Hotel Naming in Russian Cities: An Imprint of Foreign Cultures and Languages between Europe and Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

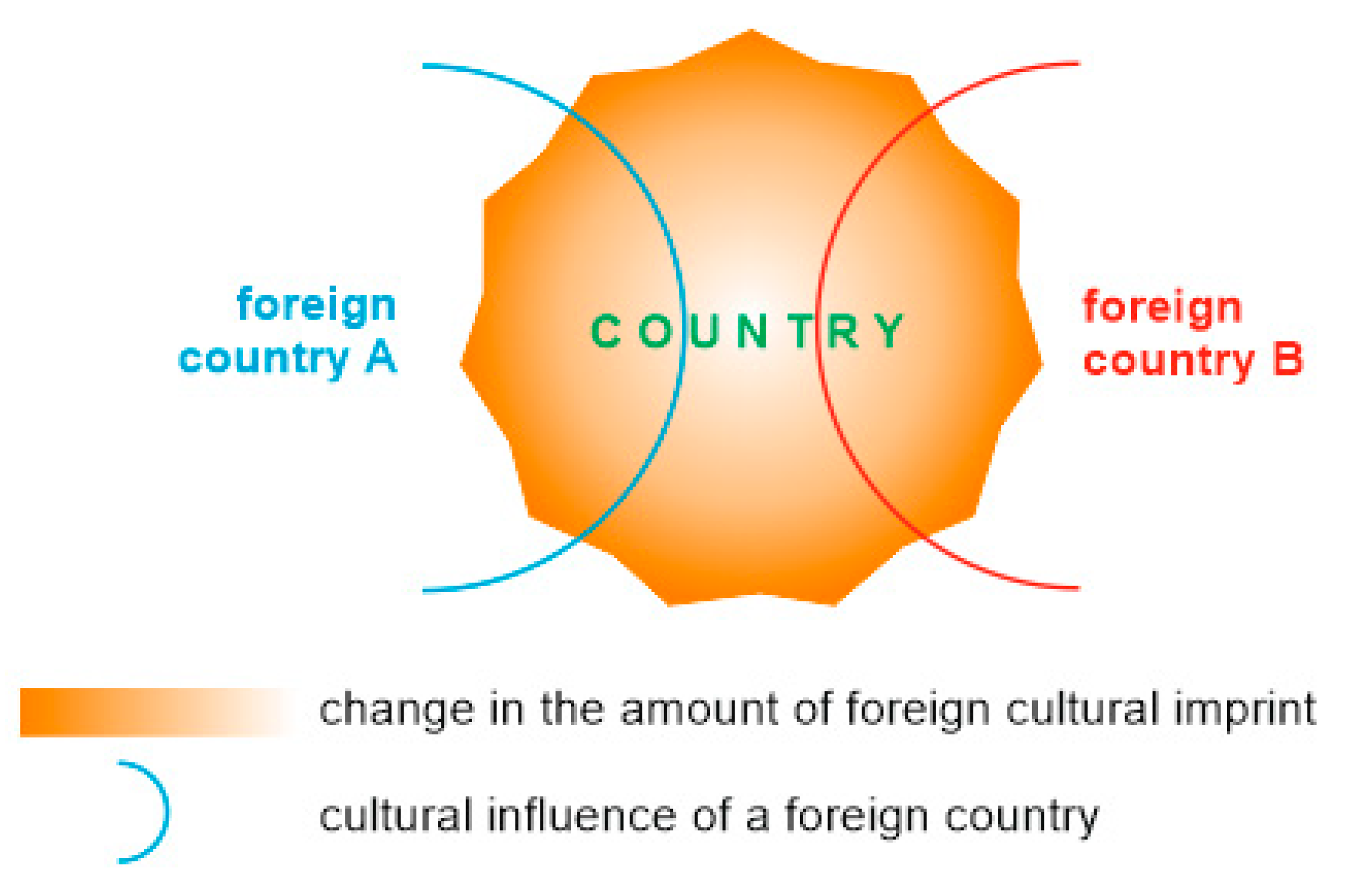

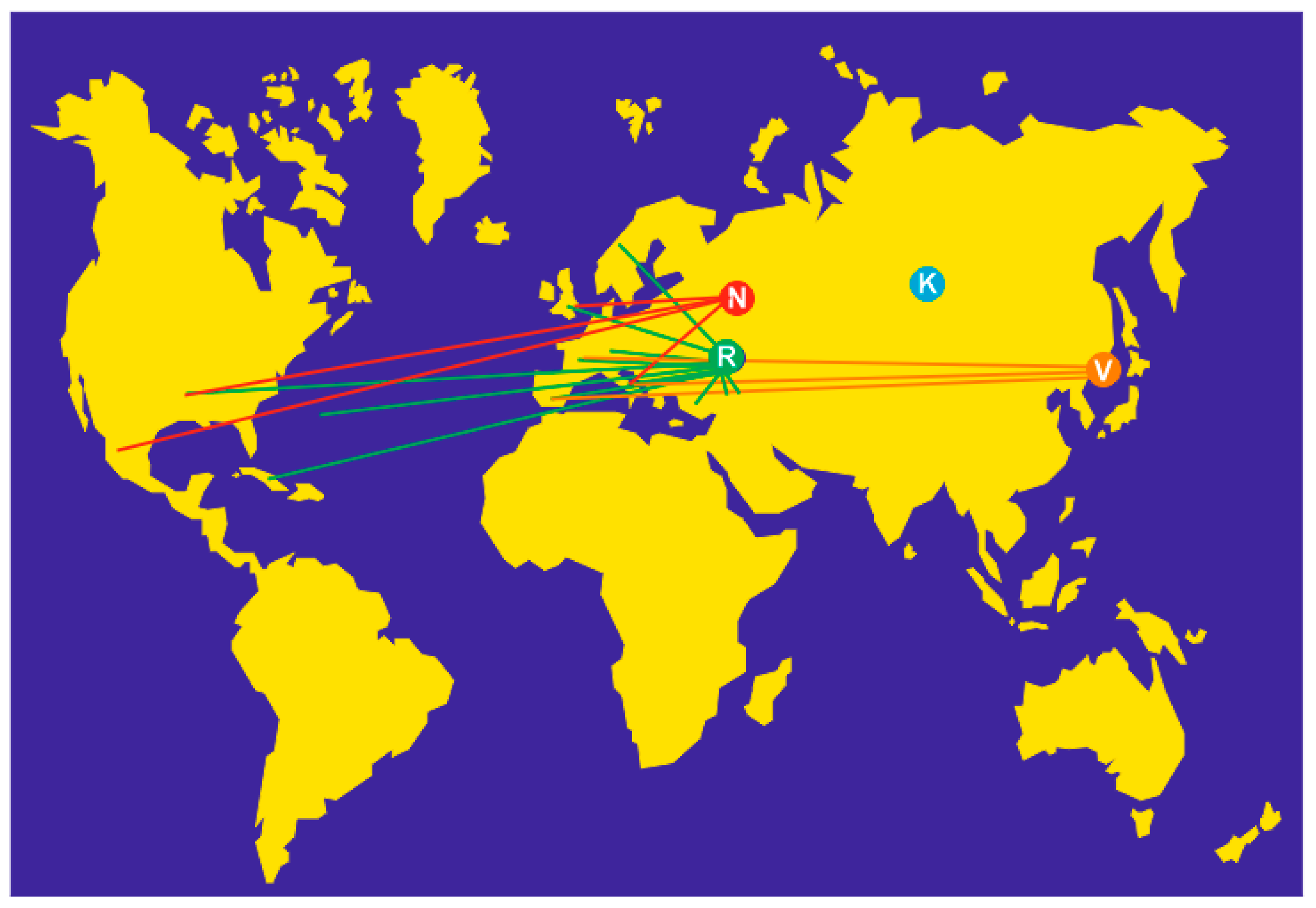

2. Conceptual Remarks

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The number of the hotel names representing foreign cultures and languages is significant in the selected cities, which indicates the involvement of the cultural exchange with the outside.

- (2)

- The position of the cities on the geographical periphery of Russia or in its “core” does not determine the foreign imprint in the hotel names (thus, the central hypothesis is not confirmed).

