Abstract

Multicultural education has been widely recognized as an educational approach to deal with social and cultural diversity towards a more inclusive and just society. Conventional perspectives tend to assume that multicultural education would be of greater interest as a research topic in countries with growing levels of diversity. However, based on a macro-phenomenological perspective, this study accounts for influences from the wider institutional environment that gives collective meaning and value to legitimize multiculturalism as an academic discourse topic. Using a cross-national research design, this study examined the national-level characteristics associated with the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education. Scholarly articles on multicultural education published in the field of education by 2020 were collected using the research platform Web of Science. A total of 105 countries with 14,220 articles were analyzed using multiple regression analysis. Our results showed that countries with stronger ties to global civil society were more likely to have articles on multicultural education, indicating a higher institutionalization level of relevant academic discourse within the country. These findings suggest that the popularity of multicultural education as an academic discourse may not solely be in response to national-level societal demands but rather may be an institutional embodiment of universalistic norms and values.

1. Introduction

Multicultural education is widely perceived as a means of enhancing multicultural awareness and promoting social unity. Despite being a contested concept with multiple meanings, it is commonly understood as an educational approach that addresses social and cultural diversity within a specific country, with the goal of fostering a more inclusive and just society [1,2]. The significance of cultural diversity and multiculturalism in education has been magnified, especially in the context of heightened global mobility and interconnectivity [3,4]. Conventional perspectives tend to assume that societal needs contribute to the popularity of multicultural education as an academic discourse [5,6]. Specifically, it is often expected that, in a country with high levels of racial, ethnic, linguistic, and/or religious diversity, more research on multicultural education should take place, with the aim of promoting social harmony and cohesion. While such functionalist perspectives provide useful insights into the cross-national variation of multicultural education as an academic discourse, they often have difficulty in accounting for influences from the wider environment.

The present study endeavors to provide an alternative conceptualization of the cross-national formation of academic discourse surrounding multicultural education. We argue that the rising popularity of multicultural education as an academic discourse across countries is a phenomenon that is embedded in the larger institutional environment, where the collective value of multiculturalism is taken for granted as a legitimate discourse topic [7,8]. Unlike the prevailing belief that academic research topics emerge from rational choices in response to specific societal needs, our alternative perspective posits that the increasing acceptance of multicultural education as an academic discourse has become an institution which legitimacy is closely associated with the evolving reconceptualization of citizenship and human rights in global civil society [9,10,11].

World polity theory elucidates the crucial role of cultural and legitimacy-based institutional forces in driving social change. According to this theory, institutions are defined as “cultural rules giving collective meaning and value to particular entities and activities” [7] (p. 67), while institutionalization refers to “the process by which a given set of units [individuals and other social entities] and a pattern of activities come to be normatively and cognitively held in place, and practically taken for granted as lawful” [7] (p. 68). By embracing this perspective, we recognize that patterns of activity and the entities engaged in them are socially constructed within a broader framework of rules and norms [12,13]. Adopting this theoretical lens within the global context of academic discourse formation and development, we posit that the growing emphasis on multicultural education as an academic discourse in recent decades is deeply rooted in the larger institutional environment, where the collective meaning and value attributed to multiculturalism are accepted as a legitimate subject of scholarly inquiry.

Multicultural Education as Academic Discourse

This study presents three distinct perspectives aimed at providing valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education within countries worldwide. Three perspectives include a sociocultural perspective, an international economic perspective, and a world polity perspective1. By engaging in a thorough examination of these perspectives, a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the various factors that shape the development of academic discourse surrounding multicultural education can be achieved.

First, the most widely accepted account is a sociocultural perspective, which posits that the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education is a response to the social and cultural diversity within a country. According to this perspective, the high level of interest in multicultural education as a discourse topic reflects a scholarly effort to address the concrete societal demands of a particular country [16,17]. During the past decades, increased global mobility has led to a surge in the number of migrants, resulting in unprecedented levels of diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, religion, and language within countries [18]. As a result, many countries face the challenge of promoting social cohesion, and academic discourse on multicultural education has emerged as a way to address this challenge by responding to concrete societal needs within a country.

