Abstract

Britain’s withdrawal of its EU membership has a number of political and economic implications for UK–EU relations. In seeking to understand the 2016 EU referendum outcome, it is insightful to study the historical development of discourses representing the UK–EU relationship. Doing so reveals the trends of British exceptionalism and British Euroscepticism as integral to these discourses. Applying a diachronic approach, this paper examines ten speeches by nine Conservative Prime Ministers (PMs) held at the annual Conservative Party Conferences from 1945 to 2020. The speeches include, among others, those by Winston Churchill, Margaret Thatcher, David Cameron and Boris Johnson. The qualitative analysis traces the discursive strategies employed by PMs in their construction of the Conservative narrative of national myth, focusing especially on the issues of British national identity in relation to Europe. Methods of Discourse Historical Analysis (DHA) and Critical Metaphor Analysis (CMA) are applied in order to identify strategies employed by PMs as tools of persuasion for the purpose of consolidating political power and promoting their policies. This study has identified three major interrelated strategies—myth, ally and enemy creation—which are used to narrate the story of Britain’s relationship with Europe as a potential member of the Union, as a member, and up to its efforts to leave the EU.

1. Introduction: A Mythical British Self versus a European Other

Brexit continues to have political and economic implications for UK–EU relations today. It is insightful to study the historical development of discourses employed in the representation of this relationship, specifically the conceptualisation of Europe’s role vis à vis Britain. Such a study allows for a deepened understanding of the context that was constitutive to the 2016 EU referendum outcome, which also has implications on this new stage in a relationship fraught with ambivalence.

There are two significant factors in the volatile nature of the relationship. The first is British exceptionalism—the self-perception on the part of the UK as a unique, special nation. Second is Euroscepticism—the tendency to harbour reservations about the supposed benefits of increased political cooperation between EU member states, which has been acknowledged as consistent in British EU discourse in the post-war era [1] (p. 162). As a result of these two factors, Britain has often been labelled a reluctant European, a state uncommitted to the European project. However, according to Jones [1] (p. 126), this label fails to acknowledge the existence of a British vision for Europe, specifically one oriented towards the Common Market. A tension results between these two visions for Europe, one desiring only economic cooperation and the other additionally seeking political cooperation. A perspective of these two visions as being incompatible and mutually exclusive raises the question of determining Europe’s role either as Britain’s friend or foe, a scenario which ultimately created the impetus for Brexit.

This diachronic study examines ten speeches by nine Conservative PMs held at the annual Conservative Party Conferences from 1945 to 2020. The Conservative Party was chosen as the subject of study as it was the party that led the UK into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 and back out of the EU in 2020. The annual leader’s speeches were chosen due to their function in terms of establishing shared values and consensus among the party members [2] (p. xiv). They are anticipated to make use of a range of discursive strategies of (de)legitimation through which the speakers position the Party as the solution to Britain’s problems and needs.

It is particularly important for ruling parties to establish the legitimacy of their leadership in order to maintain and even gain the power needed to enact their policies. Delegitimisation is an essential function of the persuasive speech employed by politicians [3]. Persuasion is a speech act in which one active party changes another passive party’s cognition by using language to get the audience to accept a point of view [4] (p. 6). As the medium of such persuasive speech, language is centrally involved in “power, and struggles for power” [5] (p. 53), wherefore political speeches are consistently analysed in order to identify the rhetorical strategies and devices they employ to this end. Charteris-Black [4] (p. 313) identifies four key rhetorical strategies for persuasion: the speaker’s ethical integrity and moral credibility, sounding right, demonstrating right thinking, and telling the right story. In order to posit themselves as Britain’s hero and leader and thus validate their claim to power, the Conservatives must first paint a convincing image of a Britain with which their audience can identify in order to gain their confidence. For this reason, this study traces the elements in the construction of the Conservative narrative of British national identity in relation to Europe.

The formation of national identity is closely tied to storytelling, namely that of a national myth or mythical nation. Myths are stories that provide explanations of worldly and otherworldly phenomena, such as the causes of good and evil, thereby serving as a useful tool in the construction of the notion of a Britain in need of Conservative leadership. Myths contribute to telling the right story by creating angels and demons and dramatising the struggle between them [4] (p. 22). This narrative representation is persuasive in that it frames intangible experiences in a manner that evokes an unconscious emotional response. Evoking emotion is desirable for political speech as it creates a basis on which the audience can evaluate the subject matter, effectively allowing the speaker to bypass other forms of reasoning to persuade the audience of their position [2] (p. 202). To prevent an abuse of power through linguistic manipulation, it is therefore important to discern the methods that can elicit such emotional appeal.

Specifically, this study examines the construction of this mythical British self in contrast to a European Other. Contrasting the self with an Other, a process known as ‘othering’, creates an implicit in-group whereby the ‘other’ out-group endangers that which is ‘ours’ by being ‘not us’ [6] (p. 1). As such, othering is an effective way of constructing a national identity, and rendering abstract values more tangible by presenting them in a relational context, since the self does not exist in isolation; indeed, acknowledgement of a difference is a prerequisite for the existence of any identity [7] (p. 15). Othering invites the audience (‘you’) into the ‘we’ narrative of nation, creating an emotional link between the two: for those who accept the invitation, “to become the ’you’ addressed by the narrative is to feel rage against those who threaten not only to take the ’benefits’ of the nation away, but also to destroy ’the nation’, which would signal the end of life itself” [6] (p. 12). While such a relation does not necessarily have to be one of friend/enemy, it is always possible for the relationship to become antagonistic when the ‘they’ is perceived to pose a threat to the identity and existence of the ‘we’ [7] (p. 15). In combination, the narrative of a mythical nation contrasted with an Other serves as a compelling vehicle to promote an ideology—institutional practices that are drawn upon unconsciously, legitimising existing power relations [5] (p. 64)—bringing individuals together under a shared group identity and world view united for a common purpose [4] (p. 22). Such ideological power to project assumptions or practices as ‘common sense’ is significant to this paper since it occurs through discourse [5].

This paper aims to analyse the discursive strategies employed by Conservative PMs in office between 1945 and 2020 and to identify their role in shaping British self-perception in relation to Europe and Britain’s role in the EU. In view of the consistency with which the Conservatives managed to hold the office of Prime Minister in the post-war era, their strategies are of interest for study relating to the gaining and maintaining of power in Britain.

2. Theoretical Framework: Combining DHA and CMA

This section introduces two critical approaches to discourse analysis employed in this study, namely Ruth Wodak’s [8] Discourse Historical Approach (DHA) and Jonathan Charteris-Black’s [9] Critical Metaphor Analysis (CMA), in order to determine linguistic strategies used by Conservative PMs in the formation of national identity.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a multidisciplinary approach that goes beyond merely describing discourse structures, but rather focuses on explaining them in relation to their contextual social and political issues [10] (p. 467). CDA is not a unitary theoretical framework, but rather comprises several methodological approaches related to discourse, cognition and society [10] (p. 467). Critique is “understood as gaining distance from the data, embedding the data in the social context, clarifying the political positioning of discourse participants, and having a focus on continuous self-reflection while undertaking research” [11] (p. 87). This critical perspective seeks to reveal how dominant social groups use discourse to legitimate and (re)produce power [10] (p. 467).

This study traces developments in discourse over time, wherefore it applies Wodak’s DHA, which considers the broader context of the speeches being analysed. By critically looking at the language used by those in power, DHA aims to ‘demystify’ the hegemony of certain discourses by determining their underlying ideologies [11] (p. 88). DHA recognises the intertextuality, the interrelationship between texts, “the transfer of main arguments from one text to the next” [11] (p. 90), and interdiscursivity, topic-related references to topics of other discourses within a discourse, as its object of study. As such, it views discourses as open and often hybrid, whereby the analysis of one discourse necessarily includes the consideration of other discourses. As a consequence, for this study, it is important to highlight that the Conservative discourse on Europe cannot be viewed entirely in isolation; instead, related discourses within the national-identity-forming discourse strategies of myth, ally and enemy creation are referred to where relevant.