- (3)

- The majority of the hotel names with foreign elements demonstrate affinity to the West European cultures and languages, and, apparently, only the distance from the western border of Russia may affect the studied imprint.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bharwani, S.; Butt, N. Challenges for the global hospitality industry: An HR perspective. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2012, 4, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhaes, C. Borders, Globalization and Eucharistic Hospitality. Dialog 2006, 49, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwigol-Barosz, M.; Rohoza, M.; Pashko, D.; Metelenko, N.; Loiko, D. Assessment of international competitiveness of entrepreneurship in hospitality business in globalization processes. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Go, F. Tourism and Hospitality Management: New Horizons. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1990, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, F.M. A conceptual framework for managing global tourism and hospitality marketing. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1996, 21, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Cordos, M. Human resources in hospitality industry from globalisation perspective. Qual. Access Success 2012, 13, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, J.M. Executive insights on globalization: Implications for hospitality managers in emerging locations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.D. Macroforces driving change into the new millennium—Major challenges for the hospitality professional. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 18, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D. Globalization practices within the U.S. Meetings, Incentives, Conventions, and Exhibitions industry. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2016, 17, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C. Trends in hospitality management research: A personal reflection. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (World Tourism Organization). International Tourism Highlights; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Avdeyeva, O.A.; Baranova, A.V.; Okunyev, D.O. Factors affecting international trade in tourism services in Russia. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 91071. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.K.W.; Tsui, W.H.K. Cross-border tourism: Case study of inbound Russian visitor arrivals to China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhandzhugazova, E.A.; Blinova, E.A.; Orlova, L.N.; Romanova, M.M. Development of red tourism in the perspective of the Russian-Chinese economic cooperation. Espacios 2018, 39, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, D.A. Current state and prospects of Russian outbound tourism. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2018, 9, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pshenichnykh, Y.; Yakimenko, M.; Zhertovskaja, E. Checking convergence hypothesis of the Russia tourist market. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 26, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudina, T.A.; Samsonenko, T.A.; Grigoryan, T.A.; Eremina, E.A.; Karamova, A.S. The Concept of Russia’s Becoming a Growth Pole of the Global Tourism: Pros and Cons. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2020, 73, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, E.V.; Ryabova, T.M.; Kabanova, E.E.; Rogach, O.V.; Vetrova, E.A. Domestic tourism in Russian Federation: Population estimations, resources and development constraints. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2017, 8, 436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir, I.B.; Ivushkina, E.B.; Morozova, N.I.; Samodelov, A.N. The Resource Constraints of the Tourism Industry Growth in Russia. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2020, 73, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sheresheva, M.Y. The Russian tourism and hospitality market: New challenges and destinations. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedusenko, E.A. Hospitality investment environment in Russia. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2017, 8, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Morozova, I.A.; Volkov, S.K.; Avdeyuk, O.A. Development trend of Russia’s tourism and hospitality sector. Actual Probl. Econ. 2014, 159, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Romanyuk, A.V.; Gareev, R.R. Hospitality industry in Russia: Key problems and solutions. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 788–800. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, J. May I have your name please? Norfolk Island hotel names. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chimenson, D.; Tung, R.L.; Panibratov, A.; Fang, T. The paradox and change of Russian cultural values? Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Branding Hotel Portfolios. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1992, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H. How to develop a strong hotel branding strategy with a weak branding budget. J. Vacat. Mark. 1995, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, V.; Surucu, E.; Tuzunkan, D.; Toanoglou, M. The relationship between income and branding: A case study at five star hotels in Turkey. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 629–639. [Google Scholar]

