1. Introduction

The impact of COVID-19 across the world has been pervasive, profound, and in many cases, long lasting. The full extent of the death toll, increased stress and isolation, economic loss, and numerous negative impacts can never be quantified. The global pandemic has even changed human interactions, with some of these changes likely persisting beyond the pandemic. Luckily, the impacts have not all been negative. The virus has also caused an “emergence by emergency” [

1]—wherein potentially disruptive and technologically aided improvements have been sped up. The rapid uptake and utilization of telehealth, including in medicine, as well as mental and behavioral health, serves as one example of a service whose time has come.

Utilization of telehealth has been expanding and the pandemic has resulted in an increased uptake [

2] among practitioners. Whether this expanded reliance on telehealth will continue remains to be seen. To this end, the current study examined the use of telehealth throughout rural Nebraska and examined practitioners’ perspectives on the utilization of telebehavioral health (TBH).

What follows is a brief summary of the telehealth literature, followed by a description of the current study’s methodology, results, and a discussion outlining how the findings provide new knowledge and understanding about the interplay of telehealth, COVID-19, and rural communities. The current study is not all-inclusive—it was necessarily delimited to focus on one state as a way to begin the examination of behavioral telehealth services during and following the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in rural communities. A small sample was necessary to ensure that data were captured during the pandemic.

1.1. Literature Review

Telehealth is a form of healthcare provided through the use of technology to connect individuals with a provider from a remote site. It covers a broad range of services including medical care, education services, follow-up care, patient monitoring, and behavioral health services. Telehealth has been utilized as a form of healthcare delivery for over 100 years [

3]. In the late 1800s, medical attention was given via phone and radio to avoid travel when unnecessary or not feasible, such as when providing care for individuals working overseas [

3]. The demand for telehealth continued to increase, eventually progressing to hospital-based telehealth. For example, Nebraska has had telebehavioral health services for several decades. A secure telehealth connection was created between the Nebraska Psychiatric Institution and Norfolk State Hospital during the mid-1900s [

3].

Although today’s versions of telehealth may look starkly different than practices in the 1950s, telehealth’s core benefit of not requiring two individuals to be in the same place at the same time is a driving factor for its adoption. Today’s technologies have improved telehealth practice so that it can more closely resemble face-to-face interactions. Telehealth in the current times capitalizes on new technologies and modalities of practice. Telehealth can be delivered synchronously or asynchronously depending on client preference as well as insurance regulations. The most common form of telehealth is in the synchronous form of live video, but other modalities include phone, email, text, patient portals, and applications that can be used on a smartphone or computer [

4].

Despite the advancements and improvements in these new technologies, the adoption of telehealth services, including various forms of behavioral services, has been limited. Some reasons for this include legal barriers and policies that make telehealth a challenge to adopt, client preferences, and concerns about insurance reimbursement [

5].

This brief overview of telehealth in behavioral health settings merely serves to set the stage for the interaction between COVID-19, rural communities, and telebehavioral health. For a more extensive review of the literature and the history of telehealth and telebehavioral health, consult the work of Gogia (2020) [

6] and Luxton et al. (2016) [

7].

1.2. COVID-19 and Telehealth

It would be hard to overstate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on society. Employment, education, family life, and all facets of life have been touched in one way or another. Behavioral health services were no exception. Due to local, state, and federal mandates and recommendations, business as usual was not an option. Clients and practitioners alike were forced to change routines to prevent further spreading of the virus. In-person contact and interaction was reduced as much as possible.

Given the importance of behavioral health services, merely postponing or eliminating such services was not an option. Thus, practitioners and agencies alike had to identify alternate means of serving clients. Telebehavioral health was one clear solution that offered opportunities for services while limiting physical contact. However, before providers could make a quick pivot to these new form of services, agencies had to await changes to local, state, and federal regulations as well as changes from insurance providers.