DHA focuses on determining the strategies employed by its participants. As a form of argumentation, strategies refer to more or less intentionally planned practices that are employed in order to reach a “particular social, political, psychological or linguistic goal” [11] (p. 94). Central to identifying and tracing strategies over time are topoi, content-related ‘conclusion rules’ that connect arguments with claims [11] (p. 102). Since the concept of identity is context related and dynamic, identifying these argumentative patterns and their linguistic realisation—how they are explicitly expressed in language—is part of analysing macrostrategies used in national identity construction [12,13]. The analytical framework developed by Wodak et al. [8] (p. 3–4; emphasis added) comprises the following major hypotheses:

- (1)

- Nations are mental constructs perceived as discrete political entities by nationalised political subjects.

- (2)

- National identities are (re)produced discursively.

- (3)

- ‘National identity’ implies a complex of shared conceptions and perceptual schemata, as well as emotional dispositions, such as in-group members’ attitudes towards one another or towards members of an out-group.

- (4)

- Discursive constructs of national identities emphasise national uniqueness and intra-national uniformity, deemphasising intra-national differences.

- (5)

- There is no such thing as one national identity; rather, differing identities are discursively constructed in varying contexts.

These assumptions are important to keep in mind while analysing one specific construction of national identity, which, though tied to one particular party, is shaped by nine different PMs over a period of approximately 70 years, and which must be adaptable to changing circumstances. On a content level, the elements used to construct identity include a common history, territory, and culture. When applying these tools, one must therefore take into consideration the historical and cultural features of the nation in question [8] (p. 5), which is why this paper also includes a section on the historical context of the speeches (see Section 4). In this way, DHA helps to trace developments in the narrative of Britain’s relationship with Europe as a potential member of the EU, as a member and up to its efforts to leave the Union.

Charteris-Black’s [9] CMA serves as a further basis for identifying persuasive strategies such as the use of rhetoric devices like metaphors, personification and antitheses. His approach focuses particularly on metaphor due to its use in politics as a powerful means of persuasion [2,4]. Metaphors are often used in persuasive communication as a ‘long-term investment’, as their regular use establishes mental frameworks and thus “permits the creation of common ground by appeal to a shared cultural frame” [14] (p. 3). The elimination of alternative points of view through the establishment of frameworks for understanding complex concepts facilitates the establishment of a common ground or reference point for those who are persuaded. As Charteris-Black [4] (p. 9) argues, metaphor is most persuasive when paired with other rhetorical devices, as their interplay “conceals the contribution of any single strategy, and this avoids alerting the audience to the fact that they are being persuaded”. His work extensively covers metaphors employed by British politicians, some of which will be also referred to in this study. Salient metaphors he has identified [4] and that can be expected to occur in the selected speeches include, but are not limited to, personification, journeys, light/darkness, family, landscape, weather, conflict, health, life/death, and slavery/freedom.

Rhetoric often creates uncritical followers; CMA therefore aims to raise awareness of such persuasive methods, contributing to informed political engagement within democracies through improved understanding of the language of leadership [4]. CMA seeks to expose the intentions and ideologies that underlie language use by identifying which metaphors are chosen and why by demonstrating how they contribute to political myths and to telling a story that sounds right—in this case, the story of an exceptional British nation. This study relies on existing analysis of rhetoric devices utilised by British Conservative PMs conducted by Charteris-Black [2,4,9] to determine the persuasive strategies employed in the narrative of British national identity in relation to Europe.

3. Corpus Data and Methodological Framework

This study takes a diachronic approach, analysing the leader’s speech given by each PM at the annual Conservative Party Conference since 1945. Held in October, the Conservative Party Conference is a four-day convention with events, receptions and speeches that allow its members, the press, and the public to become familiar with the party’s ideas and policies for the upcoming year. It culminates with the leader’s speech, which is held by the incumbent Leader of the Conservative Party [15]. Considering its role at an occasion designed to promote Conservative Party ideals, this speech was chosen as the context for examining the construction of the Conservative national myth and its development after WWII.

The PMs included are listed in Table 1. Alec Douglas-Home (1963–1964) was excluded as he only held office for one year and held no leader’s speech. An adjustment was made in the case of Winston Churchill (1940–1945; 1950–1955), whose leader’s speeches were removed from the archives for copyright reasons and were therefore not fully accessible. Excerpts of his leader’s speeches found in compilations of his speeches are used in place of a complete speech. Two speeches were allocated to Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990), who held the office of Prime Minister for 11 years and whose speeches display a significant shift in tone from the beginning to the end of her service, which is relevant for the purpose of this study. As seen in Table 1, the corpus comprises ten speeches by nine Conservative PMs. It is also worth mentioning that different speeches reflect different domestic and international ‘crises’ and thus different conceptualisations of Europe that fit those narratives. Certainly, in Heath’s (1973) [16] and May’s (2018) [17] speeches the EU is a more prominent topic given the debate around entering and leaving the EU, correspondingly.

Table 1.

Corpus Data.

First, all speeches underwent a close reading in order to detect recurring themes related to the construction of national identity. The representation of the UK–EU relationship was chosen as a focus for closer examination. This topic was chosen as it was the Conservative Party who led the UK into the EEC in 1973 and back out of the EU in 2020, allowing an insightful analysis of attitudes towards Europe and UK’s membership of the EU. Next, the sections of the speeches discussing UK–EU relations were extracted for the purpose of conducting a further, more comprehensive study of the construction of British identity within this discourse. These excerpts were then analysed for any recurring themes and rhetorical devices employed in the representation of British vis à vis European identity. Passages displaying similar recurrent themes were grouped together as a basis for further categorisation and to infer connections and patterns within and between not only the topics but also the speeches, since a diachronic study of Party discourse also assumes intertextuality.

The analysis yielded three key interrelated discursive strategies or topoi, which were in turn further examined for relevant actors, themes and linguistic realisations, and to determine which of these were characteristically employed by which PM. It is important to mention that due to the overlap of patterns characteristic of interdiscursivity, it is not possible to isolate a ‘European discourse’; rather, it is necessary to consider the treatment of Europe within the context of other complementary discourses in order to draw comparative conclusions. Furthermore, this analysis considers prior knowledge of discursive strategies frequently employed in other discourses related to Europe [18,19,20,21,22]. In addition to socio-historic context, these studies provide the basis for recognising and identifying the linguistic features of populist rhetoric that is characteristic of the specific discourses and politicians under analysis.

4. Historical Development of UK–EU Relations

This section provides a brief historical overview, covering the most relevant stages of UK–EU relations, which provides some background for the subsequent speech analysis.

During its membership of the EU, Britain was often considered a “reluctant European”, due to its tendency to opt out of policies, which some felt demonstrated a lack of commitment. Jones [1] suggests that this label was not entirely accurate considering the fact that Britain did pursue a vision for Europe. Even before the end of WWII, Churchill supported the creation of a structure that would resemble a “United States of Europe”; however, he conceived of the UK as separate from this matter of continental affairs, claiming to be “with Europe, but not of it” [23]. Though invited, Britain initially declined membership and was thus not involved in the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, nor in its subsequent iteration, the European Economic Community (EEC) [1] (p. 13).

The UK began talks to join the EEC in 1961, which were motivated by a desire to keep up with the economic recovery being enjoyed by continental Europe [1] (p. 17). The UK’s first two membership applications in 1963 and 1967 were vetoed by the French President Charles de Gaulle, who considered Britain to be fundamentally incompatible with Europe. This sentiment was grounded in the UK’s “special relationship” with the US, which he believed rendered Britain a “Trojan horse” that could be used by the US to meddle in European affairs, and differences in both countries’ respective agricultural production, which he perceived as a potential economic threat to France [1] (p. 222).

