The Populist Divide in Far-Right Political Discourse in Sweden: Anti-Immigration Claims in the Swedish Socially Conservative Online Newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim and Contributions

3. Background

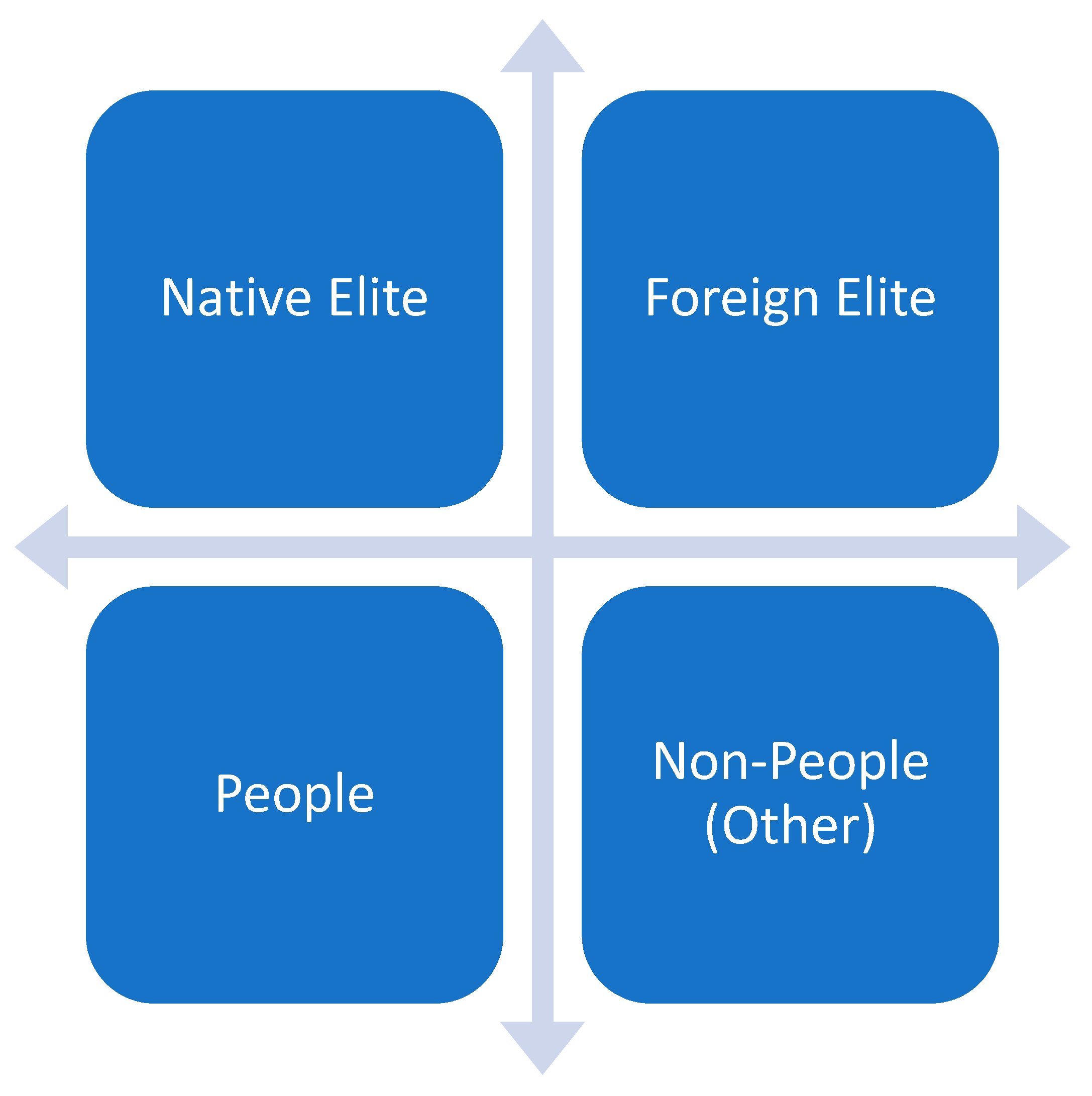

4. Theory

5. The Populist Divide

5.1. Anti-Elitism

5.2. People-Centrism

6. Method

7. Material

8. Analysis

8.1. Anti-Elitism

8.1.1. Political Elite

[T]he national community is necessary for a welfare state that can provide basic security, especially for those who do not have their own resources as backup. Without nationalism, no tax revenue to the state. Without nationalism, no democracy where everyone has an equal voice.