1.2.1. Regulation Adjustments

The push to avoid in-person meetings paired with the necessity of services appeared to cause enough pressure to lead to changes in state regulations as well as standard insurance practices. Numerous state regulations that previously made telehealth more challenging to adopt were relaxed for various forms of telehealth [

8], including behavioral health services. The federal government adjusted the regulations concerning the platforms providers may use to deliver telehealth services, an adjustment that will likely require additional long-term deliberation in order to maintain confidentiality [

9,

10]. In-state licensure requirements were waived or modified, and states had more discretion to determine how to address behavioral health needs during the pandemic [

11]. In the United States, interstate licensure requirements were also examined [

12]. In some cases, clinicians were able to switch already established clients to telehealth as well as seeing new clients via telehealth without the initial in-person meeting [

10].

Another regulation change or relaxation is centered around the “originating site” regulation. This regulation placed strict guidelines on what constituted a rural area to allow telehealth services to only be offered in the most remote locations. This rule was relaxed and, in some cases, completely removed. In addition, the stipulation that the client must receive telehealth services through a specified clinic nearby in order to avoid exposure to COVID-19 was relaxed [

13]. This specific regulation change grants easier access not only to those living in rural communities, but now also to individuals in urban areas. One study suggested three out of four patients with depression in urban areas have difficulties accessing mental or behavioral health services due to structural or psychological barriers [

14]. This could potentially be addressed with telehealth if the originating site regulation remains void.

Insurance companies modified rules related to reimbursement to ease the transition to telehealth services [

15]. As a result, TBH went from an occasional and acceptable option to a necessary and even preferred option for many agencies. Some insurance companies waived the restrictions limiting the use of telehealth and increased the reimbursement for telehealth services [

16].

1.2.2. Adjusting to Technology

The impact of COVID-19 did not stop with a mere transition to telebehavioral health services. As the threat of COVID-19 intensified, so did the effect of the virus on the public’s well-being. The pandemic has led to decreased mental well-being, increased risk of domestic violence, and increased substance abuse among populations across the globe [

17]. This has resulted in an increased demands for services, which places an even greater strain on providers and further highlights inadequacies in the mental and behavioral health system. Telehealth may serve as one tool to lighten the load on agencies and practitioners. Some recent research has already found that telehealth services can lead to high levels of client satisfaction and be utilized to address feelings of isolation and improve coping skills among telehealth clients [

18].

According to Pruitt et al. (2014), a large part of the hesitancy from clients to make the transition to telehealth services is due to the lack of technological knowledge. The COVID-19 crisis has led individuals who were already accessing behavioral health services to convert to telehealth. Those who were unexposed to the technological advances of telehealth learned how to navigate new platforms in order to continue receiving treatment. Since the somewhat “forced” change from in-person to virtual counseling, satisfaction rates from clients have remained high [

19]. Clients were not the only ones needing to experiment with new technologies. Practitioners also were tasked with practices in new technologically mediated ways. Just as the willingness and aptitude to make these adjustments varied by client, it also varied by the experience of service providers [

20].

1.3. Telehealth in Rural Settings

Even before the pandemic, rural communities faced challenges addressing the behavioral health needs of residents. Such challenges include, but are not limited to, a shortage of providers, transportation challenges, a lack of confidentiality in rural communities, language challenges, and technological challenges. Although there is a body of evidence validating these challenges, there is also an expanding body of research to suggest that telehealth can help to address several of these challenges.

1.3.1. Shortage of Providers

The lack of qualified behavioral health providers in rural communities, in addition to primary healthcare, is well documented (e.g., [

21]). This shortage is caused by numerous challenges, including a lack of opportunities to be trained in rural practice, a requirement in most cases to reside in urban areas for training, and the competition with more affluent urban areas to attract top talent. Should a client need to visit with a particular specialist, the lack of access is heightened even further [

22]. Despite efforts by states to address the shortage of qualified practitioners in rural communities, the shortage persists. Such efforts should not be abandoned. In the interim, while strategies to increase the number of rural behavioral health practitioners continue, telehealth may be a means of addressing severe shortages, particularly with specialists [

23].