Once de Gaulle was no longer president, a third membership application was successfully submitted under Conservative PM Edward Heath (1970–1974). Attitudes regarding Britain’s EEC membership had changed, especially as the British economy was ailing, and British industry leaders increasingly advocated

investment, collaboration and coordinated industrial policy in the hope of achieving economic recovery that was being exprerienced in Europe [24] (p. 319). The Treaty of Accession was signed in 1972 and came into effect on 1 January 1973. However, Harold Wilson’s Labour Party (1974–1976) ran on a platform to renegotiate the terms of Britain’s membership and to hold a subsequent referendum based on these terms, resulting in the first national referendum regarding EEC membership in 1975 [24]. Though the major political parties and mainstream press supported continued membership, there were significant divides within the Labour Party. Instead of the tradition of “collective responsibility”, where cabinet members are required to support the government’s chosen policy position, members of the Government were allowed to present their own views [1] (p. 17). The outcome of the referendum was a substantial majority in favour of continued membership. When the Labour Party later campaigned on a commitment to withdraw from the EEC without a referendum in 1983, the move was heavily defeated, and the party subsequently changed its policy toward the EEC.

Despite the favourable outcome, the UK developed its reputation as a reluctant European due to occasional policy disputes and its regular decision to opt out of EU legislation and policies. Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990) negotiated a rebate of British membership payments in 1984, and although she ratified the Single European Act (SEA) in 1987, her tone became increasingly Eurosceptic, as she warned against increased dominance from Brussels [1] (p. 20). Thatcher had promoted and even claimed credit for the framing of the SEA; she considered it the realisation of Britain’s free-trade vision for Europe, and seemingly ignored the political implications of references to a future EU and a common currency, which were controversial in her Conservative Party [1] (p. 29). Ultimately, the Maastricht Treaty transformed the European Community into the European Union and was ratified by Thatcher’s successor John Major (1990–1997) in 1992. The new name reflected the evolution from an economic to a political union, thereby appearing less like the inter-governmental organisation Thatcher and other Conservatives approved of and more like a supranational organisation, which they feared could lead to a federal European superstate [1] (p. 110). This development gave Eurosceptics further traction, contributing to the formation of both the Referendum Party and the UK Independence Party (UKIP). The Treaty of Lisbon was later approved and ratified in 2007 under Gordon Brown’s Labour Government (2007–2010), bringing further changes to the EU treaties.

David Cameron’s Conservative Party (2010–2016) won the 2015 general election on a platform that included a commitment to holding an in-out referendum regarding the UK–EU relationship, following further renegotiations in the winter of 2015 to 2016 [24] (p. 319). Debates and campaigns both for “Remain” and “Leave” focused on matters of trade and the European Single Market, security, migration and sovereignty. The government officially supported the “Remain” position for the referendum held on 23 June 2016, but, as was the case in 1975, ministers were allowed to campaign on either side. The result was in favour of leaving the EU, with “Leave” receiving 51.9% of votes [25]. Cameron subsequently resigned, to be succeeded by Theresa May, who had supported remaining and took on the role of “reluctant populist” [21]. She triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty in March of 2017, giving the UK and the EU two years to agree an exit deal. Brexit negotiations included both a withdrawal agreement and a trade agreement. After twice postponing the deadline upon not reaching an agreement, May also resigned in 2019. She was replaced by Boris Johnson, who had campaigned for “Leave” and considered the vote in favour of Brexit an “independence day” for Britain. He extended the deadline once more, and both the EU and UK parliaments ratified the withdrawal agreement on 31 January 2020, launching a transition period that concluded with the expiry of 31 December 2020.

When one observes the progression of the UK’s relationship with the EU and its predecessors, it becomes evident that respective perspectives regarding the purpose of the Union differed considerably, resulting in constant strain from the onset. Britain’s motives for European integration were economic—a pragmatic foreign policy for market access to enable economic growth without a commitment to a European ideal of a closer political union. Even while support for membership remained consistently high, arguments in favour of the EU focused more on economic benefit and less on a shared European identity. As EU developments increasingly contradicted the vision of British Eurosceptics, their nationalistic narrative posited Europe as an Other that restricted the realisation of Britain’s great global potential.

5. Analysis and Discussions

5.1. Discursive Strategies of National Identity

The following discussion is conducted in line with DHA as it provides a diachronic qualitative analysis of how the British Conservatives have systematically employed interrelated strategies over time in order to legitimise their power. A close reading of the speeches in question yielded several recurring themes creating the Conservative idea of British identity; special attention was paid to the central notions of DHA, namely intertextual and interdiscursive relationships between the speeches. As Wodak [13] states: “The DHA is three-dimensional: after (1) having identified the specific contents or topics of a specific discourse, (2) discursive strategies are investigated. Then, (3) linguistic means are examined as types, and the specific, context-dependent linguistic realizations are examined as tokens” (p. 4).

