Abstract

Online reviews have become a fundamental element in searching for and buying a tourism service. In particular, in the phase of post-pandemic caused by the COVID-19, social media are important channels of inspiration of dreams and encouragement to begin envisioning future trips. However, the growing trend of fake reviews is becoming a big issue for consumers. This study proposes and empirically validates a new model that enables predicting consumers’ Credibility Perception of Online Reviews (CPOR) related to tourism, considering all integrated factors of the communication process. A survey was carried out via a structured questionnaire. In particular, 615 answers from Italian travel groups were collected, and correlation and regression analyses were conducted. Results show that the website brand, advisor’s expertise, reviews’ sidedness and consistency, and consumer experience are significant predictors of CPOR. Website usability and reputation are instead weak predictors. This study provides the design and test of a credibility model, contributing to the theoretical and empirical advancement of the literature and enhancing the knowledge on consumer behavior.

1. Introduction

The last two years (2020 and 2021) have been very problematic for the tourism sector; indeed, the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has produced a strong slowdown for travel and the entire tourism industry in Italy and around the world. The difficulties experienced by the sector have also represented a great engine of change and digital innovation in tourism, bringing out new trends in the tourism sector. Digitization of travel agencies and tour operators is one of the first recovery trends, changing how consumers and sellers interact in the marketplace. Old models of word-of-mouth marketing based on one-to-one relationships changed toward a model based on one-to-many amplification of key brand messages, information, and reviews from customers [1]. Crowdsourced reviews enable consumers to collect information concerning products and services they intend to purchase. In particular, with the exponential growth of social media use, people’s behaviours are increasingly influenced by other consumers’ opinions and suggestions, mainly in the case of purchasing decisions [2,3,4]; therefore, the online reviews’ persuasiveness, connected with credibility, is crucial. These concepts also characterize the online travel communities, as consumers usually share their travel experiences and search for information and suggestions from other travellers [5,6,7]. A Google search also confirms this trend: during May 2021; indeed, online travel and accommodation searches grew on average by +200% compared to 2020 [8].

In this context, it will be essential for travel agencies, tour operators, accommodation facilities and operators in the tourism sector to improve their presence online and on social media.

Amazon, TripAdvisor, and Yelp deeply base their visibility on consumers’ online reviews. However, crowdsourced online reviews sometimes may not be truthful, as the information they share is inaccurate or fraudulent; moreover, they sometimes have been written by individuals (not consumers) who might overrate or underrate a product or service for different reasons [9,10,11]. For example, positive reviews could be written either by the owners themselves or by paid consumers to increase their ranking. Other companies could write negative reviews to put the competitors in a bad light or by consumers inexperienced in writing reviews or travelling could share opinions leading to irrelevant and misleading aspects.

Therefore, this post-COVID-19 pandemic period characterized by a slow recovery of the tourism market, the credibility and trustworthiness of online reviews are very relevant concepts for all operators in the tourism sector. Therefore, there is a need to identify and analyse factors influencing CPOR and develop a model to explain consumer behaviour. The study aims to understand which variables affect CPOR, the correlations among the different variables, and how consumer attitudes act in a credibility process.

The remainder of the paper consists of four sections. Section 2 describes the related works about online review credibility and introduces the study’s hypotheses. Section 3 describes the used methodology. Section 4 discusses the testing findings related to the proposed hypotheses and describes the CONCEPT model. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

Most previous research studies concerning online travel reviews and their credibility, focused mainly on the characteristics of online review messages and structure [12,13,14,15] and the message source [14,16,17,18,19]. However, the relevant literature mainly looks at these factors as isolated and stand-alone perspectives; to our knowledge, no research in the tourism field has provided a unified view of factors affecting CPOR. Aiming to address this gap, this study borrows some concepts from the model of communication of Shannon and Weaver [20], examines the interaction of four different factors—source, message, channel, and receiver—and develops a model that includes these factors in an integrated way to analyse which have a greater influence on CPOR.

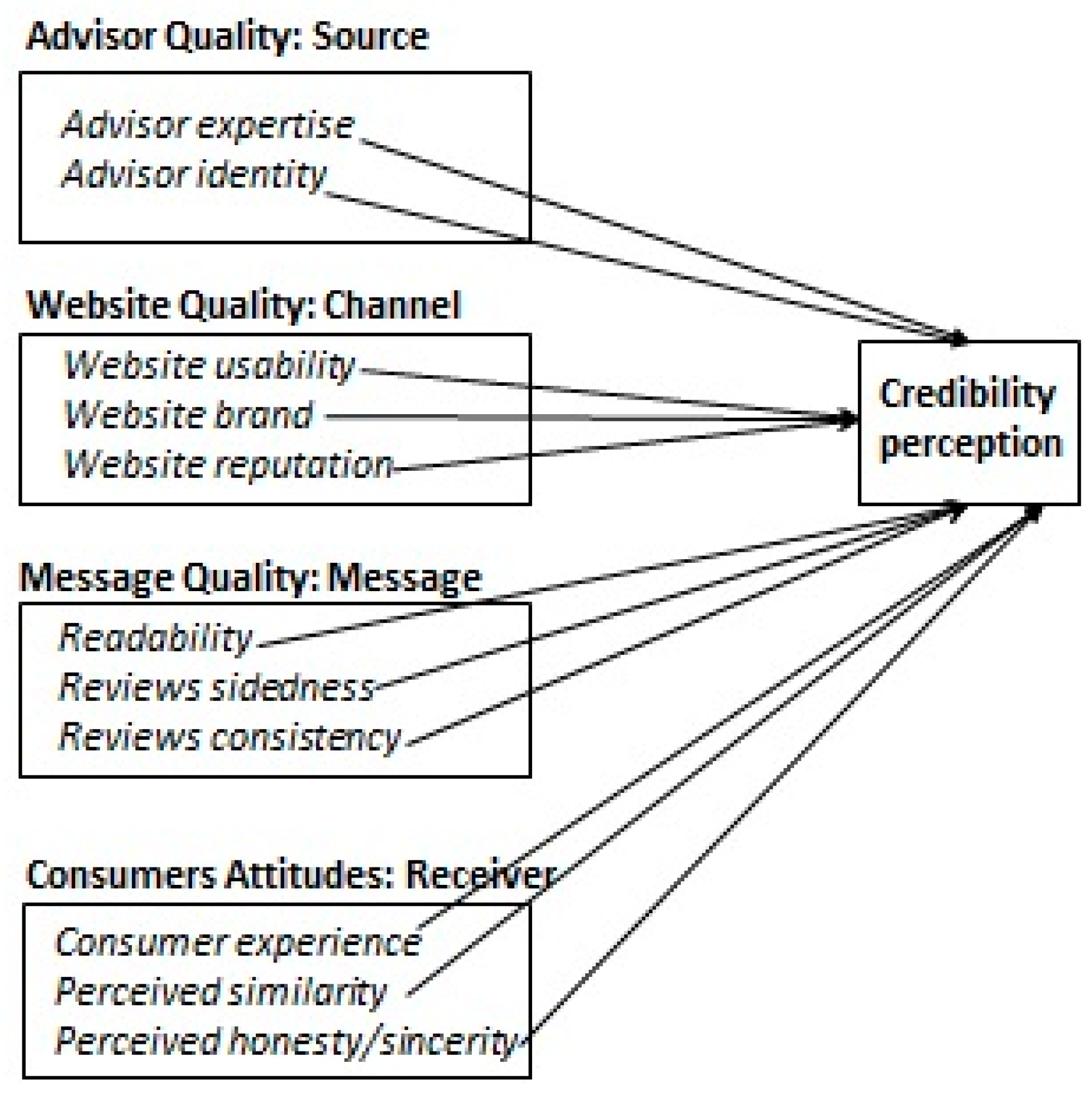

Other important theoretical frameworks have been used in literature to analyse online reviews such as: the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). For example, TAM has been used to analyse age and gender differences in user-generated content (UGC) and online reviews adoption intention [21]. This study found that the strongest determinants are: perceived usefulness for males, perceived ease of use for females and older travellers, and expertise for younger travellers [21]. An example of use of TPB was given with the aim to analyse the impact of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) on a tourism destination choice. Results indicated that eWOM has a significant and positive impact on attitudes toward visiting a destination, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and intention to travel [22]. Unlike these studies, our model takes into account other determinants more related to the communication process and analysed the interaction of variables related to factors such as source, message, channel, and receiver. This study, in fact, takes into account not only factors related to the message (readability, review sidedness, and review consistency) and source (advisor expertise and advisor’s identity), but also other factors of the credibility process related to the channel; in other words, the website’s usability, brand, and reputation, as well as the receiver (consumer), considering the mediating role of the consumers’ attitudes. These attitudes are perceived honesty and sincerity of the advisor, perceived similarity to the advisor, and consumer experience.