1.3.2. Travel Challenges

Transportation can be a major challenge in rural communities as well, particularly for individuals who do not have access to their own vehicles. Many rural communities have little or no public transportation. Furthermore, individuals in rural communities may also face the problem of time commitment associated with travel to other communities where they can access more services. If an individual is employed during normal business hours, accessing services that are hundreds of miles away may not be feasible. Often, individuals who face these barriers will be unable to schedule appointments as regularly as needed or will delay care [

24]. Telehealth can yet again be used to address some of these challenges. By offering clients the option of fully utilizing telehealth services or a hybrid of telehealth and in-person services, clients can adhere to a more regular schedule of services. The time and monetary savings that telehealth may afford extends not only to the client, but also to many agencies and providers who travel to meet clients in their homes or in different rural communities [

25].

1.3.3. Confidentiality Challenges

Rural communities are notorious for being places where privacy is hard to maintain. Although close-knit communities can be beneficial in some ways, there may also be concerns around issues of confidentiality [

26], especially when it comes to accessing mental health services or substance abuse treatment support. Telehealth may help to address this issue by allowing individuals, in the privacy of their own home in some cases, to meet with clinicians who reside in other locations [

18]. This can both increase privacy and decrease any chance of complications caused by existing relationships between practitioners and clients. In short, telehealth can help to address concerns around privacy, or the stigma associated with seeking treatment, and thus lead to greater participation by rural residents [

25].

1.3.4. Language Challenges

As previously stated, rural residents may have little or no access to specialists and highly trained practitioners in their community. Further challenges are presented when an individual needs to meet with a clinician who speaks a language other than English. Although many rural communities are depicted as predominately white and/or unchanging in terms of demographics, the reality is that rural communities are often much more diverse than portrayed. In fact, there are rural communities across the United States where the demographics represent even more diversity, in terms of percentages, than the largest cities in the United States. Some projections are that in the United States there are more than 2000 rural communities where racial and ethnic minorities are the majority of the population [

27]. This can be particularly evident in rural communities where there are strong employment opportunities [

28]. These communities can become a place for numerous immigrants and minorities, including many non-native English speakers. Combining the rural nature of these communities with a need for services in languages other than English highlights a further challenge some individuals face in getting needed health and behavioral health services. Yet again, telehealth can help to address this need. Practitioners who are fluent in a potential client’s native language need not reside in the same community.

1.3.5. Technology Challenges

Although telehealth may address several of the barriers to health services in rural communities, the utilization of telehealth is dependent on suitable and reliable technology, such as high-speed internet or a quality phone signal. Without reliable connections, potential telehealth clients in rural communities face poor connection, resulting in low-quality video and audio, a lag, or possible disconnection [

29]. When issues such as these arise, they create an interruption in services. It is also important to note that rural areas, which tend to lack behavioral health access, also often lack sufficient internet services to fully benefit from telehealth services [

29], or in certain context may mean that there is literally no access to broadband internet [

30].

Adapting to technology may also be a barrier, especially for older adults in rural communities. Vaportzis et al. (2017) explained that older adults have more difficulties understanding the continuously developing technology than adolescents and young adults. Despite the frustration of adapting to new technology, older adults still express interest in learning whether the technology will improve their life satisfaction [

31].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Current Research

The current research emerges at the intersection of telebehavioral health, rural communities, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Through interviews with practitioners across the state of Nebraska, including multiple rural practitioners, researchers sought to answer the following questions:

How prevalent is the use of telehealth for behavioral and mental health services in the state of Nebraska?

How has COVID-19 influenced the utilization of telehealth?

How has telehealth impacted services for rural communities?

What are the impacts of telehealth services? This includes the impacts on clients as well as service provision and practices.

