1. Introduction

Violence against women and girls has varied definitions, as it is multi-faceted. However, the definition from the World Health Organisation [

1] is the most recognised and globally accepted definition. WHO defines domestic violence as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life”. The United Nations [

2,

3], on the other hand, define domestic violence or abuse “as a pattern of behaviour in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner,” They posit that abuse might be physical, sexual, emotional, economic or psychological actions or threats of actions that influence another person. It further defines sexual violence “as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object, attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching and other non-contact forms” [

1]. Domestic abuse, domestic violence or intimate partner violence can be used interchangeably; however, for this conceptual study, the term “domestic abuse” will be adopted. Harmful practices as a subset of violence against women and girls will also be examined.

According to Chan [

4], sexual violence is widely acknowledged as a violation of human rights and a public health concern that occurs across societies and cultures, in peace and conflict, and many social settings such as the home, workplace, schools and communities. Unlike the common myth that strangers often perpetrate rape and sexual assaults, statistics show that these crimes are predominantly perpetrated by trusted family members such as partners, cousins, etc. For child sexual abuse (CSA), trusted family or community members, including parents, siblings, and sometimes religious leaders, are often the perpetrators [

5]. It is important to state that there are exceptions to this assertion, as this is not always the case.

Supporting the views of [

4,

6], noted that sexual violence incidents are diverse in circumstances and settings. These could be sexual violence in a romantic relationship, including marriage and dating relationships; rape in non-romantic acquaintances; sexual abuse by those in positions of trust such as clergy, professionals, teachers, medical practitioners, and strangers; multiple perpetrator rapes; sexual trafficking; unwanted sexual contact; and sexual abuse of people with disabilities, among others. These depict the unequal imbalance of relationships between men and women. The keyword in these varied circumstances is consent, which is either not given or not partially given [

7]. Notably, although both genders are affected by domestic and sexual violence, women and girls are disproportionately more affected than their male counterparts.

The Home Office shows that one in four women and one in six men have been victims of domestic and sexual abuse in England and Wales. In addition, one in nine or ten women experiences domestic violence in a year [

8]. Despite the recent awareness and campaign to increase the inclusion of men in combatting violence against women and girls, statistics show that most domestic abuse victims are women and girls [

9]. Women are also more likely to be repeat victims, threatened, harassed, assaulted, and at greater risk of death pre- and post-separation or divorce ([

10,

11]).

Netto [

12], Valente& Wight [

13] concluded that domestic and sexual abuse have both damning physical, psychological, and health consequences for the survivors and children in these relationships. Domestic violence survivors often suffer from low self-esteem and mental health issues, and children from these relationships also suffer from physical assault by the same perpetrators [

14]. The health implications of sexual violence can range from short- to long-term consequences, including gastrointestinal symptoms, genital injuries and cardiopulmonary symptoms such as palpitations and shortness of breath. Long-term consequences include genital irritation, fibroids, and chronic pelvic pain among others [

15].

The aims of this conceptual study is to demonstrate the establishment of specialist services as an example of good practice in the UK; to depict the resultant effects of the establishment of specialist services on disclosures by the BME communities, using Yellow Door as a case study; and to advocate the need for the establishment of more local specialist services away from major cities such as London, Birmingham and Manchester, particularly in locations with a high population in the BME demographic. Finally, this study aimed to re-emphasise the role of collaborative approaches in preventing and reducing domestic abuse and harmful practices. Firstly, this study explains the progress made by charities in post-war Britain in supporting domestic and sexual abuse victims in the United Kingdom; secondly, a brief background of Yellow Door and the two specialist services are discussed; thirdly, BME-specific domestic and sexual abuse will be explained; fourthly, the specialist service approach (SSA) is explored as a framework for collaborative interventions; and lastly, Yellow Door, as a case study of multi-agency collaboration in Southampton, is discussed. Recommendations will be made to facilitate more disclosures and create referral pathways for potential clients.

2. The Role of Charities in Tackling Domestic Violence in Post-War Britain

Domestic violence or abuse was neither in the academic discourse nor incorporated into government policies for a long time in the United Kingdom until very recently (the last three decades). It was considered a private affair that should not be brought to the public domain [

16]. The last three decades have seen a significant shift in the understanding, approach and response to domestic violence, nationally and internationally. Governments and international organisations (such as the United Nations and World Health Organisation), and local charities in the UK; specifically, have been instrumental to this shift. For instance, in Britain, 150 years ago, it was legal for a man to beat his wife, provided that he used a stick no thicker than a thumb. Until much attention was given and awareness raised to combat this social problem, no policies or legislation were available to protect domestic violence victims [

10].

