Lessons Learned from an Intersectoral Collaboration between the Public Sector, NGOs, and Sports Clubs to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Youths

Abstract

1. Introduction

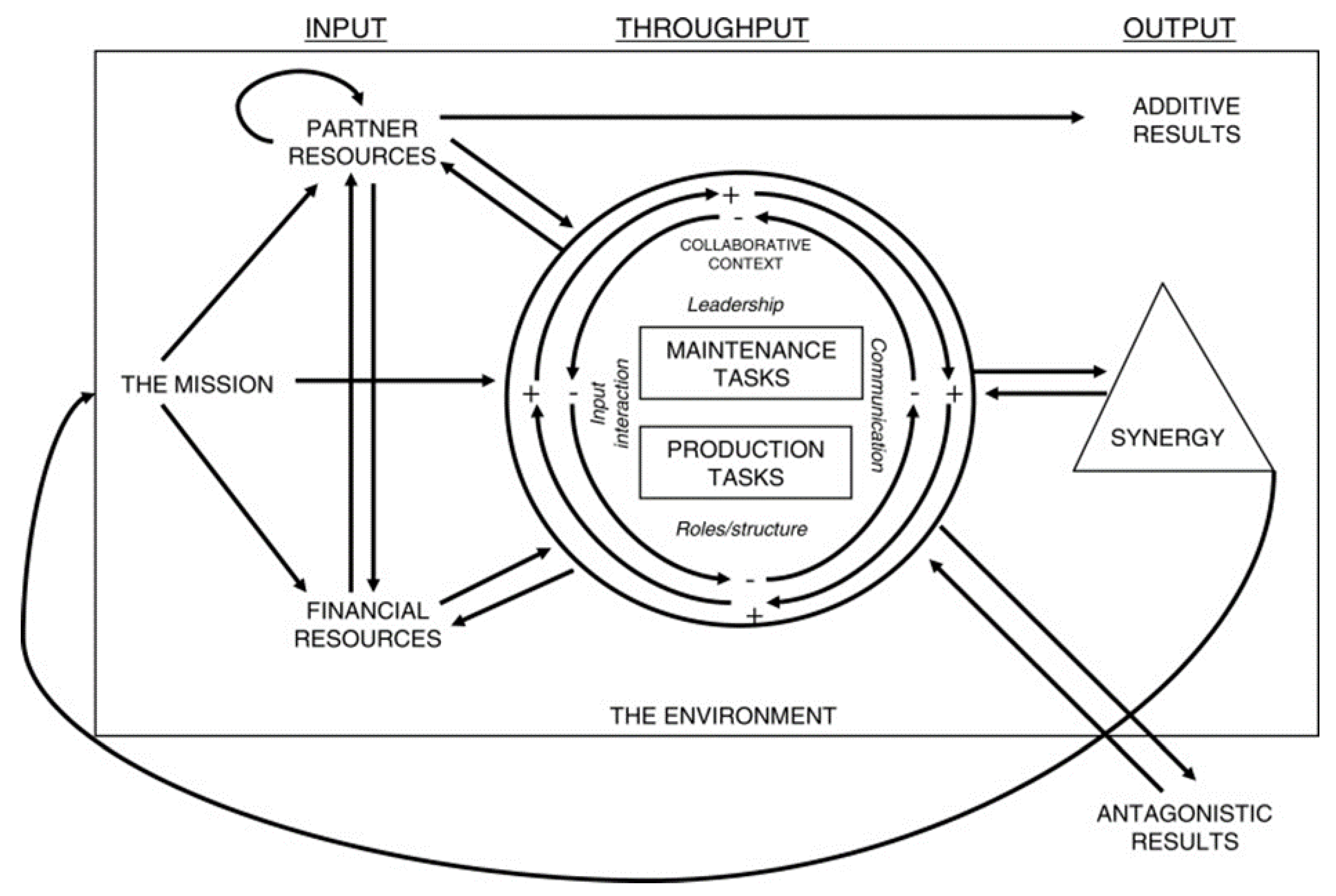

1.1. Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning

1.2. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Method

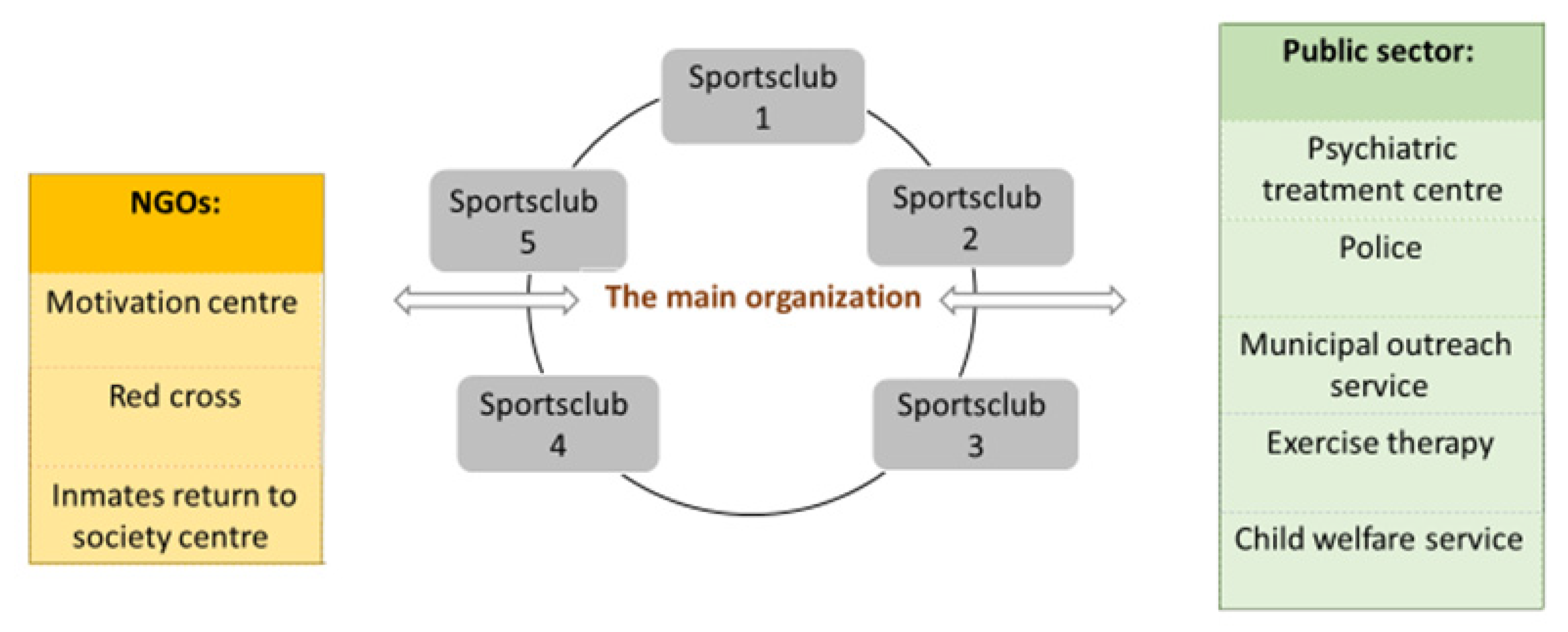

2.1. The Sports Project

2.2. Participants and Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Input Phase

“We all want the same thing. We work with drug and crime prevention. We want to prevent people from continuing in such a career. This is something that the public sector also wants. So I guess we all work for the same goal. We will have a safer society if this group can get away from drugs and crime through activity and new interests. Therefore, I reckon that everyone has a common goal; To prevent this through activities.”(Informant, NGO)

“I feel that everyone knows that these young people need an arena, they need a safe place where they can cope... and that is a common goal for all partners. So the goal is the same, but we have different networks where we meet the youth and bring them to the project. It appears relatively… homogeneous: a common goal.”(Informant, Public sector)

“The activity itself is secondary. My job is not to get the youth in the best possible physical shape. My job is about everything that happens around the activity”(Informant, Main Organization)

“For us, it is important to know that my patients will be taken care of. To join the activity is considered a big risk for the youth here. And if they do not feel welcome, it is almost worse than if they did not go at all. So the consequences are high.”(Informant, Public sector)

“When we work with such a complex target group, we have to consider multiple factors. (…). We have a lot of knowledge about activity and sport, but there is so much more to consider in this case. We need the knowledge from the professionals who work with this group.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“Our partners are busy with hectic workdays, which makes it hard to plan meetings. It is a challenge for the collaboration group to grow.”(Informant, Main Organization)

”I believe that it is easier to cooperate with us because we “take care of” the financial part. When it comes to questions about finances, there are many who do not have the opportunity to contribute. Collaboration also becomes more complicated with a shared budget”(Informant, Main Organization)