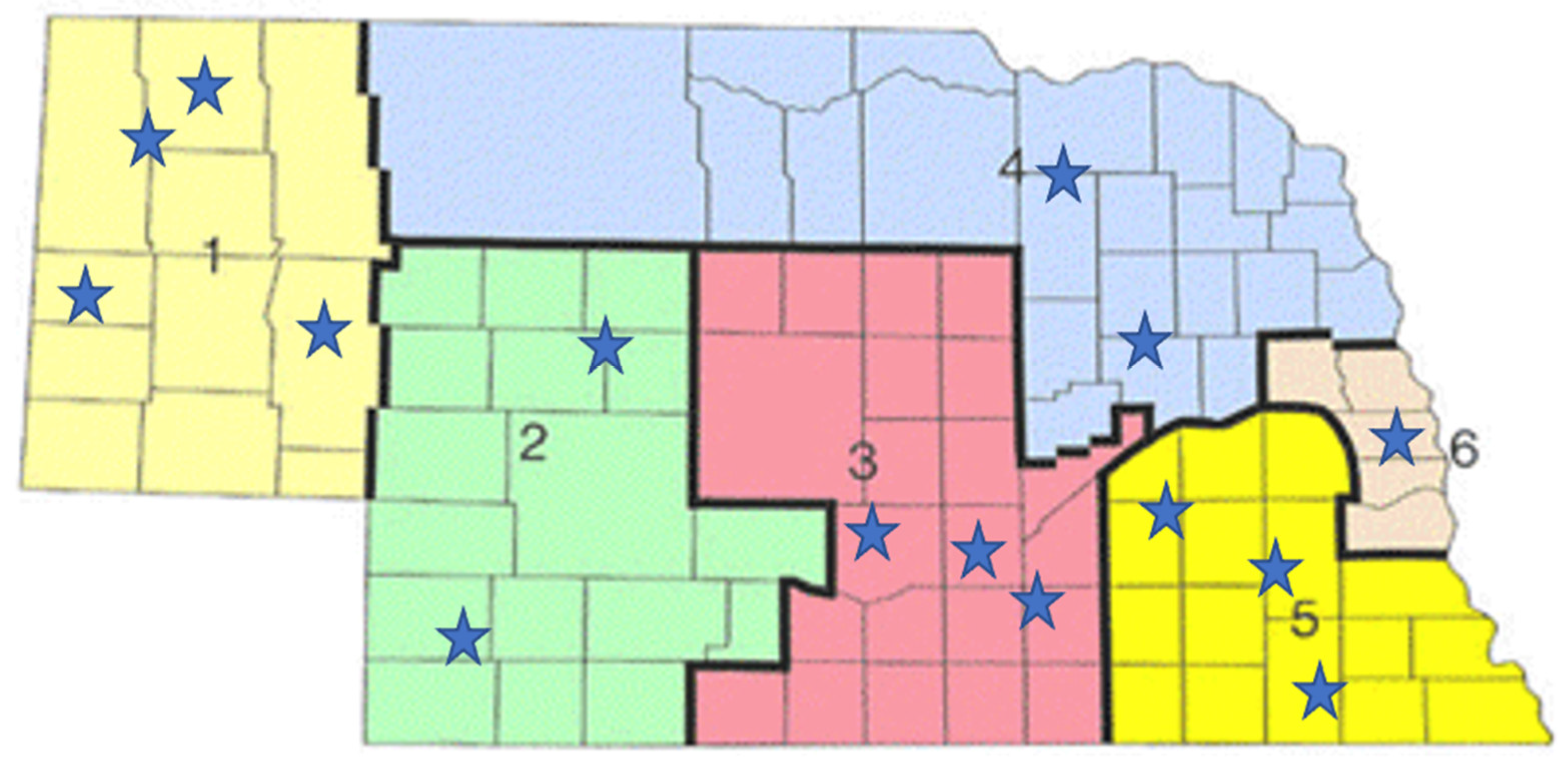

The research was conducted in two phases over a period of four months. In the first phase, researchers used the internet to identify behavioral health agencies across the state, ensuring multiple agencies from each of the state’s six regions (see

Figure 1). Once the database of 51 agencies was developed, researchers contacted all 51 agencies and asked about their utilization of telehealth services. The phase of the research was completed through short phone calls where office staff answered a short list of questions related to the use of telehealth at their agency.