Since the 1990s, the approach to domestic violence has taken a new outlook, both internationally and locally. This approach is evidenced through several international instruments enacted by international organisations such as the United Nations [

17]. The 1995 Fourth World Conference marked a defining moment for the achievement of gender equality, which encapsulated everything gender-related, including violence against women [

18]. The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women at the Beijing Conference provided a global framework in which governments from different countries built policies and frameworks for addressing violence against women and girls (VAWG), including domestic and sexual violence [

19].

Similarly, the Istanbul Convention, signed in May 2011, emphasised that governments must address all forms of violence against women and girls by condemning this societal problem. The Istanbul Convention defines VAWG “as all forms of violence within the definition experienced by women and girls under 18. This includes domestic violence-all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence occurring in the family, domestic unit or between current or former spouses or partners” [

20]. This definition has been adopted as the standardised framework for both statutory and non-statutory agencies, “which is important for funding, commissioning and multi-agency working” [

21].

In the United Kingdom (UK), for instance, feminist policies and movements helped bring the issue of domestic violence to the fore through debates, policymaking and human rights campaigns; a plethora of research attests to this. Subsequently, their campaigns, lobbying and advocacy resulted in the provision of refuges in the 1970s for supporting women who had experienced domestic violence. Due to the massive influx into the refuges, more refuges were established. This influx also birthed Women’s Aid and other charities. Other non-governmental organisations have since been established in the UK to cater to domestic and sexual violence victims’ needs [

22].

According to Harwin [

10], “Women’s Aid coordinates a national network of 340 local domestic violence services that support more than 500 refuge projects, helplines, and outreach services, including specialist projects for Black and ethnic minority women’’. The 1980s also saw the establishment of specialist refuges for women of colour and minority communities; these refuges were established following several campaigns by women’s organisations to specifically cater to the needs of women from these communities [

23,

24]. Researchers have further argued that globalisation has been an impetus for the extent and classification of violence against women. More opportunities have been provided for both sexes, including women and girls from all walks of life, as victims of different types of abuse ranging from entrapment, exploitation and abuse to enslavement [

22]. Boyle [

25] further corroborated the prevalence of violence against women in the UK, stating that “Police reports suggest that domestic violence is a fact of life for millions of women in the UK” [

25].

Moving on from the establishment of charities supporting domestic violence victims, domestic and sexual abuse charities have since expanded their thematic areas. From policy advocacies, research focusing on women’s separation from their violent spouses or partners, women’s welfare benefits such as the Destitution Domestic Violence (DDV) visa housing provision, consultancy, national publicity and training services to emergency protection, the focus of victim support charities have since changed [

26]. This activism by these organisations has resulted in tremendous progress, including the domestic abuse act’s criminalisation and the domestic abuse bill’s passage. This has also increased in the reporting of domestic abuse offences and allegations by 65.8% in London after being reported to the Crime Prosecution Service [

10,

22].

3. BME, Domestic and Sexual Violence, and Specialist Services

Ethnic minority communities have a migration history with four main ethnicity elements: race, language, culture and religion. These elements differentiate them from their indigenous Anglo-Saxon counterparts in the United Kingdom. These factors should be considered when supporting members of these communities [

27,

28]. Siddiqui [

29] argued that the high rate of domestic and sexual abuse among BME could be attributed to the more significant barriers they face due to intersectional discrimination based on factors such as race, class, caste, poverty overlaps and other multiples. Graca [

30] further stated that women from these communities face additional barriers, such as insecure immigration status. In addition, the socio-cultural practices of non-UK nationals compared with other counterparts impede them from accessing support services.

Martin, Jahan & Habib [

31] opine that Asian women face double abuse, as they are often victimised first by the abuser and the community. The responsibility of protecting the family honour (“Izzat” in Urdu) and the avoidance of bringing shame (“Sharam” in Urdu) to the family debar women from these communities from escaping domestic and sexual abuse [

32]. Since communities are commonly complicit in these hidden crimes, fear of reprisals from the community silence many women and girls from reporting [

33]. The study by Mulvihill, Walker, Hester & Gangoli [

34] identified that religion is adopted as a manipulative tool by both families and religious organisations to convince women from BME backgrounds to remain in abusive relationships. These foundations stem from religious texts which justify women’s reasons to only leave a marriage on the grounds of death or infidelity [

35]. Conversely, in Islam, men can divorce a woman by saying the word ‘‘talaq’’ three times, which gives men a kind of coercive control in an abusive relationship and makes women perpetual victims [

36].