“When you have good projects and projects with high relevance, it’s easier to apply for financial support. And this (the project) is something that people are passionate about.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“It is important to show the employees that if the fundings we apply for will not come, we have a buffer. The sports sector often provides jobs that are not secure, and a lot of work is done voluntarily. But we expect more from the coordinators in the main organization, and that’s why it’s important to give more.”(Informant, Main Organization)

3.2. Throughput Phase

“It is a place where you feel that you can contribute. Together you get this ownership-feeling of the project. You can see the others, and people are listening to what you say.”(Informant, Public sector)

“When you bring in patients with different problems to us, there is a risk associated with that (...) So when we experience partners such as institutions and clinics bringing youths and patients to us regularly, I hope that it is an indication that we are doing a good job and that they trust us.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“You have to be somewhat altruistic and pragmatic going into a collaboration such as this, but the public sector is pretty rigid: “this is our responsibility, and this is not our responsibility.” If the patient is admitted, they can handle the expenses, but the municipality has to “take it” if the patient quits. And if you are constantly thinking in these rigid ways, the collaboration doesn’t work. Or it becomes challenging to collaborate.”(Informant, Public sector)

“They have skilled people working there. They are extremely engaged who work to become better. People who start projects often get lazy, but not these people. They have been devoted to their work.”(Informant, NGO)

3.3. Output Phase

“We would not have been able to find the people who are with us today if it had not been for the collaboration. (…) Without the collaboration, nothing would have happened”(Informant, Main Organization)

“One thing is that the partners of the collaboration regularly meet during the project., but it may also contribute to the partners getting a better collaboration and knowledge about each other in other contexts. We can see that during our meetings, other ideas and collaborations come up.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“Some of those participating in the collaboration want to create a network. Some partners are relatively new (...) But it does not overshadow the goal of this collaborative project. But they have “side-goals,” where the collaboration can help them in raising awareness for their organization.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“It is unique for the collaboration that five sports clubs have come together to collaborate about this. And by doing so, we have created an arena for us to discuss other issues. It makes us stronger.”(Informant, Main Organization)

“After a while, more participants could volunteer here. Because many want to contribute and that is nice. It becomes a win-win situation where they can fill their days with something meaningful, and we get new volunteers.”(Informant, NGO)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Value of a Common Mission and Goal

4.2. The Value of Complementary Skills and Roles

4.3. The Value of the User Perspective

4.4. The Value of Synergies

4.5. Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning in a New Context

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Further Research

6. Conclusions

- a common goal

- sufficiently invested partner resources, including financial resources

- perceived relevance of the project

- partners with clear roles and responsibilities within the collaboration

- a strong user perspective and user-oriented approach in the activity choice

- a rule-bound and not as flexible public sector challenging the collaboration process

