Telegram Channels and Bots: A Ranking of Media Outlets Based in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

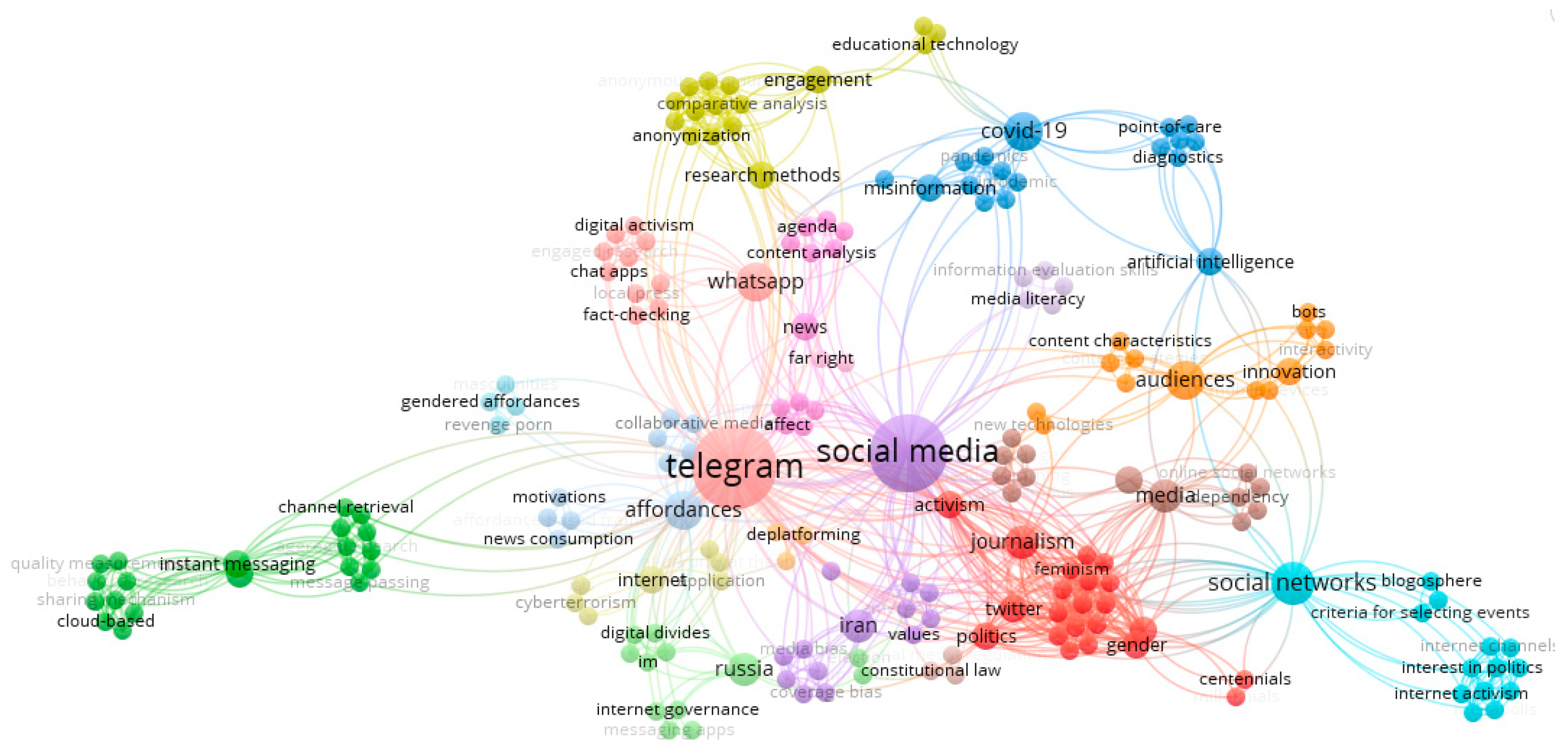

2. Telegram and the Communication Journals

3. Materials and Methods

- We searched for the web version of the media outlets that post news or link to their Telegram channel, as almost all of them link to their Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram profiles, and some to their YouTube channel and other applications. Surprisingly, we found that only three media outlets post news and provide access to their Telegram channel;