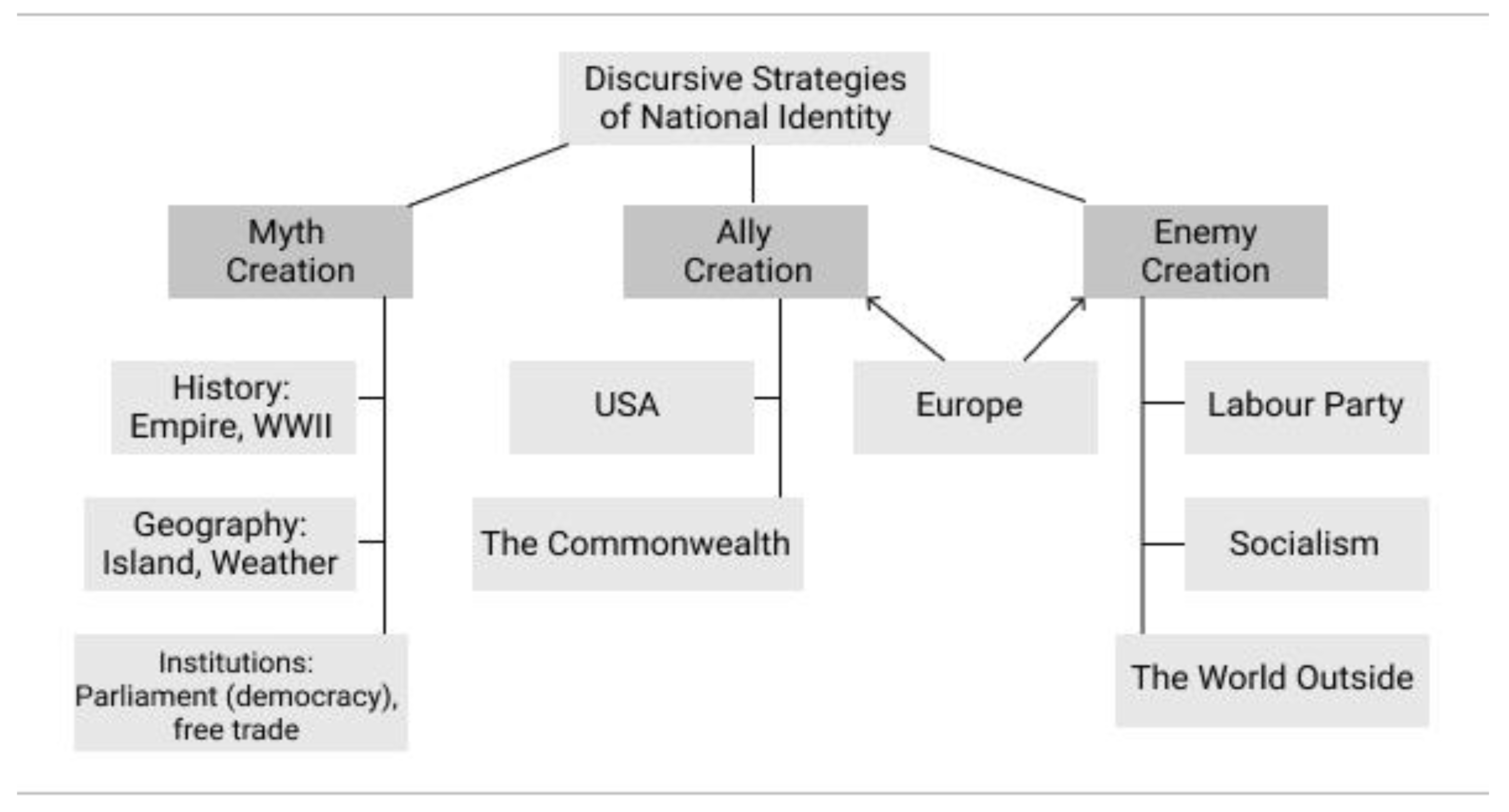

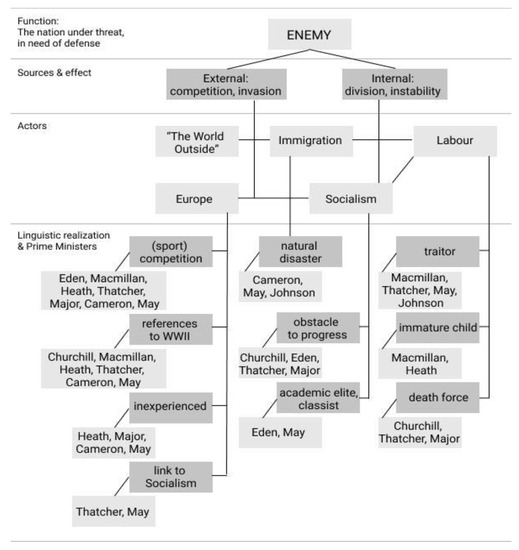

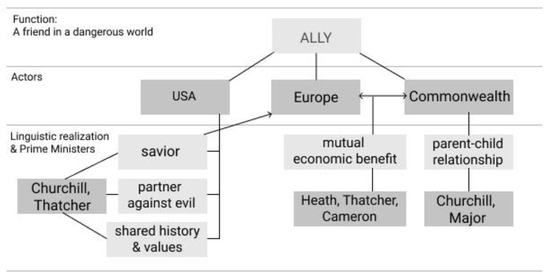

In our case, related themes were first grouped together in order to determine three primary discursive strategies or topoi of identity-constructing discourse, as displayed in Figure 1. The further analysis explores specific linguistic realisations and determines which of these were characteristically employed by which PM (cf. Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Discursive Strategies of National Identity.

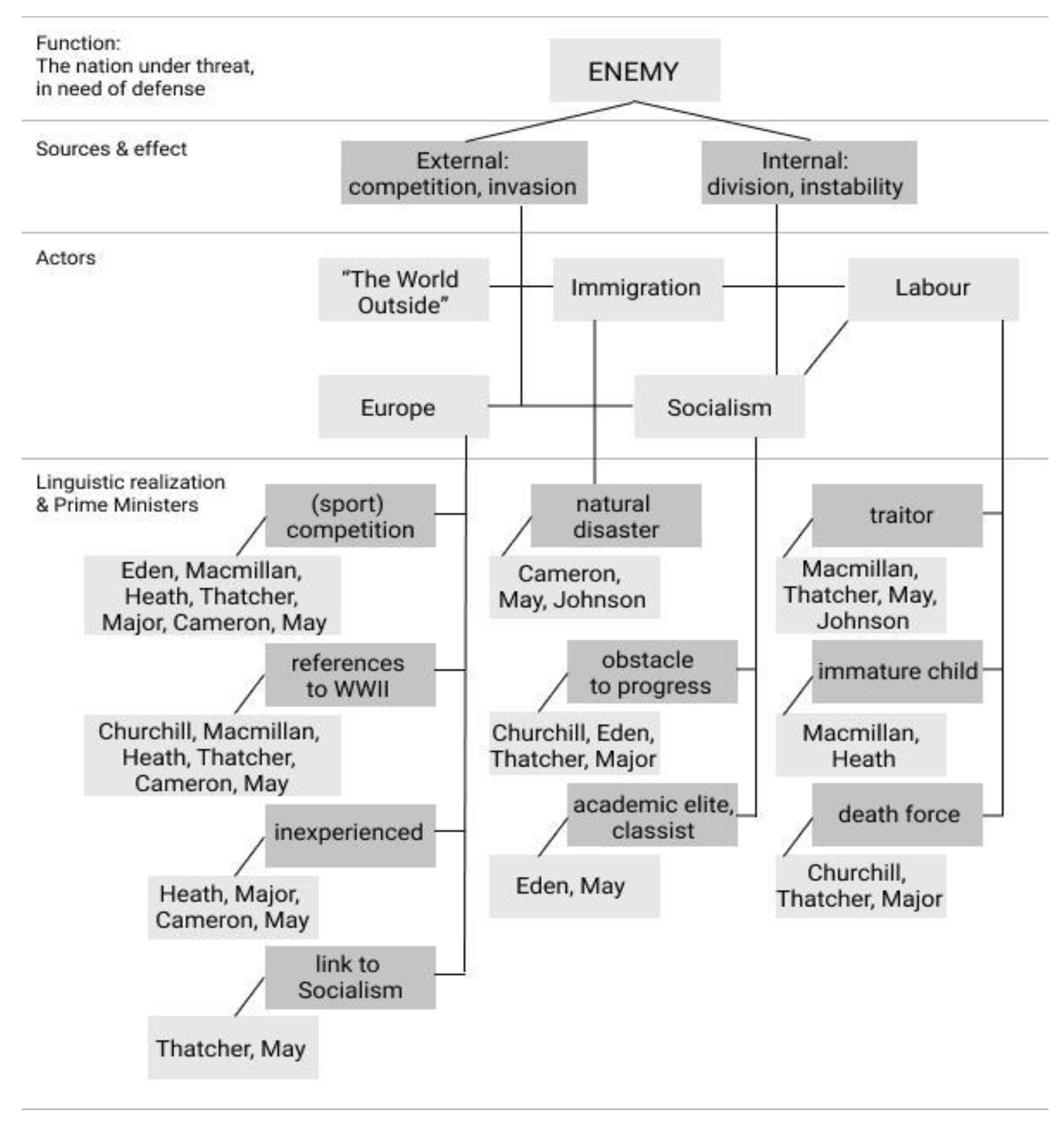

Figure 2.

Discursive Strategy of Enemy Creation.