Credibility is defined as the believability of information and its source [23]. It is a fundamental element in the persuasion process and depends on the authoritativeness of the source, the structure of the message, how the content is conveyed, and media perceptions [24]. In the tourism field, credibility has a fundamental role for consumers who otherwise cannot evaluate a destination or service before purchase due to the intangible nature of tourism products [25]. Ayeh et al. [26] found the central mediating role of attitude and homophily as a determinant of credibility toward consumer-generated content. Some studies [27,28] are oriented to underline that online information is more credible than information from other more traditional media because experienced travellers post the information, and they are judged to be credible sources. A different point of view is given in studies [29,30,31] underlining that any individual can post online information that cannot be verified each time; therefore, it is less credible than information coming from other sources [29,30,31]. According to different authors, the most relevant credibility factors are trustworthiness, expertise, and advisor credibility [18,32]. Other authors have analysed in particular the contents of reviews and the characteristics of reviewers. For example, the review content has been judged by its readability, i.e., the text understandability by the readers [15]. Manganari and Dimara [33] underlined the positive role of emoticons in online consumers’ reviews. Kusumasondjaja et al. [17] found that the perception of credibility is determined by the identity of the reviewer and the value of the review. Similarly, Xie et al. [19] found that hotel reviews perceived as most credible were those that made the reviewer’s identity clear. Cheung et al. [12] found instead that the credibility of online reviews is affected mainly by argument quality followed by the source credibility and review consistency.

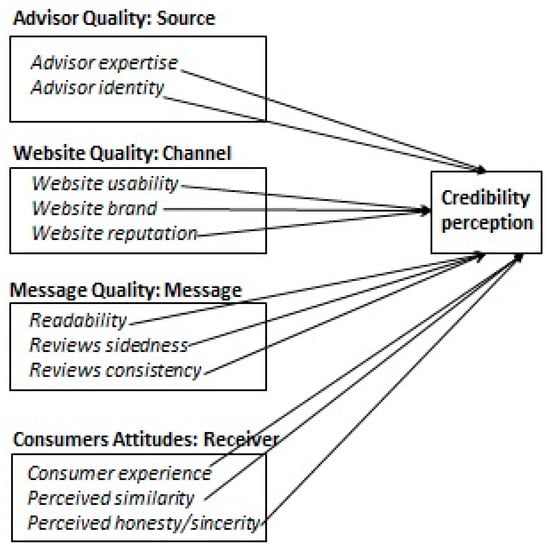

In the following sections, the different constructs considered are analysed in detail through a literature review, and a model that systemizes them is introduced and empirically tested. The model has been represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONCEPT model. (All relationships illustrated in the figure are positive).

2.1. Website Quality

Website quality is an important construct to consider in the CPOR process; in fact, customers’ perception of a website affects their intentions to purchase while on it [34]. In particular, the variables to be considered for this construct are website usability, brand, and reputation.

Usability is defined as “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use”, according to ISO 9241 [35]. Web usability was defined as the ability of web applications to support user experience by providing an efficient system in functionality and navigation with minimum effort [36].

Users are not inclined to use websites that are difficult to navigate [36]. Different studies [35,36,37,38,39,40] analysed the relationship between the usability of websites and user’s trust, and how usability affects consumers’ credibility.

Website brand (the quality by which the website is communicated and marketed) increases perceived trust and helps maintain long-term customer relationships on the Internet [41]. It has two characteristics: awareness and image. Website awareness is the customers’ awareness produced by a website, customers who think that a well-known website is more likely to satisfy their needs. Website image is defined as the “perceptions about a website name as reflected by the website associations held in customer memory” [34].

Another important related variable is the website reputation (the quality of inspiring trustworthiness). A website with a good reputation meets customers’ expectations and can satisfy their needs and increase their trust [42]. Website brand and reputation, indeed, have a significant impact on consumers’ trust and their purchase intentions [43,44]. According to Chang et al. [45], when a consumer intends to book a hotel online, if the quality and brand of the website are perceived to be high, consumers will have a high level of trust, resulting in a propensity to buy from it. Therefore:

Hypothesis H1.

Website usability has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H2.

Website brand has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H3.

Website reputation has a positive effect on CPOR.

2.2. Advisor Quality

Advisor quality is another construct that affects online information credibility and two important variables of this construct are advisor expertise and identity.

The expertise of a reviewer is related to its ability to provide correct information; reviewers’ expertise usually contributes to improving people’s trust [46]. This capability can be technical (a specialized knowledge for writing comments on a given product) or practical (e.g., the reviewer is someone that directly used a product and/or a service) [47]. Additionally, the number of reviews concerning a service, or a product may influence the consumer’s decision [16]. Moreover, reviews can be written either by experts able to critically assess a product/service or by laypersons. Different factors can influence the writing of a review. Sometimes companies pay reviewers asking them for positive or negative reviews; in other situations, reviewers can be influenced by other reviewers’ opinions (herd effect) [48]. To overcome this issue, some online marketplaces enable consumers to see profile information on advisors so that they can judge their credibility [28,49]. When the availability of personal information is limited, consumers have difficulty in identifying whether an advisor is an expert or not. Kusumasondjaja et al. [17] observed that if the reviewer’s identity is known, negative online reviews are perceived as more credible than positive reviews, if the reviewer’s identity is unknown there are no significant differences. Accordingly:

Hypothesis H4.

Advisor expertise has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H5.

Advisor identity has a positive effect on CPOR.

2.3. Message Quality

Message quality is characterized by usefulness, accuracy, and importance of the information contained in the message [50]. Quality is a crucial issue for credibility of online information, and for stimulating consumers to make effective decisions on purchases. Gobinath and Gupta [51] observed that if information overload or the information quality is below the average, the consumer’s decision effectiveness decreases. According to Thomas et al. [52], information accuracy significantly affects review credibility. Quality is therefore crucial for effective consumers’ decisions. The review’s readability, sidedness, and consistency are three important variables of the message quality construct.

Readability is the degree of understandability of a text to readers, based on the text syntactical elements and style. According to Grifoni et al. [10], the higher the readability of a review, the more credible it is perceived. Understanding is an essential factor that affects CPOR.

Review sidedness indicates whether a review is one-sided (i.e., containing only negative or only positive reviews) or two-sided (i.e., containing both positive and negative comments). A two-sided message is generally perceived as more believable than a one-sided one [53].

Finally, review consistency indicates how much information in a review is consistent with other reviews. Information consistency is a heuristic cue that affects knowledge adoption in the online community [54]. According to Cheung et al. [12], “individuals heuristically assess a message by comparing that message with other similar messages, and information that many reviewers consistently present is likely to be perceived as being more believable.” We then argue that:

Hypothesis H6.

Readability has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H7.

Review sidedness has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H8.

Review consistency has a positive effect on CPOR.

2.4. Consumers’ Attitudes

Attitudes are an essential construct for understanding consumers’ decision-making processes [55]. Variables that affect these attitudes are perceived trustworthiness, that is, the perceived honesty and sincerity of the advisor and the perceived similarity to the advisor’s, and consumer’s experience.

Trustworthiness is the consumer’s confidence of objectivity and honesty of source in providing information [46]. The perception by the consumer of honesty and sincerity of the advisor plays an important role in the credibility process. The review is also perceived as more trustworthy [56,57,58] when consumers perceive advisors have lifestyles and preferences similar to their own.

The consumer experience in reading and evaluating online reviews is another important variable affecting the CPOR process. Judgments of reviewers are subjective, and they can vary according to reviewers’ attitudes. For example, a reviewer with low experience can give high ratings, but the content of the review instead contains an evaluation that is not coherent with the rating value [10]. It is then very important for consumers to know how to evaluate reviews. Consequently, we assume that:

Hypothesis H9.

Perceived honesty and sincerity of the advisor has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H10.

Perceived similarity to the advisor has a positive effect on CPOR.

Hypothesis H11.

Consumer experience has an effect on CPOR.