2.2. Study Site and Sample

This research centers on behavioral health practice in Nebraska, particularly rural Nebraska. Research suggests that every county, apart from the Omaha metro area, has a shortage of practitioners [

32]. Although the state is seeking to address this shortage of providers through the commendable work of agencies such as the Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska (see,

https://www.unmc.edu/bhecn/, accessed on 1 September 2021), the shortage persists and clients in extremely rural communities may literally have to travel hours to access services.

Language is yet another challenge. Cities in Nebraska such as Lexington and Crete have seen a major demographic shift brought on in part because of employment offered by meatpacking plants. The influx of immigrants and refugees results in communities that have a high need for better access to services, including various forms of behavioral health, in their native language. This demographic shift results in even greater disparities in access to care from a professional who speaks the native language of service recipients.

Finally, Nebraska faces major broadband challenges. Among all 50 states, Nebraska ranks 48th in terms of broadband access [

33]. Despite the great benefits that telehealth can provide, it is limited to individuals who have access to both the hardware and internet connectivity.

The sample to address the first research question included 51 behavioral health agencies from across the state. To be considered as a behavioral health agency, services had to include services such as parenting coaching, risk assessment, mental health counseling, family counseling, trauma counseling, drug and alcohol counseling, child-parent psychotherapy, substance use evaluations, case management, medication management, and comparable outpatient services. Researchers developed the list of agencies through an internet search that included the identification of agencies in each of the state’s six behavioral health regions (see

Figure 1). This phase of the research was completed through short phone calls where office staff answered a short list of questions related to the use of telehealth at their agency.

After contacting all 51 agencies, researchers selected 15 agencies for the interviews (see

Figure 1). Although it would have been ideal to complete 51 interviews, limited time and financial resources resulted in a smaller sample size. Researchers ensured that the selection included at least two agencies from each of the regions, with the exception of region six, which is the most urban of all of the regions. Prior to completing the interviews, all respondents were provided with documentation outlining the potential risks of participation and that the project had been approved by the Univeristy Institutional Review Board. Respondents provided verbal consent to participate. No names were recorded in the data file to ensure anonymity. Researchers conducted phone or Zoom interviews with behavioral health practitioners from 15 agencies across the state, with a focus on rural communities. The interviews generally lasted between 10 and 20 min. Researchers asked all practitioners a standard set of questions and recorded the responses as outlined below.

2.3. Research Procedures and Questions

Prevelance of Telebehavioral Health

To assess the prevalence of telehealth services in Nebraska, researchers called and spoke with office staff at 51 agencies. Office staff at the agencies answered yes or no questions to determine whether the agency utilized telehealth services. In phase two, which featured interviews with behavioral health practitioners, researchers asked each of the questions outlined in the following section. Data were analyzed by computing basic descriptive statistics on the number of similar responses to each of the interview questions.

3. Results

This section summarizes results from the interviews. The tables following each question indicate how many of the 15 respondents gave a specific answer. In summary tables where numbers do not add up to 15, respondents may have given multiple answers, or a response that was unique may have been excluded from the table and then included in a brief statement following the question and associated table.

- 1.

How prevalent is the use of telehealth for behavioral and mental health services in the state of Nebraska?

It should be noted that among the initial sample of 51 agencies, all except one agency were offering telehealth services. This one agency provided primarily in-home services for children. The responses to each of the following questions are based on the 15 interviews with practitioners. The responses highlight a myriad of perspectives and experiences with telehealth.

Summary of Responses of Practitioners

Additional services mentioned by one clinician include parenting coaching, risk assessment, case management, medication management, and other outpatient services.

Additional comments about issues with phone or internet connection challenges included a comment that when the internet was lagging or unreliable, they would switch to a phone call or complete necessary communication via text message. For certain types of clients and circumstances, it was necessary to schedule some face-to-face interviews. On multiple occasions it was necessary to reschedule appointments and hope that the technology would work better at the next appointment.