8.1.2. Cultural Elite

In Sweden, we see the same arrogant denial of natural restrictions in the migration policy pursued for decades. The ruling parties (from M to V)7 have deliberately allowed hundreds of thousands of people from foreign civilisations to come to Sweden—without having a plan for housing, schools, healthcare, social care, or a police force that can handle people from significantly more violent cultures.

8.1.3. Moral Elite

8.1.4. Media Elite

8.1.5. EU Elite

8.1.6. Economic Elite

8.2. People-Centrism

8.2.1. The United People

The national process of dissolution that had resulted from the left-liberal immigration and refugee policy, which was also the explicit intention when the decision was made in the Riksdag in 1975 to transform Sweden into “a multilingual and multicultural society”, must be reconsidered. The previously culturally rooted national unity in Sweden is destroyed, which has already had very severe consequences.[62]

Other parties (but the SD, my emphasis) advocate multiculturalism, in reality, an effective way to tear society apart if the experiment is pushed too far. Unfortunately, community and trust risk eroding even within the people in the majority society.

The parties that neglect this issue deny the importance of culture, language, values and national identity/.../It is not that those who arrive in Sweden dump their values from their home country at the Swedish border. The many problems we have in Sweden today, such as honour oppression, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, segregation, parallel societies, etc., show that many immigrants bring their values to Sweden, which affects society.

Only if the West regains its national feeling and again shows that it is proud of what our civilisation has created—and in fact: almost everything that humanity today benefits from was discovered, developed, and created in the West—can we meet the challenges of the destructive forces of totalitarian countries.

8.2.2. Our People

Humility is a virtue. Team spirit and collective endeavour have served our small nation well. We do not exalt ourselves in self-sufficiency. We try to agree and reach a consensus before confrontation and conflict.[66]

On 1 May, traditional messages from the labour movement are brought to life. But they have no bearing on current politics, where they instead raise identity politics, “racialisation”, and radical feminism instead of defending the working people’s conditions. In Sweden, Per Albin Hansson built the people’s home, a conservative political idea that was merged with social-political reformism. Social democracy abandoned the class struggle for consensus, and abandoned internationalism for a national perspective.[67]

8.2.3. The Common People

This society may “function” in its own way, but it is clearly something different from what most people had imagined or hoped for ten years ago, with female genital mutilation, honour suppression, self-appointed moral police, and an abysmal misunderstanding between large social groups. Moreover, in many places, increasing rates of serious crime.

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | What Ignazi labelled as the “silent counter-revolution”, which he associated with the rise of Jean-Marie Le Pen and la nouvelle droite (the new right) in France in the early 1970s. Bale and Kaltwasser provide further elaboration on the silent counter-revolution and the various manifestations of both reactions and counter-reactions to this in different countries [4]. |

| 2 | The advent of the fourth wave follows from the eruption of three crises from which the far-right parties, electorally, have profited [3] (p. 20). These are, according to Mudde, the terrorist attacks of September 2001, the Great Recession of 2008, and the reception refugee crisis of 2015. |

| 3 | Similar studies have shown a similar development in Romania and Hungary, where appeals of national identity merge with chauvinistic welfare appeals [8]. (See in particular chapter 4 by Radu Cinpoes and Ov Cristian Norocel in this book). |

| 4 | See further Brubaker and Cooper [30] for an elaboration of this distinction in relation to the concept of “identity” in social science. |

