1. Introduction

The Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach [

1,

2] has become central to the current understanding of population health and health promotion globally. The foundation of the HiAP principle is to examine determinants of health that can be altered to improve health, which implies that these determinants are mainly controlled by sectors other than health [

1]. The approach highlights the importance of public policy and practice at all political levels and public and social sectors, ranging from international arenas to national, regional and municipality levels, to improve population health and health equity [

3,

4].

Of special interest is the municipality level where people live and thrive. However, gaps exist in the understanding of how HiAP works at this level, as shown by a scoping review of research published between 2006 and 2015 [

5], especially in the understanding of local strategies to diminish social inequalities in health [

6,

7]. The social gradient in health inequalities demonstrates that health worsens as one descends the socioeconomic ladder [

8,

9,

10] and levelling the social gradient is considered an important aim of public health policies, both globally [

2] and in Norway [

11,

12].

However, challenges of increased social inequalities in health, and the conditions for preventing or reducing poor health, are quintessentially complex and ‘wicked’ and do not fit within traditional organisational, jurisdictional, geographical, societal and/or functional boundaries, nor can they be effectively addressed by a single actor [

13]. In Norway, the HiAP approach was adopted as the main aim of the 2012 Public Health Act [

14,

15] to reduce social health inequalities, and Norway has been described as a forerunner in translating the HiAP approach to a specific policy and practice [

16,

17].

Norwegian national guidelines [

12,

18] introduce several structural means to level the social gradient and increase health equity by affecting the social determinants of health (i.e., through HiAP-inspired tools, such as planning cross-sectorally, executing municipal health overviews and employing PHCs at the local governance level [

11]). As such, the national policy ambitions and guidelines take a stronger ‘collectivist–integrative’ approach compared to an individualistic approach [

19,

20].

The Norwegian Public Health Act describes public health as an intersectoral concern relying on an HiAP approach for acting on the social determinants of health and reducing social health inequalities [

15]. Acting at the local government level is considered a necessary and viable way to affect the social factors impacting health.

Previous research has shown that the enactment of the Public Health Act has been important to increased use of HiAP tools in Norwegian municipalities [

17,

21]. Municipalities that developed health overviews after the act took effect were two and a half times more likely to prioritise fair distribution in political decision-making compared to municipalities that did not develop such overviews, albeit with a smaller degree of focus on fair distribution in municipal policymaking in general [

22].

The notion that both political and general social conditions are important drivers of social inequality and reduced health and quality of life in municipalities underlines that there are no simple solutions to this complex problem. The solution requires collective actions of several actors through a so-called whole-of-government approach [

23], which is the opposite of departmentalisation, or vertical silos, as often experienced in public sector organisations. The whole-of-government approach is based on integrating actors horizontally and vertically, aiming to solve complex policy issues.

In a complex public sector characterised by norms, traditions and path-dependencies, the implementation of such intersectoral approaches leads to relatively high levels of interdependency between actors, by which actors have to negotiate and to some extent combine their resources and knowledge to achieve qualitatively good outcomes [

24]. HiAP emphasises public health and health inequalities as a whole-of-government approach, recognising that health is influenced by factors beyond healthcare, including political, social and economic factors and physical surroundings, and that population health should be integrated within and across policy areas and organisational units [

20,

25].

In municipalities, the establishment of a specific position as a PHC is considered an important coordinating measure to monitor population health, organise public health policy and pay more attention to health inequalities at a local level [

10,

17,

19,

21,

22,

26]. The PHC position is not statutory but recommended by national policies. A considerable majority of Norwegian municipalities employ PHCs (86%). Despite this, two surveys conducted in 2011 and 2014 showed that only about one-third of Norwegian municipalities reported that they prioritised fair distribution among social groups in municipal political decision-making [

22]. The study concluded that the creation of the position of the PHC had a negative effect on how social inequality was recognised and prioritised politically in Norwegian municipalities. In fact, merely employing a PHC was found to reduce the capacity to advance local population equity [

22]. This is an interesting puzzle with no obvious explanation. The study of Hagen et al. (2018) resulted in a debate over whether organisational means, such as employing a PHC, are appropriate HiAP tools [

27,

28,

29].

In this study, we investigate how PHCs engage with local politics and their effort in framing public health issues on the agenda in local policymaking. We aim to understand how PHCs at the local level can realise public health policy goals and thereby contribute to the debate on how health inequalities should be abated at the local level. Until now, our knowledge of how PHCs operate in a municipal setting and how they perceive their roles in local policymaking is scarce. Are they successful in getting public health concerns embedded in all municipal policies, and does this have an impact on public health outcomes? We will address this lacuna by investigating two research questions: (1) What factors influence PHCs’ possibilities of acting as local intersectoral agents? (2) How do PHCs perceive their role and influence on public health policy?