- We searched Telegram for the same media outlets and found that 30 of the 42 headers included a Telegram channel, but only eight were verified by Telegram;

- We refined the initial list of 30 channels and found that four of them had been inactive for more than six months;

- We trimmed the list to 26 channels after excluding the four inactive channels;

- In the 26 selected channels, we identified their date of creation by clicking the options button at the top-right of the screen, selecting “go to the first message” from the drop-down lists, and checking the record of the date of creation. In all of them, this date is specified before the first message;

- The number of subscribers of each channel has been registered as of 1 January 2022. The information on the number of subscribers is public data, which can be retrieved from the channel.

- Below, we searched the post number of each channel on the same date. This information is not expressly indicated in the general information of the channel but can be accessed by requesting a news link, which indicates the order number of its publication. To gather information on the total number of publications of each channel, we recorded the order number of the first news item published;

- After gathering the name, the date of creation, and the number of subscribers and posts, we divided the number of subscribers by the total number of posts of each channel, thereby calculating the S/P ratio, which will be the object of our analysis;

- Finally, we made the final table, ranking the channels by the number of subscribers from highest to lowest;

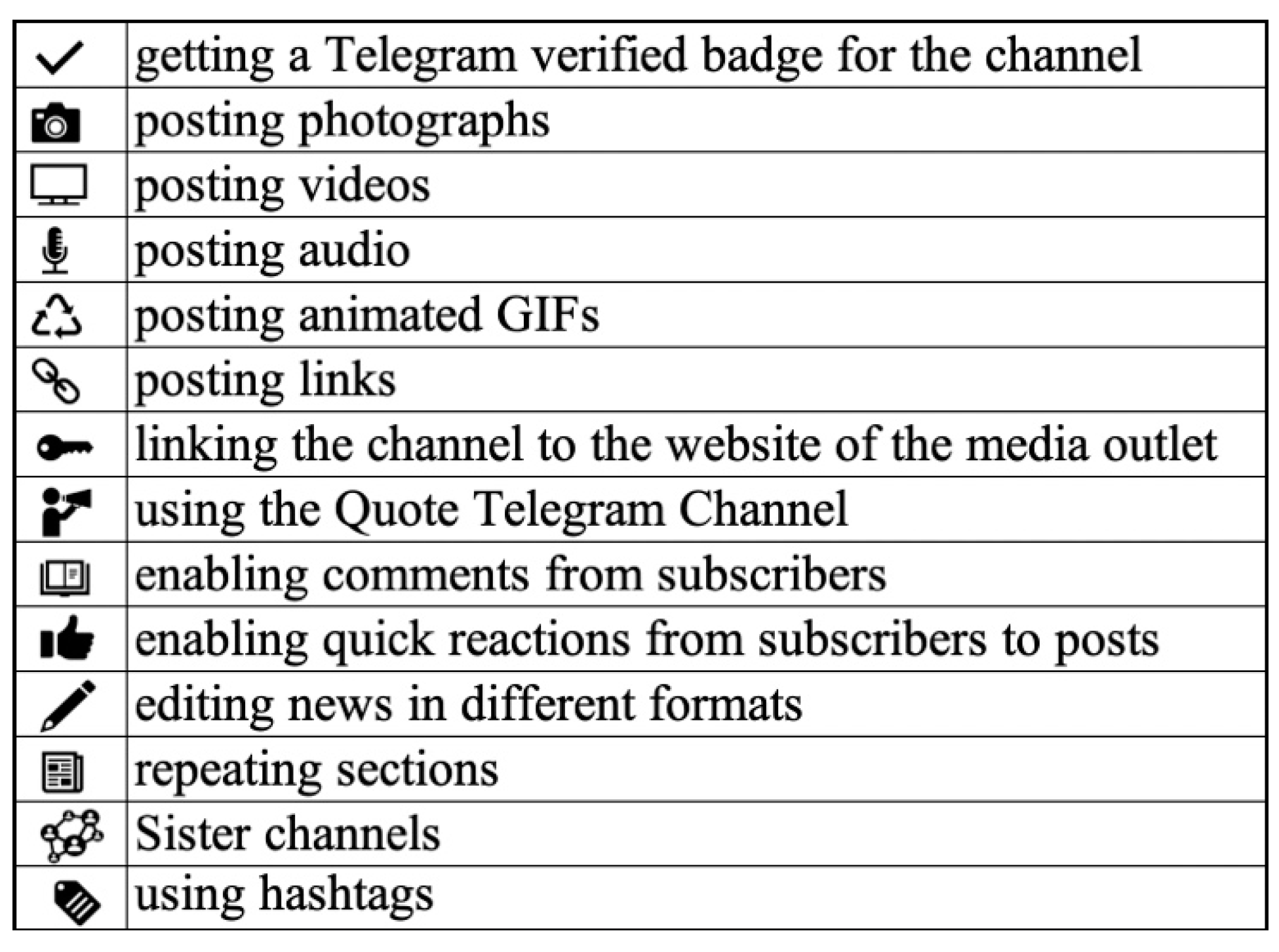

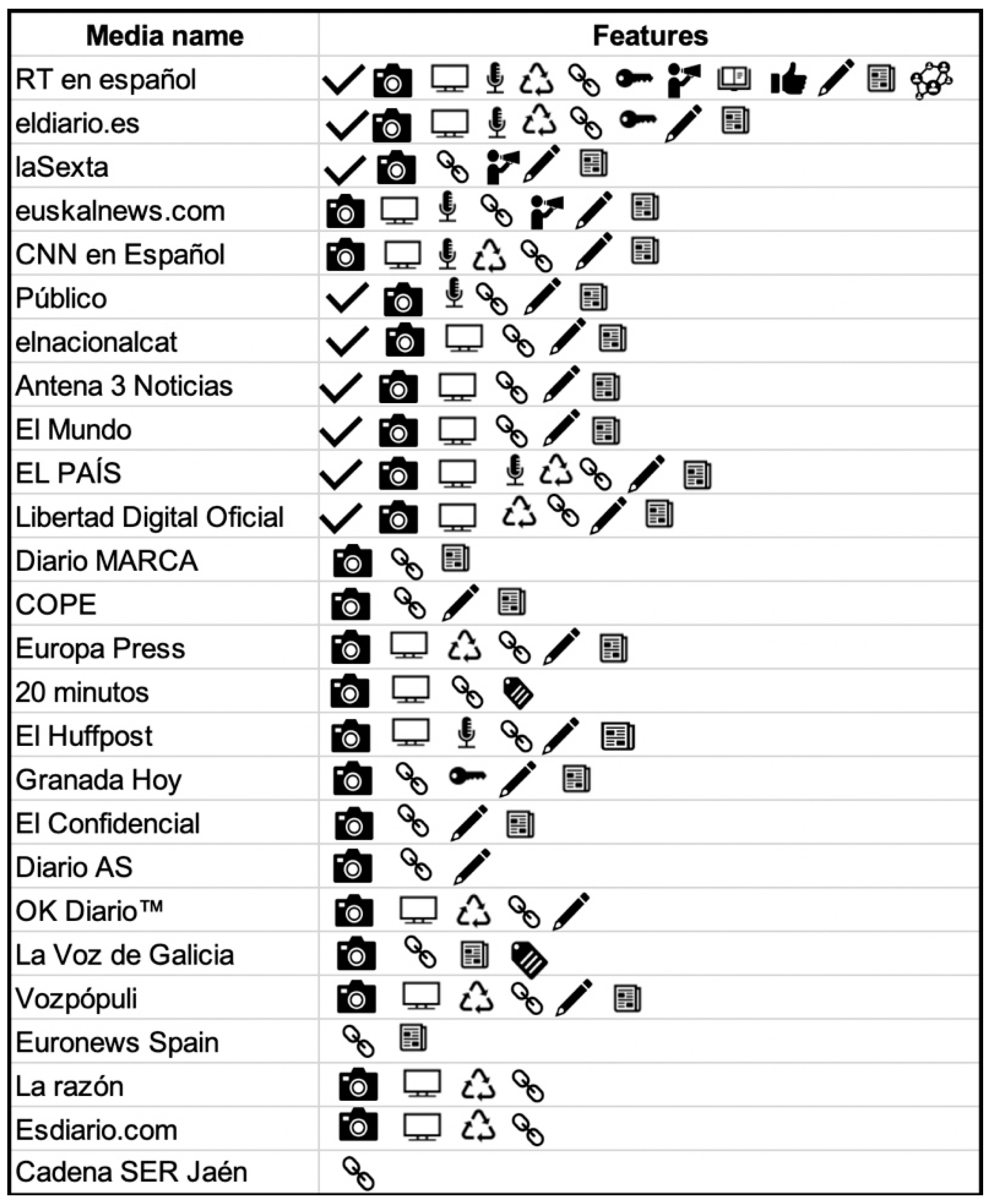

- We collected other types of additional data, such as the number of photos, videos, links, comments, sections, and hashtags, among others. Several of them can be quantified, but to avoid complicating the analysis, we have only identified them through a series of icons;

- The second author performed the original data collection. Subsequently, the first author conducted a complete quality control check for errors and omissions.

4. Results

4.1. Media Ranking

- An initial period starting at the end of 2015 and ending at the beginning of 2017, in which the first nine media are launched—eldiario.es, Euronews Spain, El Mundo, El Huffpost, EL PAÍS, CNN en Español, Público, RT en español, and elnacionalcat;

- An intermediate period, from the spring of 2018 till the summer of 2019, during which five channels started-El Confidencial, 20 minutos, Libertad Digital Oficial, Diario AS, and Diario MARCA;

- A more recent period, during the ongoing pandemic, from April 2020, under lockdown, till March 2021, in which the remaining 12 were launched-laSexta, euskalnews.com, La Voz de Galicia, Antena 3 Noticias, Esdiario.com, La razón, COPE, Granada Hoy, OK Diario™, Europa Press, Cadena SER Jaén, and Vozpópuli.

4.2. Other Features

5. Discussion

- TikTok

- Instagram

- Facebook

- Youtube

- Twitter

- V.K.

- Snapchat

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In Scopus, we have delimited the subject category Communication with a long query. See at: https://www.ugr.es/~victorhs/tquery.txt, accessed on 6 August 2022. |