Netto [

12] explored an underreported barrier to reporting in the BME communities. She argued that this is based on the importance of honour attached to the family. Some women from these communities have internalised the feeling of inferiority to their male counterparts in the family and, as such, feel responsible for the different forms of abuse, such as the physical, emotional and sexual abuse they experience from family members and in-laws. Some of these barriers sometimes hinder them from leaving abusive relationships and seeking professional support.

However, Ahmed [

37] differs in his findings, as he concludes that Black and minority ethnic communities come from a wide range of varied backgrounds, including religious, cultural [

38] and socio-economic backgrounds, compared with other communities. As such, different services should be provided for these communities that are different from the mainstream communities. Chand &Thoburn [

39] further observed a shortage of preventative work, specialist services and service delivery for children and families from Black and minority ethnic communities across the UK. VAWG [

21] arrived at a somewhat different conclusion. Their research concluded that specialist services, particularly community-based women’s organisations, are pivotal to the prevention of and intervention in VAWG. Their conclusion is due to the familiarity with the local terrain and their ability to build a framework around education, innovation and prevention. Larasi [

26] further stressed that due to the knowledge of the local communities, the establishment of specialist services for Black and minoritized women and girls are critical. These services provide advocacy and frontline responses alongside campaigning and lobbying at the national front, which, in turn, translate into positive outcomes such as more disclosures, holistic support and rebuilding their lives after the abuse.

Despite the proliferation of women’s groups and organisations supporting women experiencing domestic abuse and the increase in the reporting of domestic abuse among Black and minority ethnic communities, evidential research has shown underreporting or no reporting at all for women experiencing domestic and sexual abuse in the BME communities exists [

40]. Specific vulnerabilities such as insecure immigration status [

41], cultural and religious factors, and policies and structures such as having no recourse to public funds are the principal factors contributing to the underreporting of domestic violence within these communities [

42].

Gangoli, Bates,& Hester [

43] argued that the most common type of abuse experienced and reported by BME women was all-encompassing abuse and different from other communities. In addition to physical, financial, sexual and emotional abuse experienced by other communities, some members from the BME communities further experience other harmful practices such as honour-based abuse, forced marriages, breast flattening, and Female Genital Mutilation(FGM), among others [

44]. They are, thus, faced with a two-edged sword of abuse. It was further observed that compared with their White British counterparts, the disclosure rate of sexual-related offences experienced by both adults and children from BME groups was low due to the culture of ”shame” linked to issues around rape and assault [

45]. Dartnall & Jewkes [

6] attributed the underreporting of domestic and sexual violence among the BME community to factors such as having fewer specialist services, a lack of awareness of specialist services, cultural and religious barriers, immigration status and the different legal and cultural requirements in their home countries [

43].

The End Violence against Women Coalition remarked on the dearth of research into the impact of specialist services on the reporting and disclosure of domestic and sexual abuse among BME communities [

46]. They further highlighted how the nature of the cultural advocacy and support provided impacts domestic and sexual disclosures and reporting. Hence, the need to investigate this research gap. There is less emphasis on programmes focusing on preventative work and education of BME communities and the long-term consequences of domestic and sexual abuse on their members. Solutions to tackle this problem within the community are also missing [

47].

4. Yellow Door—A Brief Background and Two Specialist Services

Yellow Door (YD) is a domestic and sexual abuse charity established 36 years ago as a rape crisis service in Southampton, United Kingdom. Since its inception, it has expanded to provide a range of prevention and support interventions to victims of domestic abuse and other forms of interpersonal harm or discrimination.

Yellow Door is an inclusive charity that works with any gender and all age groups. It also supports victims of domestic and sexual abuse in whatever form, at whatever stage or form of life, regardless of the time, historical or recent.

Most of the services provided by Yellow Door are from the central premises in Southampton or Southampton in general; other services are, however, provided across some areas in Hampshire, depending on funding availability.

Yellow Door provides domestic and sexual abuse support through six different services, namely therapeutic services, domestic abuse services, independent sexual violence advisory services (ISVA), diversity and inclusion advocacy (DIA), the helpline, and prevention and education [

48].