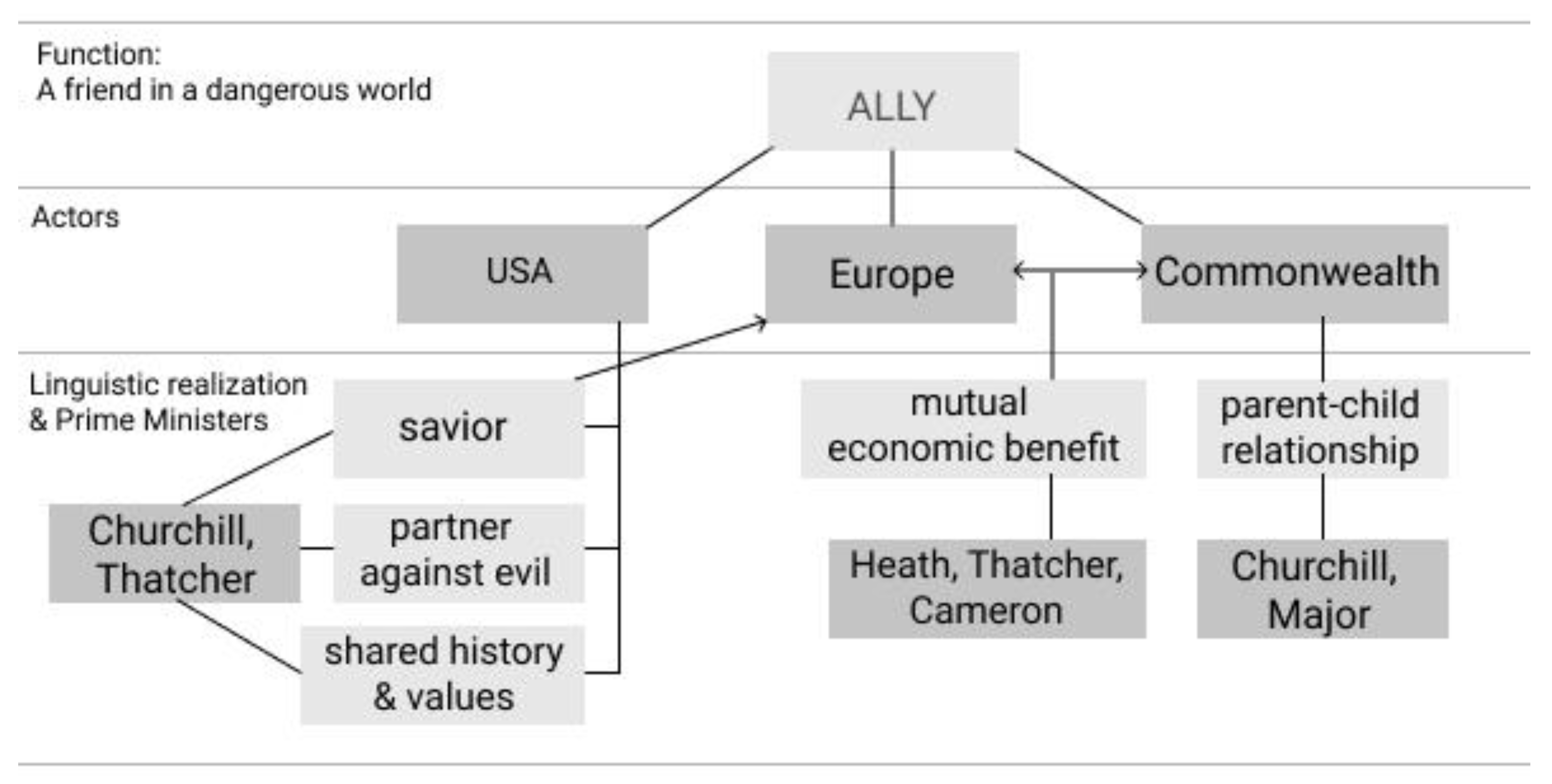

Figure 3.

Discursive Strategy of Ally Creation.

The three strategies are myth creation, ally creation and enemy creation. There is some overlap between the strategies as they are closely interconnected: the need for an ally arises from the existence of an enemy, whose threat in turn heightens the emotional appeal of loyalty to the mythical nation. Core content-level areas of national identity-construction include a collective past, a common culture and common territory [8] (p. 4). In the case of Britain, the collective past expresses itself in references to the glory days of the British Empire’s global influence and the victory over fascism in WWII. Regarding common culture, emphasis is placed on the British Parliament and democracy, while the common territory is the British Isles and their climate.

- (1)

- We are an island race. That is an accident of geography. But it is a fact that has shaped our history. It has also shaped our thinking. (Heath 1973; emphasis added) [16]

- (2)

- Our Parliament—the British Parliament—decided they shouldn’t have that right. This is the country that wrote Magna Carta…the country that time and again has stood up for human rights… whether liberating Europe from fascism or leading the charge today against sexual violence in war. Let me put this very clearly: We do not require instruction on this from judges in Strasbourg. (Cameron 2014; emphasis added) [26]

Allies such as the USA and the Commonwealth are required in a dangerous world in which, among other things, socialism threatens the tenets of democracy and free trade to which Conservative Britain holds fast in the face of a treacherous Labour Party.

- (3)

- We cannot defend ourselves, either in this island or in Europe, without a close, effective and warm-hearted alliance with the United States. Our friendship with America rests not only on the memory of common dangers jointly faced and of common ancestors. It rests on respect for the same rule of law and representative democracy. (Thatcher 1981; emphasis added) [27]

- (4)

- We have given birth to a whole family of nations. I never forget that as I contemplate our future role in Europe (Major 1996; emphasis added) [28]

As demonstrated in Figure 1, Europe features in both discursive strategies, which raises the question of whether Europe is Britain’s friend or foe. It is the relationship between this question and the issue of British national identity that will be further analysed in what follows. Guiding questions in this respect look at the circumstances in which Europe is posited as either friend or foe, what function this role plays with regard to creating the desired mode of British self-awareness, and how the respective representations are realised in language. To this end, Figure 2 and Figure 3 take a closer look at the enemy and ally creation strategies before delving into the portrayal of Europe.

5.2. Enemy Creation Strategy

Beginning with the enemy creation strategy, oppositional relationships serve to define the Conservative Party through contrasting it with that which it is not. After all, “to exist is to be called into being in relation to an Otherness” [29] (p. xvi). The creation of “a conspiratorial enemy and a suffering people who should be rescued by a hero” [4] (p. 327; emphasis added) is part of telling the right story. They create a sense of threat to the nation as it is portrayed and allow the Conservative Party to present itself as the hero ready to stand up in defence of Britain, as evidenced, for example, by Cameron [26] who proclaimed he would “go to Brussels [to] get what Britain needs”.

Britain’s needs are threatened from both within and without, whereby internal threat creates a sense of division and instability. External threat creates the need to compete with the outside world to safeguard the economic and political means needed to maintain a British way of life, as well as to guard against invasions and thus prevent changes to British society. As Figure 2 demonstrates, Europe shares ties to several threat sources, which will be discussed briefly as they relate to Europe in order to provide a more holistic understanding of the interconnected dynamics within this strategy.

The Labour Party is consistently presented as a traitor to Great Britain, alternatively as “the ‘get out’ party” (Thatcher 1981) [27] at a time during which Common Market membership was deemed favourable, or as a party willing to sell Britain out by accepting any Brexit deal:

- (5)

- We have a Labour Party that, if they were in Government, would accept any deal the EU chose to offer, regardless of how bad it is for the UK. (May 2018; emphasis added) [17]

- (6)

- We believe passionately in our wonderful Union, our United Kingdom–while the Labour opposition who have done frankly nothing to defend the Union, and continue to flirt with those who would tear our country apart. (Johnson 2020; emphasis added) [30]

Either way, Labour is portrayed as acting in its own political interest rather than the national interest. Furthermore, the Labour Party is represented as an immature child, “sulking at a distance” (Heath 1973) [16] and expressing discontentment with “feeble blustering” [16] when things do not go its way. Charteris-Black [4] (p. 41) has proposed the conceptual metaphor labour is a death force, which contrasts with conservatives are a life force, based on his study of Conservative politicians’ speeches. This observation holds true among the selected speeches, in which the Labour Party is blamed for inflicting “drab disheartenment and frustration” on the British nation (Churchill 1946) [31] and is accused of promoting policies—such as the suggestion of leaving the EU—that would force “a million more to join the dole queues” (Thatcher 1981) [27]. As Labour was previously called the Socialist Party [31], it is naturally linked to the threat of socialism.

