Introducing “Trans~Resistance”: Translingual Literacies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Raciolinguistic Discourses in Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

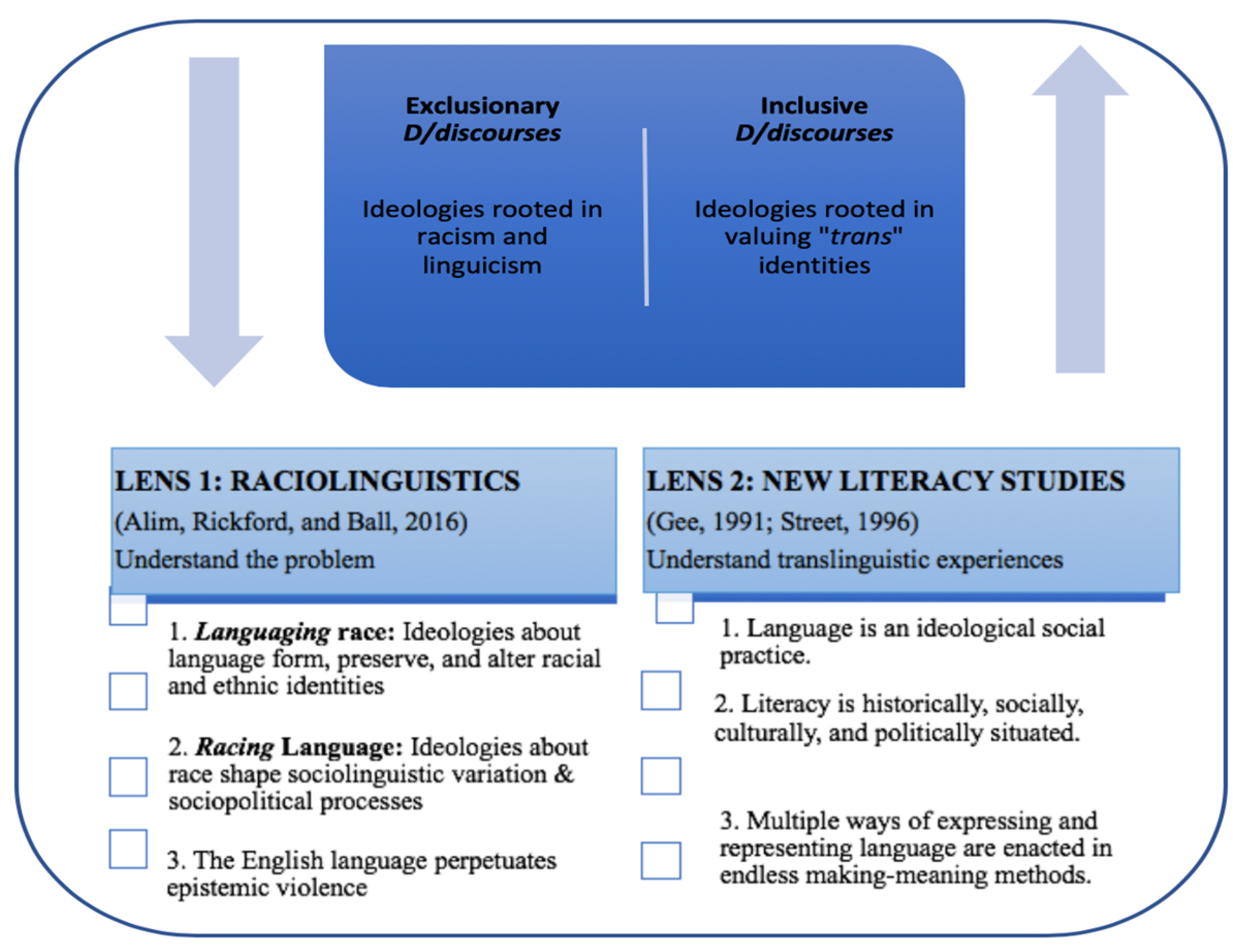

1.1. Framing Translingual Experiences with New Literacy Studies and Raciolinguistics

1.2. The Prefix “Trans” and Translingualism

1.3. Epistemic Racism against Translinguals