Respondents described why telehealth has been effective in addressing issues of transportation for reasons that included a reduction in the high financial cost of gas, vehicles, public transportation, or other means of travel. Additionally, respondents outlined that not all communities even have public transportation or driving services such as LYFT, or that some clients may not have a license or have had it revoked. Additional comments outlined that home services through telehealth are more convenient for many, including the elderly. Furthermore, telehealth can allow for better services to children, as parents’ work is not as impacted by having to spend time and money traveling for appointments.

Additional responses by one clinician included that clients had increased difficulty adjusting in the middle of a major crisis. Another comment outlined that young adults seemed to adjust more easily. Yet another response was that some clients quit for a time but came back only consenting to do so with the expectation that they would be able to return to face-to-face services, with some clients expressing a desire to continue with telehealth even after the pandemic.

An additional comment may by one clinician was that one benefit was not having to wait around if a client did not show. Other respondents described benefits such as financial savings for the office, clients receiving more services as they can transition to telehealth if they cannot come for various other reasons, and the fact that telehealth is now a skill that clinicians have to offer that they did not prior to the pandemic. Other respondents saw the change to telehealth as an opportunity for personal growth, developing new skills and new opportunities to “be with” clients. Finally, one respondent described that telehealth ensured personal health and safety.

Additional responses by one clinician included that telehealth ensures that all practices are in compliance with regulations, that some school policies do act as barriers, and that state regulations were relaxed due to COVID-19. In relation to state regulations, one clinician notes that if all regulations went back to pre-COVID-19 regulations, the agency would stop offering telehealth services.

Six respondents stated that this question was not applicable to their situation.

Additional comments made by one clinician included parental concern about children not paying attention during sessions. Another comment was about clients not feeling as safe doing telehealth compared to being at the agency.

4. Discussion

The following discussion addresses each of the four key research questions. The paper then concludes with a description of implications from the findings and identification of the limitations of the project.

4.1. How Prevalent Is the Use of Telehealth for Behavioral and Mental Health Services in the State of Nebraska?

As the results indicate, telehealth is highly prevalent, and its use increased due to COVID-19. With all 50 out of 51 agencies replying that they now offer telehealth services and all interviewees reporting an increase in their use of telehealth services, it is clearly a modality used across Nebraska. Furthermore, interviews highlighted that practitioners plan to continue to use telehealth services even beyond the pandemic.

Several interviewees also mentioned the role of insurers and of state regulations. Although practitioners desire to continue offering telehealth services, barriers through insurers and tightened state regulations can hinder the expansion of telehealth. Such sentiment is warranted and in line with research that highlights the need for serious dialogue among politicians and insurance companies about the future of telehealth-related regulations [

9]. These findings are consistent across states, as evidenced by the fact that states even relaxed some inter-state behavioral health practice rules to maximize the reach of telehealth services [

34].

4.2. How Has COVID-19 Influenced the Utilization of Telehealth?

As stated, COVID-19 has been a driving force for the expansion of telehealth. In some ways, it has forced states and insurers to relax rules and has made telehealth a more viable option. One major shift that COVID-19 brought about, which likely would not have been brought about through personal choice, was the wholesale shift to telehealth for many agencies. Due to restrictions, even clients who did not prefer or desire to utilize telehealth now had to either access services via telehealth or lose all access to services. This “forced” choice had a deep impact on both clients and practitioners.

As practitioners commented, some clients who were initially hesitant discovered that they enjoyed it or that there were real benefits, such as time and monetary savings through telehealth. Practitioners who had to offer all or most of their services through telehealth commented on how well it worked for certain subsets of clients, but also on how telehealth was inadequate in other contexts and circumstances depending on the type of services or the client. The pandemic has caused agencies to reexamine the use of telehealth and how much telehealth they should offer, for which clients, and for which types of services.

4.3. How Has Telehealth Impacted Services for Rural Communities?

The overall sentiment from practitioners was that telebehavioral health has provided important opportunities to serve rural communities more effectively. The responses from practitioners paralleled existing research suggesting that telehealth can help to address challenges that rural communities face, such as reducing travel time and transportation challenges [

35], weather challenges, and issues of confidentiality. Additionally, telehealth can meet the needs of clients who require access to specialists or opportunities to connect with practitioners who speak their language. Despite such increased access, the reality must be acknowledged that individuals in rural communities, particularly racial and ethnic minority groups, may lack access to the technologies and internet connectivity necessary to reap the benefits of telehealth [

36]. It behooves governments and decision-makers to pursue opportunities to expand access to the internet and to reduce technological barriers, as such disparities in access further widen behavioral health inequities.