Specifically, in countries with diverse ethnolinguistic populations, research on multicultural education is expected to be active in order to address issues related to cross-cultural understanding and communication. Although definitions may vary, it is generally agreed that multicultural education aims to foster a more equitable and inclusive society for all, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, or religion [19,20,21]. Multicultural education, viewed from a sociocultural perspective, can be regarded as an effective means of accommodating cultural diversity and promoting social cohesion. Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that academic discourse on multicultural education is more vibrant in countries with a high level of sociocultural diversity (Hypothesis 1). The central assumption underlying this perspective is a close relationship between the formation of academic discourse and the concrete societal conditions prevailing within a given country.

Secondly, from an international economic perspective, the importance placed on multicultural education within a country may be closely tied to its economic relations with other countries. As economic interdependency between countries intensifies, promoting intercultural competence is often seen as a rational and functional response to the increasing demands of the global economic system. From this perspective, understanding cross-cultural differences is essential for addressing practical issues that arise in international economic activities [22,23]. The assumption is that communication, persuasion, and decision making are profoundly culture-dependent and deeply rooted in cultural assumptions and attitudes [24]. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that, in countries with a strong focus on international economic activities, there would be greater attention paid to multicultural education as a means of improving sensitivity to different cultures and facilitating such activities.

For instance, countries actively involved in international trade and experiencing substantial inflows of foreign investment are more likely to place greater emphasis on promoting multicultural education. This emphasis is driven by the recognition that multicultural education plays a vital role in comprehending and respecting diverse cultural backgrounds, as well as developing the necessary intercultural competencies for successful participation in the global market. In such contexts, academic discourse on multicultural education becomes instrumental in fostering an understanding of cultural diversity and nurturing the skills needed to navigate international economic activities. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that academic discourse on multicultural education is more vibrant in countries which economies are highly dependent on international economic relations (Hypothesis 2). This perspective aligns with the sociocultural perspective in emphasizing the association between the formation of academic discourse and the specific societal conditions prevalent within a given country.

Finally, a world polity perspective emphasizes the influence of the wider institutional environment on the development of an academic discourse on multicultural education. According to this perspective, “the world polity is constituted by a distinct culture—a set of fundamental principles and models, mainly ontological and cognitive in character, defining the nature and purposes of social actors and action” [25] (p. 14). This perspective posits that countries are expanded and empowered by embedded actors who are tied to the wider world order, bringing in the cultures of the wider system that are rationalized as best practices [7]. As discussed by Meyer [26], while discussions on globalization have mainly focused on increasing economic exchanges such as trade and investment between countries, these changes are closely related to shifts in the social consciousness of world society. The Second World War led to the emergence of the dangers of a nation-centric perspective, prompting a rise in the individual person within a global context [26,27]. Furthermore, global civil society and its role in expanding the human rights movement paved the way for multicultural education to be legitimized and institutionalized under the canopy of the modern world system [28,29]. From this viewpoint, the development of academic discourse is constantly influenced by institutional dynamics of the global cultural environment, the world polity.