1.4. Translingual Epistemologies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Violence

1.5. Study Purpose and Significance

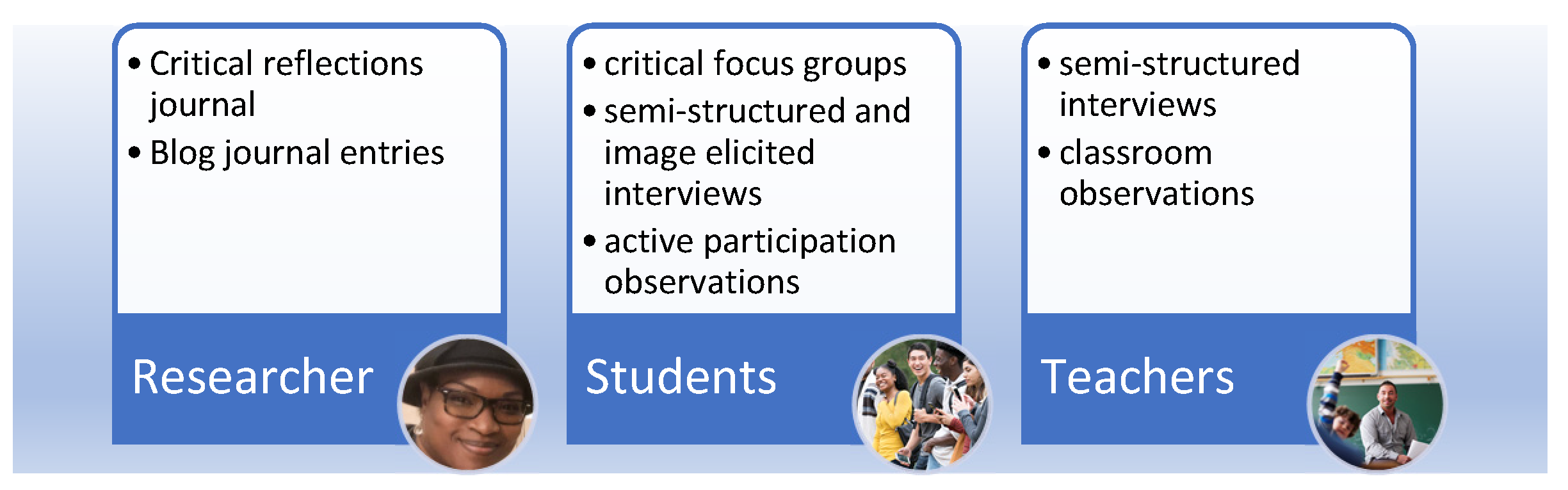

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Research Subject/Participant

2.3.2. Student Data Collection

- Four critical focus group discussions:

- Semi-structured interviews:

- Image-elicited interviews:

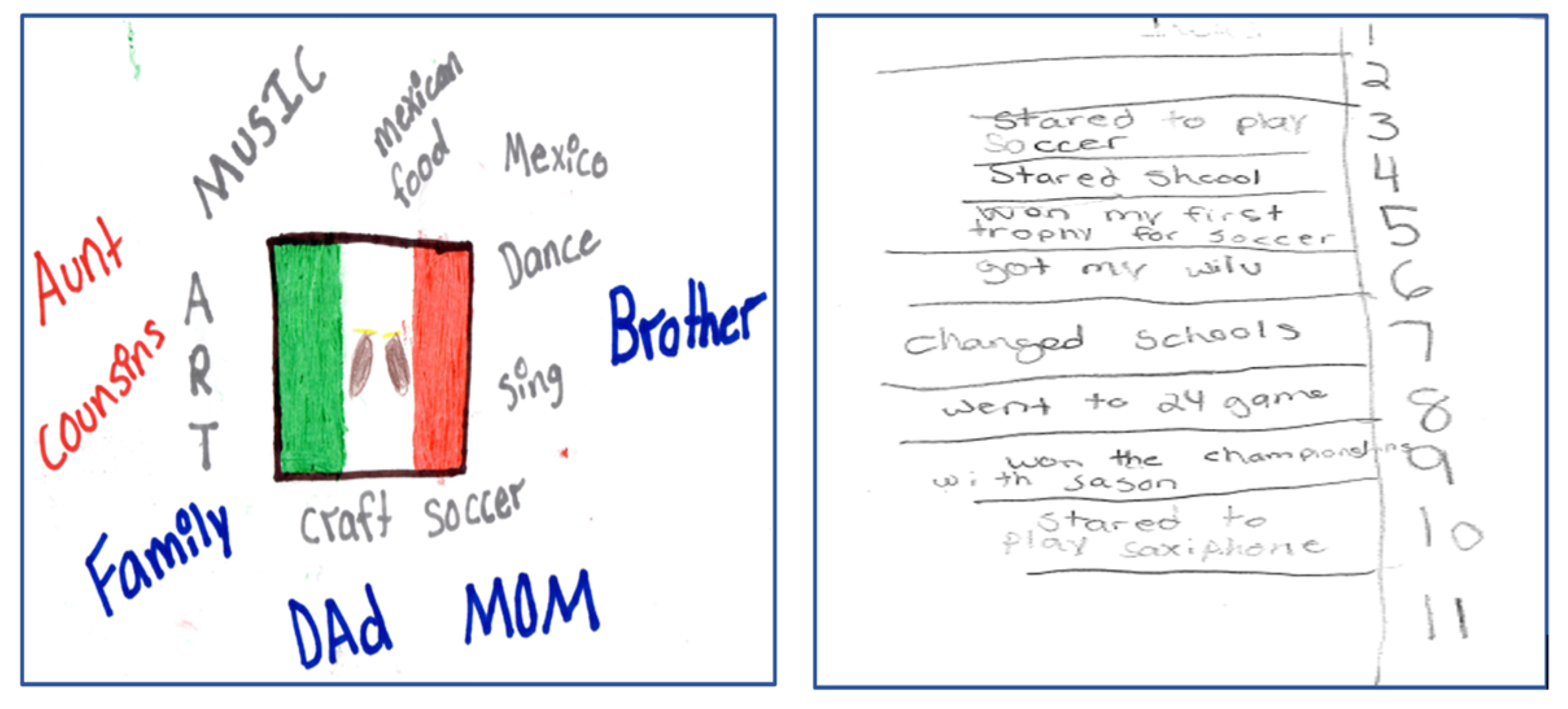

- Self-portraits:

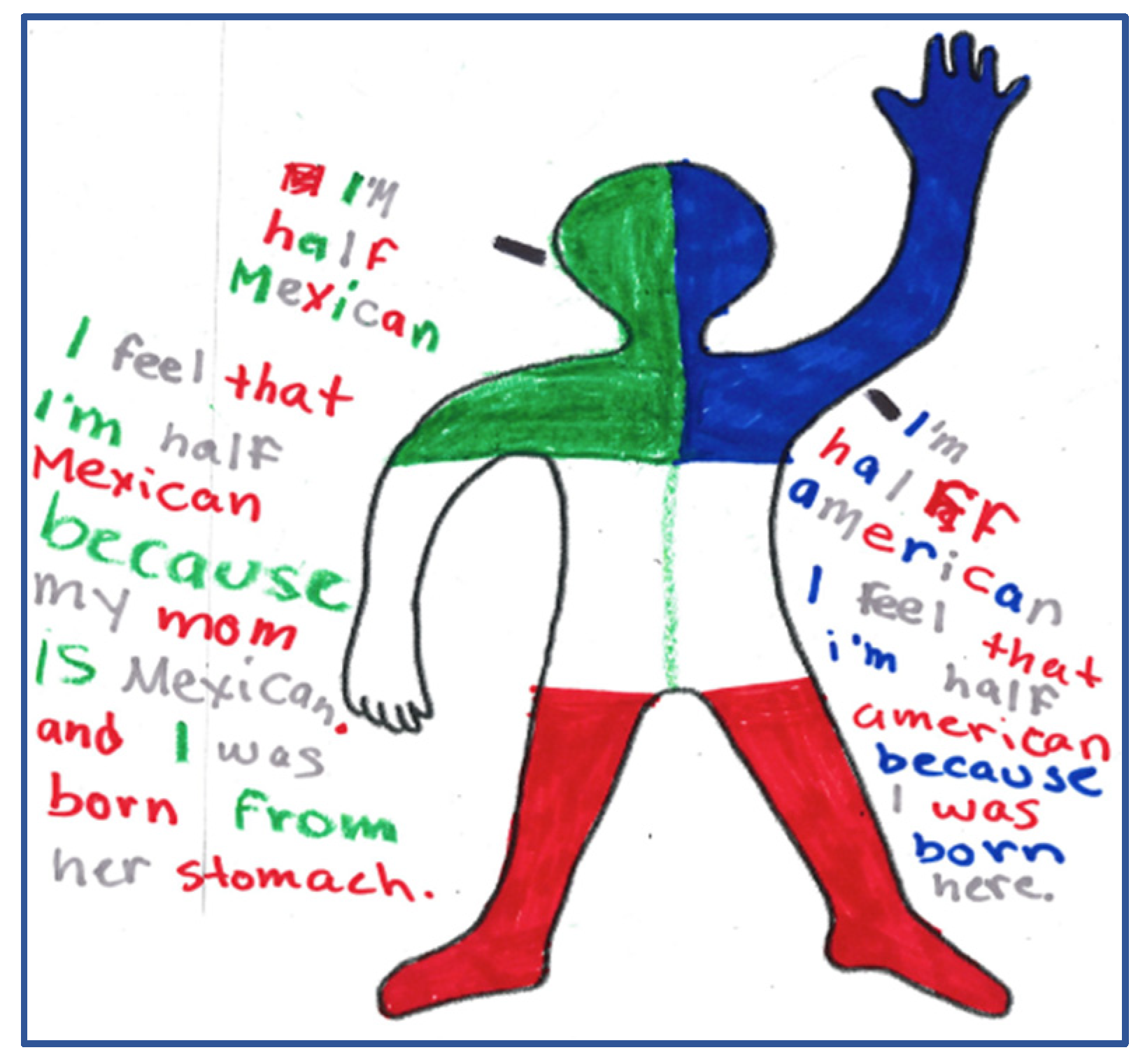

- Language silhouettes:

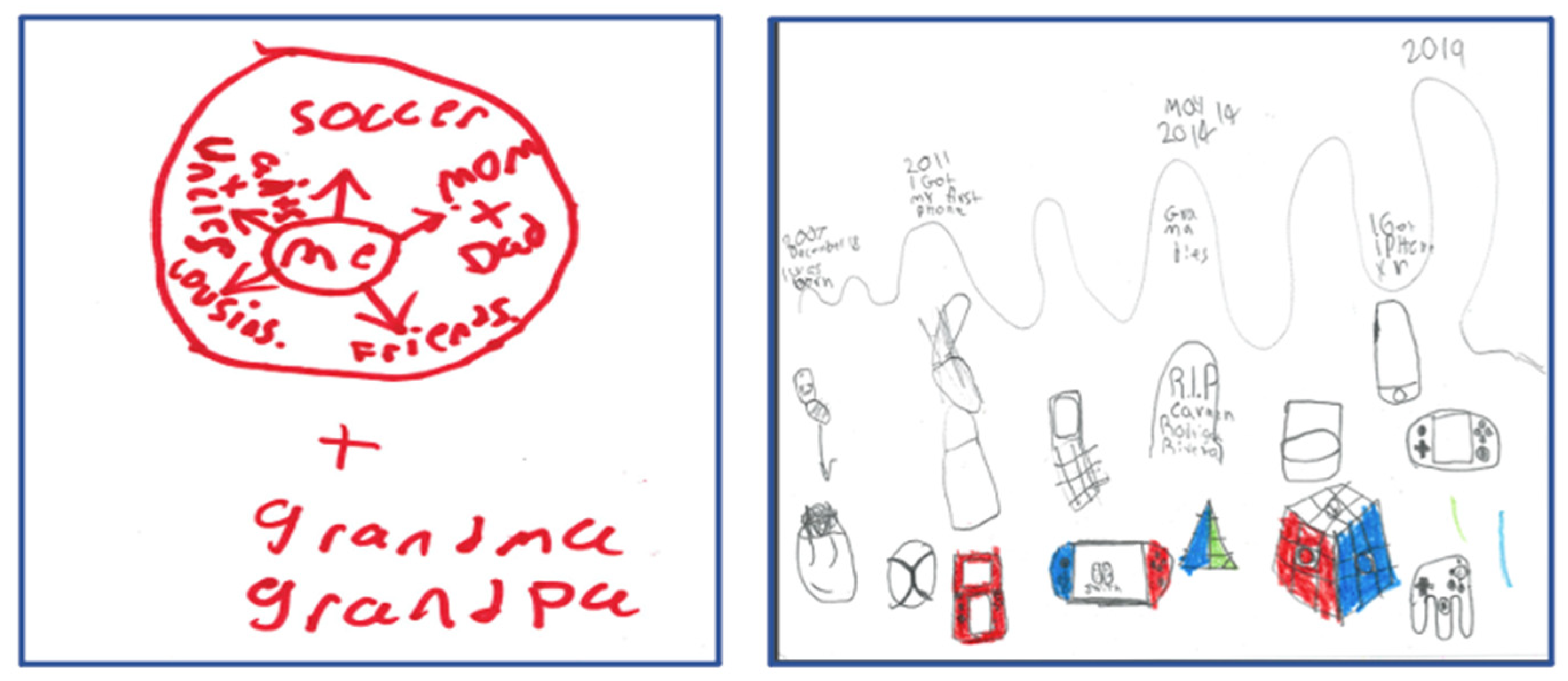

- Relational maps:

- Timelines:

- Emplaced sensory observations:

2.3.3. Teacher Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

The situated meaning tool–“tells us what words and phrases mean in a specific context…watch for cases where words and phrases are being given situated meanings that are nuanced and quite specific to the speaker’s worldview or values” [80] (p. 160).

The Figured World Tool–“models or pictures that people hold about how things work in the world when they are ‘typical’ or ‘normal’…can become means to judge and discriminate against people who are taken as untypical or not normal” [80] (p. 178).

The Bid D Discourse tool–“People do talk and act just as individuals, but as members of various social and cultural groups [80] (p. 186) that represent various Discourses, or ‘identity kits’ [7] that symbolize how people act, interrelate, believe, assign worth, think, and communicate. They are the materialization of specific roles or types of people [80].