3. Research Design and Methodology

This study aims to identify factors that influence CPOR and how these factors are related to each other. In particular, it analyses the uses and opinions of Italian consumers in reading online reviews containing information related to a travel, from destination choice to information about a hotel, restaurant or services/attractions of a destination.

Italy was chosen as the survey location because it is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, and tourism is an essential driver for the economy. We survey Italian tourists because almost half of the tourism market in Italy comes from the domestic segment.

In fact, data of National Tourism Agency–ENIT, in 2019 in Italy indicate that there was 218.8 million foreigners’ presences and 215.3 million Italian presences. The Italian presences grew by 1.4% compared to 2018 [59]. In 2020, the health emergency related to the COVID-19 and related measures caused a drastic reduction in both incoming and outgoing tourist flows (the reduction in presences in 2019 for inbound tourism was of 54.6% and for outbound tourism was of 54.1%) [60]. However, the emerging trends in the tourism sector confirm an increase in domestic tourism (increased by 5%). The COVID-19 pandemic led Italians to prefer domestic tourism; among those who went on vacation, 96% remained in Italy, and domestic tourism is increased of 5% [61]. It is foreseen that domestic tourism in Italy will continue to be a key driver of recovery in the short and medium term. Another trend during this phase of recovery of the tourism market is digitalization. According to the Digital Innovation Observatory [62]. In Italy, e-commerce in this field has registered constant growth in recent years. Travellers are increasingly digital and generally use the web and social media before, during, and after a trip. Therefore, the trend of “web 2.0 tourists” is the constant sharing of their travel experiences. Internet is a real form of inspiration for 74% of Italian digital tourists. Around 88% of Italian tourists do search for information for tourism and 82% use digital tools to book before leaving, 45% share their experiences online, 38% write reviews, and 35% have changed their travel plans after reading negative comments online [60]. However, the availability of studies and the understanding of the factors influencing the choices of Italian consumers on e-commerce sites in Italy are limited. Similar research studies that have identified and explored key aspects of online travel reviews that positively and negatively influence consumers’ behaviour have been conducted in other countries.

The study aims to understand which variables affect CPOR, the correlations among the variables, and how consumer attitudes act in the credibility process. Starting from these questions, we assume that there are four main constructs and different related variables that act in the process of CPOR and influence online purchases:

- Source: quality of the advisor (person who writes the reviews), which includes the variables of that person’s expertise and identity;

- Message: message (review) quality, which includes the variables of readability, sidedness, and consistency;

- Channel: quality of the website that provides the information, including the variables of usability, reputation, and brand;

- Receiver: attitudes of the consumer who consults the reviews, which includes the variables of perceived honesty/sincerity of the review, perceived similarity with the advisor, and consumer experience.

A web-based survey has been carried out with an online questionnaire that involved a sample of Italian people different for age, gender, and educational level (as specified in the next section).

The main advantage of a traveller community survey is that the survey is aimed at a community accustomed to using online tools and with a high level of experience on the topic, as experienced by many authors such as Hung and Law [63]. This is a very relevant aspect for CPOR. Moreover, an online methodology allows exporting data collected via the web to a database for elaboration.

A questionnaire was posted on 50 Italian travel groups on Facebook to have a sample of experienced consumers with online reviews.

A convenience sample was used to provide the information necessary to build the model and to verify its validity. The survey is aimed at the general online population of Italy who travels for leisure and plans their travel online.

The questionnaire was structured into two parts, and it consisted of closed dichotomous and multiple-choice questions. The first part collected socio-demographic information; habits in using the Internet, in travelling and reading online reviews; and opinions on social influence and trust in reviews. The second part included structured statements and used a 5-point Likert-type scale; it was used for measuring consumers’ perceptions related to the following constructs: advisor quality (with questions related to experience, anonymity, and number of reviews of the reviewer); message quality (with questions related to readability, sidedness, and consistency of the reviews; website quality (with questions related to usability, brand, and reputation of the website); consumer attitudes (with questions related to the perception of the consumers in reading the reviews (i.e., similarity with the reviewer, honesty, sincerity, etc.). The scale values were 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree nor disagree), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire was pilot tested to verify the validity of its content and the comprehensibility of both the questions and the scale used to make the assessments.

Of the 670 returned questionnaires, 615 were complete and used for statistical latent segmentation analysis. The analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS 2012).

Ethical Considerations

Respondents were provided with an informed consent for the questionnaire that explained the aim of the study, how long it took answering, contact persons for asking any clarification, their voluntary participation, the potential for harm, anonymity, and confidentiality. The questionnaire did not collect any personal or sensitive data and information that would enable the extraction of personal data or data related to respondents.

Data processing was fully compliant with the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural per-sons with regard to the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) and of the GDPR. To qualify for participation, respondents were required to (i) be at least 18 years old, (ii) have used the Internet to read online travel reviews, and (iii) have travelled in the last three years.

4. Study Finding

Of the 615 respondents, a higher proportion comprised women (71% versus 29% men). The questionnaire targeted people aged 18 years and over; significant representation was from those aged 29–39 years (30%) and those aged 40–49 years (29%). The respondents’ level of instruction was medium-high (44% high school graduate and 47% degree), and the majority (65%) was employed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of the respondents.

The following sections show the different constructs and variables analysed.

4.1. Consumer Habits

This section of the questionnaire asked about respondents’ habits in using the Internet and social media and experiences in travelling and reading online. All respondents were experienced both in travelling and in Internet use. Around 52% declared travel on average from 1 to 3 times per year, 34% from 3 to 6 times per year, and the remainder more than 7 times per year. The average time per day spent on the Internet was high. In fact, respondents stated that they usually spend a minimum of less than 1 h per day (10%), to 1–3 h per day (56%), 3–10 h per day (30%), or even 10–20 h per day (4%) on the Internet. As the sample was chosen among users of social travel groups and blogs, respondents claimed skill in reading online reviews, having read online reviews not only every time they take a trip (34%) but also weekly (29%) or every day (19%). Typical daily time spent reading blog posts ranged from 1–3 h (12%) to less than 1 h (27%) and less than 30 min (61%). The platforms mainly used to read online reviews were TripAdvisor, Booking, Google, and Facebook.

4.2. Social Influence

Webster’s dictionary defines influence as “the power or capacity of a person or thing in causing an effect in an indirect or intangible way” [64].

This survey found that usually the first thing that the majority of people claimed to do before travel is to compare their opinions with those of other people. They also search for information and suggestions on social media (blogs, forums, reviews on different platforms).

Most participants stated that online reviews influence them: 21% often, and 62% sometimes change their purchase decisions after reading negative reviews. In general, most respondents (65%) professed sufficient trust in online reviews; another 9% expressed trust “a lot,” 24% “little,” and 1% “nothing.” Of the respondents, 60% claimed to be able to identify fake reviews from real reviews. However, in their travel choices the opinions or suggestions of friends, relatives, and people they value were seen as more important than those of online reviews by strangers on blogs, social networks, or travel communities. This result is confirmed by Hernández-Méndez et al. [7]. In particular, other people’s advice is seen as more important for men than for women.

Regarding experience, 49% of respondents claimed “enough” experience in reading online reviews, 24% “a lot,” and 6% “very experienced.” Strong perceptions were held regarding the issue of fake news: 33% considered this a “very serious” problem, 34% “a lot,” and 24% “enough” (the other respondents considered the problem less serious).

Young people are more open towards online travel reviews, they in fact use a lot of social media and read habitually online review, 50% of respondents in fact consult them every time they take a trip. Moreover, the youth age group 18–28 change their mind often (8%) after reading the reviews compared to the age group 40–49 (3%); however, the youth group is less able to recognize fake reviews and considers this problem less serious than the 29–49 age group.