References

- Wijermars, M. Selling internet control: The framing of the Russian ban of messaging app Telegram. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 25, 2190–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Saldaña, M.; Tsyganova, K. Subversive affordances as a form of digital transnational activism: The case of Telegram’s native proxy. New Media Soc. 2021. Onlinefirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Lim, M.; Kenin, J. The Telegram App Has a Global Doxing Issue. NPR. 29 September 2022. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2022/09/29/1126022504/the-telegram-app-has-a-global-doxing-issue (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- D’Cruze, D. WhatsApp Groups Can Now Support up to 1024 Members and Conduct In-Chat Polls. Bussiness Today. 3 November 2022. Available online: https://www.businesstoday.in/technology/news/story/whatsapp-groups-can-now-support-up-to-1024-members-and-conduct-in-chat-polls-351695-2022-11-03 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Singh, M. Telegram Tops 700 Million Users, Launches Premium Tier. Techcrunch. 19 June 2022. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2022/06/19/telegram-tops-700-million-users-launches-premium-tier/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Porter, J. Telegram Gains 70M New Users in Just One Day after Facebook Outage. The Verge. 6 October 2021. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2021/10/6/22712191/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Baumgartner, J.; Zannettou, S.; Squire, M.; Blackburn, J. The Pushshift Telegram Dataset. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Atlanta, GA, USA, 8–11 June 2020; Volume 14, pp. 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wate, Y. How to Create a Telegram Channel: Step-by-Step Guide. Technology Personalized. 10 June 2022. Available online: https://techpp.com/2022/01/08/how-to-create-telegram-channel-guide/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Fernández, Y. Canales de Telegram, GUÍA a Fondo: Qué Son, Cómo Funcionan, Qué Puedes Hacer Con Ellos y Cómo Crearlos. Xataka. 8 May 2022. Available online: https://www.xataka.com/basics/canales-telegram-guia-a-fondo-que-como-funcionan-que-puedes-hacer-ellos-como-crearlos (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Rubina, V.B. Telegram—Channels as Basic Ingredients of Telegram Messenger Success. Ideas Innov. 2020, 8, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalyova, M. What News Media Need to Know to Get Started on Telegram. The Fix. 2 January 2021. Available online: https://thefix.media/2021/2/1/news-org-need-to-love-telegram (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Adwani, K. Telegram Cloud Storage Review (2022)—FREE Unlimited Cloud Storage? 6 June 2022. Available online: https://kripeshadwani.com/telegram-cloud-storage (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Hadian, S. How to Get a Verified Badge at Telegram? The Blue Checkmark. Virlan. 13 October 2022. Available online: https://virlan.com/en/verification/how-to-get-a-verified-badge-at-telegram-the-blue-checkmark/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Piedra-Salomón, Y.; Olivera-Pérez, D.; Herrero-Solana, V. Evaluación de la investigación Cubana en Comunicación social: ¿Reto o necesidad? Transinformação 2016, 28, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, H. Fandom in My Pocket: Mobile Social Intimacies in WhatsApp Fan Group. In Mobile Media and Social Intimacies in Asia; Cabañes, J.V., Uy-Tioco, C.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; p. 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, A.; Keshavarz, H. Media literacy and the credibility evaluation of social media information: Students’ use of Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2021, 71, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E. Extensive use of online social networks: A qualitative analysis of Iranian students perspectives. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2019, 15, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmasetya, P.; Wirani, Y.; Rahmah, A. Blended Learning with Telegram: An Approach using Soft System Methodology to Solve Multi-Perspective Problem in Learning Limitation. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Informatics and Computing ICIC 2019, Semarang, Indonesia, 16–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.; Chahooki, M.A.Z. Telegram group quality measurement by user behavior analysis. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, I.A.; Medvedeva, M.V.; Hradziushka, A.A. Anonymous Communication Strategy in Telegram: Toward Comparative Analysis of Russia and Belarus. In Proceedings of the 2021 Communication Strategies in Digital Society Seminar, ComSDS 2021, St. Petersburg, Russia, 14 April 2021; pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, S.R.; Molaei, H. Election Journalism: Investigating Media Bias on Telegram during the 2017 Presidential Election in Iran. Digit. J. 2020, 8, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, H. Telegramming News: How have Telegram channels transformed the journalism in Iran? Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Derg. 2018, 31, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, H. Decoding Telegram: Iranian Users and “Produsaging” Discourses in Iran’s 2017 Presidential Election. Asiascape Digit. Asia 2020, 17, 88–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela, C. Un Viaje a Los Circuitos de POLITIBOT, El Bot Que Genera Adictos a La Política, Ahora También en Facebook Messenger. Xataka. 13 March 2017. Available online: https://www.xataka.com/especiales/un-viaje-a-los-circuitos-de-politibot-el-bot-que-genera-adictos-a-la-politica-ahora-tambien-en-facebook-messenger (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Sánchez Gonzales, H.M.; Sánchez González, M. Análisis de la funcionalidad y usabilidad de las visualizaciones de información online de Politibot’. Icono14 2018, 16, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Gonzales, H.M.; Sánchez González, M. Los bots como servicio de noticias y de conectividad emocional con las audiencias. El caso de Polibot. Doxa Comun. 