3. Results

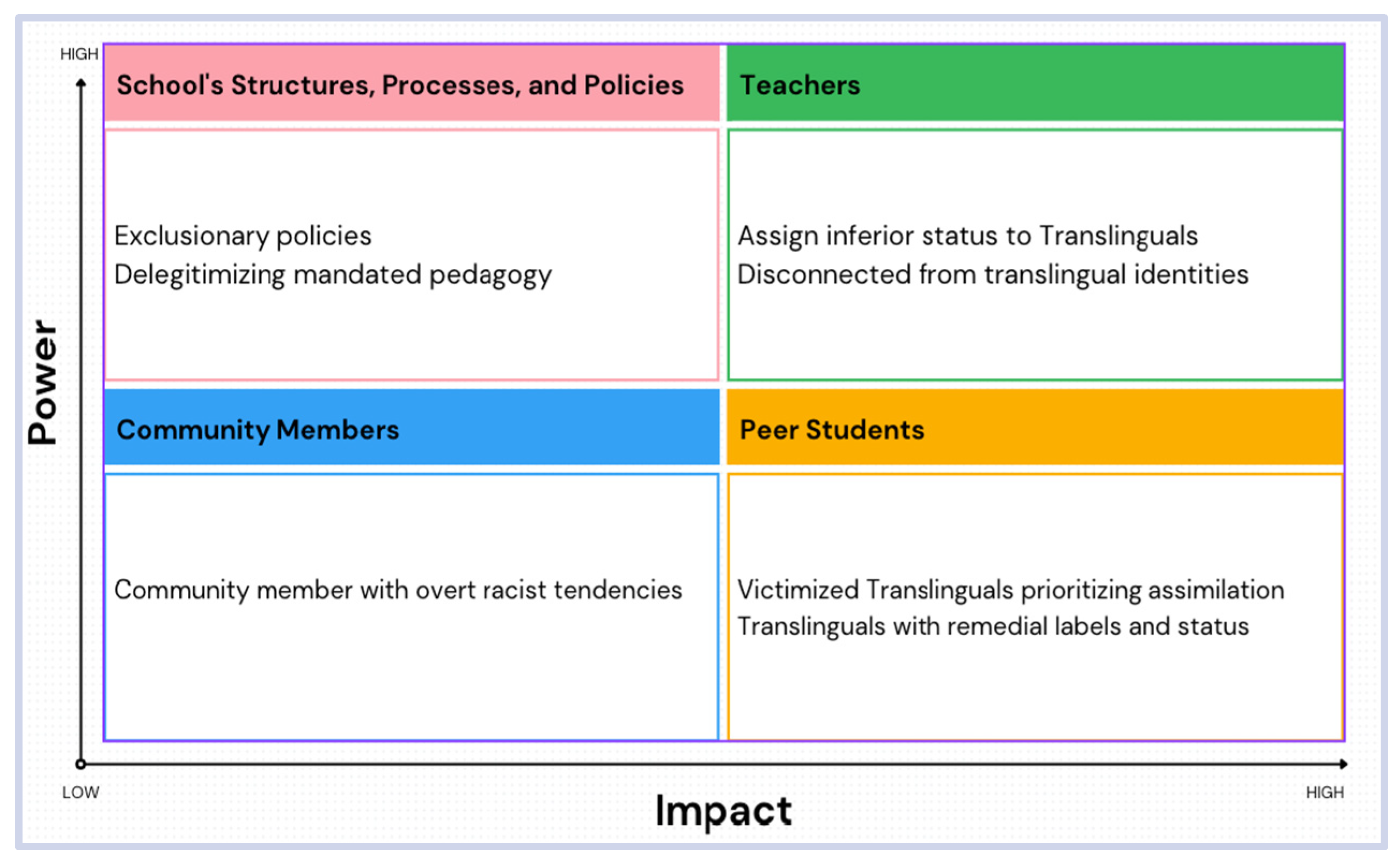

3.1. Characteristics of Agents of Epistemic Racism

3.1.1. Individualities of Agents of Epistemic Racism

3.1.2. Ideological Enactment of Agents of Epistemic Racism

3.2. Transresistance: How Translinguals Reject and Combat Epistemic Racism

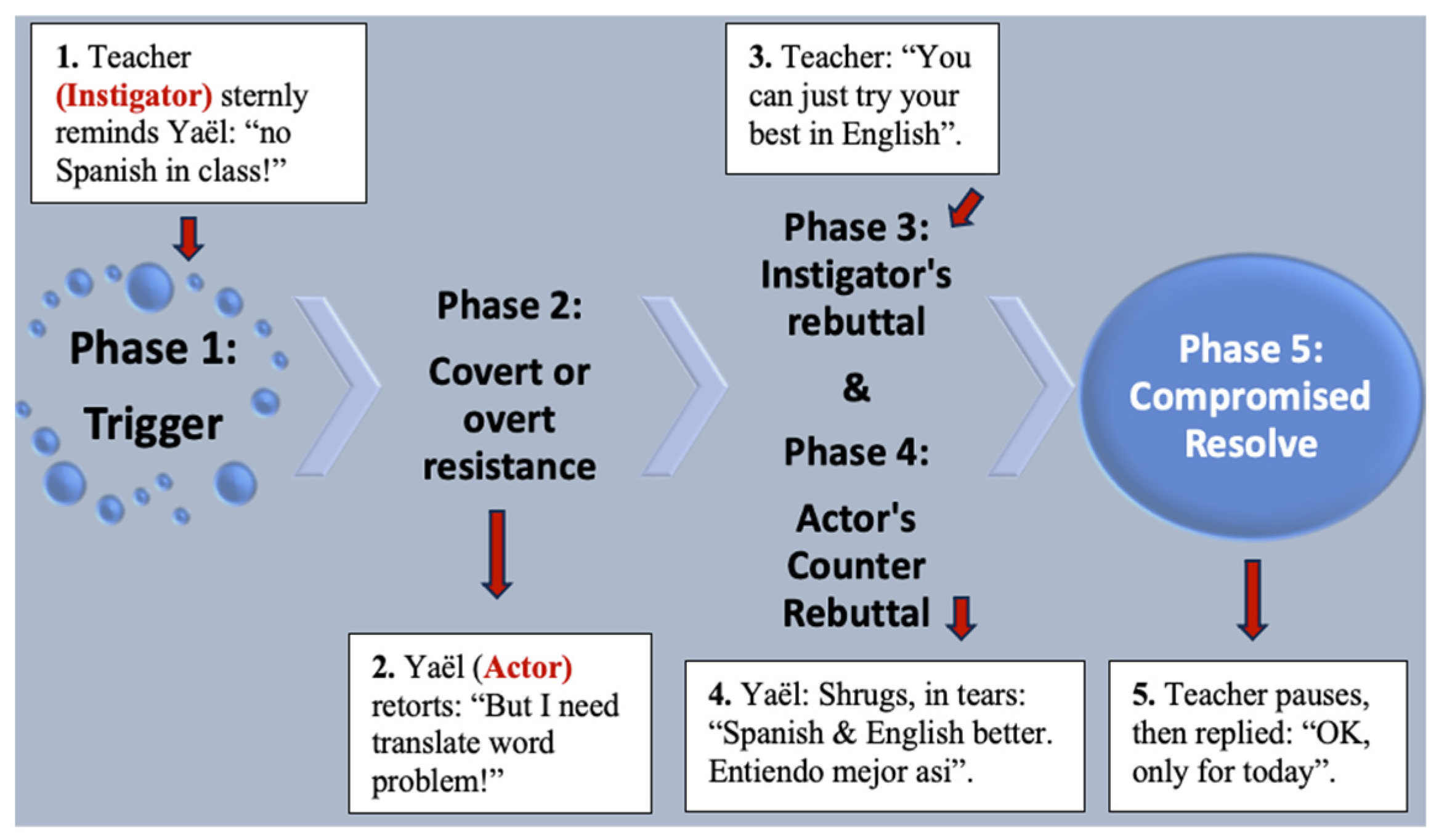

3.2.1. Covert and Overt Transresistance

3.2.2. Transresistance: Combatting Epistemic Racism with Transliteracies

4. Discussion

4.1. Epistemic Racism Agents and Bad Discourses

4.2. Transresistance: Types, Components, and Phases When in Motion

4.3. Implications

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chrona, J. Epistemic Racism, Indigenous Knowledges, and Curriculum. 12 February 2022. Available online: https://luudisk.com/2022/02/12/epistemic-racism-indigenous-knowledges-and-curriculum/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Swan, C. Challenging epistemic racism: Incorporating Māori knowledge into the Aotearoa New Zealand education system. J. Initial. Teach. Inq. 2018, 4, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 39, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. Multilingualism and language education. In The Routledge Companion to English Studies; Leung, C., Street, B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, M. Transcultural and Translinguistic Latinx Discourses: Challenging Raciolinguistic Discourses in a School Community—Towards a Frame of Resistance. Ph.D. Thesis, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.K. Raciolinguistic ideology of antiblackness: Bilingual education, tracking, and the multiracial imaginary in urban schools. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2018, 31, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P. Discourse analysis, what makes it critical. In Critical Discourse Analysis in Education; Rogers, R., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005; pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, G.A.; Schultz, K. (Eds.) School’s out: Bridging out-of-School Literacies with Classroom Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Janks, H. Domination, access, diversity and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educ. Rev. 2000, 52, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H.S.; Rickford, J.R.; Ball, R.A. Introducing Raciolinguistics: Racing language and languaging race in hyperracial times. In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race; Alim, H.S., Rickford, J.R., Ball, A.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, N.; Rosa, J. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2015, 85, 149–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, A.M. New Blacks: Language, DNA, and the construction of the African American/Dominican boundary of difference. Genealogy 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, N.; Phuong, J.; Venegas, K.M. “Technically an EL”: The production of Raciolinguistic categories in a dual language school. TESOL Q. 2020, 54, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanišić, S. Three Myths of Immigrant Writing: A View from Germany. Words without Borders. 2008. Available online: https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2008-11/three-myths-of-immigrant-writing-a-view-from-germany/ (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Canagarajah, A.S. Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Canagarajah, S. Translingualism and world Englishes. Bloomsbury World Englishes Paradig. 2021, 1, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Street, B. What’s “new” in New Literacy Studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2003, 5, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. Translanguaging as a political stance: Implications for English language education. ELT J. 2022, 76, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.S.B. Transdisciplinary Approaches to Language Learning and Teaching in Transnational Times. L2 J. 2016, 8, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Ho, W.Y.J. Language learning sans frontiers: A translanguaging view. Ann. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 38, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R. Confronting epistemological racism, decolonizing scholarly knowledge: Race and gender in applied linguistics. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 41, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, Z.; Young, M.; Balmer, D.F.; Park, Y.S. Endarkening the epistemé: Critical Race Theory and medical education scholarship. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, Si–Sv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, L.R. Existentia Africana: Understanding Africana Existential Thought; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2000; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, G. Kaupapa Māori research: Epistemic wilderness as freedom? N. Zeal. J. Educ. Stud. 2012, 47, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, H.; Rubie-Davies, C.M.; Webber, M. Teacher expectations, ethnicity and the achievement gap. N. Zeal. J. Educ. Stud. 2015, 50, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, Z.; Grubb, W. Education and Racism: A Primer on Issues and Dilemmas, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Noroozi, N. Counteracting Epistemic Totality and Weakening Mental Rigidities: The Antitotalitarian Nature of Wonderment. 2015, pp. 273–283. Available online: https://ojs.education.illinois.edu/index.php/pes/article/view/4500 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Lippi-Green, R. English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P. Rethinking the role of “culture” in educational equity: From cultural competence to equity literacy. Multicult. Perspect. 