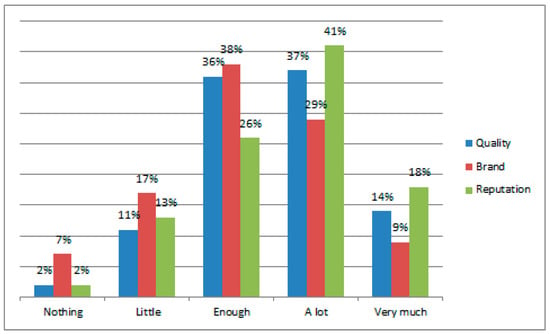

4.3. Consumer Trust

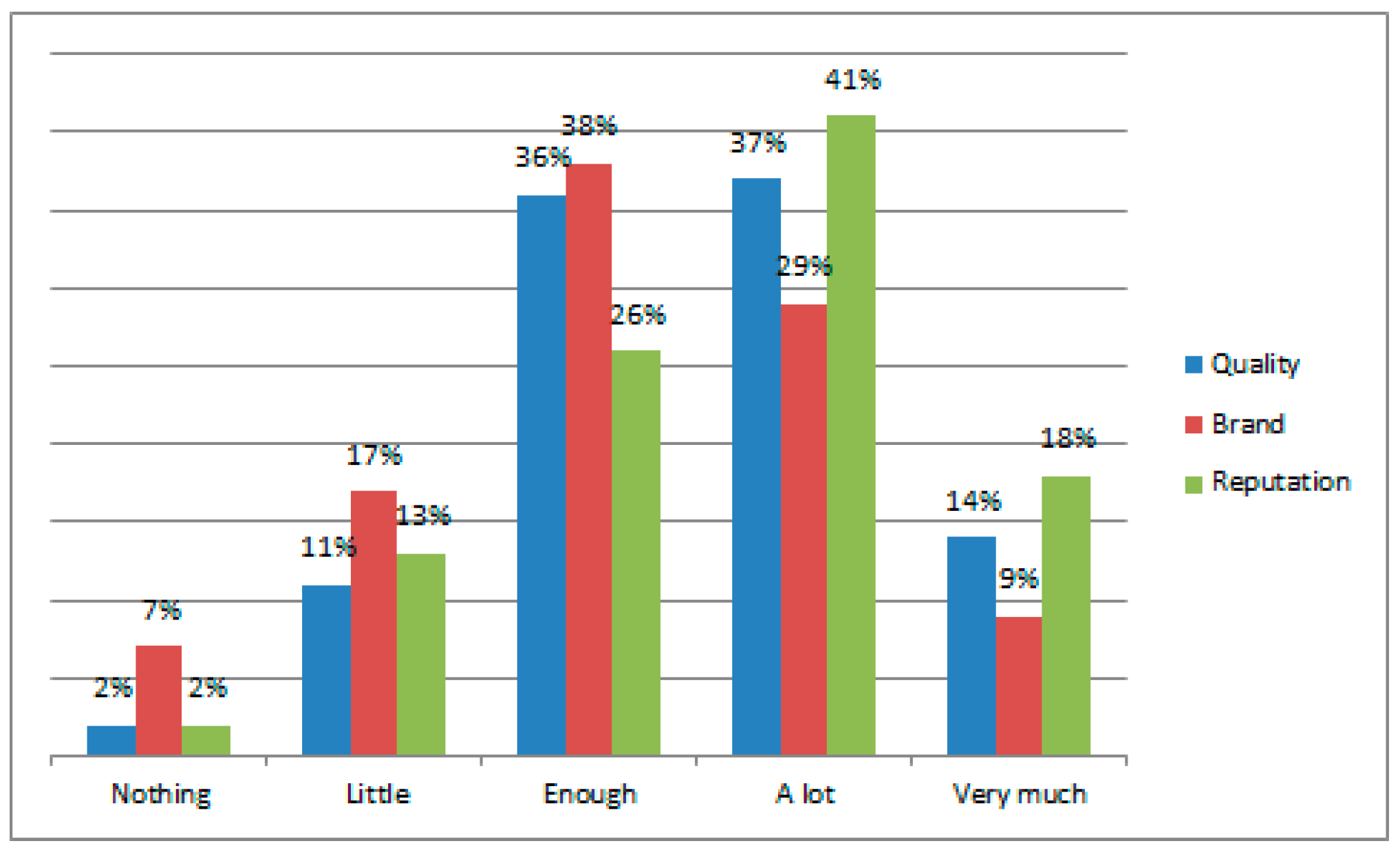

This section of the questionnaire aimed to analyse consumers’ trust related to the four constructs described above: website quality, advisor quality, message quality, and consumer attitudes. The analysis found that concerning the quality construct, the variables that most affected the online trust of reviews by respondents was the reputation of the website (41%), followed by website usability (37%) and brand (29%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Website variables affecting trust of online reviews.

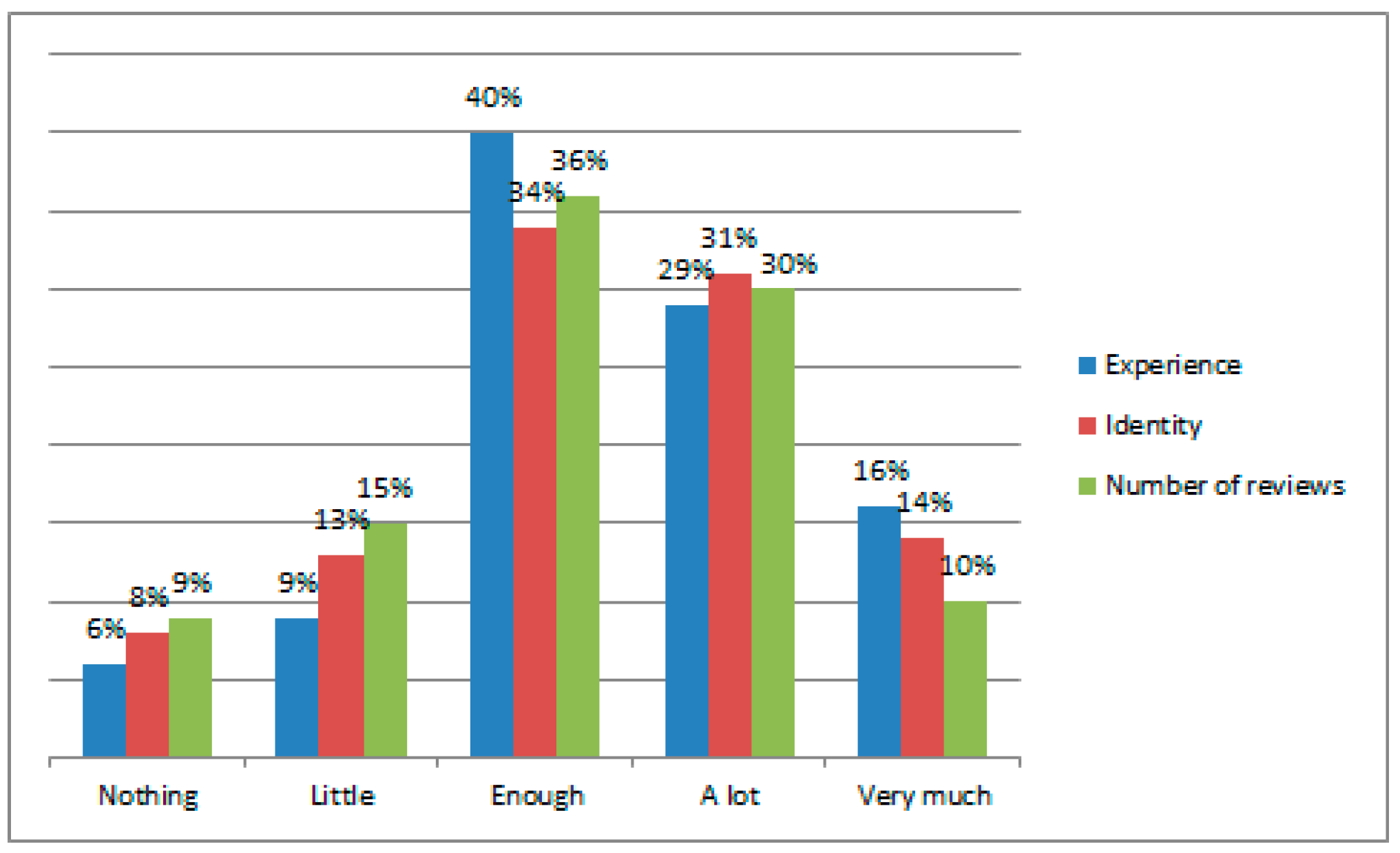

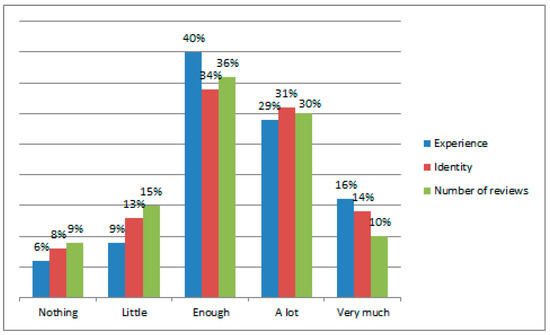

In respect to the advisor quality construct, the identity of the advisor was the variable that most affected trust (31%), although the number of reviews (30%) and the experience of the advisor (29%) were considered important factors in the process of CPOR (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Advisor variables affecting trust of online reviews.