1.1. Theory and Hypotheses

1.1.1. Municipal Context and Intersectoral Agency

Norway follows the principle that all municipalities, regardless of size and centrality, are assigned the same set of statutory tasks. To enable the municipalities to provide all kinds of services, the national tax system redistributes taxes between municipalities aimed at securing equal service for all inhabitants independent of where people reside. Following this principle, an inhabitant in a small outlying municipality has the same legal rights as an inhabitant in a large urban municipality. The municipality’s mandatory tasks are stated partly in the Local Government Act and special legislation like the Public Health Act, but they can take on all tasks that the legislation has not explicitly assigned to other administrative bodies [

30]. However, despite the negative definition of statutory tasks and implicitly local autonomy, most of the economic resources in the municipalities are predetermined to statutory tasks where care and education represent the two largest sectors [

31].

Norway has a municipality amalgamation process [

32], which reduced the number of municipalities from 428 to 356 by 1 January 2020. After the amalgamation reform, Norwegian municipalities are still characterised by small population sizes. The current (2020) median (25–75%) population size of Norwegian municipalities is approximately 5200 (2200–13,400) inhabitants, but only 25 of 356 municipalities (7%) have a population size of more than 40,000 inhabitants [

33].

In summary, Norway has a fragmented and diverse municipal structure characterised by many small and sparsely populated municipalities and a deeply embedded value of universalism and equality, as reflected in the principle of generalist municipalities [

34]. Municipalities are embedded in different contexts, such as population size, centrality, socioeconomic differences and general employment status. Such contextual differences affect the local governments’ possibilities and willingness to prioritise social equality in their policies. These large-scale frames also affect administrative (recruitment) and fiscal resources and may act as hindrances or drivers for the PHC to affect politicians in their public health deliberations.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The contexts of the municipality, such as population size, centrality, socioeconomic differences and unemployment within the municipality are associated with the degree of intersectoral agency.

1.1.2. Individual Characteristics and Intersectoral Agency

Public health is a de facto intersectoral subject more often than not dealing with complex or ‘wicked’ societal issues [

13], and thus does not fit within jurisdictional boundaries and administrative silos. The PHC’s role and function are in this way embedded in cross- and intersectoral cooperation and, as such, they cross different organisational and jurisdictional boundaries where trust and legitimacy are important [

35,

36,

37], implying that individual characteristics may be of importance [

38].

A PHC who acts as an intersectoral agent or boundary spanner [

39] can be seen as a ‘cultural mediator’ who needs to understand the organisation of others and make a real effort to empathise with and respect the values and perspectives of others [

40]. The dynamics and dilemmas of collaborative intersectoral processes are difficult because these individuals must be skilled at deconstructing boundaries between themselves and recipients to listen empathetically and build trust. They must also protect themselves from interference with the recipient’s problems. This is a balancing act between inclusion and separation and dependence and autonomy [

36,

41] and may imply that some specific individual characteristics are needed.

In the literature on boundary spanning and intersectoral agency, there are innumerable references to desirable personality and characteristic features of boundary spanners; it is suggested that they should be personal, honest, respectful, passionate, trustworthy, tolerant, diplomatic, caring and committed, among others [

40]. Most of these traits may be related to experience and self-awareness. In this study, we believe that more experienced PHCs to a greater degree than unexperienced will characterise themselves as intersectoral agents.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Individual characteristics such as gender, age, work experience and length of education are associated with the degree of intersectoral agency.

1.1.3. Organisational Factors and Intersectoral Agency

In the literature on policy entrepreneurs, these individuals or groups are generally regarded as elite- or high-level decision-makers who generate ideas, frame problems and disseminate information strategically to promote desired policy outcomes [

42,

43]. Placed higher in the organisational hierarchy, they have better preconditions for participation in overall municipal planning, cross-sectoral collaboration and coordinated approaches and action. In this line of thought, it may be fruitful to compare the notion of street-level policy entrepreneurs similar to how Lipsky defined frontline public service employees as street-level bureaucrats [

44,

45]. In an individualistic approach, street-level bureaucrats interact with people and can shape public policy ‘on the spot’, which can directly and indirectly impact the lives of people. Lipsky stated that policies are implemented at the meeting point between officials and the public, and that these meetings and the officials’ handling also create policy. A low-ranking PHC organised at lower organisational levels may thus not have the opportunity to directly affect the making of policies but may create momentum through their public health work, thereby leading to public and political awareness and indirectly affecting policies.