A world polity perspective conceptualizes the world as a society that has a significant impact on countries and accounts for the impetus for global action with a transnational sector. Within this perspective, world society, functioning as a broad cultural order, drives processes of global diffusion, with international organizations serving as prime carriers of its cultural core. These organizations, including international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) operating at the global level, reflect a global cultural framework in their structures, purposes, and operations [30,31]. Previous studies suggested that the proximity between a country and global civil society can be gauged not only through the degree of connectivity via global networks such as the Internet but also through factors such as the enrollment rate in higher education [32,33]. From a world polity perspective, academic discourse development within a country is understood as an institutional embodiment of world-level cultural norms and values rather than an instrumental means to address the concrete needs of a society. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that academic discourse on multicultural education is more vibrant in countries with more ties to global civil society (Hypothesis 3). Taking a macro-phenomenological standpoint, this perspective accounts for influences from the global institutional environment that gives collective meaning and value to legitimize multiculturalism as a subject of academic discourse.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a cross-national research design to examine what factors are associated with the development of academic discourse on multicultural education across countries. Data on academic discourse related to multicultural education were collected from Web of Science, a prominent research platform, which allowed for a cross-national analysis of scholarly articles on the topic. Articles that included one or more of the keywords, such as multicultural, intercultural, global citizenship, culturally responsive, culturally relevant, diversity, and their derivatives in the title, abstract, or keywords were considered scholarly articles on multicultural education. By the year 2020, a total of 14,220 relevant articles were published in the field of education from 105 countries. In this study, the number of articles was log-transformed and used as a dependent variable, serving as a proxy for the extent to which academic discourse on multicultural education is established within a country.