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health for the World’s Adolescents: A Second Chance in the Second Decade; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/second-decade/en/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows. Public Health 2021, 199, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willumsen, E.; Ødegård, A. Tverrprofesjonelt Samarbeid et Samfunnsoppdrag [Intersectoral Collaboration a Societal Mission], 2nd ed.; Universitetsforlaget AS: Oslo, Norway, 2016. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Health in All Policies (HiAP) Framework for Country Action. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, R.; Axelsson, S.B. Samverkan og folkhälsa-begrepp, teorier og praktisk tillämning. In Folkhälsa i Samverkan Mellan Professioner, Organisationer och Samhällssektorer [Public Health in Coordination with Professionals, Organizations and Society]; Axelsson, R., Axelsson, S.B., Eds.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2007; pp. 11–31. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Fosse, E.; Helgesen, M. Advocating for health promotion policy in Norway: The role of the county municipalities. Societies 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Care Services, Government of Norway; Lov om Folkehelsearbeid [Public Health Act], No. 29, 24-06-2011. 2011. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-29 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Aarø, L.E.; Klepp, K.I. Ungdom, Livsstil og Helsefremmende Arbeid [Youth, Lifestyle and Health Promotion], 4th ed.; Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS: Oslo, Norway, 2017. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Folkestad, B.; Christensen, D.A.; Strømsnes, K.; Selle, P. Frivillig Innsats i Noreg 1998–2014. In Kva Kjenneteikner dei Frivillige og Kva har Endra Seg? [Voluntary Effort in Norway: What Characterizes NGOs and What Has Changed?]; Rapport 4/2015; Senter for Forskning på Sivilsamfunn og Frivillig Sektor: Oslo, Norway, 2015. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M.; Rantala, R.; Koudenburg, O.A.; Gulis, G. Intersectoral action for health: The experience of a Danish municipality. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, D.H.; Frohlich, K.L.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T.; Clavier, C. Intersectoriality in Danish municipalities: Corrupting the social determinants of health? Health Promot. Int. 2016, 32, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synnevåg, E.; Amdam, R.; Fosse, E. Intersectoral planning for public health: Dilemmas and Challenges. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldeide, O.; Fosse, E.; Holsen, I. Collaboration for drug prevention: Is it possible in a “siloed” governmental structure? Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, e1556–e1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldeide, O.; Fosse, E.; Holsen, I. Local drug prevention strategies through the eyes of policy makers and outreach social workers in Norway. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2020, 29, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlén, J.; Stenling, C. Same same, but different? Exploring the organizational identities of Swedish voluntary sports: Possible implications of sports clubs’ self-identification for their role as implementers of policy objectives. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 5, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D. Midnight Basketball: Race, Sports, and Neoliberal Social Policy; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, J.R. A contract reconsidered? Changes in the Swedish state’s relation to the sports movement. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2011, 3, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermenes, N.; Koelen, M.A.; Verkooijen, K.T. Associations between partnership characteristics and perceived success in Dutch sport-for-health partnerships. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virokannas, E.; Liuski, S.; Kuronen, M. The contested concept of vulnerability—A literature review. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2020, 23, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almqvist, A.L.; Lassinantti, K. Social work practices for young people with complex needs: An integrative review. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2018, 35, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lögdberg, U.; Nilsson, B.; Kostenius, C. “Thinking about the future, what’s gonna happen?” How young people in Sweden who neither work nor study perceive life experiences in relation to health and well-being. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1422662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follesø, R. Youth at risk or terms at risk? YOUNG 2015, 23, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.H.; Fernandez, M.E.; Mullen, P.D. Evaluation of a community–academic partnership: Lessons from Latinos in a network for cancer control. Health Promot. Pract. 2015, 16, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, J.H.; Mittelmark, M.B.; Lie, G.T. Grassroots volunteers in context: Rewarding and adverse experiences of local women working on HIV and AIDS in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Glob. Health Promot. 2015, 23, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, H.; Corwin, L.; Mittelmark, M.B. Producing synergy in collaborations: A successful hospital innovation. Innov. J. Public Sect. Innov. J. 2012, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.H.; Mittelmark, M.B. Partnership Lessons from The Global Programme of Health Promotion Effectiveness: A Case Study. Health Promot. Int. 2008, 23, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, J.H.; Jones, J.; Barry, M.M. What makes intersectoral partnerships for health promotion work? A review of the international literature. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 33, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Metoder for Medisin og Helsefag [Qualitative Methods for Health Sciences], 4th ed.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2017. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, L. Factors and Processes that Facilitate Collaboration in a Complex Organisation: A Hospital Case Study. Master’s Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. Available online: https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/handle/1956/4453 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Voorberg, W.H.; Trummers, L.; Bekkers, V.; Torfing, J.; Tonurist, P.; Kattel, R. Co-Creation and Citizen Involvement in Social Innovation: A Comparative Case Study Across 7 EU-Countries; LIPSE Report; EU Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A. Partnership Working across UK Public Services Edinburgh: What Works Scotland. 2015. Available online: http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/WWS-Evidence-Review-Partnership-03-Dec-2015-.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Ekmann, L.; Siversten, H.; Stene, M.; Lysø, R. Samarbeid for Barn og Unges Oppvekstmiljø [Collaboration for Children and Youths]; Erfaringer Fra Samarbeid Mellom Kommune og Frivillighet i STEINKJER Kommune; TFoU-Rapport 2017:07; Trøndelag Forskning og Utvikling AS: Trondheim, Norway, 2017. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- Casey, M.M.; Payne, W.R.; Brown, S.J.; Eime, R.M. Engaging community sport and recreation organisations in population health interventions: Factors affecting the formation, implementation, and institutionalisation of partnerships efforts. Ann. Leis. Res. 2009, 12, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estacio, E.V.; Oliver, M.; Downing, B.; Kurth, J.; Protheroe, J. Effective Partnership in Community-Based Health Promotion: Lessons from the Health Literacy Partnership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Co-Creation in Social Innovation: A Comparative Case-Study on the Influential Factors and Outcomes of Co-Creation 2014, Department of Public Administration, Rotterdam. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/20116379.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Care Services, Government of Norway. The Coordination Reform, St. Meld nr 47 2008–2009; Departementenes Servicesenter: Oslo, Norway, 2009.