Intersectoral networks and co-ordination are growing in popularity and are claimed to be methods of re-configuring and re-engineering public services [

35] in a new collaborative public order. The collaborative work may be enriched by the variety of the actors involved but may also be blocked or disrupted by that diversity, especially if the collaborative members operate under different institutional (sectoral) logics and/or are only engaged in the collaboration part-time. Such collaborative networks within public health containing (often part-time) professionals with different backgrounds and agendas may be understood as organised anarchies [

46] where the professional who has access to resources, decision arenas as well as to decision-makers has the luxury of being the one who defines problems and their solutions.

We believe that some organisational conditions must be in place for a PHC to be able to function as an intersectoral agent enabling policy change. To negotiate solutions or agreements between several different parties is challenging, but the challenge may grow exponentially if the PHC does not have the necessary organisational legitimacy to act intersectorally. Hagen et al. (2018) found that for PHCs to succeed in reducing health inequalities, they need to possess sufficient organisational authority to coordinate municipal sectors and assist in developing and implementing policies [

22]. Such organisational conditions granting authority to PHCs can be related to the location of the position in the formal hierarchy, such as how close to the CEO the PHC is located and if it is a managerial position or not. Furthermore, the size of the position, and formal expectations of work performance such as a job description, can be of importance for the PHC’s authority and influence.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Organisational factors, such as placement in the administrative hierarchy, level of position, size of position and job description, are associated with the degree of intersectoral agency.

1.1.4. PHCs as Intersectoral Agents Affecting Budget and Policy Outcomes

Kingdon (2003) introduced policy entrepreneurship as a theoretical concept about the individual’s role in policy change [

47]. A PHC with access to resources, decision arenas and decision-makers can probably be described as a policy entrepreneur that combines streams of problems, solutions and political will [

48,

49], or a problem broker that frames conditions as public problems and works to make policymakers accept these frames [

49]. They are willing to invest resources (e.g., time, money and expertise) to either advocate for policy changes or resist them [

40]. Through strategic behaviour, they continuously attempt to draw attention and resources to their cause, lobby decision-makers, secure allies and disseminate supportive information to make the system amenable to change [

43]. The crucial question is whether they are impactful. Different scholars operationalise policy change differently. The success of policy entrepreneurs can be related to their activities throughout the policy process [

42,

50] or the policy outcome itself [

47,

51]. They are either able to set the agenda, change others’ preferences and/or obtain acceptance of their own solutions in policy documents [

43]. Given the complexity and ‘wickedness’ of tasks related to social inequalities in health, an HiAP perspective would argue that it is unlikely that a single actor could achieve this alone. Instead, in a municipal public health context, the PHC has to establish cooperation with other members of the organisation, either through coalitions or networks [

52].

Concerning national public health policy ambitions and guidelines [

18] that emphasise structural means such as planning, health overviews and cross-sectoral collaboration, the working arena for the PHC is within the administration. In this arena, the PHC needs to make public health issues visible through policy documents to both the top management and politicians.

Well known barriers to implementing public health measures in politics are lack of financial resources and lack of public and stakeholder awareness [

53]. Following Kingdon on policy entrepreneurs [

47], one important way a PHC can affect public health policy is through winning the budget fight through convincing other sectors, and in particular, the municipality CEO and other leaders at the top administrative level, that it is important to allocate financial resources to public health.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). PHCs acting as intersectoral agents affect policy through annual budgets.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional web-based survey aimed at PHCs in all Norwegian municipalities. The questionnaire consisted of 60 questions measuring different aspects of the work and organisational constitution of municipal public health work: personal and professional background, political and administrative organisation and prioritising, roles and influence and incorporation of public health in planning.

From January to February 2019, we collected email addresses through municipalities’ webpages or by direct telephone contact with the municipalities’ service desks. Through this process, we found 388 unique email addresses of a total of 428 municipalities (before the amalgamation reform). For the 40 remaining municipalities, we wrote to the official email address of the municipality with a request to forward our message to the responsible public health official. The questionnaire was handled through the survey instrument SurveyXact™, and the survey was sent to all respondents (n = 428) on 27 May 2019 with two email-based reminders on 4 and 20 June 2019. The survey was open through the summer holidays, and we performed telephone-based reminders to the non-responders by August 2019. The survey was closed on 4 September 2019.