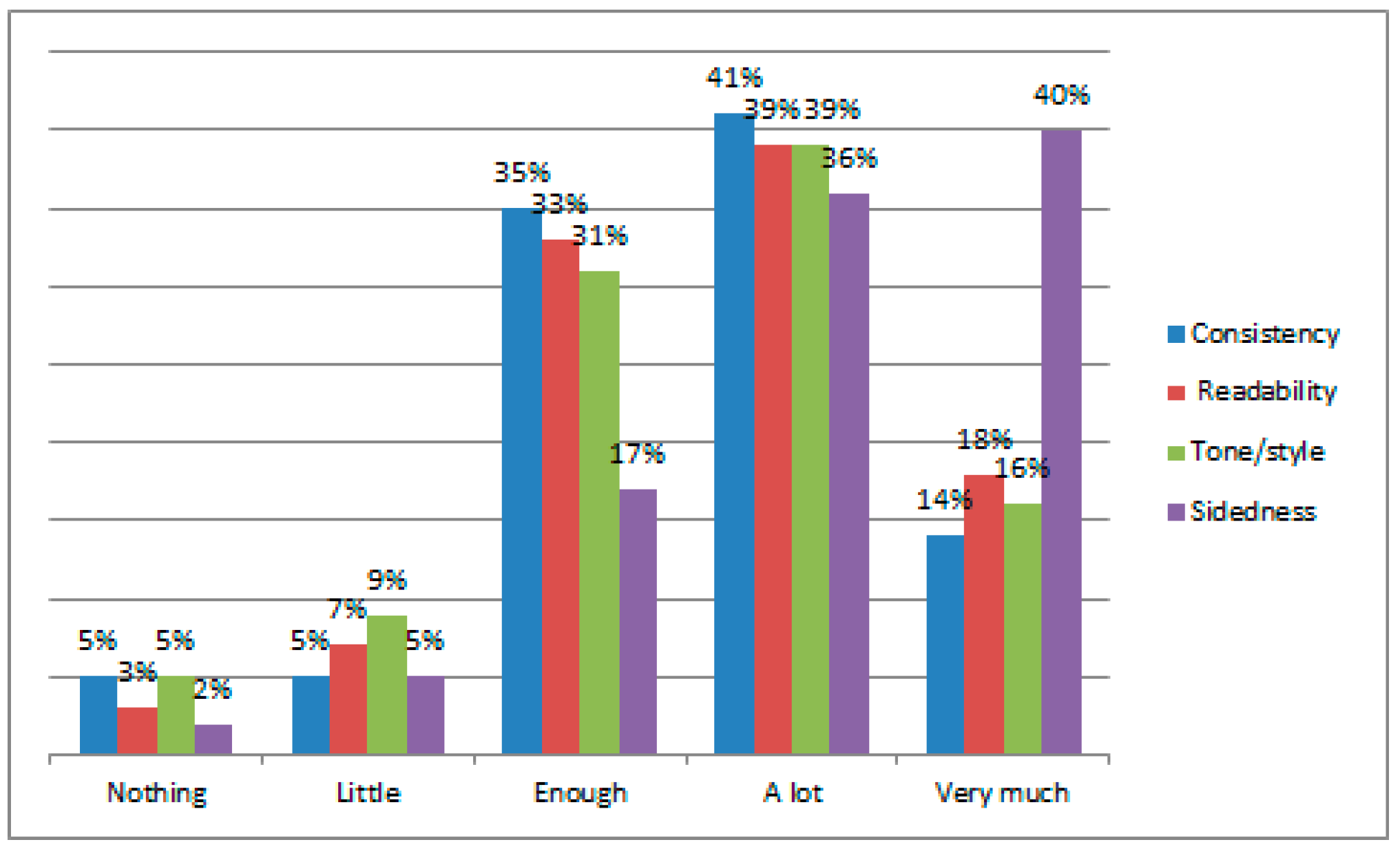

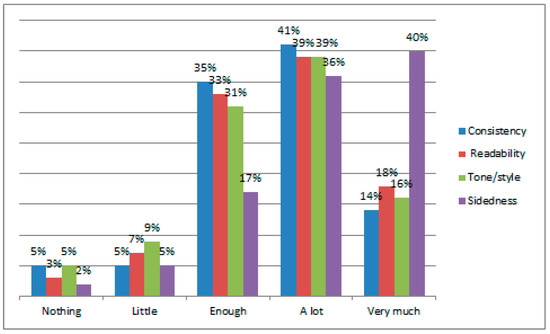

The variables of the message quality construct that most affected trust in online reviews and were perceived as important by respondents were consistency (41%), readability (39%), tone/style (39%), and sidedness (36%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Message variables affecting trust of online reviews.

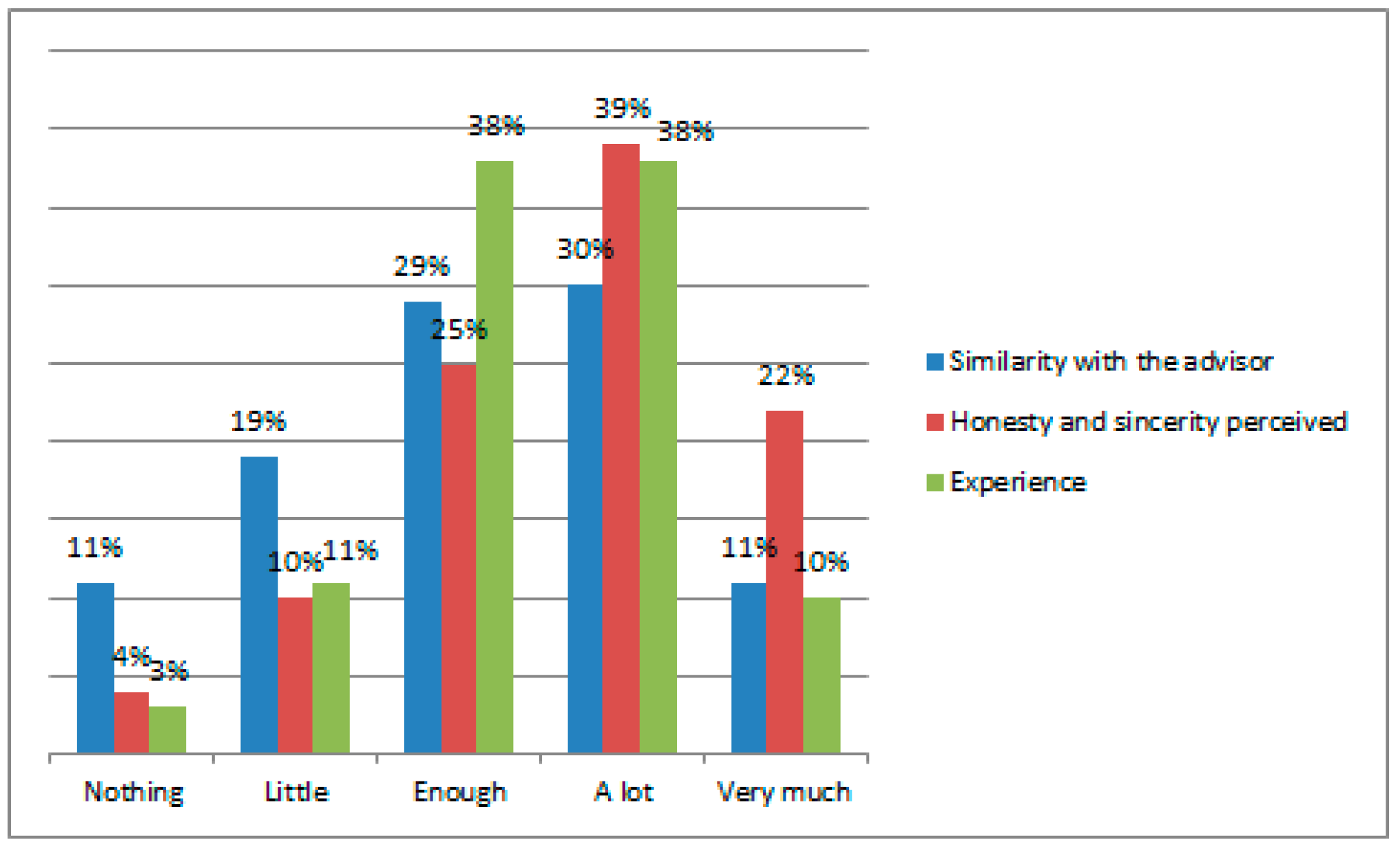

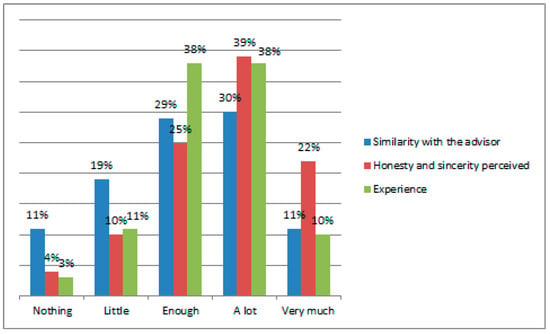

Finally, consumer attitudes play an important role because trust was seen to be affected significantly by the consumers’ perception in reading the reviews, in particular by the perception of honesty and sincerity in the reviews (39%) or similarity with the reviewer (30%). The consumer’s past positive or negative experiences (38%) also affected the CPOR (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Consumer variables affecting trust of online reviews.