Despite these advantages and benefits of telehealth in rural communities, telehealth is not the best or only suitable option for all clients. Furthermore, more training for clinicians and access to reliable internet connections are necessary for clients and practitioners to reap the benefits of telehealth.

4.4. What Are the Impacts of Telehealth Services?

4.4.1. Benefits

Interview respondents identified various benefits of telehealth that may drive future expansion and commitment to telehealth. These benefits include that telehealth is an important tool to provide necessary services when circumstances do not permit other alternatives. Although COVID-19 was a driving factor moving clients towards telehealth, weather, travel, and other challenges can also create contexts where the alternative to telehealth means accessing no services. Telehealth also can save clinicians, and clients, time and money associated with travel and generally increase access. These findings are consistent with existing literature (e.g., [

37]). An additional benefit not specifically mentioned by practitioners, but one that they likely experienced, is that telehealth services can reduce exposure between clinicians and infected clients [

12].

In terms of actual clinical practice, overall results suggest that telehealth played a role in increasing adherence to treatment plans, improved attendance at scheduled sessions, and in some cases even increased the efficacy of medication managements. Multiple clinicians also mentioned that clients were more likely to disclose.

4.4.2. Challenges

Telehealth does not come without drawbacks. Interviewees discussed that although it may be better than no services, telehealth is not as effective for specific clients or specific types of clinical techniques and practices. Furthermore, telehealth can result in increased concerns about privacy and safety. Multiple respondents also clearly stated that even if telehealth is an effective option, it is not viable without the necessary internet speeds and access to technology. This lack of reliable internet is consistent with the access gaps already existing between rural and urban communities [

37]. Going forward, there are some concerns among practitioners about the expansion of telehealth. Legal and insurance restrictions or regulations may return to pre-COVID-19 status. Despite these challenges, the overall sentiment among practitioners is that they plan to utilize telehealth more, which seems to suggest that the benefits outweigh the challenges.

5. Conclusions

This research examined telebehavioral health, rural communities, and COVID-19. It should be noted that although telehealth in rural settings has received increased attention and focus and, in some cases, funding, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on telebehavioral health practice that is unparalleled. The pandemic forced agencies, practitioners, and clients to experiment with various technologies and approaches to telehealth. State regulations and insurance accommodations went quickly into place in a manner that political pressure could not have done. Although the tragedies associated with the pandemic cannot be overstated, this research adds to a growing body of findings that highlight that the impact of the pandemic on telebehavioral health is also expansive.

As the research highlights, telehealth is a promising practice and has many potential benefits. These benefits are not automatic. New research is needed to examine which types of telehealth practice are the most effective and for which clients in which contexts. As the research suggests, different treatment options and contexts call for unique approaches. Additional research on hybrid models of treatment that include some aspects of face-to-face treatment as well as telepractice should receive additional examination from researchers. Although the body of research is expanding, COVID-19 will likely be a pivot point in the opportunity to examine, experiment, and evaluate telehealth in ways that have never been done before. This article, along with many others, can serve to further validate and establish an evidence-based approach to telehealth practice.

Findings from this research should be considered in light of the limitations of the research design and associated challenges. While the 51 identified agencies represented various regions of the state, they do represent a convenience sample found online. Additionally, speaking with only 15 providers may not be representative of behavioral health providers. Furthermore, our Nebraska-specific focus may limit generalizability to other states and regions. Additionally, the United States-centric paradigm further limits generalizability, especially when countries across the world chose different approaches to address behavioral health needs during the pandemic [

38]. Despite these limitations, the research is additive because of the breadth of questions asked in the interviews and the timeliness of the research and the impact of COVID-19 on agencies, particularly in rural communities.