The response rate based on all Norwegian municipalities (n = 428) was 60% (n = 256). The amalgamation reform, where 119 Norwegian municipalities were to merge into 47 larger units, was occurring through 2019. The merger was planned to be finished by the end of 2019, and most of the 119 municipalities had established collaborations in many fields, including public health work. We received responses from 41 of 47 collaborative municipal groups and, as such, the response rate may have been as high as 72%. The response rate varied by municipal size and was 47 of 95 (49.5%) in municipalities < 2000 inhabitants (n = 95) and 69 of 125 responses (55.2%) in municipalities between 2000 and 5000 inhabitants. The same pattern was seen in centrality, where we received responses from 51 of 125 (40.8%) of the least central municipalities.

2.1. Defining Intersectoral Agency

Empirically defining intersectoral agency is often based on a reference to the self-perceived group and organisational identifications [

54] and thereby their perceived organisational roles. Organisational roles can be understood as patterns of behaviour of all persons in a functional relationship, and thus the organisation as a system of roles [

55]. Acting in an organisational role involves reacting to others’ expectations but also convincing others to have certain expectations. When succeeding in this role, the role-player or agent obtains a positive response based on their actions [

56]. In our material, two variables are of interest: (a) to what degree do you think it is important to be a strategic and cross-sectoral planner? and (b) to what degree do you rate your influence on the municipality’s public health work? Both variables were scored from 0 (nothing at all) to 6 (a very large degree) (

Table 1). The two variables were added, giving an ordinal variable with a potential range from 0 to 12 and named ‘intersectoral agency’.

We thus understand that perceived organisational influence, together with having a role as a strategic planner, is to be understood as perceived intersectoral agency. In accordance with the literature, we assume that PHCs who act as intersectoral agents work in municipalities with differing contexts [

57], comprise certain individual characteristics [

35,

36,

38,

39,

40] but also meet barriers and opportunities within an organisation [

42,

44,

46,

52]. In other words, the degree of agency can be dependent upon the structured context within which they operate [

58]. In this setting, a PHC taking the role of an intersectoral boundary spanner may need support from management to gain formal authority, legitimacy and influence within the administration. We also aim to explore if self-reported intersectoral agency is associated with the ability to affect policy documents and social equality in local politics.

See

Table 1 for a list of all included variables and response categories.

Table 1.

Included variables and response categories.

Table 1.

Included variables and response categories.

| | Variable | Question | Response Categories |

|---|

| Individual characteristics | Gender | Gender | Male/female |

| Age | Age (specify age in years) | Metric |

| Years of education | How many years formal education do you have beyond high school (all courses, education, further education and more)? Combine part-time education to years. | Metric |

| Years employed | How long have you been employed in the municipality? (number of years) | Metric |

| Organisational factors | CEO closest manager | CEO your closest manager? | Yes/no |

| Level of position | Organizational level of position? | Manager/senior advisor/advisor/other |

| Percentage PH-work | Percentage of position of working with public health? | Metric, percent |

| Job-description | Written job-description? | Yes/no |

| Minicipal context | Population size | Registry data | Metric |

| Centrality | Registry data | Metric, range 0–1000 |

| Gini-coefficient | Registry data | Metric |

| Unemployment rate | Registry data | Metric, percent |

| | Social equality in politics | Is equitable allocation of resources a priority in the political process? | no/do not know = 0, yes = 1 |

| | Public health in budget | To what degree is public health a part of the economy plan or budget? | Likert-scale ranging from 0 = Not at all to 6 = to a very large degree |

| | Strategic role | To what degree do you think it is important to be a strategic and cross-sectional planner? | Likert-scale ranging from 0 = Not at all 6 = to a very large degree |

| | Perceived influence | To what degree do you rate your influence on the municipalitys’ public health work? | Likert-scale ranging from 0 = Nothing at all to 6 = to a very large degree |

| | Intersectorial Agences | Adding values of strategic role and perceived influence, and transformed to 0–12 | Ordinal |

2.2. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 25 and the AMOS engine v. 25. The threshold for statistical significance was set to a two-sided p < 0.05. Descriptive data are presented as n (percent) or mean (standard deviation). Following the degree of normality of variables, data were analysed through correlation analyses calculating Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Hypotheses 1–3 on factors affecting intersectoral agency were first tested through multiple linear regression analysis and hierarchical regression modelling, with the degree of intersectoral focus as dependent. Missing values are of importance in statistics as the sample shrinks when some of the respondents have missing values on some of the variables included in the regression model. We have controlled for differences between participants included in the regression analyses and those that were excluded due to missing values on one or more of the variables in the model. We found that those who were excluded from the analyses were younger (mean age 42 years) compared to those who were included (mean age 49 years). Otherwise, there were no differences in regard to municipal, personal and organisational characteristics between the two groups (see

Table 2). Since missing values were not calculated and imputed into the data set, we used BCA accelerated bootstrap sampling with 1000 samples in our regression analyses to calculate confidence intervals aimed to represent the population [

59].

