformational leadership, social network position, and schools’ innovative climate. Educ. Adm. Q. 2010, 46, 623–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A. Transforming School Culture: How to Overcome Staff Division; Solution Tree Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ciric, M.; Jovanovic, D. Student engagement as a multidimensional concept. WLC 2016, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. The New Lives of Teachers, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P. Successful School Leadership. 2016. Available online: https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/EducationDevelopmentTrust/files/a3/a359e571-7033-41c7-8fe7-9ba60730082e.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Pajarianto, H.; Kadir, A.; Galugu, N.; Sari, P.; Februanti, S. Study from home in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of religiosity, teacher, and parents support against academic stress. Int. Res. Assoc. Talent. Dev. Excell. 2020, 12, 1792–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Geijsel, F.; Sleegers, P.; Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Transformational Leadership Effects on Teachers’ Commitment and Effort toward School Reform. J. Educ. Admin. 2003, 41, 228–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness; Atlantic Monthly Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K. The Evolution of Leadership—A Look at Where Leadership Is Heading; Centre for Values-Driven Leadership, Benedictine University: Lisle, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. Transformational leadership in education: A review of existing literature. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2017, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chegini, M.G. The relationship between organizational culture and staff productivity in public organizations. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulford, B.; Bishop, P. Leadership in Organizational Learning and Student Outcomes (LOLSO) Project; University of Tasmania: Launceston, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Explaining variation in teachers’ perceptions of principals’ leadership: A replication. J. Educ. Adm. 1997, 35, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansoy, R. Transformational School Leadership: Predictor of Collective Teacher Efficacy. Sakaraya Univ. J. Educ. 2020, 10, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, S.; Bektas, F. The relationship between school culture and leadership practices. Egit. Arast. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2013, 52, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Quin, J.; Deris, A.; Bischoff, G.; Johnson, J.T. Comparison of transformational leadership practices: Implications for school districts and principal preparation programs. Educ. Leadersh. 2015, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Hopkins, D. Distributed Leadership and Organizational Change: Reviewing the Evidence. J. Educ. Change 2007, 8, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerr, T.R. The Art of School Leadership; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Relevance | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Of very high relevance to TSL and for specific focus | 17 |

| Level 2 | Of high relevance to this review but not for specific focus | 44 |

| Level 3 | Of relevance to this review but not for specific focus | 24 |

| Country | Number | Country | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 2 | Kuwait | 1 |

| Belgium | 2 | Malaysia | 3 |

| Canada | 3 | Mongolia | 1 |

| Chile | 1 | Pakistan | 1 |

| China | 6 | Philippines | 1 |

| Cyprus | 2 | Singapore | 1 |

| India | 1 | Switzerland | 1 |

| Indonesia | 1 | South Africa | 2 |

| Iran | 1 | Taiwan | 1 |

| Ireland | 6 | Turkey | 16 |

| Israel | 8 | United Arab Emirates | 1 |

| Jamaica | 1 | United Kingdom | 4 |

| Japan | 1 | Unites States of America | 25 |

| Jordan | 1 | China and US | 1 |

| Year | Number | Year | Number | Year | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1 | 2012 | 8 | 2018 | 9 |

| 2004 | 1 | 2013 | 3 | 2019 | 8 |

| 2006 | 1 | 2014 | 4 | 2020 | 10 |

| 2007 | 1 | 2015 | 8 | 2021 | 9 |

| 2010 | 1 | 2016 | 12 | 2022 | 4 |

| 2011 | 7 | 2017 | 9 | Total | 95 |

| Record | Author(s) | Year | Country | Study/Book | Participant/Study Nos | Peer-Reviewed Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [74] | Berkovic, I.; Eyal, O. | 2017 | Israel | Quantitative Study | Participants: 639 | Journal of Educational Administration |

| 2 [75] | Dumay, X.; Galand, B. | 2012 | Belgium | Quantitative Study | Participants: 660 | British Educational Research Journal |

| 3 [76] | Duraku, Z.H.; Hoxha, L. | 2021 | Kosovo | Quantitative Study | Participants: 357 | Frontiers in Education |

| 4 [77] | Eliophotou-Menon, E.M.; Ioannou, A. | 2016 | Cyprus | Literature Review | Studies: 21 | Academy of Educational Leadership Journal |

| 5 [78] | Hauserman, C.; Stick, S.L. | 2013 | Canada | Qualitative and Quantitative Study | Participants: 9 ≈340 | Canadian Journal of Education |