5. Hypothesis Testing and the CONCEPT Model

Cronbach’s alpha values have been computed to verify the internal consistency of the items. All were significantly high (from 0.70 to 0.83 across the four constructs). Factors with a Cronbach’s alpha lower than 0.6 are considered unacceptable [65]. The analysis indicates acceptable internal reliability as the alpha coefficients of all constructs were above 0.6.

Table 2 show the Pearson’s correlation coefficients, giving us a picture of the relationships among variables in the proposed model. Thirteen hypotheses were formulated within four constructs that include them. The three hypotheses formulated within the construct of website quality produced strong and highly significant results. The first hypothesis (H1) stated a positive relationship between website usability and CPOR. The correlation test found a significant correlation (B = 0.40, p < 0.01), suggesting that CPOR increases as information quality increases. Therefore, H1 is supported by the data. The second hypothesis (H2) stated that website brand positively affects CPOR. The correlation test supported this hypothesis (B = 0.45, p < 0.01). This finding implies that people trust most information in websites with a strong brand. Finally, the third hypothesis (H3) proposed a positive relationship between website reputation and CPOR. This hypothesis is supported by a correlation coefficient of B = 0.40, p < 0.01. It can be assumed that the greater the website reputation, the greater the increase in CPOR. The study found also that brand and reputation (B = 0.65, p < 0.01) are strictly correlated.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between model variables.

The data partially supported the hypotheses formulated within the construct of advisor quality. The fourth hypothesis (H4) proposed a positive relationship between advisor expertise and CPOR. It was confirmed by data: B = 0.28, p < 0.01. These data suggest that when people read online reviews, they examine information about the advisor, that person’s experience, and the number of reviews made. However, the fifth hypothesis (H5), stating a positive relationship between advisor identity and CPOR, is not supported by correlation. This can be explained by the fact that consumers think that reviewer anonymity is related not to the writing of fake reviews but to a wish for privacy. Thus, the hypothesis is rejected.

The relationships predicted by hypotheses within the construct of message quality are supported by the data, which show that readability of a message (H6) (B = 0.25, p < 0.01), review sidedness (H7) (B = 0.30, p < 0.01), and review consistency (H8) (B = 0.38, p < 0.01) affect CPOR. These data indicate that message content is an essential construct in the credibility process. In particular, two-sided reviews are perceived as more credible than reviews stating very positive or very negative aspects.

Finally, the data supports the hypotheses formulated within the construct of consumer attitudes. H9, which stated a positive relationship between consumer experience and CPOR, is confirmed (B = 0.49, p < 0.01). Support is also shown for H10 and H11, which predicted a positive effect between perceived similarity to the advisor and CPOR (B = 0.24, p < 0.01) and between perceived honesty and sincerity of the advisor and CPOR (B = 0.30, p < 0.01). The data show that consumers who have experience in reading reviews can better understand whether a review is true. Moreover, when consumers perceive that the advisor has lifestyles and preferences similar to him or her, the review seems to be more credible. The same thing happens if consumers perceive the review as honest and sincere. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 2.