- Dioko, L.D.A.N.; So, S.I.A. Branding destinations versus branding hotels in a gaming destination-Examining the nature and significance of co-branding effects in the case study of Macao. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cai, L.A. Chinese Hotel Branding: An Emerging Research Agenda. J. China Tour. Res. 2014, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.W.; Mattila, A.S. Hotel Branding Strategy: Its Relationship to Guest Satisfaction and Room Revenue. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Yang, J.; Yang, C.-E. Hotel internal branding: A participatory action study with a case hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Scharl, A. An investigation of global versus local online branding. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therkelsen, A.; Gram, M. Branding Europe—Between nations, regions and continents. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G. Hijacking culture: The disconnection between place culture and place brands. Town Plan. Rev. 2015, 86, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, C.G.; Du Plessis, T. Beyond the Branding Iron: Cattle Brands as Heritage Place Names in the State of Montana. Names 2016, 64, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Gupta, S.; Kitchen, P.; Foroudi, M.M.; Nguyen, B. A framework of place branding, place image, and place reputation: Antecedents and moderators. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Chan, A.K.K. The role of language and culture in marketing communication a study of Chinese brand names. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 2005, 15, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X. Linguistic and cultural characteristics of domain names of the top fifty most-visited websites in the US and China: Across-linguistic study of domain names and e-branding. Names 2012, 60, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, M. Semiotizing a product into a brand. Soc. Semiot. 2013, 23, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivkovic, D. Towards a semiotics of multilingualism. Semiotica 2015, 207, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gursoy, D.; Deng, Z.; Gao, J. Impact of culture on perceptions of landscape names. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.B.; Quelch, J.A.; Taylor, E.L. How global brands complete. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sujatna, E.T.S.; Pamungkas, K.; Heriyanto. Names as branding on nature tourism destinations in Pangandaran, Jawa Barat-Indonesia: A linguistic perspective. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 27, 803–814. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, P. Organizational form as a solution to the problem of credible commitment: The evolution of naming strategies among U.S. hotel chains, 1896-1980. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.H.; Murphy, J. Branding on the web: Evolving domain name usage among Malaysian hotels. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Kang, J.; Sumarjan, N.; Tang, L. The Incorporation of Consumer Experience into the Branding Process: An Investigation of Name-Brand Hotels. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoamo, M. More thoughts on core-periphery and tourism: Brexit and the UK Overseas Territories. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F. Dynamics of core and periphery in tourism: Changing yet staying the same! Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, C.; Yu, C.-P.S.; Cole, S.T. Exploring quality of life perceptions in rural midwestern (USA) communities: An application of the core-periphery concept in a tourism development context. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. The core-periphery structure of internationalization network in the tourism sector. J. China Tour. Res. 2011, 7, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, J.; You, H.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Core-periphery spatial structure and its evolution of tourism region in Sichuan Province. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2007, 62, 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Gormsen, E. The impact of tourism on coastal areas. GeoJournal 1997, 42, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Konrad, V. In the space between exception and integration: The Kokang borderlands on the periphery of China and Myanmar. Geopolitics 2018, 23, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, D. Cosmopolitanism’s sociology and sociology’s cosmopolitanism: Retelling the history of cosmopolitan theory from stoicism to Durkheim and beyond. Distinktion 2014, 15, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanty, G. The cosmopolitan imagination: Critical cosmopolitanism and social theory. Br. J. Sociol. 2006, 57, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, E.; Harris, N. From sociology to social theory: Critical cosmopolitanism, modernity, and post-universalism. Int. Sociol. 2020, 35, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J. Pictures at an exhibition: Science, patriotism, and civil society in imperial Russia. Slav. Rev. 2008, 67, 934–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaidenko, N.A. The ideas of patriotism in the history of Russian pedagogy. Russ. Educ. Soc. 2013, 55, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, Y.G.; Kolesnikova, E.Y.; Aslanov, Y.A.; Vagina, V.O. Civic patriotism among young sportsman in the South of Russia: Sociological analysis and diagnostics. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2021, 16, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Wickström, D.-E.; Steinholt, Y.B. Visions of the (Holy) Motherland in Contemporary Russian Popular Music: Nostalgia, Patriotism, Religion and Russkii Rok. Pop. Music. Soc. 2009, 32, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A.; Latushko, N.A. Cultivating patriotism—a pioneering note on a Russian dimension of corporate ethics management. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, A.L. Culture as a basis of contemporary Russian ideology: Challenges and prospects. RUDN J. Sociol. 2017, 17, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Argenbright, R. Moscow on the rise: From primate city to megaregion. Geogr. Rev. 2013, 103, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlapentokh, V. Russia’s openness to the world: The unpredicted consequences of the country’s liberalization. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2012, 45, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arel, M.S. Hospitality at the hands of the muscovite tsar: The welcoming of foreign envoys in early modern Russia. Court. Hist. 2016, 21, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikanova, O. In search of a cultural code 5th contribution to the forum about the Firebird and the Fox: Russian culture under Tsars and Bolsheviks by Jeffrey Brooks. Russ. Hist. 2021, 47, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druzhinin, A. The Sea Factor in the Spatial and Socio-Economic Dynamics of Today’s Russia. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druzhinin, A.G. Russia in Modern Eurasia: The Vision of a Russian Geographer. Quaest. Geogr. 2016, 35, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lukin, A.; Novikov, D. Sino-Russian rapprochement and Greater Eurasia: From geopolitical pole to international society? J. Eurasian Stud. 2021, 12, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Barreto, J.; Rubio, N.; Campo, S. Destination brand authenticity: What an experiential simulacrum! A multigroup analysis of its antecedents and outcomes through official online platforms. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazariadli, S.; Morais, D.B.; Barbieri, C.; Smith, J.W. Does perception of authenticity attract visitors to agricultural settings? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, quality, and loyalty: Local food and sustainable tourism experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Macroregion | Location | City Population, mln. | Number of Persons Accommodated (2017), mln. * | Number of CAFs in the Region (2017) * | Number of Hotels in the City (2019) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostov-on-Don | Russian South | Periphery (Europe) | 1.13 | 1.09 | 568 | 153 |