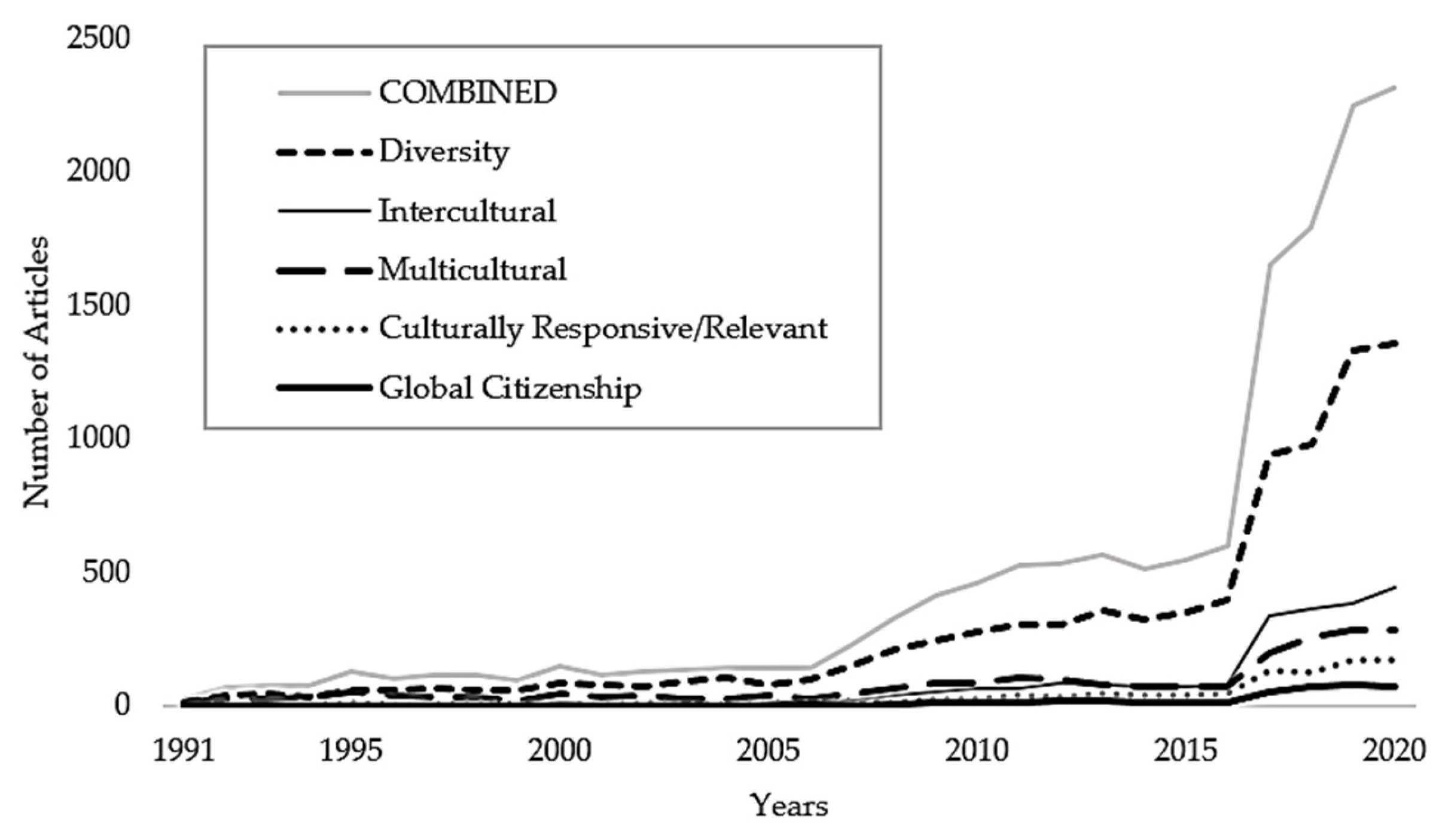

As a preliminary analysis, the visual presentations in Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide compelling evidence of the growing prominence of multicultural education as a subject of academic discourse over time. Figure 1 illustrates a dramatic increase in the number of articles published on multicultural education, as indicated by the corresponding keyword search. Notably, similar patterns of growth are observed across all the keywords examined in this study. The surge in the number of publications underscores the heightened scholarly interest and engagement with the topic of multicultural education in the field of education.

Figure 1.

Number of articles on multicultural education by keyword, 1991–2020.