Socialism as a political ideology is tied both to internal threat in the form of political organisations such as the Labour Party, as well as to an ideological threat on a global scale. Within the context of the Cold War, the Conservative Party presents socialism as a threat to democracy and free markets and thus as an obstacle to progress which has “become a gallop instead of a trot” (Eden 1956) [32], leaving socialist doctrine behind. It is further presented as an academic and theoretical exercise, not grounded in the reality of the working class, but rather an experiment of the elite, demonstrating the early tenets of a perceived struggle against an elite class, which is prevalent in the populist rhetoric observed in modern discourse pertaining to Brexit [21]. Considering the international political context directly after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, Thatcher’s (1990) [33] statement concerning further EU integration that “intervention, centralisation and lack of accountability may appeal to Socialists“ is significant in that it posits such efforts as counter to the victory in 1989 of the ‘Free World’ over Communism. Although socialism becomes a less explicit threat after the Cold War, allusions to it remain emotionally evocative due to the well-established discourse of it as an enemy. This frame set by Thatcher is echoed in May’s statement in a defence of free markets right after outlining Brexit as a moment of opportunity for Britain.

- (7)

- Closed markets and command economies were not overthrown by powerful elites, but by ordinary people (May 2018; emphasis added) [17]

May’s statement implies that the EU does not serve the needs of regular British people. References to the British people were also frequent in the right-wing press, especially in the context of discussing the will, wish, verdict, or decision of the British people as a reference to the 2016 EU referendum outcome [20]. With regard to the British people, such a label raises the question of who does and does not belong, and leads to the issue of immigration as a perceived threat from the time of Cameron’s leadership on. European migration actually became a controversial issue under a Labour government (1997–2010). The Conservatives and the right-wing press consistently emphasised that the number of EU migrants coming to the UK under the Labour government was excessive [34,35], using linguistic patterns like open borders to a huge influx of migrant workers, let in too many—a technique known as quantification [36,37]. The related metaphor in reference to excessive migration is that of a flood, an uncontrollable natural disaster wreaking havoc on the nation [14,38,39]. “The metaphorical transfer from the source domain of natural disasters onto the target domain of migratory movements can […] elicit the feeling that migration is dangerous and excessive” [35] (p. 69).

- (8)

- Numbers that have increased faster than we in this country wanted…at a level that was too much for our communities, for our labour markets (Cameron 2014; emphasis added) [26]

Both in political and media discourses, the arrival of EU citizens is often portrayed as an unwanted invasion by external forces (threat) causing internal instability and putting pressure and burden on the British welfare system [35] (p. 72). Moreover, EU citizens are systematically misrecognised in these discourses, as they are grouped with non-EU migrants rather than recognised as fellow citizens [40] (p. 3).

Figure 2 is not able to provide much detail regarding the outside world due to space constraints. It is worth noting, however, that the world is consistently depicted as a place of danger (Thatcher 1981) [27], a field on which Britain must earn its place (Macmillan 1961, Heath 1973) [16,41] because others have forgotten its many accomplishments (Thatcher 1981) [27]. These expressions are systematically used by British Conservative PMs in order to create a powerful discourse of fear. DHA considers topos of threat as one of the key topoi as its systematic use leads to the fact that the general public turns to and accepts state control to protect them. Considering the hostility with which the outside world is depicted, the extent to which Britain is seen to be part of Europe plays a role in its depiction as friend or foe. Before delving into the portrayal of Europe, we will next consider the discursive strategy of ally creation.

5.3. Ally Creation Strategy

A dangerous world filled with enemies can require the presence of allies who can help fight for one’s interests. Churchill [42] proposed ‘three great circles’ linked by Britain’s presence in each domain: the Commonwealth, the English-speaking world, and a United Europe—in that order of importance. As Britain’s former empire, the Commonwealth is less an ally and more of an investment or resource. Their relationship is presented as that of a parent and its child, in which, with “the ward grown up and able to arrange his own affairs, the guardians can take their honourable discharge” (Macmillan 1961) [41].

These nations were raised by Britain during the stage of the British Empire and have now reached maturity; they have ventured out into the world, but remain members of a single family. The Commonwealth is prioritised insofar as it is part of Britain. However, among the selected speeches, it initially wanes in importance thematically as the independence movement progresses, and Britain is even positioned as a victim among the other Commonwealth members who are blamed for delaying Britain’s entry into the EEC because they failed to recognise earlier the resultant mutual economic benefit (Heath 1973) [16]. Its existence later serves as a counterweight to Europe, the ‘family of nations’ (Major 1996) [28] whom Britain birthed and with whom it remains connected. While nostalgia for the glory days when “Britannia [ruled] the waves” (Johnson 2020) [30] implicitly includes the Commonwealth nations in a euphemism for Empire [40,43], they cease to be explicitly mentioned in the analysed speeches.

The US “twice saved us this century” (Thatcher 1981) [27], though whether this ‘us’ refers to ‘this island’ or all of Europe, whose freedom the US enabled, is unclear. Interestingly, in the selected speeches, there is a gap between Churchill and Thatcher regarding to references of the US’s military aid in the world wars—only Heath [16] briefly mentions the US in the context of the EEC successfully agreeing on a joint policy towards this mutual ally. The two nations are usually personified and shown as sharing a warm-hearted friendship. In the US, the UK has found an equal partner in its global aspirations, always ready to step in when Britain needs aid.

The relationships with Commonwealth member states and the USA serve to posit Britain as an outward-looking global actor. When comparing Figure 2 and Figure 3, however, one can see a noticeable imbalance between the two strategies. The diagram for the enemy creation strategy is more extensive than that of ally creation, featuring a greater number of actors and linguistic realisations. It is also consistently employed in one form or another by each PM included in this study, which is not the case for ally creation, though this may be the result of the data available from the limited amount of speeches examined. Either way, it is evident that the notion of the presence of enemies is heavily relied on in the construction and defence of an exceptional British nation, and there even appears to be a certain reluctance to rely on aid unless absolutely necessary. Such a framework understandably has implications for Europe’s potential as ally or enemy.

5.4. Europe: Friend or Foe?

Together, the strategies of enemy and ally creation work to foster an image of (Conservative) Britain as a force of good in the world, with Europe as either a complementary or oppositional force. They are employed strategically to alternately (de)legitimise the EU as a partner to the UK [44].

As expected when considering the historical development of the UK–EU relationship, there is a progression from neighbour to outsider among the speeches selected. The proportion of each speech dedicated to EU discourse also increases from the UK’s entry into the EEC under Heath [16] onward; it is especially prominent for May [17], whose entire two-year term was dedicated to the subject of negotiating a Brexit deal post-referendum. However, it hardly features in Johnson’s [30] speech, in which he envisions a Britain of the future in which its citizens wave ‘Brexit blue’ passports upon return to the isles. Part of the reason Europe hardly features in his speech may also have to do with the COVID-19 pandemic [45] (p. 165), which superseded the conclusion of the Brexit transition period in terms of urgency.

From Churchill through to Heath, the tone towards Europe is rather positive. After WWII, it is characterised by a sense of hopeful optimism that closer cooperation between European nations will help prevent a future war on European soil.