We report bootstrap corrected values on unstandardised (95% CI) coefficients and p-values. In addition, we present standardised coefficients and squared part correlation values (not bootstrapped) as a proxy for explained variance in percentages for each single variable.

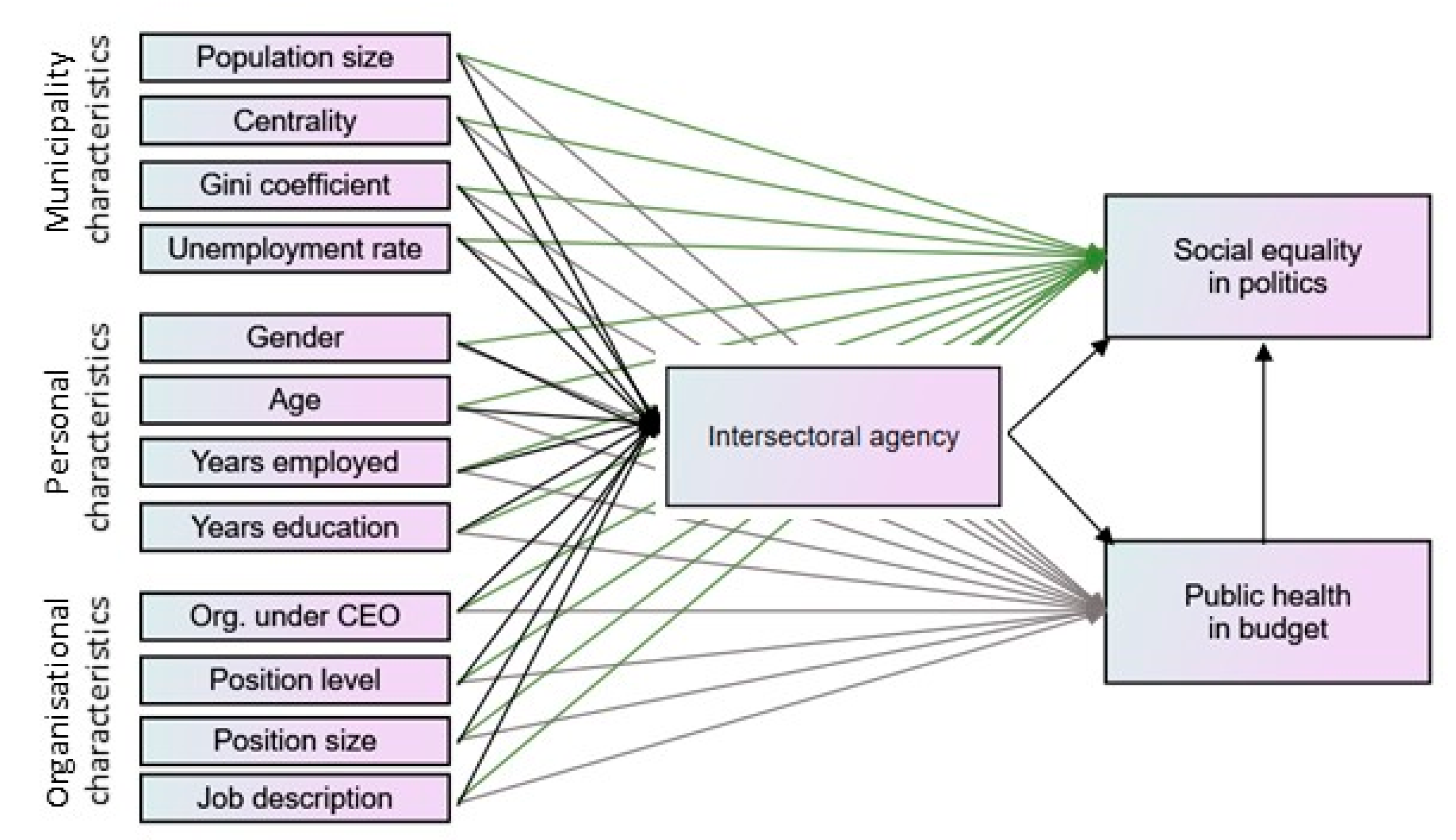

In the hierarchical regression model, three levels of independent variables were included. The first level, as a control level, contained variables describing the contextuality of municipalities (population size, centrality, Gini coefficient and unemployment). The second level was on individual characteristics (gender, age, municipal experience and length of education). The third level contained organisational factors (position in hierarchy, type of position, position size and job description). We present explained variance (R-squared) and adjusted explained variance for each of the three levels and unstandardised and standardised coefficients for each single variable in the model.