2017, 25, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, O.V. Online Political Communication of Youth from Russian Megapolises. Galact. Media J. Media Stud. 2021, 3, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, S.; Asher, N.; Mauw, S. Examining Linguistic Biases in Telegram with a Game Theoretic Analysis. In Disinformation in Open Online Media, Proceedings of the Third Multidisciplinary International Symposium, MISDOOM 2021, Virtual Event, 21–22 September 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 29, pp. 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo-Cabrera, M. #Lasperiodistasparamos, gestación de una conciencia profesional feminista. El Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krona, M. Collaborative Media Practices and Interconnected Digital Strategies of Islamic State (IS) and Pro-IS Supporter Networks on Telegram. Int. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 1888–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrasad, H.M.; Nurdin, M.A.; Chaidar, A.; Mulky, M.A.; Zulkarnaen, I. Virtual jihadism: Netnographic analysis on trends of terrorism threats. SEARCH 2020, 12, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Urman, A.; Katz, S. What they do in the shadows: Examining the far-right networks on Telegram. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 25, 904–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R. Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. Eur. J. Commun. 2020, 35, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Molina, O.; Fuentes-Cancell, D.R.; García Hernández, A. El engagement en la educación virtual: Experiencias durante la pandemia COVID-19. Texto Livre 2021, 14, e33936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daramola, O.; Nyasulu, P.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.; Moser, T.; Broomhead, S.; Hamid, A.; Naidoo, J.; Whati, L.; Kotze, M.; Stroetmann, K.; et al. Towards AI-Enabled Multimodal Diagnostics and Management of COVID-19 and Comorbidities in Resource-Limited Settings. Informatics 2021, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranav, M. A Relationship-Centered and Culturally Informed Approach to Studying Misinformation on COVID-19. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, C.O.; Fasae, J.K. Social media and the spread of COVID-19 infodemic. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2021, 71, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, P.; Sedano Amundarain, J.A. WhatsApp como herramienta de verificación de fake news. El caso de B de Bulo. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1384–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Gonzales, H.M.; Martos Moreno, J. Telegram como herramienta para periodistas: Percepción y uso. Rev. Comun. 2020, 19, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learreta, M.G.; Meso Ayerdi, K.; Pérez Dasilva, J.A.; Mendiguren Galdospin, T. La incidencia de la edad y el género en los hábitos de uso de las redes sociales en la profesión periodística. El caso de centenials y milenials. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2021, 79, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Solana, V.; Trillo-Domínguez, M. Twitter Brand-Directors: El efecto marca en las redes sociales de los directores de medios españoles. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico 2014, 20, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann-Argueta, J. El País Encabeza la Audiencia de Medios Digitales Seguido de 20minutos Y ElDiario.es. In Digital News Report 2021; Available online: https://www.digitalnewsreport.es/2021/el-pais-encabeza-la-audiencia-de-medios-digitales-seguido-de-20minutos-y-eldiario-es/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Jalilvand, A.; Neshati, M. Channel retrieval: Finding relevant broadcasters on Telegram. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimam, S.M.; Alemayehu, H.M.; Ayele, A.; Biemann, C. Exploring Amharic Sentiment Analysis from Social Media Texts: Building Annotation Tools and Classification Models. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain, 8–13 December 2020; pp. 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.; Hohner, J.; Greipl, S.; Girgnhuber, M.; Desta, I.; Rieger, D. Far-right conspiracy groups on fringe platforms: A longitudinal analysis of radicalization dynamics on Telegram. Convergence 2022, 28, 1103–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, J.; de Winkel, T.; Schäfer, M.T. Deplatformization and the governance of the platform ecosystem. New Media Soc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlfeld, R.; Bauerfeind, F.; Braglia, I.; Butt, A.; Dietz, A.-L.; Drexel, D.; Fedlmeier, J.; Fischer, L.; Gandl, V.; Glaser, F.; et al. Communicating COVID-19 against the Backdrop of Conspiracy Ideologies: How Public Figures Discuss the Matter on Facebook and Telegram; Report; RatSWD: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, B. Zwischen Protest und Parodie: Strukturen der »Querdenken«-Kommunikation auf Telegram (und anderswo). In Die Misstrauensgemeinschaft Der »Querdenker« Die Corona-Proteste Aus Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaftlicher Perspektive; Reichardt, S., Ed.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, KY, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, R.M.; Salles, D.; Barros, C.E. We love to hate George Soros: A cross-platform analysis of the Globalism conspiracy theory campaign in Brazil. Convergence 2022, 28, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herasimenka, A.; Bright, J.; Knuutila, A.; Howard, P.N. Misinformation and professional news on largely unmoderated platforms: The case of telegram. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | # | Country | # |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1 | Russia | 10 |