- (9)

- And it could be greatly to the advantage of this country and of the Commonwealth, if in commerce, and in other matters too, we in Western Europe could draw closer together and always practise joint policies as well as observe joint treaties. It is my hope that this community of interest and loyal friendship may one day find expression in some closer form of relationship between us (Eden 1956; emphasis added) [32]

From Churchill’s concept of a United States of Europe (not mentioned in the selected speeches), over Eden and Macmillan’s expressions of intent to forge a closer relationship both politically and economically, to Heath’s campaign to join the EEC, PMs employ a range of motifs to depict the desired relationship. For Eden and Heath, it takes the form of a business partnership, while Macmillan employs a journey metaphor:

- (10)

- I have spoken of Europe and of our hope that Britain may become more closely associated with Europe, economically and politically. We must think of Europe and the Commonwealth, not as rivals but as joint pilgrims on the road to peace and freedom. (Macmillan 1961; emphasis added) [41]

Although political cooperation is mentioned as being desirable, for example, in a common policy toward the US, the most frequent and concrete examples of membership benefits are economic, such as access to the Common Market and common economic policies. Furthermore, the partnership is framed as one in which the expertise of Britain, a nation with a rich political history (remember references to the British parliament discussed in Section 5.1), is essential in terms of ensuring the proper functioning of the joint institutions.

- (11)

- To have all our countries with their different histories, their traditional rivalries, sitting round the same table agreeing on a common purpose–that in itself in Copenhagen was a piece of history. But let there be no doubt about one thing. This success, this latest coming together of the nations of Europe, would not have been possible if Britain had not been a member of the European Community. (Heath 1973; emphasis added) [16]

- (12)

- Our Parliament has endured for 700 years and has been a beacon of hope to the peoples of Europe in their darkest days. Our aim is to see Europe become the greatest practical expression of political and economic liberty the world over. We will accept nothing less. (Thatcher 1990; emphasis added) [33]

Britain’s membership is portrayed as an opportunity for Britain to exert its influence and breathe life into the European project, which also resembles the parent-child dynamic extant in the relationship with the Commonwealth. Britain and Europe are thus not seen as equal partners; the highlighting of Britain’s potential as benevolent hero also downplays the significance of the economic support that membership provides.

This perceived power imbalance takes a turn from an opportunity to a threat once seeds of doubt are sown with regard to the future of the Union. The name change from the European Community to the European Union and consequential focus on political union can be attributed as a contributing factor in this shift. Although Thatcher initially considers the prospect of shirking membership responsibilities to be “a contemptible policy for Britain” [27], she later considers the proposal of a single currency as one that threatens national sovereignty by “entering a federal Europe through the back doors” [33]. Such a supranational organisation, she claims, would ignore and suppress the sense of nationhood of the sovereign states co-operating with one another, while its accompanying centralisation would only appeal to socialists, long-standing enemies of Conservative Britain. Her speeches are marked by antithesis, creating tension through contrast:

- (13)

- Nor do we see the Europe of the future as a tight little inward-looking protectionist group which would induce the rest of the world to form itself into similar blocs. We want a Europe which is outward looking, and open to all the countries of Europe once they are democratic and ready to join. (Thatcher 1990; emphasis added) [33]

Italicised are two contrasting visions of Europe: first a self-focused organisation that she calls a bloc, a term reminiscent of the recently-fallen Soviet Bloc and which thus evokes memories of the Cold War; this contrasts with the second vision in the latter’s appeal for democracy and openness both to potential European members and to global aspirations. In discussing the dangers of the outside world, she points to Europe’s past as an epicentre of war, and to the need for the US alliance to maintain peace and freedom on the continent (cf. Example 3). Thatcher’s rhetoric, characterised by the metaphor politics is conflict [4] (p. 169), casts doubt on the reliability of Europe as an ally, opening the path for the search for alternatives for Britain’s future. This sense of doubt and betrayal is also evident in subsequent speeches by Major, Cameron and May. Cameron [26] claims that the EU’s interpretations of its charters are “frankly wrong”, and suggests that the Conservative British interpretation is correct instead. While economic matters are consistently framed competitively, the tone shifts as the representation of Europe gradually shifts away from Britain’s inner circle. The stakes are raised from a sports match to a military quest.

- (14)

- We set out to create jobs. And we are succeeding. Unemployment is lower here than in any comparable country in Europe. In Britain it is falling. In Europe it is not. Last year, this year, and next year we are set to have higher growth here, in our country, than any big country in Europe […] The plain truth is, I am the first Prime Minister for generations who can say ‘We are the most competitive economy in Europe.’ (Major 1996; emphasis added) [28]

- (15)

- Around that table in Europe they know I say what I mean, and mean what I say. So we’re going to go in as a country, get our powers back, fight for our national interest…and yes–we’ll put it to a referendum… in or out–it will be your choice… and let the message go out from this hall: it is only with a Conservative Government that you will get that choice. (Cameron 2014; emphasis added) [26]

The desire to regain control refers not only to economic decisions, but also to those related to immigration from other EU member states [22]. EU citizens are misrepresented as migrants [40] (p. 3) in a discourse marked by uncertainty in the distinction between those who are welcome and those who are not. This difficulty causes anxiety, as “the possibility that we may not be able to tell the difference swiftly converts into the possibility that any of those incoming bodies may be bogus” [6] (p. 47). Citizens with the right to live and work in the UK thus become subject to dehumanising rhetoric that posits them as invading alien forces over which Britain must regain control [14,34,35,39]. Additionally, in the speeches of May and Johnson, a clear distinction is drawn between high-skilled and lower-skilled migrants; a similar discursive trend is reproduced in the right-wing press [35] (p. 103). Parnell [46] (p. 98) labels this tendency as “a neoliberal construction of migrant acceptability, in which highly skilled workers are valued […], while lower-skilled migrants are disparaged”.

- (16)

- And yes–we need controlled borders and an immigration system that puts the British people first […] But we know the bigger issue today is migration from within the EU. Immediate access to our welfare system. Paying benefits to families back home. (Cameron 2014; emphasis added) [26]

- (17)

- Throughout our history, migrants have made a huge contribution to our country–and they will continue to in the future. Those with the skills we need, who want to come here and work hard, will find a welcome. But we will be able to reduce the numbers, as we promised. (May 2020; emphasis added) [17]

References to Europe as a monolith contribute to shaping the perception of it as a foe because the perceived power imbalance posits Britain as a victim that must be defended. The only country that is occasionally singled out as economic competitor is Germany, also a former enemy. Simultaneous references to British ingenuity, to economic and political successes both past and present, as well as a shift towards other allies serve to portray Britain as “a stronger, mightier entity when no longer part of the EU” [20] (p. 8). This discourse is also (re)constructed in the right-wing British press [19,20]. This sets the scene for the argument for a renewed referendum on Britain’s EU membership.

With Britain’s referendum decision to leave the EU, Europe drifts further away from Britain. Although May [17] retrieves the business framework from the EEC membership negotiations of the past in her presentation of a ‘Brexit deal’, her language use creates a sense of distance from Britain’s neighbour. She is not the first to utilise populist rhetoric in discussing Europe, such as the notion of a struggle of the people against an elite group—Heath [16] had framed it as a community of and for the peoples of Europe, as opposed to one of governments. However, May turns this around, pitching “the British people” against the project of an elite, and calling plans for a second referendum a “politicians’ vote” that would deny the will of the people [20,21]. While the business metaphor initially appears to be constructive, May’s [17] discourse highlighting the virtues of the British people, such as “[sticking] together and [holding] our nerve” in a process that is “very challenging for the EU” furthers the perception that Britain is better off without Europe. Indeed, the idea of renewed EU membership in Johnson’s [30] speech becomes leverage against domestic traitors who “are secretly scheming to overturn Brexit and take us back into the EU”, threatening to undo what Britain has fought so hard to achieve. This delegitimisation of the EU as the UK’s partner effectively places Europe outside of Britain as part of an outside world in which Britain must fight for its rightful place.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

The creation and further adaptation of a national myth are a powerful strategy used by politicians to persuade their audience of the validity of their policies. Telling the right story entails employing devices to convince listeners of one’s arguments. This argumentation occurs not only on a content level, but also on a linguistic level through the use of rhetorical devices including, but not limited to, metaphor, personification and antithesis. The interplay between devices enhances the persuasive effect as it downplays the presence of the individual components [4] (p. 9). While most other studies focus on the rhetoric of individual politicians [4,21], this study examines the discourse of a single political party using a selection of speeches by its most influential members. A study of the historical development of discourses employed in the representation of the UK–EU relationship enables a deepened understanding of discourses leading up to the 2016 EU referendum outcome and the consequent parliamentary struggle over the institutionalisation of hard Brexit. This study seeks to do justice to such a broad topic while remaining within the scope of this paper by selecting only one speech per individual (for exceptions see Section 3). As such, our understanding of the results and findings could potentially be deepened by a study that compares not only individual speeches but rather corpora of the relevant politicians’ speeches. A study of the Labour Party’s discourse regarding Europe [44] is also of further interest, in order to compare it with the Conservative narrative. The Labour Party was the first to put EU membership to a referendum and later ran on a campaign to leave, before becoming comparatively associated with the pro-remain side of the 2016 referendum.