In addition, to specifically cater to the needs of the Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities within Southampton, a bridged service between the diversity and inclusion services and the independent sexual violence advisors service was created. This research focused on this bridged service between the ISVA and DIA services, catering to the domestic and sexual concerns of the victims and survivors from these communities. For context, the terms BAME or BME will be briefly explained to understand this demographic. BAME or BME represents the Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities or those with BME (Black and minority ethnic) backgrounds. To better support clients from these backgrounds with additional needs and specific vulnerabilities, YD collaborates with other statutory and non-statutory agencies across Southampton and Hampshire to provide them with holistic support.

4.1. Yellow Door Specialist Services—ISVA/DIA Services

4.1.1. The Independent Sexual Violence Advisory Service (ISVA)

Both the DIA and ISVA services within YD use the empowerment or client-led approach, building on evidential research of its effectiveness to provide holistic support to clients [

49]. The empowerment-oriented approach is predicated on the two social work principles of “self-determination and the dignity and worth of human beings”. This approach postulates that clients should be involved in decision-making regarding their service delivery and have access to quality holistic services best suited to their needs and well-being [

50]. These empower clients, help them develop leadership skills and increase self-esteem [

51]. The independent sexual violence advisory service (ISVA) is an advocacy service within Yellow Door that specialises in supporting victims of any unwanted sexual experience such as sexual violence, abuse or exploitation, regardless of the incident, whether historical or recent, and regardless of age, gender or sexuality. The providers are professionally trained to provide personalised emotional and practical support to meet clients’ needs. Although they work closely with the police, they are an independent service that provides independent support to help clients make informed decisions about their next steps [

52].

ISVAs provide support with decisions, reporting to the police and health options, and support throughout the criminal justice process, depending on the client’s choice or decision. Specialist services include the children and young persons’ ISVA, the family ISVA, the male ISVA and the BAME ISVA within the ISVA services. This research, however, focuses on the BAME ISVA specialist service [

52].

4.1.2. BAME ISVA

BAME ISVA workers are specialists who support clients from Black and minority ethnic communities who have suffered sexual abuse, exploitation and violence across Hampshire. The BAME independent sexual violence advisory service within YD supports sexual violence victims, from the reporting to the investigation stage, and throughout the criminal justice process.