2016, 18, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A. Voice, footing, enregisterment. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 2005, 15, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, D.; Dendrinos, B.; Gounari, P. Hegemony of English; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.; Young, S. Troubling tolichism in several voices: Resisting epistemic violence in creative analytical and critical autoethnographic practice. J. Autoethnography 2022, 3, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, C. Conceptualizing epistemic violence: An interdisciplinary assemblage for IR. Int. Polit. Rev. 2021, 9, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Moreno, L.C. Racist and Raciolinguistic teacher ideologies: When bilingual education is “inherently culturally relevant” for Latinxs. Urban Rev. 2022, 54, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, R.; Kress, G. Language as Ideology, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Santos, B. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phyak, P. Epistemicide, deficit language ideology, and (de)coloniality in language education policy. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2021, 2021, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, K. Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia 2011, 26, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W.D. Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory Cult. Soc. 2009, 26, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, C. Home Pages: Literacy Links for Bilingual Children; Trentham Press: Stroke on Tent, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kenner, C. Becoming Biliterate; Trentham Press: Stroke on Tent, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, W.; Vasquez, R.; Buriel, A.R. Zapotec, Mixtec, and Purepecha youth. In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race; Alim, H.S., Rickford, J.R., Ball, A.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsu, L.; Zacharias, S.; Futro, D. Translingual arts-based practices for language learners. ELT J. 2021, 75, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth Gordon, J. From upstanding citizen to North American rapper and Black again. In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race; Alim, H.S., Rickford, J.R., Ball, A.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Malsbary, C. “Will this hell never end?”: Substantiating and resisting race-language policies in a multilingual high school. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2014, 45, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C. Lived experiences, funds of identity and education. Cult. Psychol. 2014, 20, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, A. “I want to be a furious leopard with magical wings and super power”: Developing an ethico-interpretive framework for detecting Chinese students’ funds of identity. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1316915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R. A Critical Discourse Analysis of Family Literacy Practices: Power in and out of Print; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. Case studies. In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 134–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hinic, K.; Kowalski, M.O.; Silverstein, W. Professor in residence: An innovative academic-practice partnership. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2017, 48, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Purposeful Sampling. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, S.B. Ethnography in education: Defining the essentials. In Children in and out of School, Ethnography and Education; Perry, G., Allan, A.G., Eds.; Center for Applied Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, F. What Makes School Ethnography ‘Ethnographic’? Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1984, 15, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 2021, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicks, B. Action, experience, communication: Three methodological paradigms for researching multimodal and multisensory settings. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Doing Sensory Ethnography; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderud, J.R. Playing, Sensing, and Meaning: An Ethnographic Study of Children’s Self-Governed Play in a Norwegian Nature Kindergarten. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, R. Critical Trans-literacies in a teacher’s transformation course: Media, textbooks and processes of decolonialities. Calidoscópio 2021, 19, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Kevern, J. Focus Groups as a Research Method: A Critique of Some Aspects of Their Use in Nursing Research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, V. Focus groups: A useful method for educational research? Br. Educ. Res. J. 1997, 23, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, I.; Stevens, B.; McKeever, P.; Baruchel, S. Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children’s perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkeland, Å.; Grindheim, L.T. Photo-Elicitation Interviews—A Possibility for Collaborative Provocation of Preconceptions: Visuality Design in and for Education. Video J. Educ. Pedagog. 2022, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, R. Exploring linguistic identity in young multilingual learners. TESL Can. J. 2014, 32, 42–552. [Google Scholar]