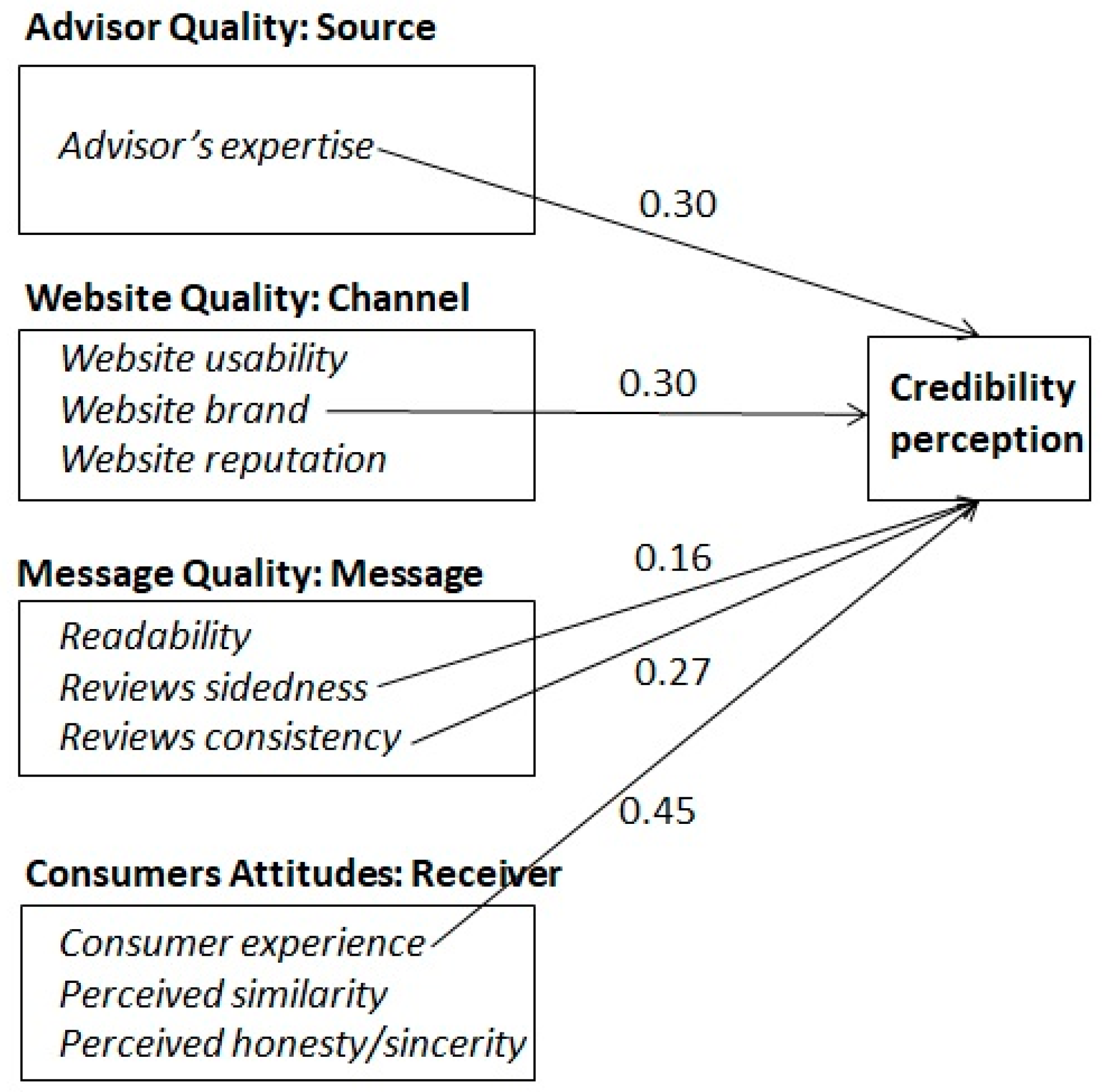

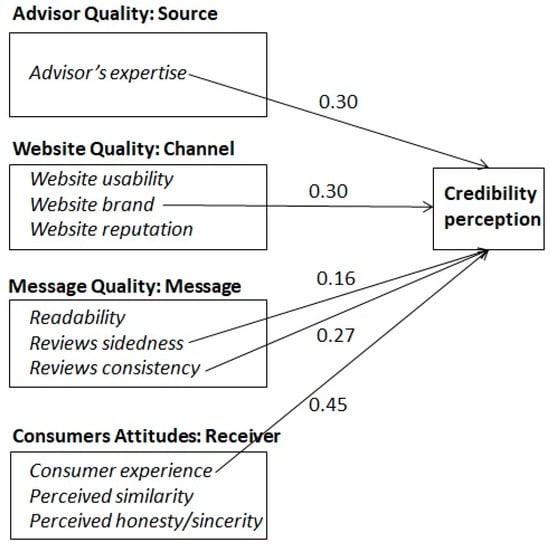

A multiple linear regression on the predictable variables and dependent variable (credibility perception) returned results showing that the reviewer’s identity, readability of the review, perceived similarity with the advisor, and perceived honesty/sincerity of the review are not significant predictors of CPOR. Website usability and reputation are weak predictors. Instead, the following variables are significant predictors of CPOR: website brand (coefficient for standardized Beta (B) and t value of B = 0.30, t = 5.68, p < 0.01); expertise of the advisor (B = 0.30, t = 7.32, p < 0.01); review sidedness (B = 0.16, t = 4.06, p < 0.01); review consistency (B = 0.27, t = 6.47, p < 0.01) and consumer experience (B = 0.45, t = 10.57, p < 0.01).

Starting from the analysed data, a new model of the CPOR process, called the CONCEPT model (CONsumers’ Credibility percEPTion), was developed (Figure 6). The CONCEPT model is based on the idea that the process of CPOR is affected by different constructs and variables. The process starts with a travel project of a consumer; in fact, when a consumer has the intention to travel, he or she generally searches for information about it and reads online reviews by other consumers. This process is influenced by age, in fact, there is a negative relationship between age and credibility ((B = −0.28, p < 0.01). These data suggest that increasing age, the credibility of online reviews decreases.

Figure 6.

CONsumers’ Credibility percEPTion (CONCEPT) model.

The CONCEPT model, defined according to the correlation and regression results, shows that in the CPOR process four main constructs must be considered: (a) advisor quality (source); (b) message quality (message); (c) website quality (channel); and (d) consumer attitudes (receiver).

The variables that comprise the four constructs act as variables of input in the process of CPOR. Three variables concerning the website quality construct are considered in credibility perception: website usability, reputation, and brand. These variables affect consumers’ trust, although only the brand is seen as a significant predictor of CPOR. The variables that comprise advisor quality are the reviewer’s identity and expertise—meaning the reviewer’s knowledge, skill, and ability in providing correct and valid information; this last variable is seen as a significant predictor of CPOR.

Furthermore, the message quality construct has an important role, as the variables that comprise it—readability, review sidedness, and review consistency—have a positive relationship with consumer trust, and the last two variables are significant predictors of the perception of credibility. Finally, the fourth construct, consumer attitudes, is very important because consumer perceptions influence the other variables and consumer trust. In particular, consumer experience is a significant predictor of credibility perception. All integrated factors affect the CPOR process, then the travel decision, and subsequently the purchase.

6. Conclusions

This study describes a new model developed and tested: the CONsumers’ Credibility percEPTion (CONCEPT) model, which introduces a set of variables that characterise the process of CPOR and trust in tourism context. This model was built based on findings of a survey carried out in Italy. The CONCEPT model identifies factors affecting consumer trust and the CPOR process. Specifically, this study empirically validates the model based on the social influence of online reviews and the extensive set of relationships among variables and their effect on CPOR and the travel decision-making process.

The study found four main constructs acting in the process of CPOR and influencing online purchases. These constructs are borrowed from the model of communication of Shannon and Weaver: source (expertise of reviewer), message (readability, review sidedness, and consistency), channel (website usability, reputation, and brand), and receiver (consumer experience, perceived similarity with the advisor, perceived honesty/sincerity of the review). Unlike other models discussed in literature that analysed characteristics of online review messages and structure and the message source as isolated and stand-alone perspectives our model has a better explanatory power because includes four different factors: source, message, channel, and receiver in an integrated way to analyse which have a greater influence on CPOR.

Most of the formulated hypotheses are supported by the data. The correlation test, in fact, found a significant correlation among variables. Only hypothesis 5, which stated a positive relationship between advisor identity and CPOR, was rejected; this variable was then omitted from the final model. Unlike previous studies [17,18,19] found that identity of reviewer influences credibility perception. Furthermore, other studies in literature focused mainly on the characteristics of online review messages and structure [12,13,14,15] and the message source [14,16,17,18,19] looking at these factors as isolated and stand-alone perspectives. Our model addresses this gap including these factors in an integrated way to analyse which have a greater influence on CPOR.

The linear regression found that significant predictors of credibility perception are website brand, advisors’ expertise, review sidedness, review consistency, and consumer experience. Other variables—readability of the review, perceived similarity with the advisor, perceived honesty/sincerity of the review—even if have a positive relationship with trust, are not significant predictors of credibility perception. Website usability and reputation are weak predictors of trust.

The CONCEPT model has some practical implications. First, it contributes to the scientific debate on online consumers’ perceived trust and credibility, indicating the factors that can influence these issues. Second, this model can be used by tourism marketers and companies to understand what factors affect online review credibility from consumers’ point of view and how they affect the decision-making process when booking a tourism service. The optimization of digital channels and e-commerce (understood as “everywhere commerce”) will be decisive factors for the Italian tourism sector after COVID-19. Social media are of particular importance as they are essential for drawing inspiration, searching for information, sharing the experience during and after the trip. Therefore, supply chain companies can no longer ignore this phenomenon. Companies should improve their strategies on social media by promoting their brand and increasing consumers’ trust in the context of online reviews. Tourism companies could significantly increase their revenues and profits by increasing their online visibility and brand. Moreover, online reviews have also an impact on destination trust and travel intention. Online reviews represent the real motivation that pushes tourists to choose a certain operator or destination in several cases. Negative online reviews in fact create a sense of distrust toward the destination and their intention to travel that is reduced even more when there is stronger emotional intensity of a review [66]. Some strategies are needed to address this issue. Companies should invite their satisfied customers to leave positive reviews on social media; this would greatly affect a positive impact of trust toward the brand, because social media are considered trustworthy and credible. In fact, the level of social presence in social media (e.g., personal information, photos, videos, and audios) has a positive effect on perceived usefulness and source credibility [67].

Furthermore, at the end of an online purchase, a promotion or a discount code can be sent to customers as a reward for feedback received through reviews. Some hotels instead manage their reputation by manipulating reviews. Still, this strategy can be counterproductive because consumers are increasingly experienced and tend to distrust TripAdvisor reviews due to the lack of a verification mechanism. Instead of using manipulation strategies, companies should respond to all types of online reviews, both positive and negative, thanking consumers and in the case of negative reviews apologizing for any inconvenience and explaining the causes of it. The study of Casado-Díaz et al. [68], in fact, showed that consumers have a significant attitude change toward negative comments, regardless of the type of managerial response. Moreover, websites containing travel reviews should invest more resources in developing additional verification mechanisms of reviews to avoid compromising their trustworthiness and highlight advisors’ expertise in reviews to improve CPOR.

Although this study contributes to a better understanding of the CPOR process, it has some limitations. First, the sample comprises only Italian respondents, and people could have different characteristics and behaviours in other countries. Moreover, although the sample included different people per age, gender, and educational level, the participants were engaged among the Internet users (particularly recruiting participants among travel groups members and Facebook blogs). Thus, the sample is diversified but not representative. One of the limits of linear regression is the nonlinearity in the relationships between the different variables. We will address these issues in future works by using a nonlinear SEM. Indeed, it allows modelling a nonlinear relationship between the latent variables, for example, quadratic and interaction effects amongst the latent variables.