The fourth hypothesis on intersectoral agency affecting budgeting and social equality in politics was tested through path analyses through the AMOS engine v. 25. We included all variables (

Table 1) in the path model (

Figure 1). Error terms were fitted to all variables and full information maximum likelihood estimation of missing values was performed in the analyses, resulting in analysis of a full dataset (

n = 256). The final path model was developed after testing all possible pathways between all variables (

Table 1) in the model until the model fit the data. Multiple models were tested, and non-significant paths were removed from the model, until satisfactory model fit was achieved. The model fit was determined by examining the chi-square (χ

2), comparative fit index (CFI), the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Tucker–Lewis coefficient (TLI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The standardised regression coefficients (

ρ) and

p-values are presented in the diagram on each significant pathway.

3. Results

As shown in

Table 2, most participants were female, and they had a relatively long employment history with a mean of nearly 15 years. Mean age was 46 years, and education length, when combining all forms of education, was also quite long, with a mean of 6.5 years.

A little under one-third (30.5%) of the participants were organised at the municipality’s top level, reporting to the CEO. Approximately one-third (34.3%) of the participants had a position classified as an operative (e.g., not a purely administrative function). One-third (35.4%) of the participants had a job description concerning work in public health. Most participants had a part-time engagement in public health work with a mean position size of 46%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants.

| Gender (Females), n (%) | 166 | (80.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.2 | (11.1) |

| Years total education, mean (SD) | 6.5 | (2.9) |

| Years employed, mean (SD) | 14.7 | (10.0) |

| Organised under CEO, n (%) | 72 | (30.5) |

| Level of main position, n (%) | | |

| Manager | 59 | (23.2) |

| Special Advisor | 55 | (23.2) |

| Advisor | 53 | (20.9) |

| Other | 87 | (34.3) |

| Job-description, n (%) | 91 | (35.4) |

| Position size as PHC, mean (SD) | 48 | (33.6) |

| Population size, mean (SD) | 14,246 | (26,923) |

| Centrality index a, mean (SD) | 679 | (139) |

| Gini coefficient b, mean (SD) | 0.22 | (0.02) |

| Percentage unemployment, mean (SD) | 1.90 | (0.79) |

| Social equality in politics, yes, n (%) | 60 | (25.6) |

| Public health in budget, n (%) | | |

| Small degree | 76 | (36.4) |

| Moderate degree | 83 | (39.7) |

| Large degree | 50 | (23.9) |

| Strategic role, n (%) | | |

| Small degree | 57 | (25.9) |

| Moderate degree | 77 | (35.0) |

| Large degree | 86 | (39.1) |

| Perceived influence, n (%) | | |

| Small degree | 14 | (6.8) |

| Moderate degree | 76 | (37.1) |

| Large degree | 115 | (56.1) |

| Intersectoral agency c, mean (SD) | 8.7 | (1.8) |

3.1. Correlation between Variables

In

Table 3 we see that gender, work experience (years employed) and unemployment rate are not significantly correlated with other variables.

3.2. Testing Hypotheses 1–3

As shown in

Table 4, the regression model showed a total explained variance of 23.7% (r

2 = 0.237) with mostly organisational factors statistically significant associated with changes in the dependent variable ‘intersectoral agency’, where a hierarchical organisation (under the CEO) alone accounts for 10.1% of the variation, position size alone accounts for 11.4% and job descriptions scored an explaining 6.0% of the variation in intersectoral agency.

To test Hypotheses 1–3, we also performed a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with three levels of possible predictor groups. As seen in

Table 5, the first and second levels containing variables on municipality context (population size, centrality, Gini coefficient and unemployment rate) and individual characteristics (gender, age, years employed and total years education) did not reach a level of statistical significance. By introducing variables describing organisational factors (organised under CEO, position level, position size as PHC and job description), the explained variance of the model increased by 24.2%, giving a total explained variance of 28.1% and an adjusted explained variance of 19.4%.

Based on this analysis, we reject Hypotheses 1 and 2, indicating that municipal context and individual characteristics are not associated with the degree of perceived intersectoral agency. We can, however, verify Hypothesis 3, that organisational factors are associated with the degree of intersectoral agency, indicating that the PHC reports that organisational factors are important to act as a boundary spanner or policy entrepreneur in local public health work.