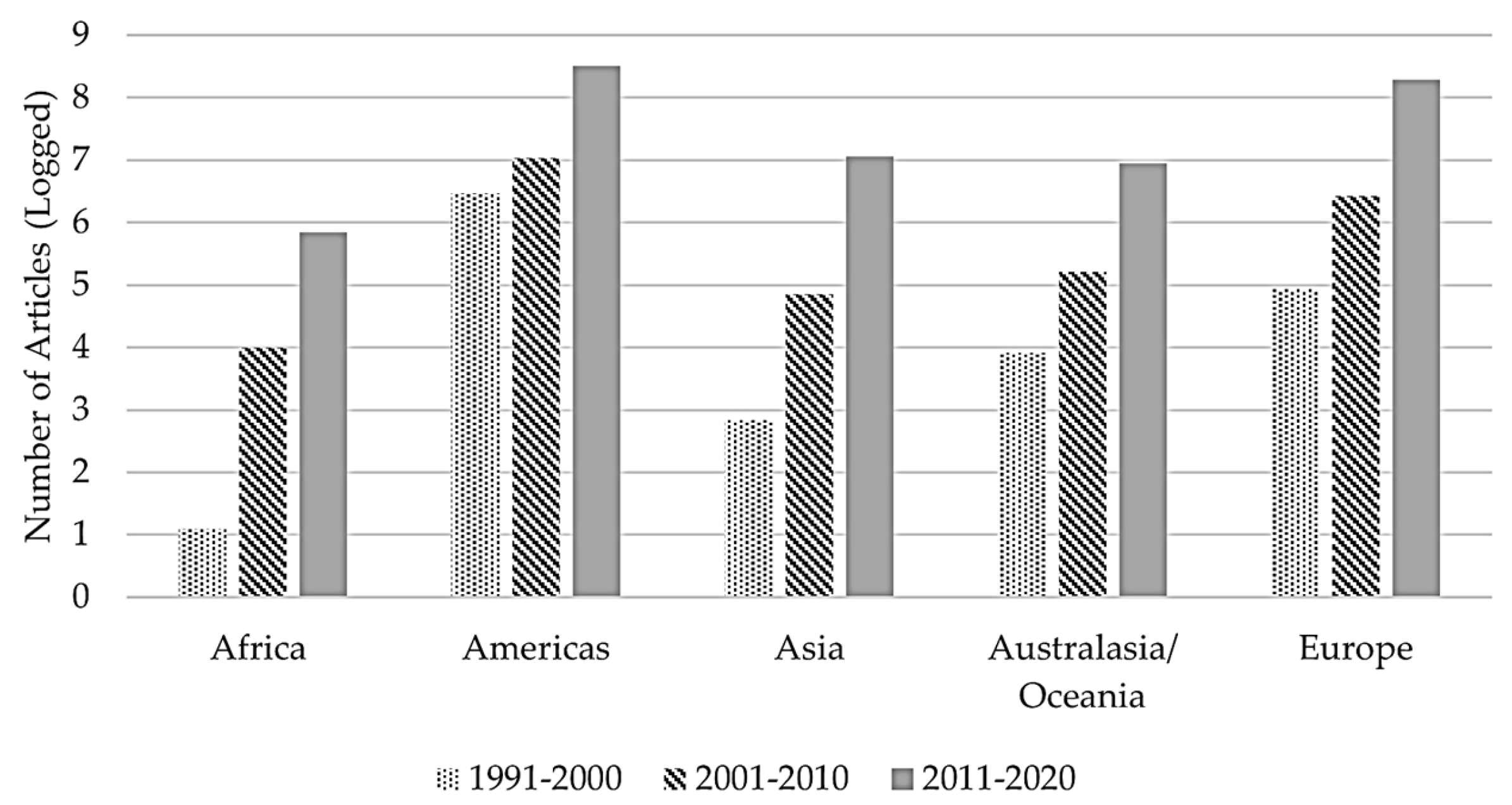

Figure 2.

Number of articles (logged) on multicultural education by region. Africa (n = 27); the Americas (n = 22); Asia (n = 37); Australasia/Oceania (n = 6); Europe (n = 46).

Figure 2, on the other hand, offers a comprehensive view of the logged number of articles on multicultural education categorized by region spanning three decades. The data depicted in Figure 2 reveal a consistent and significant rise in the quantity of articles focusing on multicultural education across various regions of the world. These regions include Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australasia/Oceania, and Europe. The expansive reach of multicultural education discourse is apparent in the upward trends observed across these diverse regions.

Based on the trends observed in Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is reasonable to argue that academic discourse on multicultural education has expanded globally over the past 30 years. The increase in scholarly publications demonstrates a heightened recognition of the significance and relevance of multicultural education as an academic field of inquiry.

A range of national-level characteristics were considered for the factor analysis, as per the three hypotheses mentioned previously. Ethnic and cultural fractionalizations, obtained from Fearon [34], were used as indices of a country’s diversity score, with the scores ranging from zero for no fractionalization to near one for high fractionalization. In line with our second hypothesis, we included data on international trade and foreign direct investments, expecting them to constitute a single factor that represents a country’s dependency on the global market. Specifically, international trade refers to the sum of a country’s exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of gross domestic product, while foreign direct investment denotes the net flows of foreign direct investment as a percentage of gross domestic product [35]. Data on the number of INGOs that individuals or organizations belong to in a given country were obtained from the Union of International Associations [36], with the logged number used to reduce data skewness. Higher education enrollments were measured as the gross enrollment rate in tertiary education, while Internet users were defined as individuals using the Internet as a percentage of the population [35]. Lastly, the log-transformed total population and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita were included in the model as control variables for the regression analysis. Descriptive statistics for the variables and characteristics used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the variables/characteristics.

Utilizing the national-level characteristics, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted, resulting in the derivation of three factors, as presented in Table 2. The characteristics that clustered for the same factor indicate that factor 1 represented linkages to global civil society (LINK), factor 2 pertained to sociocultural diversity (DIV), and factor 3 concerned international economic relations (INTL), all of which were used as independent variables in this study.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis of national-level characteristics: factor loadings.