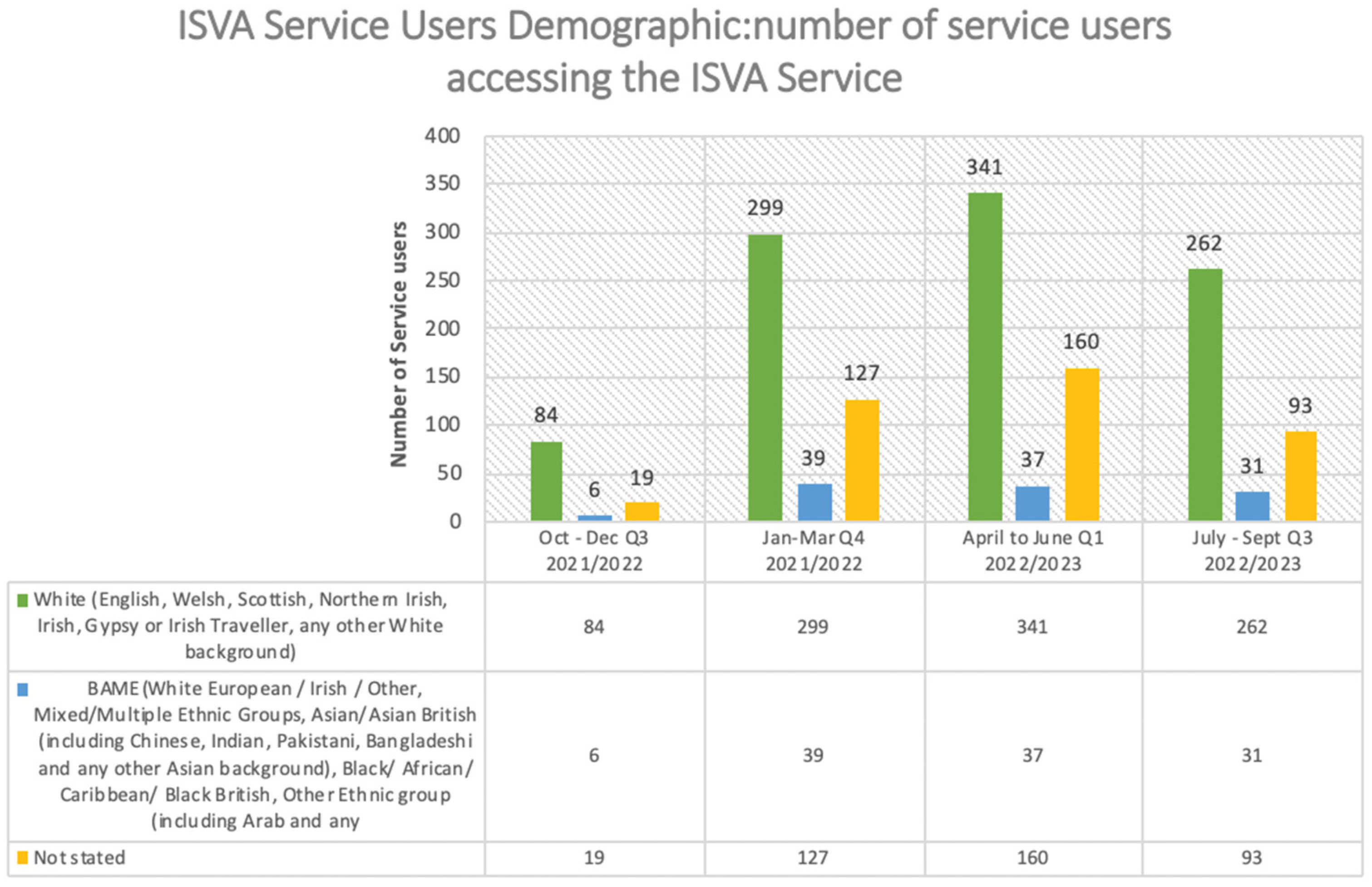

According to YD, below is a table and chart showing the ISVA service users’ demographics (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

The table above shows the number of service users per year from October 2021 to September 2022.

The third quarter shows a total of 109 service users: 84 White clients, 6 BME clients and 19 not stated. The last quarter in 2021/2022, between January to March 2022, saw a massive increase of 299 service users. This increase marked a milestone for the BME ISVA services, as the number increased from 6 in the last quarter to 39. This massive increase in service users can be attributed to the BBC report [

53], which stated that violence against women in Hampshire increased significantly in 2022. Southampton, Portsmouth and Basingstoke saw a rise in sexual violence cases, Southampton being the highest, with a total of 402. The increase in BME clients can also be attributed to the establishment of the BME specialist service in September 2021.

The first quarter of 2022/2023 saw a slight increase in service users, totalling 341 White clients, 37 BME clients and 160 not stated. The second quarter of 2022/2023 saw a relative decline in White, BME and “not stated” clients, with 262, 31 and 93, respectively.

Although the number of BME service users was low compared with their White British counterparts, the progress and increase are noteworthy, considering the barriers mentioned above experienced by this demographic. It is essential to consider that the number of those in the “not stated” category was huge in all the quarters. Although not accounted for, one can infer that BME clients are also within these numbers. Nevertheless, it is safe to conclude that the establishment of the BME ISVA service translated into an increased number of disclosures and, in turn, service users from that community.

4.2. The Diversity and Inclusion Advocacy Service (DIA)

This advocacy service within YD includes domestic and sexual abuse specialists trained to work with marginalised or disadvantaged groups or communities to address barriers, such as language, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, faith, and mental health to improve access and promote equality. Professionals within this service speak multiple languages, such as South Asian, African and European, to support and address language barriers among the minority ethnic communities they support. There are also specialist services within this service.

4.2.1. Harmful Practices

The harmful practices workers or advocates (HPWs) provide emotional and practical support to the victims or those at risk of harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, honour-based abuse and breast flattening. These specialists also support clients with complex needs and specific vulnerabilities, such as housing, immigration status and education, through one-to-one casework [

52].

4.2.2. Prevention and Education

To tackle the recurrence of domestic and sexual abuse, mainly hidden harm, the HPWs within the DIA service engage in educational sessions in primary and secondary schools in Southampton. They educate children, young people and undergraduates on harmful practices such as FGM, forced marriage, honour-based abuse and breast flattening.

These specialists also work collaboratively with other professionals in Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and Southampton (HIPS) to run webinars on HP for the police, social services, tertiary sector, education and health professionals to identify the risks and create referral pathways for clients.