5.1. Broader Implications for Telehealth

The implications of the current research when combined with the growing body of research on telehealth in general can also help to inform regulators and insurers, agency leaders and practitioners, educators, and state and federal officials.

5.1.1. Regulators and Insurers

As the demand for mental health services continues to increase, clinicians remain hopeful that policy changes will become permanent once the pandemic has slowed. The policy changes enacted due to the pandemic have not only allowed existing clients to continue receiving services but have also opened access to new clients to begin receiving services through telehealth. Changes to the previous policy requiring an established relationship between the provider and client before transitioning to technology-based interventions have allowed clinicians to accept new clients with the intention of providing services via telehealth immediately [

13].

Individuals who were unable to access behavioral health services via telehealth prior to policy changes have been able to begin seeing a clinician due to the changes in the originating site policy. Service providers were encouraged by the changes in insurance regulations to expand services, also making it possible to reach more people who were unable to attend in-person appointments. Once insurance programs transitioned to payment parity, providers were reimbursed for the full cost, creating an incentive to provide more services in the form of telehealth [

9]. In addition, by continuing the provision of behavioral health services via telehealth, individuals in rural settings would be able to access services more easily and more often [

23]. Children and adolescents in schools would be more likely to overcome barriers to services they might face in their home, allowing attendance to be more consistent and increasing follow-through with treatment plans [

39].

Individuals across the United States have become reliant on the services they are receiving through telehealth, and to abruptly end access to services could have severe negative repercussions. Thus, regulation and insurance barriers must be examined and modified to best meet the needs of clients, particularly in rural communities. Although the current research was United States and Nebraska specific, the impact of regulations merits considerations across the globe. The reality that countries chose to utilize a myriad of measure and approaches to respond to the virus [

40] highlights a need for a country-by-country, or even state-by-state, analysis of legislation and regulations.

5.1.2. Agency Leaders and Practitioners

To more completely fulfill agency missions and commitments to serve clients, practitioners and agencies must continue to experiment with telehealth practice. Telehealth offers opportunities to serve new clients who in the past may not have accessed any needed services. Telehealth can open new modes of clinical practice, not only serving new clients but also offering new and needed supports to clients in numerous settings [

13]. As technology and internet-based services broaden, the different methods of delivering services broaden as well. According to Ramsey and Montgomery (2014) [

41], incorporating additional types of telehealth, including asynchronous services, would enhance the client’s experience. By doing so, clinicians would be able to meet a higher demand and provide to a broader clientele. Practitioners in behavioral health settings will benefit from reviewing recent research seeking to establish best practices. Rather than seeking to avoid tele-behavioral health, practitioners can appreciate the benefits and challenges associated with telebehavioral health and identify ways to maximize the benefits while minimizing the drawbacks.

5.1.3. Educators

The rapid expansion of telehealth has forced many practitioners into an arena of practice where they previously had little or no experience. As the body of research is established and best practices developed, it is important that educators preparing future behavioral health practitioners prepare students to practice in telehealth settings. Opportunities to complete internships and learn to use telehealth should be incorporated into all behavioral health educational programs. Such efforts not only prepare practitioners to be better service providers, but can also lead to better outcomes for clients. Additional training and educational opportunities should also be made available to current practitioners [

30].

5.1.4. State and Federal Leaders

As rural communities continue to face declining populations [

42] and numerous other challenges, telehealth can result in the provision of much-needed behavioral health services. However, such an option requires reliable telecommunications systems, including phone signals and broadband internet. The push for rural broadband has received ample attention and now has some funding in place [

43]—yet until the systems are in place, telehealth is still not possible in many rural communities. Additionally, as states and federal agencies seek to serve rural communities, programs to incentivize practitioners to move to and serve rural communities should be examined and compared to efforts to serve clients through telehealth. No single option will quickly “solve” rural access issues. Multiple options must be considered and compared to identify the best approaches for each context. These recommendations and implications extend not only to telebehavioral health but are also directly aligned with needs to address rural challenges in various domains.