Drawing upon the outcomes of the factor analysis outlined in Table 2, several reasonable assumptions can be made. Firstly, it is plausible to assert that the level of sociocultural diversity within a country bears a close relationship with its cultural and ethnic fractionalization. Secondly, the degree to which a country engages in international economic activities exhibits a strong association with its participation in international trade and the capacity to attract foreign direct investment. Lastly, the extent of a country’s linkages to global civil society can be approximated by various measurable characteristics, including memberships in INGOs, higher education enrollments, and the number of Internet users.

3. Results

Table 3 presents the results of regression analyses explaining the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education. Specifically, two models were analyzed. Model 1 explains the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education as a function of our main explanatory variables extracted through the factor analysis, while Model 2 examines whether this association persists when considering the effect of the control variables.

Table 3.

Regressions explaining the number of articles on multicultural education.

First of all, a noticeable pattern was that neither sociocultural diversity nor international economic relations was significantly associated with the formation of academic discourse on multicultural education2. The regression models yielded statistically insignificant effects for these variables. This finding is noteworthy, considering the prevailing assumptions that multicultural education serves as a practical approach in addressing specific societal needs within individual countries. The independence of academic discourse formation on multicultural education from a country’s sociocultural diversity and international economic relations introduces the possibility that the popularity of multicultural education as an academic discourse may not solely arise as a functional response.

The only variable that consistently and strongly showed a significant main effect was linkages to global civil society, which remained statistically significant even after controlling for population and GDP per capita (Model 2). The results unequivocally indicated that countries with stronger ties to global civil society were significantly more inclined to have an academic discourse on multicultural education.

Overall, the results presented in Table 3 provide robust support for Hypothesis 3, which is grounded in the world polity perspective. The findings demonstrate a strong and consistent association between individual countries’ linkages to global civil society and the development of academic discourse on multicultural education. In contrast, our data did not support Hypothesis 1, based on the sociocultural perspective, or Hypothesis 2, derived from the international economic perspective, as no significant main effect was observed in either of the models. These findings shed light on the dynamics of academic discourse formation and underscore the pivotal role of linkages to global civil society in impacting the prominence of multicultural education as a subject of academic discourse.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Multicultural education is commonly regarded as a research topic of heightened significance in countries grappling with escalating societal diversity, as they face a stronger impetus to address these issues. Previous studies, particularly those within the field of education, have primarily concentrated on the practical value of multicultural education, adopting a functionalistic perspective. These studies assert that multicultural education is a timely and relevant concern, given the intensified demographic shifts within societies and the expanding exchanges and collaborations between countries. Their emphasis on the importance of multicultural education research is rooted in the increasing international migration and interdependency, underpinned by a functional assumption.

The present study challenges this prevailing assumption by proposing an alternative explanation for the variations in the institutionalization level of multicultural education research across countries. Drawing from the world polity perspective, our hypothesis posits that countries with stronger ties to global civil society are more likely to exhibit a higher level of institutionalization in academic discourse on multicultural education. The data utilized in this study support our hypothesis and provide empirical evidence of the effect of global civil society ties on the institutionalization process. The main findings presented in this study align, to a considerable extent, with previous research grounded in the world polity perspective that explores the institutionalization of world culture. By empirically examining the institutionalization of multicultural education as an academic discourse on a global scale, this study further reinforces the robust explanatory capacity of world polity theory.

Proposing a novel conceptualization of the variations in multicultural education research across countries, we argue that the popularity of multicultural education as an academic discourse may not solely be in response to national-level societal demands but may also be an institutional embodiment of universalistic norms and values. This interpretation views active research on multicultural education as a legitimate institutionalized product of the changing concept of citizenship and human rights in global civil society. From a functionalistic standpoint, researchers are often intrigued by the number of immigrants and the rate at which their population grows, as these factors are seen as indicators of societal demands for multicultural education. In contrast, a world polity perspective asserts that, regardless of the quantity of individuals categorized as minorities, serious consideration of equity and continued effort to accommodate diversity are imperative, as multicultural education has become a highly rationalized discourse. From this perspective, the immediate usefulness of multicultural education within individual countries may not be the primary concern. Therefore, we suggest that influences from the wider institutional environment must be taken into account when analyzing the phenomenon of multicultural education as a rapidly growing academic discourse.