- Jensen, C.; Trägårdh, B. Temporära Organisationer för Permanenta Problem, Skrifter Från Temagruppen Unga i Arbetslivet 2012, Stockholm, Temagruppen Unga. 2012. Available online: http://www.temaunga.se/sites/default/files/Rapporter/temporara_mini.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Jones, J.; Barry, M.M. Exploring the relationship between synergy and partnership functioning factors in health promotion partnerships. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, C.C.G.; Fredriksson, I.; Fröding, K.; Geidne, S.; Pettersson, C. Academic practice–policy partnerships for health promotion research: Experiences from three research programs. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, S.; Hetherington, S.A.; Borodzicz, J.A.; Hermiz, O.; Zwar, N.A. Challenges to establishing successful partnerships in community health promotion programs: Local experiences from the national implementation of healthy eating activity and lifestyle (HEAL[TM]) program. Health Promot. J. Aust 2015, 26, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermens, N.; de Langen, L.; Verkooijen, K.T.; Koelen, M.A. Co-Ordinated action between youth-care and sports: Facilitators and barriers. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2017, 25, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, I.; den Hertog, F.; van Oers, H.; Schuit, A.J. How to improve collaboration between the public health sector and other policy sectors to reduce health inequalities?—A study in sixteen municipalities in the Netherlands. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.J.; Edwards, M.; Bocarro, K.; Bunds, J.; Smith, W. Collaborative Advantages: The Role of Interorganizational Partnerships for Youth Sport Nonprofit Organizations. J. Sport Manag. 2017, 31, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture, Rapport fra Strategiutvalget for Idrett: Statlig Idrettspolitikk Inn i en ny Tid [Governmental Sports Politics in a New Era]. Rapport 6/2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/3ab984dc671847bebe9a1cd2ec11f0ec/statlig-idrettspolitikk-inn-i-en-ny-tid.-rapport-fra-strategiutvalg-for-idrett.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Kokko, S.; Torp, S.; Ringsberg, K.C.; South, J. Health promotion by communities and in communities: Current issues for research and practice. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vandermeerschen, H.; Vos, S.; Scheerder, J. Who’s joining the club? Participation of socially vulnerable children and adolescents in club-organised sports. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture and Church, Government of Norway. Volunteering for All, Meld. St. 39 2007–2008; Departementenes Servicesenter: Oslo, Norway, 2008.

- Kaehne, A. Integration as a scientific paradigm. J. Integr. Care 2017, 25, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loga, J.; Eimhjellen, I. Nye Samarbeidsrelasjoner Mellom Kommuner og Frivillige Aktører—Samskaping i Nye Samarbeidsforhold? [New Collaborative Relations Between Municipalities and NGOs—Cocreation in New Collaborations]; Rapport 2017/9; Senter for Forskning på Sivilsamfunn og Frivillig Sektor, Institutt for Samfunnsforskning: Oslo, Norway, 2017; ISBN 9788277635781. Available online: https://hvlopen.brage.unit.no/hvlopen-xmlui/handle/11250/2592124 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Guribye, E. Mot ‘Kommune 3.0’? Modeller for Samarbeid Mellom Offentlig og Frivillig Sektor: Med Hjerte for Arendal [Models for Collaboration Between the Public and NGOs], FoU-Rapport nr.3/2016; Agderforskning Kristiansand: Kristiansand, Norway, 2016; ISBN 9788276022674. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tell, D.; Oldeide, O.; Larsen, T.; Haug, E. Lessons Learned from an Intersectoral Collaboration between the Public Sector, NGOs, and Sports Clubs to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Youths. Societies 2022, 12, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010013

Tell D, Oldeide O, Larsen T, Haug E. Lessons Learned from an Intersectoral Collaboration between the Public Sector, NGOs, and Sports Clubs to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Youths. Societies. 2022; 12(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleTell, Disa, Olin Oldeide, Torill Larsen, and Ellen Haug. 2022. "Lessons Learned from an Intersectoral Collaboration between the Public Sector, NGOs, and Sports Clubs to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Youths" Societies 12, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010013

APA StyleTell, D., Oldeide, O., Larsen, T., & Haug, E. (2022). Lessons Learned from an Intersectoral Collaboration between the Public Sector, NGOs, and Sports Clubs to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Youths. Societies, 12(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010013