| 5 | For a critical discussion on so-called populist ideational attitudes in populist communication, see further [33]. |

| 6 | The views on national identity are not strictly limited to editorials or chronicles, but can also appear in other sections as well, as for instance in the genre of news articles (see the analysis). All the quotes in the analysis have been translated from Swedish to English by the author. |

| 7 | M stand for Moderaterna (the governing mainstream right party), while V (Vänsterpartiet) stands for the left party. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | This is interesting in its own right; however, I refrain from drawing too strong of a conclusion based on this rather limited sample and can thus reveal more about the selection of articles; thus, it does not necessarily correspond to the totality of voices in the far-right political environment during the selected time frame. |

| 10 | One such key figure in Swedish history writing is Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson, a nobleman and miner in the province of Dalarna who mobilised peasants and mineworkers in his home area, which spread throughout the country. The rebellion has been seen as a Swedish awakening, a symbol of claims for national sovereignty [10] (p. 63). |

| 11 | People´s Home has, historically, been used by the Social Democratic Party to realizing and administrating social reforms, what we today associate with the building of the universal welfare state [73]. |

References

- SCB 2022 Utrikes Födda i Sverige. Available online: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda-i-sverige/#:~:text=De%20senaste%20%C3%A5ren%20har%20m%C3%A5nga,%C3%A4r%2020%20procent%20av%20befolkningen (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Ruzza, C. Populism and Euroscepticism: Towards uncivil society? Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. The Far Right Today; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, T.; Rovira-Kaltwasser, C. Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. The boundaries of what can be said have shifted’: An expert interview with Ruth Wodak (questions posed by Andreas Schulz). Discourse Soc. 2019, 31, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, B. Populism; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bevelander, P.; Wodak, R. (Eds.) Europe at the Crossroads: Confronting Populist, Nationalist and Global Challenges; Nordic Academic Press: Lund, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Norocel, O.C.; Hellström, A.; Bak-Jørgensen, M. Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A. Trust Us: Reproducing the Nation and the Scandinavian Nationalist Populist Parties; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Demker, M. Sverige åt Svenskarna: Motstånd och Mobilisering mot Invandring och Invandrare i Sverige [Sweden for the Swedes: Resistance and Mobilization against Immigration and Immigrants in Sweden]; Atlas: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Emilsson, H. Continuity or Change? The Impact of the Refugee Crisis on Swedish Political Parties’ Migration Policy Preferences, In Forced Migration and Resilience; Fingerle, M., Wink, R., Eds.; Studien zur Resilienzforschung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bevelander, P.; Hellström, A. Pro- and Anti-Migrant Mobilizations in Polarized Sweden. In The Refugee Reception Crisis in Europe; Rea, A., Martinello, M., Mazzola, A., Meuleman, B., Eds.; Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2019; pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rydgren, J.; van Meiden, S. Sweden, Now a Country Like All the Others? The Radical Right and the End of Swedish Exceptionalism; Working Paper Series No. 25; University of Stockholm, Department of Sociology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kitschelt, H.; Mcgann, A. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbour, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy. West Eur. Politics 2010, 33, 1167–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, E. Nordic Nationalism and Right-Wing Populist Politics: Imperial Relationships and National Sentiments; Palgrave Macmillian: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Bevelander, P. When the media matters for electoral performance. Sociol. Forsk. 2018, 55, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. The Populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 2004, 39, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydgren, J. (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A. The Losers Are Winning Thanks to the Sweden Democrats, ECPS Commentary. Available online: https://www.populismstudies.org/the-losers-are-winning-in-sweden-thanks-to-the-sweden-democrats/?fbclid=IwAR1nXr2fMt2qTO7g9tw0LHEZBEu_6Fah2Tq4_Tn-m906DWEUS6kpXstMlVY (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Hampshire, J. The Politics of Immigration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżanowski, M. Discursive shifts and the normalisation of racism: Imaginaries of immigration, moral panics and the discourse of contemporary right-wing populism. Soc. Semiot. 2020, 30, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.-W. What Is Populism? University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oudenampsen, M. Political Populism: Speaking to the Imagination. In The Populist Imagination: On the Role of Myth, Storytelling and Imaginary in Politics; Seijdel, J., Ed.; Nai: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Canovan, M. Populism for political theorists? J. Political Ideol. 2004, 9, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P. “Bryan, Bryan, Bryan, Bryan”: Democratic Theory, Populism, and Philip Roth’s “American Trilogy”. Can. Rev. Am. Stud. 2007, 37, 431–452. [Google Scholar]