4.2.3. Training

The HPW practitioners design training packages for professionals, taking factors such as the specific sector, the audience, the best-suited safeguarding protocols and relevant terminologies into consideration when delivering this training to designated safeguarding leads (DSLs), headteachers and other leads in education settings. Training and webinars are also delivered to other professionals in the health sector, including general practitioners (GPs) and midwives.

Both the ISVA and DIA services provide emotional and practical support to survivors from this community. They also raise awareness in different communities and religious organisations to encourage more disclosures and reporting. Both services also work collaboratively with other institutions, professionals and community-based organisations such as the police, the criminal justice system, Early Help, the Southampton City council and other charities in Southampton, among others.

5. Specialist Service Approach: A Multi-Agency Framework

Logar & Vargová [

54] defined specialist or women’s support services as a collection of specialist services covering a range of thematic areas in supporting the victims and survivors of domestic violence. These thematic areas ranging from women’s shelters, national women’s helplines, rape crisis and sexual assault referral centres, migrant and minority ethnic women, and independent domestic and sexual violence advocacy to intervention centres. The multi-agency approach is considered effective for preventative and early intervention in domestic abuse services at both the operational and strategic levels, resulting in holistic support, effective service delivery and positive outcomes for the service’s users [

55]. For instance, at Yellow Door, to safeguard a domestic violence victim living with the perpetrator whose life is at risk, the best practice is to secure a safe space for the client by either signposting the victim to a women’s refuge or seeking alternative accommodation. This safeguarding is achieved by collaborating with the local police, housing practitioners and refuges across the country to protect the victim. This is, of course, achieved with the client’s consent.

Cheminais [

56] provided some benefits of collaborative or multi-agency partnerships in the education sector, which also apply to other professional settings. The benefits range from “enhanced and improved outcomes for children and young people through ease of access, and support, strengthening partnership, breaking down professional boundaries and parochial attitudes, to building consensus”. Atkinson et al. [

57] also argued that the multi-agency helps to build a more cohesive community approach through the practitioners taking greater ownership and responsibility for addressing local needs jointly, thus avoiding duplication or overlap of provision.

In Southampton’s violence against women and girls sector, the multi-agency approach entails working collaboratively with the police, the criminal justice system, the witness service and other local charities with different thematic areas.

Though there are different models available to be adopted, there are, three broad models a multi-agency framework can use in executing its functions. While some use the expertise of practitioners who meet regularly, some adopt the casework method, while others engage designated workers to lead the casework [

58]. Atkinson et al. [

57] differed somewhat in their description of the multi-agency approach, arguing that there are five different “multi-agency models: decision-making groups, consultation and training, centre-based delivery, coordinated delivery, and operational-team delivery”. They further opined that different organisations or agencies adopt different models and meet for varied reasons to achieve a primary purpose or objective.

The three models described above by [

58] are adopted at Yellow Door, depending on the client’s circumstances. A case in point of using the expertise of practitioners who meet regularly to support a client is the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) meeting. This meeting is where different professionals discuss relevant information, safeguarding and potential support. These professionals could be local police, health, children’s services, housing practitioners, independent domestic violence advisor (IDVAs), independent sexual violence advisors (ISVAs) and other practitioners to protect the highest-risk domestic violence victims.

The casework approach is another method adopted by YD, as BAME ISVAs and harmful practices workers provide one-to-one casework support to the victims of harmful practices and sexual violence. ISVAs, for instance, support clients from the pre-reporting stage and throughout the police investigation to the trial and post-trial stages, unless otherwise requested by the client. Designated workers with specific expertise also support clients within the purview of their expertise. BAME ISVAs support BAME clients, whereas children’s ISVAs support child clients. This approach is used to achieve tailored support. In the case of victims of HP, only the HPWs equipped with the right expertise are designated to support these clients. The HPWs are also active stakeholders in the HP operational group and the FGM Zero Tolerance Day in Southampton.

6. Yellow Door and Multi-Agency Collaboration in Southampton

Collaborative working in combating domestic and sexual abuse requires sufficient funding, alongside a strong partnership among statutory services such as the police, housing, health services, the Crown prosecution service, the criminal justice system, children’s and social services, and commissioners, among others [

59]. Non-statutory agencies such as charities with similar thematic areas but different jurisdictions are also pivotal in providing holistic care and support for clients and survivors. These factors are also considered the basis of local funding for local organisations [

21]. Some organisations and institutions involved in the collaborative efforts in different ways with Yellow Door in Southampton, United Kingdom, are described below.