To conclude this study, let us summarise some of the key findings of the analysis. Of the three discursive strategies discerned, the first utilises the expected topics for national identity formation identified by Wodak et al. [8], namely common territory, history and culture. The other two centre on identification vis à vis an “Other,” of which one is amicable and the other antagonistic. Among these two, the latter is considerably more pronounced than the former, indicating that relations of enmity are more significant in Conservative discourse. Evidently, the topos of threat is systematically used in order to create a discourse of fear, which ultimately helps the Conservatives to consolidate their power and promote their policies. A discourse of fear creates the need for a heroic leader who can face challenges against all odds in order to stand up for the nation.

This study has shown that Europe straddles the two strategies of ally creation and enemy creation, causing consistent tension that is evident throughout the analysed speeches. As the political or economic need requires, these two strategies are alternatingly employed to (de)legitimise Europe as a partner to the UK. As such, the significance of British exceptionalism can be traced in the development of EU discourse where British contribution is consistently highlighted, while the benefits of membership are downplayed. The acknowledgement solely of economic benefits creates the impression that membership is considered “a pragmatic and utilitarian foreign policy stripped of a normative commitment to a European ideal of ever closer union” [47] (p. 8). Indeed, the acknowledgement of the EU partners as equals that are necessary for successful political cooperation undermines Britain’s claim to authority. The EU thus turns from an economic partner to a source of threat to British identity, and must therefore be removed from Britain’s inner circle in order to eliminate the tension it creates in terms of the telling of the narrative of the exceptional British nation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.I. and D.D.; methodology A.I. and D.D.; formal analysis, D.D.; resources, D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.; writing—review and editing, A.I.; visualisation, D.D.; supervision, A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All speeches are available at http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org and https://www.ukpol.co.uk.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones, A. Britain and the European Union, 2nd ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black, J. Analysing Political Speeches: Rhetoric, Discourse and Metaphor; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappettini, F.; Bennett, S. Reimagining Europe and its (dis)integration: (De)legitimising the EU’s project in times of crisis. J. Lang. Politics 2022, 21. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black, J. Politicians and Rhetoric: The Persuasive Power of Metaphor; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Power, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. The Cultural Politics of Emotion; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffe, C. On the Political; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R.; de Cillia, R.; Reisigl, M.; Liebhart, K. The Discursive Construction of National Identity, 2nd ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black, J. Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Dijk, T.A. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 2nd ed.; Schiffrin, D., Tannen, D., Hamilton, E., Eds.; Blackwell: London, UK, 2015; pp. 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisigl, M.; Wodak, R. The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In Methods for Critical Discourse Analysis; Wodak, R., Meyer, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zappettini, F. European Identities in Discourse: A Transnational Citizens’ Perspective; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. ‘We have the character of an island nation’: A discourse-historical analysis of David Cameron’s ‘Bloomberg speech’ on the European Union. In Discursivity, Performativity and Mediation in Political Discourse; European University Institute Working Paper; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 80, p. 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, C. Representing the Windrush Generation: Metaphor in Discourses Then and Now. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2020, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. At-a-Glance: Guide to Conservative 2016 Conference Agenda. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-37519563 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Heath, E. Leader’s Speech. 1973. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=120 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- May, T. ‘Speech to Conservative Party Conference’. 2018. Available online: https://www.ukpol.co.uk/theresa-may-2018-speech-to-conservative-party-conference/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Charteris-Black, J. Metaphors of Brexit: No Cherries on the Cake? Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islentyeva, A. The Europe of Scary Metaphors: The Voices of the British Right-Wing Press. Z. Für Angl. Und Am. 2019, 67, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islentyeva, A.; Abdel Kafi, M. Constructing National Identity in the British Press: The Britain vs. Europe Dichotomy. J. Corpora Discourse Stud. 2021, 4, 68–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowitsch, A. Delivering a Brexit Deal to the British People: Theresa May as a Reluctant Populist. Z. Für Angl. Und Am. 2019, 67, 231–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappettini, F. The Brexit referendum: How trade and immigration in the discourses of the official campaigns have legitimised a toxic (inter)national logic. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2019, 16, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, W. 1953. I Welcome Germany Back. In Churchill: The Power of Words; Gilbert, M., Ed.; Da Capo Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, R. A Tale of Two Referendums: 1975 and 2016. Political Q. 2016, 87, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. EU Referendum Results. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/politics/eu_referendum/results (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Cameron, D. Leader’s Speech. 2014. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=356 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Thatcher, M. Leader’s Speech. 1981. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=127 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Major, J. Leader’s Speech. 1996. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=142 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. Speech at Conservative Party Conference. 2020. Available online: https://www.ukpol.co.uk/boris-johnson-2020-speech-at-conservative-party-conference/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Churchill, W.A. Property-Owning Democracy. 1946. The Sunset Years 1945–63. In Winston Churchill’s Speeches; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2004; pp. 337–420. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, A. Leader’s Speech. 1956. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=106 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Thatcher, M. Leader’s Speech. 1990. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=136 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Islentyeva, A. The Undesirable Migrant in the British Press: Creating Bias through Language. Neuphilol. Mitt. 2018, 119, 419–442. [Google Scholar]

- Islentyeva, A. A Corpus-Based Analysis of Ideological Bias: Migration in the British Press; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. Discourse, Grammar and Ideology: Functional and Cognitive Perspectives; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P. Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis; Continuum: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black, J. Britain as a Container: Immigration Metaphors in the 2005 Election Campaign. Discourse Soc. 2006, 17, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. Metaphors of migration over time. Discourse Soc. 2021, 32, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambra, G.K. Brexit, the Commonwealth, and exclusionary citizenship. Open Democr. 2016, 8, 1945–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, H. ‘Leader’s Speech.’ 1961. Available online: http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=110 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Churchill, W. 1948. What will happen When They Get the Atomic Bomb? The Sunset Years 1945–63. In Winston Churchill’s Speeches; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2004; pp. 337–420. [Google Scholar]

- Islentyeva, A. The English Garden under Threat. Roses and Aliens in The Daily Telegraph Editorial; Work in Progress; Hawel, M., Ed.; VSA: Hamburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zappettini, F. Taking the left way out of Europe: Labour party’s strategic, ideological and ambivalent de/legitimation of Brexit. J. Lang. Politics 2022, 21. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Islentyeva, A. On the Front Line in the Fight against the Virus: Conceptual Framing and War Patterns in Political Discourse. Yearb. Ger. Cogn. Linguist. Assoc. 2020, 8, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, T. Book Review: Islentyeva, Anna. Corpus-based Analysis of ideological bias: Migration in the British press. London: Routledge. J. Corpora Discourse Stud. 2021, 4, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glencross, A. British Euroscepticism as British Exceptionalism: The Forty-Year “Neverendum” on the Relationship with Europe. Studia Dipl. 2014, 67, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).