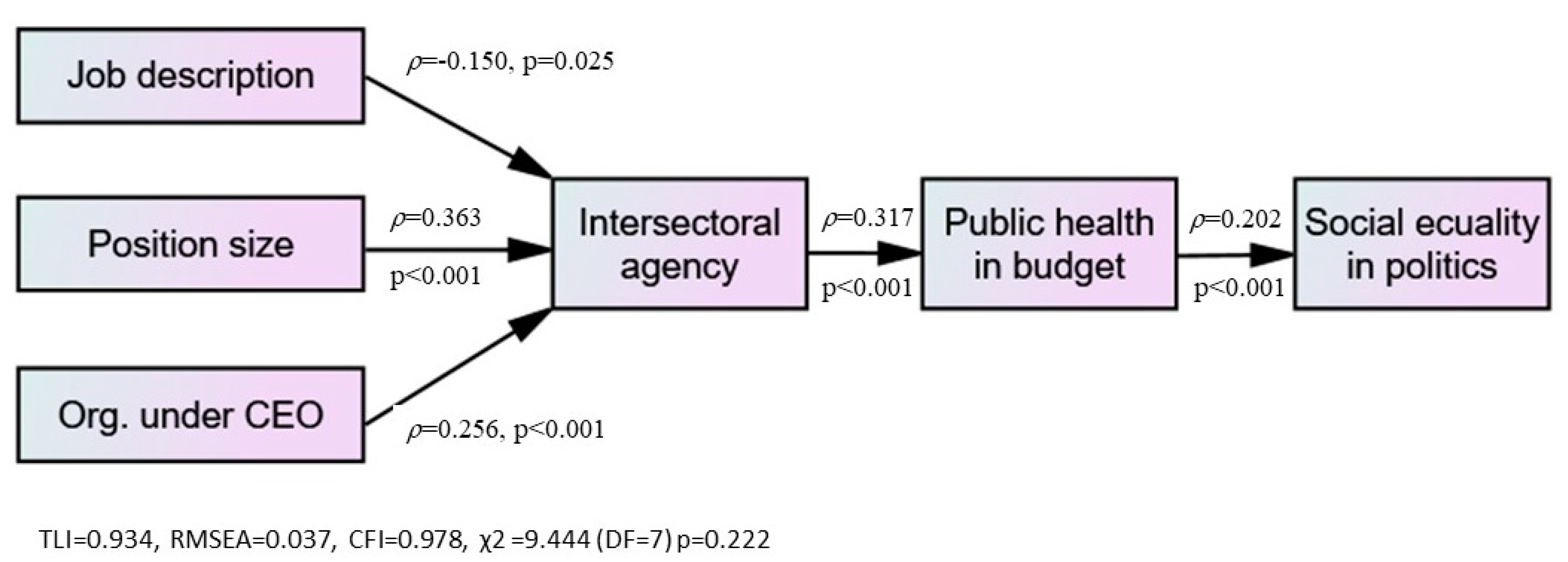

3.3. Testing Hypothesis 4

All relevant variables (

Table 1) were integrated into the path analysis (

Figure 1). After testing all possible paths between all included variables, model fit in the final model was rendered satisfactory, and we ended with a path model showing that organisational, but not individual or municipal, variables were significantly associated with the perceived role of intersectoral agency (

Table 6).

The perceived intersectoral agency was statistically and significantly associated with the notion of enabling public health in the budgets and, further, a statistically significant path between budget and the view of social equality in politics (non-significant pathways are not shown in

Figure 2).

It is noteworthy that the path analysis replicates the results from the multiple linear analyses performed earlier, showing that only three of the twelve independent variables (hierarchical organisation, job description and position size) were statistically and significantly associated with intersectoral agency. However, none of these variables were found to be directly associated with public health in the budget or experienced social equality in politics. We found a direct path between the degree of perceived intersectoral agency and the degree of public health in budgets/economy plans and, further, a direct path between the budget to the reported notion of social equality in politics.

However, as shown in

Table 7, the indirect effect of position size is not negligible in regard to reporting success in incorporating public health in budgets.