6.1. The Police

The police support different areas of DV, ranging from honour-based abuse, domestic abuse, female genital mutilation, and breast flattening, among others. For instance, Yellow Door and the police co-chair the Harmful Practices Operational Group. YD also works closely with the Chief Inspector, including partnering on the FGM Crime Stoppers initiative and engaging with police constables to reach communities.

Similarly, within the police is a special unit called “Amberstone”. They are specially trained officers (also known as STOs) who have been specially trained to support sexual violence victims from the reporting to the investigation stage.

6.2. Specially Trained Officers (STOs)

The STOs are also called sexual offences investigative techniques trained officers (SOIT officers), depending on the county or police force involved. STOs are responsible for providing clients with practical and emotional support throughout the investigation process. Some of the primary responsibilities of the STOs are to take the victim’s initial report of the incident and statement and signpost clients to the relevant agencies, including sexual violence specialist services such as the independent sexual violence advisory service. STOs also ensure that the medical needs of sexual violence victims are met; this is accomplished by referring clients to sexual assault referral centres. They educate clients on the criminal justice system, provide relevant information regarding the case and safeguard clients at risk. For clients contemplating reporting, YD works collaboratively with the STOs to provide “Anonymous Advice Meetings’’, where the clients meet with the STOs in a relaxed environment to gain clarity about the criminal justice process and to decide their next steps [

60].

6.3. Sexual Assault Referral Centres

The sexual assault referral centres (SARC) are medical sexual violence health centres across the nation targeted at anyone who has experienced sexual violence. They provide medical treatment and forensic medical examinations. The SARC is a 24 h service and a collaboration between the police, the National Health Services and charities. SARC referrals can be made by specially trained police officers or ISVA services, or victims of sexual violence can report the incident independently without the involvement of the police. Forensic examinations in these centres can be kept for a while, regardless of the decision to report or not [

60].

6.4. Southampton City Council

Within Southampton City Council, a team of professionals is dedicated to supporting high-risk clients who may be victims of VAWG, such as domestic abuse, honour-based abuse, forced marriage, female genital mutilation and sexual violence. The Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH) in Southampton provides “triage and multi-agency assessment of safeguarding concerns” [

61] This team protects the most vulnerable children and adults from harm, neglect and abuse by meeting goals related explicitly to safeguarding [

61]. The purpose is to respond quickly to safeguarding concerns about vulnerable children. It also aims at partnerships, collaborative communication and reducing inappropriate referrals and re-referrals. MASH referrals are often sent from YD to the local authority to protect and support vulnerable children, adults and families to ensure holistic support.

6.5. Other Agencies

YD adopts a “Coordinated Community Response (CCR), a coordinated response aimed at reforming, improving and coordinating institutional responses to domestic violence within the community” to support clients holistically [

54]. Thus, YD collaborates with other community-based statutory and non-statutory agencies to support the needs of clients outside the jurisdiction of Yellow Door. Some of these services and institutions are The University of Southampton, Early Help, general practitioners (GPs), midwives, the police and housing for the DIA service. Witness care and witness services within the Crown prosecution service, also work closely with the ISVA service.

Despite these collaborations, both services encounter some challenges when delivering services. For instance, the DIA service’s one-to-one advocacy support, was impacted by COVID-19, as the clients’ movements were restricted. The service adopted Zoom sessions during this period and has continued to adapt to hybrid working modes. In addition to HP, some of our clients have multiple vulnerabilities, such as learning disabilities, visual impairments, hearing difficulties, etc. Due to these added complexities, engaging via telephone or Zoom could be logistically challenging. The HPWs adapt to the challenge of medium and location continually.

Another major challenge is the language barrier. Some of our service users have limited command of the English language, thus making support a challenge. The HPWs speak European, South Asian and African languages that are well suited to the clientele. In the event of the non-availability of some languages, the HPWs use certified interpreters to support clients.

Disclosures of forced marriages and honour-based abuse often result in some clients seeking alternative accommodation separate from the perpetrators. The HPWs mitigate this housing challenge by working collaboratively with the police and refuge workers to provide temporary accommodation in refuges. The HPWs also work closely with housing officers to provide permanent accommodation as required.