| 2018 | 5 | Iran | 6 |

| 2019 | 4 | Spain | 4 |

| 2020 | 17 | Indonesia | 3 |

| 2021 | 15 | Switzerland | 2 |

| Nigeria | 2 | ||

| The Netherlands | 2 | ||

| Italy | 2 |

| Medium | Start | Subscribers | Posts | S/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT en español | 16 August 2016 | 110,772 | 24,128 | 4.59 |

| eldiario.es | 25 September 2015 | 45,795 | 7152 | 6.4 |

| laSexta | 14 April 2020 | 27,120 | 1792 | 15.13 |

| euskalnews.com | 25 April 2020 | 23,873 | 5671 | 4.21 |

| CNN en Español | 1 July 2016 | 21,167 | 3058 | 6.92 |

| Público | 28 July 2016 | 16,244 | 6573 | 2.47 |

| elnacionalcat | 25 January 2017 | 15,808 | 17,897 | 0.88 |

| Antena 3 Noticias | 25 May 2020 | 11,400 | 3068 | 3.72 |

| El Mundo | 11 April 2016 | 10,986 | 3229 | 3.4 |

| EL PAÍS | 22 June 2016 | 10,782 | 3162 | 3.41 |

| Libertad Digital Oficial | 26 February 2019 | 7459 | 583 | 12.79 |

| Diario MARCA | 21 August 2019 | 4157 | 79,033 | 0.05 |

| COPE | 14 July 2020 | 4115 | 3153 | 1.31 |

| Europa Press | 3 February 2021 | 4057 | 781 | 5.19 |

| 20 minutos | 5 August 2018 | 2314 | 137,471 | 0.02 |

| El Huffpost | 18 April 2016 | 2177 | 794 | 2.74 |

| Granada Hoy | 30 October 2020 | 2150 | 580 | 3.71 |

| El Confidencial | 12 April 2018 | 1988 | 42,473 | 0.05 |

| Diario AS | 20 August 2019 | 1980 | 109,124 | 0.02 |

| OK Diario™ | 11 November 2020 | 1610 | 756 | 2.13 |

| La Voz de Galicia | 22 May 2020 | 1161 | 54,689 | 0.02 |

| Vozpópuli | 29 March 2021 | 866 | 297 | 2.92 |

| Euronews Spain | 6 January 2016 | 609 | 44,183 | 0.01 |

| La razón | 9 July 2020 | 313 | 9421 | 0.03 |

| Esdiario.com | 7 July 2020 | 255 | 821 | 0.31 |

| Cadena SER Jaén | 22 February 2021 | 202 | 246 | 0.82 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrero-Solana, V.; Castro-Castro, C. Telegram Channels and Bots: A Ranking of Media Outlets Based in Spain. Societies 2022, 12, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060164

Herrero-Solana V, Castro-Castro C. Telegram Channels and Bots: A Ranking of Media Outlets Based in Spain. Societies. 2022; 12(6):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060164

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrero-Solana, Victor, and Carlos Castro-Castro. 2022. "Telegram Channels and Bots: A Ranking of Media Outlets Based in Spain" Societies 12, no. 6: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060164

APA StyleHerrero-Solana, V., & Castro-Castro, C. (2022). Telegram Channels and Bots: A Ranking of Media Outlets Based in Spain. Societies, 12(6), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060164