It seems that the discourse surrounding multicultural education worldwide has been increasingly linked to the expanded concept of citizenship, which places great emphasis on the individual as a primordial member of global civil society. This emphasis on the individual’s role is prominently highlighted within the institutional environment of the modern world system. The discourse on multicultural education appears to be grounded in the notion of the individual theorized as a member of transnational communities, where the significance of personal identity is celebrated based on the prevailing world cultural values. Consequently, the formation and development of academic discourse on multicultural education can largely be understood as an embodiment of universalistic world models and principles that underscore the ontological status of the individual.

The findings of this study suggest that multicultural education, having attained a high degree of institutional legitimacy, has become an integral component of academic discourse across many countries. As it has emerged as a core element of the global educational model, it is imperative for researchers to engage in concerted efforts to develop comprehensive and elaborate theories grounded in robust empirical evidence. Moreover, to prevent multicultural education discourse from being reduced to normative or hortatory discussions, it is crucial to examine and apply it in local contexts, which may necessitate more locally specific perspectives. Given the distinct historical and cultural trajectories of individual countries, the implementation of fundamental cultural principles varies, accompanying processes of adaptation. Therefore, conducting more localized analyses and applications of multicultural education is crucial to better understand its efficacy and effectiveness in addressing local diversity and social justice concerns. This requires research that is delicately tailored for local implementation.

This study had some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, our examination of articles on multicultural education was confined to Web of Science, which exhibits high selectivity. Consequently, the results obtained from this web database search tool may not encompass the entirety of the published articles on multicultural education worldwide. Expanding the scope of web databases employed would yield more extensive results. Furthermore, it is important to note that, while the data used in this study included articles published in 17 languages, there is a possibility of overrepresentation of articles written in English. Lastly, our analysis of research on multicultural education relied on six keywords and their derivatives to organize the countries for analysis3. Future research could benefit from exploring a broader range of keywords when collecting scholarly articles on multicultural education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-K.C. and S.-H.H.; Formal analysis, S.L.; Methodology, Y.-K.C. and S.-H.H.; Project administration, S.L.; Supervision, Y.-K.C.; Visualization, S.L.; Writing—original draft, S.L.; Writing—review & editing, Y.-K.C. and S.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study are publicly available. The fractionalization indices employed in this study were retrieved from Fearon [34]. The data on INGO memberships were obtained from the Union of International Associations [36]. The remaining variables used in this study, namely international trade, foreign direct investment, higher education enrollments, Internet users, population, and GDP per capita, all as of the year 2020, can be accessed from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators [35].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The present study’s three hypotheses and methodology design were developed based on the previous works of two of the authors, namely [14,15]. |

| 2 | An additional analysis was undertaken to explore the potential moderating effects of other variables on the significant main effect observed in Model 2. The results revealed a negative interaction effect (p ≤ 0.1) between linkages to global civil society and international economic relations, in addition to the positive main effect of linkages to global civil society (p ≤ 0.01). This finding suggests that countries with lower levels of practical interests, such as investment and trade, with other countries tend to be more receptive to world culture and cultural principles. This tendency implies that the institutionalization of multicultural education as an academic discourse may not be solely contingent on concrete societal conditions but rather represents a symbolic reflection of global models and principles. |

| 3 | In the first author’s thesis, a cross-national analysis, using a similar design and variables to the present study, was conducted to examine the development of academic discourse on multicultural education from 2007 to 2016. The thesis employed keywords such as multicultural, intercultural, cultural diversity, culturally responsive, culturally inclusive, culturally relevant, culturally sustaining, minority, equity, social justice, and their derivatives to collect relevant articles. Notably, the countries identified through this process and the results of the regression analysis were largely consistent with those of the present study. |