- Canovan, M. Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy. Political Stud. 1999, 47, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, F. Populism and the Mirror of Democracy {XE “Democracy”}. In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy {XE “Democracy”}; Panizza, F., Ed.; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, R.; Cooper, F. Beyond Identity. Theory Soc. 2000, 29, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, T. Populism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, R. Populism and Nationalism. Nations Natl. 2019, 26, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefford, G.; Moffitt, B.; Werner, A. Populist Attitudes: Bringing Together Ideational and Communicative Approaches. Political Stud. 2021, 70, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cleen, B.; Stavrakakis, Y. Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javn. Public 2017, 24, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A. Populism and Nationalism: An Overview of similarities and differences. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2021, 56, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C. Tänka Fritt Teller Tänka på Andra: Om Politisk Korrekthet, Yttrandefrihet Och Tolerans; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Canovan, M. Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy. In Democracies and the Populist Challenge; Meny, Y., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Gordonsville, TN, USA, 2002; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bottici, C. A Philosophy of Political Myth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elgenius, G. Symbols of Nations and Nationalism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, T. Progressive answers to populism in Hungary. In Progressive Answers to Populism. Why Europeans Vote for Populist Parties and How Progressives Should Respond to This Challenge; Stetter, F., Boros, T., Freitas, M., Eds.; FEPS—Foundation for European Progressive Studies/Budapest: Policy Solutions: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. The ‘Golden Age’ and National Renewal. In Myths & Nationhood; Hosking, G., Schöpflin, G., Eds.; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 30–59. [Google Scholar]

- Taggart, P. Populism; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Norocel, O.C.N.; Pettersson, K. Imbrications of gender and religion in Nordic radical right populism. Identities 2022, 29, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norocel, O.C. Åkesson at Almedalen: Intersectional Tensions and Normalisation of Populist Radical Right Discourse in Sweden. NORA Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2017, 25, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.R.; Gibson, G.D. Reclaiming the Epistemological ‘Other’: Narrative and the Social Constitution of Identity. In Social Theory and the Politics of Identity; Calhoun, C., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 37–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Edenborg, E. Politics of Shame: Life Stories of the Sweden Democrats´ voters in a counter public sphere. In L’extrême droite en Europe; Jamin, J., Ed.; Bruylant: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015; pp. 457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Norocel, O.C.; Jørgensen, M.B. Nostalgia and Hope: Narrative Master Frames across Contemporary Europe. In Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe; Norocel, O.C., Hellström, A., Jørgensen, M.B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck, J.; Andersson, F.; Nedlund, E. Invandring i Medierna: Hur Rapporterade Svenska Tidningar 2005–2015? The Migration Studies Delegation (DELMI), Report; Delmi: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Expo 20221222 ‘Samtiden’. Available online: https://expo.se/fakta/wiki/samtiden (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Hellström, A.; Nilsson, T. We are the Good Guys: Ideological positioning of the nationalist party {XE “party”} Sverigedemokraterna in contemporary Swedish politics. Ethnicities 2010, 10, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erixon, D. Moderaternas Vägval: Lär av Bohman! Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2018/11/moderaternas-vagval-lar-av-bohman/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Kartlagt: Saknaden Efter Ett Tryggt Samhälle Som Känns Som Hemma. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2022/08/kartlagt-saknaden-efter-ett-tryggt-samhalle-som-kanns-som-hemma/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Coronakommissionen: Den Svenska Hanteringen Var Ett Haveri. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2021/10/coronakommissionen-den-svenska-hanteringen-var-ett-haveri/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. De Progressivas Världsbild är en Revolt mot Verklighten. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2019/07/de-progressivas-varldsbild-ar-en-revolt-mot-verkligheten/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Ignazi, P. The silent counter-revolution: Hypotheses on the emergence of extreme right-wing parties in Europe. Eur. J. Political Res. 1992, 39, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinas, A.E. The Media and the Far Right in Western Europe {XE “Europe”}: Playing the Nationalist Card; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- We Anderson, J. Aktivismen Som Sporrar Hat Och Motsättningar. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2018/11/aktivismen-som-sporrar-hat-och-motsattningar/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. ’Identitetspolitiken i V Kontra Gemenskap i SD. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2020/02/identitetspolitiken-i-v-kontra-gemenskap-i-sd/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Gholam Ali Pour, N. Vem Ska Integreras om Etniska Svenskar Blir en Minoritet? Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2021/10/vem-ska-integreras-om-etniska-svenskar-blir-en-minoritet/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. De totalitära Liberalerna. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2018/02/de-totalitara-liberalerna/ (accessed on 29 February 2023).