| Nizhniy Novgorod | Russian Centre | “Core” (Europe) | 1.25 | 1.07 | 486 | 109 |

| Krasnoyarsk | Siberia | “Core” (Central Asia) | 1.10 | 0.70 | 369 | 52 |

| Vladivostok | Far East | Periphery (East Asia) | 0.60 | 1.06 | 465 | 81 |

| City | Number of Names with Foreign-Culture Elements | Number of Names with Foreign-Language Elements | R, %% | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostov-on-Don | 14 | 22 | 23.5 | 0.64 |

| Nizhniy Novgorod | 5 | 19 | 22.0 | 0.26 |

| Krasnoyarsk | 0 | 7 | 13.5 | 0.00 |

| Vladivostok | 4 | 16 | 25.0 | 0.25 |

| Country | Rostov-on-Don | Nizhniy Novgorod | Krasnoyarsk | Vladivostok |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 1 | |||

| Austria | 1 | |||

| Bermuda * | 1 | |||

| Cuba | 1 | |||

| France | 2 | 2 | ||

| Georgia | 1 | |||

| Italy | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mexico | 1 | |||

| Norway | 1 | |||

| Spain | 2 | 1 | ||

| Turkey | 1 | |||

| UK | 1 | 1 | ||

| USA | 1 | 2 |

| Language | Rostov-on-Don | Nizhniy Novgorod | Krasnoyarsk | Vladivostok |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | 2 | |||

| English | 10 | 16 | 6 | 13 |

| French | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Italian | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Spanish | 1 |

| Linguistic-Cultural Types * | Rostov-on-Don | Nizhniy Novgorod | Krasnoyarsk | Vladivostok |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-motivated | 9 | 7 | 0 | 6 |

| Direct nomination (indication on organization type) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Indirect nomination: reference to hotel services and functions | 4 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Indirect nomination: reference to construction type | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Indirect nomination: toponyms and famous places | 10 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Symbolic nomination: landscape | 3 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Precedent nomination: real persons | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Precedent nomination: fictional (literature and movie) persons | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kormazina, O.P.; Ruban, D.A.; Yashalova, N.N. Hotel Naming in Russian Cities: An Imprint of Foreign Cultures and Languages between Europe and Asia. Societies 2022, 12, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12020058

Kormazina OP, Ruban DA, Yashalova NN. Hotel Naming in Russian Cities: An Imprint of Foreign Cultures and Languages between Europe and Asia. Societies. 2022; 12(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleKormazina, Olga P., Dmitry A. Ruban, and Natalia N. Yashalova. 2022. "Hotel Naming in Russian Cities: An Imprint of Foreign Cultures and Languages between Europe and Asia" Societies 12, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12020058

APA StyleKormazina, O. P., Ruban, D. A., & Yashalova, N. N. (2022). Hotel Naming in Russian Cities: An Imprint of Foreign Cultures and Languages between Europe and Asia. Societies, 12(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12020058