- Pivac, D.; Zemunik, M. The self-portrait as a means of self-investigation, self-projection and identification among the primary school population in Croatia. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2020, 10, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaja, P.; Pitkänen-Huhta, A. ALR special issue: Visual methods in applied language studies. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2018, 9, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. Discovering pupils’ linguistic repertoires. On the way towards a heteroglossic foreign language teaching. Sprogforum 2014, 59, 87–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, A.M.J.; De Meulder, M. Language portraits: Investigating embodied multilingual and multimodal repertoires. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Inst.Klin. Sychologie Gemeindesychologie 2019, 20, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B. Coloured language: Identity perception of children in bilingual programmes. Lang. Aware. 2012, 21, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looman, W.S.; Eull, D.J.; Bell, A.N.; Gallagher, T.T.; Nersesian, P.V. Participant-generated timelines as a novel strategy for assessing youth resilience factors: A mixed-methods, community-based study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 67, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nugent, C.L. Sensory-ethnographic observations at three nature kindergartens. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2018, 41, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Doing Sensory Ethnography; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ. Commun. Technol. J. 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincon, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. How to Do Discourse Analysis: A Toolkit; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Language and Symbolic Power (G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.); Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, R.; Hristova, S. Slogans of White Supremacy: Imagined Minority Corruption in Trump-Era Politics. In Corruption and Illiberal Politics in the Trump Era; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski, M.; Bauldry, S. The effects of perceived discrimination on immigrant and refugee physical and mental health. In Immigration and Health; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.E.D.T.; Pebley, A.R. Legal status, time in the USA, and the well-being of Latinos in Los Angeles. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, R.; Kumagai, Y. Translingual practices in a ‘Monolingual’ society: Discourses, learners’ subjectivities and language choices. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, M.; Hall, K. Language and identity. In The Companion to Linguistic Anthropology; Duranti, A., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett, M.; Wong, G.; Haglund, N.; Issawi, S. The Digital Cahier Collective: Fostering Québec-Michigan Cultural Exchange Through Co-Curricular Multimodal Composition Practices. J. Glob. Literacies Technol. Emerg. Pedagog. 2022, 8, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzell, D.; Flores Carmona, J. Testimonios as a Methodological Third Space: Disrupting Epistemological Racism in Applied Linguistics. J. Lat. Educ. 2023, 68, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, S.L.; Langhout, R.D.; Rusch, D.; Mehta, T.; Rubén Chávez, N.; Ferreira van Leer, K.; Oberoi, A.; Indart, M.; Paloma, V.; King, V.E.; et al. The Roles of Settings in Supporting Immigrants’ Resistance to Injustice and Oppression: A Policy Position Statement by the Society for Community Research and Action—A Policy Statement by the Society for Community Research and Action: Division 27 of the American Psychological Association. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T.; Phillipson, R.; Kontra, M. Reflection on Scholarship and Linguistic Rights: A Rejoinder to Jan Blommaert. J. Socioling. 2022, 5, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.H. The Everyday Language of White Racism; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, A.; Makoni, S. Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2007; pp. i–xix. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, M.; Sa’ke’J, H. Indigenous and Trans-Systemic Knowledge Systems (ᐃᐣdᐃgᐁᓅᐢ ᐠᓄᐤᐪᐁdgᐁ ᐊᐣd ᐟᕒᐊᐣᐢᐢᐩᐢᑌᒥᐨ ᐠᓄᐤᐪᐁdgᐁ ᐢᐩᐢᑌᒼᐢ). Engaged Sch. J. 2021, 1, i–xix. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, W.Y. Toward an anti-Raciolinguistic anthropology: An Indigenous response to White supremacy. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 2021, 3, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, C.; Gonzales, L. Unpacking language weaponization in Spanish(es): Supporting transnational antiracist relationality. Int. J. Lit. Cult. Lang. Educ. 2022, 2, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. Critical Language Awareness and Student Vulnerability: The Case for Contextual Rhetorical Propriety. Double Helix 2022, 10, 395–396. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. Writing Toward a Decolonial Option: A Bilingual Student’s Multimodal Composing as a Site of Translingual Activism and Justice. Writ. Commun. 2023, 40, 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, M.; Tian, K. Critical Information Literacy Education Strategies for University Students in the Post-Pandemic Era. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2022, 6, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Student Names | Age | Place of Birth | Response to: What Is Your Nationality? | Response to: What Is (Are) Your Mother’s Tongue(s)? | Response to: What Language(s) Do You Most Use At Home/ At School? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natalia | 10 | United States | I don’t know (shrugging) | Spanish | Both |