In this first study we analysed the domestic market segment; for future studies we will extend this study both to the external market segment analysing the international tourism to Italy and to other countries to reach more detailed results and understanding about the CPOR process. Moreover, the model developed in this study could be tested across different sectors and product categories to generalize the results. In future works we will analyse also other independent variables that can affect Credibility Perception of Online Reviews (CPOR), such as satisfaction of previous users and social influence and will test the concept of circularity of the model by using structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F., P.G. and T.G.; methodology, F.F., P.G. and T.G.; validation, F.F., P.G. and T.G.; formal analysis, T.G.; investigation, F.F., P.G. and T.G.; data curation, T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.F., P.G. and T.G.; writing—review and editing, T.G.; supervision, P.G. and T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article has been produced collecting data following all the requirements according to GDPR. The survey did not collect any personal or sensitive data and it was not possible to obtain them. For this reason, this statement was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study as it was contained at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions according to the informed consent signed by the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Caschera, M.C.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Multidimensional visualization system for travel social networks. In Proceedings of the ITNG’09. Sixth International Conference—Information Technology: New Generations, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–29 April 2009; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1510–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, T.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P. ECA: An E-commerce consumer acceptance model. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 8, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, T.; D’Andrea, A.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P. A framework to promote and develop a sustainable tourism by using social media. In Proceedings of the OTM Confederated International Conferences—On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems, Graz, Austria, 9–13 September 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 656–665. [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj, T.; Dayal, M. Social media: Collaborating web 2.0 and user-generated content (UGC). Int. Multidiscip. J. Appl. Res. 2014, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Social aspects of mobile technologies on web tourism trend. In Social Computing: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 896–910. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Factors determining mobile shopping. A theoretical model of mobile commerce acceptance. Int. J. Inf. Processing Manag. (IJIPM) 2013, 4, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Méndez, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. The influence of e-word-of-mouth on travel decision-making: Consumer profiles. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1001–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. Destination Insights with Google. 2021. Available online: https://destinationinsights.withgoogle.com/intl/it_ALL/ (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Andersson, A.C. The manager’s dilemma: A conceptualization of online review manipulation strategies. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, P.; Ferri, F.; Guzzo, T. CREMOR: CREdibility model on online reviews: How people consider online reviews believable. Int. Bus. Res. 2017, 10, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Law, R.; Zhang, Z. Effects of online reviews and managerial responses from a review manipulation perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 2207–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.Y.; Sia, C.L.; Kuan, K.K. Is this review believable? A study of factors affecting the credibility of online consumer reviews from an ELM perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.S.; Yao, S.S. What makes hotel online reviews credible? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausczik, Y.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 29, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Li, Y.F.; Fan, P. Effect of online reviews on consumer purchase behavior. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumasondjaja, S.; Shanka, T.; Marchegiani, C. Credibility of online reviews and initial trust. The roles of reviewer’s identity and review valence. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Gretzel, U. Creating more credible and persuasive recommender systems: The influence of source characteristics on recommender system evaluations. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Kantor, P.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 455–477. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Miao, L.; Kuo, P.J.; Lee, B.Y. Consumers’ responses to ambivalent online hotel reviews: The role of perceived source credibility and pre-decisional disposition. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Assaker, G. Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Internet Res. 2012, 22, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.; Janis, I.; Kelley, H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.J.; Flanagin, A.J.; Eyal, K.; Lemus, D.; McCann, R. Credibility in the 21st century: Integrating perspectives on source, message, and media credibility in the contemporary media environment. Commun. Yearb. 2003, 27, 293–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loda, M.D.; Teichmann, K.; Zins, A.H. Destination websites’ persuasiveness. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 3, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. Do we believe in TripAdvisor? Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude toward using user-generated content. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Alcocer, N. A literature review of word of mouth and electronic word of mouth: Implications for consumer behavior. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Xiang, Z.; Josiam, B.; Kim, H. Personal profile information as cues of credibility in online travel reviews. Anatolia 2013, 25, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, R.W.; Blose, J.; Pan, B. Believe it or not: Credibility of blogs in tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnini, V.P. The implications of company sponsored messages disguised as word-of-mouth. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Schulze, H.; Spiller, A. The impact of online reviews on the choice of holiday accommodations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Law, R., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manganari, E.E.; Dimara, E. Enhancing the impact of online hotel reviews through the use of emoticons. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chen, S.W. The impact of online store environment cues on purchase intention: Trust and perceived risk as a mediator. Online Inf. Rev. 2008, 32, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with Visual Display Terminals (VDTs)—Part 11: Guidance on Usability. 1998. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Ergonomic-requirements-for-office-work-with-visual/17e53f6fa806ea573e4ee0904fbb12c3a527d5f0 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Nayanajith, G.; Damunupola, K.A.; Ventayen, R.J.M. Website Usability, Perceived Usefulness and Adoption of Internet Banking Services in the Context of Sri Lankan Financial Sector. Asian J. Bus. Technol. Stud. 2019, 2, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad, R.; Aslam, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Iqbal, M.W. Web Usability and User Trust on E-commerce Websites in Pakistan. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, D.; Basinska, B.A.; Sikorski, M. Impact of usability website attributes on users’ trust, satisfaction and loyalty. Soc. Sci. 2014, 85, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, Z.; Benyoucef, M. Usability and credibility of e-government websites. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, N.E.; Mackiewicz, J. A usability analysis of municipal government website home pages in Alabama. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, H.; Khan, M.A.; ur Rehman, K.; Ali, I.; Wajahat, S. Consumer’s trust in the brand: Can it be built through brand reputation, brand competence and brand predictability. Int. Bus. Res. 2010, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Hsu, C.L.; Chen, M.C.; Kuo, N.T. How a branded website creates customer purchase intentions. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poturak, M.; Softic, S. Influence of social media content on consumer purchase intention: Mediation effect of brand equity. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 12, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Kuo, N.T.; Hsu, C.L.; Cheng, Y.S. The impact of website quality and perceived trust on customer purchase intention in the hotel sector: Website brand and perceived value as moderators. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2014, 5, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S. Segmenting consumer decision-making styles (CDMS) toward marketing practice: A partial least squares (PLS) path modeling approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R.; Schweitzer, M.E. Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bian, J.; Zhu, W. Trust fraud: A crucial challenge for China’s e-commerce market. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 12, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Estimating the helpfulness and economic impact of product reviews: Mining text and reviewer characteristics. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2011, 3, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieh, S.Y. Judgment of information quality and cognitive authority in the web. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2002, 53, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gobinath, J.; Gupta, D. Online reviews: Determining the perceived quality of information. In Proceedings of the International Conference—Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Jaipur, India, 21–24 September 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 412–416. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M.J.; Wirtz, B.W.; Weyerer, J.C. Determinants of online review credibility and its impact on consumers’ purchase intention. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, C.H.; Lim, S.L.; Lwim, M. Word-of-mouth communication in Singapore: With focus on effects of message-sidedness, source and user-type. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 1995, 7, 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Watts, S. Knowledge Adoption in Online Communities of Practice. Syst. D’inf. Manag. 2016, 21, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Chen, H.S. To buy or not to buy? Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions for suboptimal food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.C.C.; Lam, L.W.; Chow, C.W.; Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R. The effect of online reviews on hotel booking intention: The role of reader-reviewer similarity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pentina, I.; Bailey, A.A.; Zhang, L. Exploring effects of source similarity, message valence, and receiver regulatory focus on yelp review persuasiveness and purchase intentions. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F.; Tsui, B.; Lin, Z. Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 956–970. [Google Scholar]

- AGI. Agenzia Italia. Presenze e giro D’affari del Turismo Straniero in Italia. Available online: https://www.agi.it/economia/news/2020-05-15/numeri-turismo-straniero-italia-tracollo-coronavirus-8615132/ (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- ISTAT. Conto Satellite del Turismo per L’Italia, Anticipazione anno 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2021/09/Conto-satellite-turismo-2020.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- ISNART. Turismo: Con il Covid 6,5 Milioni di Italiani in Meno in Vacanza D’estate. 2020. Available online: https://www.isnart.it/news/turismo-con-il-covid-65-milioni-di-italiani-in-meno-in-vacanza-destate/ (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Digital Innovation Observatory. Il Mercato del Turismo Digitale in Italia. 2018. Available online: http://www.osservatori.net (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Hung, K.; Law, R. An overview of Internet-based surveys in hospitality and tourism journals. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 717–724. [Google Scholar]

- Influence. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/influence (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Ha, I.; Yoon, Y.; Choi, M. Determinants of adoption of mobile games under mobile broadband wireless access environment. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Yang, Q.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, N.C. The impact of online reviews on destination trust and travel intention: The moderating role of online review trustworthiness. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 13567667211063207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Koo, C. Adoption of travel information in user-generated content on social media: The moderating effect of social presence. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 34, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Andreu, L.; Beckmann, S.C.; Miller, C. Negative online reviews and webcare strategies in social media: Effects on hotel attitude and booking intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 23, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).