4. Discussion

In our material, neither individual nor municipal characteristics were associated with the PHCs’ notion of fair distribution in local policymaking. It is the organisational characteristics, the combination of position size and organisational placement in the hierarchy that relates to the PHCs’ perceived role and influence in local politics. We found that the major determinants of experienced intersectoral agency in municipal public health work were being in high positions in the organisational hierarchy, having formal job descriptions specifying tasks, expectations and responsibilities for their positions as PHCs, and being allowed and expected to execute public health coordination on a (near) full-time basis. We also found that PHCs who perceived themselves as intersectoral agents also reported being able to affect budgets and economy plans and thereby also policy outcomes. The indirect effect of organisational placement is significant but less significant than position size.

PHCs having a larger position size, organised into the highest organisational level under the CEO, seem to be crucial to PHCs’ perceived role and influence and thereby the possibility to integrate population health issues as a fair distribution and systematic HiAP approach into the municipal planning system. When a PHC is placed near the top level of the municipal administration and reports to the CEO, we presume that the PHC is expected to act intersectorally within a mandate from the CEO, or at least on behalf of the CEO in this matter. Taking the other stance, being organised lower in the organisational hierarchy, reporting to a section head and the mandate to operate intersectorally is, due to the organisational barriers, narrower. The top–down distribution of power remains important, at least when it comes to operating and coordinating between established sectors.

It may be reasonable to assume that if the municipalities prioritise public health, i.e., an HiAP approach, it is likely that the PHCs will be employed in larger positions and placed among the staff of the CEO. This can enable PHCs to take a strategic and coordinating role in the organisation and may increase their perceived influence on local policymaking. To fulfil intersectoral and interdisciplinary coordination, which is the essence of municipal public health work according to the Public Health Act [

14,

15], we found that PHCs located at the administrative top level had a higher statistical probability to report acting as intersectoral agents and acting as bureaucratic elite-level policy entrepreneurs [

40,

43,

44,

47]. In our analyses, we could not find significant associations between lower-level PHCs and the reporting of intersectoral agency, but we also could not exclude the possibility of PHCs acting as street-level policy entrepreneurs [

44,

45]. Addressing various types of entrepreneurships and how PHCs handle policy streams [

47] within other institutionalised policy arenas is an important and relevant avenue for further research and could provide important new insights about local intersectoral public health work.

A starting point for a discussion of elite-level public health policy entrepreneurs may be to assess the specific arena these public officials are staged in. Even though Arco Timmermans [

60] has studied decision-making and policy entrepreneurs in an international comparative setting, he distinguishes between different policy arenas that may be of interest in our case. Even small municipalities are considered as institutional arenas consisting of relatively stable structures and procedures containing conditions for access, jurisdictions and decision-making. In this view, policy entrepreneurs are rational and strategic actors and do not operate in a world of anarchy, where (in Kingdon’s terms) the problem stream, the politics stream and the policy stream are loosely coupled. Kingdon [

47] would probably argue that ‘windows of opportunities’ or ‘policy windows’ arise when the three streams coincide, and that the policy entrepreneur waits as a ‘pike in the reeds’ and grabs the opportunity when it shows itself.

Maybe most important, our findings support the notion that many PHCs themselves report that they play an essential role in prioritising public health issues in local policymaking. If PHCs perceive their influence as high and perceive their role as a strategic planner, local politicians may incorporate the consideration of fair distribution and social inequalities in health, both in the municipal finance plan and in local policymaking in general, both directly and indirectly.

In Norway, national policy initiatives concerning the HiAP approach are considerable. One example is the Norwegian Directorate of Health launched in 2018, a national guideline incorporating public health issues into the municipal planning system under the umbrella of HiAP [

1,

15]. As such, the PHCs are exposed to a collectivistic–integrative understanding of public health work [

19]. Previous research has shown how such national guidelines within the public health domain seem to function as a regulative and normative power for municipalities [

20,

60]. These means of governance are necessary but not sufficient instruments to achieve the whole-of-government approach needed to implement HiAP and promote equity. Our findings indicate that the municipalities that also use organisational design actively to support intersectoral agency are more likely to effectively address social inequality in health. To hire or appoint someone as public health coordinator is simply not enough; the position must be carefully designed to have any real impact on the implementation of a collectivist–integrative public health policy.

Limitations

This cross-sectional survey represents a snapshot of the situation as it manifested itself in 2019, and thus, we cannot assume any causality. The response rate was acceptable and highest in the most central and largest municipalities. The relatively low response rate from decentral and small-sized municipalities may result in a lower representation for these groups of municipalities. The inclusion of variables into the regression models was based on a theoretical approach and using other approaches may have led to other results. Maybe the most important limitation is that our analytic model is mostly based on self-reported data and not on objective observations of behaviour nor analyses of municipalities’ policy documents. Such measurements may have altered the conclusions of this study.