References

- Banks, J.A. Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. New directions in multicultural education: Complexities, boundaries, and critical race theory. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, 2nd ed.; Banks, J.A., Banks, C.A.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A.; Banks, C.A.M. Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rivière, F. UNESCO World Report: Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue, 1st ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, S. Multicultural education in the United Kingdom. In The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education, 1st ed.; Banks, J.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Tsolidis, G. Australian multicultural education: Revisiting and resuscitating. In The Education of Diverse Student Populations: A Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Wan, G., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Krücken, G.; Drori, G.S. World Society: The Writings of John W. Meyer, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M.; Ramirez, F.O. World society and the nation-state. Am. J. Sociol. 1997, 103, 144–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrey, O. Citizenship education and the Ajegbo report: Re-imagining a cosmopolitan nation. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2008, 6, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C.J.; Meyer, J.W.; Hosoki, R.I.; Drori, G.S. Constitutions in world society: A new measure of human rights. In Constitution-Making and Transnational Legal Order, 1st ed.; Shaffer, G., Ginsburg, T., Halliday, T.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, F.O.; Bromley, P.; Russell, S.G. The valorization of humanity and diversity. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 2009, 1, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, 1st ed.; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jepperson, R.L.; Meyer, J.W. Institutional Theory: The Cultural Construction of Organization, States, and Identities, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Y.-K.; Ham, S.-H. The institutionalization of multicultural education as a global policy agenda. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2014, 23, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.-K.; Ham, S.-H.; Yang, K.-E. Multicultural education policy in the global institutional context. In Multicultural Education in Glocal Perspectives: Policy and Institutionalization, 1st ed.; Cha, Y.-K., Gundara, J., Ham, S.-H., Lee, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Allemann-Ghionda, C. From intercultural education to the inclusion of diversity: Theories and policies in Europe. In The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education, 1st ed.; Banks, J.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, A.; Awang-Hashim, R.; Noman, M. Defining intercultural education for social cohesion in Malaysian context. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 2017, 19, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, H.; Castles, S.; Miller, M.J. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 6th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C. Genres of research in multicultural education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2001, 71, 171–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killick, D. Critical intercultural practice: Learning in and for a multicultural globalizing world. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 8, 1422–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeter, C.E.; Grant, C.A. Making Choices for Multicultural Education: Five Approaches to Race, Class and Gender, 6th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, F.; Hampden-Turner, C. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, E. The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business, 1st ed.; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations Since 1875, 1st ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W. World models, national curricula, and the centrality of the individual. In School Knowledge in Comparative and Historical Perspective: Changing Curricula in Primary and Secondary Education, 1st ed.; Benavot, A., Braslavsky, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.J.; Meyer, J.W. The profusion of individual roles and identities in the postwar period. Sociol. Theory 2002, 20, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, F.O.; Suárez, D.; Meyer, J.W. The worldwide rise of human rights education. In School Knowledge in Comparative and Historical Perspective: Changing Curricula in Primary and Secondary Education, 1st ed.; Benavot, A., Braslavsky, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui, K.; Wotipka, C.M. Global civil society and the international human rights movement: Citizen participation in human rights international nongovernmental organizations. Soc. Forces 2004, 83, 587–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. World culture in the world polity: A century of international non-governmental organization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapp, M. Empowerment for individual agency: An analysis of international organizations’ curriculum recommendations. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2019, 17, 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Schofer, E. The university in Europe and the world: Twentieth century expansion. In Towards a Multiversity? Universities between Global Trends and National Traditions, 1st ed.; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2006; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schofer, E.; Meyer, J.W. The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, J.D. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataBank: World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/ (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations 2020–2021; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).