| 6 [79] | Karabag Kose, E.; Guçlu, N. | 2017 | Turkey | Quantitative Study | Participants: 591 | International Online Journal of Educational Sciences |

| 7 [80] | Khumalo, S.S. | 2019 | South Africa | Quantitative Study | Participants: 95 | Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education |

| 8 [81] | Lee, Y.D.; Kuo, C.T. | 2019 | Taiwan | Quantitative study | Participants: 430 | International Journal of Organisational Innovation |

| 9 [82] | Muliati, L.; Asbari, M.; Nadeak, M.; Novitasari, D.; Purwanto, A. | 2022 | Indonesia | Quantitative Study | Participants: 210 | International Journal of Social and Management Studies |

| 10 [83] | Nir, A.; Piro, P.L. | 2016 | Israel | Quantitative Study | Participants: 756 | International Journal of Educational Reform |

| 11 [84] | Plichta, B.P. | 2018 | United States of America | Qualitative study | Participants: 15 | Doctoral study |

| 12 [85] | Thomas, L.; Tuytens, M.; G. Devos, G.; Kelchtermans, G.; Van-derlinde, R. | 2020 | Belgium | Quantitative Study | Participants: 292 | Educational Management Administration and Leadership |

| 13 [86] | Toprak, M.; Inandi, B.; Colak, A.L. | 2015 | Turkey | Quantitative Study | Participants: 151 | International Journal of Social and Management Studies |

| 14 [87] | Veeriah, J.; Yan Piaw, C.; Yan Li, S.; Enamul Hoque, K. | 2017 | Malaysia | Quantitative Study | Participants: 331 | Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management |

| 15 [88] | Windlinger, R.; Warwas, J.; Hostettler, U. | 2020 | Switzerland | Quantitative Study | Participants: 1702 | School Leadership and Management |

| 1. | Bass [39] |

|

| 2. | Podsakoff et al. [73] |

|

| 3. | Sun and Leithwood [54] |

|

| 4. | Kouzes and Posner [41] |

|

| The Impact of Transformational School Leadership in Primary, Elementary, and Early Middle Schools on School Staff and School Culture from the Studied Literature | ||

|---|---|---|

| Achievement | Autonomous motivation | Autonomy |

| Balance | Capacity for problem-solving | Change adaptation |

| Collaboration | Collegiality | Commitment |

| Competence | Concentration | Confidence |

| Cooperation | Creativity | Decreased organisational silence |

| Educational outcomes | Efficacy | Expression and attachment |

| Empowerment | Enjoyment | Excellence |

| Group capability | Group goal creation | Ideas exchange |

| Identification | Improvisation | Individual needs |

| Innovation | Inspiration | Intuition |

| Instructional improvement | Involvement | Leadership capacity |

| Lower teacher absenteeism | Open communication | Organisational commitment |

| Organisational flexibility | Organisational health | Organisational learning |

| Participation | Peer support | Performance |

| Positive learning culture | Productivity | Professional support |

| Punctuality | Reduced organisational silence | Reflection |

| Relationships | Respect and appreciation | Responsibility |

| Role modelling | Satisfaction | School effectiveness |

| School improvement | Self-development | Self-efficacy |

| Self-evaluation | Shared vision | Spontaneity |

| Staff retention | Sustainable development | Team development |

| Teachers’ capacity | Trust | Change implementation |

| Unity | Vision creation | Work level motivation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilson Heenan, I.; De Paor, D.; Lafferty, N.; Mannix McNamara, P. The Impact of Transformational School Leadership on School Staff and School Culture in Primary Schools—A Systematic Review of International Literature. Societies 2023, 13, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060133

Wilson Heenan I, De Paor D, Lafferty N, Mannix McNamara P. The Impact of Transformational School Leadership on School Staff and School Culture in Primary Schools—A Systematic Review of International Literature. Societies. 2023; 13(6):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060133

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilson Heenan, Inez, Derbhile De Paor, Niamh Lafferty, and Patricia Mannix McNamara. 2023. "The Impact of Transformational School Leadership on School Staff and School Culture in Primary Schools—A Systematic Review of International Literature" Societies 13, no. 6: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060133

APA StyleWilson Heenan, I., De Paor, D., Lafferty, N., & Mannix McNamara, P. (2023). The Impact of Transformational School Leadership on School Staff and School Culture in Primary Schools—A Systematic Review of International Literature. Societies, 13(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060133