With respect to the BME ISVA service, one of the foremost challenges is the long duration of the criminal justice process, which sometimes discourages clients from reporting or results in the withdrawal of cases. The BME ISVAs confront this by managing clients’ expectations from the outset through anonymous advice meetings. Expectations and outcome are also managed through one-to-one support of the clients throughout the investigative process. Unfavourable trial and post-trial outcomes can also sometimes negatively impact or traumatise clients. Signposting clients to the appropriate trauma-informed service and counselling services within and outside Yellow Door often tackles this challenge.

7. Discussion

According to the British Broadcasting Corporation [

53], violence against women in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight increased to 37,137 offences in 2021. Rape incidents in 2021 increased to 402 in Southampton, with the highest rate; one in six rapes in Hampshire was committed in Southampton. They also observed that Southampton, Portsmouth and Basingstoke have higher numbers of other sexual offences. Hence, the need to establish additional domestic and sexual abuse specialist services to address these challenges in Hampshire and across the United Kingdom. Yellow Door, a community-based domestic and sexual abuse charity in Southampton, has been addressing these societal concerns by establishing varied services addressing specific domestic and sexual-related concerns and issues. YD has seen a 91% increase in referrals, with Southampton ranking as the second-highest city for sexual offences in England, and the figure has increased by 240% in the last five years [

48]. Thus, YD and various agencies must continue to work collaboratively to combat this challenge and make the city safer for women and girls to reside in.

Disclosures among the BME communities are challenging because of the factors mentioned above. Some clients within these communities have also experienced mistrust from service providers in the past, thereby leading to dire consequences from family and community members.

Establishing more specialist services serve as a safe space for supporting BME victims and survivors. The establishment of more specialist services for Black and minority ethnic communities in more local areas across the United Kingdom will cater to their specific needs and encourage more disclosures and reporting of domestic and sexual abuse in these communities.

Increasing long-term funding for existing specialist services will result in the continuity of these services, as clients will be confident that their needs will be addressed long-term. This approach will potentially reduce the observed underreporting of domestic and sexual abuse within these communities.

Thus, to provide more opportunities for disclosures, more specialist services should be established to safeguard the clients and ensure that the client’s trust is gained. The assurance of confidentiality in handling their cases is also critical, as disclosures could potentially result in honour-based abuse by families and community members.

More advocacy strategies are required to incorporate more community stakeholders such as clergy and local community leaders in the combat against domestic and sexual abuse among BME. These stakeholders are critical to effecting the desired change of eliminating domestic and sexual violence within the BME communities and in the United Kingdom.

Increased training on cultural competence for statutory and non-statutory professionals such as the police, local authorities and other practitioners should be advocated. This training will ensure that clients from these communities feel confident and safe enough to disclose cases and are also assured of non-judgmental or stereotypical interventions by professionals.

More specialist refuges or women’s shelters specific to the BME communities should be established across the country to cater to the specific needs of this demographic of clients. These shelters will serve as safe spaces and safeguard victims from perpetrators.

The four crucial peculiarities of BME clients: race, culture, language and religion, should always be considered whilst providing interventions for these clients’ demographics. Considering these factors will ensure the provision of holistic support.

8. Conclusions

This research has highlighted the collaborative approaches to addressing domestic and sexual abuse among the Black and minority communities in Southampton, England, using two specialist services within Yellow Door as case studies. The need for specialist services for minority ethnic groups to better cater to their needs based on their specific vulnerabilities was discussed. Factors such as immigration status, language barriers, religion, honour-based abuse and other vulnerabilities which differ from the mainstream community, were also considered.

Yellow Door’s multi-agency approach with statutory and non-statutory organisations across Southampton to support the varied and complex needs of clients from Black and minority ethnic communities through various strategies such as prevention and education was also highlighted. This research has observed the effectiveness of the specialist service approach, from a practitioner’s standpoint. Unlike in the past, where domestic and sexual abuse in Southampton and Western Hampshire within the Black and minority ethnic communities was underreported, both specialist services within YD have seen more referrals from professionals and community groups. Self-referrals from survivors regarding both historical and recent sexual abuse have also been observed. Disclosures of harmful practices such as forced marriage, honour-based abuse and female genital mutilation have also increased in these communities.

Clients have also attested to the effectiveness of the casework interventions received from both services, resulting in improved mental and physical well-being. Thus, it is safe to say that establishing specialist services for Black and minority ethnic communities translates into more disclosures and reporting by these communities, and specialist casework interventions promote improved well-being.