- Hansen, U. Finns de Plats för Försoning? Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2017/09/finns-de-plats-forsoning/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Hansen, U. Tänk Om, Mångkultur Fungerar Inte. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2018/08/tank-om-mangkultur-fungerar-inte/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Brandberg, T. Till Alla Som Tror Att ”Vi- och Dom” är Ett Argument Mot SD. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2016/02/till-alla-som-tror-att-vi-och-dom-ar-ett-argument-mot-sd/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Konservatismens nationella uppvaknande är en motreaktion mot Vänsterns Globala Utopism. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2019/07/konservatismens-nationella-uppvaknande-ar-en-motreaktion-mot-vansterns-globala-utopism/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Skulle S och SD Kunna Regera Ihop? Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2017/10/skulle-s-och-sd-kunna-regera-ihop/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Hur Attraktivt är ett Modernt Folkhem? Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2018/07/hur-attraktivt-ar-ett-modernt-folkhem/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Socialdemokraterna Har Glömt Sina Rötter. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2017/05/socialdemokraterna-har-glomt-sina-rotter/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Erixon, D. Nationell Sammanhållning Förutsättning för Frihet. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2017/11/nationell-sammanhallning-forutsattning-frihet/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Persson, H.-P.; Arvidsson, H. Med Kluven Tunga: Europa, Migrationen Och Integrationen; Liber: Malmö, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Pettersson, K. The use of national myths in the rhetoric of Nordic populist radical right parties. In Nordic Radical Right; Jupskås, A., Jungar, A.-C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. The Democratic Paradox; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brandberg, T. När Komfortliberaler och Identitetsvänster Får Styra. Available online: https://samtiden.nu/2019/12/nar-komfortliberaler-och-identitetsvanster-far-styra/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Schall, C.E. The Rise and Fall of the Miraculous Welfare Machine: Immigration and Social Democracy in Twentieth-Century Sweden; Cornell University Press: London, UK; Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hellström, A. The Populist Divide in Far-Right Political Discourse in Sweden: Anti-Immigration Claims in the Swedish Socially Conservative Online Newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022. Societies 2023, 13, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050108

Hellström A. The Populist Divide in Far-Right Political Discourse in Sweden: Anti-Immigration Claims in the Swedish Socially Conservative Online Newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022. Societies. 2023; 13(5):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050108

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellström, Anders. 2023. "The Populist Divide in Far-Right Political Discourse in Sweden: Anti-Immigration Claims in the Swedish Socially Conservative Online Newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022" Societies 13, no. 5: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050108

APA StyleHellström, A. (2023). The Populist Divide in Far-Right Political Discourse in Sweden: Anti-Immigration Claims in the Swedish Socially Conservative Online Newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022. Societies, 13(5), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050108