| Magdalena | 10 | United States | I don’t know | English for my dad and then Spanish for my mom | English/Spanish because of my mom |

| Joalene | 10 | United States | I was born in New York, so I am American, but I am also Mexican | English | Spanish with parents, English with brother |

| Dina | 11 | United States | Mexican-American | English | English |

| Yaël | 11 | Puerto Rico | Boricua, like Caribbean because I was born in Puerto Rico | Spanish, I only speak a lot of English at school | Spanish |

| Julio | 11 | United States | Mexican | Mexican Spanish and English too | Spanish and English, but English more |

| Javier | 11 | United States | I am Mexican and half American because I was born here | Mostly English ‘cause of school and Spanish at home ‘cause it’s easier for my parents to speak Spanish | Both |

| Research Questions | Themes That Address Questions |

|---|---|

| RQ1. What are the characteristics of delegitimizing school stakeholders who become agents of epistemic racism in their interactions with translingual students? | Theme 1. Agents of Epistemic Racism: Individualities and Ideological Enactment of Epistemic Racism |

| Theme 1.a. Individualities of Agents of Epistemic Racism Theme 1.b. Ideological Enactment of Epistemic Racism | |

| RQ2. How do translingual students reject these agents’ marginalization? | Theme 2. Transresistance–Using a System of Transliteracies to Combat Epistemic Racism |

| Theme 2.a. Combatting Epistemic Racism with Covert Transresistance and Overt Transresistance Theme 2.b. Transresistance–Resistance Transliteracies |

| Transresistance in Action | Example | Covert or Overt |

|---|---|---|

| Proclaiming the validity of their mother tongue | Speaking Spanish in classrooms where the teacher sternly forbids it. | Overt |

| Subtly proclaiming pride in translingual identity | Showing off globalized and multilingual identity in writing exercises by using mother tongue and newly learned language (Korean learned from K Pop Music). | Covert |

| Expressing dual allegiance and complex identity relative to American and Mexican cultures | Telling teacher and classmates that they are both American and Mexican, sharing examples of belonging to both ways of being in class oral report, and voicing that they think it means you are cool and smart. | Overt |

| Opposing agents of epistemic racism | Translingual direct challenges to teachers and other adults when they feel they have been marginalized because of racism and linguicism. | Overt |

| Denouncing Raciolinguistic ideologies to ally peers and adults in the school community | Participants using immigrant-friendly political narratives in discussions about politics and current societal issues. | Covert (in safe places only) or overt in public |

| Affiliating with other minoritized groups in social contexts to avoid enduring marginalization alone | Groups of participants often sitting with Black and other Latinx students with whom they share similarities and using them as a safety net. | Covert |

| Going along with racist and linguistic oppressive actions and speech when in public | Using attitudes and nonverbal expression to show disapproval of epistemic racism. | Covert |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fall, M.S.B. Introducing “Trans~Resistance”: Translingual Literacies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Raciolinguistic Discourses in Schools. Societies 2023, 13, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080190

Fall MSB. Introducing “Trans~Resistance”: Translingual Literacies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Raciolinguistic Discourses in Schools. Societies. 2023; 13(8):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080190

Chicago/Turabian StyleFall, Madjiguene Salma Bah. 2023. "Introducing “Trans~Resistance”: Translingual Literacies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Raciolinguistic Discourses in Schools" Societies 13, no. 8: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080190

APA StyleFall, M. S. B. (2023). Introducing “Trans~Resistance”: Translingual Literacies as Resistance to Epistemic Racism and Raciolinguistic Discourses in Schools. Societies, 13(8), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080190